Abstract

Ca2+ entry through store-operated Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels initiates key functions such as gene expression and exocytosis of inflammatory mediators. Activation of CRAC channels by store depletion involves the redistribution of the ER Ca2+ sensor, stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), to peripheral sites where it co-clusters with the CRAC channel subunit, Orai1. However, how STIM1 communicates with the CRAC channel and initiates the subsequent events culminating in channel opening is unclear. Here, we show that redistribution of STIM1 and Orai1 occurs in parallel with a pronounced increase in fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between STIM1 and Orai1, supporting the idea that activation of CRAC channels occurs through physical interactions with STIM1. Co-expression of Orai1–CFP and Orai1–YFP results in a high degree of FRET in resting cells, indicating that Orai1 exists as a multimer. However, store depletion triggers molecular rearrangements in Orai1 resulting in a decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET. The decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET is not seen in the absence of STIM1 co-expression and is abolished in Orai1 mutants with impaired STIM1 interaction. Both the STIM1–Orai1 interaction as well as the molecular rearrangements in Orai1 are altered by two powerful modulators of CRAC channel activity: extracellular Ca2+ and 2-APB. These studies identify a STIM1-dependent conformational change in Orai1 during the activation of CRAC channels and reveal that STIM1–Orai1 interaction and the downstream Orai1 conformational change can be independently modulated to fine-tune CRAC channel activity.

The depletion of Ca2+ from the ER in many cells triggers Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane (PM) through ion channels termed store-operated channels (SOCs). One prototypic SOC subtype, the CRAC channel, is expressed by T cells, mast cells and other haematopoetic cells, and mediates critical functions such as gene expression, motility and the secretion of inflammatory mediators (Lewis, 2001; Parekh & Putney, 2005; Parekh, 2007). Mutations in CRAC channels lead to loss of CRAC currents, defective T cell activation, and a devastating propensity for fungal and viral infections in human patients, underscoring their pivotal importance for human physiology (Partiseti et al. 1994; Feske et al. 2001,2006). However, despite intense efforts spanning nearly two decades, the mechanism by which store depletion leads to channel activation and the molecular mechanisms of channel regulation remain incompletely understood.

The recent discoveries of STIM1 as the ER Ca2+ sensor and Orai1 as a key CRAC channel pore subunit have inspired excited speculation that the sequence of molecular steps linking store depletion to CRAC channel activation may be finally elucidated. STIM1 is a single-pass transmembrane protein with several functional domains including a luminal EF-hand motif that senses the ER Ca2+ concentration and multiple protein–protein interaction motifs. STIM1 is distributed diffusely throughout the ER membrane in resting cells. However, store depletion triggers a coordinated series of events beginning with STIM1 oligomerization followed by its redistribution and accumulation into discrete puncta at junctional ER sites where the ER tubules and the PM are within 20 nm of each other (Liou et al. 2005,2007; Zhang et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2006; Luik et al. 2006,2008). Orai1, which is also diffusely distributed in the plasma membrane at rest, forms puncta and co-localizes with STIM1 following store depletion (Luik et al. 2006; Xu et al. 2006). Collectively, these results have led to the view that store depletion causes the redistribution of STIM1 and Orai1 to closely apposed clusters in the ER and plasma membranes, thereby enabling unknown interactions to occur between CRAC channels and ER proteins culminating in channel activation (Lewis, 2007).

While these studies have provided insight into the early events surrounding the SOC activation process, precisely how STIM1 communicates with the CRAC channel and initiates the subsequent events culminating in channel opening is unclear. A direct physical association of CRAC channels with ER proteins has been widely considered and is supported by several lines of evidence including a narrow separation between the junctional ER and the PM (Wu et al. 2006), the ability of over-expressed STIM1 and Orai1 to co-immunoprecipitate each other (Vig et al. 2006; Yeromin et al. 2006), and by the recent demonstration of FRET between fluorophores fused to STIM1 and Orai1 (Muik et al. 2008). However, there is also evidence for lack of STIM1–Orai1 co-immunopreciptation (Gwack et al. 2007), and some reports have suggested that instead, store depletion leads to STIM1-dependent formation of a diffusible messenger that is responsible for CRAC channel activation (Csutora et al. 2008). In addition, it seems likely that the arrival of STIM1 to the ER–PM junctions may change the conformational state of the CRAC channel, but this has never been examined. The identity of such conformational changes preceding channel opening may be important not only for understanding the biophysics of CRAC channel activation but also for elucidating the mechanism of channel modulation by drugs and intracellular second messengers.

Apart from activation by store depletion, the CRAC channel is also the target of a rich array of other regulatory influences. One well-studied form of modulation involves facilitation by extracellular Ca2+ via an effect termed calcium-dependent potentiation (CDP) (Christian et al. 1996; Zweifach & Lewis, 1996; Su et al. 2004). The effects of CDP are striking in that steady-state channel activity measured by monovalent currents in solutions devoid of divalent ions is less than 20% of that observed in the presence of Ca2+ (Lepple-Wienhues & Cahalan, 1996; Prakriya & Lewis, 2002). A second, more perplexing mode of regulation is that mediated by the compound 2-APB. 2-APB elicits dual effects, strongly enhancing SOC activity by up to 5-fold at low concentrations (1–10 μm), but transiently enhancing and then inhibiting SOC activity at high concentrations (> 20 μm) (Prakriya & Lewis, 2001; Ma et al. 2002). The molecular mechanisms of these forms of regulation remain unclear.

In this study, we have employed FRET to investigate the association of STIM1 with Orai1 and interactions between Orai1 subunits to probe the events underlying the activation of CRAC channels following store depletion. FRET is a sensitive distance-dependent proximity probe, allowing the detection of donor–acceptor interactions on a molecular scale (10–100 Å), and has been widely employed to study protein–protein interactions and to gain insight into atomic-scale conformational rearrangements in ion channels (Gandhi & Isacoff, 2005). We find that store depletion triggers a pronounced enhancement of STIM1–Orai1 FRET and a decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET, both of which occur in parallel with the redistribution of STIM1 and Orai1. Using these FRET measurements to monitor the association of STIM1 with Orai1 and subsequent molecular rearrangements in the CRAC channel, we examined the protein targets of channel regulation by extracellular Ca2+ and 2-APB. Our results support the local activation of CRAC channels through physical interactions with ER proteins and identify STIM1–Orai1 interaction and Orai1 conformational change as targets for modulation of CRAC channel activity.

Methods

Cells

HEK293 cells were maintained in suspension in log-phase growth at 37°C in 5% CO2 and grown in a medium consisting of CD293 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 4 mm GlutaMAX (Invitrogen). To prepare them for imaging and electrophysiology, cells were plated on to poly d-lysine-coated coverslips at the time of passage, and then grown until the time of transfection (24–48 h later) in FBS-supplemented medium consisting of 44% DMEM (Mediatech) and 44% Ham's F12 (Mediatech), 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone), 2 mm glutamine, 50 U ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin.

Plasmids and transfections

The fusion proteins Orai1–CFP (cyan fluorescent protein), Orai1–YFP (yellow fluorescent protein), STIM1–CFP and STIM1–YFP were generated by amplifying full-length Orai1 and STIM1 cDNA via PCR and cloning into the pECFP-N1 and pEYFP-N1 vectors (Clontech), in frame with CFP or YFP, resulting in the placement of the tags at the C-terminus of Orai1 and STIM1. The Orai1 coding sequence was cloned between the EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites in the vectors. Likewise, STIM1 was cloned between the EcoRI and BamHI, and between the NheI and AgeI restriction sites of the pEYFP-N1 and pECFP-N1 vectors, respectively. N-terminally tagged CFP–Orai1 was purchased from GeneCopoeia, Inc. Site-directed mutagenesis to generate the C-terminus Orai1 mutations and the D76A STIM1 mutation was performed on the C-terminally tagged Orai1 and STIM1 plasmids using the QuikChangeSite-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). HEK293 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), with 100 ng Orai1–CFP and 300 ng STIM1–YFP per 12 mm coverslip. For the experiments on Orai1–Orai1 FRET, cells were transfected with 100 ng of Orai1–CFP and 100 ng of Orai1–YFP, together with 300 ng of mCherry–STIM1 (kind gift of Richard Lewis, Stanford University, CA, USA) per coverslip. In this construct, mCherry is adjacent to the signal sequence in the N-terminus of STIM1 located within the ER lumen (Luik et al. 2006). In CXCR4–CFP, the flourophore is at the intracellular C-terminus of CXCR4 (Toth et al. 2004). Orai1 cDNA amounts were lowered (to 10 or 25 ng per coverslip) in some experiments as indicated in the figure legends. Unlabelled STIM1 was substituted for mCherry–STIM1 in some experiments as indicated in the legends. Cells were used for imaging or electrophysiology 24–48 h after transfection.

Microscopy and imaging methods

Transiently transfected HEK293 cells were plated on to poly d-lysine-coated coverslip chambers and imaged on an IX71 inverted microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA) equipped with a 60× oil immersion objective (Olympus), a 175 W xenon arc lamp (Sutter, Novatao, CA, USA), and excitation and emission filter wheels (Sutter). Images were captured on a cooled CCD camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ, USA). CFP, YFP and FRET fluorescence was visualized with the following filter cubes (Chroma Technology): CFP: 440 ± 20 nm excitation, 455DCLP dichroic, 485 ± 40 nm emission; YFP: 500 ± 20 nm excitation, Q515LP dichroic, 535 ± 30 nm emission; FRET: 440 ± 20 nm excitation, 455DCLP dichroic, 535 ± 30 nm emission. Image acquisition was performed with IPLab software (Scanalytics, Rockville, MD, USA). Time-lapse experiments monitoring dynamic FRET changes following store depletion with TG were acquired at 12 s frame interval. The experiments described in Fig. 2 using ionomycin were acquired at 3 s frame interval. Images were captured at an exposure of 200 ms with 1 × 1 binning. Lamp output was attenuated to 25% by a 0.6 ND filter in the light path to minimize photobleaching. Under these conditions, experiments with cells expressing Orai1–CFP and Orai1–YFP revealed that fluorescence intensity slightly decreased over 600 s due to photobleaching, resulting in an increase in FRET efficiency by ∼3% (n = 5 cells). Given the relatively small amplitude and the slow, uniform kinetics of this effect, we did not correct the images for photobleaching in our analysis. All experiments were performed at room temperature.

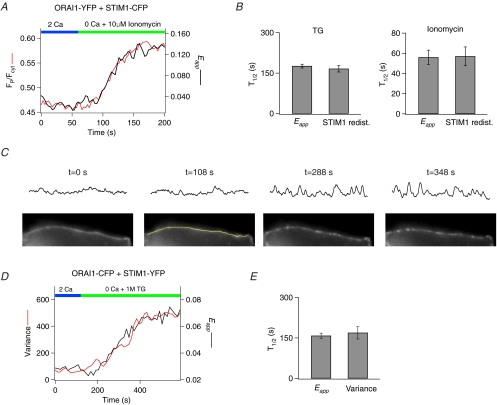

Figure 2. Orai1–STIM1 FRET occurs in close correspondence with STIM1 redistribution and the formation of Orai1 puncta.

A, comparison of the time course of STIM1 redistribution and increase in Orai1–STIM1 FRET. A HEK293 cell expressing STIM1–CFP and Orai1–YFP was treated with 10 μm ionomycin to deplete Ca2+ stores and imaged in a time-lapse experiment. Redistribution of STIM1–CFP from the bulk ER to the PM was quantified as the ratio (FP/Fcyt) of the mean CFP fluorescence at the PM to the mean CFP fluorescence in the cytoplasmic region excluding the PM (Supplementary Fig. 3A). B, summary of the half-times of the increase in Eapp and STIM1 redistribution triggered by store depletion with 1 μm TG (n = 5 cells) or 10 μm ionomycin (n = 5 cells). C, method employed for quantification of Orai1 puncta formation. The lower panels show time-lapse images of a cell expressing Orai1–CFP. The application of TG at 120 s causes Orai1–CFP to gradually redistribute into discrete puncta. The upper panels show the CFP intensity profiles of lines drawn over the PM (an example line is illustrated in the image at 108 s). The Orai1–CFP profile was used for defining the PM. Formation of Orai1 puncta results in the appearance of peaks and troughs on the intensity plot, causing an increase in variance of the overall intensity plot profile. D, comparison of the time course of changes in the variance of the Orai1–CFP plot profile with the Orai1–STIM1 Eapp following store depletion in a single cell. E, summary of the half-times of Orai1–STIM1 Eapp increase and Orai1 puncta formation (n = 4 cells).

Image analysis

Image analysis was performed with NIH ImageJ software. All images were corrected for background fluorescence measured from untransfected cells. A manual threshold was applied to the CFP image (for STIM–Orai1 FRET analysis) or the YFP image (for Orai1–Orai1 FRET analysis) to generate a binary mask that was then employed to restrict further analysis to pixels within the mask. FRET measurements using the 3-cube method were carried from the sensitized emission of the acceptor to collect CFP, YFP and FRET images under stationary conditions (see Zal & Gascoigne, 2004 for detailed description of FRET methods). The FRET image contains bleed-through contamination by directly excited fluorescence of the acceptor and by the tail of the donor emission into the acceptor channel. The bleed-through components are removed by linear unmixing to generate a corrected FRET image (Fc) according to the equation:

| (1) |

where IDA, IDD and IAA are the background-subtracted FRET, CFP and YFP images, respectively. The microscope-specific bleed-through constants a and d were determined by examining bleed-through from cells expressing cytosolic CFP or YFP alone. These were a = 0.04 ± 0.001 (n = 16 cells) and d = 0.41 ± 0.006 (n = 14 cells). The apparent FRET efficiency of the sample was then calculated from the relationship (Zal & Gascoigne, 2004):

| (2) |

where Eapp is the fraction of CFP exhibiting FRET and G is a microscope specific constant derived by measuring CFP fluorescence increase after YFP acceptor photobleaching using an intramolecular CFP–YFP construct. We used YC4.2 cameleon for determination of G, which was measured to be 2.7 ± 0.2 (n = 24 cells). Equation (2) does not yield a ‘true’ FRET efficiency E (a measure of distance and orientation) but instead the product of E and the fractional occupancy of the donor as defined by the relationship (Hoppe et al. 2002; Zal & Gascoigne, 2004; Wlodarczyk et al. 2008):

| (3) |

where FD is the fraction of donor in complex with acceptor. For a bimolecular reaction involving complex formation between two interacting proteins with attached labels, FD is given by (Wlodarczyk et al. 2008):

| (4) |

A manual threshold was applied on the final Eapp image to restrict Eapp values between 0 and 1.0 to prevent errors arising from a few pixels (usually < 5%) that were outside this range. All 3-cube quantification was done in a region of interest (ROI) that only included the plasma membrane (as assessed from the Orai1 image) to restrict the analyses to the peripheral region of the cell where FRET interactions are predicted to occur.

In a second method employed for time-lapse experiments in which dynamic changes in FRET were tracked in response to store depletion, a simplified 2-cube approach was used (Gordon et al. 1998; Wlodarczyk et al. 2008) to collect CFP and FRET images. The FRET image was then corrected for bleed-through from the CFP channel alone. The 2-cube method was applied to simplify the image collection and analysis of the FRET indices. In this case, the Fc image was derived from the relationship:

| (5) |

Eapp was calculated as before from eqn (2). To determine whether the 2-cube simplification results in false positive FRET changes in the time-lapse experiments, we compared in the same cells, Eapp values determined with this method to those derived from the 3-cube method from images collected before and after time-lapse runs (Supplementary Fig. 1). This analysis indicated that the absolute values of Eapp reported by the 2-cube approach were slightly higher than those derived from 3-cube measurements (Supplementary Fig. 1), as expected from a larger Fc term in the numerator of eqn (2) due to bleed-through from the YFP channel. However, overall Eapp values between the two methods were very well correlated (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that 2-cube measurements are valid for tracking dynamic, temporal changes in the concentration of FRET complexes, in agreement with the analysis of Gordon et al. (1998) and Wlodarczyk et al. (2008). Therefore, in this study we employed the 2-cube method to track dynamic changes in FRET in time-lapse experiments, and used the 3-cube method for quantification of FRET changes from steady-state images collected before and after treatments.

Solutions and chemicals

The standard extracellular Ringer solution contained (mm): 150 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 d-glucose and 5 Na-Hepes (pH 7.4). In Ca2+-free Ringer solution, 1 mm EGTA + 2 mm MgCl2 was substituted for CaCl2. For measurements of ICRAC in patch-clamp recordings, 20 mm CaCl2 was employed. DVF Ringer solution contained (mm): 150 NaCl, 10 HEDTA, 1 EDTA and 10 Hepes (pH 7.4). The internal solution for recording ICRAC contained (mm): 135 caesium aspartate, 8 mm MgCl2, 8 BAPTA and 10 Cs-Hepes (pH 7.2). Stock solutions of thapsigargin and 2-APB (Sigma) were dissolved in DMSO and diluted to the indicated concentrations prior to the experiment.

Patch-clamp measurements

Patch-clamp recordings were performed at room temperature using standard methods as previously described (Yamashita et al. 2007). Currents were filtered at 1 kHz with a 4-pole Bessel filter and sampled at 5 kHz. CRAC currents were measured using a voltage protocol consisting of a 100 ms step to −100 mV followed by a ramp from −100 to +100 mV lasting 100 ms. Voltage pulses were delivered at 1 s intervals from a holding potential of +30 mV.

Results

Detection of STIM1–Orai1 association with FRET microscopy

STIM1 and Orai1 redistribute from diffuse localization in resting cells into discrete puncta at the ER–PM junctions following store depletion. To examine whether accumulation of STIM1 and Orai1 at the ER–PM junctions brings these proteins within sufficient proximity to permit their direct binding, we constructed the STIM1–CFP and Orai1–YFP fusion proteins to use a FRET-based approach to monitor molecular associations of these proteins. Electrophysiological experiments indicated that the co-expression of STIM1–YFP and Orai1–CFP into HEK293 cells produced large inward currents following store depletion (Supplementary Fig. 2). The properties of this current were consistent with ICRAC based on several criteria, including an inwardly rectifying current–voltage relationship, characteristic depotentiation in divalent-free solution, slow repotentiation following the readdition of extracellular Ca2+, and low permeability to Cs+, indicating that the attachment of fluorophores does not grossly interfere with the proper localization and functional properties of STIM1 and Orai1.

Store depletion with 1 μm thapsigargin (TG) resulted in redistribution of STIM1–YFP to the cell periphery where it co-clustered with Orai1–CFP in discrete puncta (Fig. 1A). This was accompanied by striking increases in the apparent FRET efficiency (Eapp) between STIM1–YFP and Orai1–CFP (Fig. 1A). Several tests confirmed that the store depletion-induced increase in FRET was due to a specific increase in energy transfer, and therefore, increased association between STIM1 and Orai1. First, YFP photobleaching in store-depleted cells increased the fluorescence of CFP, consistent with an increase in the energy transfer between the donor/acceptor fluorophores (data not shown). Second, refilling of ER Ca2+ stores following washout of the reversible SERCA pump inhibitor CPA decreased STIM1–Orai1 FRET (Fig. 1B) and also reversed STIM1–Orai1 puncta (data not shown). Additionally, the FRET increase stimulated by store depletion was abolished by a mutation in the EF-hand domain of STIM1 (D76ASTIM1–YFP), which diminishes the ability of STIM1 to bind Ca2+ (Fig. 1C). This mutation results in the formation of STIM1 puncta and the constitutive activation of ICRAC even without store depletion (Liou et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2005). The basal Eapp in cells transfected with D76ASTIM1–YFP was higher compared to resting as well as store-depleted WT STIM1–YFP-expressing cells (Fig. 1D), probably because a greater fraction of D76ASTIM1 is localized at the junctional ER sites than WT STIM1, resulting in a higher fraction of CFP in complex with YFP (eqn (4)). Together with the reversal of STIM–Orai1 FRET by washout of CPA described above, this finding suggests that store depletion-induced changes in STIM1–Orai1 FRET are controlled by the dissociation/association of Ca2+ from the luminal EF-hand domain of STIM1.

Figure 1. Store depletion results in FRET between Orai1–CFP and STIM1–YFP.

A, HEK293 cells expressing Orai1–CFP and STIM1–YFP were imaged in 2 mm Ca2+ (pre-TG) and 300 s following the addition of 1 μm TG in Ca2+-free Ringer solution (post-TG). TG-induced store depletion alters the distribution of STIM1–YFP and Orai1–CFP from diffuse expression to overlapping puncta at the cell periphery. This is accompanied by increase in FRET. The graph on the right plots the time course of Eapp between Orai1–CFP and STIM1–YFP in a different cell following depletion of Ca2+ stores. B, the increase in FRET between Orai1–CFP and STIM1–YFP triggered by store depletion is reversed by washout of the reversible SERCA-pump inhibitor, CPA. Trace shows Eapp in a single HEK293 cell and is representative of 5/5 experiments. A Ringer solution containing a high concentration of extracellular Ca2+ (20 mm) was employed to facilitate store refilling following washout of CPA. C, an EF-hand STIM1 mutation, D76ASTIM1, abolishes the FRET change with store depletion. The trace shows a Eapp measurement in a single cell expressing D76ASTIM1–YFP + Orai1–CFP. D, summary of 3-cube Eapp values in cells expressing WT STIM1–YFP and Orai1–CFP (n = 64 cells) at rest and 300 s after store depletion with 1 μm TG, and in cells expressing D76ASTIM1–YFP (n = 9 cells) at rest.

Association of STIM1 and Orai1 occurs in parallel with STIM1 and Orai1 redistribution

If the increase in STIM1–Orai1 FRET described above reflects specific interactions between STIM1 and Orai1 at the ER–PM junctions, then the kinetics of the FRET increase should closely follow their redistribution and accumulation at the peripheral sites. Because store depletion redistributes STIM1 from the bulk ER to the plasma membrane, it is possible to quantify STIM1 redistribution as the ratio of the STIM1–CFP fluorescence in the most peripheral region of the cell (FP) to the fluorescence in an adjacent intracellular region (Fint) (Luik et al. 2008; Supplementary Fig. 3A). This analysis did not reveal any difference between the onset or the overall time course of the rise in the FRET signal and the redistribution of STIM1 in the same cells, both under conditions of slow store depletion with TG and during rapid store depletion with 10 μm ionomycin (Fig. 2A and B). Thus, the interaction of STIM1 with Orai1 occurs in close correspondence with the redistribution of STIM1 to the PM.

We also compared the time course of the STIM1–Orai1 FRET increase with the redistribution of Orai1 following store depletion in the same cells. To quantify the kinetics of the reorganization of Orai1–CFP into discrete puncta, the variance of Orai1–CFP at the cell periphery was measured for each frame of a time-lapse experiment. In resting cells with full stores, the expression of Orai1–CFP in the PM is largely homogenous, yielding a relatively low variance of CFP intensity on lines drawn along the cell membrane (Fig. 2C). Since store depletion results in the reorganization and accumulation of Orai1 into discrete puncta, plots of Orai1–CFP intensity at the PM yield peaks and troughs (Fig. 2C). We compared the timing of the increase in Orai1–CFP variance to that of the increase in Eapp following store depletion in the same cells. This analysis indicated that the increase in FRET occurred in close correspondence with the enhancement of the Orai1–CFP variance (Fig. 2D and E). Together with the close coupling of the FRET signal with the redistribution of STIM1 noted in the preceding section, these results establish that store depletion triggers coordinated redistributions of STIM1 and Orai1 in the ER and plasma membranes, respectively, bringing them within sufficiently close proximity to permit FRET to occur.

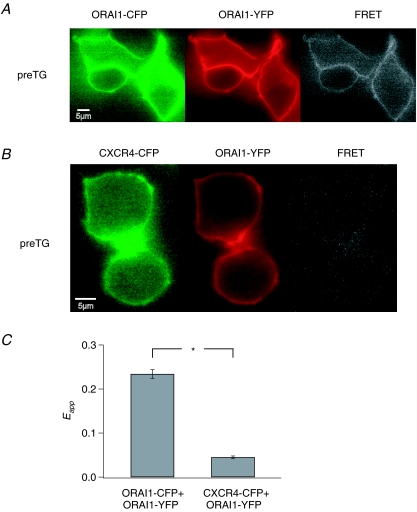

Orai1 exists in a multimerized state at rest

The ability of FRET to report the association of STIM1 and Orai1 in live cells led us to consider whether this approach could be employed to detect the assembly of Orai1 subunits into functional CRAC channels. Recent reports have indicated that CRAC channels are assembled from multiple Orai1 subunits, and a tetrameric Orai1 stochiometry has been proposed (Vig et al. 2006; Gwack et al. 2007; Mignen et al. 2008). To test for FRET between adjacent subunits of the CRAC channel, we co-expressed Orai1–YFP and Orai1–CFP at a 1: 1 mixture of cDNA together with mCherry–STIM1 (Fig. 3A). This resulted in robust constitutive FRET between CFP and YFP in resting cells (Fig. 3A). Photobleaching of YFP resulted in a significant increase in CFP fluorescence, consistent with energy transfer between the donor and acceptor (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Substituting unlabelled STIM1 for mCherry–STIM1 did not affect the Eapp measurements, indicating that the presence of mCherry in the luminal N-terminus of STIM1 does not influence Orai1–Orai1 FRET (data not shown).

Figure 3. Multimeric assembly of Orai1 subunits detected by FRET.

A, HEK293 cells expressing Orai1–CFP and Orai1–YFP exhibit a high level of resting FRET in the absence of store depletion. Images were taken in 2 mm Ca2+. B, over-expression of Orai1–YFP together with an unrelated YFP-labelled plasma membrane protein, CXCR4-CFP, results in significantly lower FRET. C, summary of mean ±s.e.m. 3-cube Eapp in HEK293 cells expressing Orai1–YFP and Orai1–CFP (n = 85 cells) and in cells expressing CXCR4-CFP and Orai1–YFP (n = 48 cells).

To confirm that the observed Orai1–Orai1 FRET is not simply due to close packing of neighbouring channels containing CFP- and YFP-attached subunits, we measured FRET arising from the co-expression of Orai1–YFP with an unrelated plasma membrane protein (CFP-labelled chemokine receptor, CXCR4). Although both Orai1–YFP and CXCR4–CFP were robustly expressed in the plasma membrane, Eapp measurements revealed very little FRET (Fig. 3B and C), indicating that non-specific FRET between neighbouring channels does not appreciably occur under our experimental conditions. Collectively, these results indicate that Orai1 multimerizes with itself and confirm previous conclusions (Vig et al. 2006; Gwack et al. 2007; Mignen et al. 2008) regarding the multimeric nature of the CRAC channel.

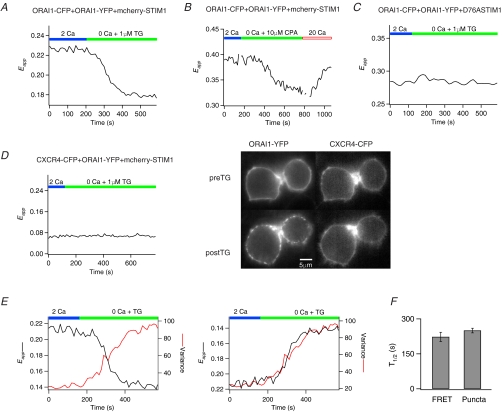

Orai1–Orai1 FRET declines with store depletion

Given that the redistribution of STIM1 and Orai1 following store depletion brings these proteins sufficiently close to permit binding interactions to occur, what molecular changes does this trigger in the CRAC channel? We examined this by testing whether store depletion alters Orai1–Orai1 FRET. Unexpectedly, store depletion caused a decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET (Fig. 4A). 3-Cube FRET measurements indicated that treatment with TG decreased Eapp from 0.23 ± 0.01 to 0.20 ± 0.01 (P << 0.001), a decline of 13 ± 0.6% (n = 85 cells). Several lines of evidence indicated that the drop in Orai1–Orai1 FRET is associated with store-dependent activation of CRAC channels and is not a non-specific effect of fluorophore quenching, photo-conversion or other factors. First, the Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline was also seen when unlabelled STIM1 was used instead of mCherry–STIM1 (e.g. Fig. 4E), indicating that it is not simply due to additional FRET interactions between Orai1–YFP and mCherry–STIM1. Second, washout of the reversible SERCA pump inhibitor, CPA, reversed the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET (Fig. 4B). Given that washout of CPA reverses the association of STIM1 and Orai1 (Fig. 1B), this result suggests that Orai1 FRET decline is directly related to the Ca2+ filling state of the ER. Third, co-expression with the EF-hand STIM1 mutant, D76ASTIM1, abolished the store-dependent decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET (Fig. 4C), presumably because of the constitutive association of D76ASTIM1 with Orai1. Finally, the decline was Orai1 specific: cells over-expressing STIM1 and Orai1–YFP and CXCR4–CFP failed to exhibit changes in FRET following store depletion despite obvious Orai1–CFP puncta formation (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Store depletion triggers a decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET.

A, a HEK293 cell expressing Orai1–CFP, Orai1–YFP and mcherry–STIM1 was treated with 1 μm TG to deplete stores. All traces illustrate Eapp measurements in single cells. B, the decrease in Orai1–Orai1 FRET triggered by store depletion is reversed by washout of the reversible SERCA-pump inhibitor, CPA, with 20 mm[Ca2+]o. This cell had significantly higher YFP expression than the cell shown in A, resulting in a higher resting 2-cube Eapp. C, HEK293 cells expressing the EF-hand STIM1 mutant, D76ASTIM1, together with Orai1–CFP and Orai1–YFP fail to exhibit the drop in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion. D, the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion is absent in cells over-expressing Orai1–YFP and the unrelated membrane protein CXCR4-CFP. Orai1–YFP exhibited its characteristic redistribution upon store depletion. The cells shown here are the same as in Fig. 3B. E, comparison of the time course of the decline in Orai1–Orai1 Eapp and the increase in Orai1–CFP variance at the plasma membrane in a single cell using the method described in Fig. 2. The Orai1–Orai1 Eapp decline was inverted in the right panel to directly compare the kinetics of the two processes. Unlabelled STIM1 was used in these experiments. F, summary of the half-times of the Orai1–Orai1 Eapp changes and the formation of Orai1 puncta (n = 4 cells).

To further characterize the relationship between the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET and the reorganization of Orai1 following store depletion, we compared the time course of the FRET decline and Orai1 puncta formation. If the decline in FRET described above reflects a step in the activation of CRAC channels, then the kinetics of the FRET decline should be related to the redistribution and accumulation of Orai1 at the peripheral sites. By contrast, the relative timing of the two processes would be independent if they were unrelated. Measurements of the time course of the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET and Orai1 puncta formation following store depletion with TG in the same cells indicated that the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET occurred in parallel with the formation of Orai1 puncta (Fig. 4E and F). Collectively, these results indicate that the interaction of STIM1 and Orai1 following store depletion is associated with rearrangements in the multimeric Orai1 complex, seen here as a drop in Orai1–Orai1 FRET.

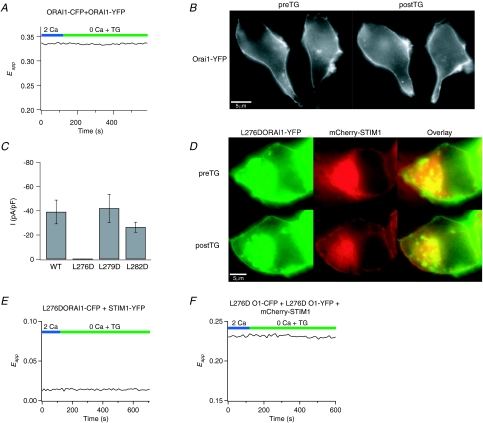

The Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline was only observed when STIM1 was co-transfected with Orai1. In the absence of STIM1 co-expression, neither the reorganization of Orai1 into puncta following store depletion nor the Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline was seen (Fig. 5A and B), suggesting that the decrease in Orai1–Orai1 FRET requires STIM1–Orai1 interaction. As a further test of this idea, we examined whether mutations in Orai1 that disrupt the interaction of STIM1 and Orai1 also interfere with the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET. A recent study has implicated a hydrophobic domain in the C-terminus of Orai1 for the interaction of STIM1 with Orai1, and L273 has been identified as a critical residue (Muik et al. 2008). To uncover the contributions of this region for the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET, we generated several additional mutations of hydrophobic amino acid residues. Some mutations, such as the triple mutant, L276D,F279D,L282D Orai1 resulted in aberrant Orai1 expression in an unknown intracellular compartment and were not studied further (Supplementary Fig. 4A). However, the L276D, F279D and L282D Orai1 single mutations showed robust plasma membrane expression with L276D Orai1 exhibiting additional intracellular expression in some cells (e.g. Fig. 5D). Examination of the F279 and L282D Orai1 mutations revealed that store depletion triggered their redistribution into discrete puncta, and FRET measurements revealed robust increases in STIM1–Orai1 FRET (Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, patch-clamp recordings indicated that F279D and L282D Orai1 produced large Ca2+ currents with properties consistent with those of ICRAC (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, the F279D and L282D Orai1 mutations do not affect the ability of STIM1 to interact with Orai1 or the overall channel activation process.

Figure 5. The decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET requires the interaction between STIM1 and Orai1.

A and B, in the absence of STIM1 co-expression, the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET (A) and the formation of Orai1 puncta following store depletion (B) is abolished. Eapp was measured as described before in a HEK293 cell transfected with Orai1–CFP and Orai1–YFP (but no STIM1). The images in B were collected in 2 mm Ca2+ (preTG) in resting cells and 300 s following treatment with 1 μm TG in Ca2+-free Ringer solution (postTG). C, a mutation in the C-terminus of Orai1 (L276D) abolishes ICRAC. Currents arising from WT or mutant Orai1 co-expressed with unlabelled STIM1 in HEK293 cells were recorded in 20 mm[Ca2+]o solution following store depletion with 1 μm TG. Each point shows mean ±s.e.m. from 5 to 8 cells. D, L276D Orai1 fails to reorganize into puncta following store depletion. Images were acquired at rest and 300 s following exposure to 1 μm TG. Note the significant expression of Orai1 in an intracellular compartment. Although store depletion redistributes STIM1–YFP into puncta at the cell periphery, the plasma membrane fraction of Orai1–CFP does not form puncta. E, the L276D Orai1 mutation abolishes increases in FRET between STIM1 and Orai1. The trace shows STIM1–Orai1 FRET in a HEK293 cell expressing L276D Orai1–CFP and STIM1–YFP. Similar results were observed in 11/11 cells. F, the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion is abolished by L276D mutation. The trace shows Orai11–Orai1 Eapp in a single HEK293 cell expressing L276D Orai1–CFP, L276D Orai1–YFP and mCherry–STIM1. Similar results were observed in 10/10 cells.

By contrast, patch-clamp recordings indicated that the L276D Orai1 mutation fails to produce functional CRAC currents (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. 5). In cells expressing this Orai1 mutant, depletion of Ca2+ stores triggered the reorganization of STIM1 and its accumulation at the cell periphery (Fig. 5D). However, the redistribution of Orai1 into discrete puncta (Fig. 5D) and increases in STIM1–Orai1 FRET failed to occur (Fig. 5E), indicating that the L276D Orai1 mutation results in impaired interaction with STIM1. Importantly, the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET also did not occur in this case (Fig. 5F), indicating that disruption of the STIM1–Orai1 interaction interferes with the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET. Thus, together with the lack of decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET in the absence of STIM1 co-expression noted above, this result argues that the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET is dependent on and occurs downstream of the interaction of STIM1 with Orai1.

The decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET with store depletion arises from molecular rearrangements within the CRAC channel

What specific change does the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion represent? We considered two possibilities. First, because Orai1 redistributes in the plasma membrane, changes in FRET could in principle, arise from changes in the degree of non-specific coupling due to close packing of neighbouring CRAC channels. A second possibility is that it reflects molecular rearrangements of the C-terminal domains of Orai1.

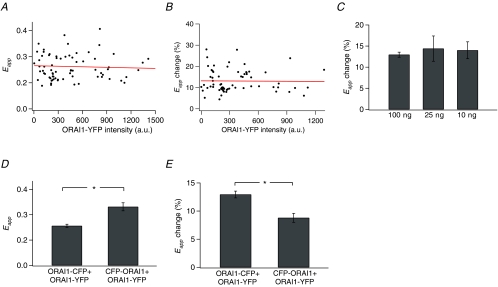

Non-specific FRET occurs from random, collision-driven interactions between donors and acceptors in the plasma membrane and depends on the concentrations of the donors and acceptors in the membrane (Zal & Gascoigne, 2004). Plots of the resting Eapp against Orai1–YFP intensity did not reveal any dependence, indicating that non-specific FRET does not significantly contribute to the resting Orai1–Orai1 FRET (Fig. 6A). Likewise, the change in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion was independent of the Orai1–YFP intensity or the specific amount of cDNA introduced (Fig. 6B and C). Thus, these results argue that the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion is not simply due to changes in the levels of non-specific FRET between neighbouring channels.

Figure 6. The drop in Orai1–Orai1 FRET is independent of expression levels of Orai1 but depends on the position of the fluorophores.

A, resting Eapp values plotted against the intensity of Orai1–YFP in 83 cells. Cells were transfected with Orai1–YFP, Orai1–CFP, at 10, 25 or 100 ng per coverslip together with mCherry–STIM1 and Eapp was measured prior to store depletion in 2 mm Ca2+ Ringer solution. B, the decline in Eapp following store depletion is independent of the expression of Orai1–YFP. Eapp was measured 300 s following the addition of 1 μm TG in Ca2+-free Ringer solution in cells transfected with Orai1–YFP/Orai1–CFP at 100 ng per coverslip (n = 69 cells). C, altering the amount of Orai1 DNA does not change the extent of decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion. HEK293 cells were transfected with Orai1–YFP/Orai1–CFP DNA at the indicated amounts per fluorophore. D, altering the position of CFP from C- to the N-terminus of Orai1 results in enhanced resting FRET (P < 0.001). Resting 3-cube Eapp values in cells transfected with either Orai1–CFP and Orai1–YFP (both C-terminally tagged; n = 83 cells) or CFP–Orai1 (N-terminally tagged) and Orai1–YFP (C-terminally tagged; n = 34 cells) in 2 mm Ca2+. E, the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion is reduced in cells expressing CFP–Orai1 + Orai1–YFP (P < 0.001).

To test the alternate idea that the Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline arises from molecular rearrangements of the C-terminal domains within the CRAC channel complex, we examined whether the location of the fluorescent tag (N versus C) influences the Orai1–Orai1 FRET signal and its decline following store depletion. Moving CFP to the N-terminus (CFP–Orai1) significantly increased the degree of resting FRET (Fig. 6D). Although store depletion resulted in a decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET, its extent was significantly lower when CFP was at the N-terminus (Fig. 6E). Thus, the degree of FRET and its change following store depletion is dependent on the position of the fluorescent tag, strongly suggesting that the decline arises from physical rearrangements within the CRAC channel.

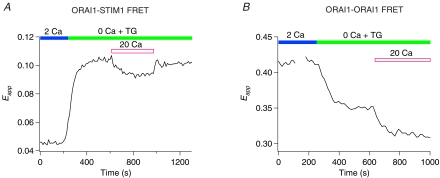

As a further test of the idea that the Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline arises from molecular rearrangements in the CRAC channel, we examined whether manipulations that enhance CRAC channel activity also change the FRET signal. A powerful modulator of CRAC channel activity is extracellular Ca2+. Extracellular Ca2+ at millimolar concentrations strongly enhances CRAC channel activity by a process termed calcium-dependent potentiation (CDP). Conversely, the removal of extracellular Ca2+ by perfusing divalent-free (DVF) solutions diminishes CRAC channel activity over tens of seconds due to the reversal of CDP or depotentiation (e.g. Supplementary Fig. 2) (Lepple-Wienhues & Cahalan, 1996; Prakriya & Lewis, 2002; Su et al. 2004). Could these alterations in the functional state of the CRAC channel arise from changes in STIM1–Orai1 interactions and/or conformational changes in Orai1? We tested this by examining whether extracellular Ca2+ alters STIM1–Orai1 and Orai1–Orai1 FRET interactions. Exposing cells to 20 mm[Ca2+]o following store depletion slightly diminished STIM1–Orai1 FRET (Fig. 7A). Partial refilling of the Ca2+ store was probably responsible for this effect since measurements of [Ca2+]ER using an ER-targeted Ca2+ indicator (ER-cameleon) revealed small increases in [Ca2+]ER following the addition of 20 mm Ca2+ in TG-pre-treated cells (data not shown). Importantly, examination of Orai1–Orai1 FRET revealed that exposing cells to 20 mm[Ca2+]o caused a decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET beyond that elicited by store depletion alone (Fig. 7B) (3-cube Eapp declined by 6 ± 0.5% following a 3 min exposure to 20 mm Ca2+ (n = 18 cells; P < 0.001)). These results indicate that extracellular Ca2+, which increases CRAC channel activity, elicits rearrangements in the CRAC channel that, like store depletion, causes the Orai1–Orai1 FRET signal to decline.

Figure 7. Extracellular Ca2+ partially reverses the association of Orai1 with STIM1 but enhances the store-dependent conformational change in Orai1.

A, alteration of Orai1–STIM1 FRET in response to application of 20 mm[Ca2+]o. Trace shows changes in Eapp in a single HEK293 cell expressing Orai1–CFP and STIM1–YFP. B, the drop in Orai1–Orai1 FRET upon depletion of stores is further enhanced following application of 20 mm[Ca2+]o. Trace shows changes in Eapp in a single HEK293 cell expressing Orai1–CFP and ORA1–YFP together with mCherry–STIM1.

Based on these results as well as the evidence given above that the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET is store dependent and occurs in parallel with Orai1 puncta formation, we conclude that the FRET decline arises from conformational rearrangements of the Orai1 C-terminal domains within the CRAC channel. In the sections that follow, we employed STIM1–Orai1 and Orai1–Orai1 FRET measurements to monitor two key steps in the CRAC channel activation pathway: the association of STIM1 and Orai1 and the conformational rearrangements within the CRAC channel to explore the effects of the compound 2-APB, and a human Orai1 mutation that abolishes channel activity.

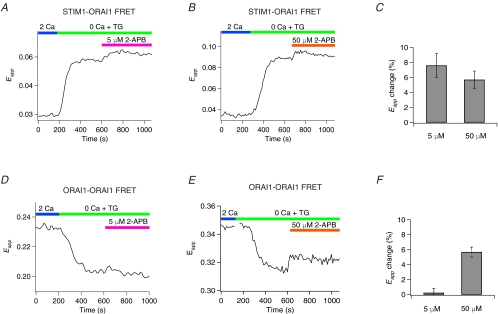

Effects of 2-APB on STIM1–Orai1 and Orai1–Orai1 associations

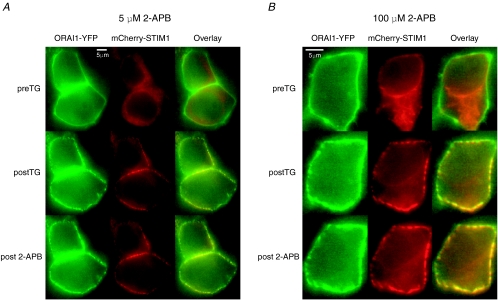

The pharmacological agent 2-APB elicits complex effects on ICRAC including a 2- to 5-fold persistent enhancement of ICRAC at low concentrations (1–10 μm) and transient enhancement followed by strong inhibition at high concentrations (> 20 μm) (Prakriya & Lewis, 2001). The mechanism of 2-APB action on ICRAC remains uncertain, but the complexity of effects elicited by 2-APB suggests that this compound may target multiple processes. Two recent studies have reported that high concentrations of 2-APB disperse STIM1 puncta (Dehaven et al. 2008; Peinelt et al. 2008), raising the possibility that 2-APB inhibition of ICRAC may arise, at least in part, due to disruption of STIM1–Orai1 interaction. To test this possibility, we examined whether 2-APB changes STIM1/Orai1 puncta and STIM1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion.

Neither low (5–10 μm) nor high (50–100 μm) concentrations of 2-APB visibly altered STIM1 and Orai1 puncta in store-depleted cells (Fig. 8). Additionally, pre-exposure to 2-APB (50 μm) prior to store depletion did not qualitatively diminish the ability of TG to subsequently induce puncta formation (data not shown). Thus, under our experimental conditions, 2-APB did not result in gross alteration of the localization of STIM1 and Orai1. By contrast, FRET measurements revealed that low concentrations of 2-APB (5–10 μm) that potentiate CRAC currents resulted in a significant increase in STIM1–Orai1 FRET (Fig. 9A and C). Importantly, this behaviour was not limited just to the low 2-APB concentrations. A higher concentration of 50 μm that is known to transiently potentiate, then inhibit ICRAC, also increased FRET between STIM1 and Orai1 (Fig. 9B and C). Thus, both low and high concentrations of 2-APB enhance STIM1–Orai1 FRET suggesting that one effect of this compound is to enhance the interaction of STIM1 with Orai1.

Figure 8. Orai1 and STIM1 puncta are unaffected by 2-APB.

A, a low concentration of 2-APB (5 μm) does not affect STIM1 and Orai1 puncta following store depletion. Cells were treated with 1 μm TG for 300 s to deplete Ca2+ stores and induce the redistribution and accumulation of STIM1 and Orai1 into discrete puncta. 2-APB (5 μm) was subsequently applied to the store-depleted cells, and images were collected 2 min following the addition of 2-APB. B, a high concentration of 2-APB (100 μm) similarly did not disturb Orai1 or STIM1 puncta resulting from depletion of stores.

Figure 9. 2-APB enhances the association of Orai1 with STIM1 and partially reverses the store-dependent Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline.

A and B, application of 2-APB following store depletion at either 5 μm (A) or 50 μm (B) causes an increase in Orai1–STIM1 FRET. The traces show Eapp changes in single HEK293 cells expressing Orai1–CFP and STIM1–YFP. C, summary of 3-cube Eapp changes induced by 5–10 μm (n = 11 cells) and 50 μm 2-APB (n = 17 cells) following 3 min exposure to 2-APB. D and E, the drop in Orai1–Orai1 Eapp resulting from store depletion with TG is partially reversed after treatment with 50 μm 2-APB. The traces shows Eapp changes in single HEK293 cells expressing Orai1–CFP and Orai1–YFP, and mCherry–STIM1 during store depletion and subsequent treatment with either 5 μm (D) or 50 μm (E) 2-APB. Application of 5 μm 2-APB does not alter Orai1–Orai1 FRET. F, summary of 3-cube Eapp changes induced by 5 μm (n = 10 cells) and 50 μm 2-APB (n = 20 cells) following 3 min exposure to 2-APB.

Next, we examined whether 2-APB directly modulates the Orai1 channel complex by monitoring its effects on Orai1–Orai1 FRET. A low concentration of 2-APB (5 μm), which potentiates but does not inhibit CRAC channels (Prakriya & Lewis, 2001), failed to detectably alter Orai1–Orai1 FRET (Fig. 9D and F). By contrast, application of a high concentration of 2-APB (50 μm) to store depleted cells resulted in an increase in the Orai1–Orai1 FRET signal (Fig. 9E and F). This effect of 2-APB was only seen in store-depleted cells; application of the drug on resting cells did not enhance ORA1–Orai1 FRET (data not shown). Given that the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion is associated with CRAC channel activation, the partial reversal of this process by high concentrations of 2-APB suggests that it may be a manifestation of a specific and direct 2-APB effect on a gating event in the CRAC channel. Collectively, these results indicate that both low and high concentrations of 2-APB enhance the association of STIM1 with Orai1, but only the high concentrations of 2-APB alter subunit interactions in the Orai1 channel complex.

A SCID mutation does not alter STIM1–Orai1 association or conformational changes in Orai1 following store depletion

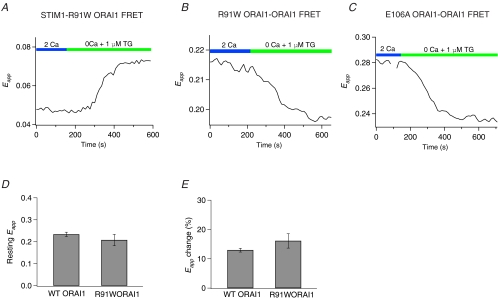

A single missense mutation in Orai1, R91W, eliminates ICRAC and leads to a severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) syndrome in human patients (Feske et al. 2005,2006). The mechanism by which this mutation abolishes CRAC channel function is unknown, but possible explanations could include disruption of the reorganization of Orai1 and/or its association with STIM1 following store depletion, or obstruction of a gating step following the channel's interaction with STIM1. Investigation of these possibilities revealed that the store depletion-induced reorganization of STIM1 and Orai1 and the increases in STIM1–Orai1 FRET were similar in R91W Orai1- and WT Orai1-expressing cells, in agreement with the study of Muik et al. (2008) (2-cube Eapp increased by 51 ± 3% (n = 38) in WT Orai1 versus 42 ± 7% (n = 11) in R91W Orai1; Fig. 10A. Furthermore, the resting levels of Orai1–Orai1 FRET as well as its decline following store depletion were also unchanged (Fig. 10D and E). Thus, the R91W Orai1 mutation does not alter the interaction of STIM1 with Orai1, the assembly of mutant Orai1 subunits, or the subsequent conformational change reported by the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET. We also examined whether an unrelated mutation in the putative selective filter of Orai1, E106A, affects the store-dependent decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET. As with R91W Orai1, E106A Orai1 also did not affect the redistribution of Orai1 into discrete puncta following store depletion (data not shown), nor the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion (Eapp declined by 13 ± 0.6% (n = 85) in WT Orai1 versus 16 ± 3% (n = 9) in E106A Orai1) (Fig. 10C). This result suggests that the mutations in the proposed CRAC channel selectivity filter do not affect the conformational change reflected by the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET.

Figure 10. The Orai1–STIM1 and Orai1–Orai1 FRET changes Orai1 mutants are unaffected by Orai1 mutations that produce non-functional channels.

A, increase in FRET in a HEK293 cell expressing R91WOrai1–CFP and STIM1–YFP triggered by 1 μm TG. This behaviour is indistinguishable from that observed in cells over-expressing WT Orai1. B, decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET in a HEK293 cell expressing R91W Orai1–CFP, R91W Orai1–YFP and mCherry–STIM1 triggered by 1 μm TG. C, the putative pore mutation, E106A, does not affect the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET following store depletion. This cell was transfected with E106A Orai1–YFP, E106A Orai1–CFP, and unlabelled STIM1. D, summary of resting 3-cube Eapp levels in cells expressing WT Orai1 (n = 83 cells) and R91WOrai1 (n = 20 cells). E, summary of the changes in Eapp following store depletion in cells expressing WT Orai1 (n = 74 cells) and R91WOrai1 (n = 20 cells). Store depletion was induced by treating cells with 1 μm TG for 300 s in Ca2+-free Ringer solution.

Discussion

A fall in ER Ca2+ leads to a coordinated series of steps culminating in the opening of CRAC channels. Previous studies have identified several key steps of this process: the oligomerization of STIM1 followed by STIM1 redistribution to peripheral sites, accumulation of STIM1 and Orai1 at the ER–PM junctions, and the opening of store-operated channels (Zhang et al. 2005; Luik et al. 2006,2008; Stathopulos et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2006; Liou et al. 2007). Although considerable progress has been made in understanding the early events of the CRAC channel activation process, how the formation of STIM1 puncta activates CRAC channels is unclear. In this study, we have employed FRET measurements to follow interactions between STIM1 and Orai1 and the association of Orai1 subunits into multimeric CRAC channels. This approach has allowed us to identify a STIM1-dependent conformational change in Orai1 that is involved in CRAC channel activation. With these tools, we investigated the mechanism of CRAC channel modulation by extracellular Ca2+ and by 2-APB, and find that both STIM1–Orai1 interactions as well as Orai1 conformational changes can be independently modulated to control the overall activity of CRAC channels.

Interaction of STIM1–Orai1 following store depletion

The leading candidate models for CRAC channel activation include a diffusible messenger released from depleted stores and direct activation of CRAC channels by physical interactions between the channels and proteins in the ER (Parekh & Putney, 2005).Together with recent evidence showing that STIM1 and Orai1 co-cluster at the cell periphery (Luik et al. 2006; Xu et al. 2006) and that these proteins can be co-immunoprecipitated (Vig et al. 2006; Yeromin et al. 2006), the finding that store depletion increases FRET between STIM1 and Orai1 as first reported by Muik et al. (2008) and shown in our study supports the idea that STIM1 physically interacts with Orai1. Establishing an exact distance between these two proteins from our FRET measurements alone is currently not feasible because of the fact that the measured Eapp values depend not only on the separation of the fluorophores, but also on the degree of STIM1–Orai1 complex formation (eqn (4)), for which we have no independent measure. Nevertheless, given that the Forster radius of CFP–YFP pair is 50 Å, the occurrence of FRET between STIM1–YFP and Orai1–CFP suggests that the two proteins approach within 100 Å or less of each other, a distance small enough to permit a direct physical indirect between these proteins.

Kinetic analysis indicates a close correspondence between the redistribution of STIM1 and the time course of STIM1–Orai1 FRET under conditions of both rapid as well as slow store depletion (Fig. 2). The formation of Orai1 puncta also occurs in parallel, suggesting that the association of STIM1 and Orai1 and the formation of Orai1 puncta are constrained mainly by the rate of redistribution and arrival of STIM1 at the junctional ER sites. A dependence on STIM1 is also supported by observations showing that Orai1 fails to form puncta in the absence of STIM1 co-expression or when the STIM1–Orai1 interaction is disrupted as seen with the L276D Orai1 mutation (Fig. 5). Collectively, these results directly demonstrate that the redistributions of STIM1 and Orai1 occur in close temporal correspondence with their mutual interaction.

Changes in Orai1–Orai1 FRET: conformational rearrangements in the CRAC channel

Co-clustering of STIM1 and Orai1 at the ER–PM junctions should lead to conformational changes in the Orai1 subunits culminating in channel opening, but the identity and nature of these steps have never been described. Here, we find that store depletion produces a decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET. Several lines of evidence suggest that this is due to molecular rearrangements in the Orai1 subunits of the CRAC channel. First, the Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline is not simply due to changes in the levels of non-specific FRET between neighbouring channels because there was no correlation between the decline in FRET and Orai1 expression. Second, the location of the fluorescent tag (C- versus N-terminus) influenced both the degree of resting FRET as well as its decline following store depletion. The higher level of resting FRET seen with N-terminally tagged CFP–Orai1 and C-terminally tagged Orai1–YFP also suggests that the N- and C-termini may be in close proximity to each other in the native configuration, which is consistent with the recent observation that concatenated Orai1 subunits linked by short peptides between the N- and C-termini form functional CRAC channels (Mignen et al. 2008). Third, manipulations that are known to enhance or decrease CRAC channel activity (such as extracellular Ca2+ or high concentrations of 2-APB) also enhanced or partially reversed the changes in Orai1–Orai1 FRET. Fourth, the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET requires interaction of Orai1 and STIM1. In the absence of STIM1 co-expression, or when the interaction of Orai1 and STIM1 is disrupted as seen with the L276D Orai1 mutation, the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET is also abolished. Finally, a STIM1 EF-hand mutant (D76ASTIM1) that results in the constitutive activation of CRAC channels also abolishes the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET upon store depletion, in this case due to the constitutive interaction of STIM1 with Orai1. Collectively, these results support the notion that the decline in FRET represents molecular rearrangements within the Orai1 calcium channel following its interaction with STIM1.

At present, we do not know the structural basis for the Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline. If, as proposed (Li et al. 2007; Muik et al. 2008), the C-terminus of Orai1 is the interaction site for STIM1, it seems possible that the engagement of STIM1 to this site may either displace the C-terminus or change the orientation of the nearby fluorophore molecules thereby producing the FRET decline. An alterative possibility is that it represents a gating step in the process of CRAC channel activation. Although our data do not directly distinguish between these possibilities, we believe that the Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline does not merely reflect the displacement of nearby probe molecules due to STIM1 binding, because, if this were the case, manipulations promoting STIM1–Orai1 interaction would also be expected to promote the decline in Orai1–Orai1 FRET. In contrast to this prediction, as illustrated by the effects of 20 mm extracellular Ca2+ and 2-APB (Figs 7 and 9), changes in STIM1–Orai1 FRET are not always well correlated with changes in Orai1–Orai1 FRET. For example, whereas the application of a 20 mm[Ca2+]o solution slightly diminishes the overall STIM1–Orai1 FRET signal (Fig. 7A), probably due to partial store refilling in the continuous presence of a high extracellular Ca2+ solution, it potentiates the Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline, a result that is contrary to predictions from the probe-displacement model. Similarly, no change in Orai1–Orai1 FRET is seen following application of a low concentration of 2-APB despite enhancement of STIM1–Orai1 FRET. Moreover, high drug concentrations partially reverse the Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline seen with store depletion, despite increases in STIM1–Orai1 FRET. Based on these findings, we favour the idea that the Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline represents conformational rearrangements within Orai1 subunits prior to CRAC channel activation. That both store depletion and extracellular Ca2+ cause Orai1–Orai1 FRET to decline suggests that there are common gating steps in the process by which store depletion and CDP increase channel activity.

The Orai1–Orai1 FRET decline is unaffected by the Orai1 pore mutation E106A, which abolishes channel activity (Prakriya et al. 2006). This finding indicates that the Orai1 conformational rearrangement alone is not sufficient to confer ion conduction through Orai1 channels but also requires an intact pore to permit permeation. The human SCID mutation in Orai1, R91W, has a similar phenotype, raising the possibility that the SCID mutation produces a defect in permeation rather than channel gating. Additional studies are needed to understand the full significance and mechanism of the Orai1 FRET decline, and resolution of the structure of Orai1 should greatly facilitate our understanding of this process. Nevertheless, the ability of FRET to detect Orai1 conformational changes suggests that this approach might prove useful in understanding the physical rearrangements within the CRAC channel during channel gating.

2-APB modulates the interaction of STIM1 with Orai1 and alters Orai1 gating

Since the initial discovery that 2-APB potentiates CRAC channels at low concentrations and transiently potentiates, then inhibits at high concentrations, very little insight has emerged on the mechanisms by which 2-APB exerts these effects, in large part due to the lack of identified proteins in the SOC pathway. The discoveries of Orai1 and STIM1 have prompted direct experiments to understand the molecular mechanism of 2-APB modulation in the hope that the information gained from these studies would lead to a fuller understanding of the mechanisms by which CRAC channels are regulated. Here, we find that both low as well as high concentrations of 2-APB increase STIM1–Orai1 FRET. 2-APB did not visibly increase puncta formation or the redistribution of STIM1 and Orai1 (Fig. 8), suggesting that the 2-APB-induced increases in STIM1–Orai1 FRET may arise due to strengthening of existing STIM1–Orai1 contacts rather than recruitment of new contacts. In contrast to the effects on STIM1–Orai1 FRET, however, only high concentrations of 2-APB interfere with the conformational rearrangements in Orai1, as evidenced by the increases in Orai1–Orai1 FRET (Fig. 9E). The absolute changes in Eapp triggered by 2-APB (and extracellular Ca2+) are relatively small (< 10%). However, large changes in channel activity could arise from relatively small conformational changes within channel proteins. Based on these findings, we propose that 2-APB-induced potentiation of ICRAC occurs, at least in part, due to enhanced STIM1–Orai1 interaction, whereas inhibition of ICRAC, which is specific to high drug concentrations, arises from alteration of CRAC channel gating. A direct effect on channel gating by high concentrations of 2-APB is also supported by electrophysiological measurements of ICRAC, which reveal that the 2-APB-induced current inhibition is accompanied by the loss of fast Ca2+-dependent inactivation (Prakriya & Lewis, 2001), a gating process probably mediated by conformational changes in the channel.

Our conclusion that 2-APB inhibition arises from a direct alteration of CRAC channel gating differs from the conclusions of two recent studies (Dehaven et al. 2008; Peinelt et al. 2008). These studies attributed 2-APB inhibition of ICRAC, in part, to the ability of this compound to reverse STIM1 puncta, and therefore, presumably to the disruption of STIM1–Orai1 interactions. The discrepancy with our conclusions may be explained by the fact that our experiments were performed in HEK293 cells transfected with both STIM1 and Orai1, whereas the powerful reversal of STIM1 puncta was reported in cells over-expressing STIM1 alone. In fact, as also clearly shown by Dehaven et al. (2008), the co-expression of STIM1 and Orai1 dramatically reduces the ability of 2-APB to reverse STIM1 puncta, suggesting that the interaction of STIM1 with Orai1 stabilizes STIM1 at the ER–PM junctions. An additional difference is that the duration of 2-APB application in the Peinelt et al. and Dehaven et al. studies (≥ 10 min) is considerably longer than that that employed in our study (2–5 min) and significantly longer than the time needed for blockade of ICRAC (Prakriya & Lewis, 2001). In the absence of Orai1 co-expression and with 2-APB exposure of 10 min, we did, in fact, observe the reversal of STIM1 puncta following 2-APB addition (data not shown). Thus, the complex effects of 2-APB are likely to arise from modulation of multiple events, including STIM1–Orai1 interaction, STIM1 localization and Orai1 conformational states.

In summary, we have identified the interaction of STIM1 with Orai1 and a downstream conformational change in Orai1 following store depletion as two crucial molecular determinants of CRAC channel regulation. These checkpoints may also be modulated in vivo and may be attractive targets for designing drugs to alter CRAC channel activity in diseased cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jack Waters, Stefan Feske, Beth McNally and Tara Hornell for comments on the manuscript, Beth McNally for help with patch-clamp analysis of Orai1 mutations, Tomasz Zal for discussions on FRET methods, and members of the laboratory for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by grants from the AHA (0630401Z) and NIH (NS057499) to M.P.

Supplementary material

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at:

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2008.162503/DC1

References

- Christian EP, Spence KT, Togo JA, Dargis PG, Patel J. Calcium-dependent enhancement of depletion-activated calcium current in Jurkat T lymphocytes. J Membr Biol. 1996;150:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s002329900030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csutora P, Peter K, Kilic H, Park KM, Zarayskiy V, Gwozdz T, Bolotina VM. Novel role of STIM1 as a trigger for calcium influx factor (CIF) production. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14524–14531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709575200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaven WI, Smyth JT, Boyles RR, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Complex actions of 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB) on store-operated calcium entry. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19265–19273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801535200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S, Giltnane J, Dolmetsch R, Staudt LM, Rao A. Gene regulation mediated by calcium signals in T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:316–324. doi: 10.1038/86318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S, Prakriya M, Rao A, Lewis RS. A severe defect in CRAC Ca2+ channel activation and altered K+ channel gating in T cells from immunodeficient patients. J Exp Med. 2005;202:651–662. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi CS, Isacoff EY. Shedding light on membrane proteins. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon GW, Berry G, Liang XH, Levine B, Herman B. Quantitative fluorescence resonance energy transfer measurements using fluorescence microscopy. Biophys J. 1998;74:2702–2713. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77976-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Feske S, Cruz-Guilloty F, Oh-hora M, Neems DS, Hogan PG, Rao A. Biochemical and functional characterization of Orai proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16232–16243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe A, Christensen K, Swanson JA. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based stoichiometry in living cells. Biophys J. 2002;83:3652–3664. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75365-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepple-Wienhues A, Cahalan MD. Conductance and permeation of monovalent cations through depletion-activated Ca2+ channels (ICRAC) in Jurkat T cells. Biophys J. 1996;71:787–794. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79278-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RS. Calcium signaling mechanisms in T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:497–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RS. The molecular choreography of a store-operated calcium channel. Nature. 2007;446:284–287. doi: 10.1038/nature05637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Lu J, Xu P, Xie X, Chen L, Xu T. Mapping the interacting domains of STIM1 and Orai1 in Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29448–29456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J, Fivaz M, Inoue T, Meyer T. Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9301–9306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702866104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luik RM, Wang B, Prakriya M, Wu MM, Lewis RS. Oligomerization of STIM1 couples ER calcium depletion to CRAC channel activation. Nature. 2008;454:538–542. doi: 10.1038/nature07065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luik RM, Wu MM, Buchanan J, Lewis RS. The elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry: local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER-plasma membrane junctions. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:815–825. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma HT, Venkatachalam K, Parys JB, Gill DL. Modification of store-operated channel coupling and inositol trisphosphate receptor function by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate in DT40 lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6915–6922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107755200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Orai1 subunit stoichiometry of the mammalian CRAC channel pore. J Physiol. 2008;586:419–425. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muik M, Frischauf I, Derler I, Fahrner M, Bergsmann J, Eder P, Schindl R, Hesch C, Polzinger B, Fritsch R, Kahr H, Madl J, Gruber H, Groschner K, Romanin C. Dynamic coupling of the putative coiled-coil domain of Orai1 with STIM1 mediates Orai1 channel activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8014–8022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB. Functional consequences of activating store-operated CRAC channels. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB, Putney JW., Jr Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:757–810. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partiseti M, Le Deist F, Hivroz C, Fischer A, Korn H, Choquet D. The calcium current activated by T cell receptor and store depletion in human lymphocytes is absent in a primary immunodeficiency. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32327–32335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinelt C, Lis A, Beck A, Fleig A, Penner R. 2-APB directly facilitates and indirectly inhibits STIM1-dependent gating of CRAC channels. J Physiol. 2008;586:3061–3073. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.151365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M, Feske S, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Rao A, Hogan PG. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Potentiation and inhibition of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels by 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB) occurs independently of IP3 receptors. J Physiol. 2001;536:3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Separation and characterization of currents through store-operated CRAC channels and Mg2+-inhibited cation (MIC) channels. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:487–507. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopulos PB, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ames JB, Ikura M. Stored Ca2+ depletion-induced oligomerization of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) via the EF-SAM region: An initiation mechanism for capacitive Ca2+ entry. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35855–35862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z, Shoemaker RL, Marchase RB, Blalock JE. Ca2+ modulation of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels is responsible for the inactivation of its monovalent cation current. Biophys J. 2004;86:805–814. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74156-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth PT, Ren D, Miller RJ. Regulation of CXCR4 receptor dimerization by the chemokine SDF-1alpha and the HIV-1 coat protein gp120: a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) study. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:8–17. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M, Beck A, Billingsley JM, Lis A, Parvez S, Peinelt C, Koomoa DL, Soboloff J, Gill DL, Fleig A, Kinet JP, Penner R. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2073–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodarczyk J, Woehler A, Kobe F, Ponimaskin E, Zeug A, Neher E. Analysis of FRET signals in the presence of free donors and acceptors. Biophys J. 2008;94:986–1000. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MM, Buchanan J, Luik RM, Lewis RS. Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:803–813. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Lu J, Li Z, Yu X, Chen L, Xu T. Aggregation of STIM1 underneath the plasma membrane induces clustering of Orai1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:969–976. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M, Navarro-Borelly L, McNally B A, Prakriya M. Orai1 mutations alter ion permeation and Ca2+-dependent inactivation of CRAC channels: evidence for coupling of permeation and gating. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:525–540. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeromin AV, Zhang SL, Jiang W Yu Y, Safrina O, Cahalan MD. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 2006;443:226–229. doi: 10.1038/nature05108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zal T, Gascoigne NR. Photobleaching-corrected FRET efficiency imaging of live cells. Biophys J. 2004;86:3923–3939. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.022087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature. 2005;437:902–905. doi: 10.1038/nature04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifach A, Lewis RS. Calcium-dependent potentiation of store-operated calcium channels in T lymphocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:597–610. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.