Abstract

Estradiol, acting on a membrane-associated estrogen receptor-α (mERα), induces an increase in free cytoplasmic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) needed for progesterone synthesis in hypothalamic astrocytes. To determine whether rapid estradiol signaling involves an interaction of mERα with metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1a (mGluR1a), changes in [Ca2+]i were monitored with the calcium indicator, Fluo-4 AM, in primary cultures of female postpubertal hypothalamic astrocytes. 17β-Estradiol over a range of 1 nm to 100 nm induced a maximal increase in [Ca2+]i flux measured as a change in relative fluorescence [ΔF Ca2+ = 615 ± 36 to 641 ± 47 relative fluorescent units (RFU)], whereas 0.1 nm of estradiol stimulated a moderate [Ca2+]i increase (275 ± 16 RFU). The rapid estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux was blocked with 1 μm of the estrogen receptor antagonist ICI 182,780 (635 ± 24 vs. 102 ± 11 RFU, P < 0.001) and 20 nmof the mGluR1a antagonist LY 367385 (617 ± 35 vs. 133 ± 20 RFU, P < 0.001). Whereas the mGluR1a receptor agonist (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenyl-glycine (50 μm) also stimulated a robust [Ca2+]i flux (626 ± 23 RFU), combined treatment of estradiol (1 nm) plus (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenyl-glycine (50 μm) augmented the [Ca2+]i response (762 ± 17 RFU) compared with either compound alone (P < 0.001). Coimmunoprecipitation demonstrated a direct physical interaction between mERα and mGluR1a in the plasma membrane of hypothalamic astrocytes. These results indicate that mERα acts through mGluR1a, and mGluR1a activation facilitates the estradiol response, suggesting that neural activity can modify estradiol-induced membrane signaling in astrocytes.

For rapid 17β-estradiol-induced membrane signaling in hypothalamic astrocytes, mER-α must interact with mGluR1a resulting in a dramatic increase in free cytoplasmic calcium concentration within seconds.

Our understanding of astrocytes in regulating nervous system function has evolved from providing structural support to regulating metabolic events (1) and synaptic function in adjacent neurons (2,3). Astrocytes respond to numerous transmitters, peptides, and steroids (4,5,6,7). Among these modulators of astrocyte function is estradiol, which profoundly influences their morphology and function (8), sexual differentiation (9), and steroidogenesis (10,11). Astrocytes in turn regulate numerous hypothalamic processes including regulation of releasing factors (12,13,14,15,16) and synthesis of neurosteroids (16,17,18,19). We focused on understanding estradiol signaling through the plasma membrane in hypothalamic astrocytes (20).

Astrocytes express estrogen receptor (ER)-α and ERβ intracellularly and on the plasma membrane (4,21,22,23). Activation of the membrane-associated ER (mER) initiates a rapid free cytoplasmic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) flux via the phospholipase C (PLC)/inositol trisphosphate (IP3) pathway that releases intracellular stores of calcium in neurons and astrocytes (4,24). A consequence of the estradiol-induced increase in [Ca2+]i is the de novo synthesis of progesterone by postpubertal hypothalamic astrocytes (10,25). In addition to estradiol, progesterone stimulation of the hypothalamus is essential for estrogen-positive feedback, ultimately leading to the LH surge (25,26).

In neurons, rapid membrane-mediated estradiol action requires the activation of mGluRs (27,28). The metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR)-1a was shown to mediate estradiol signaling through PLC leading to the release of IP3 receptor sensitive Ca2+ stores. Although astrocytes are not electrically excitable cells, proximal estradiol signaling in astrocytes and neurons appears to be similar (i.e. rapid, membrane initiated actions that involve PLC activation). The present experiments were done to determine whether, as in neurons, rapid membrane-mediated estradiol action in astrocytes requires the mGluR1a to activate intracellular signaling pathways. Hypothalamic astrocytes were obtained from postpubertal female rats and cultured. Both ERα and mGluR1a were present in the membrane fraction and directly interact as demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation. Blocking the mGluR1a with a selective antagonist, LY 367385, prevented the rapid estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux in astrocytes. Conversely, activating the mGluR1a with its agonist, (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenyl-glycine (DHPG), enhanced the magnitude of the rapid estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux. These results indicate a direct interaction of mERα and mGluR1a in mediating the rapid mobilization of intracellular calcium in astrocytes.

Materials and Methods

Primary cell cultures

Primary hypothalamic astrocyte cultures were obtained from postpubertal (postnatal d 50) Long-Evans female rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA). All experimental procedures were approved by the Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee at the University of California at Los Angeles. Briefly, a hypothalamic block was dissected with the boundaries: rostral extent of the optic chiasm, rostral extent of the mammillary bodies, lateral edges of the tuber cinereum, and the top of the third ventricle. The hypothalamus was enzymatically digested with trypsin and mechanically dissociated with a fire-polished glass Pasteur pipette. Cultures were grown for 7–10 d in DMEM/F12 (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 1% penicillin (10,000 IU/ml)-streptomycin (10,000 μg/ml) solution (PS; Mediatech, Herridon, VA) at 37 C. Once grown to confluency, astrocyte cultures were purified from other glial cells using a technique (10,11) modified from McCarthy and de Vellis (29). Briefly, flasks were shaken at 200 rpm at 37 C on an orbital shaker for at least 24 h to eliminate oligodendrocytes. Culture media were replaced after every shaking sequence.

For Ca2+ imaging, the DMEM/F12 medium with 10% FBS and 1% PS was removed from the flasks, and the cells were washed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; Mediatech), dissociated with a 2.5% trypsin solution, and then resuspended in 5 ml DMEM/F12 medium with 10% FBS. Astrocytes were centrifuged for 3 min at 80 × g, the supernatant was removed, the pellet of cells resuspended, plated onto poly-D lysine (0.1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)-coated 15 mm glass coverslips in 12-well culture plates, and incubated for 48–72 h in vitro before Ca2+ imaging. Cultures were routinely checked for purity using immunocytochemistry for glial fibrillary acidic protein (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) with a Hoechst 3342 nuclear stain (Sigma-Aldrich). Cultures were determined to be greater than 95% pure astrocytes as previously reported (10,11).

Intracellular Ca2+ measurements

Astrocyte cultures were grown in DMEM/F12 medium with 10% FBS and 1% PS and then steroid starved for 18 h by incubating in DMEM/F12 medium with 5% charcoal-stripped FBS at 37 C before experimentation. Immediately before imaging, astrocytes were incubated at 37 C for 45 min with HBSS and a calcium indicator, Fluo-4 AM (4.5 μm; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR), that was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and methanol. The cells were then washed three times with HBSS to remove the excess Fluo-4 AM. Glass coverslips were mounted into a 50-mm RC-61T-01 chamber insert (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) fixed into a 60- × 15-mm cell culture dish (Corning, Corning, NY) and placed into a QE-2 quick exchange platform (Warner Instruments) secured by a Corning retaining ring (Warner Instruments) and imaged on a series 30 stage adapter (Warner Instruments) for the Axioplan2-LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Cells were perfused with HBSS using a gravity perfusion system through PE160 tubing with MP series perfusion manifolds (Warner Instruments). Gravity perfusion and vacuum suction were directed by perfusion and suction tube holders using minimagnetic clamps (Warner Instruments). Fluo-4 AM imaging was performed using an IR-Achroplan ×40/0.80 water immersion objective (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with 488 nm laser excitation, and emission was monitored through a low-pass filter with a cutoff at 505 nm. An increase in fluorescence exceeding the baseline in response to the delivered drug was consider a [Ca2+]i transient.

Drugs were delivered by gravity perfusion and used in the following concentrations: 0.1–100 nm of cyclodextrin-encapsulated 17β-estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich); 1 μm of ICI 182,780 (Tocris, Ellisville, MO); 20 nm of LY367385 (Tocris); 1 nm to 50 μm of DHPG (Tocris). Stock solutions and final working concentrations were prepared in HBSS. Controls were stimulated with HBSS only.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Two-week-old primary astrocyte cultures (5 million cells per sample) were washed three times with PBS. The cell suspensions were passed through a 25-gauge needle (∼60 times) in 50 mm of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) with 1% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM; Anatrace, Maumee, OH) and protease inhibitors (1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm EDTA, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml aprotinin, all from Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Samples were incubated for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged (600 × g for l0 min, 4 C). The supernatant was used for coimmunoprecipitation and the pellet was discarded. Membrane fractions were obtained with a Mem-PER membrane protein extraction kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) with 1% DDM to optimize the protein extraction.

Concentrations of membrane and lysate proteins were determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) (30). For immunoprecipitation, similar concentrations of membrane and lysate proteins (2.5 mg/ml; sample volume ∼500 μl) were used. Endogenous antibodies were removed by incubating (30 min, 4 C) with protein-G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (100 μl; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The samples were then centrifuged (850 × g for 5 min) and the supernatants were retained. Rabbit polyclonal antibody against mGluR1a (1:100; Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Lake Placid, NY) was added to the supernatants and placed on a rotating stirrer at 4 C for 1 h. The antibody-protein complex was adsorbed with 100 μl of protein-G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The solutions were rotated overnight at 4 C and then washed 10 times with 20 mm of sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) containing 0.2% DDM. The adsorbed proteins were eluted from the beads with 0.1 m of glycine (pH 3.0) and then 1 m of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) was used to adjust the solution to pH 7.5.

Samples were run on SDS-PAGE using a 10% polyacrylamide gradient (Ready Gels; Bio-Rad). Proteins were electrically transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (GE Healthcare) and probed with ERα (1:1000; Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Temecula, CA) for 1 h, followed by an 1.5-h incubation with a secondary donkey antirabbit IgG (H+L) antibody (1:5000; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit and ECL Hyperfilm (GE Healthcare). Exposures varied from 0.5 to 2 min. Nonimmune rabbit serum (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) was used as a negative control. The procedure was also repeated in the reverse direction.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± sem in relative fluorescent units (RFU). A double-stimulation paradigm was used, such that each astrocyte was its own control. The ΔF Ca2+ was calculated as the difference between baseline fluorescence and peak response to stimulation. Statistical comparisons were made using the paired Student’s t test when comparing paired means across two groups and one-way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test when comparing means across three or more groups. The ED50 assessment was made by fitting a four parameter logit (sigmoid) estradiol vs. ΔF Ca2+ dose-response curve using the log scale for estradiol concentration. Statistical calculations were carried out using JMP 7.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SigmaStat 3.5 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Differences at the P < 0.05 level were considered significant.

Results

Effect of estradiol on [Ca2+]i flux in astrocytes

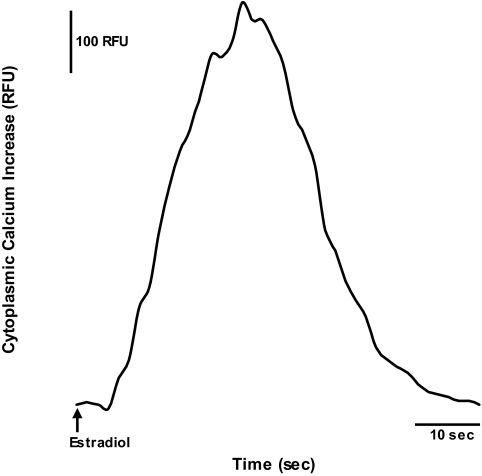

Approximately 75% of the hypothalamic astrocytes responded to 17β-estradiol at 1 nm and this robust [Ca2+]i flux began within 10 sec of treatment (Fig. 1). Using a double-stimulation paradigm, the astrocytes responded to repeated estradiol stimulation with an intervening 2-min washout period before the next treatment. The [Ca2+]i flux from both applications of estradiol at 1 nm were similar (ΔF Ca2+ = 615 ± 36 RFU for the first stimulation and ΔF Ca2+ = 663 ± 39 RFU for the second stimulation, n = 23, P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Representative real-time tracing of [Ca2+]i flux in response to 17β-estradiol stimulation in postpubertal hypothalamic astrocytes. Estradiol at 1 nm rapidly induced an increase in [Ca2+]i flux. The arrow indicates the time of estradiol stimulation.

Statistical analysis of mean [Ca2+]i flux between control and estradiol concentrations of 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 nm revealed significant differences (df = 4,98; F = 69.3; P < 0.001). Specifically, estradiol at 1, 10, and 100 nm induced a similarly robust [Ca2+]i flux (ΔF Ca2+ = 615 ± 36 RFU, n = 23; ΔF Ca2+ = 641 ± 47 RFU, n = 18; and ΔF Ca2+ = 629 ± 34 RFU, n = 16, respectively; Fig. 2). Although all of these responses were significantly greater than 0.1 nm of estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux (ΔF Ca2+ = 275 ± 16 RFU, n = 25, P < 0.001), the [Ca2+]i response induced with 0.1 nm of estradiol was significantly greater than the unstimulated control (ΔF Ca2+ = 102 ± 8 RFU, n = 21, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The 50% [Ca2+]i response (ED50) to estradiol was 0.15 ± 0.04 nm.

Figure 2.

Dose-response relationship between estradiol exposure and change in [Ca2+]i flux in postpubertal hypothalamic astrocytes. Astrocytes stimulated with estradiol at 0.1–100 nm all induced a statistically significant [Ca2+]i response. Estradiol at 1, 10, and 100 nm produced a robust [Ca2+]i flux (ΔF Ca2+ = 615 ± 36 RFU, n = 23; ΔF Ca2+ = 641 ± 47 RFU, n = 18; and ΔF Ca2+ = 629 ± 34 RFU, n = 16, respectively) that were all significantly greater than the response to estradiol at 0.1 nm (ΔF Ca2+ = 275 ± 16 RFU, n = 25, P < 0.001). The [Ca2+]i response for 0.1 nm of estradiol was significantly greater than control (ΔF Ca2+ = 102 ± 8 RFU, n = 21, P < 0.001). *, Significantly different (P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test).

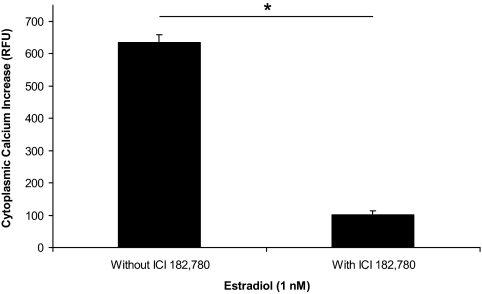

Estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux acts through an ER

We confirmed that the rapid estradiol action on [Ca2+]i flux is blocked with the ER antagonist, ICI 182,780 (4,10). For the antagonism studies, astrocytes were stimulated with estradiol and those astrocytes that responded with a [Ca2+]i flux (ΔF Ca2+ = 635 ± 24 RFU, n = 22; Fig. 3) were tested again with ICI 182,780 and estradiol. The initial 1 nm of estradiol stimulation was followed by a 2-min washout and then perfused with ICI 182,780 (1 μm) for 7 min before a second estradiol (1 nm) stimulation. The second estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux was significantly attenuated by ICI 182,780 (ΔF Ca2+ = 102 ± 11 RFU, n = 22, P < 0.001; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of ICI 182,780, an ER antagonist, on the change in [Ca2+]i flux on exposure to estradiol in postpubertal hypothalamic astrocytes. Estradiol at 1 nm stimulated a dramatic increase in [Ca2+]i flux (ΔF Ca2+ = 635 ± 24 RFU, n = 22, P < 0.001 vs. control). Pretreatment with 1 μm of ICI 182,780 for 7 min significantly blocked the estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i response (ΔF Ca2+ = 102 ± 11 RFU, n = 22, P < 0.001). *, Significantly different (P < 0.001, paired Student’s t test).

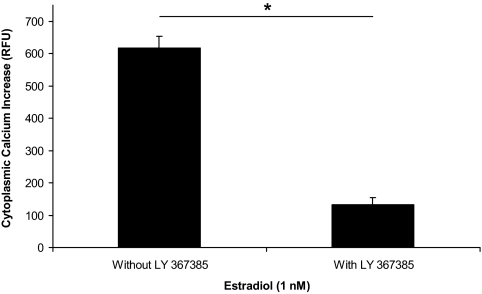

mGluR1a is required for estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux

A similar double stimulation protocol was used to study whether the estradiol-induced increase in [Ca2+]i flux was mGluR1a dependent. The initial 1 nm of estradiol stimulation (ΔF Ca2+ = 617 ± 35 RFU, n = 19; Fig. 4) was followed with a 2-min washout, and then the cells were perfused with the mGluR1a antagonist, LY 367385 (20 nm), for 7 min before restimulating with estradiol at 1 nm. The second estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux was significantly reduced compared with the first (ΔF Ca2+ = 133 ± 20 RFU, n = 19, P < 0.001; Fig. 4) due to antagonism of the mGluR1a.

Figure 4.

Effect of LY 367385, mGluR1a antagonist, on the change in [Ca2+]i flux on exposure to estradiol in postpubertal hypothalamic astrocytes. Calcium imaging of astrocytes stimulated with 1 nm of estradiol resulted in a [Ca2+]i response (ΔF Ca2+ = 617 ± 35 RFU, n = 19, P < 0.001 vs. control) that was significantly blocked with LY 367385 (ΔF Ca2+ = 133 ± 20 RFU, n = 19, P < 0.001). *, Significantly different (P < 0.001, paired Student’s t test).

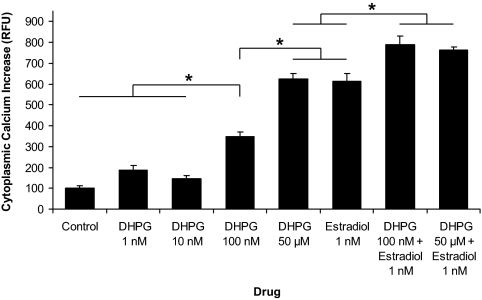

To determine whether activation of the mGluR1a would substitute for mERα activation by estradiol, astrocytes were treated with the mGluR1a agonist, DHPG. Statistical analysis of mean [Ca2+]i flux between control, DHPG (1 nm, 10 nm, 100 nm, and 50 μm), estradiol (1 nm), and estradiol (1 nm) in combination with DHPG (100 nm or 50 μm) revealed significant differences (df = 7,157; F = 119.9; P < 0.001). A high dose of DHPG (50 μm) induced a robust activation of [Ca2+]i flux (ΔF Ca2+ = 626 ± 23 RFU, n = 25) that was similar in magnitude to 1 nm of estradiol (ΔF Ca2+ = 615 ± 36 RFU, n = 23, P > 0.05; Fig. 5). The [Ca2+]i response to 50 μm of DHPG was significantly greater than that observed for 100 nm of DHPG (ΔF Ca2+ = 346 ± 25 RFU, n = 19, P < 0.001), which stimulated a higher [Ca2+]i flux than 10 nm of DHPG (ΔF Ca2+ = 146 ± 13 RFU, n = 17, P < 0.001), 1 nm of DHPG (ΔF Ca2+ = 188 ± 20 RFU, n = 17, P < 0.001), and the unstimulated control (ΔF Ca2+ = 102 ± 8 RFU, n = 21, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). Interestingly, estradiol (1 nm) in combination with DHPG (100 nm or 50 μm) produced a significantly greater [Ca2+]i flux (ΔF Ca2+ = 790 ± 42 RFU, n = 19 and ΔF Ca2+ = 762 ± 17 RFU, n = 24, respectively) compared with 1 nm of estradiol (P < 0.001), 100 nm of DHPG (P < 0.001), or 50 μm of DHPG (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). The [Ca2+]i flux stimulated by 1 nm of estradiol in combination with 100 nm of DHPG was statistically similar to the response with 1 nm of estradiol in combination with 50 μm of DHPG (P > 0.05; Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

DHPG, mGluR1a agonist, augmented the estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i response in postpubertal hypothalamic astrocytes. DHPG at 50 μm stimulated an estradiol-like activation of [Ca2+]i flux (ΔF Ca2+ = 626 ± 23 RFU, n = 25) compared with estradiol at 1 nm (ΔF Ca2+ = 615 ± 36 RFU, n = 23, P > 0.05). DHPG at 100 nm did not produce the same magnitude of response (ΔF Ca2+ = 346 ± 25 RFU, n = 19) as estradiol at 1 nm (P < 0.001) or DHPG at 50 μm (P < 0.001). However, DHPG at 100 nm induced a statistically greater [Ca2+]i flux compared with DHPG at 10 nm (ΔF Ca2+ = 146 ± 13 RFU, n = 17, P < 0.001), DHPG at 1 nm (ΔF Ca2+ = 188 ± 20 RFU, n = 17, P < 0.001), and the unstimulated control (ΔF Ca2+ = 102 ± 8 RFU, n = 21, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in [Ca2+]i flux between DHPG at 10 nm, DHPG at 1 nm, and the unstimulated control (P > 0.05). Astrocytes stimulated with estradiol at 1 nm in combination with either DHPG at 100 nm or DHPG at 50 μm responded with a significantly greater [Ca2+]i flux (ΔF Ca2+ = 790 ± 42 RFU, n = 19 and ΔF Ca2+ = 762 ± 17 RFU, n = 24, respectively) than with estradiol or DHPG alone (P < 0.001 vs. estradiol at 1 nm, P < 0.001 vs. DHPG at 100 nm, and P < 0.001 vs. DHPG at 50 μm). Estradiol at 1 nm in combination with DHPG at 100 nm induced a similar [Ca2+]i flux compared with estradiol at 1 nm in combination with DHPG at 50 μm (P > 0.05). *, Significantly different (P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test).

Protein-protein interaction of mERα and mGluR1a

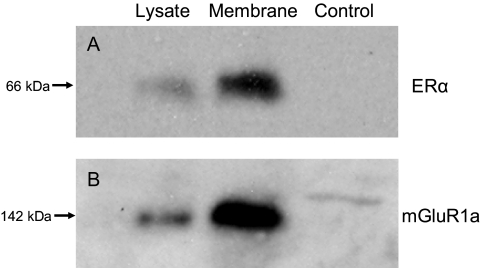

Coimmunoprecipitation was used to determine whether ERα could directly interact with mGluR1a in astrocyte membranes. Metabotropic GluR1a was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and membrane fractions, and the coprecipitated protein was detected with Western blots using rabbit polyclonal antibodies against ERα (Fig. 6A). To confirm the interaction, the order of the experiment was reversed: ERα was immunoprecipitated and the coprecipitated mGluR1a was identified with Western blotting (Fig. 6B). As expected, both mERα and mGluR1a were present in the plasma membrane. The apparent molecular masses determined for both receptors were similar to their full-length forms (i.e. the ERα band was at 66 kDa and the mGluR1a band was at 142 kDa).

Figure 6.

Coimmunoprecipitation of ERα and mGluR1a from cultured postpubertal hypothalamic astrocytes. The lanes are representative of coimmunoprecipitation experiments using cell lysate, the plasma membrane fraction, and nonimmune serum as a negative control, respectively. A, Antibodies against mGluR1a were used in the pull-down phase and the complex was detected with antibodies raised against ERα. B, The procedure was reversed, such that ERα antibodies were used to pull down the receptor complex, and antibodies against mGluR1a were used for detection.

Discussion

As in other cells of the nervous system, the effects of estradiol on astrocytes are complex and range from rapid, membrane-initiated signaling to slower intracellular ER-initiated transcriptional effects. Rapid actions of estradiol involve the activation of the PLC/IP3 pathway leading to the release of IP3 receptor-sensitive stores of intracellular Ca2+ from the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (4,24). Estradiol consistently and reproducibly produced an elevation of [Ca2+]i in hypothalamic astrocytes as demonstrated with the double-stimulation paradigm. Furthermore, subnanomolar doses of estradiol were sufficient to elevate [Ca2+]i flux in postpubertal hypothalamic astrocytes (Fig. 2). An ED50 of 0.15 nm indicates that the mER responds to physiological levels of estradiol that are reached during the proestrus surge (31,32,33).

There is growing support for the existence of membrane-associated estrogen-responsive receptors responsible for estradiol’s rapid action. However, controversy remains and many candidate ERs have been reported. The most widely held view is that both nuclear and plasma mERs are the products of the same genes and transcripts that produce ERα and ERβ (34). In our study, estradiol actions were blocked by the ER antagonist, ICI 182,780, suggesting that estradiol acts through an ER with pharmacology similar to the classic nuclear ERs to produce the [Ca2+]i response (Fig. 3). Previous studies demonstrated that these [Ca2+]i transients result from the activation of an ER directly associated with the plasma membrane, as suggested by the localization of ERs in the membrane fraction and the ability of the membrane impermeable 1,3,5(10)-estratrien-3,17α-diol-6-one-BSA construct to produce a similar response to estradiol (4,10). Although both ERα and ERβ have been reported in astrocyte membranes (4,22), the estradiol effects appear to be mediated through ERα based on published results (22) and preliminary data with the selective ERα agonist, propylpyrazole triole, and the selective ERβ agonist, diarylpropionitrile. Stimulation with propylpyrazole triole induced a rapid [Ca2+]i flux; however, diarylpropionitrile did not.

Alternative mERs that communicate rapid estrogen effects have been reported. One possibility is that estradiol directly activates an intracellular G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), named GPR30 (35,36,37). However, GPR30 is not located at the plasma membrane; rather it has been localized to the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus (37). Therefore, GPR30 cannot explain the estradiol-like response with the membrane impermeable 1,3,5(10)-estratrien-3,17α-diol-6-one-BSA construct (4,10). A membrane-associated binding protein that is Gαq coupled and activated by estrogen as well as the diphenylacrylamide estrogen agonist, syntaxin, resulting in the activation of PLC, has also been suggested (38). Further experiments with double-ERα/ERβ knockouts (ERα−/−/ERβ−/−) would be needed to confirm or refute the action of a Gαq-coupled membrane-associated binding protein. Lastly, the novel estrogen receptor, ER-X, that is neither ERα nor ERβ and is uninhibited by ICI 182,780 has been reported (39). Although ER-X can be activated by 17β-estradiol, it is unique in that it is preferentially activated by 17α-estradiol (40). The present results were not consistent with an ER-X-mediated action because ICI 182,780 inhibited the 17β-estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux. In addition, we have previously reported that astrocyte [Ca2+]i response is stereospecific as evidenced by the lack of effect with 17α-estradiol (4).

Although mERα behaves like a GPCR, there is little evidence that it binds and directly activates G proteins. In neurons, estradiol activates G protein signaling pathways with resulting rapid action on [Ca2+]i flux (41). However, neuronal mERs do not interact directly with G proteins; rather estradiol bound mERs activate mGluRs, which then serve as the intermediate to activate G proteins (27,28). The present experiments were done to determine whether mERα-mGluR1a interaction similarly mediates the rapid estradiol actions in hypothalamic astrocytes. Whereas the presence of glutamate receptors on astrocytes has been controversial (42), other studies identified mGluRs in hippocampal astrocytes in which they are necessary for the generation of spontaneous [Ca2+]i transients (43,44). In hypothalamic astrocytes, estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux was blocked by LY 367385, a mGluR1a antagonist (Fig. 4), suggesting that a mERα-mGluR1a interaction is needed to initiate rapid intracellular signaling. Moreover, coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated the presence of both full-length ERα and mGluR1a in the plasma membrane as well as the capacity of mERα and mGluR1a to directly interact with each other (Fig. 6).

In primary astrocyte cultures, the mGluR1a agonist, DHPG, demonstrates a dose-response relationship with its maximum response reached at 50 μm (45,46). Activation of the mGluR1a alone without estradiol induced a [Ca2+]i flux in hypothalamic astrocytes, although a high dose of DHPG (100 nm to 50 μm) was required (Fig. 5). The maximum estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i response was similar in magnitude to the maximum [Ca2+]i flux induced by DHPG (Figs. 2 and 5). This result was consistent with our experiments in vivo in which high doses of DHPG mimicked the rapid actions of estradiol on μ-opioid receptor internalization in hypothalamic neurons and sexual receptivity, events in which rapid estradiol actions require the mGluR1a (28). Although DHPG is more potent, with a lower EC50 than glutamate, which is the natural ligand for the mGluR1a in vivo, the maximal response to both drugs are similar (46,47).

Interestingly, estradiol in combination with DHPG stimulated a greater [Ca2+]i flux than the maximal response of estradiol or DHPG alone (Figs. 2 and 5). Furthermore, 100 nm of DHPG in combination with 1 nm of estradiol induced a similar [Ca2+]i flux compared with 50 μm of DHPG in combination with 1 nm of estradiol, which suggests that estradiol not only increases the maximal response of mGluR1a activation by DHPG but also lowers the threshold concentration of DHPG required to obtain a maximal response. These results suggest that optimal signaling through the mGluR1a may require an estradiol bound to mERα. One possible explanation is that the mGluR1a is in a conformation that does not allow optimal activation of intracellular signaling pathways. Only when estradiol bound mERα interacts with the mGluR1a does this receptor become fully activated. This could account for the additive effects of DHPG during estradiol stimulation (Fig. 5) and the inhibition of estradiol signaling with LY 367385 (Fig. 4). Alternatively, astrocytes may have a population of mGluR1a receptors that are preferentially activated by estradiol-stimulated ERα. Thus, regardless of how strongly the mGluR1a are activated by DHPG, the addition of estradiol will augment the response. Indeed, regardless of whether 100 nm or 50 μm of DHPG were used, 1 nm of estradiol augmented the response to the same absolute level (Fig. 5). In hippocampal neurons in vitro, DHPG did not replicate the estradiol action (27). It is unclear why this discrepancy exists between hippocampal neurons and hypothalamic neurons and astrocytes. Further experiments are needed to address this question.

These experiments examined the proximal signaling of mERα. Previously we demonstrated that activation of PLC produces IP3 that is necessary for the release of intracellular calcium stores via the IP3 receptor (4). In astrocytes, this [Ca2+]i flux stimulates the synthesis of neuroprogesterone (10). An increase in hypothalamic neuroprogesterone is obligatory for the initiation of the pituitary LH surge (25,26). Specifically, astrocyte-secreted neuroprogesterone activates estradiol-induced progesterone receptors in hypothalamic neurons resulting in the release of GnRH, the pituitary LH surge, and subsequent ovulation, the critical event in female reproduction (20). The present data help explain how mERα, acting through the mGluR1a, activates intracellular pathways involved in the synthesis of neuroprogesterone critical for the LH surge and ovulation. Further experiments are needed to define whether in astrocytes, like neurons, mERα-mGluR1a interactions also stimulate diacylglycerol, protein kinase C (PKC), MAPK and ultimately lead to the phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein (27). Estradiol activation of both protein kinase A (PKA) and PKC has been demonstrated in vivo and correlated with the regulation of sexual receptivity (48). Rapid estradiol activation of these protein kinases in astrocytes suggests another pathway through which estradiol acts to affect circuits regulating reproduction. Although estradiol-induced activation of PKA and/or PKC has not yet been demonstrated in astrocytes, the cAMP-driven phosphorylation of the steroid acute regulatory protein has been recently reported (49). Although certainly not the only protein involved (50,51,52), steroid acute regulatory protein expression and activation, the rate-limiting step in steroid biosynthesis, requires both PKA and PKC (53).

Intracellular calcium regulation and homeostasis is crucial for the control of gene expression, development, and survival in astrocytes (54). These experiments provide a mechanism to understand how estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux is modified in astrocytes, which may ultimately influence brain function. In astrocytes, elevated [Ca2+]i flux has been associated with modulation of microvascular tone and neuronal transmission (55,56,57,58,59,60,61). Furthermore, the [Ca2+]i response can be propagated between astrocytes as a [Ca2+]i wave to modulate neuronal activity over long distances (62). Such studies along with the present results suggest interactions between neurotransmission and circulating estradiol levels modulate central nervous system responses to sensory information and influence learning and memory. To establish such connections, further experiments will need to explicitly test these possibilities; however, changes in sensory processing with fluctuating estradiol levels during the estrous cycle have already been shown to underlie sexual receptivity (63). Many of estradiol’s actions undoubtedly influence hypothalamic astrocytes directly, but the present results showing a synergism between glutamate released after neuronal excitation and estradiol-induction of astrocytic [Ca2+]i flux suggest that these effects are more complex than originally envisioned.

The present results demonstrate that mERα interaction with mGluR1a is required to initiate the rapid cell signaling associated with the regulation of neuroprogesterone synthesis in hypothalamic astrocytes. Both receptor proteins were localized to the plasma membrane and demonstrated a direct protein-protein interaction. DHPG alone and estradiol alone are not as effective at stimulating [Ca2+]i flux as they are together, indicating that for maximal signaling in astrocytes, both glutamate and estradiol need to be present. These results suggest that estradiol may act most effectively on astrocytes that are near active glutamatergic nerve terminals.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the helpful comments and assistance of Dr. Victor Chaban (Charles R. Drew Health Sciences University, Los Angeles, CA).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD42635 and HD001281.

Disclosure Statement: J.K., O.R.H., J.O., and P.M. have nothing to declare.

First Published Online October 23, 2008

Abbreviations: [Ca2+]i, Free cytoplasmic calcium concentration; DDM, n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside; DHPG, (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenyl-glycine; ER, estrogen receptor; FBS, fetal bovine serum; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; HBSS, Hanks’ balanced salt solution; IP3, inositol trisphosphate; mERα, membrane-associated ER-α; mGluR1a, metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1a; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PLC, phospholipase C; PS, penicillin-streptomycin; RFU, relative fluorescent unit.

References

- Magistretti PJ 2006 Neuron-glia metabolic coupling and plasticity. J Exp Biol 209:2304–2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida H, Okabe S 2007 Direct astrocytic contacts regulate local maturation of dendritic spines. J Neurosci 27:331–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea G, Araque A 2007 Astrocytes potentiate transmitter release at single hippocampal synapses. Science 317:1083–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaban VV, Lakhter AJ, Micevych P 2004 A membrane estrogen receptor mediates intracellular calcium release in astrocytes. Endocrinology 145:3788–3795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst WD, Price GW, Rattray M, Wilkin GP 1998 Serotonin transporters in adult rat brain astrocytes revealed by [3H]5-HT uptake into glial plasmalemmal vesicles. Neurochem Int 33:11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosli E, Hosli L 1992 Autoradiographic localization of binding sites for arginine vasopressin and atrial natriuretic peptide on astrocytes and neurons of cultured rat central nervous system. Neuroscience 51:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka M, Wada M, Wu Q, Yamamoto A, Fujita T 2006 Functional expression of metabotropic GABAB receptors in primary cultures of astrocytes from rat cerebral cortex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 341:874–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mong JA, Blutstein T 2006 Estradiol modulation of astrocytic form and function: implications for hormonal control of synaptic communication. Neuroscience 138:967–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Amateau SK, Mong JA 2002 Steroid modulation of astrocytes in the neonatal brain: implications for adult reproductive function. Biol Reprod 67:691–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micevych PE, Chaban V, Ogi J, Dewing P, Lu JK, Sinchak K 2007 Estradiol stimulates progesterone synthesis in hypothalamic astrocyte cultures. Endocrinology 148:782–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinchak K, Mills RH, Tao L, LaPolt P, Lu JK, Micevych P 2003 Estrogen induces de novo progesterone synthesis in astrocytes. Dev Neurosci 25:343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashion AB, Smith MJ, Wise PM 2003 The morphometry of astrocytes in the rostral preoptic area exhibits a diurnal rhythm on proestrus: relationship to the luteinizing hormone surge and effects of age. Endocrinology 144:274–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavarretta I, Magnaghi V, Ferraboschi P, Martini L, Melcangi RC 1999 Interactions between type 1 astrocytes and LHRH-secreting neurons (GT1-1 cells): modification of steroid metabolism and possible role of TGFβ1. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 71:41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbiati M, Martini L, Melcangi RC 2002 Oestrogens, via transforming growth factor α, modulate basic fibroblast growth factor synthesis in hypothalamic astrocytes: in vitro observations. J Neuroendocrinol 14:829–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahesh VB, Dhandapani KM, Brann DW 2006 Role of astrocytes in reproduction and neuroprotection. Mol Cell Endocrinol 246:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwain IH, Arroyo A, Amato P, Yen SS 2002 A role for hypothalamic astrocytes in dehydroepiandrosterone and estradiol regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) release by GnRH neurons. Neuroendocrinology 75:375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akwa Y, Sananes N, Gouezou M, Robel P, Baulieu EE, Le Goascogne C 1993 Astrocytes and neurosteroids: metabolism of pregnenolone and dehydroepiandrosterone. Regulation by cell density. J Cell Biol 121:135–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung-Testas I, Do Thi A, Koenig H, Desarnaud F, Shazand K, Schumacher M, Baulieu EE 1999 Progesterone as a neurosteroid: synthesis and actions in rat glial cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 69:97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwain IH, Yen SS 1999 Neurosteroidogenesis in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and neurons of cerebral cortex of rat brain. Endocrinology 140:3843–3852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micevych P, Soma KK, Sinchak K 2008 Neuroprogesterone: key to estrogen positive feedback? Brain Res Rev 57:470–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Segura LM, Naftolin F, Hutchison JB, Azcoitia I, Chowen JA 1999 Role of astroglia in estrogen regulation of synaptic plasticity and brain repair. J Neurobiol 40:574–584 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak J, Karolczak M, Krust A, Chambon P, Beyer C 2005 Estrogen receptor-α is associated with the plasma membrane of astrocytes and coupled to the MAP/Src-kinase pathway. Glia 50:270–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada A, Romeo HE, Micevych P 2007 Distribution and localization patterns of estrogen receptor-β and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors in neurons and glial cells of the female rat substantia nigra: localization of ERβ and IGF-1R in substantia nigra. J Comp Neurol 503:198–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer C, Raab H 1998 Nongenomic effects of oestrogen: embryonic mouse midbrain neurones respond with a rapid release of calcium from intracellular stores. Eur J Neurosci 10:255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micevych P, Sinchak K, Mills RH, Tao L, LaPolt P, Lu JK 2003 The luteinizing hormone surge is preceded by an estrogen-induced increase of hypothalamic progesterone in ovariectomized and adrenalectomized rats. Neuroendocrinology 78:29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell PE, Levine JE 2000 Stimulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone surges by estrogen. I. Role of hypothalamic progesterone receptors. Endocrinology 141:1477–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware MI, Weick JP, Becklund BR, Kuo SP, Groth RD, Mermelstein PG 2005 Estradiol activates group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling, leading to opposing influences on cAMP response element-binding protein. J Neurosci 25:5066–5078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewing P, Boulware MI, Sinchak K, Christensen A, Mermelstein PG, Micevych P 2007 Membrane estrogen receptor-α interactions with metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a modulate female sexual receptivity in rats. J Neurosci 27:9294–9300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy KD, de Vellis J 1980 Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J Cell Biol 85:890–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM 1976 A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher RL, Collins WE, Fugo NW 1974 Plasma concentration of LH, FSH, prolactin, progesterone and estradiol-17β throughout the 4-day estrous cycle of the rat. Endocrinology 94:1704–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins RA, Freedman B, Marshall A, Killen E 1975 Oestradiol-17β and prolactin levels in rat peripheral plasma. Br J Cancer 32:179–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh AA, Shaikh SA 1975 Adrenal and ovarian steroid secretion in the rat estrous cycle temporally related to gonadotropins and steroid levels found in peripheral plasma. Endocrinology 96:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razandi M, Pedram A, Greene GL, Levin ER 1999 Cell membrane and nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs) originate from a single transcript: studies of ERα and ERβ expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Endocrinol 13:307–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, Frackelton Jr AR 2000 Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol Endocrinol 14:1649–1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J 2005 Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 146:624–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER 2005 A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science 307:1625–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Bosch MA, Tobias SC, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ 2003 Rapid signaling of estrogen in hypothalamic neurons involves a novel G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor that activates protein kinase C. J Neurosci 23:9529–9540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand CD 2000 Novel sites and mechanisms of oestrogen action in the brain. Novartis Found Symp 230:56–69; discussion 69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand CD, Guan X, MacLusky NJ, Horvath TL, Diano S, Singh M, Connolly Jr ES, Nethrapalli IS, Tinnikov AA 2002 ER-X: a novel, plasma membrane-associated, putative estrogen receptor that is regulated during development and after ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci 22:8391–8401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micevych PE, Mermelstein PG 2008 Membrane estrogen receptors acting through metabotropic glutamate receptors: an emerging mechanism of estrogen action in brain. Mol Neurobiol 38:66–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel JM, Schipke CG, Ohlemeyer C, Theodosis DT, Kettenmann H 2003 GABAA receptor-expressing astrocytes in the supraoptic nucleus lack glutamate uptake and receptor currents. Glia 44:102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton MK, McCarthy KD 1999 Mature hippocampal astrocytes exhibit functional metabotropic and ionotropic glutamate receptors in situ. Glia 26:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zur Nieden R, Deitmer JW 2006 The role of metabotropic glutamate receptors for the generation of calcium oscillations in rat hippocampal astrocytes in situ. Cereb Cortex 16:676–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyderman H, Angehagen M, Sandberg M, Bjorklund U, Olsson T, Hansson E, Nilsson M 2001 α1-Adrenergic modulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor-induced calcium oscillations and glutamate release in astrocytes. J Biol Chem 276:46504–46514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servitja JM, Masgrau R, Sarri E, Picatoste F 1999 Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors mediate phospholipase D stimulation in rat cultured astrocytes. J Neurochem 72:1441–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ, Pin JP 1997 Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 37:205–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kow LM, Pfaff DW 2004 The membrane actions of estrogens can potentiate their lordosis behavior-facilitating genomic actions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:12354–12357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karri S, Dertien JS, Stocco DM, Syapin PJ 2007 Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression and pregnenolone synthesis in rat astrocyte cultures. J Neuroendocrinol 19:860–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung-Testas I, Hu ZY, Baulieu EE, Robel P 1989 Neurosteroids: biosynthesis of pregnenolone and progesterone in primary cultures of rat glial cells. Endocrinology 125:2083–2091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos V, Guarneri P, Kreuger KE, Guidotti A, Costa E 1992 Pregnenolone biosynthesis in C6–2B glioma cell mitochondria: regulation by a mitochondrial diazepam binding inhibitor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:5113–5117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JK 1994 Immunoreactivity for diazepam binding inhibitor in Gomori-positive astrocytes. Regul Pept 50:159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Jo Y, Stocco DM 2007 Regulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2: role of protein kinase A and protein kinase C signaling. J Endocrinol 193:53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberdi E, Sanchez-Gomez MV, Matute C 2005 Calcium and glial cell death. Cell Calcium 38:417–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Sanzgiri RP, Parpura V, Haydon PG 1998 Calcium elevation in astrocytes causes an NMDA receptor-dependent increase in the frequency of miniature synaptic currents in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 18:6822–6829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin T, Carmignoto G 2004 Neurone-to-astrocyte signalling in the brain represents a distinct multifunctional unit. J Physiol 559:3–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan SJ, MacVicar BA 2004 Calcium transients in astrocyte endfeet cause cerebrovascular constrictions. Nature 431:195–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasti L, Volterra A, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G 1997 Intracellular calcium oscillations in astrocytes: a highly plastic, bidirectional form of communication between neurons and astrocytes in situ. J Neurosci 17:7817–7830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano T, Tian GF, Peng W, Lou N, Libionka W, Han X, Nedergaard M 2006 Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci 9:260–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winship IR, Plaa N, Murphy TH 2007 Rapid astrocyte calcium signals correlate with neuronal activity and onset of the hemodynamic response in vivo. J Neurosci 27:6268–6272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonta M, Angulo MC, Gobbo S, Rosengarten B, Hossmann KA, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G 2003 Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat Neurosci 6:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR 2004 Glial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 36:1861–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff DW, Schwartz-Giblin S, McCarthy MM, Kow LM 1994 Cellular and molecular mechanisms of female reproductive behaviors. In: Knobil E, Neill JD, eds. The physiology of reproduction. 2nd ed. New York: Raven Press; 107–220 [Google Scholar]