Abstract

The species Campylobacter jejuni is considered naturally competent for DNA uptake and displays strong genetic diversity. Nevertheless, nonnaturally transformable strains and several relatively stable clonal lineages exist. In the present study, the molecular mechanism responsible for the nonnatural transformability of a subset of C. jejuni strains was investigated. Comparative genome hybridization indicated that C. jejuni Mu-like prophage integrated element 1 (CJIE1) was more abundant in nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strains than in naturally transformable strains. Analysis of CJIE1 indicated the presence of dns (CJE0256), which is annotated as a gene encoding an extracellular DNase. DNase assays using a defined dns mutant and a dns-negative strain expressing Dns from a plasmid indicated that Dns is an endogenous DNase. The DNA-hydrolyzing activity directly correlated with the natural transformability of the knockout mutant and the dns-negative strain expressing Dns from a plasmid. Analysis of a broader set of strains indicated that the majority of nonnaturally transformable strains expressed DNase activity, while all naturally competent strains lacked this activity. The inhibition of natural transformation in C. jejuni via endogenous DNase activity may contribute to the formation of stable lineages in the C. jejuni population.

Bacterial populations of a single species often display considerable genetic diversity that supposedly aids their adaptation and survival in changing environments. One mechanism that contributes to the genetic diversity is horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (12). This process involves the assimilation of acquired genetic material. Many bacterial species have evolved sophisticated systems to enable the uptake of exogenous DNA, allowing natural transformation (6, 45). The mechanism of uptake of DNA differs among species but typically involves binding of double-stranded DNA to components of the cell surface, processing, and transport through the cytoplasmic membrane (6, 7, 11). For formation of the DNA uptake apparatus, different species use related proteins. These proteins have similarity with proteins involved in pilus assembly and secretion system formation. On arrival at the cytoplasmic membrane, only one of the DNA strands is transported into the cytoplasm and can be integrated into the bacterial genome, whereas the complementary strand is degraded into nucleotides (7).

One bacterial species that is naturally competent for DNA uptake is Campylobacter jejuni, the most common cause of bacterial gastroenteritis in humans in industrialized countries (4). Genetic typing indicates that there is great genetic diversity among C. jejuni strains (10, 47, 50). Multilocus sequence typing suggests that C. jejuni has a weakly clonal population structure and that HGT is common in this species (9, 41). Direct experimental evidence of the occurrence of HGT and the generation of genetic diversity in vivo was obtained from experiments with chickens infected with two C. jejuni strains carrying distinct genetic markers (8). However, genetic typing also indicates that stable lineages of C. jejuni exist and thus that not every strain in the C. jejuni population is able to acquire foreign DNA (20, 29, 34, 48).

The molecular basis for the apparent existence of clonal lineages of C. jejuni is not known. Thus far, the C. jejuni genes galE, dprA, and Cj0011c have been implicated in the process of natural transformation, particularly in the binding of DNA (16, 23, 43). For DNA uptake, the type II secretion system is important as type II secretion system-deficient mutants show a drastic decrease in the frequency of natural transformation (51). In some C. jejuni strains, a type IV secretion system may contribute to this process (2, 26). After arrival in the cytoplasm, the acquired DNA is integrated into the genome of C. jejuni via RecA-dependent homologous recombination (18). Lastly, it has been shown that N-linked protein glycosylation is required for full competence of C. jejuni (26). Thus far, the many steps involved in the natural transformation of C. jejuni and the variation in this process between strains have made it difficult to decipher the cause of the preservation of stable lineages in the C. jejuni population.

In the present study, we attempted to unravel the basis of the clonal behavior of distinct C. jejuni strains using a comparative whole-genomic approach. Systematic analysis of DNA microarrays probed with DNA of naturally transformable and nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strains resulted in the identification of a gene (dns) whose presence was strongly linked to a lack of natural competence. Inactivation of this gene in a clonal, nonnaturally transformable strain restored competence, while introduction of an intact copy of the gene into a transformable strain resulted in reduced transformability. Functional analysis revealed that the dns gene encodes a DNase that inhibits natural transformation through hydrolysis of exogenous DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study and their natural transformability are shown in Table 1. The natural transformation frequencies of these strains were analyzed using homologous pUOA13 plasmid DNA (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The lowest detectable level of the natural transformation frequency (10−10) is based on a minimum of one colony per plate. C. jejuni strains were cultured on heart infusion (HI) agar (Difco) supplemented with 5% sheep blood (HIS plates) or on blood agar base no. 2 medium (Oxoid) containing 4% sheep blood lysed with 0.7% saponin (Sigma) (saponin plates). C. jejuni was incubated at 37°C for 48 h under microaerobic conditions (6% O2, 7% CO2, 7% H2, and 80% N2) created with an Anoxomat system (Mart Microbiology, Drachten, The Netherlands). Escherichia coli was grown on Luria-Bertani agar or in Luria-Bertani broth at 37°C under aerobic conditions. When appropriate, media were supplemented with chloramphenicol (12.5 μg ml−1), kanamycin (30 μg ml−1), or ampicillin (100 μg ml−1).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Penner serotype | Genotype | Natural transformabilitya | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. jejuni wild-type strains | ||||

| C019165 | HS:1 | Nontransformable | J. A. Frost | |

| C013199 | HS:1 | Transformable | J. A. Frost | |

| C011338 | HS:1 | Transformable | J. A. Frost | |

| C017289 | HS:1 | Nontransformable | J. A. Frost | |

| C011672 | HS:1 | Nontransformable | J. A. Frost | |

| C019168 | HS:1 | transformable | J. A. Frost | |

| C011300 | HS:1 | Nontransformable | J. A. Frost | |

| C013500 | HS:2 | Transformable | J. A. Frost | |

| C356 (CNET076) | HS:2 | Nontransformable | W. F. Jacobs-Reitsma | |

| C012599 | HS:2 | Nontransformable | J. A. Frost | |

| 5003 (CNET002) | HS:2 | Transformable | S. L. On | |

| C012446 | HS:2 | Nontransformable | J. A. Frost | |

| D3468 | HS:19 | Nontransformable | 31 | |

| D3141 | HS:19 | Nontransformable | 31 | |

| CCUG10950 | HS:19 | Nontransformable | Culture Collection, University of Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden | |

| GB18 | HS:19 | Transformable | 13 | |

| D3226 | HS:19 | Nontransformable | 31 | |

| 233.95 | HS:41 | Nontransformable | 48 | |

| 308.95 | HS:41 | Nontransformable | A. J. Lastovica | |

| 21.97 | HS:41 | Nontransformable | A. J. Lastovica | |

| 386.96 | HS:41 | Nontransformable | 48 | |

| 260.94 | HS:41 | Nontransformable | 48 | |

| 41239B (CNET005) | HS:55 | Nontransformable | 20 | |

| 07479 | HS:55 | Nontransformable | 20 | |

| 12795850312 | HS:55 | Nontransformable | D. L. Baggesen | |

| 40707L (CNET007) | HS:55 | Nontransformable | 20 | |

| NCTC 11168-O | HS:2 | Transformable | 17 | |

| RM1221 | HS:53 | Nontransformable | 30 | |

| C. jejuni mutant strain and transformants | ||||

| C356dns::cat | This study | |||

| CNET002(pWM1007Pr1492dns) | This study | |||

| CNET002(pWM1007Pr1492) | This study | |||

| E. coli strains | ||||

| DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rk− mk+) phoA supE44 λ−thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Invitrogen, Breda, The Netherlands | ||

| K12 ER2925 | ara-14 leuB6 fhuA31 lacY1 tsx78 glnV44 galK2 galT22 mcrA dcm-6 hisG4 rfbD1 R(zgb210::Tn10)TetsendA1 rpsL136 dam13::Tn9 xylA-5 mtl-1 thi-1 mcrB1 hsdR2 | NEB, Ipswich, MA |

The lowest level of detection for the natural transformation frequency is 10−10. For natural transformation frequencies see Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Construction of the C. jejuni microarray.

DNA fragments of individual open reading frames (ORFs) were amplified by using the Sigma-7 Genosys (The Woodlands, TX) C. jejuni ORFmer primer set specific for strain NCTC 11168 coding sequences and by using primers from Operon Technologies (Alameda, CA) specific for unique sequences of strain RM1221, as previously described (35). A total of 1,530 and 227 PCR products were amplified from strain NCTC 11168 and strain RM1221, respectively. The PCR products were purified with a Qiagen 8000 robot by using a QIAquick 96-well Biorobot kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and spotted in duplicate onto Ultra-GAPS glass slides (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) by using an OmniGrid Accent 17 (GeneMachines, Ann Arbor, MI), as described previously (35). Immediately after printing, the microarrays were UV cross-linked at 300 mJ by using a Stratalinker 1800 UV cross-linker (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and stored in a desiccator. Before use, microarrays were blocked with Pronto! prehybridization solution (Corning Inc.) used according to the manufacturer's specifications.

Isolation and fluorescent labeling of chromosomal DNA.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from C. jejuni using a Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, BIOzymTC, Landgraaf, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's protocol for gram-negative bacteria. For each hybridization reaction reference DNA (equal amounts of chromosomal DNA isolated from C. jejuni strains NCTC 11168-O and RM1221) was labeled with indodicarbocyanine (Cy5)-dUTP (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), and DNA isolated from the test strain was labeled with indocarbocyanine (Cy3)-dUTP (GE Healthcare). For each labeling reaction 2 μg of chromosomal DNA was mixed with 5 μl of 10× NEBlot labeling buffer (New England Biolabs [NEB], Ipswich, MA) and water to obtain a final volume of 41 μl. This mixture was incubated at 95°C for 5 min and then at 4°C for 5 min. When the mixture was cool, the other components of the labeling reaction were added, namely, 5 μl of a 10× deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture (1.2 mM each of dATP, dCTP, and dGTP and 0.5 mM dTTP; Promega Corporation, Madison, WI), 3 μl of Cy3-dUTP (1 mM) or Cy5-dUTP (1 mM), and 1 μl Klenow fragment (5 U; NEB). After 16 h of incubation at 37°C, the labeled DNA was purified using a Qiagen QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After purification, the labeled reference DNA and test DNA were mixed and dried with a vacuum.

Microarray hybridization.

Hybridization reactions were performed in duplicate for each test strain. Labeled DNA was dissolved in 47 μl of Pronto! cDNA hybridization solution (Corning Inc.) and incubated at 95°C for 5 min. For each hybridization reaction 15 μl of this mixture was put onto a microarray slide. The slide was sealed with a coverslip and placed in a hybridization chamber (Corning Inc.). After incubation at 42°C for 16 h, the slide was rinsed twice with wash solution I (2× saline sodium citrate [SSC], 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate]) at 42°C for 10 min, which was followed by two rinses with wash solution II (1× SSC) at room temperature for 10 min and two rinses with wash solution III (0.1× SSC) at room temperature for 10 min. The microarray slide was dried by centrifugation (10 min, 300 × g).

Microarray data analysis.

Two independent microarray analyses were performed for each strain. Microarrays were scanned and analyzed as previously described (35). Generally, DNA microarrays were scanned using an Axon GenePix 4000B microarray laser scanner (Axon Instruments, Inc., Union City, CA). Features and the local background intensities were detected and quantified with GenePix 4.0 software (Axon Instruments, Inc.). Poor features were excluded from further analysis if they contained abnormalities or were within regions with nonspecific fluorescent background. The data were filtered so that spots with a reference signal less than the background signal plus three standard deviations of the background signal were discarded. Signal intensities were corrected by subtracting the local background, and then the Cy5/Cy3 (test/reference) ratios were calculated. To compensate for unequal dye incorporation, data normalization was performed as described previously (1, 35). The NCTC 11168 and RM1221 strain-specific spots hybridized to only-half of the reference DNA (the Cy5-labeled mixture of NCTC 11168-O and RM1221 DNA), increasing the Cy3/Cy5 ratio twofold. The ratios for these spots were therefore divided by two before the status of the gene was determined. The ratios for spots for each individual gene were then averaged. As previously described (35), the comparative genomic indexing analysis defined the status of a gene as present when the Cy3/Cy5 intensity ratio was >0.6, as divergent when the Cy3/Cy5 intensity ratio was between 0.6 and 0.3, and as absent when the Cy3/Cy5 intensity ratio was <0.3. The presence, divergence, and absence status data for all genes were converted into trinary scores (2, present; 1, divergent; 0, absent). The trinary gene scores for each replicate for all strains were analyzed further with GeneSpring microarray analysis software, version 7.3 (Agilent Technologies, Redwood City, CA), and subjected to average-linkage hierarchical clustering with the standard correlation and bootstrapping. The comparative genomic indexing analysis to assign present and absent genes of the C. jejuni strains was further verified using the GENCOM software (36, 37). For each of these hybridizations, the Cy5 and Cy3 signal intensities were corrected by subtracting the local background before submission to the GENCOM program for determination of the presence or absence assignments for each gene.

Electrotransformation of C. jejuni.

C. jejuni strains that are not naturally competent can be forced to accept DNA by using electrotransformation. This approach allowed us to generate transformants using plasmid (or chromosomal) DNA from different sources and for various purposes, including introduction of resistance markers, generation of knockout mutants, or introduction of resistance markers on replicating plasmids. Electrotransformation of C. jejuni was carried out essentially as described previously (49). In brief, electrocompetent bacteria were prepared from C. jejuni grown on HIS plates for 16 h. The bacteria were harvested and washed four times with 15% glycerol-272 mM sucrose (4°C). Finally, the suspension was adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm of 80. Aliquots (50 μl) were stored at −80°C. For electrotransformation 5 μl of isolated plasmid DNA was added to 50 μl of electrocompetent bacteria. The mixture was transferred to a 0.2-cm Gene Pulser cuvette (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and pulsed (2.48 kV, 25 μF, 600 Ω) with a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad). After electroporation the bacteria were allowed to recover on nonselective saponin plates for 4 h at 37°C under microaerobic conditions. After recovery, the bacteria were harvested and plated onto selective saponin plates.

Construction of a dns knockout strain.

The dns gene (CJE0256) was amplified from the chromosome of C. jejuni RM1221 using primers dns-F and dns-R (Table 2) and a Taq polymerase with proofreading. The PCR product (672 bp) was cloned into the cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Breda, The Netherlands), resulting in plasmid pdns. Subsequently, the complete pdns plasmid (4.6 kb) was amplified with primers dnsSacII and dnsMfeI (Table 2) to introduce SacII and MfeI restriction sites in the dns coding sequence. Next, primers catSacII and catMfeI (Table 2) were used to generate a 1,038-bp PCR product containing the Campylobacter coli cat gene (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase; Cmr) from pUOA23. Both PCR products were digested with SacII and MfeI to allow insertion of the cat gene into dns. The resulting knockout construct, pdns::cat (5.6 kb), was introduced into dns+ C. jejuni strain C356 via electrotransformation, resulting in C356dns::cat. Integration into the chromosome was verified by PCR using chromosomal DNA as the template with primers dnscontr-F and dnscontr-R. These primers are complementary to sequences of the disrupted dns gene upstream and downstream of the cat insert (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Primers and plasmids used in this study

| Primer or plasmid | Sequence (5′-3′) or relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Primers | ||

| dns-F | ATGAAAAAAATAATAAGCGTTTTAATAC | |

| dns-R | TTAGAGTAATGCTCTAATTCTTTTTTC | |

| dnsSacII | CATATGCCGCGGGGCTCCTACTAATTTAAAATATAC | |

| dnsMfeI | GTCGACCAATTGTCAGCATATCTAAAATTGCTTCTATC | |

| catSacII | CATATGCCGCGGCACAACGCCGGAAACAAG | |

| catMfeI | GTCGACCAATTGCCGCAGGACGCACTACTCT | |

| dnscontr-F | CTTTTAAGATTTCTCGTTTGTCG | |

| dnscontr-R | CAAGCCTTGAAATAATGCATAATG | |

| dnsexpr-F | AGATCTTCTAGATAAAAAATAAAAAGGAGAATAAATG | |

| dnsexpr-R | CCATGGCAATTGTTAGAGTAATGCTCTAATTC | |

| Pr1492MfeI | ACTAGTCAATTGGCGATGGCCCTG | |

| Pr1492XbaI | AGATCTTCTAGACTCATTTAACGGTTGTCTCC | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1 | TA cloning vector, Ampr | Invitrogen |

| pdns | pCR2.1 containing the dns gene of C. jejuni strain RM1221 | This study |

| pUOA23 | E. coli-C. jejuni shuttle vector containing the cat gene of C. coli, Cmr | |

| pdns::cat | pdns with cat inserted in dns, Cmr | This study |

| pWM1007Pr1492 | C. jejuni expression plasmid containing the Cj1492 promoter, Kmr | 52 |

| pWM1007Pr1492dns | C. jejuni expression plasmid with dns | This study |

| pUOA13 | E. coli-C. jejuni shuttle vector, Kmr | 46 |

The endonuclease restriction sites introduced into the sequences are underlined.

Construction of the expression plasmid carrying Dns.

To construct a dns expression plasmid, the dns gene (CJE0256) along with 22 bp of its 5′ flanking region was amplified from chromosomal DNA of C. jejuni RM1221 using primers dnsexpr-F and dnsexpr-R (Table 2), which introduced XbaI and MfeI restriction sites. To introduce the same restriction sites into the kanamycin-resistant expression plasmid pWM1007Pr1492 (52), a PCR product was generated using primers Pr1492MfeI and Pr1492XbaI (Table 2). After digestion with XbaI and MfeI, dns (704 bp) was ligated into pWM1007Pr1492 (10.6 kb) to form pWM1007Pr1492dns (11.3 kb). The resulting C. jejuni Dns expression plasmid was electrotransformed into the dns-negative C. jejuni strain CNET002, resulting in CNET002(pWM1007Pr1492dns).

Natural transformation frequency of C. jejuni.

For natural transformation of C. jejuni, the biphasic method was used (46). In brief, C. jejuni grown for 16 h on HIS plates was harvested in HI broth (optical density at 600 nm, 1.0), and 200 μl of the suspension was added to a 5-ml polystyrene tube containing 2 ml of HI agar. After 3 h of incubation at 37°C under microaerobic conditions, 2 μg of a homologous plasmid (pUOA13; Kmr) or homologous chromosomal DNA isolated from strains containing a chloramphenicol resistance cassette in hipO (i.e., homologous to the recipient strain) was added. For each strain the type of DNA used was dependent on the availability and combination of antibiotic resistance markers. After additional incubation (3 h, 37°C) under microaerobic conditions, the bacteria were harvested from the polystyrene tube and collected by centrifugation (3,300 × g, 8 min). The pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of HI broth. For determination of natural transformation frequencies, the number of CFU ml−1 was calculated using the track dilution technique (24), in which 10-μl portions of serial dilutions (10−5 to 10−8) were spotted onto nonselective saponin plates. To determine the number of transformants per ml, 200-μl portions of the appropriate serial dilutions were plated onto selective saponin plates. After incubation at 37°C, the numbers of colonies present on the plates were determined. The natural transformation frequency was calculated by dividing the number of transformants ml−1 (selective plates) by the total number of bacteria ml−1 (nonselective plates). The resulting natural transformation frequency specified the fraction of bacteria that acquired a resistance marker.

DNase assay.

For measurement of DNase activity, C. jejuni was grown in 200 ml of HI broth under microaerobic conditions (16 h, 37°C, 160 rpm) and used to isolate fractions enriched for periplasmic proteins, as described previously (25). Protein concentrations of the fractions were determined using Coomassie Plus protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For the DNase assay a 30-μl reaction mixture containing 500 ng of lambda DNA (500 μg ml−1; NEB), 2 μl of 100 mM MgCl2, and 1 μg of protein from enriched fractions was assembled. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, 6 μl of 6× blue/orange loading dye (Promega Benelux BV, Leiden, The Netherlands) was added, and DNase activity was analyzed by electrophoresis using a 0.8% agarose gel.

RESULTS

Hierarchical clustering of C. jejuni strains by comparative genome hybridization.

In the search for differences in genome content between naturally transformable and nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strains, comparative genome hybridization was used. A multistrain C. jejuni microarray was designed that comprised PCR fragments of 1,530 ORFs (94%) of the naturally transformable strain NCTC 11168 and 227 unique ORFs of the nonnaturally transformable strain RM1221. During validation of this microarray by Parker et al. (35), the chromosomal DNA of strains NCTC 11168 and RM1221 hybridized equally well to the ORFs common to both strains, and the results also correlated with the results of sequence analysis. In the present study, the array was hybridized with chromosomal DNA isolated from six naturally transformable and 20 nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strains, as well as control strains NCTC 11168-O (naturally transformable) and RM1221 (nonnaturally transformable). Of the naturally transformable strains, five were Penner serotype HS:1 or HS:2 strains, while one was an HS:19 strain. The 20 nonnaturally transformable strains belonged to Penner serotypes HS:1, HS:2, HS:19, HS:41, and HS:55 (Table 1). The hybridization data obtained were analyzed, and the status of a gene (present, absent, or divergent) was defined using comparative genomic indexing. This served as a basis for hierarchical clustering of the strains.

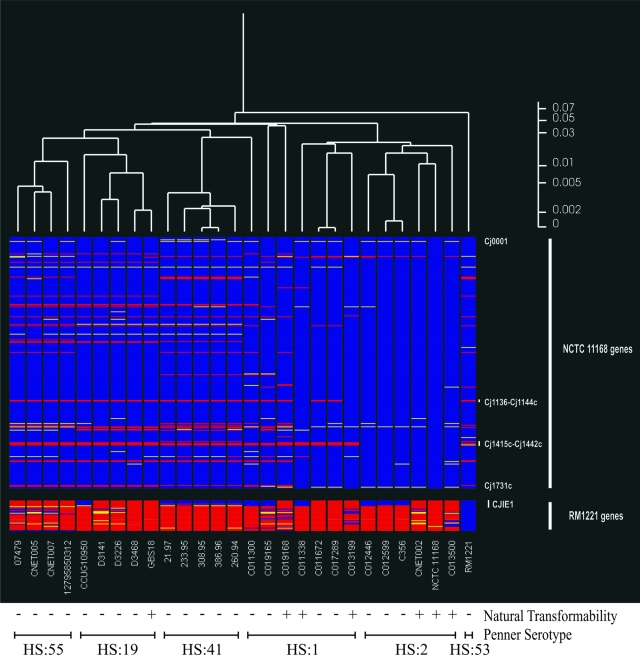

As shown in Fig. 1, distinct clusters were formed by strains belonging to Penner serotypes HS:55, HS:19, HS:41, and HS:2, while the HS:1 strains were not located in a single cluster. Based on the distance scores, the genetic diversity within the Penner HS:41 cluster (all South African isolates) was less than that within the clusters formed by the HS:55, HS:19, and HS:2 strains. No difference in the level of diversity between these clusters was noted. The HS:1 strains were the most diverse subset of strains used in this study. As in this analysis the naturally transformable and nonnaturally transformable strains did not appear to be distinct clusters, no indication of genes that are restricted to one of these phenotypes was obtained.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of C. jejuni strains by cluster analysis of comparative genomic indexing results. The genes are presented in the order of their positions on the genome of C. jejuni NCTC 11168 and are followed by the genes of C. jejuni RM1221 that are absent from C. jejuni NCTC 11168. For frames of reference, the lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis locus (Cj1136-Cj1144c) and the capsular biosynthesis locus (Cj1415c-Cj1442c) from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 are indicated. The Mu-like prophage insertion element (CJIE1) from C. jejuni RM1221 is also indicated. The gene status is color coded as follows: blue, present; yellow, variable or unknown; red, absent; gray, no data. For cutoffs for absence and presence predictions, see Materials and Methods. An average linkage hierarchical clustering of the C. jejuni strains was compiled in GeneSpring, version 7.3, from the comparative genome hybridization data for each element with the standard correlation and bootstrapping. A scale for distance scores is on the right.

C. jejuni competence genes.

Closer inspection of the hybridization data indicated that all the chromosomal genes thus far implicated in the process of natural transformation in C. jejuni were present in the 26 strains analyzed (Table 3). To identify novel genes thus far not associated with natural transformation, the hybridization data were screened for genes present in ≥50% of the naturally transformable strains and absent in ≥50% of the nonnaturally transformable strains. A total of 64 genes were present in the majority (67% to 100%) of the naturally transformable strains and absent in more than one-half (50% to 80%) of the nonnaturally transformable strains (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Fifty-nine of these genes are located in intraspecies hypervariable regions 1, 6 to 14, and 16 of the C. jejuni genome (35, 42). In a second analysis the hybridization data were screened for genes absent in ≥50% of the naturally transformable strains and present in ≥50% of the nonnaturally transformable strains. A total of 37 genes were absent in most (67% to 83%) of the naturally transformable strains and present in more than one-half (55% to 90%) of the nonnaturally transformable strains (Table 4). Five of these genes are located in intraspecies hypervariable regions 13, 14, and 17 of the C. jejuni genome (35), but the majority (32 genes) hybridized with genes of C. jejuni integrated element 1 (CJIE1) present in C. jejuni strain RM1221 (15).

TABLE 3.

C. jejuni natural competence and transformation genes

| Locus tag | Gene | Protein | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cj0011c | Putative nonspecific DNA binding protein | 23 | |

| Cj0634 | dprA | SMF family protein | 43 |

| Cj0825 | Putative processing peptidase | 51 | |

| Cj1028c | Possible purine/pyrimidine phosphoribosyltransferase (ctsW) | 51 | |

| Cj1076 | proC | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase | 51 |

| Cj1077 | ctsT | Putative periplasmic protein | 51 |

| Cj1131c | galE | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | 16 |

| Cj1343c | Putative periplasmic protein (ctsG) | 51 | |

| Cj1352 | ceuB | Enterochelin uptake permease | 51 |

| Cj1470c | Pseudogene (type II protein secretion system F protein) (ctsF) | 51 | |

| Cj1471c | ctsE | Putative type II protein secretion system E protein | 51 |

| Cj1472c | Hypothetical protein (ctsX) | 51 | |

| Cj1473c | ctsP | Putative ATP/GTP-binding protein | 51 |

| Cj1474c | ctsD | Putative type II protein secretion system D protein | 51 |

| Cj1475c | ctsR | Hypothetical protein | 51 |

TABLE 4.

Genes absent in at least 67% of the naturally transformable C. jejuni strains and present in the majority (≥55%) of nonnaturally transformable strains

| Region | Locus tag | Product | Locus | Presence in C. jejuni strains

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naturally transformable

|

Nonnaturally transformable

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Penner serotype HS:1

|

Penner serotype HS:2

|

Penner serotype HS:19

|

Penner serotype HS:1

|

Penner serotype HS:2

|

Penner serotype HS:19

|

Penner serotype HS:41

|

Penner serotype HS:55

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| C013199 | C011338 | C019168 | C013500 | 5003 (CNET002) | GB18 | C011300 | C017289 | C019165 | C011672 | C012446 | C012599 | C356 (CNET076) | D3141 | D3226 | CCUG10950 | D3468 | 21.97 | 233.95 | 260.94 | 308.95 | 386.96 | 40707L (CNET007) | 07479 | 12795850312 | 41239B (CNET005) | ||||

| CJIE1a | CJE0215 | Phage repressor protein, putative | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| CJE0220 | Adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase | dam | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | |

| CJE0221 | Phage virion morphogenesis protein, putative | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0226 | Phage-related tail protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0227 | Tail sheath protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0228 | Hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0230 | Hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0231 | Putative phage tail fiber protein H | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0232 | Putative phage tail protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0233 | Baseplate assembly protein J, putative | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0234 | Baseplate assembly protein W, putative | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0236 | Baseplate assembly protein V, putative | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0237 | Conserved hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | ||

| CJE0241 | Conserved hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0243 | Hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0244 | Mu-like prophage I protein, putative | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | ||

| CJE0245 | Hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0246 | Conserved hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0247 | Conserved domain protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0248 | Hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0249 | Phage uncharacterized protein, C-terminal domain, putative | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0250 | Hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0252 | Putative tail-related phage protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0254 | Tail protein D, putative | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0256 | Extracellular DNase | dns | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | |

| CJE0257 | Conserved domain protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0258 | Conserved domain protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0259 | Hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0261 | Hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | ||

| CJE0265 | Host nuclease inhibitor protein Gam, putative | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0266 | Conserved hypothetical protein | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| CJE0269 | Bacteriophage DNA transposition protein B, putative | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| Variable region 17b | CJE0310 | Adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | |

| Variable region 14c | CJE1725 | 4-Carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase, putative | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| CJE1727 | Conserved hypothetical protein | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| CJE1728 | Transporter, putative | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Variable region 13d | Cj1442c | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

Identification of a DNase-encoding gene.

Because of the remarkable difference in occurrence of CJIE1 genes between naturally transformable and nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strains, CJIE1 was studied in more detail. CJIE1 encodes several proteins with similarity to bacteriophage Mu and Mu-like prophage proteins (15, 32). Of the 32 CJIE1 genes of interest for this study, 16 are annotated as genes encoding phage-related proteins, 12 are annotated as genes encoding hypothetical proteins, and 3 are annotated as genes encoding conserved domain proteins (Table 4). The remaining gene has been annotated as a gene encoding an extracellular DNase (CJE0256; dns) on the basis of its similarity at the protein level with dns from Aeromonas hydrophila. The translated sequence of dns from C. jejuni strain RM1221 contains a domain typical of endonuclease I proteins, which are bacterial secreted or periplasmic endonucleases. In agreement with this is the prediction of a signal peptide cleavage site in the amino acid sequence of Dns (SignalP 3.0) (3).

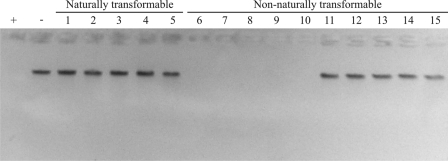

To investigate the function of Dns in more detail, several mutant strains were constructed using electrotransformation (see Materials and Methods). The dns gene was inactivated in the nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strain C356 via insertion of a chloramphenicol resistance cassette. The inactivated gene located on a suicide plasmid was introduced into strain C356 by electrotransformation, yielding the dns knockout mutant C356dns::cat. Transformants carried the inactivated gene in their genomes, indicating that the process of recombination was functional in this nonnaturally transformable strain. The function of Dns was then assessed by a DNase assay in which the ability of the strains to hydrolyze phage lambda DNA was determined. As shown in Fig. 2, the dns+ C356 wild-type strain hydrolyzed DNA (lane 1). This activity was not observed for C356dns::cat (Fig. 2, lane 2). These results suggest that Dns indeed is critical for C. jejuni endonuclease activity.

FIG. 2.

Determination of the DNase activity of a C. jejuni dns knockout mutant (C356dns::cat) and a Dns expression construct [CNET002(pWM1007Pr1492dns)]. Phage lambda DNA (500 ng) was incubated (1 h, 37°C) with fractions isolated from C. jejuni and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Lane 1, nonnaturally transformable dns-positive strain C356; lane 2, dns knockout strain C356dns::cat; lane 3, naturally transformable strain CNET002; lane 4, CNET002 with Dns expression construct [CNET002(pWM1007Pr1492dns)]; lane 5, CNET002 containing the empty expression plasmid [CNET002(pWM1007Pr1492)]; lane +, positive control (DNA treated with 1 μg DNase I); lane −, negative control (mock-treated DNA).

Since the availability and possible combinations of antibiotic resistance markers did not allow us to complement inactivated dns in strain C356dns::cat, we introduced dns of RM1221 into the naturally transformable dns-negative C. jejuni strain CNET002. This gene was placed on expression plasmid pWM1007Pr1492, which was introduced by electrotransformation into strain CNET002. As a control, the same vector but without the insert was introduced into this strain. Analysis of isolated fractions of the different strains for DNase activity indicated the presence of DNA-hydrolyzing activity for the strain with the dns+ plasmid (Fig. 2, lane 4) but not for the parental strain or the control strain possessing the expression plasmid without the insert (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 5).

Inhibition of natural transformation by Dns.

To investigate the effect of Dns activity on the process of natural transformation, we determined the natural transformation frequencies for the dns+ strain C356 and its dns mutant derivative C356dns::cat, using the biphasic method of natural transformation (Table 5). The potential effect of restriction-modification systems was avoided by using homologous plasmid DNA which conferred kanamycin resistance. While parental strain C356 yielded no kanamycin-resistant transformants, inactivation of dns in C356dns::cat resulted in a change of phenotype from nonnaturally transformable to naturally transformable with a natural transformation frequency of (2.4 ± 0.6) × 10−6 (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Effect of Dns on natural transformation frequencies of C. jejuni

| Straina | Natural transformation frequencyb |

|---|---|

| C356 | − |

| C356dns::cat | (2.4 ± 0.6) × 10−06c |

| CNET002 | (2.5 ± 0.2) × 10−05 |

| CNET002(pWM1007Pr1492) | (2.7 ± 1.4) × 10−05 |

| CNET002(pWM1007Pr1492dns) | (2.1 ± 1.8) × 10−08c |

To determine the natural transformation frequency of C. jejuni strains C356 and C356dns::cat, homologous pUOA13 plasmid DNA (kanamycin resistance marker) was used; for strains CNET002, CNET002(pWM1007Pr1492), and CNET002(pWM1007Pr1492dns) homologous chromosomal DNA was used (chloramphenicol resistance marker).

The natural transformation frequency was determined by dividing the number of transformants ml−1 by the total number of CFU per ml−1. The values are the averages of three experiments. −, below the detection limit (5.6 × 10−10 ± 5.0 × 10−10), which is based on a minimum of one colony per plate, adapted to the volumes used in the procedure.

P < 0.05 (Student's t test) for a comparison with the corresponding parental strain.

Natural transformation frequencies were also determined for the dns-negative C. jejuni wild-type strain CNET002 and its derivatives carrying the expression plasmid pWM1007Pr1492 with or without the dns gene, using homologous chromosomal DNA as a donor (CNET002hipO::cat). The donor DNA used contains a chloramphenicol resistance marker obtained through electrotransformation with the suicide plasmid pHipO::cat (8). In this experiment, expression of Dns in the naturally transformable strain CNET002 caused a 3-log reduction in the natural transformation frequency compared to that of the parental control strains (Table 5). No reduction in natural transformation frequency was observed for strain CNET002 that contained the empty expression vector. Altogether, these results indicate that the presence of Dns impairs natural transformation in C. jejuni.

Prevalence of DNase activity in naturally transformable and nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strains.

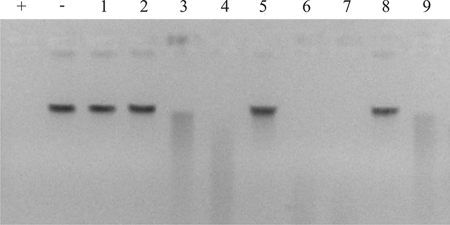

To assess the broader importance of Dns as a determining factor of natural transformation in C. jejuni, we determined the DNase activity for a set of naturally transformable strains. None of the naturally transformable strains hydrolyzed DNA (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 5). One of the strains (C011338) does contain dns, but sequence analysis and comparison with the RM1221 dns sequence revealed a point mutation in the start codon (ATG → ATA), which is probably responsible for the absence of DNase activity in C011338.

FIG. 3.

Determination of the DNase activity of naturally transformable C. jejuni strains and dns-positive nonnaturally transformable strains. DNase activity was assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Fractions were isolated from naturally transformable C. jejuni strains C013199, C011338, C019168, C013500, and GB18 (lanes 1 to 5, respectively) and from dns-positive nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strains C011300, C019165, C012446, C012599, CCUG10950, 21.97, 233.95, 260.94, 308.95, and 386.95 (lanes 6 to 15, respectively). Lane +, positive control (DNA treated with 1 μg DNase I); lane −, negative control (mock-treated DNA).

All of the tested nonnaturally transformable dns+ strains displayed DNase activity (Fig. 3, lanes 6 to 10), except the five strains belonging to Penner serotype HS:41 (lanes 11 to 15). Reverse transcription-PCR analysis indicated that dns is transcribed in these strains (data not shown). However, alignment of the dns sequence (locus tag CJJ26094_0510) from Penner HS:41 strain 260.94 with the dns sequence from strain RM1221 revealed nine point mutations, resulting in four amino acid substitutions (e.g., a C → Y substitution), which may explain the lack of DNase activity.

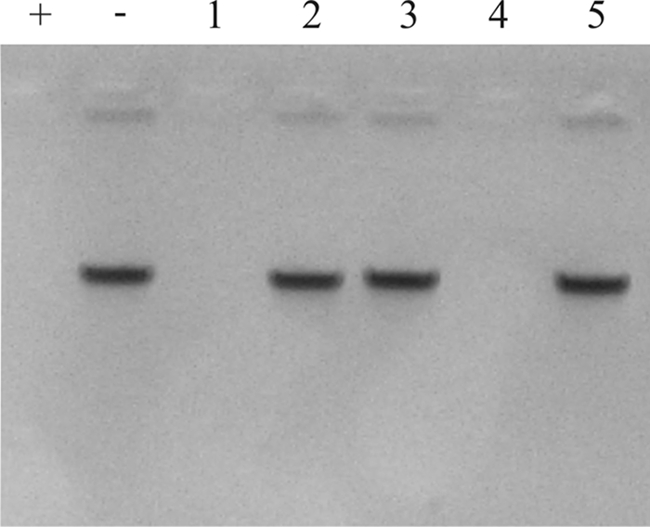

Analysis of the nonnaturally transformable dns-negative strains for the presence of DNA-hydrolyzing activity revealed DNase activity for five of the nine nonnaturally transformable dns-negative strains (Fig,. 4, lanes 3, 4, 6, 7, and 9). This indicates that a different, as-yet-undefined DNase is present in a subset of the dns-negative strains, which may account for the nonnatural transformability of these strains. These results underpin the importance of DNase activity as a major determinant of natural transformation of C. jejuni.

FIG. 4.

Determination of the DNase activity of nonnaturally transformable dns-negative C. jejuni strains. DNase activity was assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The nonnaturally transformable dns-negative strains tested were C017289, C011672, D3141, D3226, D3468, CNET007, 07479, 12795850312, and CNET005 (lanes 1 to 9, respectively). Lane +, positive control (DNA treated with 1 μg DNase I); lane −, negative control (mock-treated DNA).

DISCUSSION

C. jejuni is one of the bacterial species which are known to be naturally competent (28). Naturally transformable C. jejuni strains are able to acquire DNA from the environment and integrate this genetic material into their genomes. A subset of C. jejuni strains, however, appears to be deficient in natural transformation. The present study provides evidence that 11 of 20 strains that are naturally transformation deficient express DNase activity. Genetic transfer of the identified dns gene, which encodes DNase activity, to a naturally transformable strain results in strongly reduced natural transformability. Conversely, inactivation of the gene in a nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strain renders the strain competent for natural transformation. These results, for the first time, provide a genetic basis for the lack of natural transformation of C. jejuni strains and provide the opportunity to manipulate the system to our benefit. The presence of DNase activity may contribute to the appearance of subsets of C. jejuni strains as stable lineages in genetic typing studies.

Our strategy to discover determinants of natural transformation involved comparative genome hybridization using whole-genome ORF-based DNA arrays. This approach initially resulted in genomic clustering of the investigated strains only according to Penner serotype rather than according to competence for natural transformation (Fig. 1). The formation of clusters for the Penner HS:19, HS:41, and HS:55 strains is in agreement with the results obtained by other workers (20, 34, 48). Specific analysis of the hybridization data for the absence or presence of previously identified genes involved in natural transformation of C. jejuni (16, 23, 43, 51) also did not discriminate between the tested naturally transformable and nonnaturally transformable strains; all chromosomally located competence genes identified so far (Table 3) appeared to be present in all strains tested. The functionality of these genes could obviously not be established from the results of the DNA array analysis.

Clear genetic differences between the sets of naturally transformable and nonnaturally transformable strains were observed when the hybridization data sets were analyzed on the basis of genes present in ≥50% of the naturally transformable strains and absent in ≥50% of the nonnaturally transformable strains and vice versa (Table 4; see Table S2 in the supplemental material). These settings yielded a remarkable distinction for the presence of CJIE1-encoded genes in nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strains compared to naturally transformable strains. CJIE1 is one of the four large integrated elements present in strain RM1221 but absent in strain NCTC 11168 (15). The majority of genes located on CJIE1 encode proteins with similarity to bacteriophage Mu and Mu-like prophage proteins (15, 32) or code for hypothetical proteins. However, one gene (dns; CJE0256) is annotated as a gene encoding an extracellular DNase. In our data sets dns was always found in combination with other CJIE1 genes.

At the protein level C. jejuni Dns displays considerable sequence similarity with other bacterial nucleases, e.g., Dns of Vibrio cholerae (14), EndA of E. coli (22), Dns of A. hydrophila (5), NucM of Erwinia chrysanthemi (33), and Vvn of Vibrio vulnificus (53). In addition, Dns of C. jejuni is predicted to contain a domain typical of endonuclease I proteins. In general, members of this class of enzymes hydrolyze DNA and are located in the periplasm or secreted into the environment. This corresponds with the prediction of a signal peptide cleavage site in Dns and the observation by Hänninen (19) that disruption of the Campylobacter cell envelope by polymyxin B treatment accelerates DNA hydrolysis. On the basis of these characteristics, we hypothesized that the Dns protein may act as an inhibitor of natural transformation in C. jejuni.

Functional evidence that the identified dns gene encodes DNase activity was obtained from DNase assays performed with a genetically defined dns knockout mutant and a C. jejuni strain in which Dns of RM1221 was expressed from a plasmid (Fig. 2). Natural transformation assays with these strains further demonstrated that inactivation of dns in a nonnaturally transformable strain changed the phenotype into a naturally transformable phenotype and that the acquisition of DNase activity results in a strong reduction in natural transformability (Table 5). Homologous plasmid DNA and homologous chromosomal DNA were used to determine the natural transformability of these strains, depending on the availability of antibiotic resistance markers. In our hands naturally transformable strains can be naturally transformed with both homologous plasmid and chromosomal DNA, in contrast to nonnaturally transformable strains, suggesting that the system for natural transformation does not differentiate between plasmid and chromosomal DNA.

The significance of DNase activity as a cause of a lack of natural competence was further underpinned by the absence of DNase activity in all of the naturally transformable strains tested and the presence of DNase activity in more than one-half of the nonnaturally transformable C. jejuni strains, including a subset of strains that do not contain the dns gene (Fig. 3 and 4). The latter finding indicates that some strains contain another (unidentified) nuclease that may account for their apparent defect in natural transformation.

A special group of strains in our data set is the five Penner serotype HS:41 strains that were analyzed. These strains, all of which originate from South Africa, carry the CJIE1 element, including dns (Table 4). These strains are nonnaturally transformable but lack DNase activity (Fig. 3). This suggests that this group of strains may carry a defect elsewhere in the DNA transformation mechanism, similar to the group of nonnaturally transformable strains that show no DNase activity. Activity of restriction-modification systems is unlikely to be the cause of the lack of transformation as we used donor DNA derived from the homologous C. jejuni strain in the natural transformation assays. The cause of inactivity of Dns in these strains is not known. For Vvn, the Dns homologue of V. vulnificus, it is known that disulfide bridges are required for activity (53). The noted change of one cysteine residue to tyrosine in Dns of C. jejuni strain 260.94 could be responsible for the lack of DNase activity.

The presence of DNA-hydrolyzing activity in C. jejuni has previously been observed (21, 38) and is in fact one of the criteria for Lior's extended biotyping scheme for thermophilic campylobacters (27). Indeed, analysis of our set of strains with the Lior DNA hydrolysis biotyping method, using agar with 0.005% toluidine blue and a polymyxin B treatment (19), yielded results similar to those of our DNase assays (data not shown). The present identification of Dns in a subset of these strains provides for the first time a genetic basis for the DNA hydrolysis component of Lior's extended biotyping method. The presence of Dns may also explain the previously observed DNA hydrolysis activity present in some C. jejuni strains, although in that study no clear correlation was found between DNase activity and competence (46).

Although Dns inhibits natural transformation in C. jejuni, Dns+ strains could be transformed via electrotransformation. During electrotransformation bacteria are exposed to an electric field, resulting in the formation of transient pores in the membranes, through which DNA enters the cytoplasm (40). The pores are only short lived, implying that DNA that has reached the cytoplasm is briefly exposed to the periplasm and its nucleases. If DNA uptake takes more time during natural transformation, this may explain why nonnaturally transformable Dns+ strains can be electrotransformed.

The inhibition of natural transformation of C. jejuni through Dns likely affects the frequency of HGT within the species C. jejuni. The finding that the dns gene is located in the integration element CJIE1 may imply that insertion of this element may have contributed to the development of relatively stable clonal lineages. The strains may still acquire genes via conjugative plasmids that are present in some C. jejuni strains (39, 44). However, the presence of relatively stable genetic lineages suggests that under natural conditions this mode of gene transfer may be limited. In the laboratory, induction of loss of CJIE1 by, e.g., mitomycin C treatment (15) or targeted inactivation of dns, as used in the present study, may be a valuable new asset for restoring natural transformation in genetically poorly accessible strains, such as strain RM1221.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. A. Frost, W. F. Jacobs-Reitsma, S. L. On, M. J. Blaser, A. van Belkum, B. Duim, A. J. Lastovica, P. E. Carter, D. L. Baggesen, D. G. Newell, R. E. Mandrell, and D. E. Taylor for kindly supplying C. jejuni strains and vectors.

This work was supported by the Product Boards for Livestock, Meat, and Eggs (PVE), Zoetermeer, The Netherlands, and The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) (NWO-VIDI grant 917.66.330 to M.M.S.M.W. and a travel grant to E.J.G.). C.T.P. and M.R.G. were supported by United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service CRIS project 5325-42000-045.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 January 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anjum, M. F., S. Lucchini, A. Thompson, J. C. D. Hinton, and M. J. Woodward. 2003. Comparative genomic indexing reveals the phylogenomics of Escherichia coli pathogens. Infect. Immun. 714674-4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacon, D. J., R. A. Alm, D. H. Burr, L. Hu, D. J. Kopecko, C. P. Ewing, T. J. Trust, and P. Guerry. 2000. Involvement of a plasmid in virulence of Campylobacter jejuni 81-176. Infect. Immun. 684384-4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendtsen, J. D., H. Nielsen, G. von Heijne, and S. Brunak. 2004. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340783-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butzler, J. P. 2004. Campylobacter, from obscurity to celebrity. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10868-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, M. C., S. Y. Chang, S. L. Chen, and S. M. Chuang. 1992. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the gene encoding an extracellular deoxyribonuclease (DNase) from Aeromonas hydrophila. Gene 122175-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, I., P. J. Christie, and D. Dubnau. 2005. The ins and outs of DNA transfer in bacteria. Science 3101456-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, I., and D. Dubnau. 2004. DNA uptake during bacterial transformation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2241-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Boer, P., J. A. Wagenaar, R. P. Achterberg, J. P. M. van Putten, L. M. Schouls, and B. Duim. 2002. Generation of Campylobacter jejuni genetic diversity in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 44351-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, D. R. A. Wareing, R. Ure, A. J. Fox, F. E. Bolton, H. J. Bootsma, R. J. L. Willems, R. Urwin, and M. C. J. Maiden. 2001. Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 3914-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorrell, N., J. A. Mangan, K. G. Laing, J. Hinds, D. Linton, H. Al-Ghusein, B. G. Barrell, J. Parkhill, N. G. Stoker, A. V. Karlyshev, P. D. Butcher, and B. W. Wren. 2001. Whole genome comparison of Campylobacter jejuni human isolates using a low-cost microarray reveals extensive genetic diversity. Genome Res. 111706-1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubnau, D. 1999. DNA uptake in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53217-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutta, C., and A. Pan. 2002. Horizontal gene transfer and bacterial diversity. J. Biosci. 2727-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Endtz, H. P., C. W. Ang, N. van Den Braak, B. Duim, A. Rigter, L. J. Price, D. L. Woodward, F. G. Rodgers, W. M. Johnson, J. A. Wagenaar, B. C. Jacobs, H. A. Verbrugh, and A. van Belkum. 2000. Molecular characterization of Campylobacter jejuni from patients with Guillain-Barré and Miller Fisher syndromes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 382297-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Focareta, T., and P. A. Manning. 1991. Distinguishing between the extracellular DNases of Vibrio cholerae and development of a transformation system. Mol. Microbiol. 52547-2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fouts, D. E., E. F. Mongodin, R. E. Mandrell, W. G. Miller, D. A. Rasko, J. Ravel, L. M. Brinkac, R. T. DeBoy, C. T. Parker, S. C. Daugherty, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, R. Madupu, S. A. Sullivan, J. U. Shetty, M. A. Ayodeji, A. Shvartsbeyn, M. C. Schatz, J. H. Badger, C. M. Fraser, and K. E. Nelson. 2005. Major structural differences and novel potential virulence mechanisms from the genomes of multiple campylobacter species. PLoS Biol. 3e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fry, B. N., S. Feng, Y. Y. Chen, D. G. Newell, P. J. Coloe, and V. Korolik. 2000. The galE gene of Campylobacter jejuni is involved in lipopolysaccharide synthesis and virulence. Infect. Immun. 682594-2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaynor, E. C., S. Cawthraw, G. Manning, J. K. MacKichan, S. Falkow, and D. G. Newell. 2004. The genome-sequenced variant of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC 11168 and the original clonal clinical isolate differ markedly in colonization, gene expression, and virulence-associated phenotypes. J. Bacteriol. 186503-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerry, P., P. M. Pope, D. H. Burr, J. Leifer, S. W. Joseph, and A. L. Bourgeois. 1994. Development and characterization of recA mutants of Campylobacter jejuni for inclusion in attenuated vaccines. Infect. Immun. 62426-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hänninen, M. L. 1989. Rapid method for the detection of DNase of Campylobacters. J. Clin. Microbiol. 272118-2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrington, C. S., F. M. Thomson-Carter, and P. E. Carter. 1999. Molecular epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of Campylobacter jejuni identifies a dominant clonal line within Scottish serotype HS55 populations. Epidemiol. Infect. 122367-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hébert, G. A., D. G. Hollis, R. E. Weaver, M. A. Lambert, M. J. Blaser, and C. W. Moss. 1982. 30 years of campylobacters: biochemical characteristics and a biotyping proposal for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 151065-1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jekel, M., and W. Wackernagel. 1995. The periplasmic endonuclease I of Escherichia coli has amino-acid sequence homology to the extracellular DNases of Vibrio cholerae and Aeromonas hydrophila. Gene 15455-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeon, B., and Q. Zhang. 2007. Cj0011c, a periplasmic single- and double-stranded DNA-binding protein, contributes to natural transformation in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 1897399-7407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jett, B. D., K. L. Hatter, M. M. Huycke, and M. S. Gilmore. 1997. Simplified agar plate method for quantifying viable bacteria. BioTechniques 23648-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kakuda, T., and V. J. DiRita. 2006. Cj1496c encodes a Campylobacter jejuni glycoprotein that influences invasion of human epithelial cells and colonization of the chick gastrointestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 744715-4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen, J. C., C. Szymanski, and P. Guerry. 2004. N-linked protein glycosylation is required for full competence in Campylobacter jejuni 81-176. J. Bacteriol. 1866508-6514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lior, H. 1984. New, extended biotyping scheme for Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli, and “Campylobacter laridis.” J. Clin. Microbiol. 20636-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorenz, M. G., and W. Wackernagel. 1994. Bacterial gene transfer by natural genetic transformation in the environment. Microbiol. Rev. 58563-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manning, G., B. Duim, T. Wassenaar, J. A. Wagenaar, A. Ridley, and D. G. Newell. 2001. Evidence for a genetically stable strain of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 671185-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, W. G., A. H. Bates, S. T. Horn, M. T. Brandl, M. R. Wachtel, and R. E. Mandrell. 2000. Detection on surfaces and in Caco-2 cells of Campylobacter jejuni cells transformed with new gfp, yfp, and cfp marker plasmids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 665426-5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Misawa, N., B. M. Allos, and M. J. Blaser. 1998. Differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni serotype O19 strains from non-O19 strains by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 363567-3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan, G. J., G. F. Hatfull, S. Casjens, and R. W. Hendrix. 2002. Bacteriophage Mu genome sequence: analysis and comparison with Mu-like prophages in Haemophilus, Neisseria and Deinococcus. J. Mol. Biol. 317337-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moulard, M., G. Condemine, and J. Robert-Baudouy. 1993. Characterization of the nucM gene coding for a nuclease of the phytopathogenic bacteria Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol. Microbiol. 8685-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nachamkin, I., J. Engberg, M. Gutacker, R. J. Meinersman, C. Y. Li, P. Arzate, E. Teeple, V. Fussing, T. W. Ho, A. K. Asbury, J. W. Griffin, G. M. McKhann, and J. C. Piffaretti. 2001. Molecular population genetic analysis of Campylobacter jejuni HS:19 associated with Guillain-Barre syndrome and gastroenteritis. J. Infect. Dis. 184221-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker, C. T., B. Quinones, W. G. Miller, S. T. Horn, and R. E. Mandrell. 2006. Comparative genomic analysis of Campylobacter jejuni strains reveals diversity due to genomic elements similar to those present in C. jejuni strain RM1221. J. Clin. Microbiol. 444125-4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearson, B. M., C. Pin, J. Wright, K. I'Anson, T. Humphrey, and J. M. Wells. 2003. Comparative genome analysis of Campylobacter jejuni using whole genome DNA microarrays. FEBS Lett. 554224-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pin, C., M. Reuter, B. Pearson, L. Friis, K. Overweg, J. Baranyi, and J. Wells. 2006. Comparison of different approaches for comparative genetic analysis using microarray hybridization. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 72852-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roop, R. M., II, R. M. Smibert, and N. R. Krieg. 1984. Improved biotyping schemes for Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 20990-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt-Ott, R., S. Pohl, S. Burghard, M. Weig, and U. Gross. 2005. Identification and characterization of a major subgroup of conjugative Campylobacter jejuni plasmids. J. Infect. 5012-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solioz, M., and D. Bienz. 1990. Bacterial genetics by electric shock. Trends Biochem. Sci. 15175-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suerbaum, S., M. Lohrengel, A. Sonnevend, F. Ruberg, and M. Kist. 2001. Allelic diversity and recombination in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 1832553-2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taboada, E. N., R. R. Acedillo, C. D. Carrillo, W. A. Findlay, D. T. Medeiros, O. L. Mykytczuk, M. J. Roberts, C. A. Valencia, J. M. Farber, and J. H. E. Nash. 2004. Large-scale comparative genomics meta-analysis of Campylobacter jejuni isolates reveals low level of genome plasticity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 424566-4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takata, T., T. Ando, D. A. Israel, T. M. Wassenaar, and M. J. Blaser. 2005. Role of dprA in transformation of Campylobacter jejuni. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 252161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor, D. E. 1992. Genetics of Campylobacter and Helicobacter. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 4635-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas, C. M., and K. M. Nielsen. 2005. Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3711-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, Y., and D. E. Taylor. 1990. Natural transformation in Campylobacter species. J. Bacteriol. 172949-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wareing, D. R. A., F. J. Bolton, A. J. Fox, P. A. Wright, and D. L. A. Greenway. 2002. Phenotypic diversity of Campylobacter isolates from sporadic cases of human enteritis in the UK. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92502-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wassenaar, T. M., B. N. Fry, A. J. Lastovica, J. A. Wagenaar, P. J. Coloe, and B. Duim. 2000. Genetic characterization of Campylobacter jejuni O:41 isolates in relation with Guillain-Barre syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38874-876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wassenaar, T. M., B. N. Fry, and B. A. M. van der Zeijst. 1993. Genetic manipulation of Campylobacter: evaluation of natural transformation and electro-transformation. Gene 132131-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wassenaar, T. M., and D. G. Newell. 2000. Genotyping of Campylobacter spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 661-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiesner, R. S., D. R. Hendrixson, and V. J. DiRita. 2003. Natural transformation of Campylobacter jejuni requires components of a type II secretion system. J. Bacteriol. 1855408-5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wösten, M. M. S. M., C. T. Parker, A. van Mourik, M. R. Guilhabert, L. van Dijk, and J. P. M. van Putten. 2006. The Campylobacter jejuni PhosS/PhosR operon represents a non-classical phosphate-sensitive two-component system. Mol. Microbiol. 62278-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu, S. I., S. K. Lo, C. P. Shao, H. W. Tsai, and L. I. Hor. 2001. Cloning and characterization of a periplasmic nuclease of Vibrio vulnificus and its role in preventing uptake of foreign DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 6782-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.