Abstract

Context

Published reports to date have failed to demonstrate a decrease in abortion rates with increased dispersal of levonorgestrel emergency contraception (LNG EC).

Objective

To evaluate whether there is an association between statewide increases in LNG EC use and birth, fertility, and abortion rates.

Design

Ecological study. The number of LNG EC doses dispensed at all Planned Parenthood Association of Utah (PPAU) sites (n = 6) were obtained for 2000–2006. For this time period, birth and abortion data were obtained from the Utah Department of Health.

Setting

State of Utah.

Patients

Women of childbearing age.

Main Outcome Measures

Birth rates were calculated as the number of live births per 1000 population; general fertility rates, abortion rates, and LNG EC rates were calculated per 1000 women of childbearing age (15–44 years).

Results

Between 2000 and 2006, yearly distribution of LNG EC increased from 11,263 to 52,083 doses. Over this period, the rate of Plan B use per 1000 women age 15–44 years increased from 21.30 doses/1000 to 87.82 doses/1000, an increase of 312%. During the same period, there were corresponding changes in the statewide birth rate (−2.94%), general fertility rate (0.73%), and abortion rate (−6.36%). Pearson correlation coefficients were statistically significant for the association between the LNG EC rate and the birth rate (−0.9053; P = .0050) and the abortion rate (−0.8749; P < .001), but not between the Plan B rate and the general fertility rate (0.2446; P = .5970).

Conclusion

This ecological study represents, to the authors' knowledge, the first statistically significant association between increasing rates of LNG EC distribution and decreasing abortion rates.

Background and Introduction

Unintended pregnancy accounts for approximately half of all US pregnancies.[1] Emergency contraception is one way women who have unprotected intercourse can decrease their risk for unintended pregnancy. Several formulations of emergency contraception (EC) have been studied in large, well-conducted randomized trials.[2–4] All these trials support the use of emergency contraception to decrease the risk for pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. Low pregnancy rates (1% to 2%) in women participating in EC trials fueled optimistic predictions about the potential of EC to reduce abortion rates. A frequently cited model anticipated that US abortion rates would be cut in half with widespread use of EC.[5] However, a systematic review of increased access to EC was unable to document a reduction in community abortion rates.[6]

Soon after being introduced, the dedicated levonorgestrel (LNG) EC product (Plan B®; Duramed Pharmaceuticals) became the most popular method of EC in the United States. Planned Parenthood Association of Utah (PPAU) has observed a steady increase in distribution of LNG EC from 2000 to 2006. Over this time, the number of doses dispensed per year has increased from 11,263 to 52,083. This study used ecological data to assess whether there is a relationship between increased use of Plan B by women in Utah and birth, fertility, and abortion rates.

Methods

For each year from 2000 to 2006, rates for LNG EC use were calculated by dividing the number of doses of LNG EC dispensed by the 6 PPAU clinics by the yearly population of Utah women of reproductive age (15–44 years old). All rates are reported per 1000 women age 15–44 years. LNG EC doses dispensed are prospectively tallied by PPAU. This is accomplished by using practice management software system at PPAU. PPAU endorsed the study and fully cooperated with supplying the researchers with the necessary data. LNG EC was first available at PPAU in 2000 and has been offered to any woman desiring it since then. The vast majority of patients presenting for EC have recently had unprotected intercourse and take the medication immediately. Women may have the medication dispensed for future use but this is uncommon. A consultation is not required. Data were available on LNG EC distribution for 2000–2006; these data were broken down by age from 2003 to 2006. Data on the annual Utah population from 2000 through 2006 were obtained from the Utah Department of Health's Indicator-Based Information System for Public Health (IBIS-PH). This information is publicly available on their Website: http://ibis.health.utah.gov/

Birth[7] and abortion[8,9] data were obtained from the Utah Department of Health. Crude birth rates were calculated by dividing the number of live births to Utah residents by the Utah population, general fertility rates were calculated by dividing the number of live births to Utah residents by the population of women age 15–44 years, and abortion rates were calculated by dividing the number of abortions to Utah residents by the population of women age 15–44 years. Population estimates were obtained from IBIS-PHand used data from the Governor's Office of Planning and Budget. They are estimated as of July 1 of each year. Rates and percentage changes were calculated by age category for births, abortions, and Plan B use. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the association between trends in Plan B use and birth, fertility, and abortion rates, overall and by age. Linear regression was also used to estimate the change in the birth and abortion rates associated with LNG EC distribution on an ecological level.

The study protocol was submitted to the University of Utah Institutional Review Board (IRB). The Board determined that the study was exempt from IRB approval. The study was not considered human subjects research because only de-identified data were used, no patient charts were reviewed, and no patients were contacted. Data were analyzed using Stata 9.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

Results

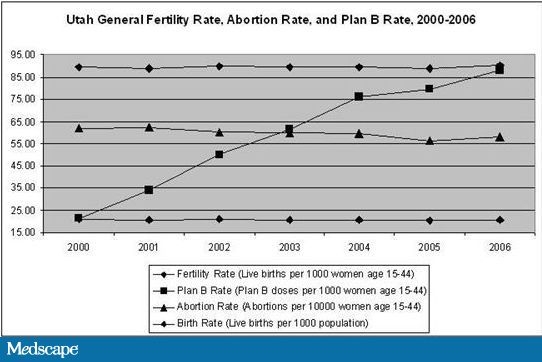

Between 2000 and 2006, PPAU increased its distribution of LNG EC from 11,263 to 52,083 doses. Over this period, the number of LNG EC doses dispensed increased 362% and the rate of Plan B use per 1000 women age 15–44 years increased from 21.30 doses per 1000 to 87.82 doses per 1000, an increase of 312%. During the same period, corresponding changes occurred in the statewide birth rate (−2.94%), general fertility rate (0.73%), and the abortion rate (−6.36%) (Table 1 and Table 2 and the Figure).

Table 1.

Utah Population, Live Births, Abortions, and Plan B Prescriptions Given, 1999–2006

| Year | Utah Population | Utah Female Residents, Age 15–44 Years | Number of Live Births to Utah Residents | Number of Abortions to Utah Residents | Number of Plan B Doses Given at Planned Parenthood Clinics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2,193,006 | 520,259 | 46,243 | 3160 | 0 |

| 2000 | 2,246,553 | 528,738 | 47,331 | 3279 | 11,263 |

| 2001 | 2,305,652 | 540,102 | 47,915 | 3372 | 18,288 |

| 2002 | 2,358,330 | 548,648 | 49,140 | 3300 | 27,517 |

| 2003 | 2,413,618 | 557,267 | 49,834 | 3338 | 34,433 |

| 2004 | 2,469,230 | 566,034 | 50,653 | 3379 | 43,047 |

| 2005 | 2,547,390 | 581,167 | 51,517 | 3279 | 46,317 |

| 2006 | 2,615,129 | 593,040 | 53,475 | 3444 | 52,083 |

Table 2.

Utah Birth Rate, Fertility Rate, Abortion Rate, and Plan B Rate, 1999–2006

| Year | Crude Birth Rate (Live Births Per 1000 Population) | General Fertility Rate(Live Births Per 1000 Women Age 15–44 Years) | Abortion Rate (Abortions Per 1000 Women Age 15–44 Years) | Plan B Rate (Doses Per 1000 Women Age 15–44 Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 21.09 | 88.88 | 6.07 | 0.00 |

| 2000 | 21.07 | 89.52 | 6.20 | 21.30 |

| 2001 | 20.78 | 88.71 | 6.24 | 33.86 |

| 2002 | 20.84 | 89.57 | 6.01 | 50.15 |

| 2003 | 20.65 | 89.43 | 5.99 | 61.79 |

| 2004 | 20.51 | 89.49 | 5.97 | 76.05 |

| 2005 | 20.22 | 88.64 | 5.64 | 79.70 |

| 2006 | 20.45 | 90.17 | 5.81 | 87.82 |

Figure.

Utah birth rate/1000, fertility rate/1000, abortion rate/10,000, and Plan B rate/1000, 1999–2006.

Across all years, the highest rates of LNG EC distribution were among women age 18–19 years; rates were also high among women age 15–17 and 20–24 years. However, the largest increases in LNG EC distribution occurred among women age 40–44, 30–34, and 25–29years, with increases between 2003 and 2006 of 89%, 81%, and 79%, respectively. The smallest increases in LNG EC distribution between 2003 and 2006 (11%) occurred among women age 15–17 years (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Utah Fertility, Abortion, and Plan B Rates per 1000, 2003–2006, by Age

| Year | Fertility Rate/1000 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–17 Years | 18–19 Years | 20–24 Years | 25–29 Years | 30–34 Years | 35–39 Years | 40–44 Years | 45–49 Years | |

| 2003 | 15.588 | 49.100 | 128.661 | 178.410 | 114.445 | 48.640 | 10.002 | 0.535 |

| 2004 | 14.340 | 48.080 | 123.055 | 184.729 | 113.014 | 51.256 | 9.844 | 0.539 |

| 2005 | 15.079 | 45.408 | 116.702 | 184.988 | 114.671 | 50.852 | 9.736 | 0.447 |

| 2006 | 15.950 | 49.808 | 115.823 | 188.157 | 117.954 | 50.272 | 9.744 | 0.515 |

| Abortion Rate/1000 | ||||||||

| 2003 | 2.897 | 7.329 | 9.135 | 8.127 | 5.861 | 3.938 | 1.211 | 0.082 |

| 2004 | 2.485 | 7.336 | 9.592 | 7.871 | 5.641 | 3.879 | 1.274 | 0.121 |

| 2005 | 2.680 | 7.006 | 8.196 | 7.954 | 5.068 | 4.108 | 1.149 | 0.039 |

| 2006 | 2.650 | 7.753 | 8.638 | 8.321 | 5.172 | 3.576 | 1.147 | 0.103 |

| Plan B Rate/1000 | ||||||||

| 2003 | 129.750 | 201.692 | 96.094 | 35.033 | 12.267 | 6.558 | 2.474 | 0.961 |

| 2004 | 141.567 | 254.378 | 123.960 | 44.558 | 15.670 | 8.044 | 3.875 | 1.078 |

| 2005 | 136.270 | 254.361 | 136.180 | 52.692 | 17.507 | 8.373 | 3.589 | 1.380 |

| 2006 | 143.972 | 269.540 | 152.262 | 62.785 | 22.161 | 9.416 | 4.667 | 1.276 |

Table 4.

Percentage Change in Utah Fertility, Abortion, and Plan B Rates, 2003–2006, by Age

| Age (years) | Fertility Rate/1000 (%) | Abortion Rate/1000 (%) | Plan B Rate/1000 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15–17 | 2.32 | −8.53 | 10.96 |

| 18–19 | 1.44 | 5.78 | 33.64 |

| 20–24 | −9.98 | −5.44 | 58.45 |

| 25–29 | 5.46 | 2.39 | 79.22 |

| 30–34 | 3.07 | −11.77 | 80.65 |

| 35–39 | 3.35 | −9.19 | 43.57%– |

| 40–44 | −2.58 | −5.29 | 88.63 |

| 45–49 | −3.70 | 25.19 | 32.79 |

| Total | 0.83 | −3.05 | 42.13 |

Between 2003 and 2006, the fertility rate changed by <5% for all age groups except women age 20–24 years (10% decline) and 25–29 years (5% increase). Abortion rates decreased in all age groups with the exception of women age 18–19 (6% increase), 25–29 (2% increase), and 45–49 (25% increase) years (Table 4).

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the correlation between the LNG EC rate and Utah births and abortions. Overall, between 2000 and 2006, Pearson correlation coefficients were statistically significant for the association between the LNG EC rate and the birth rate (−0.9053; P =.0050) and abortion rate (−0.8749; P < 0.001), but not between the LNG EC rate and the general fertility rate (0.2446; P = .5970) (data not shown). The absolute changes in birth rate, fertility rate, abortion rate, and LNG EC rate were −0.62, 0.65, −0.36, and 66.52 per 1000 women, respectively (data not shown). Linear regression revealed a decrease in the abortion rate between 2000 and 2006 of 0.0074/1000 women of childbearing age for every 1 unit increase in the rate of LNG EC distribution per 1000 women of childbearing age (95% confidence interval [CI], −0.0121 to −0.0027; P = .01) and a decrease of 0.0103 births/1000 population for every 1 unit increase in the rate of LNG EC distribution per 1000 women of childbearing age (95% CI, −0.0158 to −0.0047; P = .005). When examined by age for 2003–2006, no correlation coefficients were significant for LNG EC and fertility or LNG EC and abortion in any group except for Plan B and fertility in women age 20–24 years (−0.9675; P = .0325) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients and P Values for Utah Age-Specific Plan B Rates With Fertility and Abortion Rates, 2003–2006

| Plan B and Fertility | Plan B and Abortion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Correlation Coefficient for Plan B and Fertility | P Value | Correlation Coefficient for Plan B and Abortion | P Value |

| 15–17 | −0.1182, | .8818 | −0.8320 | .1680 |

| 18–19 | −0.1557 | .8443 | 0.2723 | .7277 |

| 20–24 | −0.9675 | .0325* | −0.5214 | .4789 |

| 25–29 | 0.9292 | .0607 | 0.4423 | .5577 |

| 30–34 | 0.7879 | .2121 | −0.8206 | .1794 |

| 35–39 | 0.6427 | .3573 | −0.5425 | .4575 |

| 40–44 | −0.8344 | .1656 | −0.2851 | .7149 |

| 45–49 | −0.8492 | .1508 | −0.5238 | .4762 |

P < .05

Discussion

This ecological study highlights the rapid increase in distribution of LNG EC by PPAU clinics and associated decreases in the Utah abortion rate and birth rate, but not general fertility rate, between 2000 and 2006. The decrease in the Utah average annual percent change in the abortion rate of −1.05% between 2000 and 2006 reflects the annual average percent change of −1.20% in the United States between 1993 and 2006 as reported by Sedgh.[10] While this study reports ecological data, which limits our ability to make conclusions about causal relationships, it has unique strengths. First, the study sample represents a large population of EC users. The 250,318 doses reported here are more than 18 times the 13,564 women included in the systematic review on increased EC access.[6] Second, the medication was dispensed by use of the same protocol in all locations over a 6-year period.

The number of doses of Plan B used is imprecise but is a good estimate because PPAU is by far the state's largest supplier of EC. These data were collected before EC was available in pharmacies without a prescription, and PPAU had a much lower price for EC than Utah pharmacies. This favored use of PPAU as a supplier. A review of statewide Medicaid prescriptions for EC revealed that Utah Medicaid filled 235 Plan B claims among 68,684 unique female patients age 18–45 years enrolled in Medicaid at any point during 2006.[11] This represents 0.45% of all doses distributed by PPAU for that year. In August 2006, the US Food and Drug Administration approved LNG EC for over-the-counter use by women 18 years and older. A prescription is still required for women under 18. After oral levonorgestrel became available without a prescription, PPAU dispensed 38,921 doses in 2007. Despite availability at numerous pharmacies throughout the state, PPAU remains the largest statewide resource for women seeking EC. Other formulations of EC may have been dispensed during the study period, and other medical providers may have distributed doses or prescriptions that are not captured in our data. However, these probably represent a miniscule portion of total EC use and would have a small effect on the total rate of EC use. Some of the doses of LNG EC may have been distributed to women who live outside of Utah, and this would not be addressed in the statewide pregnancy outcome rates we calculated. As a result, the EC use by Utah residents may be overestimated. There is no reason to suspect that the proportion of doses used by non-Utah residents compared with Utah residents would have changed over time. These data cannot distinguish what proportion of pregnant women actually took EC. It also does not reveal how many women used multiple doses or how soon after unprotected intercourse women took the medication.

Rates of contraception use and the efficacy of chosen methods are important determinants for the abortion rate.[12,13] Data regarding these factors for the population studied are not available but could have affected abortion rates. Although we are not able to adequately assess the influence of contraception on our results, it is known that over the study period, PPAU, the State's largest supplier of contraception, did not change the number of clients served for hormonal contraceptives, IUDs, or vasectomies.

One distinguishing factor of this study is that it is likely that all the EC doses distributed were consumed. For example, in Glasier and colleagues' 2004 study,[14] 17,800 women received advance provision of up to 5 doses of EC but only an estimated 8081 doses were used. Even though fewer doses were dispensed to women in Utah, the use rate is probably much greater because women sought out the medication and paid for it. This greatly increases the likelihood that the medication will be used immediately. It is possible that women purchased EC ahead of need for use, but that is unlikely.

Despite the enormous number of EC doses used in Utah from 2000 to 2006 and the statistically significant decrease in abortion and birth rates identified, our ecological study design does not allow us to conclude that these changes are due to increased LNG EC use. However, our findings demonstrate a decrease in abortion rates with increasing LNG EC use and contrast the negative findings of several other studies incorporating more robust designs. These differences may be due to the unique nature of reproductive outcomes in the Utah population, the general decrease in abortion rates seen nationwide in recent years, increased general use of contraceptives, or differences in study design. However, not reporting this information could lead to publication bias and a misperception of, at least, the potential value of EC in reducing unintended pregnancy and abortion.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: Trends in Levonorgestrel Emergency Contraception Use, Births, and Abortions: The Utah Experience See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Contributor Information

David K. Turok, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Utah, Utah Author's email address: david.turok@hsc.utah.edu.

Sara E. Simonsen, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine & Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Utah, Utah.

Nicole Marshall, Oregon Health Sciences University, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oregon.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1803–1810. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11767-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Lancet. 1998;352:428–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellertson C, Webb A, Blanchard K, et al. Modifying the Yuzpe regimen of emergency contraception: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1160–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trussell J, Stewart F, Guest F, Hatcher RA. Emergency contraceptive pills: a simple proposal to reduce unintended pregnancies. Fam Plan Perspect. 1992;24:269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raymond EG, Trussell J, Polis CB. Population effect of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:181–188. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250904.06923.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Indicator-Based Information System for Public Health (IBIS-PH) 2008. Available at: http://ibis.health.utah.gov/home/Welcome.html Accessed August 27, 2008.

- 8.Office of Vital Records and Statistics; Utah Department of Health. Abortions by county and zipcode, residents. Utah: 2006. 2001–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office of Vital Records and Statistics; Utah Department of Health; Utah's Vital Statistics Abortions. 2006. Technical Report No 259. 2008.

- 10.Sedgh G, Henshaw SK, Singh S, Bankole A, Drescher J. Legal abortion worldwide: incidence and recent trends. Int Fam Perspect. 2007;33:106–116. doi: 10.1363/3310607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Division of Healthcare Financing Data Warehouse. Salt Lake City. Utah: Utah Department of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bongaarts J, Westoff CF. The potential role of contraception in reducing abortion. Stud Fam Plann. 2000;31:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2000.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marston C, Cleland J. Relationships between contraception and abortion: a review of the evidence. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2003;29:6–13. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.006.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasier A, Fairhurst K, Wyke S, et al. Advanced provision of emergency contraception does not reduce abortion rates. Contraception. 2004;69:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]