Abstract

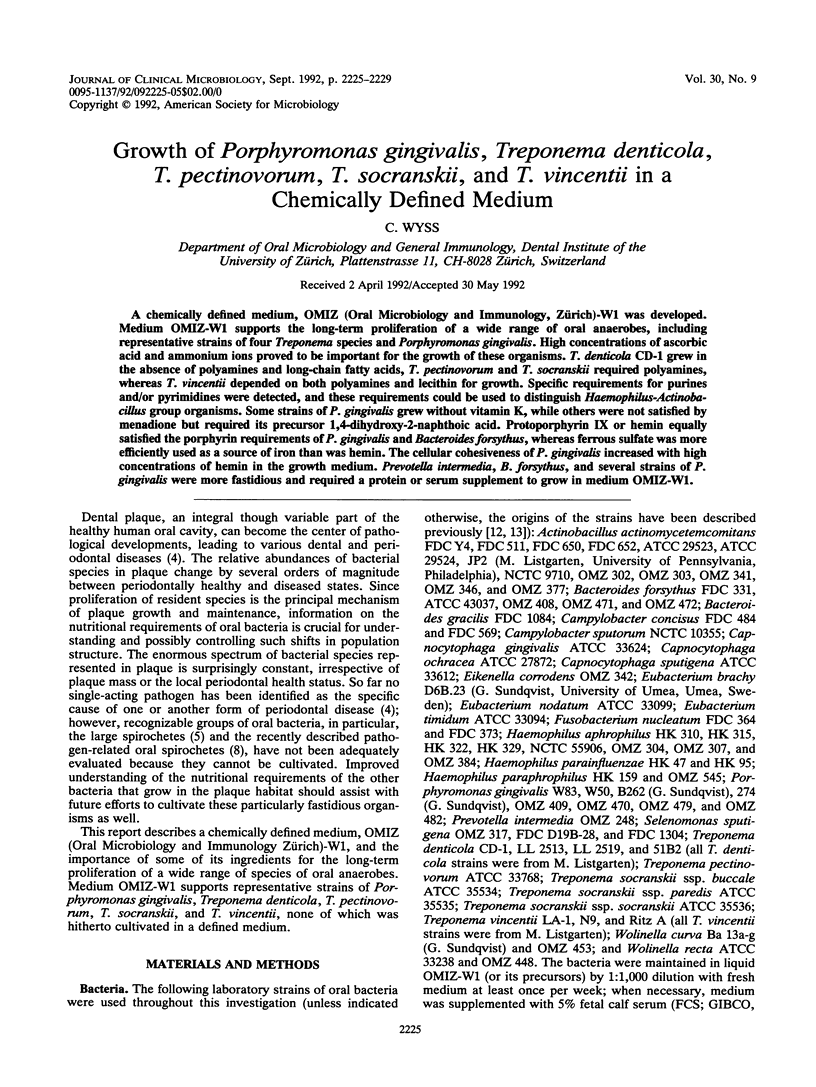

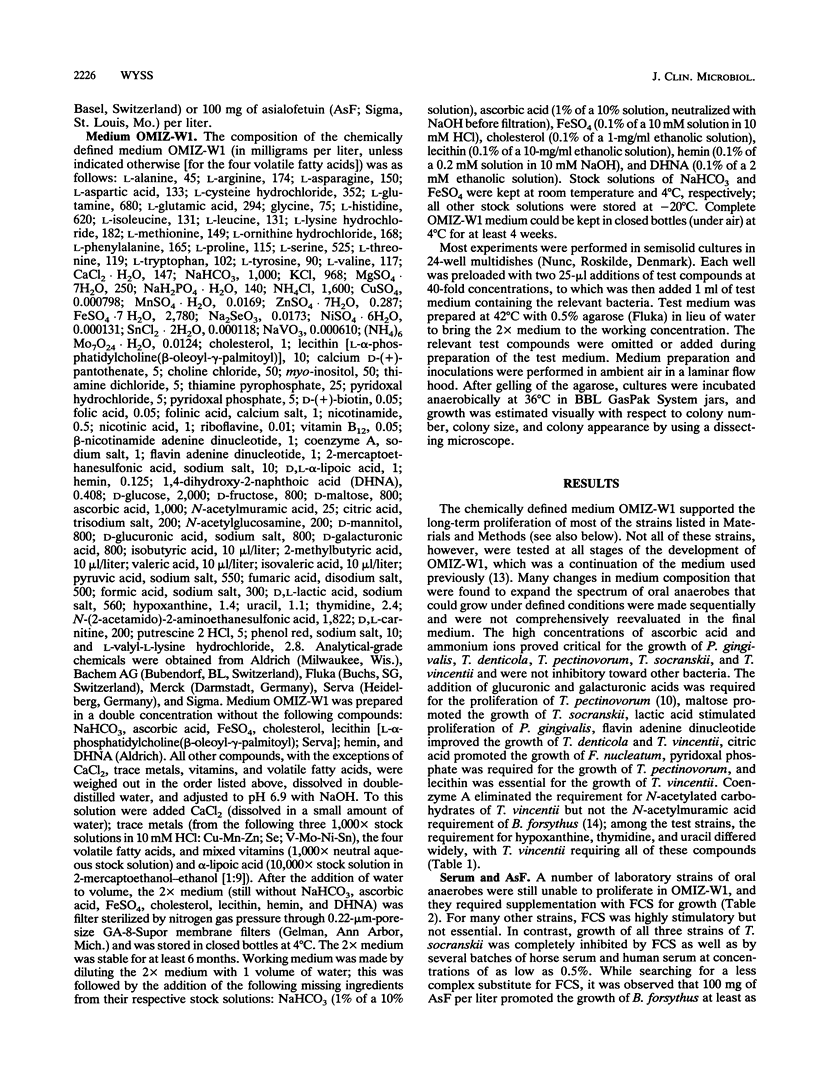

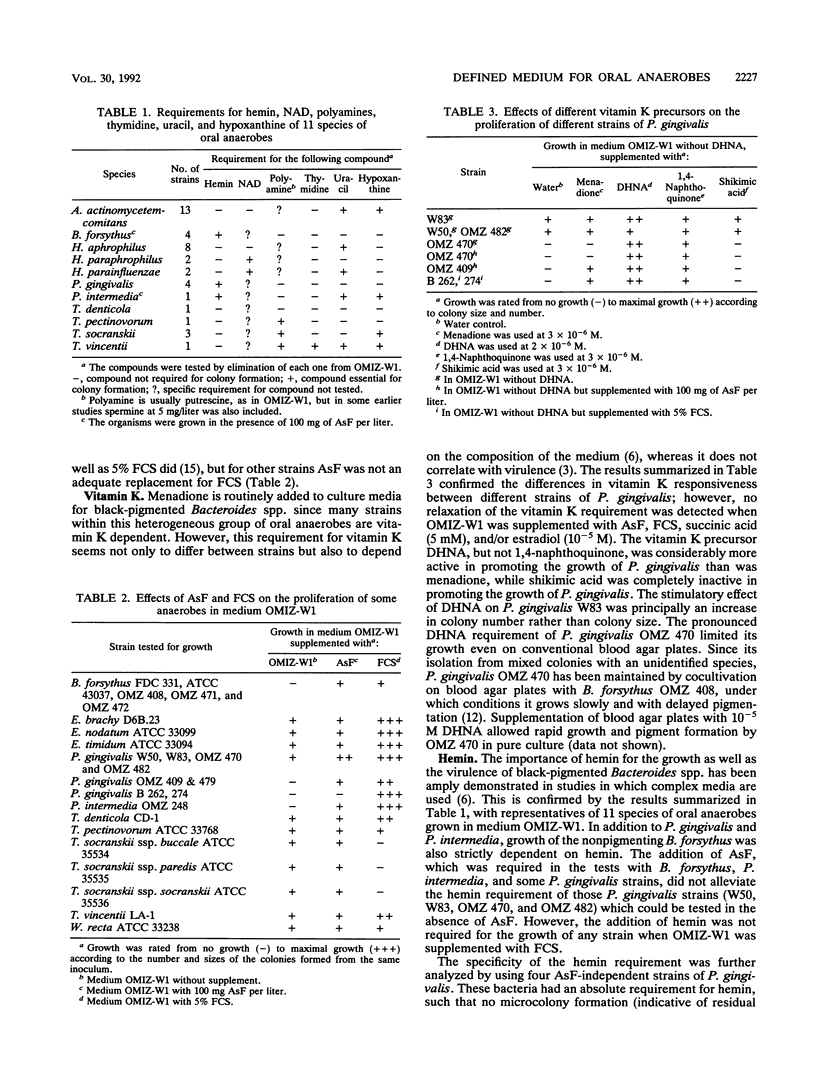

A chemically defined medium, OMIZ (Oral Microbiology and Immunology, Zürich)-W1 was developed. Medium OMIZ-W1 supports the long-term proliferation of a wide range of oral anaerobes, including representative strains of four Treponema species and Porphyromonas gingivalis. High concentrations of ascorbic acid and ammonium ions proved to be important for the growth of these organisms. T. denticola CD-1 grew in the absence of polyamines and long-chain fatty acids, T. pectinovorum and T. socranskii required polyamines, whereas T. vincentii depended on both polyamines and lecithin for growth. Specific requirements for purines and/or pyrimidines were detected, and these requirements could be used to distinguish Haemophilus-Actinobacillus group organisms. Some strains of P. gingivalis grew without vitamin K, while others were not satisfied by menadione but required its precursor 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid. Protoporphyrin IX or hemin equally satisfied the porphyrin requirements of P. gingivalis and Bacteroides forsythus, whereas ferrous sulfate was more efficiently used as a source of iron than was hemin. The cellular cohesiveness of P. gingivalis increased with high concentrations of hemin in the growth medium. Prevotella intermedia, B. forsythus, and several strains of P. gingivalis were more fastidious and required a protein or serum supplement to grow in medium OMIZ-W1.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baker H., DeAngelis B., Frank O. Vitamins and other metabolites in various sera commonly used for cell culturing. Experientia. 1988 Dec 1;44(11-12):1007–1010. doi: 10.1007/BF01939904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramanti T. E., Holt S. C. Roles of porphyrins and host iron transport proteins in regulation of growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. J Bacteriol. 1991 Nov;173(22):7330–7339. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7330-7339.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier D., Mayrand D. Selected characteristics of pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains of Bacteroides gingivalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1987 Apr;25(4):738–740. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.4.738-740.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch R. S., Clarke N. G. Infection and periodontal diseases. Rev Infect Dis. 1989 Sep-Oct;11(5):707–715. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesche W. J. The role of spirochetes in periodontal disease. Adv Dent Res. 1988 Nov;2(2):275–283. doi: 10.1177/08959374880020021201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayrand D., Holt S. C. Biology of asaccharolytic black-pigmented Bacteroides species. Microbiol Rev. 1988 Mar;52(1):134–152. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.1.134-152.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee A. S., McDermid A. S., Baskerville A., Dowsett A. B., Ellwood D. C., Marsh P. D. Effect of hemin on the physiology and virulence of Bacteroides gingivalis W50. Infect Immun. 1986 May;52(2):349–355. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.349-355.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riviere G. R., Weisz K. S., Simonson L. G., Lukehart S. A. Pathogen-related spirochetes identified within gingival tissue from patients with acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. Infect Immun. 1991 Aug;59(8):2653–2657. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2653-2657.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah H. N., Bonnett R., Mateen B., Williams R. A. The porphyrin pigmentation of subspecies of Bacteroides melaninogenicus. Biochem J. 1979 Apr 15;180(1):45–50. doi: 10.1042/bj1800045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn K. G., Smibert R. M. Fatty acid requirement of Treponema denticola and Treponema vincentii. Can J Microbiol. 1982 Mar;28(3):344–350. doi: 10.1139/m82-051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner-Felmayer G., Guggenheim B., Gmür R. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against Bacteroides forsythus and Wolinella recta. J Dent Res. 1988 Mar;67(3):548–553. doi: 10.1177/00220345880670030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss C. Campylobacter-Wolinella group organisms are the only oral bacteria that form arylsulfatase-active colonies on a synthetic indicator medium. Infect Immun. 1989 May;57(5):1380–1383. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.5.1380-1383.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss C. Dependence of proliferation of Bacteroides forsythus on exogenous N-acetylmuramic acid. Infect Immun. 1989 Jun;57(6):1757–1759. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.6.1757-1759.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]