Abstract

Injury to the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb is very common and can be disabling when missed or left untreated. We present a review of literature and our preferred way of management.

Keywords: UCL, Ulnar collateral ligament, Skier’s thumb, Stener lesion, Gamekeeper’s thumb

Introduction

Rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint (MCPJ) is a common hand injury that can lead to long-term problems if inadequately treated [3, 5, 34]. Excessive valgus stress to the base of the thumb may result in disruption of the ulnar collateral ligament complex with or without an avulsion fracture of the base of the proximal phalanx. The injury has two acronyms: the Skier’s thumb suggests an acute injury while the Gamekeeper’s thumb a chronic injury [2, 3, 34]. We present a review of current literature and our experience.

Anatomy

The metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint is a diarthrodial joint. The head of the first metacarpal can vary from dome-shaped to flattened, but the radial condyles of the proximal phalanx are always significantly more prominent on the volar side compared to the ulnar side [37]. The joint is mainly involved in flexion-extension but does also allow rotation, abduction, and adduction. The arc of flexion in a normal MCP joint of the thumb varies considerably from 5° to 115°. The amount of varus or valgus laxity is also variable between normal thumbs and at the different positions of flexion of the same thumb. In full extension, valgus laxity averages 6° and increases to an average of 12° when the joint is in 15° of flexion [4, 10, 38].

The thumb MCP joint is stabilized by static and dynamic stabilizers.

The static restraints of the MCP joint are the volar plate, the dorsal capsule, and the ulnar and radial collateral ligaments. The ulnar collateral ligament complex consists of a proper and an accessory ligament. In flexion, the dorsal capsule and the proper collateral ligament are taut. The proper collateral ligament runs from the middle of the metacarpal head to the palmar aspect of the proximal phalanx. The proper collateral ligament along with the dorsal capsule helps resist palmar subluxation of the proximal phalanx in addition to resisting radially directed forces. In extension, the accessory collateral ligament and the palmar plate are tight. The accessory collateral ligament lies palmar to the proper ligament and is in continuity with it and the volar plate [16, 26]. The role of the accessory collateral ligament in thumb stability has recently been proven [9].

The dynamic stabilizers include the thumb extrinsic muscles (extensor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, and flexor pollicis longus) and intrinsic muscles (abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis, and adductor pollicis). The adductor pollicis inserts into the extensor expansion through its aponeurosis, which normally lies superficial to the joint capsule and the ulnar collateral ligament.

Mechanism of Injury

Disruption of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb MPJ was initially reported by Campbell in 1955. Campbell described laxity of the base of the thumb in Scottish gamekeepers as a result of chronic repetitive valgus strain [2]. As recreational activities prospered in the Western world, the same injury often occurred acutely in skier’s and was initially attributed to the strap at the pole handle [3, 34], but later studies showed that the incidence of the injury remained the same even when new pole designs without a strap were used [6]. Injury rates in skiers are as high as 2.3–4.4 per 1,000 skiing days [6], making it the second most common skiing injury after injury to the medial collateral ligament of the knee. Injuries to the thumb UCL also occur in rugby and other collision sports that involve twisting injuries to the thumb [34]. This injury has even been reported after a handshake [7].

When an acute excessive valgus stress is applied to the thumb MPJ, three injuries can occur: rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament, avulsion fracture of the ulnar–volar base of the proximal phalanx (displaced or not) or both [10]. There is also a rare variation of this injury where the ulnar collateral ligament remains intact, and there is an avulsion fracture involving the volar plate [25, 29].

The incidence of a Stener lesion associated with rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament has been reported to be as high as 52% based on operative findings [25]. Stener lesions are missed despite the advances in imaging and the high suspicion of clinicians [12, 21].

Stener first described the interposition of the adductor aponeurosis and proximal retraction of the ruptured ulnar collateral ligament [35]. In a Stener lesion, the ulnar collateral ligament ruptures from the base of the proximal phalanx (PP) while the thumb is in valgus or abduction and retracts proximally and displaces superficial to the adductor pollicis that contracts to resist the load. In this situation, healing is impossible between the torn proximal end and its footprint at the base of the PP due to the interposed adductor hood. The dorsal capsule may also be torn leading to subluxation of the MCP joint [4, 34].

Clinical Presentation

Unless there is underlying pathology as rheumatoid disease leading to degeneration of the UCL, trauma is required to rupture the UCL complex. This is usually a forced valgus strain to the thumb MCP joint. Common mechanisms of injury include a fall while holding an object that is escaping—for example, a fall while skiing holding a ski pole, a hyperextension or abduction injury trying to catch a ball, or the thumb being caught into an artificial ski slope honeycomb matting. The injury is followed by pain and swelling at the base of the thumb.

Clinical examination may occasionally reveal a tender swelling at the ulnar side of the base of the thumb that represents the displaced ligament that is the Stener lesion. Abrahamsson in 1990 [1] recommended palpation of the displaced ulnar collateral ligament end as a means of differentiating displaced from undisplaced ligaments. This sign was used to decide on conservative or surgical treatment—cast when the end of the ligament is not palpable, thus, nondisplaced; open repair when it is palpable and displaced. In the acute setting, there is pain on palpation, bruising, and swelling. The patient who presents late will have noticed weakness of grip and pinch as well as a sense of instability of the thumb. The injury is easily missed by inexperienced medical personnel.

Clinical and Diagnostic Tests

Before testing for stability, it is important to obtain radiographs to exclude fractures of either the metacarpal or the proximal phalanx.

If there is no associated fracture of the shaft, the thumb MCP joint stability is tested in full flexion, a position where the proper ulnar collateral ligament is tight while stabilizing the thumb metacarpal proximal to the joint to stop rotation and radially angulating the thumb. Laxity over 35° or 15° more than the uninjured side indicates rupture of the proper collateral ligament. The same test is performed in extension, and when positive, it means the accessory ulnar collateral ligament is also torn [4, 29, 35, 38] (Fig. 1). An undisplaced avulsion fracture of the base of the proximal phalanx should not stop the examination since the injury force is always greater than the force applied on clinical examination; thus, it is very unlikely that displacement will occur [15]. Complete rupture of the ligament can coexist with an undisplaced fracture [10, 15, 21].

Figure 1.

Clinical testing for ulnar laxity in flexion.

Imaging

Plain radiographs in both the AP and lateral plane are requested to exclude bone injury. Stress views with local anesthetic may help define the degree of instability (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Bony avulsion of UCL.

Ultrasound has been successfully used in differentiating Stener lesions from simple avulsions of the ulnar collateral ligament [8, 22, 28], but it may be misleading [36]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more accurate (Figs. 3, 4; proximal and distal avulsion) [14, 31]. Arthrography alone or with magnetic resonance has been advocated as method to diagnose Stener lesions [8, 28]. However. no investigation is 100% accurate. The authors do not routinely use MRI but only when clinically in doubt

Figure 3.

MRI of a proximal avulsion.

Figure 4.

MRI of a distal avulsion.

Management

Historically, cast immobilization for 4 to 6 weeks in an acute injury was recommended regardless of the stability of the MCPJ [4, 27]. Currently, most authors have agreed with Stener opinion that 75% of the cases will fail to heal when there is complete rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb [10, 13, 24, 33] though Pichora et al in1989 reported very good results with bracing. Limitations of this study, however, are 25% dropout rates, and at some cases, a 3-month immobilization [30].

Only when the joint is stable in flexion should the injury be treated with immobilization for 4 weeks in either a plaster of Paris or a functional thermoplastic splint with the thumb in slight flexion and neutral regarding varus or valgus [20] immobilizing the MCP joint and allowing motion in the interphalangeal joint. However, if the thumb is stable in extension while lax in flexion, one of the senior authors will attempt to treat the thumb with a 3-week course of cast immobilization. If the stability has not improved at this point, then surgical repair is sought. Surgical treatment in the acute setting is favored since it has excellent results [12].

Under a regional anesthetic, a chevron or lazy “S” incision is used over the ulnar aspect of the base of the thumb. Great care must be taken to identify and protect the dorsal branches of the radial nerve that supply sensation to the ulnar aspect of the thumb (Fig. 5). The proximal edge of the adductor aponeurosis is seen and, if a Stener lesion present (Fig. 6), the obvious oedematous end of the ulnar collateral ligament sticks out proximal to the adductor aponeurosis (Fig. 7). The adductor aponeurosis must be incised longitudinally in a parallel fashion to the extensor pollicis longus. With retraction of the adductor aponeurosis, the dorsal capsule and the collateral ligaments are assessed. In a soft tissue ligament avulsion, a variety of techniques have been used for repair. A pull-out suture technique can be used with a transosseous stainless steel wire or other nonabsorbable suture either tied over bone at the proximal phalanx or tied over a button on the radial side of the MCP joint [15, 34]. Mini anchors have successfully been used to secure the ligament in place without need for drilling two cortices or exposing suture material [17] (Figs. 8, 9). The use of bone anchors is now the most common method of repair in modern practice [12, 17]. If both the proper and accessory ligaments are torn, they must both be repaired to ensure a good result. The proper ligament inserts at the palmar ulnar aspect of the base of the proximal phalanx and should first be secured in place anatomically. Rarely, the palmar plate is reconstructed. However, if required, care should be taken not to over tighten this structure to avoid a fixed flexion contracture. The volar plate is difficult to approach form the ulnar midaxial incision. The accessory ligament will be repaired to its insertion distal and palmar to the proper ligament. Finally the dorsal capsule is sutured, and the adductor aponeurosis repaired. It is recommended by one of the senior authors that repair of the dorsal capsule should be performed in 30° of flexion to prevent postoperative loss of flexion (Fig. 10).

Figure 5.

Doral branch of the radial nerve.

Figure 6.

Adductor aponeurosis.

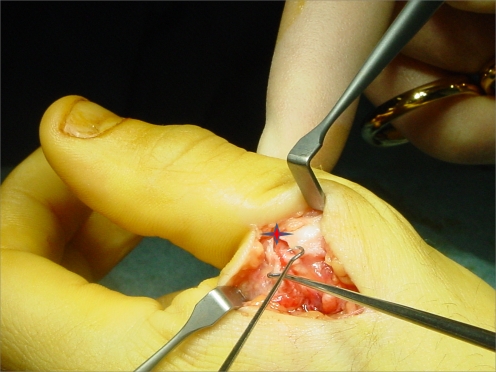

Figure 7.

Stener lesion (adductor aponeurosis is incised).

Figure 8.

Bony anchor inserted at the avulsion site and suture passed through UCL.

Figure 9.

Repair of the avulsion.

Figure 10.

Repair of the adductor aponeurosis.

Infrequently, the ligament is torn in its midsubstance (Fig. 11), in which case, it is directly repaired with mattress 4.0 absorbable sutures with or without the use of a K-wire to stabilize the MCPJ for 4 weeks (Fig. 12).

Figure 11.

Midsubstance tear.

Figure 12.

Use of K-Wires for temporary stabilization.

When there is a fracture of the base of the PP, this is usually avulsed from its ulnopalmar aspect. Smaller fragments can be excised, but larger ones should be reduced and fixed [6, 15] with either a 1.5-mm mini fragment screw or kirschner wires if the bone is too small to accommodate a screw [6]. Tension band wiring has been successfully used for fixation of small fragments. However, it must be stressed that the location of the fragment in the ulnar volar corner of the base of the proximal phalanx often causes difficulty with screw placement due to the poor line of access. Bone anchors are increasingly used for moderate-sized bony fragments either into the avulsion footprint or distal to the footprint and secure the fragment. With more extreme force, a dislocation of the joint may be combined with total rupture of the volar plate. The joint may not maintain stability when reduced and the ligaments repaired; in this case, a wire is used for temporary stabilization of the joint [34].

Classically, a thumb spica splint is used for 4 weeks postoperatively [6, 27], and then active flexion extension is initiated. However, many authors only immobilize the thumb for shorter periods of time; 1 or 2 weeks after which flexion-extension exercises are begun [5, 18, 23] This is our preferred method.

Chronic lesions are more difficult to treat, and in this section, we presume that no arthritis is present. If a classic Stener lesion is found, it can be dissected off the adductor hood, the hood incised, and the ligament reattached with an anchor as in the acute setting. This has been performed by one of the authors on three occasions with good long-term stability. Often, the remnants of the ligament are degenerated. Repair has been tried [19] but usually is not possible. In this situation, the UCL is reconstructed using a tendon graft. The most common donor is the palmaris longus tendon followed by a strip of the flexor carpi radialis or ulnaris or the extensor pollicis brevis [11, 32]. The reconstruction can be performed in any bony tunnel configuration though it was shown that a triangular configuration with apex proximal stabilizes the thumb MCP joint with good results in maintaining the flexion or extension arc.

Conclusions

A neglected, undertreated, or missed injury of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb may lead to significant disability and chronic pain due to instability. Some authors suggest conservative treatment with cast or splint immobilization for complete undisplaced ruptures of the UCL as suggested by Abrahamsson regardless of the instability [1, 12]. However, the outcome may not always be favorable; therefore, this approach is not largely accepted [12, 35].

Our opinion is that acute complete ruptures of the UCL with associated joint laxity should be repaired. Early mobilization after stable anatomical repair is associated with excellent return of movement and strength.

References

- 1.Abrahamsson SO, Sollerman C, Lundborg G, et al. Diagnosis of displaced ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1990;15:457–60. doi:10.1016/0363-5023(90)90059-Z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Campbell CS. Gamekeeper’s thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1955;37-B(1):148–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Carr D, Johnson RJ, Pope MH. Upper extremity injuries in skiing. Am J Sports Med. 1981;9:378–83. doi:10.1177/036354658100900607. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Coonrad RW, Goldner JL. A study of the pathological findings and treatment in soft-tissue injury of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint: with a clinical study of the normal range of motion in one thousand thumbs and a study of post mortem findings of ligamentous structures in relation to function. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1968;50:439–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Demirel M, Turhan E, Dereboy F. Surgical treatment of skier’s thumb injuries. Case Rep Rev Lit The Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73–5:818–21. [PubMed]

- 6.Derkash RS, Matyas JR, Weaver JK, et al. Acute surgical repair of the skier’s thumb. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;216:29–33, March. [PubMed]

- 7.Dey R, Green AD. The danger in a handshake—an unusual case of ulnar collateral ligament rupture injury. Int J Care Injured. 2003;34:535–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ebrahim FS, De Maeseneer M, Jager T. US diagnosis of UCL tears of the thumb and Stener lesions: technique, pattern-based approach, and differential diagnosis. Radiographics 2006;26(4):1007–20. doi:10.1148/rg.264055117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Fraser B, Veitch J, Firoozbakhsh K. Assessment of rotational instability with disruption of the accessory collateral ligament of the thumb MCP joint: a biomechanical study hand online first. Hand 2008;3:224–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Giele H, Martin J. The two level ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg J Br Soc Surg Hand. 2003;28(1):92–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Glickel SZ, Malerich M, Pearce SM, Littler JW. Ligament replacement for chronic instability of the ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1993;18:930–41. doi:10.1016/0363-5023(93)90068-E. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Glickel S, Barron OA, Catalano LW. Dislocations and ligament injuries in the digits, green, hotchkiss, pederson, wollfe: greens operative hand surgery. 5th ed. New York: Churchill-Livingstone; 2005. p. 367–73.

- 13.Harper MT, Chandnani VP, Spaeth J, et al. Gamekeeper thumb: diagnosis of ulnar collateral ligament injury using magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography and stress radiography. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;6(2):322–8. doi:10.1002/jmri.1880060211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Hergan K, Mittler C, Oser W. Ulnar collateral ligament: differentiation of displaced and nondisplaced tears with US and MR imaging. Radiology 1995;194(1):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Heyman P. Injuries to the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5:224–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Heyman P, Gelberman RH, Duncan K, Hipp JA. Injuries of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. Biomechanical and prospective clinical studies on the usefulness of valgus stress testing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;292:165–71. [PubMed]

- 17.Huber J, Bickert B, Germann G. The Mitek mini anchor in the treatment of the gamekeeper’s thumb. Eur J Plast Surg. 1997;20:251–5. doi:10.1007/BF01159486. [DOI]

- 18.Husband JB, McPherson SA. Bony Skier’s Thumb Injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;327:79–84. doi:10.1097/00003086-199606000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Isani A, Melone CP Jr. Ligamentous injuries of the hand in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 1986;5:757–72. [PubMed]

- 20.Jones S, Crawford I. Plaster or functional splint in gamekeepers thumb. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:324–30. doi:10.1136/emj.19.4.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Kaplan SJ. The Stener lesion revisited: A case report. J Hand Surg. 1998;23(5):833–6, September. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Koslowsky TC, Mader K, Gausepohl T, et al. Ultrasonographic stress test of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;427:115–9. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000136907.90559.5c. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Lane LB. Acute Grade III ulnar collateral ligament ruptures. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:234–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Lee SK, Kubiak EN, Lawler E, et al. Thumb metacarpophalangeal ulnar collateral ligament injuries: a biomechanical simulation study of four static reconstructions. J Hand Surg. 2005;30(5):1056–60, September. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Louis DS, Huebner JJ, Hankin FM. Rupture and displacement of the ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68-A:1320–6. [PubMed]

- 26.Minami A, An KA, Cooney WP, et al. Ligamentous structures of the metacarpophalangeal joint: a quantitative anatomic study. J Orthop Res. 1984;1(4):361–8. doi:10.1002/jor.1100010404. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Neviaser RJ, Wilson JN, Lievano A. Rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb (gamekeeper’s thumb): correction by dynamic repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:1357–64. [PubMed]

- 28.Noszian I, et al. Ulnar collateral ligament: differentiation of displaced and nondisplaced tears with US. Radiology 1995;194:61–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Palmer AK, Louis DS. Assessing ulnar instability of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1978;3(6):542–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Pichora DR, McMurtry RY, Bell MJ. Gamekeepers thumb: a prospective study of functional bracing. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1989;14(3):567–73, May. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Romano WM, Garvin G, Bhayana, et al. The spectrum of ulnar collateral ligament injuries as viewed on magnetic resonance imaging of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. CarJ 2003;544:243–8, October. [PubMed]

- 32.Sakellarides HT. DeWeese Instability of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. Reconstruction of the collateral ligaments using the extensor pollicis brevis tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:106–12. [PubMed]

- 33.Sartoris AJM, et al. Gamekeeper thumb: comparison of MR arthrography with conventional arthrography and MR imaging in cadavers. Radiology 1998;206(3):737–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Smith RJ. Post-traumatic instability of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:14–21. [PubMed]

- 35.Stener B. Displacement of the ruptures ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1962;44-B:869–79.

- 36.Susic D, Hansen BR, Hansen TB. Ultrasonography may be misleading in the diagnosis of ruptured and dislocated ulnar collateral ligaments of the thumb. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1999;33(3):319–20. doi:10.1080/02844319950159307. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Yamanaka K, Yoshida K, Inoue H, et al. Locking of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:782–7. [PubMed]

- 38.Yoshida R, House HO, Patterson RM, et al. Motion and morphology of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. J Hand Surg. 2003;28–5:753–7, September. [DOI] [PubMed]