Abstract

Lateral gene transfer is a significant contributor to the ongoing evolution of many bacterial pathogens, including β-hemolytic streptococci. Here we provide the first characterization of a novel integrative conjugative element (ICE), ICESde3396, from Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (group G streptococcus [GGS]), a bacterium commonly found in the throat and skin of humans. ICESde3396 is 64 kb in size and encodes 66 putative open reading frames. ICESde3396 shares 38 open reading frames with a putative ICE from Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus [GBS]), ICESa2603. In addition to genes involves in conjugal processes, ICESde3396 also carries genes predicted to be involved in virulence and resistance to various metals. A major feature of ICESde3396 differentiating it from ICESa2603 is the presence of an 18-kb internal recombinogenic region containing four unique gene clusters, which appear to have been acquired from streptococcal and nonstreptococcal bacterial species. The four clusters include two cadmium resistance operons, an arsenic resistance operon, and genes with orthologues in a group A streptococcus (GAS) prophage. Streptococci that naturally harbor ICESde3396 have increased resistance to cadmium and arsenate, indicating the functionality of genes present in the 18-kb recombinogenic region. By marking ICESde3396 with a kanamycin resistance gene, we demonstrate that the ICE is transferable to other GGS isolates as well as GBS and GAS. To investigate the presence of the ICE in clinical streptococcal isolates, we screened 69 isolates (30 GGS, 19 GBS, and 20 GAS isolates) for the presence of three separate regions of ICESde3396. Eleven isolates possessed all three regions, suggesting they harbored ICESde3396-like elements. Another four isolates possessed ICESa2603-like elements. We propose that ICESde3396 is a mobile genetic element that is capable of acquiring DNA from multiple bacterial sources and is a vehicle for dissemination of this DNA through the wider β-hemolytic streptococcal population.

Lateral gene transfer (LGT) plays a profound role in the generation of genetic diversity within bacterial pathogens (28, 35). LGT rapidly facilitates the adaptation of bacteria to novel environments and leads to the expansion of virulence determinants. Conjugative transposons are major mediators of LGT in prokaryotes and together with integrative plasmids are known as integrative conjugative elements (ICEs). ICEs often carry genes for auxiliary traits such as resistance to antibiotics and heavy metals and are widely implicated as the primary disseminator of such phenotypes (9).

The β-hemolytic streptococci constitute a group of human and animal pathogens that cause a wide variety of diseases in their respective hosts (24). The human pathogens include Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus [GAS]), Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus [GBS]), and Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (human group C and group G streptococcus [GGS]). Historically, GAS is associated with diseases such as pharyngitis, impetigo, scarlet fever, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, rheumatic disease, and rheumatic heart disease (16). In the 1980s, GAS emerged as a cause of a serious and potentially fatal invasive disease (15, 47) which is estimated to kill between 1,000 and 1,700 people each year in the United States (6). Similarly, GBS, a major veterinary pathogen, emerged as a leading cause of bacterial invasive disease in newborns in the 1970s (21). GGS has traditionally been considered a commensal organism found as part of the normal flora of the skin, throat, and other mucosal surfaces and caused only opportunistic infections in individuals with underlying risk factors (12). However, GGS is increasingly associated with a spectrum of disease in healthy individuals which overlaps that of GAS. These include epidemic pharyngitis, bacteremia, puerperal sepsis, peritonitis, cellulitis, septicemia, infective endocarditis, and glomerulonephritis (12, 14, 22, 23, 29, 30, 34, 49, 56). Additionally, GGS is also associated with serious streptococcal invasive diseases, including necrotizing fasciitis and toxic shock syndrome (57).

Changes in genome content, arising through mutations (e.g., allelic variation or gene duplication) or LGT have been hypothesized to contribute to changes in the disease association of GAS and GBS in the last few decades (1, 2, 5, 54, 58). Genome sequencing and other genetic studies have also reinforced the importance of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) in generating diversity within these species (5, 26, 37, 48, 51, 52). In fact, the pangenomes (representing the entire genetic repertoire of a species) of both GAS and GBS are considered to be open (51), implying that new genes continue to enter the population though ongoing interspecies LGT. In the absence of genomic sequences, our understanding of genomic variation in GGS is less clear. Given the close genetic relatedness between GAS, GBS, and GGS (24) and evidence that GGS genomes are more “chaotic” than GAS genomes (33), it is likely that the GGS pangenome is also open and is participating in interspecies LGT. In this regard, several studies have provided evidence for LGT involving GGS and GAS (27, 33). Our previous molecular epidemiological study also reported that intra- and interspecies LGT is likely to be occurring in environments where GGS and GAS are endemic (18, 19).

To date there has been little or no direct evidence for ICE mediated cross-species LGT between GGS and GAS or GGS and GBS. In the current study, we have provided the first detailed genetic and functional characterization of an ICE from GGS and demonstrate its conjugative transfer to both GAS and GBS. Significantly, ICESde3396 contains a large internal recombinogenic region that carries functional genes and operons derived from both streptococcal and nonstreptococcal species, implying that it is a vehicle for dissemination of novel genes through the wider β-hemolytic streptococcal population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and molecular methods.

S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis NS3396 was isolated from a patient presenting with pharyngitis and acute rheumatic fever (19). All other GGS, GAS, and GBS isolates (Table 1) were isolated from individuals presenting with streptococcal disease or as part of community surveys within Australia (17, 19, 20). The isolates used in this study are nonclonal, as determined by emm typing for GAS and GGS and serotyping for GBS. All streptococci were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth or on Todd-Hewitt agar supplemented with 2% horse blood. Growth medium was supplemented with kanamycin (500 μg/ml) and/or streptomycin (400 μg/ml) when appropriate.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Isolatea | Emm type/serotype | Site of isolation | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGS | |||

| NS3396 | STG480 | Throat | 19 |

| G120 | STG4831 | Throat | |

| G121 | STC74 | Unknown | 19 |

| G122 | STC74 | Unknown | 19 |

| GGS10 | STG6 | Unknown | 19 |

| GGS24 | STG6 | Unknown | 19 |

| GGS48 | STG4831 | Unknown | 19 |

| MD013 | STG10 | Skin | This study |

| MD048 | STG485 | Skin | 17 |

| MD077 | STG10 | Skin | 17 |

| MD128GCS | STG93464 | Throat | 17 |

| MD172 | STC74a | Skin | 17 |

| MD225 | STC74a | Peritoneum | 17 |

| MD263 | STC6979 | Sputum | This study |

| MD284 | STG11 | Skin | 17 |

| MD323GCS | STG62647 | Blood | 17 |

| MD378 | STG643 | Skin | This study |

| MD409 | STG10 | Skin | This study |

| MD448 | STG10 | Skin | 17 |

| MD543 | STG643 | Skin | 17 |

| MD581 | STC1400 | Skin | This study |

| MD699 | STG62647 | Skin | 17 |

| MD813 | STC74a | Blood | 17 |

| MD864 | STG166b | Skin | 17 |

| MD894GCS | STG62647 | Urine | 17 |

| MD896 | STG11 | Skin | 17 |

| NS1121 | STG4831 | Unknown | 19 |

| NS383 | New type | Blood | 19 |

| NS542 | STG652 | Blood | 19 |

| NS752 | STG6 | Blood | 19 |

| GBS | |||

| RBH01 | III | Vagina | This study |

| RBH02 | Ib | Vagina | This study |

| RBH03 | III | Vagina | This study |

| RBH04 | 1a/V | Vagina | This study |

| RBH05 | V | Vagina | This study |

| RBH06 | II | Vagina | This study |

| RBH07 | Nontypeable | Vagina | This study |

| RBH08 | Ia | Vagina | This study |

| RBH09 | V | Vagina | This study |

| RBH10 | V | Vagina | This study |

| RBH11 | III | Vagina | This study |

| RBH12 | V | Vagina | This study |

| RBH13 | III | Vagina | This study |

| RBH14 | 1b | Vagina | This study |

| RBH15 | Nontypeable | Vagina | This study |

| RBH16 | III | Vagina | This study |

| B36PS | IV | Vagina | This study |

| B37PD | V | Vagina | This study |

| 50VD | 1a | Vagina | This study |

| GAS | |||

| NS282 | st6030.1 | Skin | 20 |

| NS344 | 1 | Blood | 20 |

| NS351 | 58 | Skin | 20 |

| NS414 | 11 | Unknown | 20 |

| NS180 | 74 | Throat | 20 |

| NS195 | 19 | Blood | 20 |

| NS8 | 85 | Blood | 20 |

| NS14 | 102 | Skin | 20 |

| NS179 | 9.1 | Skin | 20 |

| NS20 | 75.1 | Blood | 20 |

| NS199 | 112 | Throat | 20 |

| NS204 | 2 | Blood | 20 |

| NS83 | stNS554 | Blood | 20 |

| NS205 | 56 | Blood | 20 |

| NS210 | 22 | Blood | 20 |

| NS225 | 99 | Blood | 20 |

| NS226 | 4.2 | Blood | 20 |

| NS235 | 24 | Blood | 20 |

| NS236 | 77 | Throat | 20 |

| NS240 | st2904 | Blood | 20 |

GGS isolates possessing the group C carbohydrate are indicated by a superscript GCS.

Genomic DNA extraction, restriction enzyme digestions, ligations, PCR, and DNA sequencing all utilized standard procedures. Adapter PCR analysis was performed as previously described (18, 43). Briefly, genomic DNA was partially digested with a BclI and/or HindIII, purified, and ligated with a 5′ phosphorylated oligonucleotide adaptor containing BclI or HindIII overhangs, respectively. Standard PCR was then undertaken, using one primer complementary to the adapter sequence and another internal primer sequence specific for the DNA sequence of interest. The resulting products were purified after agarose gel electrophoresis and subject to DNA sequence analysis. The nucleotide (nt) sequence of adapter PCR primers is shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primer combinations and expected amplicon sizes of the three ICESde3396 regions targeted in the PCR screening of clinical GGS, GBS, and GAS isolatesa

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′) | Locationa | Expected size (kb)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1F | CTACTTTTTGTTGCCATTTGG | Amplification of the R1 region (orf1 to orf5) in ICESde3396 | 3.1 | This study |

| R1R | GAGTCAGTGTCCAAACTTTTCG | |||

| R2F | GTTTAAATCCCAGATAAGCTACG | Amplification of the R2 region (orf17 to orf23) | 4.2 | This study |

| R2R | ATCGATTATGATTTTGGTCAACG | |||

| R3F | TTCCTACTTGTACCAATACTGC | Amplification of the R3 region (orf55 to orf61) | 3.2 | This study |

| R3R | GAGTGACTTAGTTATGAAGGACG | |||

| Adapter1 | GATCCGCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAAC | Adapter PCR | 18, 43 | |

| Adapter2 | AGCTCGCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAAC |

ORFs from ICESde3396.

Determination of the ICESde3396 nucleotide sequence.

A combination of long PCR (11), primer walking, and adapter PCR was employed to determine the complete sequence of ICESde3396. Primers used for these activities were based on DNA fragments identified by the initial genomic subtraction of NS3396 (19) or on the sequence of the putative GBS conjugative transposon present in the GBS 2603V/R genome (52). Forward and reverse DNA strand contigs were assembled using the Staden package. Assignment of open reading frames (ORFs) was achieved using the bacterial annotation system, BASys (53). The complete ICESde3396 sequence is deposited in the GenBank database under accession number EU142041.

PCR screening of streptococci.

The presence of ICESde3396 and ICESa2603 in GGS, GBS, and GAS was determined by PCR amplification of DNA representing three separate regions of ICESde3396 (Fig. 1). The presence of R1 in streptococcal genomes was determined by amplification of a 3.1-kb fragment spanning from ICESde3396_orf1 to ICESde3396_orf5. The 4.2-kb amplicon used to identify the presence of the R2 region extends from ICESde3396_orf17, within R1, to ICESde3396_orf23 in R2. We chose to amplify a region extending from R1 to R2 to ensure that these regions were adjacent to one another in the streptococcal genomes examined. The R3 region was identified by amplification of a 3.2-kb fragment (ICESde3396_orf55 to ICESde3396_orf61). The nucleotide sequences of primers used for PCR screening of the streptococcal isolates for the presence of R1, R2, and R3 regions are shown in Table 2.

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization and protein alignment of ICESde3396 with ICESa2603. Individual ORFs are represented by block arrows. Conserved proteins exhibiting greater than 45% amino acid identity between ICESde3396 and ICESa2603 are represented by the shading. The ICESde3396 genome was annotated using the bacterial annotation system BASys (53) and comparisons performed using the Artemis Comparison Tool (10). ORFs in the 18.1-kb recombinogenic region are depicted by block arrows. The four gene clusters in the 18-kb recombinogenic region and corresponding regions in other bacterial genomes are indicated by dashed lines. The R1, R2, and R3 regions are also shown.

Conjugation of streptococci.

Filter mating experiments were carried out according to Smith and Guild (46). Prior to the mating, an antibiotically marked ICE was constructed by introducing a kanamycin resistance gene into ICESde3396. This was achieved by amplifying a 760-bp segment of ICESde3396 extending from nt 15061 to nt 15820 with flanking EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites. Another 638-bp segment extending from nt 17305 to nt 17942 in the ICE was also amplified with flanking BamHI and SpeHI restriction sites. The two fragments were ligated through their BamHI sites, and the product was cloned into pSF152. A kanamycin resistance gene was subsequently cloned into the internal BamHI site, creating pSF152-ICE:Km. pSF152-ICE:Km was transformed into NS3396 using standard procedures (41) and recombinants (NS3396 ICESde3396:Km) selected on Todd-Hewitt agar containing 500 μg/ml kanamycin. Integration of the plasmid into the NS3396 genome was confirmed via PCR and Southern hybridization.

For all conjugations, NS3396 ICESde3396:Km was used as the donor strain. Spontaneous streptomycin-resistant GGS, GBS, and GAS isolates were used as recipient strains. Three milliliters of an overnight culture containing recipient organisms was supplemented with MgSO4 (10 mM), bovine serum albumin (2 mg/ml), and DNase I (200 U). The donor culture (300 μl) was then added, and the entire bacterial culture was filtered onto nitrocellulose. After filtering, the membrane was placed cell side up on Todd-Hewitt agar, overlaid with 5 mm of 1.5% Todd-Hewitt agar, and incubated at 37°C overnight. The next day, the filter paper was retrieved, placed into a 50-ml tube containing Todd-Hewitt broth, and vortexed for 10 s. The resulting suspension was serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline and plated onto Todd-Hewitt agar containing kanamycin and streptomycin. The conjugation frequency was determined by dividing the average number of transconjugants by the average number of donors for each experiment.

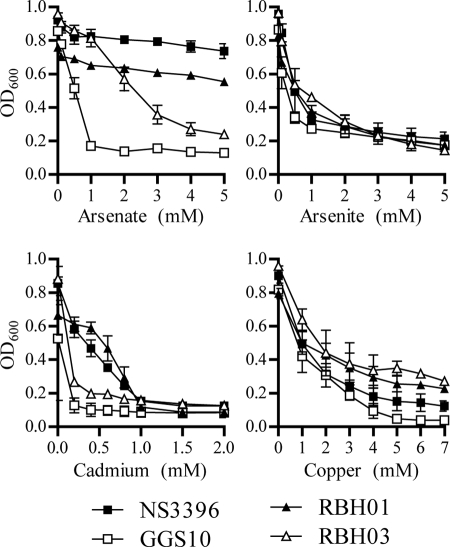

Resistance to cadmium, arsenite, arsenate, and copper.

Overnight cultures of GGS and GBS were resuspended in Todd-Hewitt broth to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. Aliquots of the cultures were supplemented with cadmium chloride (0 to 2 mM), sodium arsenate (0 to 7 mM), sodium arsenite (0 to 5 mM), or copper sulfate (0 to 7 mM) and grown at 37°C. The optical density of cultures was monitored at 600 nm. The OD600 of cultures after 5 h of growth in the presence of arsenate, arsenite, or copper or 24 h of growth in the presence of cadmium are presented.

RESULTS

General features of ICESde3396.

We recently described genomic subtraction studies using pathovar (NS3396) and nonpathovar strains of GGS (19). A large proportion of the pathovar-specific DNA fragments identified in this study encoded partial genes with orthologues in GAS and/or GBS. While the majority of GAS-related DNA fragments were identified as being bacteriophage related (18, 19), the majority of the pathovar-specific GBS orthologues were related to an uncharacterized MGE found in GBS serotype V (2603V/R) (52). Through a combination of long PCR, primer walking, and adapter PCR, we determined the full nucleotide sequence of this putative MGE in NS3396. ICESde3396 was found to be approximately 64 kb in size and is predicted to contain 66 ORFs (Table 3). Only 38 of the ORFs are also found in the putative ICE in the GBS 2603V/R genome that we have designated ICESa2603 (Fig. 1). The shared ORFs encode proteins involved in conjugal processes and include a site-specific tyrosine-like recombinase, relaxases, bacterial mobilization proteins, and TraG.

TABLE 3.

Features and predicted ORF functions of ICESde3396

| ORF | Position (bp)

|

No. of aa | Direction of DNA strand | % G/C content | % aa identity | Species and gene no./locusf | Predicted function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | Stop | |||||||

| 1 | 1212 | 1 | 403 | − | 32.34 | 100 | SAG1247 | Site-specific recombinase (tyrosine-like) |

| 2 | 1450 | 1223 | 75 | − | 34.65 | 100 | SAG1248 | Hypothetical |

| 3 | 1953 | 1729 | 74 | − | 33.78 | 100 | SAG1249 | Transcriptional regulator, Cro/CI family |

| 4 | 3999 | 2134 | 621 | − | 32.05 | 99 | SAG1250 | Relaxase |

| 5 | 4351 | 3986 | 121 | − | 34.43 | 100 | SAG1251 | Bacterial mobilization protein (MobC) |

| 6 | 4720 | 4358 | 120 | − | 34.71 | 100 | SAG1252 | Hypothetical |

| 7 | 5043 | 5150 | 35 | + | 26.85 | 100 | SAJ_1275 | Hypothetical |

| 8 | 5211 | 5693 | 160 | + | 39.54 | 100 | SAJ_1276 | Hypothetical |

| 9 | 5534 | 5875 | 113 | + | 38.60 | 93a | S. suis 89/1591c | Transposase/integrase |

| 10 | 8279 | 6150 | 709 | − | 37.61 | 100 | SAG1257 | Probable cadmium efflux ATPase CadA |

| 11 | 8640 | 8272 | 122 | − | 33.60 | 99 | SAG1258 | Cadmium efflux system accessory protein CadC |

| 12 | 8843 | 9142 | 99 | + | 36.33 | 100 | SAG1259 | Hypothetical |

| 13 | 9984 | 9196 | 262 | − | 30.29 | 100 | SAG1260 | Hypothetical |

| 14 | 9990 | 10589 | 199 | + | 42.50 | 100 | SAG1261 | Hypothetical membrane-spanning protein |

| 15 | 12850 | 10763 | 695 | − | 43.92 | 98 | SAG1262 | Probable copper exporting ATPase TcrB-like |

| 16 | 13195 | 12989 | 68 | − | 36.23 | 98 | GBS 2603V/Rc,d | Copper-transporting ATPase TcrZ-like |

| 17 | 13819 | 13343 | 158 | − | 42.77 | 96a | SAG1263 | Copper-transporting ATPase TcrA-like |

| 18 | 14252 | 13806 | 148 | − | 36.24 | 92 | SAG1264 | Transcriptional repressor TcrY-like |

| 19 | 14460 | 14552 | 30 | + | 40.86 | ICESde3396_orf19 | ||

| 20 | 15048 | 14710 | 112 | − | 32.74 | 99 | SAI2183c | Cadmium efflux system accessory protein CadC |

| 21 | 15717 | 15061 | 218 | − | 33.49 | 99 | SAI2182c | Cadmium resistance protein CadD |

| 22 | 17311 | 15749 | 520 | − | 37.56 | 71 | M6_Spy1124 | Site-specific recombinase |

| 23 | 18222 | 17311 | 303 | − | 37.50 | 67 | M6_Spy1125 | Site-specific recombinase |

| 24 | 18499 | 18338 | 53 | − | 30.86 | 58 | Tn1207.3orf55 | Phage lysin |

| 25 | 20077 | 18608 | 489 | − | 43.06 | 59 | SAM_0643 | Amidase/phage cell wall hydrolase |

| 26 | 20479 | 20084 | 131 | − | 34.09 | 66a | SAM_0642 | Holin |

| 27 | 20663 | 20457 | 68 | − | 36.71 | ICESde3396_orf27 | ||

| 28 | 21300 | 21659 | 119 | + | 30.83 | 99 | L. innocua pli0060c | Cadmium efflux system accessory protein CadC |

| 29 | 21656 | 23773 | 705 | + | 37.11 | 100 | L. innocua pli0061c | Cadmium efflux ATPase CadA |

| 30 | 24476 | 24706 | 76 | + | 32.47 | ICESde3396_orf30 | ||

| 31 | 25589 | 24819 | 256 | − | 32.94 | 90 | E. faecalis V583 EF3208c | Inner membrane transport permease YadH-like |

| 32 | 26517 | 25582 | 311 | − | 35.69 | 97a | L. innocua pli0041 | ABC transporter, ATP subunit YadG-like |

| 33 | 26782 | 26672 | 36 | − | 35.14 | 99d | L. innocua pLI100 | NDb |

| 34 | 28480 | 26807 | 557 | − | 37.51 | 99 | L. innocua pli0040 | Coenzyme A disulfide reductase LpdA |

| 35 | 28713 | 28501 | 70 | − | 37.09 | 100a | L. innocua pli0039 | Arsenical resistance protein ACR3-like (ArsB) |

| 36 | 30510 | 28768 | 580 | − | 37.81 | 99 | L. innocua pli0037 | Arsenical pump-driving ATPase ArsA |

| 37 | 30893 | 30546 | 115 | − | 36.21 | 98 | L. innocua pli0036 | Arsenical resistance repressor ArsR |

| 38 | 31398 | 31027 | 123 | − | 38.98 | 98 | L. innocua pli0035 | Arsenical resistance trans-acting repressor ArsD |

| 39 | 31666 | 31400 | 88 | − | 32.96 | 98 | L. innocua pli0034 | Arsenical resistance repressor ArsR |

| 40 | 32558 | 31875 | 227 | − | 37.43 | 98 | L. innocua pli0032 | Transposase (IS1216) |

| 41 | 33200 | 32841 | 119 | − | 34.17 | 77 | SAG1273 | Hypothetical |

| 42 | 33576 | 33187 | 129 | − | 36.15 | 97 | SAG1274 | Hypothetical |

| 43 | 33800 | 33573 | 75 | − | 38.60 | 96 | SAG1275 | Hypothetical |

| 44 | 34930 | 33854 | 358 | − | 38.25 | 91 | SAG1276 | Hypothetical zinc finger protein |

| 45 | 35608 | 34970 | 212 | − | 39.44 | 95 | SAI1373 | Hypothetical |

| 46 | 35994 | 35704 | 96 | − | 32.30 | 91 | SAG1278 | Hypothetical |

| 47 | 36307 | 36008 | 99 | − | 42.33 | 84 | SAG1279 | Hypothetical |

| 48 | 43214 | 36378 | 2278 | − | 41.00 | 99 | SAG1280 | SNF2-related helicase |

| 49 | 43802 | 43251 | 183 | − | 38.04 | 100 | SAG1281 | Hypothetical |

| 50 | 43977 | 43786 | 63 | − | 42.71 | 100 | SAG1282 | Calcium-binding protein |

| 51 | 46772 | 46882 | 36 | + | 41.44 | 100d | GBS 2603V/R | ND |

| 52 | 48873 | 43978 | 1631 | − | 41.71 | 99 | SAG1283 | Agglutinin receptor precursor |

| 53 | 49140 | 49742 | 200 | + | 34.66 | 100 | SAG1284 | Abortive infection protein AbiGI |

| 54 | 49739 | 50584 | 281 | + | 31.80 | 100 | SAG1285 | Abortive infection protein AbiGII |

| 55 | 53471 | 50670 | 933 | − | 42.68 | 93 | SAG1286 | N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase |

| 56 | 55824 | 53473 | 783 | − | 40.43 | 99 | SAG1287 | Hypothetical |

| 57 | 57050 | 56196 | 284 | − | 41.75 | 99 | SAG1289 | Hypothetical |

| 58 | 57323 | 57069 | 84 | − | 44.31 | 100 | SAG1290 | Hypothetical |

| 59 | 59146 | 57329 | 605 | − | 40.98 | 99 | SAG1291 | Conjugal transfer protein TraG |

| 60 | 59670 | 59146 | 174 | − | 39.24 | 99 | SAG1292 | Hypothetical |

| 61 | 60301 | 59711 | 196 | − | 39.26 | 100 | SAG1293 | Putative protease |

| 62 | 60537 | 60298 | 79 | − | 35.42 | 100 | SAG1294 | Hypothetical |

| 63 | 60929 | 60540 | 129 | − | 41.03 | 100 | SAG1295 | Hypothetical (potential arsenate reductase) |

| 64 | 61362 | 60934 | 142 | − | 38.46 | 100 | SAG1296 | Hypothetical |

| 65 | 62701 | 61346 | 451 | − | 44.32 | 99 | SAG1297 | DNA methylase |

| 66 | 63668 | 62849 | 272 | − | 40.42 | 100 | SAG1299 | Replication initiator |

Proteins with partial homology to the GenBank database that may represent truncated proteins through a frameshift or deletion events.

ORFs with less than 35% amino acid identity to the GenBank database are defined as having no database homologue (ND).

These ORFs had equal identity to multiple ORFs from the same/different isolate(s).

Homology is based on BlastN analysis and represents a nonannotated ORF in the GenBank database.

e aa, amino acid(s).

Streptococcal species unless indicated otherwise.

ICESde3396 and ICESa2603 also share a number of genes predicted to encode putative virulence factors. These include the abortive infection genes abiGI and abiGII which have a role in lactococcal phage exclusion (13), a putative surface-associated agglutinin receptor which may modulate adherence of streptococci to oral sites through binding of salivary agglutinin (7, 52), and several genes predicted to encode proteins conferring resistance to cadmium and copper. Like their lactococcal homologues, the abiGI and abiGII genes of ICESde3396 and ICESa2603 exhibit a lower percent GC content (31% and 34.6%, respectively) than GGS and GBS genomes (and the respective surrounding DNA within the ICE), suggesting that they were acquired by the ICE through LGT (38).

Mosaic structure of an 18-kb region unique to ICESde3396.

The defining difference between ICESde3396 and ICESa2603 is the presence of an 18-kb internal region within ICESde3396 (Fig. 1). The region encodes 21 ORFs (ICESde3396orf19 to -orf40) and is flanked by a small ORF with limited similarity to a transposase (Tn1545) at one end,and a second putative transposase associated with the insertion sequence IS1216 at the other. When the genes in this region were compared to those in the GenBank database, it became apparent that this region consists of four clusters whose orthologues are found in unrelated bacterial species, including nonstreptococcal species (Fig. 1).

The first of these clusters contains two genes from a cadmium resistance operon, cadC (ICESde3396_orf20) and cadD (ICESde3396_orf21), which is found in all GAS genomes, in some but not all GBS genomes, and in Streptococcus gordonii and Streptococcus parasanguinis. cadD orthologues (but not cadC) are also found in Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The five genes in the second cluster are predicted to encode two putative recombinases, a truncated lysin, a cell wall hydrolase, and holin with similarity at the amino acid level to ORFs from a GAS bacteriophage (3, 4) and GBS MGE. The low amino acid sequence identity (<70%) and absence of significant nucleotide sequence homology suggest a distant evolutionary relationship between these orthologues. The third cluster (ICESde3396_orf28 and ICESde3396_orf29) encodes a second cadmium resistance operon lacking any sequence homology to the previously described cadmium resistance operon. The orthologues of this operon are found on plasmids from Listeria innocua (pLI100) and Lactococcus lactis (50) and a genomic island from Streptococcus thermophilus (40). The final cluster contains genes whose orthologues are found in a different region of the pLI100 plasmid. These include genes from a yadG- and yadH-like operon that also has orthologues in Enterococcus faecalis. The remaining seven genes of this cluster form a putative arsenic resistance operon. While the overall amino acid identity between the ORFs in this operon and their corresponding homologues from pLI100 is high (>98%), a truncation in the purported arsenic transporter (ArsB) and absence of an ArsC homologue suggests the operon is nonfunctional.

To provide a better understanding of how this recombinogenic region may have evolved, we undertook a genomic examination of each of the four clusters and surrounding DNA in their purported progenitor chromosomes. In each case, the cluster was situated in close proximity to MGE-associated genes, suggesting that incorporation of these elements into ICESde3396 has occurred through standard LGT (Fig. 1). The observation that the individual clusters (e.g., the two cadmium clusters) are also present in other unrelated bacterial species provides further support for the role of MGEs in their lateral dissemination.

The chromosomal location of ICESde3396 is conserved.

In order to determine the flanking region of ICESde3396 in NS3396, adaptor PCRs using proximal ICESde3396-specific primers in conjunction with an adaptor-specific primer were performed (43). Sequencing of the PCR products flanking ICESde3396_orf66 identified two genes. The first of these genes encodes a small ORF with significant homology to a small hypothetical protein (SAG1300) adjacent to ICESa2603 in the 2603V/R genome (52). The second ORF was homologous to the 50s ribosomal gene L7/L12 and is also found in proximity to ICESa2603. Subsequent PCR analysis confirmed that the 50s ribosomal L7/L12 gene flanked the ICEs in all ICE-positive GGS and GBS strains examined in this study (data not shown). The similar flanking sequences suggested that integration occurs via a specific mechanism common to the tyrosine family of recombinases (8).

Distribution of ICESde3396 and ICESa2603 in β-hemolytic streptococci.

The presence of ICESde3396-like and ICESa2603-like elements in other GGS, GBS, and GAS strains was examined using PCR that targeted three independent regions of ICESde3396 (Fig. 1). The first product (R1) extended from ICESde3396_orf1 to ICESde3396_orf5. The second product (R2) extended from ICESde3396_orf17 to ICESde3396_orf23 and includes DNA common to both ICESde3396 and ICESa2603, as well as DNA unique to ICESde3396 (i.e., the 18-kb chimeric region). Amplification of this fragment enabled this differentiation between strains harboring ICESde3396-like and ICESa2603-like MGEs and also confirmed the proximal locations of these regions in ICESde3396-like ICEs. The third fragment (R3) spanned ICESde3396_orf55 to ICESde3396_orf61.

Of the 69 β-hemolytic isolates screened, 11 were positive for all three regions (i.e., R1+ R2+ R3+), implying that they possessed ICESde3396-like elements (Table 4). Four of the 11 positive isolates were GGS, and the remainder were GBS. Another four isolates (three GGS and one GBS) possessed both the R1 and R3 regions but lacked the R2 region (i.e., R1+ R2− R3+), suggesting that they harbored ICESa2603-like elements. The difference in the proportion of strains that were R1+ R2+ R3+ or R1+ R2− R3+ was not found to be statistically significant, as determined by Fisher's exact test. The diagnostic PCR also identified nine GGS isolates, and one GBS isolate possessed at least one of the three regions used to determine the presence of the ICEs but did not conform to the PCR profile used to define ICESde3396-like (R1+ R2+ R3+) or ICESa2603-like (R1+ R2− R3+) elements. Of note, none of the GAS isolates screened were positive for any of the three regions.

TABLE 4.

Distribution of R1, R2, and R3 regions in GGS, GBS, and GAS isolates

| Regionsa | GGS (n = 30) | GBS (n = 19) | GAS (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1− R2− R3− | 15 | 10 | 20 |

| R1+ R2+ R3+ | 4 | 7 | 0 |

| R1+ R2− R3+ | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| R1+ R2+ R3V | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| R1− R2+ R3+ | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| R1− R2− R3+ | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| R1+ R2+ R3− | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| R1+ R2V R3− | 0 | 1 | 0 |

V, a PCR product was generated for this region. However, the size of this product differed from that observed for the corresponding fragment in ICESde3396.

ICESde3396 confers resistance to cadmium and arsenate.

To test whether the metal resistance operons identified within ICESde3396 were functional, NS3396 (R1+ R2+ R3+), GGS10 (R1− R2− R3−), GBS RBH01 (R1+ R2+ R3+), and GBS RBH03 (R1− R2− R3−) were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with increasing concentrations of sodium(III) arsenite, sodium(V) arsenate, copper chloride, or cadmium chloride, and optical density of the cultures was measured at regular intervals. Whereas growth of GGS10 was inhibited by 1 mM arsenate, both NS3396 and GBS RBH01 showed little or no growth inhibition in 5 mM arsenate. In contrast to the ICE-lacking strains, both ICE-positive strains possessed an increased tolerance to cadmium at concentrations below 1 mM (Fig. 2). No association between the presence of ICE3396-like elements and arsenite or copper resistance was observed.

FIG. 2.

Growth of GGS and GBS in the presence of arsenate, arsenite, cadmium, and copper. GGS strains are represented by squares and GBS strains by triangles. Closed symbols represent isolates containing ICESde3396 or ICE ICESde3396-like elements (i.e., R1+ R2+ R3+). Open symbols represent ICESde3396-negative strains (i.e., R1− R2− R3−). Strains were grown overnight in Todd-Hewitt broth, harvested, and resuspended medium containing increasing concentrations of sodium arsenate, sodium arsenite, cadmium chloride, or copper chloride. The OD600 of cultures was measured at regular intervals during the growth cycle. Data is presented is the OD600 after 24 h of growth in the presence of cadmium and 5 h of growth in the presence of arsenite, arsenate, and copper.

To provide additional support for a correlation between the tolerance to cadmium and arsenate and the presence of ICESde3396-like elements, additional GGS and GBS strains that were R1+ R2+ R3+, R1+ R2− R3+, or R1− R2− R3− were grown in the presence of 3 mM arsenate or 0.4 mM cadmium chloride (Fig. 3). Four of the five R1+ R2+ R3+ isolates were capable of growing in 3 mM arsenate. In contrast, none of the R1+ R2− R3+ isolates were able to grow in the presence of arsenate. With the exception of a single strain, all ICE-harboring isolates were also able to grow in the presence of cadmium. None of the six ICE-negative strains grew in the presence of arsenate or cadmium.

FIG. 3.

ICESde3396 is associated with increased resistance to arsenate and cadmium. GGS and GBS were grown in the presence of 3 mM sodium arsenate (A) or 0.4 mM cadmium chloride. (B) Black bars represent isolates containing ICESde3396-like elements (i.e., R1+ R2+ R3+). Gray bars represent isolates containing ICESa2603-like elements (i.e., R1+ R2+ R3+). Open bars represent ICESde3396-negative strains (i.e., R1− R2− R3−). Data is presented as the OD600 after 5 h of growth in the presence of arsenate and 24 h of growth in the presence of cadmium.

ICESde3396 is transferable to other β-hemolytic streptococci.

As the nucleotide sequence data suggested that ICESde3396 has the full complement of genes necessary for conjugation, we next investigated whether we could transfer this element to other β-hemolytic streptococci. To do so we marked ICESde3396 by replacing a 1.5-kb segment within the 18-kb recombinogenic region with a gene conferring kanamycin resistance. We reasoned that as the18-kb recombinogenic region was absent in ICESa2603, it would not contain any genes necessary for conjugal processes. After filter mating between NS3396 ICESde3396:Km and GGS10, doubly antibiotic-resistant GGS recipients (i.e., kanamycin and streptomycin resistant) were observed on Todd-Hewitt agar, suggesting that transfer of the ICE had occurred. Subsequently, we successfully transferred the ICE to GAS NS344 and GBS RBH05. The frequency of mobilization of ICESde3396:Km into GGS, GBS, and GAS was found to be 2 × 10−4, 6 × 10−6, and 1.5 × 10−3, respectively. Compared to their parental strains, all transconjugants were also found to have increased tolerance to arsenate and cadmium (Fig. 4). As the kanamycin resistance marker was incorporated into the 18-kb recombinogenic region, it was conceivable that this region alone may be incorporated into recipient strains through the resident IS1216 transposase. To test for this possibility, five GAS, GBS, and GGS transconjugants were chosen at random, and PCR analysis using the diagnostic primers specific for the genes in the R1, R2, and R3 regions was undertaken. All transconjugants tested possessed all three regions (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Growth of ICE3396-negative and ICE3396-positive transconjugants in the presence of 0.4 mM cadmium chloride and 3 mM sodium arsenate. Parental strains are represented by the open bars. Transconjugants harboring ICESde3396 are represented by black bars. Data is presented as the mean OD600 of cultures grown for 5 h in the presence of arsenate and 24 h in the presence of cadmium.

DISCUSSION

MGEs enable the nonvertical transfer of DNA between bacterial species. As such, they provide vehicles for rapid microbial adaptation and evolution. Previous studies have demonstrated MGEs are present in GAS, GBS, and GGS genomes and that many virulence factors are associated also with MGEs in these species (25, 45, 52). Bacteriophages are the most common MGE found in GAS genomes. All GAS strains analyzed to date have at least one prophage sequence, and most are polylysogenic (25). In contrast, bacteriophages appear to be much rarer in GBS and ICEs more prevalent. Without a genomic sequence, our understanding of the factors that influence genetic variation of GGS is less clear. Our previous study (18) identified a bacteriophage in NS3396 with significant homology to a bacteriophage from GAS. In the current study, we identified an ICE within the same GGS isolate that shares significant homology with a putative ICE in GBS. Thus, GGS appears capable of receiving and/or donating DNA to both these pathogenic species.

ICESde3396 carries genes whose orthologues can be found in numerous bacterial species, including GBS, GAS, S. parasanguinis, Streptococcus suis, Enterococcus spp., Lactococcus spp., Listeria spp., and Neisseria spp. Genetic analysis of the hypothesized progenitor chromosomes of the four independent clusters in the 18-kb recombinogenic region of ICESde3396 demonstrated that each was flanked by MGE-associated genes, indicating that the accumulation of these clusters within ICESde3396 occurs through typical LGT events. Additional transposase/integrases are also found in other parts of ICESde3396 and ICESa2603. An earlier study by Tettelin et al. suggested that both the GAS and GBS pangenomes were open (51). We hypothesize that as GGS is closely related to these species, its genome is also open, and that ICESde3396 is one element that contributes to the open genomes of β-hemolytic streptococci. The ICE serves as a repository for genes from diverse bacterial origins; incorporation of these genes within the ICE also prevents disruption of chromosomally encoded genes whose functions may be critical to bacterial fitness. Additionally, the ICE is a vehicle that enables dissemination of these newly acquired genes through the β-hemolytic population.

Our functional studies demonstrated that four of the five isolates harboring ICESde3396-like elements possessed an increased resistance to arsenate. Similarly, six of seven isolates harboring the ICESde3396-like or ICESa2603-like element had increased tolerances to cadmium. The association between the presence of the ICEs and tolerance to these metals and the fact that these tolerances were transferred to recipient strains provides strong evidence that these phenotypic properties are carried on the MGEs. We attribute the lack of cadmium resistance in GBS RBH02 and arsenate resistance in GGS MD048 to either ongoing modular evolution of the ICE or mutations resulting in a loss of phenotype. Modular evolution is a hallmark of all MGEs (28), and the cadmium resistance operon common to ICESde3396 and ICESa2603 lies adjacent to a putative transposase/integrase. Transposition events involving this element may have resulted in the loss or mutation of the cadmium operon region in GGS MD048. This is supported by the data demonstrating that the locus was amplifiable from ICESde3396 in NS3396 but not the ICE in MD048. The archetypal arsenic resistance operons contain three genes, arsR, arsB, and arsC (44). As the ars operon in the ICESde3396 includes a truncated arsB and lacks an arsC homologue, we were surprised to find the operon to be functional. As there is no apparent advantage to possession of this operon, further mutations accumulating in this region (deletions or point mutations) may eventually render the operon nonfunctional.

Although ICESde3396 does not carry antibiotic resistance genes, it does contain several genes whose homologues are found in other MGEs that do harbor antibiotic-resistant determinants, suggesting that transfer of DNA between these elements can occur. As an example, ICESde3396 contains homologues of genes found in a mefA carrying MGE in GAS 10394. More strikingly, a transposase associated with IS1216 is present at one end of the 18-kb chimeric region. IS1216 is part of a promiscuous insertion element that in other bacterial species carries genes conferring resistance to vancomycin (32, 39), erythromycin (32), and chloramphenicol (55). An IS1216 element from Enterococcus hirae also carries genes encoding a low affinity penicillin binding protein (42). Penicillin has remained the drug of choice for treatment and prevention of β-hemolytic infections for over 50 years. Unlike related bacteria, the β-hemolytic streptococci have not developed resistance to penicillin; the reasons for this remain unknown (31). As penicillin resistance has not arisen naturally in β-hemolytic streptococci, even in the face of long-term penicillin treatment, mutation of existing genes seems to be an unlikely source of future resistance. Rather, we speculate that transfer of penicillin resistance genes via an ICE is more likely to provide a mechanism for the acquisition of penicillin (or other antibiotic) resistance phenotypes. In this regard, tetracycline resistance genes linked to IS1216 have recently been reported in GGS (36). As antibiotic resistance increases in other bacterial species found in the same environmental niches occupied by β-hemolytic streptococci, the probability of transfer of antibiotic resistance determinants can only increase.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

After the manuscript was accepted, we found that RBH02 (Fig. 3) did not yield PCR products of any size. Consequently, its expected genotype is R1− R2− R3−, which in fact correlates with its resistance phenotype. This change does not affect our conclusions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Thanh Tran and Sean Mitchell for technical assistance. We thank the Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin, and the Department of Microbiology, Royal Brisbane Hospital, Brisbane, for the strains used in this study. We also thank Karen Taylor and Janelle Stirling for assistance with collection and curation of the QIMR GBS isolate collection.

This work was carried out with the financial support of the Australian Government's Cooperative Research Centre for Vaccine Technology and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Griffith Medical Research College is a joint program of Griffith University and the Queensland Institute of Medical Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 January 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aziz, R. K., R. A. Edwards, W. W. Taylor, D. E. Low, A. McGeer, and M. Kotb. 2005. Mosaic prophages with horizontally acquired genes account for the emergence and diversification of the globally disseminated M1T1 clone of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 1873311-3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks, D. J., S. B. Beres, and J. M. Musser. 2002. The fundamental contribution of phages to GAS evolution, genome diversification and strain emergence. Trends Microbiol. 10515-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks, D. J., S. F. Porcella, K. D. Barbian, S. B. Beres, L. E. Philips, J. M. Voyich, F. R. DeLeo, J. M. Martin, G. A. Somerville, and J. M. Musser. 2004. Progress toward characterization of the group A Streptococcus metagenome: complete genome sequence of a macrolide-resistant serotype M6 strain. J. Infect. Dis. 190727-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks, D. J., S. F. Porcella, K. D. Barbian, J. M. Martin, and J. M. Musser. 2003. Structure and distribution of an unusual chimeric genetic element encoding macrolide resistance in phylogenetically diverse clones of group A Streptococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 1881898-1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beres, S. B., and J. M. Musser. 2007. Contribution of exogenous genetic elements to the group A Streptococcus metagenome. PLoS ONE 2e800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bisno, A. L., F. A. Rubin, P. P. Cleary, and J. B. Dale. 2005. Prospects for a group A streptococcal vaccine: rationale, feasibility, and obstacles—report of a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases workshop. Clin. Infect. Dis. 411150-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady, L. J., D. A. Piacentini, P. J. Crowley, P. C. Oyston, and A. S. Bleiweis. 1992. Differentiation of salivary agglutinin-mediated adherence and aggregation of mutans streptococci by use of monoclonal antibodies against the major surface adhesin P1. Infect. Immun. 601008-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burrus, V., G. Pavlovic, B. Decaris, and G. Guedon. 2002. Conjugative transposons: the tip of the iceberg. Mol. Microbiol. 46601-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burrus, V., and M. K. Waldor. 2004. Shaping bacterial genomes with integrative and conjugative elements. Res. Microbiol. 155376-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carver, T. J., K. M. Rutherford, M. Berriman, M. A. Rajandream, B. G. Barrell, and J. Parkhill. 2005. ACT: the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics 213422-3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng, S., C. Fockler, W. M. Barnes, and R. Higuchi. 1994. Effective amplification of long targets from cloned inserts and human genomic DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 915695-5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chhatwal, G. S., D. J. McMillan, and S. R. Talay. 2006. Pathogenicity factors in Group C and G streptococci, p. 213-221. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 13.Chopin, M. C., A. Chopin, and E. Bidnenko. 2005. Phage abortive infection in lactococci: variations on a theme. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8473-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen-Poradosu, R., J. Jaffe, D. Lavi, S. Grisariu-Greenzaid, R. Nir-Paz, L. Valinsky, M. Dan-Goor, C. Block, B. Beall, and A. E. Moses. 2004. Group G streptococcal bacteremia in Jerusalem. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 101455-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cone, L. A., D. R. Woodard, P. M. Schlievert, and G. S. Tomory. 1987. Clinical and bacteriologic observations of a toxic shock-like syndrome due to Streptococcus pyogenes. N. Engl. J. Med. 317146-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies, M. R., D. J. McMillan, R. G. Beiko, V. Barroso, R. Geffers, K. S. Sriprakash, and G. S. Chhatwal. 2007. Virulence profiling of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis isolated from infected humans reveals 2 distinct genetic lineages that do not segregate with their phenotypes or propensity to cause diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 441442-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies, M. R., D. J. McMillan, G. H. Van Domselaar, M. K. Jones, and K. S. Sriprakash. 2007. Phage 3396 from a Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis pathovar may have its origins in Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 1892646-2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies, M. R., T. N. Tran, D. J. McMillan, D. L. Gardiner, B. J. Currie, and K. S. Sriprakash. 2005. Inter-species genetic movement may blur the epidemiology of streptococcal diseases in endemic regions. Microbes Infect. 71128-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delvecchio, A., B. J. Currie, J. D. McArthur, M. J. Walker, and K. S. Sriprakash. 2002. Streptococcus pyogenes prtFII, but not sfbI, sfbII or fbp54, is represented more frequently among invasive-disease isolates of tropical Australia. Epidemiol. Infect. 128391-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dermer, P., C. Lee, J. Eggert, and B. Few. 2004. A history of neonatal group B streptococcus with its related morbidity and mortality rates in the United States. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 19357-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efstratiou, A. 1997. Pyogenic streptococci of Lancefield groups C and G as pathogens in man. Soc. Appl. Bacteriol. Symp. Ser. 26S72-S79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ekelund, K., P. Skinhoj, J. Madsen, and H. B. Konradsen. 2005. Invasive group A, B, C and G streptococcal infections in Denmark 1999-2002: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11569-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Facklam, R. 2002. What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15613-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferretti, J. J., D. Ajdic, and W. M. McShan. 2004. Comparative genomics of streptococcal species. Indian J. Med. Res. 119(Suppl.)1-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferretti, J. J., W. M. McShan, D. Ajdic, D. J. Savic, G. Savic, K. Lyon, C. Primeaux, S. Sezate, A. N. Suvorov, S. Kenton, H. S. Lai, S. P. Lin, Y. Qian, H. G. Jia, F. Z. Najar, Q. Ren, H. Zhu, L. Song, J. White, X. Yuan, S. W. Clifton, B. A. Roe, and R. McLaughlin. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 984658-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franken, C., G. Haase, C. Brandt, J. Weber-Heynemann, S. Martin, C. Lammler, A. Podbielski, R. Lutticken, and B. Spellerberg. 2001. Horizontal gene transfer and host specificity of beta-haemolytic streptococci: the role of a putative composite transposon containing scpB and lmb. Mol. Microbiol. 41925-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frost, L. S., R. Leplae, A. O. Summers, and A. Toussaint. 2005. Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3722-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaviria, J. M., and A. L. Bisno. 2000. Group C and G streptococci, p. 238-254. In D. L. Stevens and E. L. Kaplan (ed.), Streptococcal infections: clinical aspects, microbiology, and molecular pathogenesis. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 30.Hindsholm, M., and H. C. Schønheyder. 2002. Clinical presentation and outcome of bacteraemia caused by beta-haemolytic streptococci serogroup G. APMIS 110554-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horn, D. L., J. B. Zabriskie, R. Austrian, P. P. Cleary, J. J. Ferretti, V. A. Fischetti, E. Gotschlich, E. L. Kaplan, M. McCarty, S. M. Opal, R. B. Roberts, A. Tomasz, and Y. Wachtfogel. 1998. Why have group A streptococci remained susceptible to penicillin? Report on a symposium. Clin. Infect. Dis. 261341-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen, L. B., A. M. Hammerum, and F. M. Aarestrup. 2000. Linkage of vat(E) and erm(B) in streptogramin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates from Europe. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 442231-2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalia, A., M. C. Enright, B. G. Spratt, and D. E. Bessen. 2001. Directional gene movement from human-pathogenic to commensal-like streptococci. Infect. Immun. 694858-4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Laupland, K. B., T. Ross, D. L. Church, and D. B. Gregson. 2006. Population-based surveillance of invasive pyogenic streptococcal infection in a large Canadian region. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12224-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawrence, J. G. 1997. Selfish operons and speciation by gene transfer. Trends Microbiol. 5355-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, L. C., J. C. Tsai, P. R. Hsueh, S. P. Tseng, W. C. Hung, H. J. Chen, and L. J. Teng. 2008. Identification of tet(S) gene area in tetracycline-resistant Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61453-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMillan, D. J., R. Geffers, J. Buer, B. J. Vlaminckx, K. S. Sriprakash, and G. S. Chhatwal. 2007. Variations in the distribution of genes encoding virulence and extracellular proteins in group A streptococcus are largely restricted to 11 genomic loci. Microbes Infect. 9259-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Connor, L., A. Coffey, C. Daly, and G. F. Fitzgerald. 1996. AbiG, a genotypically novel abortive infection mechanism encoded by plasmid pCI750 of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris UC653. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 623075-3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulsen, I. T., L. Banerjei, G. S. Myers, K. E. Nelson, R. Seshadri, T. D. Read, D. E. Fouts, J. A. Eisen, S. R. Gill, J. F. Heidelberg, H. Tettelin, R. J. Dodson, L. Umayam, L. Brinkac, M. Beanan, S. Daugherty, R. T. DeBoy, S. Durkin, J. Kolonay, R. Madupu, W. Nelson, J. Vamathevan, B. Tran, J. Upton, T. Hansen, J. Shetty, H. Khouri, T. Utterback, D. Radune, K. A. Ketchum, B. A. Dougherty, and C. M. Fraser. 2003. Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science 2992071-2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavlovic, G., V. Burrus, B. Gintz, B. Decaris, and G. Guedon. 2004. Evolution of genomic islands by deletion and tandem accretion by site-specific recombination: ICESt1-related elements from Streptococcus thermophilus. Microbiology 150759-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez-Casal, J., J. A. Price, E. Maguin, and J. R. Scott. 1993. An M protein with a single C repeat prevents phagocytosis of Streptococcus pyogenes: use of a temperature-sensitive shuttle vector to deliver homologous sequences to the chromosome of S. pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 8809-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raze, D., O. Dardenne, S. Hallut, M. Martinez-Bueno, J. Coyette, and J. M. Ghuysen. 1998. The gene encoding the low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 3r in Enterococcus hirae S185R is borne on a plasmid carrying other antibiotic resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42534-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers, Y. C., A. C. Munk, L. J. Meincke, and C. S. Han. 2005. Closing bacterial genomic sequence gaps with adaptor-PCR. BioTechniques 3931-32, 34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosen, B. P. 1999. Families of arsenic transporters. Trends Microbiol. 7207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sitkiewicz, I., M. J. Nagiec, P. Sumby, S. D. Butler, C. Cywes-Bentley, and J. M. Musser. 2006. Emergence of a bacterial clone with enhanced virulence by acquisition of a phage encoding a secreted phospholipase A2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10316009-16014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith, M. D., and W. R. Guild. 1980. Improved method for conjugative transfer by filter mating of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 144457-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevens, D. L., M. H. Tanner, J. Winship, R. Swarts, K. M. Ries, P. M. Schlievert, and E. Kaplan. 1989. Severe group A streptococcal infections associated with a toxic shock-like syndrome and scarlet fever toxin A. N. Engl. J. Med. 3211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sumby, P., S. F. Porcella, A. G. Madrigal, K. D. Barbian, K. Virtaneva, S. M. Ricklefs, D. E. Sturdevant, M. R. Graham, J. Vuopio-Varkila, N. P. Hoe, and J. M. Musser. 2005. Evolutionary origin and emergence of a highly successful clone of serotype M1 group A Streptococcus involved multiple horizontal gene transfer events. J. Infect. Dis. 192771-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sylvetsky, N., D. Raveh, Y. Schlesinger, B. Rudensky, and A. M. Yinnon. 2002. Bacteremia due to beta-hemolytic Streptococcus group G: increasing incidence and clinical characteristics of patients. Am. J. Med. 112622-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanous, C., E. Chambellon, and M. Yvon. 2007. Sequence analysis of the mobilizable lactococcal plasmid pGdh442 encoding glutamate dehydrogenase activity. Microbiology 1531664-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tettelin, H., V. Masignani, M. J. Cieslewicz, C. Donati, D. Medini, N. L. Ward, S. V. Angiuoli, J. Crabtree, A. L. Jones, A. S. Durkin, R. T. Deboy, T. M. Davidsen, M. Mora, M. Scarselli, I. Margarit y Ros, J. D. Peterson, C. R. Hauser, J. P. Sundaram, W. C. Nelson, R. Madupu, L. M. Brinkac, R. J. Dodson, M. J. Rosovitz, S. A. Sullivan, S. C. Daugherty, D. H. Haft, J. Selengut, M. L. Gwinn, L. Zhou, N. Zafar, H. Khouri, D. Radune, G. Dimitrov, K. Watkins, K. J. O'Connor, S. Smith, T. R. Utterback, O. White, C. E. Rubens, G. Grandi, L. C. Madoff, D. L. Kasper, J. L. Telford, M. R. Wessels, R. Rappuoli, and C. M. Fraser. 2005. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10213950-13955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tettelin, H., V. Masignani, M. J. Cieslewicz, J. A. Eisen, S. Peterson, M. R. Wessels, I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, I. Margarit, T. D. Read, L. C. Madoff, A. M. Wolf, M. J. Beanan, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. DeBoy, A. S. Durkin, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, N. B. Fedorova, D. Scanlan, H. Khouri, S. Mulligan, H. A. Carty, R. T. Cline, S. E. Van Aken, J. Gill, M. Scarselli, M. Mora, E. T. Iacobini, C. Brettoni, G. Galli, M. Mariani, F. Vegni, D. Maione, D. Rinaudo, R. Rappuoli, J. L. Telford, D. L. Kasper, G. Grandi, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Complete genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of an emerging human pathogen, serotype V Streptococcus agalactiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9912391-12396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Domselaar, G. H., P. Stothard, S. Shrivastava, J. A. Cruz, A. Guo, X. Dong, P. Lu, D. Szafron, R. Greiner, and D. S. Wishart. 2005. BASys: a web server for automated bacterial genome annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 33W455-W459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walker, M. J., A. Hollands, M. L. Sanderson-Smith, J. N. Cole, J. K. Kirk, A. Henningham, J. D. McArthur, K. Dinkla, R. K. Aziz, R. G. Kansal, A. J. Simpson, J. T. Buchanan, G. S. Chhatwal, M. Kotb, and V. Nizet. 2007. DNase Sda1 provides selection pressure for a switch to invasive group A streptococcal infection. Nat. Med. 13981-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Werner, G., B. Hildebrandt, I. Klare, and W. Witte. 2000. Linkage of determinants for streptogramin A, macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B, and chloramphenicol resistance on a conjugative plasmid in Enterococcus faecium and dissemination of this cluster among streptogramin-resistant enterococci. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290543-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams, G. S. 2003. Group C and G streptococci infections: emerging challenges. Clin. Lab Sci. 16209-213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang, H. C., J. Cheng, T. M. Finan, B. P. Rosen, and H. Bhattacharjee. 2005. Novel pathway for arsenic detoxification in the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 1876991-6997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang, S., N. M. Green, I. Sitkiewicz, R. B. Lefebvre, and J. M. Musser. 2006. Identification and characterization of an antigen I/II family protein produced by group A Streptococcus. Infect. Immun. 744200-4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]