Abstract

Objective To describe on a national basis ethnic differences in severe maternal morbidity in the United Kingdom.

Design National cohort study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS).

Setting All hospitals with consultant led maternity units in the UK.

Participants 686 women with severe maternal morbidity between February 2005 and February 2006.

Main outcome measures Rates, risk ratios, and odds ratios of severe maternal morbidity in different ethnic groups.

Results 686 cases of severe maternal morbidity were reported in an estimated 775 186 maternities, representing an estimated incidence of 89 (95% confidence interval 82 to 95) cases per 100 000 maternities. 74% of women were white, and 26% were non-white. The estimated risk of severe maternal morbidity in white women was 80 cases per 100 000 maternities, and that in non-white women was 126 cases per 100 000 (risk difference 46 (27 to 66) cases per 100 000; risk ratio 1.58, 95% confidence interval 1.33 to 1.87). Black African women (risk difference 108 (18 to 197) cases per 100 000 maternities; risk ratio 2.35, 1.45 to 3.81) and black Caribbean women (risk difference 116 (59 to 172) cases per 100 000 maternities; risk ratio 2.45, 1.81 to 3.31) had the highest risk compared with white women. The risk in non-white women remained high after adjustment for differences in age, socioeconomic and smoking status, body mass index, and parity (odds ratio 1.50, 1.15 to 1.96).

Conclusions Severe maternal morbidity is significantly more common among non-white women than among white women in the UK, particularly in black African and Caribbean ethnic groups. This pattern is very similar to reported ethnic differences in maternal death rates. These differences may be due to the presence of pre-existing maternal medical factors or to factors related to care during pregnancy, labour, and birth; they are unlikely to be due to differences in age, socioeconomic or smoking status, body mass index, or parity. This highlights to clinicians and policy makers the importance of tailored maternity services and improved access to care for women from ethnic minorities. National information on the ethnicity of women giving birth in the UK is needed to enable ongoing accurate study of these inequalities.

Introduction

Recent reports from the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health have highlighted inequalities in rates of maternal death among different ethnic minority groups.1 A greater than fivefold difference in rates exists between the group with the lowest rate of death (white) and that with the highest (black African). Similar differences in maternal death rates in ethnic minority groups have been observed in other countries with well developed healthcare systems,2 3 4 and substandard care has been found to contribute to the differences.5 However, in developed countries, the absolute numbers of maternal deaths are small, even in the most numerous ethnic groups. Study of severe maternal morbidity or “near miss” events complements the study of maternal deaths in many ways and can provide additional information that may guide interventions and prevention.6 7 8 Severe maternal morbidities occur more frequently than maternal deaths, and studies including such events may have greater power to investigate differences between women of different ethnicity. Studies of severe maternal morbidity may also allow for more rapid reporting and hence earlier identification of potential deficiencies in maternity care.9

The establishment of the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) has enabled the routine study of severe maternal morbidity on a national population basis for the first time in the United Kingdom.10 The primary aim of the study reported here was to use information from UKOSS to investigate whether differences exist in the incidence of specific severe maternal morbidities between women from different ethnic groups in the UK as well as in the incidence of maternal death. In addition, we sought to investigate on a national basis the role of differences in demographic and pregnancy related risk factors between ethnic groups in the occurrence of severe maternal morbidity.

Methods

We identified cases of severe maternal morbidity and comparison women through the monthly UKOSS mailing between February 2005 and February 2006.10 We asked clinicians to report any woman diagnosed with acute fatty liver of pregnancy, amniotic fluid embolism, antenatal pulmonary embolism, eclampsia, or peripartum hysterectomy.

The UKOSS methodology has been described in detail elsewhere.10 In brief, we sent UKOSS case notification cards every month to nominated reporting clinicians in each hospital in the UK with a consultant led maternity unit, with a tick box list to indicate whether they had seen any women, including women who died, with the conditions under study. We also asked them to return cards indicating a “nil report,” so that we could monitor rates of return of cards and confirm the denominator maternity population to calculate the incidence. In the UK, women may also deliver in midwifery led units or at home (in total approximately 3-6% of births); however, any women in one of these settings with a severe maternal morbidity, such as one of the included conditions, will always be transferred to a consultant led unit. Inclusion of all consultant led units thus allowed the study to cover the entire cohort of UK births with respect to the conditions under study.

When a clinician returned a card indicating a case we then sent a condition specific data collection form asking for details to confirm that the woman met the appropriate case definition. We asked clinicians reporting cases of peripartum hysterectomy, eclampsia, or antenatal pulmonary embolism to complete data collection forms for two comparison women, identified as the two women delivering immediately before the case in the same hospital. As part of the data collection, we asked them to indicate all women’s self reported ethnicity according to the classification used for the UK national census,11 as well as the occupation of the woman or her partner if she was not in paid employment. All data collected were anonymous. We assessed cases against pre-defined case definitions (box) to objectively confirm the diagnoses.

Definitions of severe maternal morbidities

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

Either acute fatty liver of pregnancy has been confirmed by biopsy or postmortem examination

Or a clinician has made a diagnosis of acute fatty liver of pregnancy with signs and symptoms consistent with acute fatty liver of pregnancy present

Amniotic fluid embolism

Either a clinical diagnosis of amniotic fluid embolism (acute hypotension or cardiac arrest, acute hypoxia, or coagulopathy in the absence of any other potential explanation for the symptoms and signs observed)

Or a pathological diagnosis (presence of fetal squames or hair in the lungs)

Antenatal pulmonary embolism

Either pulmonary embolism is confirmed antenatally with suitable imaging (angiography, computed tomography, echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging, or ventilation-perfusion scan showing a high probability of pulmonary embolism)

Or pulmonary embolism is confirmed antenatally at surgery or post-mortem examination

Or a clinician has made a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism antenatally with signs and symptoms consistent with pulmonary embolism present, and the patient has received a course of anticoagulation treatment of more than one week’s duration

Eclampsia

-

The occurrence of convulsions during pregnancy or in the first 10 days postpartum, together with at least two of the following features within 24 hours after the convulsions:

Hypertension (a booking diastolic pressure of <90 mm Hg, a maximum diastolic of ≥90 mm Hg, and a diastolic increment of ≥25 mm Hg)

Proteinuria (at least protein present in a random urine sample or ≥0.3 g in a 24 hour collection)

Thrombocytopenia (platelet count of less than 100×109/l)

An increased plasma alanine aminotransferase concentration (≥42 IU/l)

Or an increased plasma aspartate aminotransferase concentration (≥42 IU/l).

Peripartum hysterectomy

Any woman giving birth to an infant and having a hysterectomy during the same clinical episode

Additional case ascertainment

To ensure that all cases were identified, we independently contacted all radiology departments, liver units, and intensive care units and asked them to report any cases of the conditions under study, reporting only the year of birth and date of diagnosis. Where a case was identified that seemed not to have been reported through UKOSS, we contacted the relevant UKOSS reporting clinician and asked him or her to complete a data collection form. In addition, we contacted researchers from the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health at the end of the study and asked them to identify any maternal deaths from the conditions under study that occurred during the study period, again providing only the year of birth and date of diagnosis. We compared these with the cases of severe maternal morbidity leading to maternal death reported through UKOSS.

Statistical analyses

We used Stata version 9 software for all analyses. We used the χ2 test to compare categorical data and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare continuous data.

We calculated risks, risk differences, and risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals by using denominator data from the most recently available hospital episode statistics and birth registration data (2005) as a proxy for February to December 2005 and January to February 200612 13; we estimated the total number of maternities (women delivering) during the study period from the birth data to be 775 186. UK national data on the ethnic group of women giving birth are not available; only the mother’s country of birth is recorded. However, these data have been recorded in England since 1995 as part of the maternity hospital episode statistics.13 We adopted the method used in the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths to estimate the UK denominator births in each ethnic group.1 Data on women’s ethnic group came from maternity hospital episode statistics. We added to the white ethnic group women whose ethnic group was unknown, as this has been shown to produce an ethnicity distribution comparable to that of infants in England in the national census.14 We then adjusted the figures for England to estimate UK figures by multiplying by a factor calculated by dividing the total number of maternities in the UK by the number of maternities in England alone. We report rates of severe morbidity separately for all discrete ethnic groups comprising more than 1% of the total population.

We classified socioeconomic status according to the Office for National Statistics socioeconomic classification,15 on the basis of the woman’s occupation, unless she was not in paid employment, in which case we used the occupation of her partner.

We investigated the potential factors underlying ethnic differences in severe maternal morbidities by using a logistic regression analysis. We took this approach using information from comparison women, as national data do not have sufficient information on potential confounders. We developed a full regression model by including both explanatory and potential confounding factors in a core model if a hypothesis or evidence existed to suggest that they were causally related to severe maternal morbidity—for example, parity and maternal body mass index. We tested continuous variables for departure from linearity by the addition of quadratic terms to the model and subsequent likelihood ratio testing. We calculated odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. This analysis has 80% power at the 5% level to detect an odds ratio of ethnicity of 1.4 or greater.

Results

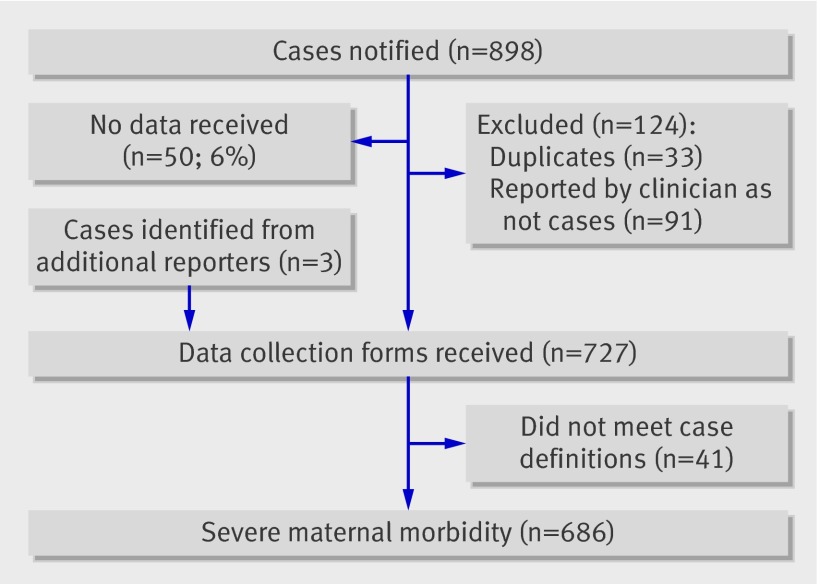

We identified 686 women with one of the five severe maternal morbidities in an estimated 775 186 maternities, representing a rate of 89 (95% confidence interval 82 to 95) cases per 100 000 maternities (fig 1). Table 1 shows the characteristics of women with severe morbidity. Seventy four per cent of women were white, and 26% were non-white. The estimated risk of severe maternal morbidity in non-white women was one and a half times that in white women (table 2). The risk was high in all non-white ethnic groups, although this was not statistically significant in some of the smaller groups. Black Caribbean women were the most highly represented ethnic minority group; in both black Caribbean and black African groups the estimated risk of severe maternal morbidity was more than double that in white women. Pakistani women also had a significantly higher morbidity rate (risk ratio 1.49, 95% confidence interval 1.06 to 2.09).

Fig 1 Case reporting for severe maternal morbidity and completeness of data collection

Table 1.

Characteristics of women with severe maternal morbidity

| Ethnic group | No (%) women | Median (range) age (years) | No (%) primiparous | No (%) managerial occupation | Median (range) body mass index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 505 (74) | 31 (15-55) |

204 (40) | 129/455 (28) | 24.7 (17.0-46.4) (n=439) |

| Indian | 18 (3) | 31.5 (23-41) | 11 (61) | 10 (56)* | 23.8 (18.1-33.3) (n=16) |

| Pakistani | 36 (5) | 33.5 (20-45) | 10 (28) | 8/28 (29) | 25.3 (17.3-36.5) (n=32) |

| Bangladeshi | 14 (2) | 34 (20-43) | 3 (21) | 1/12 (8) | 27.8 (17.7-35.1) (n=10) |

| Black African | 17 (2) | 33 (15-43) | 11 (65)* | 6 (35) | 26.4 (21.3-41.5) (n=13) |

| Black Caribbean | 46 (7) | 32.5 (18-45) | 18 (39) | 9/40 (23) | 27.2 (16.6-46.3)* (n=42) |

| Other | 50 (7) | 32.5 (15-49) | 23/49 (47) | 11/43 (26) | 22.9 (17.5-43.1)* (n=40) |

| Total | 686 | 31 (15-55) | 280/685 (41) | 174/613 (28) | 24.7 (16.6-46.4) (n=592) |

*P<0.05 compared with white ethnic group.

Table 2.

Numbers and estimated rates and relative risks of severe maternal morbidity in different ethnic groups. Values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals

| Ethnic group | No of women with severe morbidity | Estimated No of maternities | Morbidity risk per 100 000 maternities | Risk difference per 100 000 maternities | Risk ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 505 | 631 699 | 80 (73 to 87) | Reference | 1.0 (reference) |

| Indian | 18 | 20 253 | 89 (53 to 140) | 9 (−32 to 50) | 1.11 (0.69 to 1.73) |

| Pakistani | 36 | 30 215 | 119 (83 to 165) | 39 (0.3 to 79) | 1.49 (1.06 to 2.09) |

| Bangladeshi | 14 | 11 145 | 126 (69 to 211) | 46 (−20 to 112) | 1.57 (0.92 to 2.67) |

| Black African | 17 | 9 047 | 188 (110 to 301) | 108 (18 to 197) | 2.35 (1.45 to 3.81) |

| Black Caribbean | 46 | 23 527 | 196 (143 to 261) | 116 (59 to 172) | 2.45 (1.81 to 3.31) |

| Other | 50 | 49 298 | 101 (75 to 133) | 21 (−7 to 50) | 1.27 (0.95 to 1.70) |

| Any non-white | 181 | 143 485 | 126 (108 to 146) | 46 (27 to 66) | 1.58 (1.33 to 1.87) |

| Total | 686 | 775 184 | 89 (82 to 95) | NA | NA |

NA=not applicable

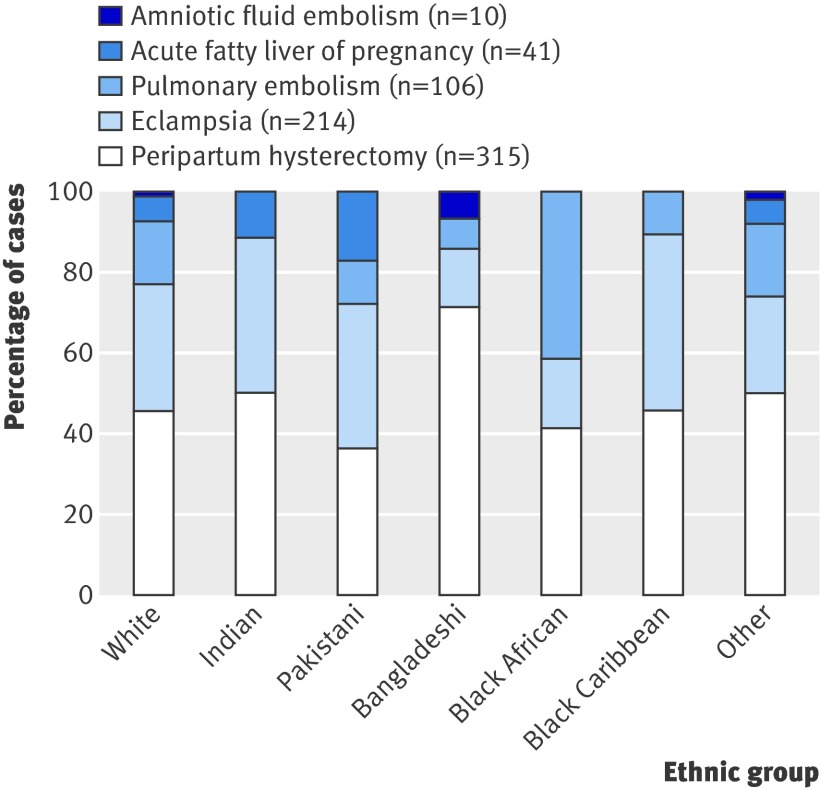

The most common severe morbidity was peripartum hysterectomy (46% of cases). We found no significant differences in the distribution of different morbidities between ethnic groups (fig 2).

Fig 2 Contribution of different conditions to severe maternal morbidity among different ethnic groups

In order to investigate further potential demographic and pregnancy related factors that might be responsible for the observed increase in severe maternal morbidities among women from ethnic minorities, we did a logistic regression analysis (table 3). Because of the small numbers of women in individual ethnic groups, we restricted our analysis to a comparison of white and non-white groups in order to have sufficient study power to identify any potential associations. Both maternal age and socioeconomic status were independently associated with the occurrence of severe maternal morbidities. However, the association between non-white ethnicity and increased risk of severe maternal morbidities remained significant even after adjustment for these factors together with maternal smoking status, body mass index, and parity.

Table 3.

Risk factors for severe maternal morbidity

| Risk factor | No (%) of cases (n=686) | No (%) of comparison women (n=1227) | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||

| Ethnicity: | ||||

| White | 505 (74) | 1007 (82) | 1† | 1† |

| Non-white | 181 (26) | 220 (18) | 1.64 (1.31 to 2.05) | 1.50 (1.15 to 1.96) |

| Age (years): | ||||

| <20 | 58 (8) | 62 (5) | 2.06 (1.41 to 3.00) | 2.62 (1.68 to 4.09) |

| 20-34 | 407 (59) | 897 (73) | 1† | 1† |

| ≥35 | 221 (32) | 264 (22) | 1.84 (1.49 to 2.28) | 1.77 (1.37 to 2.28) |

| Socioeconomic group: | ||||

| Managerial and professional occupations | 174 (28) | 334 (30) | 1† | 1† |

| Other occupations | 439 (72) | 766 (70) | 1.10 (0.88 to 1.37) | 1.32 (1.02 to 1.69) |

| Smoking status: | ||||

| Never/ex-smoker | 530 (79) | 893 (75) | 1† | 1† |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 138 (21) | 305 (25) | 0.76 (0.61 to 0.96) | 0.84 (0.64 to 1.10) |

| Booking body mass index: | ||||

| <30 | 468 (79) | 886 (83) | 1† | 1† |

| ≥30 | 124 (21) | 186 (17) | 1.26 (0.98 to 1.63) | 1.13 (0.87 to 6.45) |

| Pregnancy related factors | ||||

| Primiparous | 280 (41) | 525 (43) | 0.92 (0.76 to 1.11) | 1.07 (0.85 to 1.34) |

| Multiparous | 405 (59) | 696 (57) | 1† | 1† |

Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit χ2=6.56, df=8, P=0.585.

*Each adjusted for all other factors listed in the table.

†Baseline comparison group.

Discussion

We have identified clear differences in the risk of severe maternal morbidities between different ethnic groups on a national basis in the UK. Severe maternal morbidities occurred more than one and a half times more often among non-white women than in white women, more than twice as often among women of black African or black Caribbean ethnicity, and one and a half times more commonly in Pakistani women. The rate of severe maternal morbidities was higher in all other ethnic groups than in white women, although this difference was not statistically significant in any other individual ethnic groups. The increase in risk of severe maternal morbidities in non-white women seems to be independent of differences in age, socioeconomic and smoking status, body mass index, and parity between ethnic groups.

Comparison with other studies

No similar national studies have been done in the UK, and only one other prospective national study has used similar methods. A retrospective review of severe maternal morbidities that used the US National Hospital Discharge Survey between 1991 and 2003 noted a near doubling in the rate of morbidity in black women compared with white women.16 A similar retrospective database analysis in seven provinces of Canada covering deliveries occurring between 1991 and 2000 did not comment on risk ratios associated with ethnicity.17 The LEMMoN prospective study of severe maternal morbidity in the Netherlands, which had the specific aim of exploring potential ethnic differences, estimated a risk ratio of severe maternal morbidity of 1.3 between indigenous women and immigrant women.18 This study was developed in response to inequalities in maternal mortality in the Netherlands, with associated substandard care,5 and used similar methods to ours. The published study does not attempt to investigate potential factors underlying the increased risk in immigrant women.

We have shown that prospective collection of nuanced clinical information about severe maternal morbidity is possible on a national basis in a country with over 700 000 births annually and that this contributes additional information to the study of maternal deaths allowing further study of ethnic inequalities. The results are generalisable to countries with low rates of maternal death, high resource settings, and large ethnic minority populations. The pattern of risk of severe maternal morbidities we saw is similar to the differences observed between ethnic groups in rates of maternal death between 2003 and 2005.1 Black African women were noted to have a five times higher death rate and black Caribbean women a three times higher death rate than white women. Conversely, Pakistani women had a lower death rate than did white women, although this was not statistically significant. However, the authors of the maternal deaths report noted the uncertainty around their estimates; the number of women in each ethnic group who died was fewer than 10 in all groups except white and black African. This illustrates one of the advantages of complementary reporting of severe maternal morbidity—a higher number of women are affected, so studies have greater power to detect differences between groups.

We have also done an analysis to investigate the potential contribution of other factors associated with severe maternal morbidities to the observed increase in risk associated with non-white ethnicity. Many possible factors exist that might account for the observed ethnic differences in severe maternal mortality. Demographic characteristics are known to affect the risk of individual morbidities—for example, eclampsia occurs more often among younger and older mothers and in primiparous women,19 peripartum hysterectomy occurs more commonly among older women who have previously had a caesarean delivery,20 and older age and obesity (body mass index 30 or over) have been shown to be risk factors for antenatal pulmonary embolism.21 However, adjustment for these factors in a multivariate analysis suggests that the differences in severe maternal morbidity we observed between ethnic groups are not simply due to these factors.

The increased risk of severe maternal morbidity may also be explained by differences in pre-existing maternal medical conditions between ethnic groups, against a background of different genetic and environmental influences. Black and other non-white pregnant women have been shown in an analysis of regional data in the United States to have higher rates of pre-existing hypertension and diabetes,22 both of which may predispose to severe morbidity. However, we have no national data against which to assess this. We did not have sufficient power to detect a significant difference in the pattern of morbidities seen between ethnic groups which might suggest that pre-existing conditions are factors in the ethnic differences in severe maternal morbidity in the UK. However, individual case-control studies of specific morbidities with detailed regression analysis including all potential confounders and risk factors may help to investigate further the role of pre-existing maternal medical conditions.

Several studies have suggested that access to care may be a contributing factor to ethnic differences in health. The most recent UK report concerning maternal deaths showed that some women from ethnic minority backgrounds who died accessed antenatal care either late (after 22 weeks’ gestation) or not at all.1 However, in the Netherlands, women’s delay in consulting a doctor was not considered to be a significant factor in substandard care contributing to maternal death, nor did any difference exist in the proportion of women who delayed consultation between immigrants and non-immigrants.5 The most important factors contributing to substandard care of immigrant women who died in the Netherlands were judged to be delay in recognising symptoms and delay in referral by the general practitioner. A recent national survey of women’s experience of maternity care in the UK reported that women from black and minority ethnic groups were more likely to recognise their pregnancy later, access care later, and consequently book later for antenatal care than were white women.23 Additionally, these women reported that they were less likely to feel that they were treated with respect and talked to in a way they understood by staff during pregnancy, labour and birth, and postnatal care. Their options for care were perceived as more limited, and fewer had the contact details of a midwife available during pregnancy. Although speculative, all these factors could contribute to poorer access to care leading to a higher rate of severe maternal morbidity.

Strengths and limitations

No universally accepted definition of severe maternal morbidity exists. Studies included in a recent systematic review by the World Health Organization were classified in three groups: those that included specific disease conditions, such as pre-eclampsia and haemorrhage; those classed as management specific, including, for example, only women who were admitted to intensive care units; and studies describing organ system dysfunction or failure.9 Studies that combined these groups were also included. We have adopted a combined approach, including specific disease conditions and management approaches, linked directly to the major causes of direct maternal death identified from recent UK national maternal death reports.1 The two other recent national database analyses adopted a similar approach,16 17 using both procedure related and diagnostic codes from ICD-9-CM (international classification of diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification); an ongoing Scottish national study also uses this combined approach.24

Our study, however, used only indicator conditions. We have not made any attempt to comprehensively collect information on all severe maternal morbidities but have concentrated on major conditions causing direct maternal death in the UK. The main group of conditions that we did not study are those which contribute indirectly to maternal deaths—principally cardiac disease, which is the leading indirect cause of maternal death in the UK. However, data from the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths suggest that ethnic differences in cardiac deaths are similar to the differences in deaths from all causes.1 The exclusion of cases of severe maternal morbidity from cardiac disease is thus unlikely to have appreciably affected our estimates of the risk ratio between ethnic groups.

The results of this study would be more robust if national data on maternal ethnicity were available. We estimated denominator information on maternal ethnicity from data that covered 75% of the women we studied; inaccuracies could have been introduced by this estimation method, and the results should be interpreted with caution. In this method, the 1% of women of unknown ethnicity are included in the white ethnic group, as this has been shown to map proportions most accurately to the ethnic profile of infants in the UK population census.14 The proportions we obtained were also compatible with the profile of the ethnicity of infants at birth as defined by the mother.25 The method of estimation may thus slightly underestimate the number of women from minority ethnic groups. Nevertheless, this is unlikely to significantly affect the relative risks we estimated. Of note, the same method was used to generate the denominators for ethnic groups in the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths, allowing direct comparison with our results.

Conclusions and policy implications

We have shown that severe maternal morbidities are significantly more common among women from black African and Caribbean and Pakistani ethnic groups than in white women in the UK. This pattern is very similar to the ethnic differences in maternal death rates observed in the most recent reports from the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health. These differences may be due to the presence of pre-existing maternal medical factors or to factors related to care during pregnancy, labour, and birth, but they are unlikely to be due to differences in age, socioeconomic or smoking status, body mass index, or parity. This highlights to clinicians and policy makers the importance of tailored maternity services and improved access to care for women from ethnic minorities. The availability of national information on the ethnicity of women giving birth in the UK will enable ongoing accurate study of these inequalities and allow for the contributory role of medical or care factors to be clarified.

What is already known on this topic

Several studies have shown inequalities in rates of maternal death among different ethnic minority groups

In countries such as the United Kingdom and United States, maternal deaths are rare

Additional study of non-fatal severe maternal morbidity is increasingly recognised as providing additional information that may guide interventions and prevention

What this study adds

Non-white ethnicity is a significant risk factor for “near miss” maternal morbidity

Black African, black Caribbean, and Pakistani women are particularly at risk

The risk seems to be independent of differences in age, socioeconomic or smoking status, body mass index, or parity and may be related to poorer access to care

This study would not have been possible without the contribution and enthusiasm of the UKOSS reporting clinicians who notified cases and completed the data collection forms. We particularly thank Carole Harris, who administered the data collection, and Ali Macfarlane and Mary Grinsted for providing Hospital Episode Statistics denominator ethnicity data. We also acknowledge the members of the UKOSS Steering Committee who provided advice throughout the study. The support of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Royal College of Midwives, Obstetric Anaesthetists Association, Faculty of Public Health, National Childbirth Trust, and the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health contributed greatly to the success of UKOSS.

Contributors: MK designed the study, coordinated data collection, coded the data, did the analysis, and wrote the first draft of the paper. JJK assisted with the design of the study, supervised the data collection and analysis, and contributed to writing the paper. PS assisted with data coding and did data validation and some analysis. PB had the original idea for the surveillance system, provided advice at every stage of the study, and contributed to the writing and editing of the paper. PB is the guarantor.

Funding: MK is funded by the National Coordinating Centre for Research Capacity Development of the Department of Health. JJK was partially funded by a national public health career scientist award from the Department of Health and NHS R&D (PHCS 022). This paper reports on an independent study which is funded by the Policy Research Programme in the Department of Health. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the department. The authors are independent of all funders.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The London Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee approved UKOSS general methodology (04/MRE02/45) and the studies of individual severe morbidities (04/MRE02/46, 04/MRE02/71, 04/MRE02/72, 04/MRE02/73, 04/MRE02/74).

UKOSS Steering Committee: Catherine Nelson-Piercy (chair), Guys and St Thomas’ Hospital; Jenny Furniss (vice-chair), lay member; Sabaratnam Arulkumaran, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; Jean Chapple, Faculty of Public Health; Cynthia Clarkson, National Childbirth Trust; Natasha Crowcroft, Health Protection Agency; Andrew Dawson, Nevill Hall Hospital; James Dornan, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; Shona Golightly, Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health; Ian Greer, University of York; Mervi Jokinen, Royal College of Midwives; Gwyneth Lewis, Department of Health; Richard Lilford, Department of Public Health and Epidemiology, University of Birmingham; Margaret McGuire, Scottish Executive Health Department; Richard Pebody, Health Protection Agency; Derek Tuffnell, Bradford Hospitals NHS Trust; James Walker, National Patient Safety Agency; Steve Yentis, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital; Carole Harris, National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; Marian Knight, National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; Jennifer Kurinczuk, National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; Peter Brocklehurst, National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b542

References

- 1.Lewis G, ed. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make childhood safer—2003-2005. London: CEMACH, 2007.

- 2.Berg CJ, Chang J, Callaghan WM, Whitehead SJ. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1991-1997. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:289-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuitemaker N, van Roosmalen J, Dekker G, van Dongen P, van Geijn H, Gravenhorst JB. Increased maternal mortality in the Netherlands from group A streptococcal infections. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1998;76:61-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan EA, Hall B, King JF. Maternal deaths in Australia 2003-2005. Sydney: AIHW National Perinatal Statistics Unit, 2007.

- 5.Van Roosmalen J, Schuitemaker NW, Brand R, van Dongen PW, Bennebroek Gravenhorst J. Substandard care in immigrant versus indigenous maternal deaths in the Netherlands. BJOG 2002;109:212-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filippi V, Ronsmans C, Gandaho T, Graham W, Alihonou E, Santos P. Women’s reports of severe (near-miss) obstetric complications in Benin. Stud Fam Plann 2000;31:309-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drife JO. Maternal “near miss” reports? BMJ 1993;307:1087-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waterstone M, Bewley S, Wolfe C. Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: case-control study. BMJ 2001;322:1089-93, discussion 1093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Say L, Pattinson RC, Gulmezoglu AM. WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality: the prevalence of severe acute maternal morbidity (near miss). Reprod Health 2004;1:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ, Tuffnell D, Brocklehurst P. The UK obstetric surveillance system for rare disorders of pregnancy. BJOG 2005;112:263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Office for National Statistics. Ethnic group statistics: a guide for the collection and classification of ethnicity data. Newport: Office for National Statistics, 2003.

- 12.Office for National Statistics. Key population and vital statistics 2005. Newport: Office for National Statistics, 2007.

- 13.The Information Centre for Health and Social Care. Hospital episode statistics 2005-6. www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=537.

- 14.NHS maternity statistics England 2005-6. Statistical bulletin 2006/08. Leeds: Information Centre for Health and Social Care, 2006.

- 15.Office for National Statistics. Standard occupational classification 2000. Newport: Office for National Statistics, 2000.

- 16.Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991-2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:133.e1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen SW, Huang L, Liston R, Heaman M, Baskett T, Rusen ID, et al. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 1991-2001. CMAJ 2005;173:759-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zwart JJ, Richters JM, Ory F, de Vries JI, Bloemenkamp KW, van Roosmalen J. Severe maternal morbidity during pregnancy, delivery and puerperium in the Netherlands: a nationwide population-based study of 371,000 pregnancies. BJOG 2008;115:842-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knight M. Eclampsia in the United Kingdom 2005. BJOG 2007;114:1072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, Brocklehurst P. Cesarean delivery and peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:97-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight M. Antenatal pulmonary embolism: risk factors, management and outcomes. BJOG 2008;115:453-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg TJ, Garbers S, Lipkind H, Chiasson MA. Maternal obesity and diabetes as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes: differences among 4 racial/ethnic groups. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1545-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Redshaw M, Rowe R, Hockley C, Brocklehurst P. Recorded delivery: a national survey of women’s experience of maternity care 2006. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, 2007.

- 24.Brace V, Penney G, Hall M. Quantifying severe maternal morbidity: a Scottish population study. BJOG 2004;111:481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moser K, Stanfield KM, Leon DA. Birthweight and gestational age by ethnic group, England and Wales 2005: introducing new data on births. Health Stat Q 2008;(39):22-31, 34-55. [PubMed]