Abstract

Animal and in vitro studies have shown that the sympathetic nervous system modulates the contractility of skeletal muscle fibres, which may require adjustments in the motor drive to the muscle in voluntary contractions. In this study, these mechanisms were investigated in the tibialis anterior muscle of humans during sympathetic activation induced by the cold pressor test (CPT; left hand immersed in water at 4°C). In the first experiment, 11 healthy men performed 20 s isometric contractions at 10% of the maximal torque, before, during and after the CPT. In the second experiment, 12 healthy men activated a target motor unit at the minimum stable discharge rate for 5 min in the same conditions as in experiment 1. Intramuscular electromyographic (EMG) signals and torque were recorded and used to assess the motor unit discharge characteristics (experiment 1) and spike-triggered average twitch torque (experiment 2). CPT increased the diastolic blood pressure and heart rate by (mean ±s.d.) 18 ± 9 mmHg and 4.7 ± 6.5 beats min−1 (P < 0.01), respectively. In experiment 1, motor unit discharge rate increased from 10.4 ± 1.0 pulses s−1 before to 11.1 ± 1.4 pulses s−1 (P < 0.05) during the CPT. In experiment 2, the twitch half-relaxation time decreased by 15.8 ± 9.3% (P < 0.05) during the CPT with respect to baseline. These results provide the first evidence of an adrenergic modulation of contractility of muscle fibres in individual motor units in humans, under physiological sympathetic activation.

The activation of the sympathetic nervous system accompanies and supports motor functions. Sympathetic activation maintains or increases the arterial blood pressure when the blood demand from the working muscles increases. In addition, sympathetic activity may directly influence muscle function and motor control by modulating the local muscle blood flow (Thomas & Segal, 2004), muscle contractility (Bowman, 1980; Roatta & Passatore, 2008), proprioceptive activity from muscle spindle afferents (Matsuo et al. 1995; Roatta et al. 2002) and, in pathological conditions, the nociceptive activity from cutaneous and muscle nociceptors (Baron et al. 1999; Janig & Habler, 2000; Passatore & Roatta, 2006). The interest in the effects of sympathetic activity on muscles has recently increased due to the epidemiological and clinical observation that stress and sympathetic hyperactivity are factors of influence for the development and maintenance of musculo-skeletal disorders (Haufler et al. 2000; Sterling, 2004; Bongers et al. 2006; Passatore & Roatta, 2006).

The present study investigates the sympathetic action on muscle contractility and its consequences on the neural drive to muscles, a mechanism previously documented in animal and in vitro studies but almost unexplored in humans. Sympathetic modulation of skeletal muscle fibre contractility is mainly mediated by adrenaline acting on β2 adrenergic receptors located on the sarcolemma and depends on the muscle fibre type (Bowman, 1980). Adrenaline exerts a potentiating effect on type II fibres at high (possibly non-physiological) concentrations and a weakening effect on type I fibres at lower concentrations. This latter effect is attributed to shortening of the muscle fibre twitch force and may produce a pronounced decrease in the force developed during subtetanic contractions (Bowman, 1980). The effect was first documented by Bowman & Zaimis (1958) during electrically elicited contractions of the soleus muscle in the anaesthetized cat. They reported a 33% decrease in duration of the twitch force, and a consequent 36% reduction of the force developed at 10 impulses s−1 stimulation, in response to i.v. injection of the β-adrenergic agonist isoprenaline (Bowman & Zaimis, 1958). The same phenomenon has been later observed in other animal studies (Bowman, 1980) and the intracellular pathways have been more recently elucidated with in vitro studies (Cairns & Dulhunty, 1993; Ha et al. 1999). However, limited evidence is available from human studies.

Marsden & Meadows (1970) observed twitch shortening and decreased force in subtetanic stimulated contraction of the calf muscle, in response to i.v. adrenaline injection. In agreement with these results, the twitch duration was observed to increase in the tibialis anterior muscle in response to β-adrenergic blockade (Alway et al. 1988). However, it is unknown if these effects occur in humans under physiological activation of the sympathetic nervous system and if they have any consequence on the neural control of movement (McAuley & Marsden, 2000).

This human study investigates the effect of sympathetic activation on the discharge rate of individual motor units during voluntary contractions and on the contractility of muscle fibres. Sympathetic activation was obtained by the cold pressor test (CPT) (physiological sympathetic activation) which is known to elicit secretion of adrenaline (Robertson et al. 1979). Considering the notion that type I fibres exhibit a greater sensitivity to adrenaline than type II, and that the potentiating effect on type II fibres would possibly mask the adrenergic effect expected on type I fibres, the present investigation focused on the low-threshold motor units. The tests involved low-force, short-duration contractions in order to exclude the occurrence of fatigue and to ensure that only type I muscle fibres were analysed.

Methods

The study consisted of two experiments which analysed motor unit discharge rates during contractions at constant torque (experiment 1) and motor unit twitch torque during contractions at constant discharge rate (experiment 2). Unless specified, the descriptions of methods refer to both experimental tests. A simulation analysis of motor unit twitch torque was also performed.

Subjects

Eleven (age 21–38 year, mean 27.3 year) and 16 (age 23–38 year, mean 28.3 year) healthy men participated in experiment 1 and 2, respectively. The experimental protocols, approved by the local ethical committee (N-20070017), were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects gave their written informed consent before participation in the experiments.

Experimental set-up

Subjects were asked to refrain from meals and coffee in the hour before the beginning of the experiment. The subject was seated on a dental chair of adjustable height with his right foot fixed to a foot plate. The positions of chair and foot plate were adjusted so that the knee and ankle joint angles were ∼90 deg. The leg was stabilized by Velcro straps and by a vacuum-packed kapok-filled pillow (Ambu, Kristianstad, Sweden) that prevented side movements of the leg without compression of the tissues that could have impaired blood flow to the lower leg. Care was taken in tightly fixing the foot to the foot plate. For this purpose, no padding was used to avoid damping of the torque measurement at the ankle joint. Room temperature was kept constant (22.8 ± 1.2°C) during each experiment.

EMG

Two Teflon-coated stainless steel wire electrodes (A-M Systems, Carlsborg, WA, USA; diameter 50 μm) were inserted in the tibialis anterior muscle with a 25-G needle, ∼1 cm deep at approximately mid-way between the tibia tuberosity and the lateral malleolus. The needle was removed after the insertion, leaving the wire electrodes inside the muscle. The wires were cut to expose only the cross-section. The intramuscular EMG signals were differentially amplified (Counterpoint EMG, Dantec Medical, Skovlunde, Denmark) and band-pass filtered (500 Hz to 5 kHz). The cut-off frequencies chosen for recording intramuscular EMG signals allowed high selectivity of the recording. A reference electrode was placed around the ankle.

In addition to intramuscular EMG, surface EMG signals were recorded in experiment 1 only, using bipolar circular electrodes (1 cm diameter) placed along the muscle fibres direction, 2 cm apart, 2 cm distal from the insertion point of the intramuscular wires and 2 cm lateral to the tibia bone.

Torque

The footplate was equipped with a strain gauge providing a signal proportional to the elastic deformation. This signal was amplified (Amplifier Unit LAU 73.1, Soemer, Lennestadt, Germany) and used to measure the absolute torque level produced at the ankle (0.7 N m V−1; bandwidth 0–50 Hz). In addition, in experiment 2 only, the footplate was also equipped with a load cell (model 5011, charge amplifier J011B10, Kistler Instrument AG, Winterthur, Switzerland), which provided a greater sensitivity and bandwidth for the assessment of small torque oscillations (0.035 N m V−1; bandwidth 0.01–100 Hz).

ECG, blood pressure, subjective pain ratings and temperature

An ECG signal was recorded with two Ag–AgCl surface electrodes (Medicotest, Oelstykke, Denmark) placed on the thorax. The ECG signal was amplified (Counterpoint EMG, Dantec; Denmark), band-pass filtered (20–200 Hz) and acquired on a PC for off-line measurement of the heart rate.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured with a digital blood pressure meter (UA-751, Simonsen & Weel, Vallensbæk Strand, Denmark). The manometer cuff was released after each measure and the arm raised up a few seconds for quick recovery of perfusion regimen in the arm.

The pain intensity was continuously scored by the subjects on an electronic 10 cm visual analog scale (VAS) with the lower extreme labelled ‘no pain’ and the upper extreme labelled ‘most pain imaginable’. Cutaneous temperature was measured by a digital thermometer (Ellab Ltd, Copenhagen, Denmark) with a wire probe taped to the skin, 3–4 cm distal to the intramuscular EMG recording site.

EMG, torque, ECG and VAS were concurrently sampled (12 bit A/D conversion, 10 kHz sampling frequency) and stored on a PC.

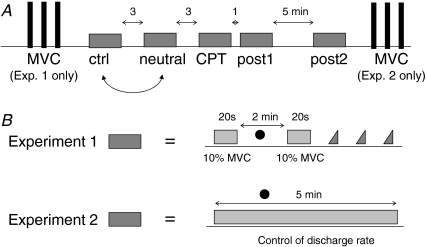

Experimental protocol

The motor tasks were performed in the same conditions in the two experiments: control, neutral, CPT, post1 and post2 (Fig. 1A). In the neutral condition the left hand was immersed in water at 32–35°C (neutral sensation) for 5 min. The sequence of the control and neutral conditions was randomized; however, the neutral condition was not included for the measures of 6 out of 16 subjects in experiment 2. In the CPT condition, the left hand was immersed in iced water (3–4°C) stirred by a peristaltic pump, for 5 min. The subjects could withdraw the hand from the water if the pain became unbearable, in which case the data were excluded from the analysis. In the other conditions (control, post1 and post2) the subject had the left hand in the same position as in neutral and CPT conditions but without water contact and with no other additional constraint. The tasks performed in control and neutral conditions were followed by 3 min rest, the CPT by 1 min rest and the post1 by 5 min rest (Fig. 1A). Systolic and diastolic blood pressures and cutaneous temperature were measured approximately 2–3 min after the beginning of the task.

Figure 1. Experimental protocol and motor tasks.

A, in both experiment 1 and 2 the same motor task (grey box) was repeated in five conditions: control, neutral, CPT, post1 and post2. In the CPT (cold pressor test) condition the left hand was immersed in iced water for the duration of the task. In the neutral condition the left hand was immersed in warm water. Simple execution of the motor task with no additional constraints is performed in the other conditions. The neutral condition was randomized with the control condition. Three maximum voluntary contractions (MVC) were performed, separated by 2 min of rest, at the beginning (experiment 1) or at the end (experiment 2) of the experimental session. B, in experiment 1 the motor task consisted of two 20 s isometric contractions (ankle dorsiflexion) at 10% MVC separated by 2 min of rest during which arterial blood pressure was measured. After the second 10% MVC contraction, three ramp contractions were performed (from 0 to 10% MVC in 10 s). In experiment 2 the motor task consisted of a 5 min isometric contraction in which the discharge rate of the target motor unit was maintained as low as possible. The dots represent time of arterial blood pressure and cutaneous temperature measurement.

The maximal voluntary contraction torque (MVC) was measured as the maximum torque developed in three subsequent maximal ankle dorsiflexions of ∼3 s duration, separated by 2 min intervals at the beginning (experiment 1) or at the end (experiment 2) of the experimental protocol.

Tasks – Experiment 1

The subject was provided with visual feedback on the ankle joint torque by means of a digital oscilloscope and was trained for matching a torque target of 10% MVC. The subject performed two 20 s isometric ankle dorsiflexions at 10% MVC, separated by 2 min intervals of rest. After the second contraction, he was asked to perform three ramp contractions in dorsiflexion from 0% to 10% MVC in 10 s using the torque feedback, separated by 20 s intervals of rest (Fig. 1B). The set of two constant-torque and three ramp contractions was repeated in each of the five conditions.

Tasks – Experiment 2

The subject was provided with visual and auditory feedback of the intramuscular EMG signal and trained for increasing and decreasing the discharge rate of a motor unit (target unit) by changing the torque in dorsiflexion. Because the recording was highly selective, the activities of only one or two motor units were usually recorded at low contraction forces (< 10% MVC). The motor unit with the highest action potential was chosen as target unit. The recording session was preceded by ∼20 min of training for maintaining the target motor unit active at the minimum discharge rate and for recruiting the unit over repeated contractions separated by resting intervals. The task consisted in performing an isometric ankle dorsiflexion activating the target motor unit at the minimum rate for 5 min and was repeated in each of the five conditions. The MVC was measured with the same modalities as in experiment 1 at the end of the session for avoiding any perturbations of the mechanical system before the recordings and was used to compute the submaximal contraction level at which the target motor unit was activated.

Signal analysis

In both experiments, the heart rate was extracted from the ECG signal as the inverse of the R-R interval. The R waves were detected by a threshold-crossing algorithm developed in Matlab. The average and maximum R-R interval were computed for each condition after applying a 20-sample moving average filter. In addition, values of systolic and diastolic blood pressure and cutaneous temperature were averaged over each condition. The average and maximum values of the VAS ratings were computed for each contraction.

The motor unit action potentials were identified from the intramuscular recordings with a decomposition algorithm (McGill et al. 2005). In experiment 1, the times of occurrence of the identified intramuscular action potentials were used to estimate the instantaneous discharge rate of the active motor units during the constant torque contractions. Only the motor units identified in all five conditions, as established by the analysis of the shape of their action potentials, were considered for further analysis. The discharge rate was characterized by its mean value over the 20 s contraction and the coefficient of variation of the interspike interval, defined as the ratio (%) between s.d. and mean of the interspike interval. The recruitment threshold of the identified motor units was estimated from the ramp contractions as the torque (average over the three ramp contractions) corresponding to the first motor unit discharge followed by another discharge at distance < 200 ms. The torque signal during the constant-torque contractions was averaged over the 20 s and its coefficient of variation (CoV) was computed to quantify steadiness. The amplitude of the surface EMG signal was estimated as the root mean square (RMS) value over the 20 s contraction.

For experiment 2, the times of occurrence of the action potentials were used as trigger for averaging the joint torque signal and extracting the average twitch torque of the target motor unit (Stein et al. 1972). Because with this technique the estimated twitch torque is affected by the distance of the previous and successive discharge (Nordstrom et al. 1989), for each subject the minimum interspike interval for trigger selection was the same in all conditions and was set to 125 ms. However, in three subjects the half-relaxation point was not reached within 125 ms. For the half-relaxation time to be correctly estimated, in these three subjects the minimum interspike interval was set to 175 ms for all conditions. One motor unit twitch torque estimate was extracted from each contraction of 5 min. Time-to-peak, half-relaxation time, and peak amplitude were computed from the average twitch torque. First, the peak value was identified as the maximum value of the twitch and the time-to-peak was computed as the interval between the trigger event and the time instant corresponding to the peak. The minimum was identified as the minimum value of the twitch in the interval between the trigger and the peak and the peak amplitude was computed as the difference between the peak and the minimum values. The half-relaxation time was computed as the interval between the peak and the instant when the twitch crossed (downwards) the value = (minimum + peak)/2.

Statistical analysis

For both experiments, non-parametric statistical analysis was adopted because the normality tests failed for some of the analysed variables. The Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare systemic variables and VAS score in the two studies. The Friedman ANOVA for repeated measures was used to assess an effect of condition (control, warm, CPT, post1 and post2) on the measured variables. When ANOVA was significant (P < 0.05), pair-wise comparisons were obtained by the Wilcoxon matched pairs test. The Wilcoxon paired test was also used in experiment 2 for the comparison between the control and the neutral condition, performed by a subgroup of subjects. In experiment 1, a two-way ANOVA for repeated measures was adopted to analyse the discharge properties of single motor units, with factors the condition and the contraction (first and second contraction in each condition). Values are presented as mean and s.d. in the text and as mean and standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) in the figures.

Simulations

A simulation analysis was performed to interpret the experimental findings on single motor unit spike-triggered average torque (experiment 2). The simulations were based on a modified version of the equation for the motor unit twitch torque proposed by Fuglevand et al. (1993), based on the response of a critically damped second order system:

| (1) |

where F is the twitch torque, t is the time variable, P is the peak torque, and T is the time-to-peak. In this model, the time-to-peak T implicitly defines the half-relaxation time, which is approximately equal to 5/3T. Thus, eqn (1) cannot simulate changes in half-relaxation time independent of changes in time-to-peak. However, animal studies suggest that the expected main effect in motor unit twitch torque with sympathetic activation is a reduction in relaxation time without substantial changes in time-to-peak (Bowman, 1980), due to a faster rate of reuptake of calcium in the sarcoplasmatic reticulum (Ha et al. 1999). Thus, a modified model was used to characterize the relaxation phase:

| (2) |

with Ohrt being the half-relaxation time of the twitch.

Therefore, the twitch torque was described as:

| (3) |

The developed torque for each motor unit was obtained by convolution of eqn (3) with the simulated discharge pattern of the unit (Fuglevand et al. 1993). Discharge patterns were obtained by fixing a value for the average discharge rate and introducing a Gaussian variability on the discharge times; the s.d. of the Gaussian function varied in the range 0–60%.

The activity of each motor unit was simulated for intervals of 300 s, which was the same duration as the contractions with feedback on motor unit potentials in experiment 2. The spike-triggered average twitch was extracted from the simulated torque signal in the same way as for the experimental recordings. However, the spike-triggered averaging was applied to the torque produced by only one motor unit in each simulation, without the contributions of the other active units. This choice was due to the fact that the model by Fuglevand et al. (1993) assumes linearity of the summation of the twitches; thus, when using this model, uncorrelated activity does not contribute to the average if a sufficient number of triggers is used (Stein et al. 1972). The simulations did not aim at investigating the effect of the number of triggers or contraction level on the estimated twitch but rather had the purpose of assessing the effect of changes in the target unit twitch torque on the estimated twitch properties. For this purpose, it was not necessary to simulate the spike-triggered averaging procedure for a full set of active motor units when using a linear model of twitch summation. However, issues in the interpretation of the simulation results may arise when considering a potential nonlinearity in the summation of experimental twitches, which was not modelled (see Discussion). In the simulations, Ohrt was varied while maintaining the time-to-peak T equal to 90 ms (Fuglevand et al. 1993; Van Cutsem et al. 1997). The choice of 90 ms for the time-to-peak of the simulated twitch led to an estimated twitch by the simulated procedure of spike-triggered averaging similar to the twitches estimated experimentally.

Results

Pain and sympathetic activation

No significant difference was observed in both the VAS score and the systemic variables in the two experiments, which included the same conditions. Therefore the data from the two subject groups (n = 11 in experiment 1 and n = 12 in experiment 2 after exclusion of four subjects; see below for exclusion criteria), were pooled for the description of the systemic response to CPT.

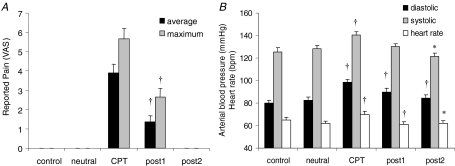

CPT evoked a persistent painful sensation that outlasted the duration of the test (Fig. 2A). The peak VAS score was 5.6 ± 2.5 (range: 1.8–10) during the CPT and 2.6 ± 2.1 (range: 0–7.4) during post1 (P < 0.01). The painful sensation vanished in all subjects before post2 (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Pain and sympathetic activation.

A, mean (black) and maximum (grey) values for subjective pain intensity rating on a 0–10 visual analog scale (VAS) for the four conditions. Values in post1 are significantly smaller than their respective values in CPT. B, effect of CPT on diastolic (black) and systolic (grey) arterial blood pressure and on heart rate (white). *Significantly different from control, P < 0.05; †significantly different from control, P < 0.01. The results are from pooled data from experiments 1 and 2 (n = 23 in all conditions, except for the neutral condition in which n = 17).

The CPT produced an increase in diastolic blood pressure from 79.8 ± 12.7 to 98.4 ± 11.7 mmHg (P < 0.01), in systolic blood pressure from 125.6 ± 16.4.0 to 140.6 ± 14.0 mmHg (P < 0.01), and in heart rate from 65.0 ± 10.2 to 69.8 ± 12.2 beats min−1 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2B). Diastolic blood pressure remained significantly elevated in post1 and post2 (P < 0.01) with respect to control whereas heart rate decreased below control values in the subsequent post1 (P < 0.01) and post2 (P < 0.05) sessions. Hand immersion in neutral water did not produce any significant change in heart rate and arterial blood pressure.

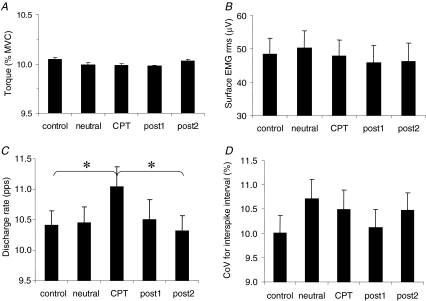

Experiment 1

The average torque was maintained at the target level of 10% MVC (Fig. 3A) during the duration of all contractions. In all conditions the difference between exerted and target torque was < 0.5% and this difference did not depend on the condition. Moreover, the CoV of torque was not affected by the condition (mean over all conditions, 1.5 ± 0.7%). The RMS value of the surface EMG signal did not depend on the condition (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Effects of CPT in costant-torque contractions Torque.

(n = 11 subjects) (A), amplitude of the surface EMG signal (rms) (n = 11 subjects) (B), discharge rate of individual motor units (n = 18 motor units) (C), and coefficient of variation (CoV) for interspike interval (n = 18 motor units) (D), in the five conditions. The results from the two contractions within each condition have been averaged. *Significantly different, P < 0.05.

Cutaneous temperature decreased slightly during the experiment, from 30.9 ± 1.4°C (control) to 30.5 ± 1.6°C post2 (P < 0.05).

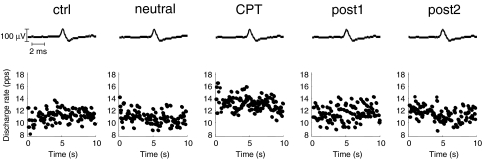

A total of 18 motor units were identified in the two contractions of all five conditions. An example of identification of a motor unit across conditions in one subject is reported in Fig. 4. The motor unit action potential is reported in the upper trace, and the discharge rate of the motor unit in the lower trace, for one contraction in each of the five conditions. In this example, the discharge rate increased in the CPT condition with respect to the other conditions. Because all the investigated variables did not depend on the contraction within each condition, the values were averaged over the two contractions. During CPT, motor unit discharge rate was greater (11.1 ± 1.4 pulses s−1) as compared to control (10.4 ± 1.0 pulses s−1) and post2 (10.3 ± 1.1 pulses s−1) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3C), whereas the CoV of interspike interval did not depend on the condition (Fig. 3D). The recruitment threshold of the investigated motor units did not change across conditions (average over all conditions, 4.2 ± 2.8% MVC).

Figure 4. Example of changes in discharge rate during CPT.

Average action potentials of a motor unit identified from the intramuscular EMG recordings during the constant torque contractions at 10% MVC in the five conditions (upper traces). The instantaneous discharge rate for the identified motor unit is shown for the first 10 s of one of the 10% MVC contractions in each of the five conditions (lower traces).

Experiment 2

In experiment 2, four subjects were excluded from the analysis. One of them interrupted the CPT due to pain, another could not identify the same target motor unit in all conditions using the visual feedback, and for two the estimated twitch torque was below the noise level of the torque signal. Results are thus presented for the remaining 12 subjects (age, 28.4 ± 4.6 year). Six of these subjects performed a contraction in the neutral condition.

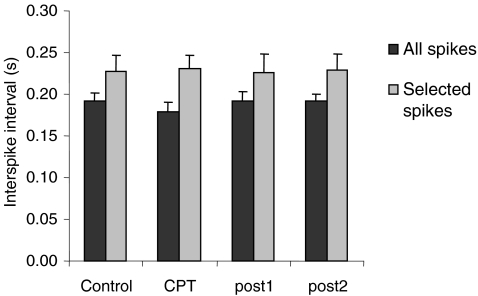

The skin temperature decreased from 31.8 ± 0.6°C (control) to 31.3 ± 0.7°C (post2) during the experiment (P < 0.05). The average torque during the 5 min contractions was not different among conditions (across all conditions, 4.8 ± 4.8% MVC). In only one subject it exceeded 10% MVC (16% MVC). During CPT there was a tendency for poorer control of the target motor unit. The interspike interval decreased from 193 ± 32 ms (control) to 180 ± 36 ms (CPT) (Fig. 5) and the CoV for interspike interval increased from 60.7 ± 22.2% (control) to 71.8 ± 22.7% (CPT). However, these changes were not statistically significant. Because the interspike interval of the trigger action potentials may affect the twitch torque estimation, the interspike interval was also analysed for the action potentials selected as triggers. The interval between the trigger action potentials and the previous action potentials was similar in all conditions without statistical differences (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Interspike interval for the trigger action potentials.

Mean interspike interval computed from all detected action potentials of the target motor unit (black) and from the action potentials selected as trigger for the spike-triggered averaging (grey). In the latter case, the interval between the selected and the preceding action potential is considered.

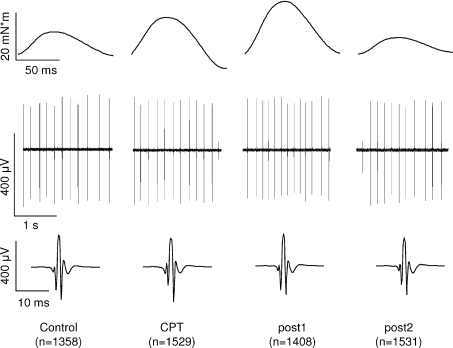

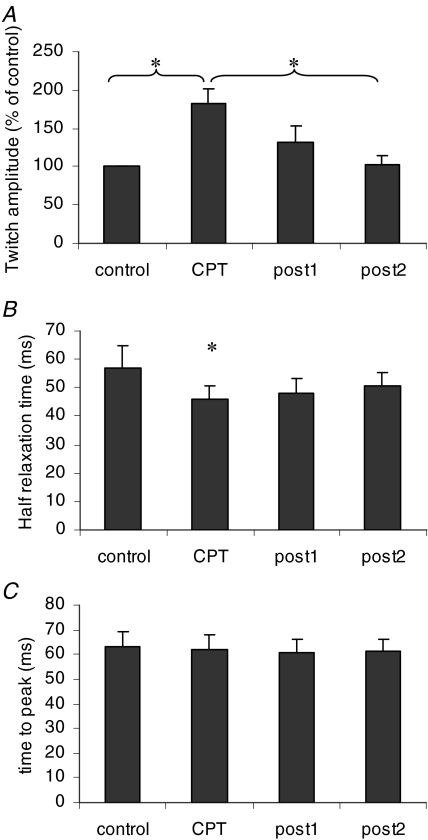

An example of pattern of response of the twitch torque to the CPT is depicted in Fig. 6. In this subject the twitch torque exhibited a marked increase in peak amplitude during CPT that persisted in the subsequent post1 session. The half-relaxation time also changed during CPT. On average, CPT induced an increase in peak amplitude of the twitch torque from 2.7 ± 2.8 to 4.2 ± 4.3 mN m (P < 0.05; percentage increase 82.0 ± 70.6%) (Fig. 7A). CPT also induced a decrease in the half-relaxation time from 56.7 ± 25.2 ms to 46.1 ± 15.2 ms (P < 0.05; percentage decrease 15.8 ± 9.3%) (Fig. 7B). These parameters returned to control after the CPT condition, with no significant differences between control, post1, and post2 conditions. The time-to-peak did not change in any of the conditions (average over all conditions, 61.8 ± 2.8 ms) (Fig. 7C). In the six subjects who performed the task under the neutral condition, there was no significant difference between the control and neutral conditions for any of the analysed variables (interspike interval: 195 ± 37 versus 181 ± 18 ms; interspike interval variability: 48 ± 18 versus 50 ± 19%; peak amplitude: 3.7 ± 3.5 versus 2.5 ± 2.6 mN m; half-relaxation time: 65 ± 32 versus 67 ± 22 ms, time-to-peak: 55 ± 13 versus 55 ± 9 ms).

Figure 6. Example of changes in motor unit twitch torque during CPT.

Effect of CPT on the estimated twitch torque for a single motor unit (upper trace). The activity of the target motor unit, which is used for triggering, is shown by intramuscular EMG recordings for the different contractions (middle trace). The lower trace shows the intramuscular action potential shape of the target motor unit. Each curve in the upper and lower traces is obtained by spike-triggered averaging of the number (n) of waveforms indicated in parentheses.

Figure 7. Effects of CPT on the twitch torque.

Twitch amplitude (A), half-relaxation time (B), and time-to-peak (C) of the twitch torque in the four conditions. *Significantly different, P < 0.05.

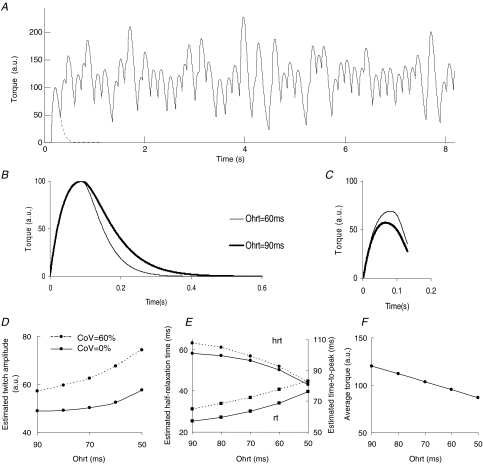

Simulations

Because the main effect expected on the motor unit twitch torque was shortening during CPT, a simulation study was performed to determine if shortening of the twitch could explain the increase in estimated twitch amplitude, as observed in experiment 2. The simulations were performed with the modified motor unit twitch torque model presented in eqn (3).

The contraction of a single slow twitch motor unit (time-to-peak = 90 ms) was simulated with discharge rate of 7 pulses s−1. Figure 8A shows an example of the simulated torque. When the half-relaxation time (Ohrt) was reduced from 90 to 60 ms (Fig. 8B) the amplitude of the estimated twitch increased by 28% and the estimated time-to-peak increased by 25% (Fig. 8C). Moreover, the estimated half-relaxation time decreased from 62 to 51 ms. The general trends are shown in Fig. 8D–F. The estimated twitch amplitude increased with decreasing half-relaxation time of the twitch (Fig. 8D) and a similar trend was exhibited by the estimated time-to-peak (Fig. 8E). The estimated half-relaxation time decreased with decreasing half-relaxation time of the twitch (Fig. 8E). Finally, a decrease in half-relaxation time also resulted in decreased average torque exerted by the motor unit (Fig. 8F).

Figure 8. Simulations of the spike-triggered averaging.

A motor unit discharge pattern was simulated with average discharge rate of 7 pulses s−1 and variable coefficient of variation for the interspike interval. The simulated motor unit twitch had amplitude equal to 100 arbitrary units (a.u.), time-to-peak (T) of 90 ms, and half-relaxation time (Ohrt) in the range 50–90 ms. A, the time course of the developed torque in one of the simulations (CoV for the interspike interval: 30%, Ohrt: 90 ms). The single twitch torque is drawn with a dashed line on the left side of the plot. B, examples of torque twitches used for the simulations with Ohrt = 90 ms (thick line) and 60 ms (thin line). C, estimated torque twitches obtained by spike-triggered averaging the torque signal resulting from two simulations with the twitches shown in B: Ohrt = 90 ms (thick line) and 60 ms (thin line); CoV for interspike interval: 60%; minimum interspike interval: 130 ms. D, amplitude of the estimated twitch torque as a function of the simulated half-relaxation time. E, same as in D for the estimated time-to-peak and half-relaxation time. F, as in D for the average torque developed by the motor unit. In D, E and F, the simulations were based on a simulated discharge without variability (continuous line) or with coefficient of variation for the interspike interval of 60% (dashed line).

Figure 8D–F also shows the effect of introducing a variability in the discharge rate similar to that experimentally observed in experiment 2 (60%). Introducing this level of variability determined an increase in the estimated peak amplitude (Fig. 8D) and time-to-peak (Fig. 8E) of the twitch. However, interspike interval variability had a limited effect on the estimated half-relaxation time (Fig. 8E).

The simulations indicated that a decrease in half-relation time without changes in twitch amplitude may result in increased amplitude of the twitch estimated by spike-triggered averaging.

Discussion

The results have shown central and peripheral effects of sympathetic activation induced by the CPT: increased motor unit discharge rate during constant torque contractions and increased amplitude and decreased half-relaxation time of the spike-triggered twitch torque.

Increased motor unit discharge rates during constant torque contraction could have resulted from an increased activation of antagonist muscles during the CPT. Experimental stress, more often in the form of mental demand, has been shown to cause an increase in the activity of muscles not primarily involved in the task, especially for neck–shoulder muscles (Waersted, 2000). The activity of antagonist muscles was not monitored in this study and thus the possibility of increased antagonist activity cannot be ruled out; however, antagonist activation does not explain the effects observed on the motor unit twitch torque.

Alternatively, increased neural drive to the tibialis anterior muscle was required to compensate for a weakening effect of CPT on the tibialis anterior muscle fibres. Such an effect could be attributed to both indirect (vascular) and direct sympathetic action on the contractility of skeletal muscle fibres.

Sympathetic activation by CPT may reduce muscle blood flow to lower limbs (Wray et al. 2007) and a reduction in muscle blood flow decreases muscle force, during sustained contractions, particularly in type I muscle fibres (Hobbs & McCloskey, 1987). However, reduced perfusion cannot account for the decrease in twitch half-relaxation time, observed in experiment 2, as muscle ischaemia slows the relaxation rate (Wiles & Edwards, 1982).

Since slow-twitch muscle fibres were involved in the analysed motor task, a weakening effect of the CPT on tibialis anterior muscle fibres is compatible with the direct modulation of the contractile machinery by catecholamines, adrenaline in particular. Catecholamines, acting via β2 adrenergic receptors located on the sarcolemma, have indeed been shown to produce a marked weakening effect on slow-twitch muscle fibres in animal studies (Bowman, 1980). The weakening action, elucidated in more recent in vitro studies (Cairns & Dulhunty, 1993; Ha et al. 1999), is due to a potentiation of Ca2+ reuptake into the sarcoplasmatic reticulum, which reduces the permanence of Ca2+ in the cytoplasm and results in a shortened twitch response. In subtetanic contractions, this effect lowers the extent of twitch fusion and decreases the average force, as reported for electrically elicited contractions in response to i.v. injection of adrenaline (Bowman & Zaimis, 1958; Marsden & Meadows, 1970; Bowman, 1980). In order to substantiate the hypothesis that the increased discharge rate during CPT, observed in experiment 1, was associated to changes in muscle fibre contractility, the effect of sympathetic activation on muscle contractility was analysed in this study by direct estimation of the twitch torque exerted by individual low-threshold motor units (experiment 2).

The results of experiment 2 showed a reduction in the twitch half-relaxation time which strongly supports the hypothesis of adrenergic modulation of contractility and is also in accordance with the observed increased drive to the muscle due to reduced force generation by motor units. Reduced force generation capacity as a consequence of reduced half-relaxation time was also confirmed by the simple simulation analysis performed in this study (Fig. 8F). The observed change in estimated twitch properties is not convincingly explained by factors other than sympathetic activation (Wiles & Edwards, 1982). For instance, increased relaxation rate is reported to occur with increase in muscle temperature (Wiles & Edwards, 1982). However, there is no basis to support the possibility of increased muscle temperature during CPT, given that cutaneous temperature slowly decreased throughout the recording session and that muscle and cutaneous temperatures are expected to be linearly correlated (Hopf & Maurer, 1990).

Although the results on twitch half-relaxation time are in agreement with those obtained in animal studies, the observed increase in twitch amplitude with CPT was an unexpected finding. The twitch amplitude was reported to decrease or remain unchanged in animal and human studies in which the effect of adrenaline injection was investigated in slow-twitch muscles (Marsden & Meadows, 1970; Bowman, 1980). Although small increases in twitch amplitude have been observed in in vitro slow-twitch muscle fibres subjected to β2 adrenergic receptor agonists (Ha et al. 1999), the amount of these changes is not compatible with the marked amplitude increase observed in the present study. Moreover, an increase in twitch amplitude does not explain the observed increase in discharge rate in experiment 1. Thus, it is unlikely that the increase in amplitude of the estimated twitch torque reflected a real torque potentiation.

Several mechanisms may have contributed to alter the estimation of the twitch amplitude. Diffuse sympathetic activation, affecting vessel tone and blood volume may have modified the stiffness of the muscolo-tendineous system. Changes in stiffness and resting tension of the tissues are known to play a relevant role when measuring muscle contractility from a relaxed state (Troiani et al. 1999).

Another factor of influence on twitch amplitude is temperature. The amplitude of the estimated twitch torque was shown to increase by 178% when the overlying skin temperature increased from 33 to 45°C (Farina et al. 2005), during warming-up by an external heater. However, as mentioned above, muscle temperature is unlikely to have a significant role in the present results.

An increase in the amount of motor unit synchronization may partly account for the increase in amplitude of the estimated twitch during CPT, because of the sensitivity of the spike-triggered averaging technique to synchronization (Taylor et al. 2002). However, the present results suggest that an effect of synchronization was probably minor. Motor unit synchronization indeed does not decrease the estimated half-relaxation time whereas it decreases the estimated time-to-peak (Taylor et al. 2002), contrary to the observations of this study. Moreover, the degree of synchronization does not affect the average torque level and thereby cannot account for the increased discharge rate observed in experiment 1; finally, a higher degree of synchronization may increase the surface EMG amplitude and reduce torque steadiness (Yao et al. 2000), which was not observed. It must, however, be pointed out that surface EMG amplitude may have not been a measure sensitive enough for detecting small changes in the statistics of low-threshold motor unit discharge patterns (Farina et al. 2008b); for example, in experiment 1, this measure did not detect the increase in discharge rate of low-threshold motor units.

Another mechanism that may have been responsible for the increase in amplitude of the estimated twitch torque is the decreased twitch fusion (Nordstrom et al. 1989) which occurs as a consequence of twitch shortening. This effect was analysed in this study with simple simulations which showed that a selective reduction in half-relaxation time generates an increase in the estimated twitch amplitude. The simulations did not include several mechanisms which may occur experimentally. For example, the model of twitch summation was linear and thus the spike-triggered average was applied during activation of a single motor unit. However, in experimental conditions nonlinear summation of motor unit twitch forces may occur, although the degree of nonlinearity is small when the muscle is partially active (Sandercock, 2005). Due to the limitations of the current simulations, quantitative values in the changes observed cannot be directly compared with experimental data; however, the simulations provided information on qualitative changes of estimated twitch parameters in response to changes in the true values. In particular, they allowed us to evidence that an increase in estimated twitch amplitude may not correspond to an actual change in twitch amplitude but can result from an increase in half-relaxation time as well as from an increase in the interspike interval variability (Fig. 8D).

The simulations also provided other findings worthy of note. The spike-triggered averaging technique underestimated relative changes in half-relaxation time. For example, a reduction from 90 to 60 ms (–33%) in the actual half-relaxation time resulted in a 15% reduction in the estimated half-relaxation time (Fig. 8E). Considering also that half-relaxation time can be slightly overestimated for larger variability of the interspike interval, the 19% reduction in half-relaxation time observed in experiment 2 during CPT may reflect a more pronounced effect in the actual twitch torque of the tested motor units.

The interpretation of reduced force generated by the low-threshold motor units at fixed discharge rate does not explain the unchanged recruitment threshold. Because the recruitment threshold is the sum of the forces produced by the units recruited prior to the motor unit under study, a reduction in threshold was expected. However, the finding of unchanged recruitment threshold was consistent in both experiments. In experiment 2 the threshold was not directly measured but the average torque at which the target unit was activated at the minimum discharge rate, which is related to the recruitment threshold, was not different among conditions. However, the potential change in threshold should have been very small due to the very low joint forces exerted and was possibly not detected due to limited sensitivity of the measure.

The combined results of experiments 1 and 2 support the hypothesis that during sympathetic activation the force generation capacity of slow-twitch muscle fibres decreases, because of the increased relaxation rate of the twitch torque. Other factors which may explain some of the observations of this study are unlikely to justify the concomitant results on both discharge rate and twitch torque. Thus, the results indicate an effective modulatory action on muscle contractility by the sympathetic nervous system, physiologically activated by CPT. Previous direct evidence of this effect, on the contrary, relied exclusively on pharmacological interventions, such as i.v. or i.a. injections of adrenaline and adrenergic agonists and antagonists.

The effects of physiological sympathetic activation on electrically stimulated contractions of the abductor pollicis were also investigated by Wright et al. (2000), although with the aim of analysing the influence of perfusion pressure on muscle force. During sympathetic activation, they observed potentiation of the twitch force with no evidence of twitch shortening. These results seem at variance with ours; however, the comparison is not direct because of several differences in the experimental protocols. The results by Wright et al. (2000) were obtained from the fatigued muscle, a condition that makes the muscle more sensitive to changes in blood perfusion as well as to catecholamines (Clausen & Nielsen, 2007; Bowman, 1980). Moreover, fast-twitch muscle fibres were probably recruited by the electrical stimulation. These important differences in methodology may have masked the direct adrenergic effect on the contractility of slow-twitch fibres.

Functional implications

The faster relaxation of slow-twitch fibres could allow for more rapid switching between agonist–antagonist activations in fast flexion–extension movements, as needed in a fight or flight reaction. However, the effect of twitch shortening is not beneficial when sympathetic activation occurs independently of a prominent motor activity, e.g. in presence of psychosocial stress. The sympathetically mediated muscle weakening would increase the neural drive to the muscle and the energetic cost of the contraction. Thus, the change in contractility would interfere with motor control and require the adoption of suboptimal motor strategies. The adrenergic effect on slow twitch fibres has been often implicated in the occurrence of tremor (Marsden & Meadows, 1970; Bowman, 1980; McAuley & Marsden, 2000) and is considered the cause of tremor occasionally arising in asthmatic patients when treated with β2-agonists (Waldeck, 2002). Both the increased metabolic activity and the altered motor control may be cofactors in the development of chronic muscle pain syndromes (Sjogaard et al. 2000; Passatore & Roatta, 2006).

Changes in motor unit twitch torque resembling those reported in the present study have been previously observed in response to experimental pain in the masseter (Sohn et al. 2004) and tibialis anterior muscles (Farina et al. 2008a). The VAS pain scores reported in those studies for i.m. injection of hypertonic saline or capsaicin are similar to those obtained in this study during the CPT. The hypothesis that the sympathetic system activated by experimental muscle pain could have played a role in the modulation of muscle fibre contractility (Farina et al. 2008a) is supported by the results of this study.

In summary, for the first time the modulatory action exerted by the sympathetic nervous system on muscle contractility and motor unit discharge rate has been investigated during voluntary contractions, in individual motor units, and under physiological sympathetic activation in humans. The results support the notion that catecholamines modulate contractility of low-threshold motor units and emphasize the tight link between autonomic and motor systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Corrado Cescon for the help in data analysis. The European project ‘Cybernetic Manufacturing Systems’ (CyberManS; contract nr. 016712) (DF) supported this study.

References

- Alway SE, Hughson RL, Green HJ, Patla AE. Human tibialis anterior contractile responses following fatiguing exercise with and without β-adrenoceptor blockade. Clin Physiol. 1988;8:215–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1988.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Levine JD, Fields HL. Causalgia and reflex sympathetic dystrophy: does the sympathetic nervous system contribute to the generation of pain? Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:678–695. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199906)22:6<678::aid-mus4>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers PM, Ijmker S, van den Heuvel S, Blatter BM. Epidemiology of work related neck and upper limb problems: psychosocial and personal risk factors (part I) and effective interventions from a bio behavioural perspective (part II) J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16:279–302. doi: 10.1007/s10926-006-9044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman WC. Effects of adrenergic activators and inhibitors on the skeletal muscles. In: Szekeres L, editor. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, Adrenergic Activators and Inhibitor. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 1980. pp. 47–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman WC, Zaimis E. The effects of adrenaline, noradrenaline and isoprenaline on skeletal muscle contractions in the cat. J Physiol. 1958;144:92–107. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1958.sp006088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns SP, Dulhunty AF. The effects of b-adrenoceptor activation on contraction in isolated fast- and slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:1133–1141. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen T, Nielsen OB. Potassium, Na+,K+-pumps and fatigue in rat muscle. J Physiol. 2007;584:295–304. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.136044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Arendt-Nielsen L, Graven-Nielsen T. Effect of temperature on spike-triggered average torque and electrophysiological properties of low-threshold motor units. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:197–203. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00059.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Arendt-Nielsen L, Roatta S, Graven-Nielsen T. The pain-induced decrease in low-threshold motor unit discharge rate is not associated with the amount of increase in spike-triggered average torque. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008a;119:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Cescon C, Negro F, Enoka RM. Amplitude cancellation of motor-unit action potentials in the surface electromyogram can be estimated with spike-triggered averaging. J Neurophysiol. 2008b;100:431–440. doi: 10.1152/jn.90365.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglevand AJ, Winter DA, Patla AE. Models of recruitment and rate coding organization in motor-unit pools. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:2470–2488. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha TN, Posterino GS, Fryer MW. Effects of terbutaline on force and intracellular calcium in slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1717–1724. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haufler AJ, Feuerstein M, Huang GD. Job stress, upper extremity pain and functional limitations in symptomatic computer users. Am J Ind Med. 2000;38:507–515. doi: 10.1002/1097-0274(200011)38:5<507::aid-ajim3>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs SF, McCloskey DI. Effects of blood pressure on force production in cat and human muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:834–839. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.2.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf HC, Maurer K. Temperature dependence of the electrical and mechanical responses of the adductor pollicis muscle in humans. Muscle Nerve. 1990;13:259–262. doi: 10.1002/mus.880130314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janig W, Habler HJ. Sympathetic nervous system: contribution to chronic pain. Prog Brain Res. 2000;129:451–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden CD, Meadows JC. The effect of adrenaline on the contraction of human muscle. J Physiol. 1970;207:429–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo R, Ikehara A, Nokubi T, Morimoto T. Inhibitory effect of sympathetic stimulation on activities of masseter muscle spindles and the jaw jerk reflex in rats. J Physiol. 1995;483:239–250. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley JH, Marsden CD. Physiological and pathological tremors and rhythmic central motor control. Brain. 2000;123:1545–1567. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.8.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill KC, Lateva ZC, Marateb HR. EMGLAB: an interactive EMG decomposition program. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;149:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom MA, Miles TS, Veale JL. Effect of motor unit firing pattern on twitches obtained by spike-triggered averaging. Muscle Nerve. 1989;12:556–567. doi: 10.1002/mus.880120706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passatore M, Roatta S. Influence of sympathetic nervous system on sensorimotor function: whiplash associated disorders (WAD) as a model. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;98:423–449. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roatta S, Passatore M. Autonomic effects on skeletal muscles. In: Binder MD, Hirokawa N, Windhorst U, editors. Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2008. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Roatta S, Windhorst U, Ljubisavljevic M, Johansson H, Passatore M. Sympathetic modulation of muscle spindle afferent sensitivity to stretch in rabbit jaw closing muscles. J Physiol. 2002;540:237–248. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.014316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D, Johnson GA, Robertson RM, Nies AS, Shand DG, Oates JA. Comparative assessment of stimuli that release neuronal and adrenomedullary catecholamines in man. Circulation. 1979;59:637–643. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.59.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock TG. Summation of motor unit force in passive and active muscle. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2005;33:76–83. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200504000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjogaard G, Lundberg U, Kadefors R. The role of muscle activity and mental load in the development of pain and degenerative processes at the muscle cell level during computer work. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;83:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s004210000285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn MK, Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L, Svensson P. Effects of experimental muscle pain on mechanical properties of single motor units in human masseter. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:76–84. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RB, French AS, Mannard A, Yemm R. New methods for analysing motor function in man and animals. Brain Res. 1972;40:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling M. A proposed new classification system for whiplash associated disorders – implications for assessment and management. Man Ther. 2004;9:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AM, Steege JW, Enoka RM. Motor-unit synchronization alters spike-triggered average force in simulated contractions. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:265–276. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GD, Segal SS. Neural control of muscle blood flow during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:731–738. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00076.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiani D, Filippi GM, Bassi FA. Nonlinear tension summation of different combinations of motor units in the anesthetized cat peroneus longus muscle. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:771–780. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cutsem M, Feiereisen P, Duchateau J, Hainaut K. Mechanical properties and behaviour of motor units in the tibialis anterior during voluntary contractions. Can J Appl Physiol. 1997;22:585–597. doi: 10.1139/h97-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waersted M. Human muscle activity related to non-biomechanical factors in the workplace. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;83:151–158. doi: 10.1007/s004210000273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldeck B. β-Adrenoceptor agonists and asthma – 100 years of development. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;445:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles CM, Edwards RH. The effect of temperature, ischaemia and contractile activity on the relaxation rate of human muscle. Clin Physiol. 1982;2:485–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1982.tb00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray DW, Donato AJ, Nishiyama SK, Richardson RS. Acute sympathetic vasoconstriction at rest and during dynamic exercise in cyclists and sedentary humans. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:704–712. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00984.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JR, McCloskey DI, Fitzpatrick RC. Effects of systemic arterial blood pressure on the contractile force of a human hand muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1390–1396. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.4.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao W, Fuglevand AJ, Enoka RM. Motor-unit synchronization increases EMG amplitude and decreases force steadiness of simulated contractions. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:441–452. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.1.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]