Abstract

Virtual high throughput screening (VHTS) was performed to assess possible interactions which might occur between commercially available triphenylphosphonium (TPP) cations and estrogen receptor α (ERα) that could be exploited to design novel ERα modulators. One application of TPP cations is for delivering bioactive molecules to targets in mitochondria as the large membrane potential of mitochondria leads cations to accumulate inside them. The estrogen receptors (ERs) α and β, normally activated by the endogenous hormone 17β‐estradiol, are responsible for controlling transcription of nuclear DNA necessary for human development and reproduction. ERs are also associated with the plasma membrane and have been found in the mitochondria of a variety of cell types. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are synthetic compounds which are used to modulate ER activity. Different SERMs display varying combinations of agonistic, antagonistic and neutral effects upon estrogen receptors depending upon the tissue type and cellular location of the receptor. Thus, they are being employed to treat a range of ER‐related disorders. A common feature shared by many SERMs is the close arrangement of three aromatic rings similar to TPP cations. Given this structural similarity, the estrogenic activity of triphenyl phosphonium salts was investigated using the automated docking program eHiTS. Compounds were docked into ten different crystal structures of ERα. Structures were chosen based upon eHiTS ability to accurately identify the majority of estrogenically active compounds given a set of active and decoy molecules. The results of the VHTS suggest hybrids of TPP cations and known SERMs could serve as potent mitochondrial SERMs.

Keywords: Estrogen receptor, SERMs, molecular docking, eHiTS, triphenylphosphonium salts, mitochondria

Background

The estrogen receptors (ERs) α and β are intracellular proteins responsible for controlling transcription of genes necessary for human development and reproduction. ER activity is normally modulated by the endogenous hormone 17β‐estradiol (E2) which binds to nuclear ERs resulting in recruitment of coregulatory complexes. Due to the important role the ER signaling networks play in developmental, reproductive, skeletal, neural, and cardiovascular processes, irregularities in ER activity can lead to a number of conditions including breast, ovarian, colon, prostate, and endometrial cancers. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as tamoxifen and raloxifene have been successful in the treatment and prevention of both breast cancer and osteoporosis [1]. SERMs are compounds which display agonist, antagonist, or neutral effects on ER activity dependent upon the specific ER subtype and cell type in which the estrogen receptor is present.

In addition to being found in the nucleus as well as in and adjacent to the plasma membrane, ERα and ERβ have also been located in the mitochondria of a variety of cell types [2]. E2 has been known to have an inhibitory effect on apoptosis and mitrochondrial ERs are believed to make a direct, specific contribution to this. Nuclear ERs when activated bind with Estrogen Response Elements in nuclear DNA and sequences similar to these EREs have been found in mitochondrial DNA. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays and surface plasmon resonance studies have revealed that mitochondrial ERs do in fact bind to these sites [3]. Current evidence also supports mitochondrial ERβ serving an anti‐apopototic role in rat heart muscle subjected to trauma and hemorrhage and activation of mitochondrial ERs having a protective effect on cerebral blood vessels and cultured endothelial cells. More investigation is required to further elucidate the specific mechanisms by which mitochondrial ERs contribute to cellular function and dysfunction.

One possible way to elucidate specific roles that mitochondrial ERs have in cellular function would be to design a small molecule which would be capable of selectively affecting mitochondrial ERs. One method for delivering small molecules to the mitochondria is to exploit the fact that there is a large membrane potential of 150‐180 mV across the mitochondrial inner membrane, with the inside of mitochondria being negatively charged [4]. Due to this potential gradient, lipophilic cations, which are able to pass through lipid bilayers due to their dispersed charge, are able to accumulate 100‐500 fold inside the mitochondria matrix [5]. This technique has been employed to prevent mitochondrial oxidative damage by conjugating anti‐oxidants to the triphenylphosphonium (TPP) cation [6].

If TPP cations existed which showed estrogenic (or antiestrogenic) activity, by exploiting the 100‐500 fold accumulation of lipophilic cations inside mitochondria, it may be possible to rationally design a SERM selective towards mitochondrial ERs. Here, we employ molecular docking to consider possible interactions a set of commercially available TPP cations could have with ERα. A set of 314 compounds available from Sigma‐Aldrich were screened in silico using the automated docking and scoring program eHiTS (electronic High Throughput Screening) from SimBioSys Inc. [7,8]. Compounds were docked into ten different X‐ray crystallography structures of ERα from the Protein Data Bank [9]. A test set of known ERα binders and decoy molecules was created in order to test eHiTS ability to accurately dock and score compounds. Ten X‐ray crystallography structures of ERα from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) were chosen which eHiTS was able to use to identify the majority of active compounds from the test set. After docking and scoring the set of TPP cations, the orientations of top scoring molecules were examined to consider which molecules would be best for further optimization. While a variety of TPP cations with various moieties may possibly bind with ERα with the TPP cation part of the compound inside of the ligand binding pocket of ERα, results suggest that one might be able to produce strong ERα binders which could target mitochondria by conjugating known SERMs to the TPP cation. In vitro testing has yet to be conducted to verify the estrogenic activity of these compounds. If some of these compounds do show estrogenic activity, further work should be done to optimize these structures to maximize activity and determine if there is a concentration range where a compound might affect principally mitochondrial ERα.

Methodology

All docking and scoring was performed with the software eHiTS (electronic High Throughput Screening) Lightning (Version 8.0.rc2.4) by SimBioSys Inc. running on a Sony PlayStation 3. eHiTS docks small molecules into a protein structure by first dividing up the small molecules into rigid fragments and flexible chains. The rigid fragments are docked independently into the receptor site, generating multiple poses which are stored in DockTable, an SQL database so that common molecular fragments that occur in multiple small molecules can be reused. A graph matching algorithm enumerates all compatible fragment pose combinations and then flexible chains are fitted between the rigid fragment poses to satisfy steric criteria imposed by the fragments and the receptor site. Finally, local minimization is performed using a modified Powell's method on the reconstructed structures to obtain the final poses. An empirical scoring function is used several times during the algorithm including during evaluation of rigid poses, selection of best graph matching solutions, flexible chain fitting, and final local optimization.

To handle the problem of protein flexibility, eHiTS provides a “soft” representation of the protein structure in three respects. The eHiTS scoring function utilizes the temperature factor information provided in the PDB files to attempt in its gauging of the interaction as well as considering the probability of the atom positions to create a derived empirical scoring function. eHiTS rotates the hydroxyl groups of the serine, threonine and tyrosine residues of the protein and also the -NH3+ group of lysine. Thus, the interaction flexibility of these is considered even though eHiTS does not move the heavy atoms of the main or side chains during this process. Furthermore, the steric clash, or van der Waals potential, is considered with a “soft” quadratic potential as opposed to the harder 6‐12 potential often employed in force fields. The top scoring thirty‐two orientations for each compound successfully docked are saved and the compounds are ranked by the top scoring pose calculated for each structure.

Two sets of compounds were assembled using data from the Binding Database [10,11]. One set of compounds contained active compounds which were reported as having an inhibition constant Ki of less than 10 nM for ERα [12,13,14,15,16]. The other set of compounds was a set of decoy molecules which were found to show no activity even at concentrations greater than 100000 nM [17]. Ten PDB structures were chosen which were able to accurately rank the majority of actives from the decoy molecules ‐‐ 1R5K, 1SJ0, 1XP1, 1XP6, 1XP9, 1XPC, 1YIM, 1YIN, 2OUZ, and 3ERT. To validate this, the best (i.e. minimum score) a molecule received across any of the above structures was taken and a Student's t‐test was performed comparing the scores between active and decoy molecules. A p‐value of less than 0.0001 suggested that there was a significant difference between the scores ctives received and the scores decoys received with the active molecules having better scores.

A library of triphenylphosphonium salts and cations was assembled through a substructure search of the Sigma‐Aldrich catalogue. Anions were removed from the salts and redundant compounds were removed to form a library of 315 compounds. 3D coordinates for the structures were generated using the Molconvert utility from ChemAxon [18]. Compounds were docked into the ten X‐ray structures with standard settings in eHiTS. PyMol from DeLano Scientific was used for visual inspection of results and graphical presentations. After observing an interesting orientation of one of the higher scoring phosphonium cations, a structure which combined the phosphonium cation with the co‐crystalized ligand was also tested using the same settings.

Discussion

eHiTS scoring function is given in units of pKi and thus more negatively scoring compounds are theoretically better binders. However, reliably accurate scoring of compounds aligned into protein structures using docking programs continues to be a problem [19,20]. In general, a “good” performing scoring function should be able to rank ligands majoritively over non‐ligands given a set of actives and decoys for a particular protein structure. Performance among docking programs and scoring functions tends to vary depending upon the protein structure. Reliably ranking active ligands in order of binding affinity is rarely achievable. eHiTS features a customizable scoring function which can be trained using either “Validation Training,” “Enrichment Training,” or both. Neither of these features was utilized however due to technical issues which were encountered while using eHiTS Lightning.

Instead, a set of active compounds (defined as compounds with reported Ki for estrogen receptor α less than 10 nM) and decoy compounds (defined as compounds with Ki for estrogen receptor α greater than 100000nM) were assembled using results on BindingDB.org. The active set included fourteen compounds and the decoy set included twenty compounds. Using eHiTS to dock and score these compounds into various PDB structures of estrogen receptor α structures, ten PDB structures were chosen which returned scores which ranked the majority of active compounds above decoy molecules without performing additional training of eHiTS' scoring function. Shown in Table 1 are selected results from eight of those structures, including the top two scoring and worst scoring active compounds along with the top two scoring and worst scoring decoy molecules.

Also shown in Table 1 (supplementary material) are all TPP cations tested which scored better than -12 on at least one of the ERα structures used in this study. Originally, it was hypothesized that eHiTS might orient the TPP cations with conjugated moieties in the ERα ligand binding pocket such that the TPP cation part of the compound would be inside the pocket with the moiety extending outward to the surface of the receptor. In this way, the compound would resemble the binding pose of many known SERMs which have a clustered ring system inside the pocket with a side arm extending outward (see Figure 1a). However, it was found that most of the top scoring poses had the moiety inside the pocket, pointing towards or wrapping around the side of the pocket (see Figures 1b, 1c, 1d). While these compounds appeared to score well, none were in the range of the best performing known SERMs from the active set. While this does not eliminate the possibility that some of the TPP cations might have ERα modulating abilities, altering a high scoring TPP cation to improve its score to the range of the higher performing known actives should increase the likelihood of producing an active compound.

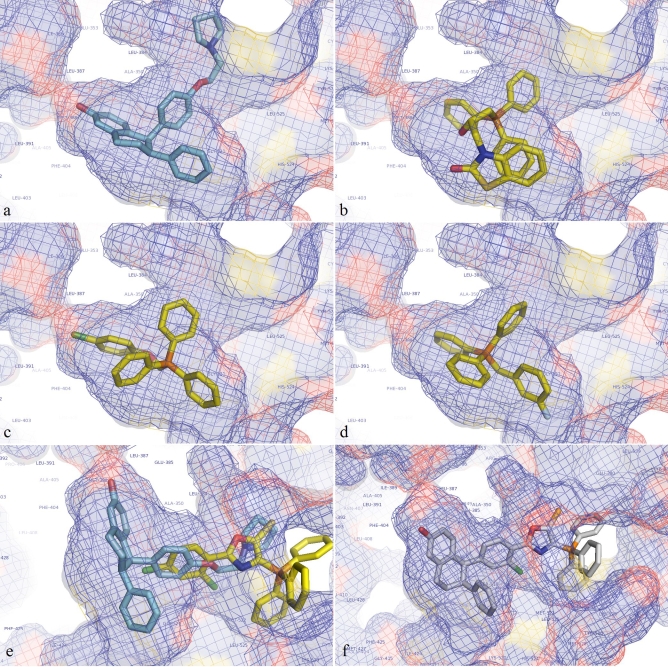

Figure 1.

(a) Lasofoxifene as it was found when co‐crystalized with ERα (PDB structure 2OUZ). (b, c, d) Various topscoring TPP cations docked into the ligand binding pocket of ERα structure 2OUZ after the co‐crystalized ligand has been removed. Note how the moiety bound to the TPP cation is oriented towards the side of the pocket and now facing out of the cavity (towards the surface of ERα). (e) A TPP cation which scored well (eHiTS score = -11.035) with the TPP cation part on the surface of the receptor with the bound moiety extending inwards. It was docked without lasofoixfene being inside the pocket, although lasofoxifene is shown with it to show the overlap. (f) Lasofoxifene/TPP cation hybrid compound as it docked into 2OUZ (eHiTS score = -14.119).

An opportunity for this path to be explored arose when some TPP cations were found to be oriented with the TPP cation on the outside of the ligand binding pocket with the bound moiety extending inwards (see Figure 1e). One TPP cation was chosen which had this orientation when docked into PDB structure 2OUZ and was found to have a convenient overlap with the co‐crystalized ligand in that structure. The original TPP cation had a score of -11.035 when docked into 2OUZ. The co‐crystalized ligand of 2OUZ (lasofoxifene) had a score of -12.483 when redocked into the structure with an RMS difference of 1.364 angstroms off from the original co‐crystalized structure. The hybrid structure produced by combining the TPP cation seen in Figure 1e with lasofoxifene was found to have the significantly better score of -14.119 when docked into 2OUZ (see Figure 1f), putting it into the same range as the top perform actives. However, when this hybrid molecule was docked into other ERα structures evaluated in this study it was not scored as well. Only in PDB structure 1SJ0 did it score in the active range. In 1XPC it docked but scored poorly and in the other structures eHiTS returned a score of zero. Further testing of TPP/SERM hybrids to produce more realiable compounds should be a future direction of study.

Conclusion

Due to the importance of proper ER functioning in a multitude of bodily processes, compounds which can selectively modify ERs can serve as important therapeutic tools. Mitochondrial ERs are known to play roles in cellular processes, although their specific pathways are still being uncovered. The design of a lipophilic cationic SERM from TPP cations may provide a novel method for probing the mechanisms of mitochondrial ERs. In silico screening of commercially available TPP cations using eHiTS suggested that TPP cations could bind with ERα, although not necessarily in the hypothesized orientation with the moiety bound to the TPP cation oriented outward towards the surface of the receptor. However, docking results suggested that another strategy for optimizing TPP cations to act as estrogen receptor modulators is to use a fragment‐based approach in order to produce TPP/SERM hybrids. With the SERM part of the compound inside of the ERα ligand binding pocket and the TPP cation filling the opening to the pocket, this hybrid molecule could potentially bind more tightly to ERα than either of the individual components could. Thus, hybrid molecules incorporating known SERM motifs could serve as high affinity estrogen receptor ligands. This serves as a future direction of study for designing novel SERMs, particularly as a lipophilic cationic SERM could function as a mitochondrial SERM.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by operating grants from the Rhode Island Science and Technology Advisory Council (RIRA #2008‐44) and the Rhode Island IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (5P20RR016457‐07). The authors would also like to thank SimBioSys Inc. for a free academic license to use eHiTS and the privilege to beta test eHiTS Lightning.

Footnotes

Citation:Salisbury & Williams, Bioinformation 3(7): 303-307 (2009)

References

- 1.Jordan VC, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(5):350. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yager JD, et al. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;18(3):89. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Psarra G, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783(1):1. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy MP, et al. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15(8):326. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross MF, et al. Biochem J. 2008;411(3):633. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy MP, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:1028. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zsoldos Z, et al. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2006;7(5):421. doi: 10.2174/138920306778559412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zsoldos Z, et al. J Mol Graphics Modell. 2007;26(1):198. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman HM, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, et al. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(1):130. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu T, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D198. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hummel W, et al. J Med Chem. 2005;48(22):6772. doi: 10.1021/jm050723z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson TI, et al. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17(13):3570. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson TI, et al. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17(17):4824. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norman H, et al. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17(18):5082. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou HB, et al. J Med Chem. 2007;50(2):399. doi: 10.1021/jm061035y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Medina P, et al. J Med Chem. 2005;48(1):287. doi: 10.1021/jm0498194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. http://www.chemaxon.com/marvin/help/applications/molconvert.html

- 19.Jain A. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2006;7(5):407. doi: 10.2174/138920306778559395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moitessier M, et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:S7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.