Abstract

Microcin C (McC), an inhibitor of the growth of enteric bacteria, consists of a heptapeptide with a modified AMP residue attached to the backbone of the C-terminal aspartate through an N-acyl phosphamidate bond. Here we identify maturation intermediates produced by cells lacking individual mcc McC biosynthesis genes. We show that the products of the mccD and mccE genes are required for attachment of a 3-aminopropyl group to the phosphate of McC and that this group increases the potency of inhibition of the McC target, aspartyl-tRNA synthetase.

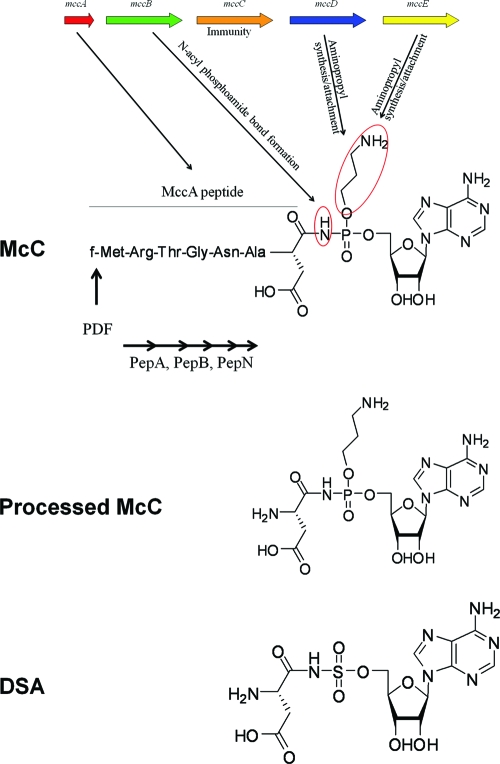

Microcins are a class of small (<10-kDa) antibacterial agents produced by Escherichia coli and its close relatives (1, 2, 15). Microcins are produced from ribosomally synthesized peptide precursors. Some microcins, such as microcin C (McC) studied here, are posttranslationally modified by dedicated maturation enzymes encoded by genes in microcin biosynthetic clusters (15). McC is a heptapeptide with covalently attached C-terminal modified AMP (11). The peptide moiety of McC is encoded by the 21-bp mccA gene, the shortest bacterial gene known (6). McC (Fig. 1) has a molecular mass of 1,178 Da and contains a formylated N-terminal methionine, a C-terminal aspartate instead of the asparagine encoded by the mccA gene, and an AMP residue attached to the α carboxamido group of the modified aspartate through an N-acyl phosphoramidate bond. The phosphoramidate group is additionally esterified by a 3-aminopropyl moiety.

FIG. 1.

Structure of McC. At the top is a schematic diagram showing the McC biosynthesis operon along with the functions of individual mcc gene products based on previously published information and data obtained in this work. Below this the chemical structures of intact McC, processed McC, and the synthetic AspRS inhibitor DSA are shown. The N-acyl phosphamidate bond and the aminopropyl group of McC are circled. Peptidases involved in McC processing are indicated below the McC peptide sequence.

McC is taken up by E. coli through the action of the YejABEF transporter (11) and is processed once it is inside the cell. Processing involves deformylation of the N-terminal Met residue by protein deformylase, followed by degradation by any one of the three broad-specificity aminopeptidases (peptidases A, B, and N) (9). Processed McC (Fig. 1) strongly inhibits translation by preventing the synthesis of aminoacylated tRNAAsp by aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (AspRS) (10). The tRNA aminoacylation reaction catalyzed by aminoacyl tRNA synthetases includes two steps. First, the enzyme activates a cognate amino acid by coupling it to ATP and forming aminoacyl-AMP (aminoacyl-adenylate). The aminoacyl moiety is then transferred to tRNA. Processed McC is structurally similar to aspartyl-AMP but is not hydrolyzable. Thus, the inhibition of AspRS results from tight binding of processed McC in place of aspartyl-adenylate. Whereas intact McC has no effect on the aminoacylation reaction, processed McC has no antibacterial activity at concentrations at which intact McC efficiently inhibits growth (10). Thus, McC is a Trojan horse inhibitor (13): the peptide moiety is required for McC delivery into sensitive cells, where it is processed with subsequent release of the inhibitory payload.

To better understand the process of McC maturation, we prepared derivatives of McC production plasmid pUHAB (5) containing stop codons in the beginning of each of the putative McC biosynthesis genes, mccB, mccD, and mccE; a plasmid lacking both the mccD and mccE genes was also created. We expected that cells harboring these plasmids would produce various intermediates in the McC maturation pathway. No mutation in mccC, a gene coding for an McC export pump, was made, since MccC is involved in immunity rather than McC production (5) and analysis of such a mutation would have been uninformative for the purposes of our study. Plasmids carrying wild-type or mutant mcc clusters were introduced into E. coli K-12 strain BW28357 (9), and the ability of cells harboring these plasmids to inhibit the growth of an McC-sensitive E. coli B test strain (5) was monitored. The results showed that in addition to cells carrying the wild-type plasmid, cells harboring a plasmid lacking the mccD gene were able to inhibit the growth of sensitive cells. Surprisingly, while cells harboring a plasmid with a mutation in mccE did not cause growth inhibition of the test strain, cells harboring a plasmid lacking both mccD and mccE produced clear growth inhibition zones on lawns of sensitive cells.

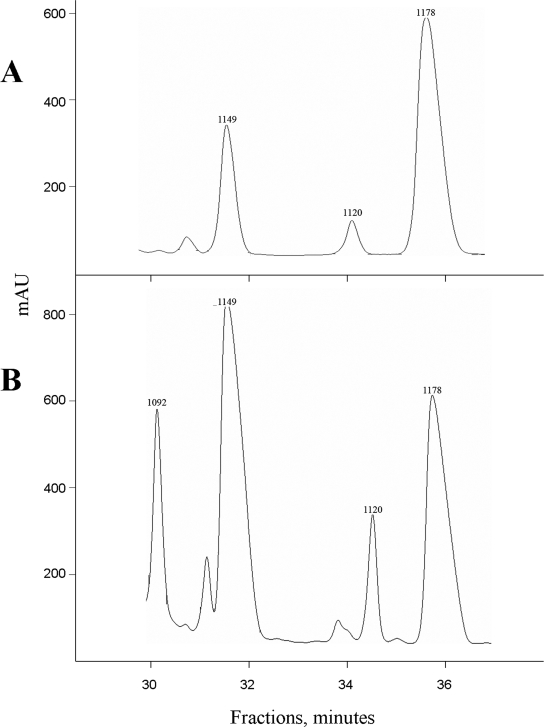

To characterize compounds produced by cells harboring pUHAB and its derivatives, culture medium of producing cells was subjected to the standard McC purification procedure, whose final stage is reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (8, 10). All purified compounds with strong adsorption at 260 nm were characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. The results demonstrated that McC produced by E. coli containing wild-type pUHAB eluted as three distinct peaks on an HPLC chromatogram (Fig. 2A). The major peak contained mature McC (1,178 kDa); material in minor peaks contained mass ions with molecular masses of 1,149 and 1,120 Da. The relative amounts of these three peaks, as measured by absorbance at 260 nm, were 14, 5, and 1, respectively (Table 1). The molecular masses of the compounds from the two minor peaks are consistent with the molecular masses of deformylated McC (1,149 Da) and a formylated species lacking the aminopropyl group (1,120 Da). Both of these hypotheses were confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Tables 2 and 3). A set of two-dimensional NMR spectra, including spectra for 1H,1H correlated spectroscopy (COSY), total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY), rotating frame nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY), and 1H,31P heteronuclear multiple-quantum coherence (HMQC), were recorded for material from minor peaks to assign the 1H NMR spectra and thus to confirm the structures. For the 1,149-Da peak material, all signals were assigned to the structure of McC (7) but without the N-formyl at the terminal methionine residue. The absence of this group led to significant chemical shifts of protons at methionine α- and β-carbons compared to the corresponding protons of intact McC containing formyl-methionine (Table 2). Analysis of the 1,120-Da peak material revealed all structural units characteristic of McC except the n-aminopropanol group. The absence of this group led to a significant shift of the signals of ribose H-5,5′, adenine H-2 and H-8, and aspartate Hβ compared with signals of corresponding protons in the 1H NMR spectra of McC (7). In addition, the chemical shift of 31P in this material (−5.0 ppm) was more upfield than that of McC (−1.6 ppm) (Table 3).

FIG. 2.

HPLC purification of McC and its derivatives and maturation intermediates: HPLC traces for the final step of McC purification from wild-type E. coli cells (A) and mutant cells lacking peptidases A, B, and N (B). The numbers above the peaks indicate molecular weights of microcin and microcin-like compounds determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. mAU, milliabsorbance units.

TABLE 1.

Relative abundance of McC and its derivatives produced by wild-type and pepA pepB pepN mutant cells harboring the wild-type McC production plasmid (mcc+) or plasmids with lesions in mcc genesa

| Mol wt of molecule | Relative abundance (%) in:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type cells with mcc+ plasmid | pepA pepB pepN cells with mcc+ plasmid | Wild-type cells with mccB mutant plasmid | pepA pepB pepN cells with mccB mutant plasmid | Wild-type cells with mccD mutant plasmid | pepA pepB pepN cells with mccD mutant plasmid | Wild-type cells with mccE mutant plasmid | pepA pepB pepN cells with mccE mutant plasmid | Wild-type cells with mccDE mutant plasmid | pepA pepB pepN cells with mccDE mutant plasmid | |

| 1,178 | 70 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1,149 | 23 | 63 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1,120 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 12 | 0 | 33 | 100 | 19 |

| 1,092 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 88 | 0 | 67 | 0 | 81 |

TSP (2,2,3,3-tetradeutero-3-trimethylsilylpropionic acid) was used as an internal standard with values given in parts per million.

TABLE 2.

NMR data for the McC derivative with a molecular weight of 1,149 at 30°C and pD 3 in D2O

| Residue | 1H NMR chemical shifts (δH TSP 0.0)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | β | γ | δ/ɛ | CHO | |

| Met | 4.15 (4.53) | 2.17 (2.08-2.01) | 2.58 (2.50-2.55) | 2.09 (2.09) | (8.13) |

| Arg | 4.47 (4.46) | 1.86; 1.77 (1.88-1.79) | 1.67 (1.64) | 3.19 (3.19) | |

| Thr | 4.38 (4.39) | 4.23 (4.25) | 1.20 (1.21) | ||

| Gly | 3.97 (3.98) | ||||

| Asn | 4.68 (4.69) | 2.78; 2.70 (2.80-2.72) | |||

| Ala | 4.28 (4.30) | 1.34 (1.35) | |||

| Asp | 4.57 (4.56) | 2.88; 2.78 (2.76-2.68) | |||

| Aliphatic | 4.23 (4.18) | 2.04 (2.03) | 3.10 (3.09)b | ||

| H-1′ | H-2′ | H-3′ | H-4′ | H-5′ | |

| Ribose | 6.16 (6.13) | 4.73 (4.76) | 4.48 (4.49) | 4.41 (4.41) | 4.45; 4.41 (4.41-4.43)b |

| H-2 | H-8 | ||||

| Adenine | 8.41 (8.29) | 8.45 (8.37) | |||

The corresponding chemical shifts of intact McC at 27°C and pD 4.3 (7) are indicated in parentheses.

31P at δP for 1,149-Da McC derivative, −0.50 (31P at δP for intact McC, −1.63).

TABLE 3.

NMR data for the McC derivative with a molecular weight of 1,120 at 30°C and pD 3 in D2O

| Residue | 1H NMR chemical shifts (δH TSP 0.0)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | β | γ | δ/ɛ | Others | |

| f-Met | 4.54 | 2.08; 2.02 | 2.56 | 2.10 | 8.14 (CHO) |

| Arg | 4.47 | 1.89; 1.78 | 1.63 | 3.16 | |

| Thr | 4.39 | 4.25 | 1.21 | ||

| Gly | 4.03; 3.95 | ||||

| Asn | 4.73 | 2.84; 2.74 | |||

| Ala | 4.32 | 1.38 | |||

| Asp | 4.55 | 2.71; 2.61 | |||

| H-1 | H-2 | H-3 | H-4 | H-5,5′ | |

| Ribose | 6.14 | 4.76 | 4.43 | 4.37 | 4.12, 4.12b |

| H-2 | H-8 | ||||

| Adenine | 8.27 | 8.52 | |||

The one-dimensional 1H and 31P NMR spectra, as well as the two-dimensional 1H,1H COSY, TOCSY, ROESY, and 1H,31P HMQC spectra were recorded with a DRX-500 Bruker spectrometer for a solution of the material (∼1 mg) in 0.2 ml of 99.96% D2O at 30°C with TSP (δH 0.0) as the internal standard and 80% H3PO4 as the external standard for 31P NMR. The two-dimensional experiments were performed using standard pulse sequences from the Bruker software. A mixing time of 200 ms was used in the TOCSY experiment. A spin lock time of 300 ms was used in the ROESY experiment. The 1H,31P HMQC experiment was optimized for the coupling constant 8 Hz.

Phosphorus signal at δP, −5.0.

No McC-like material could be purified from cells harboring pUHAB derivatives lacking a functional mccB gene (Table 1). This result is expected, as recent in vitro work performed by the Walsh group demonstrated that the product of this gene is responsible for the addition of the AMP moiety to the MccA peptide (14).

Cells harboring the pUHAB plasmid lacking a functional mccD gene produced only the 1,120-Da compound (Table 1). This result is consistent with the idea that the product of mccD is involved in the addition of the 3-aminopropyl group to the phosphate of the nucleopeptide synthesized by MccB.

No McC-like material could be purified from cells harboring pUHAB derivatives lacking a functional mccE gene (Table 1). However, culture medium of cells carrying the pUHAB derivative lacking both mccD and mccE produced a single 1,120-Da peak (Table 1).

pUHAB and its derivatives were also introduced into cells of E. coli strain BW28357, a triple mutant lacking aminopeptidases PepA, PepB, and PepN. Previously, we showed that such cells are unable to process McC and, as a consequence, are fully resistant to it (9). We reasoned that using such cells for production of McC and its derivatives might reveal McC maturation intermediates that are either toxic to or rapidly processed in the wild-type cells. Overall, the results of antibacterial activity tests performed with triple-mutant cells harboring various mcc plasmids matched the results obtained with wild-type cells, with one surprising exception: clear growth inhibition zones were observed around cells harboring a plasmid with a disrupted mccE gene (no haloes were observed around wild-type cells harboring the same plasmid). HPLC and mass spectrometric analysis of McC produced by triple-mutant cells harboring the wild-type pUHAB plasmid revealed 1,178- and 1,149-Da peaks, but, in contrast to the situation observed with wild-type producing cells, the latter compound was the major compound (Table 1 and Fig. 2B) (the ratio of the 1,178- and 1149-Da compounds as determined by the absorbance at 260 nm of the corresponding HPLC peaks was ca. 1:2), indicating that deformylation of the MccA peptide or mature McC is activated in these cells, as suggested previously (9). In addition to the 1,120-Da peak, a new peak of 1,092 Da was also present. The 1,092-Da compound corresponds to deformylated McC lacking the aminopropyl group. Cells lacking the three peptidases and harboring the pUHAB derivative with a disrupted mccD gene produced two compounds, a minor compound (1,120 Da) corresponding to formylated McC lacking the aminopropyl group and a major compound with a molecular mass of 1,092 Da. These compounds were produced at about a 1:7 ratio (Table 1). The same compounds were also produced by mutant cells harboring a double-mutant plasmid with disrupted mccD and mccE genes (Table 1). Material produced by mutant cells harboring pUHAB with a disrupted mccE gene also contained the 1,092- and 1,120-Da compounds (Table 1). Thus, no McC derivative containing the aminopropyl group is detected in the absence of either MccD or MccE. Possibly, one of these proteins is required for production of the aminopropyl group, while the other is responsible for attachment of this group to a nucleopeptide synthesized by MccB. MccD is the likely candidate for the latter role, since sequence analysis indicates that it is similar to protein methyltransferases (15).

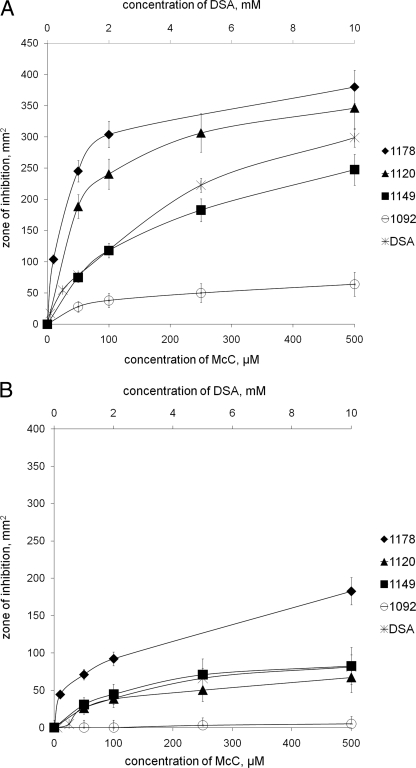

The results of antibacterial assays described above do not allow comparisons of the antibacterial activities of McC and its derivatives because in most cases (i) mixtures of various compounds are produced and (ii) the amounts of compounds produced vary. We tested the ability of purified mature McC, McC derivatives lacking the formyl or aminopropyl group, or McC lacking both groups to inhibit E. coli growth. The results are shown in Fig. 3. As Fig. 3A shows, removal of the aminopropyl group had little effect on antibacterial activity against E. coli B tester cells, while deformylation significantly decreased the activity. Removal of both groups strongly decreased the activity. McC and its derivatives were also tested with E. coli K-12 strain BW28357, which is less sensitive to wild-type McC than E. coli B cells are. In this case, deformylation of wild-type McC or removal of the aminopropyl group decreased activity to about the same extent (Fig. 3B). Removal of both groups virtually abolished activity. Thus, in the presence of N-terminal formyl, the aminopropyl group makes a much larger contribution to antibacterial action of McC against a K-12 strain than against a B strain. The exact reasons for such strong strain-specific effects of aminopropyl on McC activity may be quite complex, since the overall efficiency of McC antibacterial action should be a function of (at least) the uptake, processing, and stability of processed McC in the target cell cytoplasm. The sensitivity of the processed McC target, AspRS, should not directly contribute to differential sensitivity of B and K-12 cells to McC, since the deduced primary sequences of enzymes from the two strains are identical (unpublished observations). E. coli K-12 cells are much less sensitive than B cells to aspartyl-sulfamoyl-adenosine (DSA) (Fig. 3), a synthetic AspRS inhibitor (3) that mimics aspartyl adenylate but contains a nonhydrolyzable sulfamoyl group instead of the N-acyl phosporamidate found in McC (Fig. 1). Since DSA does not need to be processed to inhibit AspRS, the differences in the susceptibilities of K-12 and B strains must be due to factors other than processing.

FIG. 3.

Antibacterial activity of McC and its derivatives: sizes of growth inhibition zones observed around 5-μl drops of solutions containing different concentrations of McC, its derivatives, or DSA on E. coli B (A) and K-12 (B) lawns. The concentrations of McC and its derivatives are indicated on the x axis at the bottom. The concentrations of DSA are indicated on the x axis at the top. For each compound, three independent experiments were performed. Standard deviations for growth inhibition zones for each compound are indicated by error bars.

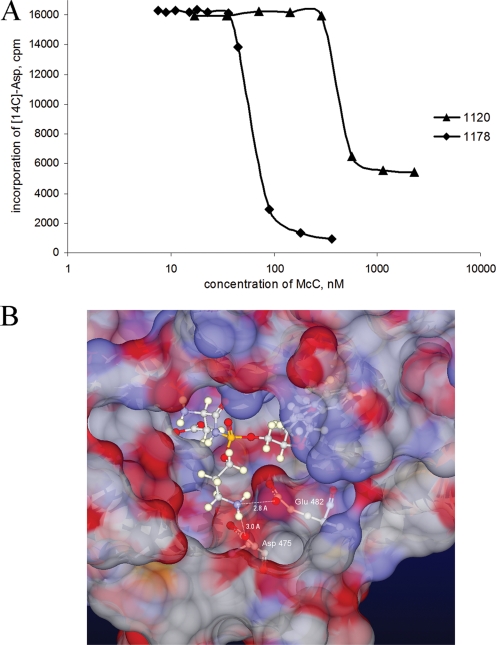

We determined the contribution of the aminopropyl group to the ability of processed McC to inhibit AspRS in cell extracts. Since processing of corresponding formylated and deformylated McC variants results in identical processed compounds, only intact McC and formylated McC lacking the aminopropyl group were used. Equal amounts of McC and its derivative were incubated with B or K-12 cell extracts long enough to allow complete processing (the time required for processing was determined before the experiment [see Fig. 5; data not shown]), and aminoacylation reactions with radioactively labeled aspartate were performed. In the course of these experiments, we observed that in K-12 cell extracts, initial incubation with McC or its derivatives led to inhibition of the aminoacylation reactions; however, eventually aminoacylation was restored to almost the initial (without McC) levels (data not shown). This unusual behavior is due to gradual inactivation of processed McC in K-12 extracts. This inactivation involves covalent modification of processed McC by Rim acetylases (our unpublished observations) and will be reported in detail elsewhere (M. Novikova et al., unpublished data). The presence of significant amounts of activity that inactivates processed McC in K-12 extracts doubtlessly contributes to the higher level of McC resistance of these cells. This activity also makes it difficult to interpret in vitro results obtained with K-12 extracts; the remainder of this paper deals with B cell extracts, in which the rate of processed McC inactivation activity is low (unpublished observations).

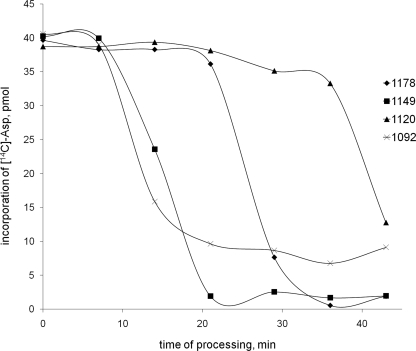

FIG. 5.

Processing of McC and its derivatives in E. coli B cytoplasmic extracts. E. coli S30 extracts were combined with McC or McC derivatives. At various times, aliquots of reaction mixtures were withdrawn and the tRNAAsp aminoacylation reaction was carried out. The amounts of aminoacylated tRNAAsp (measured by determining the incorporation of [C14]Asp into trichloroacetic acid-precipitable material) are shown. See reference 10 for experimental details. The curves are representative of curves obtained in three independent experiments.

In B cell extracts, half-inhibition of AspRS activity occurred in the presence of ∼50 nM of McC. With the compound lacking aminopropyl, half-inhibition was obtained at a ∼10-fold-higher concentration; the same concentration of DSA was required for half-inhibition of the aminoacylation reaction (data not shown). These results suggest that the presence of an aminopropyl group increases the affinity of processed McC for AspRS. In addition, the fact that the level of AspRS inhibition with saturating concentrations of an McC derivative lacking aminopropyl was lower than that with wild-type McC is consistent with an idea that the aminopropyl group alters the interaction of processed McC with its target. A possible explanation for these observations is provided by the results of molecular modeling shown in Fig. 4B. We have docked the processed McC molecule in the aspartyl-adenylate-binding site of E. coli AspRS using in-house software for molecular docking based on local binding site similarity (12). In the modeled structure, the conformation of the core of the processed McC molecule resembles that of the native aspartyl-adenylate ligand cocrystallized with the protein (4). The positively charged nitrogen atom of the propylamine group is close to negatively charged side chain oxygen atoms of Asp475 and Glu482, two residues that are strictly conserved in AspRSs of gammaproteobacteria (data not shown). Favorable interactions between the amine of the propylamine group and a negatively charged pocket in the vicinity of catalytic AspRS could increase the on rate of processed McC binding to AspRS. The additional interaction may also change the structure of the enzyme-inhibitor complex by, for example, “locking” the enzyme in a closed conformation and thus decreasing the rate of dissociation of the inhibitor from the complex. Together, these effects may explain the increased apparent inhibition constant and the lower residual levels of AspRS activity at a saturating concentration of processed McC compared to the results for a derivative lacking the aminopropyl group.

FIG. 4.

The aminopropyl group increases the efficiency of AspRS inhibition by processed McC. (A) E. coli S30 extracts were incubated in the presence of different concentrations of McC or the McC derivative lacking the aminopropyl group for a time period sufficient for complete processing. Next, the tRNAAsp aminoacylation reaction was carried out. The amounts of aminoacylated tRNAAsp (measured by determining the incorporation of [C14]Asp in trichloroacetic acid-precipitable material) are shown. See reference 10 for experimental details. The curves are representative of curves obtained in three independent experiments. (B) Structural modeling of the interaction of processed McC with E. coli AspRS: surface representation of E. coli AspRS (PDB code 1c0a) (4) residues within 10 Å of bound aspartyl-AMP and modeled processed McC (both shown using ball-and-stick representation). Distances between the modeled position of the propylamine nitrogen atom and side chain oxygen atoms of Glu482 and Asp475 are indicated.

To determine the effect of McC modifications on processing in vitro, equal amounts of McC and its three derivatives were combined with E. coli B extracts and incubated for various amounts of time, and reaction aliquots were assayed for tRNAAsp aminoacylation (note that the aminoacylation reaction is much faster than the processing reaction). The results (Fig. 5) show that in the absence of the formyl group processing occurs faster, while the presence or the absence of aminopropyl does not affect the processing rate of deformylated McC. However, the absence of aminopropyl significantly slows processing in the presence of the formyl group. These results may indicate that protein deformylase, the enzyme that initiates processing of formylated McC and its derivatives, is stimulated by the presence of the aminopropyl group. Additional experiments are needed to prove this hypothesis.

The impetus of this study came from the work of Fomenko et al. (5), who showed that cells harboring McC-producing plasmids with genetic lesions in mccD and/or mccE produced altered microcin-like compounds, which were named McC* but whose nature was not established. Our results show that the McC* detected in the study of these workers must have been a mixture of formylated and deformylated McC lacking the aminopropyl group. Since the work of Roush et al. (14) established that in vitro MccB can use ATP for modification of the MccA peptide, one has to assume that MccD/MccE-catalyzed addition of aminopropyl to the McC precursor occurs after the MccB-catalyzed coupling of the peptide and nucleotide has occurred. The absence of the aminopropyl group reduces, but does not prevent, E. coli AspRS inhibition. Aminopropyl most likely increases the potency of processed McC through favorable interactions between the amino group and a negatively charged pocket formed adjacent to the AspRS catalytic center. Although residues forming the negatively charged pocket with which aminopropyl likely interacts are strictly conserved, homologs of mccD and mccE are absent from several bioinformatically predicted operons for McC homolog biosynthesis (15). One can therefore hypothesize that the mccD and mccE genes are a later addition to the basic mccA-mccB-mccC cluster, which alone is sufficient for production of a simplified peptide nucleotide antibiotic and immunity of the producing cell to it.

The reasons why no McC derivatives are produced by wild-type cells lacking mccE are unclear. The fact that cells lacking peptidases A, B, and N produce McC in the absence of mccE seems to suggest that intracellular processing of McC is responsible for the lack of production by wild-type cells. However, while processing of McC should have been toxic to the producing cell, wild-type E. coli harboring the McC-producing plasmid without the mccE gene grew normally, indicating that the involvement of cellular peptidases in McC production in the absence of mccE may be indirect. The matter is further complicated by the finding that the wild-type cells produce McC when both mccE and mccD are deleted. Experiments aimed at biochemical characterization of recombinant MccD and MccE and their role in McC maturation using the recently developed in vitro maturation system (14) should shed light on this problem.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIAID North Eastern Biodefense Center grant U54 AI057158, by a Burroughs Wellcome Career Award, by a grant from the Russian Academy of Sciences Presidium program in Molecular and Cellular Biology, by a Rutgers University Technology Commercialization Fund grant (to K.S.), and by Russian Foundation for Basic Research grant 06-04-48865 (to A.M.). G.H.V. is a holder of an IWT scholarship from Flanders, Belgium.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 January 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baquero, F., and F. Moreno. 1984. The microcins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 23117-124. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baquero, F., D. Bouanchaud, M. C. Martinez-Perez, and C. Fernandez. 1978. Microcin plasmids: a group of extrachromosomal elements coding for low-molecular-weight antibiotics in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 135342-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernier, S., P. M. Akochy, J. Lapointe, and R. Chenevert. 2005. Synthesis and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitory activity of aspartyl adenylate analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1369-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eiler, S., A. Dock-Bregeon, L. Moulinier, J. C. Thierry, and D. Moras. 1999. Synthesis of aspartyl-tRNA(Asp) in Escherichia coli—a snapshot of the second step. EMBO J. 186532-6541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fomenko, D. E., A. Z. Metlitskaya, J. Peduzzi, C. Goulard, G. Katrukha, L. V. Gening, S. Rebuffat, and I. A. Khmel. 2003. Microcin C51 plasmid genes: possible source of horizontal gene transfer. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 472868-2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez-Pastor, J. E., J. L. San Millan, and F. Moreno. 1994. The smallest known gene. Nature 369281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guijarro, J. I., J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, F. Baleux, J. L. San Millan, M. A. Castilla, M. Rico, F. Moreno, and M. Delepierre. 1995. Chemical structure and translation inhibition studies of the antibiotic microcin C7. J. Biol. Chem. 27023520-23532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazakov, T., A. Metlitskaya, and K. Severinov. 2007. Amino acid residues required for maturation, cell uptake, and processing of translation inhibitor microcin C. J. Bacteriol. 1892114-2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazakov, T., G. H. Vondenhoff, M. K. A. Datsenko, Novikova, M., A. Metlitskaya, B. L. Wanner, and K. Severinov. 2008. Escherichia coli peptidase A, B, or N can process translation inhibitor microcin C. J. Bacteriol. 1902607-2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metlitskaya, A., T. Kazakov, A. Kommer, O. Pavlova, I. Krashenninikov, V. Kolb, I. Khmel', and K. Severinov. 2006. Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase is the target of peptidenucleotide antibiotic microcin C. J. Biol. Chem. 28118033-18042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novikova, M., A. Metlitskaya, A., K. Datsenko, T. Kazakov, A. Kazakov, B. Wanner, and K. Severinov. 2007. The Escherichia coli Yej ABC transporter is required for the uptake of translation inhibitor microcin C. J. Bacteriol. 1898361-8365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramensky, V., A. Sobol, N. Zaitseva, A. Rubinov, and V. Zosimov. 2007. A novel approach to local similarity of protein binding sites substantially improves computational drug design results. Proteins 69349-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reader, J. S., P. T. Ordoukhanian, J. G. Kim, V. de Crecy-Lagard, I. Hwang, S. Farrand, and P. Schimmel. 2005. Major biocontrol of plant tumors targets tRNA synthetase. Science 3091533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roush, R. F., E. M. Nolan, F. Löhr, and C. T. Walsh. 2008. Maturation of an Escherichia coli ribosomal peptide antibiotic by ATP-consuming N-P bond formation in microcin C7. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1303603-3609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Severinov, K., E. Semenova, A. Kazakov, T. Kazakov, and M. S. Gelfand. 2007. The post-translationally modified microcins. Mol. Microbiol. 61380-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]