Abstract

Assembly of many RNA viruses entails the encapsidation of multiple genome segments into a single virion, and underlying mechanisms for this process are still poorly understood. In the case of the nodavirus Flock House virus (FHV), a bipartite positive-strand RNA genome consisting of RNA1 and RNA2 is copackaged into progeny virions. In this study, we investigated whether the specific packaging of FHV RNA is dependent on an arginine-rich motif (ARM) located in the N terminus of the coat protein. Our results demonstrate that the replacement of all arginine residues within this motif with alanines rendered the resultant coat protein unable to package RNA1, suggesting that the ARM represents an important determinant for the encapsidation of this genome segment. In contrast, replacement of all arginines with lysines had no effect on RNA1 packaging. Interestingly, confocal microscopic analysis demonstrated that the RNA1 packaging-deficient mutant did not localize to mitochondrial sites of FHV RNA replication as efficiently as wild-type coat protein. In addition, gain-of-function analyses showed that the ARM by itself was sufficient to target green fluorescent protein to RNA replication sites. These data suggest that the packaging of RNA1 is dependent on trafficking of coat protein to mitochondria, the presumed site of FHV assembly, and that this trafficking requires a high density of positive charge in the N terminus. Our results are compatible with a model in which recognition of RNA1 and RNA2 for encapsidation occurs sequentially and in distinct cellular microenvironments.

The specific packaging of viral genomes is known to be dependent on high-affinity interactions between structural proteins and viral nucleic acid (21, 29, 36, 41, 45). Establishment of such interactions depends on close proximity of the two macromolecules, which, in turn, requires temporal and spatial coordination of the synthesis of the respective components during infection. To facilitate such coordination, many viruses establish special cellular compartments, or viral factories, in which processes such as genome replication and viral protein synthesis and assembly are intimately coupled (34, 59). An additional level of complexity is encountered in viruses whose genomes are split between multiple segments that have to be packaged into a single virion. Packaging configurations range from 2 segments for the positive-strand RNA genomes of nodaviruses (46) to 8 segments for the negative-strand influenza viruses (37) and 10 to 12 segments for the double-stranded RNA reoviruses (38). How these viruses package all segments into a single virion with exquisite specificity is still a mystery, and it is possible that different mechanisms are used to this end. In this study we investigated packaging of the bipartite genome of the nodavirus flock house virus (FHV).

The genome of FHV consists of RNA1 (3.1 kb) and RNA2 (1.4 kb), which are copackaged into a capsid that has T=3 icosahedral symmetry (8, 10, 23, 49). RNA1 encodes the 112-kDa RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), which is targeted to outer mitochondrial membranes for the establishment of RNA replication complexes (20, 30, 31). RNA2 encodes the 43-kDa coat precursor protein α, which is the only structural protein required for assembly (12, 13). During assembly, 180 copies of protein α assemble around RNA1 and RNA2 to form a noninfectious provirion intermediate, which acquires infectivity by spontaneous cleavage of protein α into proteins β (38 kDa) and γ (5 kDa) (13, 47). Both cleavage products remain associated with the mature FHV virion.

FHV replicates its genome on outer mitochondrial membranes (31). The N-terminal 46 amino acids of the RdRp represent a targeting signal that contains charge properties similar to those of other cellular mitochondrial membrane proteins (19, 25, 30). This suggests that general cellular mechanisms for mitochondrial association are exploited for the integration of RdRp into this specific location. Such mechanisms are reliant on certain molecular chaperones, both for the posttranslational stabilization of proteins and for the targeting of these proteins to mitochondrial membranes (16, 55). Subsequent to membrane integration, FHV RdRp induces the formation of membrane invaginations comprising 50- to 70-nm spherical structures, whose architecture and organization have recently been studied in exquisite detail by electron microscope (EM) tomography (20). Several observations suggest that RNA replication occurs in spherules and include the detection of both RdRp and viral RNA within these spherules via immuno-EM (20, 31).

In contrast to RdRp, FHV coat protein does not contain any obvious subcellular targeting signals, and studies relevant to the localization of this protein are limited to the presence of cytoplasmic virus particle aggregates that are readily detectable by EM in nodavirus-infected cells (1, 26). Results from our laboratory showing that coat protein translation from replicating RNA is tightly coupled to specific genome recognition suggest that FHV assembly takes place in close proximity to the mitochondrial RNA replication complexes (57).

High-resolution structural studies of FHV particles has shown that the N and C termini of the coat protein are located inside the particle in close proximity to the RNA. Although they are largely disordered in the crystal structure, direct interactions with the phosphodiester backbone of the packaged RNA are observed for lysine residue 68 at the N terminus and lysine residues 371 and 375 at the C terminus (10). We previously reported that both the C terminus and N terminus play critical roles in specific packaging of FHV RNAs. Deletion of C-terminal residues 382 to 407 results in packaging of random cellular RNA (45), whereas deletion of N-terminal residues 2 to 31 results in inefficient packaging of RNA2 but normal packaging of RNA1 (29). The latter result indicates that the FHV coat protein recognizes the two genomic segments independently of each other and that a separate region of the protein is used for selection of RNA1. A likely candidate for such a region comprises residues 32 to 50, which is highly basic due to the presence of 12 arginine residues. We refer to this region as the arginine-rich motif (ARM). Here, we show that the ARM is indeed required for specific packaging of RNA1. However, the underlying mechanism does not appear to be based on a specific interaction between the ARM and a recognition motif on RNA1. Instead, confocal microscopic analyses suggest that the ARM is required for trafficking of coat protein to mitochondria, the presumed site of FHV assembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Drosophila melanogaster DL-1 and S2 cells were propagated as monolayers in Schneider's insect medium supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 27°C, as described previously (12).

Antibodies and fluorescence reagents.

Monoclonal mouse antibodies to FHV RdRp were a generous gift from Paul G. Ahlquist from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. KDEL monoclonal antibodies for the detection of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident proteins such as BiP containing the KDEL sequence were from Stressgen, while monoclonal mouse antibodies to α-tubulin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. MitoTracker Red CM-H2Xros, Alexa Fluor 555-phalloidin, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and all secondary immunoreagents were from Invitrogen.

Plasmids.

To generate the coat protein mutants described in this study, overlap extension PCR was used to introduce various mutations in the coding sequence of this protein on a previously described plasmid called p2BS(+)-wt (where wt is wild type) (18, 47). All of these mutations were made to the sequence encoding the ARM and involved either amino acid substitutions or replacement of the ARM with the ARM of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Rev protein. A previously described plasmid called pDIeGFP was modified to facilitate the generation of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) fusion constructs described in this study. pDIeGFP contains the eGFP coding sequence inserted into a SacI site near the 5′ end of the cDNA of an RNA2-derived defective interfering RNA (DI RNA) called DI-634 (7). This plasmid encodes residues 1 to 13 of coat protein followed by eGFP and the C-terminal portion of a 149-residue polypeptide encoded by DI-634. To avoid any undesirable effects of this polypeptide on the subcellular trafficking of fusion proteins, a stop codon was introduced directly behind the eGFP reading frame via PCR. Using overlap extension PCR, the residual coat protein sequence upstream of eGFP was either removed to generate a DNA fragment encoding eGFP or replaced with that of residues 1 to 46 of FHV RdRp to generate a DNA fragment encoding mutant eGFP (eGFP-M). The respective fragments were digested with EcoRI and XbaI and used to replace a corresponding restriction fragment containing FHV RNA2 cDNA in plasmid pF2000, which was constructed using the pGEM-T Easy vector system (Promega). The resultant plasmid encoding untagged eGFP was designated pF2001 and used as a parental vector for the generation of the fusion protein eGFP-4. In accordance, a DNA fragment encoding eGFP with an N-terminal tag comprising residues 32 to 50 of coat protein was generated by overlap extension PCR, digested with EcoRI and SacI, and used to replace the corresponding restriction fragment in pF2001. A similar cloning strategy was use to generate constructs for eGFP-1, eGFP-2, and eGFP-3, with the exception that PCR products were digested with SacI and ligated into the corresponding restriction site in a previously described plasmid containing DI-634 cDNA (61). All constructs used in this study were subjected to DNA sequencing to confirm that no errors were introduced by PCR.

Preparation of RNA for liposome-mediated transfection.

Capped RNA transcripts encoding wt and mutant coat proteins, as well as eGFP fusion proteins, were synthesized by in vitro transcription from XbaI-linearized plasmids as described previously (45). Total Drosophila cell RNA containing RNA1 served as a source of RNA1 for liposome-mediated transfection. A technique for the preparation of this RNA has been described previously (45).

Transfection/infection of Drosophila cells.

A previously described transfection/infection protocol was used for the expression of wt and mutant coat proteins (29). In brief, capped RNA2 transcripts were transfected together with a total cellular RNA extract containing RNA1 into 1 × 107 DL-1 cells using Cytofectene (Bio-Rad). After a 20- to 22-h incubation period at 27°C, the cells were subjected to freeze-thaw lysis. Cell debris was pelleted by low-speed centrifugation, and the particles within the supernatant were used to infect 5 × 107 cells. Incubation at 27°C was continued up to 48 h postinfection (hpi).

Purification of virus particles.

A previously described method was used for the purification of FHV particles from Drosophila cells (29). In brief, cells were lysed in 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and cell debris was pelleted at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Particles in the resultant supernatant were treated with 10 μg/ml RNase A for 30 min and pelleted through a 30% (wt/wt) sucrose cushion. The resuspended pellet represented a partially purified FHV preparation that was either evaluated for virus yield by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis or subjected to additional purification by sedimentation though a 10 to 40% (wt/wt) sucrose gradient. Sucrose gradients were fractionated using an ISCO gradient fractionator at 0.75 ml/min and 0.5 min/fraction. In some instances, particles were harvested from these gradients by needle puncture.

RNA analysis.

Total Drosophila cell RNA was extracted using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen), and packaged RNA was extracted from purified FHV particles by means of phenol-chloroform extraction as described previously (45). To confirm that mutagenized viral RNAs within total cell RNA extracts were free of any back mutations, reverse transcription-PCR was performed on these extracts using a OneStep RT-PCR kit (Qiagen), and the resultant PCR products were sequenced. The forward and reverse primers that were used corresponded to nucleotides 1 to 18 and 488 to 468 of RNA2, respectively. Electrophoresis of RNA in nondenaturing gels was carried out as described in Marshall and Schneemann (29), while electrophoresis in denaturing agarose formaldehyde gels and Northern blot analysis were performed as described previously (48). The probes used for hybridization were digoxigenin-UTP labeled and complementary either to nucleotides 385 through 3107 of RNA1 or to nucleotides 124 through 1400 of RNA2. The synthesis of these probes was previously described (22), and prehybridization, hybridization, and chemiluminescent detection were carried out according to the manufacturer's protocols (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

Electrophoretic and immunoblot analyses of proteins.

Protein samples were run on NuPage 4 to 12% gels (Invitrogen) and stained with SimplyBlue SafeStain (Invitrogen). Immunoblot analysis was carried out as described previously (9).

EM.

FHV particles were negatively stained with uranyl acetate as described previously (9), and samples were viewed in a Phillips CM 100 transmission EM at 100 kV.

Confocal microscopy.

The lectin concanavalin A was previously shown to promote the attachment and spreading of S2 cells (43). These cells were therefore infected with FHV or transfected with specific RNA mixtures and grown in 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation) that had been treated with 0.5 mg/ml concanavalin A (Sigma-Aldrich) and allowed to air dry. For infected cells, suspensions of 4 × 107 cells per ml were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 as described previously (13). Aliquots of 2 × 106 cells were then diluted into 2 ml of complete growth medium and transferred to glass-bottom dishes for continued incubation at 27°C. For transfection, 2 × 106 S2 cells were allowed to attach to the dishes and were then transfected with RNA-liposome mixes, as described previously (45), with the exception that 20 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used as the transfection reagent. At appropriate time points, the cells were processed for confocal microscopy using a modified version of a previously described technique for the examination of cytoskeletal elements in S2 cells (43). Accordingly, the cells were washed in 80 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid); pH 6.8], 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM MgCl2 and fixed in the same buffer containing 0.3% glutaraldehyde (EM Sciences), 3% formaldehyde (EM Sciences), and 1 mg/ml saponin for 10 min. The cells were then permeabilized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.2% Triton X-100 and blocked for 1 h in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum (Sigma) and 0.0001% Triton X-100. All primary antibodies, as well Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 555 secondary antibodies, were applied to the fixed cells for 1 h, followed by extensive washing with PBS containing 0.0001% Triton X-100. In vivo labeling with MitoTracker and staining with DAPI and Alexa Fluor 555-phalloidin were in accordance with protocols supplied by the manufacturer. The cells were coverslipped in Immuno Fluore mounting medium (MP Biomedicals), and fluorescence and differential interference contrast images of these cells were captured using a Bio-Rad (Zeiss) Radiance 2100 Rainbow Laser Scanning confocal microscope. Image J, version 1.38T, and PhotoShop CS, version 8 (Adobe Systems Incorporated), were used to generate representations of these images. For colocalization analysis, Image J was used to flatten stacked images representing top, middle, and bottom parts of a cell and to estimate thresholds of pixel intensity for each of the resultant projections. Averaged threshold values for each cell were then used for three-dimensional colocalization analysis using the colocalization module of Imaris, version 6.1 (Bitplane). For statistical analysis, significance was reported using a Student's paired t test (Microsoft Excel X). P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

The ARM is required for specific packaging of FHV RNA1.

Arginine residues are known to confer RNA binding specificity (3, 5, 39, 60), and we therefore set out to determine whether the ARM, which spans residues 32 to 50 of FHV coat protein, confers specific packaging to viral RNA1. To this end, the arginine residues were systematically replaced with alanines in sets of three, progressing toward neutralization of all 12 residues (Fig. 1). To assess the effect of the mutations on the encapsidation of FHV RNA, capped in vitro synthesized mutant RNA2 transcripts (coat protein message) were transfected together with wt RNA1 (RdRp message) into Drosophila cells. After 24 h, when replication of the transfected RNAs had given rise to viral progeny, the cells were lysed by freezing and thawing, and released virions were used to infect fresh cells to boost particle yield. At 48 h, infected cells contained high levels of viral RNA and progeny particles, with the notable exception of mutants 5 and 6, which gave rise to significantly reduced or undetectable levels of RNA and particles, respectively (Fig. 2A). Reverse transcription-PCR and sequence analysis confirmed that all mutants for which RNA was detectable were stable and that none had reverted to wt under these experimental conditions (data not shown). The transfection/infection experiment was then repeated, and at 48 hpi, progeny particles were purified by sucrose gradient sedimentation, and packaged RNA was extracted and analyzed by gel electrophoresis.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of coat protein mutants containing modifications in the ARM spanning residues 32 to 50. The two regions shaded in gray have been shown previously to be important for packaging of either RNA2 (residues 1 to 31) or both FHV RNAs (residues 381 to 407) (29, 45). Three phenylalanine residues within the latter region have been identified as important contributors to FHV RNA recognition, presumably via base-stacking interactions with the viral RNA (45). Mutations in the FHV ARM included substitutions of alanine or lysine for arginine (mutants 1 to 7) and replacement with the ARM of the HIV-1 Rev protein (mutant 8).

FIG. 2.

Effect of mutations in ARM on RNA replication, coat protein synthesis, and virus particle yield. (A) FHV RNA and proteins were generated in Drosophila DL-1 cells following the transfection/infection protocol described. At 48 hpi, total cellular RNA was extracted, electrophoresed through an agarose gel, and stained with ethidium bromide (top panel). Virions were partially purified from the cells and run on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel, followed by Coomassie staining (middle panel). Samples representing mutant 5 and mutant 6 were also subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-FHV antiserum (bottom panel). DI-RNA2 designates an RNA2-derived DI RNA while α and β designate coat precursor protein α and cleavage product β, respectively. (B) For mutants 5 and 6, analyses of FHV RNA and coat protein synthesis were also carried out at 12 h posttransfection of Drosophila DL-1 cells. An ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel of total RNA (left panel) and immunoblot analysis of cell lysates (right panel) are shown. The α-tubulin immunoblot serves as a loading control.

Gradient profiles of mutants 1 to 4 showed that they formed particles with sedimentation rates equivalent to wt particles (data not shown). Electrophoretic analysis of the packaged RNA revealed minor variations compared to the wt (Fig. 3A). Mutants 1 and 2, in which three of the 12 arginines were changed to alanine, contained normal amounts of RNA1, somewhat reduced levels of RNA2, and other RNA species not normally observed in wt FHV particles. In a previous study, similar RNA species were detected in particles assembled from a mutant lacking N-terminal residues 2 to 31 (29). In that study we demonstrated that the two RNA species with approximate molecular sizes of 2.3 and 0.9 kb represent RNA1- and RNA2-derived DI RNAs, respectively, and that the other RNAs were also derived from FHV genomic RNA. The reason for the rapid appearance and encapsidation of these DI RNAs despite the limited number of passages is currently unknown. Interestingly, mutants 3 and 4 showed an RNA packaging phenotype more like the wt even though 6 of the 12 arginine residues were changed to alanines.

FIG. 3.

Effect of mutations in ARM on RNA packaging. RNA was extracted from gradient-purified virions assembled from the indicated mutant coat proteins and subjected to electrophoresis in nondenaturing agarose gels, followed by ethidium bromide staining (A to C and F). For mutant 6, RNA extracted from particles sedimenting in three neighboring gradient fractions (fr) is shown in panel C. (D) Electron micrograph of negatively stained purified mutant 6 particles. (E) Northern blot analysis of RNA extracted from mutant 6 particles using negative-sense RNA1 and RNA2 probes. Equivalent amounts of this RNA were loaded into each lane. DI-RNA1 and DI-RNA2 designate RNA1- and RNA2-derived DI RNAs, respectively, and arrows point to smaller RNA1- and RNA2-derived RNA species detected within the packaged RNA. RNA extracted from authentic FHV particles (wt) was included as a control.

More dramatic effects were observed when 9 or 12 arginines were changed to alanines in mutants 5 and 6, respectively. Electrophoretic analysis showed that mutant 5 particles contained significantly less RNA1 than RNA2 (Fig. 3B). For mutant 6, particles could not be obtained using the transfection/infection protocol of Drosophila cells. These results were consistent with the observation that infected cells contained no detectable viral RNA or coat protein (Fig. 2A). In contrast, cells transfected with mutant 6 RNAs showed that replication of the RNAs and coat protein synthesis were similar to wt (Fig. 2B). The transfection protocol was therefore scaled up, and mutant 6 particles were gradient purified 24 h later without subsequent amplification by infection of fresh cells. Only a minute amount of virus particles was obtained for mutant 6, and RNA extraction showed that they contained RNA2 but not RNA1 (Fig. 3C). Such particles would be noninfectious as they lack the RdRp gene, explaining why we were unable to isolate progeny virions from “infected” cells using the transfection/infection protocol. EM of mutant 6 particles indicated that they were similar in size and shape to wt particles although some particles appeared to be more stain permeable (Fig. 2D). Given that these particles sedimented at a rate similar to that of wt virions (data not shown), mutant 6 particles presumably contained multiple copies of RNA2, although this needs to be confirmed independently.

To further verify that mutant 6 particles did not contain RNA1, we performed Northern blot analysis with probes for the detection of FHV genomic RNAs. RNA1 could not be detected, while RNA2 was readily detected within the packaged RNA (Fig. 2E). This analysis additionally revealed the presence of smaller RNA1- and RNA2-derived species, which were also detected in ethidium bromide-stained gels and probably represented DI RNAs.

Several observations ruled out the possibility that the defective packaging of RNA1 by mutants 5 and 6 was due to indirect effects such as replication efficiency of the viral RNAs. For both mutants, RNA1 was easily detectable by ethidium bromide staining as early as 12 h posttransfection (Fig. 2B, left panel), indicating that it was amplified by RdRp-dependent replication. The small amounts of RNA transfected into the cells are not visible using this staining method (data not shown). Moreover, RNA1 was replicated at an efficiency comparable to that of RNA2 because roughly proportionate levels of RNAs 1 and 2 were detected in cells in which mutant 5 particles (Fig. 2A, top panel) and mutant 6 particles (Fig. 2B, left panel) were assembled.

Taken together, these results suggested that the ARM of FHV coat protein is a critical determinant for specific encapsidation of RNA1. In addition, the ARM presumably plays an important role in neutralizing and condensing FHV RNAs during assembly, explaining the low efficiency with which mutant 6 protein formed progeny virions (10, 44, 53, 54).

The positively charged nature of the ARM is required for packaging of RNA1.

To determine whether specific arginine residues in the ARM were required for packaging of RNA1 or whether it was the positively charged nature of the amino acid side chain that was important, all arginine residues in the ARM were changed to lysines in mutant 7 (Fig. 1). In addition, the FHV ARM was replaced with the ARM of the HIV-1 Rev protein in mutant 8 to determine if a particular arrangement of arginine residues was of any significance (Fig. 1). Mutant 7 and 8 RNA2s were capable of robust replication, and coat proteins translated from these RNAs assembled efficiently into virus particles (Fig. 2A). Electrophoretic analysis of the RNA contents of these particles demonstrated that they packaged both genomic RNAs (Fig. 3F). The packaging phenotype of mutant 7 was identical to that of the wt while small amounts of atypical RNA species were detected for mutant 8, similar to what was observed for mutants 3 and 4. These results suggested that the positively charged nature of the ARM was the sole feature underlying its role in specific recognition of RNA1.

Subcellular localization of FHV coat protein.

It was unclear how the positively charged nature of the ARM could confer specific packaging of RNA1, given that the presumed association with the RNA substrate appeared to be based solely on electrostatic interactions. We therefore hypothesized that the ARM might specify alternate or additional functions such as locating the coat protein to a cellular site important for retrieval of RNA1 during assembly. Because the location of the wt coat protein in FHV-infected cells had not yet been reported, we initially focused our attention on visualizing the wt coat protein and RdRp in Drosophila cells at early, intermediate, and late times after infection using confocal immunomicroscopy. From previous studies it was already known that RdRp is located on the outer membrane of mitochondria, where it forms spherules that serve as the sites for RNA replication (20, 31).

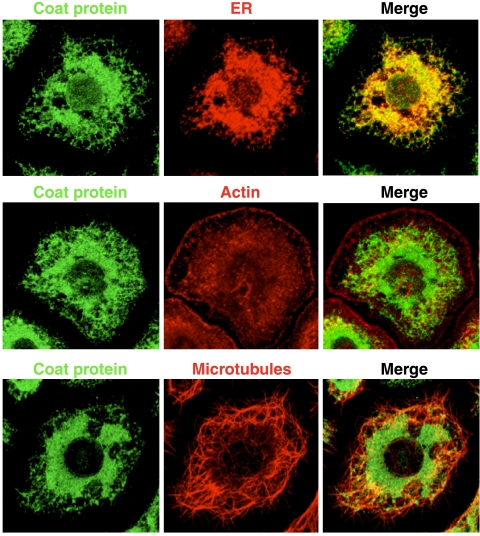

At 6 and 9 hpi, the coat protein showed a distinct subcellular distribution that was reminiscent of a reticulo-endothelial pattern (Fig. 4A and E). Indeed, counterstaining with an antibody specific to ER-resident proteins containing KDEL motifs showed that coat protein signal closely followed the ER network while there was no resemblance to cytoskeletal networks visualized for actin or microtubules (Fig. 5). In contrast, association between FHV RdRp and the ER was not observed at any of the time points investigated. Instead, this protein appeared to localize exclusively to mitochondria, as evidenced by MitoTracker fluorescence (Fig. 6A). FHV RdRp initially exhibited a punctate distribution dispersed throughout the cytoplasm but showed significant perinuclear clustering as early as 9 hpi (Fig. 4B and F and 6B). This clustering further intensified as infection progressed (Fig. 4J). Perinuclear aggregation of mitochondria, which usually exhibit uniform cytosolic distribution, is a hallmark of nodavirus infection that has also been observed in vivo (14).

FIG. 4.

Subcellular distribution of coat protein and RdRp during the course of infection. Drosophila S2 cells were infected with FHV at an MOI of 5 and processed for immunofluorescence staining at 6, 9, and 15 hpi as described in Materials and Methods. Polyclonal rabbit anti-FHV and monoclonal mouse anti-FHV RdRp antibodies were used to stain coat protein and RdRp, respectively, and DAPI was used as a nuclear stain. Z-series projections of several optical sections are shown. A more powerful laser setting was required to detect coat protein at 6 hpi (A) than at 9 and 15 hpi (E and I) because this protein was present at low intracellular levels during the initial stages of infection. Yellow pixels represent subcellular areas where coat protein and RdRp colocalize (D, H, and L), and arrows point to coat protein aggregates visualized at late stages of infection (I).

FIG. 5.

Comparison between distribution patterns of coat protein and ER, actin, and microtubule networks. Drosophila S2 cells were infected with FHV at an MOI of 5, and at 9 hpi the cells were fixed, permeabilized, stained with polyclonal anti-FHV for the detection of coat protein, and counterstained with either monoclonal anti-KDEL (ER marker), Alexa Fluor 555-phalloidin (actin marker), or monoclonal anti-α-tubulin (microtubule marker). Z-series projections of several optical sections are shown. Yellow pixels in merged images are indicative of colocalization between green and red fluorescence signals.

FIG. 6.

Redistribution of mitochondria and ER in FHV-infected Drosophila S2 cells. (A) Confocal immunofluorescence image of perinuclear area of infected cell labeled for detection of mitochondria (MitoTracker Red) and RdRp (monoclonal anti-FHV RdRp). The green-magenta color combination utilized for this pseudo-colored image illustrates that fluorescence signals for RdRp form rings around those for MitoTracker (indicated by white arrows). Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) Comparison between patterns of mitochondrial distribution in uninfected and infected cells. Mitochondria were detected using MitoTracker Red, and cellular limits (white lines) were determined by differential interference contrast microscopy. (C) Comparison between ER distribution patterns in uninfected cells and infected cells at 9 and 15 hpi. The ER was detected using monoclonal anti-KDEL antibodies. A single optical section is shown in panel A while Z-series projections of several optical sections are shown in panels B and C.

A closer examination of the fluorescence signal for RdRp showed that it surrounded the signal for the mitochondrial matrix-specific stain MitoTracker (Fig. 6A), in agreement with previous reports that RdRp is located in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Merging the fluorescence signals for coat protein and RdRp at 6 and 9 hpi revealed that a considerable fraction of coat protein was detected in close proximity to the RdRp, indicating that coat protein was located not only near the ER but also in the vicinity of RNA replication sites (Fig. 4D and H).

At 15 hpi, a substantial amount of coat protein remained proximal to the RdRp (Fig. 4L) and ER (data not shown), but many cells showed coat protein in sizeable aggregates within the cytoplasm (Fig. 4I). These aggregates most probably represented progeny virus particles that are known to form large paracrystalline arrays at late stages of infection (14, 26, 33). Note that the coat protein antibody used in these experiments does not distinguish between unassembled and assembled protein subunits.

While the perinuclear clustering of mitochondria in nodavirus-infected cells has been reported previously, we observed that the ER also underwent a significant retraction toward the perinuclear region during the course of infection (Fig. 6C). This retraction mirrored the progressive accumulation of coat protein in perinuclear regions near the RdRp, suggesting that these two events might be closely coordinated.

RNA1 packaging-deficient mutant exhibits significant reduction in colocalization with RdRp.

We next determined if the subcellular distribution pattern of RNA1 packaging-deficient mutant 6 deviated from that of the wt coat protein. Two previously described RNA packaging mutants called Δ31 and Δγ381 were included in this analysis. In Δ31, N-terminal residues 2 to 31 are deleted, rendering this mutant unable to efficiently package RNA2 (29), while the absence of the C-terminal 26 residues of the coat protein in Δγ381 results in an inability to efficiently package either of the two genomic RNAs (45). To investigate the subcellular localization of the packaging-deficient mutants, Drosophila cells were cotransfected with wt RNA1 and mutated capped RNA2 transcripts and processed for immunofluorescence analysis at 12 h posttransfection. At this time point, the transfected cells exhibited a degree of coat protein accumulation similar to that observed in infected cells at 9 hpi (data not shown). While the subcellular distribution patterns of Δ31 and Δγ381 were indistinguishable from the wt, mutant 6 exhibited a dramatic reduction in the amount of coat protein colocalizing with RdRp at mitochondrial replication complexes (Fig. 7A). Quantitative analysis of pixel colocalization demonstrated that 30% ± 8% of red pixels (RdRp) were associated with green pixels (coat protein) for mutant 6 compared to 85% ± 7% for the wt (Fig. 7B). This analysis furthermore showed that Δ31 and Δγ381 did not exhibit significant reductions in RdRp colocalization. Results from this study therefore suggested a specific role for the ARM in spatially coordinating FHV coat protein with RNA replication complexes. Mutants 7 and 8 were also analyzed to determine if the sequence of the ARM or the identity of positively charged residues in the ARM were important to localize coat proteins to the site of RNA replication. Results from colocalization analyses suggested that this was not the case because RdRp colocalized with both mutants to a similar extent as the wt coat protein (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Subcellular localization of coat protein mutants. Drosophila S2 cells were cotransfected with wt RNA1 and in vitro RNA transcripts encoding wt and mutated versions of coat protein, which included RNA packaging-deficient mutants Δ31, mutant 6, and Δγ381, as well as mutants 7 and 8. At 12 h posttransfection, the cells were stained with rabbit anti-FHV for the detection of coat protein and monoclonal mouse anti-FHV RdRp. (A) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images for wt, Δ31, mutant 6, and Δγ381. Z-series projections of several optical sections are shown. Subcellular regions of immunofluorescence colocalization are yellow. (B) Graphic representation of the percentage of red pixels (RdRp) colocalizing with green pixels (coat protein) for wt and mutant coat proteins. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean of at least five independently analyzed cells. *, P = 0.005 compared to the wt.

ARM represents sole determinant for localizing coat proteins to RdRp.

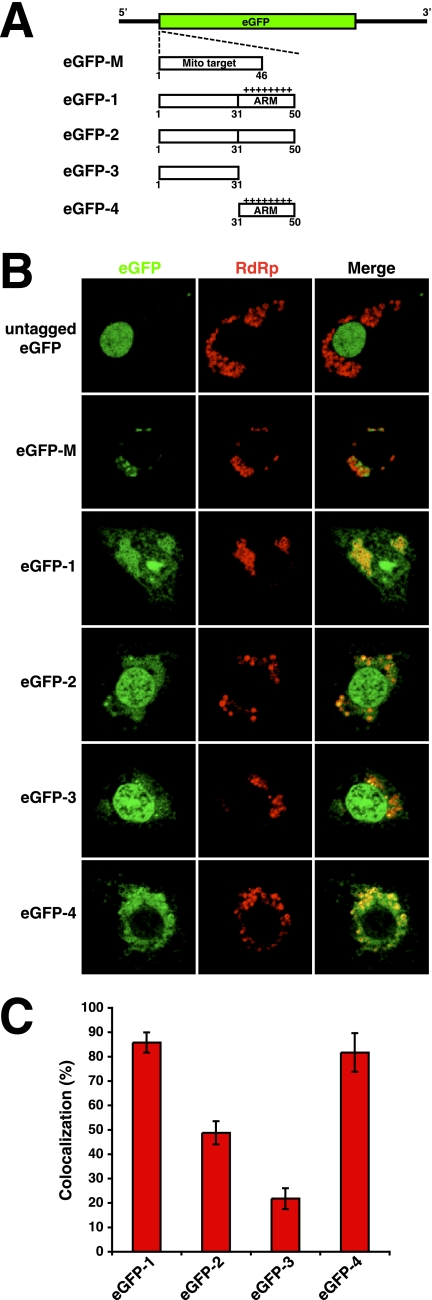

To determine if the ARM was sufficient for the targeting of proteins to RNA replication complexes, gain-of-function analyses were carried out with eGFP fusion proteins containing tags derived from the N terminus of the coat protein. Coding sequences for these proteins were inserted into a DI RNA derived from RNA2 (61). This allowed the translation of the fusion proteins from replicons amplified by FHV RdRp in Drosophila cells. Figure 8A schematically illustrates the fusion proteins used for this analysis. No colocalization between untagged eGFP and RdRp was apparent in transfected cells (Fig. 8B). Instead, eGFP predominately partitioned to nuclei, as is frequently observed (50). Conversely, the eGFP fusion protein eGFP-M, which contained the mitochondrion-targeting signal of FHV RdRp and served as a positive control, was exclusively detected proximal to RdRp, where overlapping fluorescent patterns for eGFP and RdRp were observed (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Subcellular localization eGFP fusion proteins containing tags derived from the N terminus of coat protein. (A) Schematic representation of eGFP fusion constructs. The eGFP reading frame (green) in the DI RNA used for the generation of these constructs is indicated. “Mito target” in mutant eGFP-M designates the mitochondrion-targeting signal of FHV RdRp. (B) Representative confocal fluorescence images for eGFP fusion studies. Drosophila S2 cells were cotransfected with wt RNA1- and RNA2-derived DI RNAs encoding eGFP or N-terminally tagged versions of this protein. At 12 h posttransfection, the cells were stained with monoclonal mouse anti-FHV RdRp for the detection of RdRp at mitochondria. The images represent single optical sections. Subcellular regions of fluorescence colocalization are yellow. (C) Graphic representation of the percentage of red pixels (RdRp) colocalizing with green pixels (eGFP) for eGFP proteins containing tags derived from the N terminus of the coat protein. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean of at least seven independently analyzed cells.

Interestingly, colocalization between eGFP and RdRp was observed for a fusion protein designated eGFP-1, which contained the N-terminal 50 residues of FHV coat protein (Fig. 8B). A high percentage of RdRp colocalization was measured for this fusion protein, equivalent to what was obtained for wt coat protein (compare Fig. 7B and 8C). Mutant eGFP-1 furthermore displayed reticular patterns that were similar to those observed for the wt protein (Fig. 8B). However, unlike the wt coat protein, this fusion protein showed some degree of nuclear localization. Mutations in the N-terminal coat protein tag of eGFP-1 demonstrated that the ARM within this tag enabled colocalization between eGFP-1 and RdRp. Specifically, replacement of all 12 arginine residues within the ARM with alanine residues decreased RdRp colocalization from 86% ± 4% to 49% ± 5% (Fig. 8B and C, eGFP-2), while deletion of residues 32 to 50 encompassing the ARM resulted in an additional reduction to 22% ± 4% (Fig. 8B and C, eGFP-3). Conversely, no significant decrease in RdRp colocalization was obtained upon deletion of N-terminal residues 2 to 31 preceding the ARM (Fig. 8B and C, eGFP-4). Fusion proteins eGFP-1 and eGFP-4 furthermore exhibited decreased distribution to nuclei, compared to eGFP-2 and eGFP-3, suggesting that the ARM-mediated targeting of these proteins to mitochondria increased their retention within the cytosol (Fig. 8B).

DISCUSSION

This study was initiated to investigate whether an arginine-rich motif in the N terminus of the FHV coat protein plays a role in specific packaging of RNA1. Our previous results had indicated that the two nodaviral genome segments are independently recognized during assembly and that different regions of the coat protein are involved in this process. Our focus on the ARM as a candidate for representing a determinant for packaging of RNA1 was based on several considerations. First, this region is located in close proximity to packaged RNA in fully assembled particles, and it had also been shown to be strictly required for the assembly of virions (9, 10, 45). Second, ARMs play a central role in RNA recognition based on the ability of the arginine side chain to establish a wide variety of specific molecular contacts that can be mimicked only inefficiently by other amino acids including lysine (58). We found that replacement of the 12 arginines in the ARM with alanine indeed inhibited packaging of RNA1 but that packaging of this segment was unaffected when the arginines were replaced with lysines. In addition, we showed that RNA1 recognition is independent of the sequence of the ARM because the replacement of this motif with the ARM of the HIV-1 Rev protein did not significantly affect RNA1 packaging. These results suggested that the ARM is not involved in recognition of a specific motif on RNA1 but, rather, that a high density of positive charge is required for the encapsidation of this genomic segment. Positive charge alone, however, cannot confer specific binding to a given RNA, and we therefore suspected that the results reflected functions of the ARM autonomous of its presumed interaction with RNA.

Specific packaging of FHV RNAs not only depends on physical interactions between coat protein subunits and viral genomic segments but also requires coat protein synthesis from replicating RNA2 (57). We recently demonstrated that coat protein translated from a nonreplicating mRNA does not participate in packaging of the viral genome, leading us to propose that viral RNA replication, translation, and specific packaging are processes that are spatially linked and occur in special cellular compartments akin to viral factories or viroplasms. More specifically, we had postulated that coat protein synthesis occurs proximal to mitochondrial sites of RNA replication and that this permits immediate access to RNA1 and RNA2 for genome incorporation (57). Given that the cellular location of coat protein was unknown at the start of the current study, we chose to investigate this aspect in infected Drosophila cells to provide an experimental basis for this hypothesis and to determine whether the ARM played any role in determining the cellular location of coat protein.

In keeping with our model, significant amounts of wt coat protein were detected in subcellular regions occupied by the RNA replication complexes. Surprisingly, a considerable fraction of the protein also distributed to sites where its patterning matched that of the ER. This was observed for wt and mutant proteins at all time points and was independent of their ability to colocalize with RNA replication complexes as, for example, in the case of mutant 6. The two locations must therefore be specified by different signals, and the protein likely originates at the ER. This raised the question of whether the ER serves as the site of coat protein synthesis. Since coat protein is not a membrane protein and is not known to enter the secretory pathway, translation would have to occur in a manner independent of the signal recognition particle pathway. Recent reports have shown that mRNA partitioning between the cytosol and ER may involve additional mechanisms that do not involve the signal recognition particle pathway (35, 40), raising the intriguing possibility that FHV RNA2 may be directed to ER-associated ribosomes for translation. Confirmation of this hypothesis will have to await further analysis.

Our microscopy studies of the various coat protein mutants showed that the Rev ARM effectively compensated for the FHV ARM in localizing mutant 8 to RNA replication sites at mitochondria. In the HIV-1 Rev protein, the Rev ARM constitutes part of a nuclear localization signal (4, 6, 24, 56). Clearly, this function could be overridden by extraneous sequences derived from the FHV coat protein, presumably because the Rev ARM does not function autonomously in nuclear localization. (17, 28, 51, 52).

Microscopic analysis of mutant 6, in which all arginine residues in the ARM had been changed to alanines, showed that this RNA1 packaging-deficient mutant was defective in its ability to colocalize with the replication complexes. Gain-of-function studies confirmed that this was due to the removal of the arginine residues because a reduction in colocalization with the replication complexes was also observed for the corresponding eGFP fusion protein. GFP fusion protein studies additionally demonstrated that the ARM by itself was sufficient to localize coat proteins to the FHV RdRp at mitochondria. The possibility that the coat proteins and eGFP fusion proteins that were detected in close association with the replication site physically associated with mitochondria by interaction with the outer membrane is unlikely because the ARM does not match any of the common outer mitochondrial targeting signals, which often consist of transmembrane domains with flanking positively charged residues (15).

Our data indicate that localization of coat protein at the site of viral RNA replication requires the ARM and that the inability to localize to this site coincides with failure to package RNA1. A model describing encapsidation of the bipartite FHV genome consistent with these data would necessarily propose that packaging of RNA1 and RNA2 takes place in different cellular microenvironments. Furthermore, it would have to postulate that packaging of the two RNAs occurs sequentially, presumably in the order of RNA2 before RNA1. RNA2 serves as the template for translation of the coat protein, possibly on or in close apposition to the ER. RNA1 translation, on the other hand, sharply declines at 6 hpi, but its synthesis continues at a high rate throughout infection (11, 13). Newly synthesized RNA1 may thus accumulate around mitochondria, whereas RNA2 is transported to sites of translation for generation of the large amounts of coat protein typically observed during FHV infection. The role of RNA2 as the coat protein message raises the possibility that recognition of this RNA occurs in a cotranslational manner at the site of translation. A complex of coat protein subunits and RNA2 may then traffic to the mitochondria for retrieval of RNA1. The ARM could represent a motif that actively directs coat protein to this location. Alternatively, the coat protein may be transported to this site passively by retraction of the ER to the perinuclear site where mitochondria accumulate. In this case, perinuclear clustering of mitochondria and the ER would play an active role in the FHV life cycle rather than being a mere bystander effect of the infection. The role of the ARM in the latter scenario may serve to tether the coat protein loosely to the ER membrane by virtue of electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged head groups of the phospholipids. Clearly, much of this model is still speculative, and further experimentation is required to confirm the details. However, the model integrates our previous observations that coat protein translation from replicating RNA and specific genome recognition are linked. In our earlier analysis, this linkage was not attributed to a cotranslational packaging mechanism because coat proteins were shown to package mutant RNA2 transcripts with closed coat protein reading frames. However, an alternate explanation for this result is that the mutant RNA2 was packaged in preference to RNA1, subsequent to the cis-packaging of wt RNA2. Additional experiments are required to distinguish between these possibilities.

There is growing evidence that the genomes of multipartite RNA viruses are packaged by different mechanisms, each presumably providing an advantage to the specific type of virus. For bacteriophage φ6, a model has been proposed whereby multiple genome segments are packaged into preformed capsids in a sequential manner (32). In this model, the interaction of one segment to a binding site on the capsid protein induces a conformational change that allows for the packaging of another. For other viruses, genome packaging appears to be dependent on specific interactions between individual viral RNA strands prior to encapsidation. Such a mode of packaging has been implicated in the functional linkage between HIV-1 genome dimerization and encapsidation (27, 42) and has also been proposed to be involved in the copackaging of red clover necrotic mosaic virus RNA-1 and RNA-2 (2). Here, we propose a third model for multipartite genome packaging, in which viral genome strands are recognized sequentially and in distinct cellular microenvironments. This model serves as a basis for future studies to unravel the molecular details underlying nodaviral genome packaging.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM53491).

We thank Malcolm R. Wood and William B. Kiosses from the Core Microscopy Facility at The Scripps Research Institute for support with microscopic analyses. We are also grateful to Paul Ahlquist (Institute for Molecular Virology, University of Wisconsin-Madison) for providing antibodies to FHV RdRp and to Ranjit Dasgupta (Department of Animal Health and Biomedical Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison) for providing plasmid pDIeGFP.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 January 2009.

Manuscript 19728 from The Scripps Research Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball, L. A., and K. L. Johnson. 1998. Nodaviruses of insects, p. 225-267. In L. K. Miller and L. A. Ball (ed.), The insect viruses. Plenum, New York, NY.

- 2.Basnayake, V. R., T. L. Sit, and S. A. Lommel. 2006. The genomic RNA packaging scheme of Red clover necrotic mosaic virus. Virology 345532-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battiste, J. L., H. Mao, N. S. Rao, R. Tan, D. R. Muhandiram, L. E. Kay, A. D. Frankel, and J. R. Williamson. 1996. Alpha helix-RNA major groove recognition in an HIV-1 Rev peptide-RRE RNA complex. Science 2731547-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohnlein, E., J. Berger, and J. Hauber. 1991. Functional mapping of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev RNA binding domain: new insights into the domain structure of Rev and Rex. J. Virol. 657051-7055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai, Z., A. Gorin, R. Frederick, X. Ye, W. Hu, A. Majumdar, A. Kettani, and D. J. Patel. 1998. Solution structure of P22 transcriptional antitermination N peptide-box B RNA complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cochrane, A. W., A. Perkins, and C. A. Rosen. 1990. Identification of sequences important in the nucleolar localization of human immunodeficiency virus Rev: relevance of nucleolar localization to function. J. Virol. 64881-885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dasgupta, R., L. L. Cheng, L. C. Bartholomay, and B. M. Christensen. 2003. Flock house virus replicates and expresses green fluorescent protein in mosquitoes. J. Gen. Virol. 841789-1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dearing, S. C., P. D. Scotti, P. J. Wigley, and S. D. Dhana. 1980. A small RNA virus isolated from the grass grub, Costelytra zealandica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). N.Z. J. Zool. 7267. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong, X. F., P. Natarajan, M. Tihova, J. E. Johnson, and A. Schneemann. 1998. Particle polymorphism caused by deletion of a peptide molecular switch in a quasiequivalent icosahedral virus. J. Virol. 726024-6033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher, A. J., and J. E. Johnson. 1993. Ordered duplex RNA controls capsid architecture in an icosahedral animal virus. Nature 361176-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friesen, P. D., and R. R. Rueckert. 1984. Early and late functions in a bipartite RNA virus: evidence for translational control by competition between viral mRNAs. J. Virol. 49116-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friesen, P. D., and R. R. Rueckert. 1981. Synthesis of Black beetle virus proteins in cultured Drosophila cells: differential expression of RNAs 1 and 2. J. Virol. 37876-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallagher, T. M., and R. R. Rueckert. 1988. Assembly-dependent maturation cleavage in provirions of a small icosahedral insect ribovirus. J. Virol. 623399-3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garzon, S., H. Strykowski, and G. Charpentier. 1990. Implication of mitochondria in the replication of Nodamura virus in larvae of the Lepidoptera, Galleria mellonella (L.) and in suckling mice. Arch. Virol. 113165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habib, S. J., W. Neupert, and D. Rapaport. 2007. Analysis and prediction of mitochondrial targeting signals. Methods Cell Biol. 80761-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoogenraad, N. J., L. A. Ward, and M. T. Ryan. 2002. Import and assembly of proteins into mitochondria of mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 159297-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hope, T. J., D. McDonald, X. J. Huang, J. Low, and T. G. Parslow. 1990. Mutational analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev transactivator: essential residues near the amino terminus. J. Virol. 645360-5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horton, R. M., S. N. Ho, J. K. Pullen, H. D. Hunt, Z. Cai, and L. R. Pease. 1993. Gene splicing by overlap extension. Methods Enzymol. 217270-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanaji, S., J. Iwahashi, Y. Kida, M. Sakaguchi, and K. Mihara. 2000. Characterization of the signal that directs Tom20 to the mitochondrial outer membrane. J. Cell Biol. 151277-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopek, B. G., G. Perkins, D. J. Miller, M. H. Ellisman, and P. Ahlquist. 2007. Three-dimensional analysis of a viral RNA replication complex reveals a virus-induced mini-organelle. PLoS Biol. 5e220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramvis, A., and M. C. Kew. 1998. Structure and function of the encapsidation signal of Hepadnaviridae. J. Viral Hepat. 5357-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishna, N. K., D. Marshall, and A. Schneemann. 2003. Analysis of RNA packaging in wild-type and mosaic protein capsids of flock house virus using recombinant baculovirus vectors. Virology 30510-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishna, N. K., and A. Schneemann. 1999. Formation of an RNA heterodimer upon heating of nodavirus particles. J. Virol. 731699-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubota, S., H. Siomi, T. Satoh, S. Endo, M. Maki, and M. Hatanaka. 1989. Functional similarity of HIV-I rev and HTLV-I rex proteins: identification of a new nucleolar-targeting signal in rev protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 162963-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuroda, R., T. Ikenoue, M. Honsho, S. Tsujimoto, J. Y. Mitoma, and A. Ito. 1998. Charged amino acids at the carboxyl-terminal portions determine the intracellular locations of two isoforms of cytochrome b5. J. Biol. Chem. 27331097-31102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanman, J., J. Crum, T. J. Deerinck, G. M. Gaietta, A. Schneemann, G. E. Sosinsky, M. H. Ellisman, and J. E. Johnson. 2008. Visualizing flock house virus infection in Drosophila cells with correlated fluorescence and electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 161439-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lever, A. M. 2007. HIV-1 RNA packaging. Adv. Pharmacol. 551-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malim, M. H., S. Bohnlein, J. Hauber, and B. R. Cullen. 1989. Functional dissection of the HIV-1 Rev trans-activator—derivation of a trans-dominant repressor of Rev function. Cell 58205-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall, D., and A. Schneemann. 2001. Specific packaging of nodaviral RNA2 requires the N-terminus of the capsid protein. Virology 285165-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, D. J., and P. Ahlquist. 2002. Flock house virus RNA polymerase is a transmembrane protein with amino-terminal sequences sufficient for mitochondrial localization and membrane insertion. J. Virol. 769856-9867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller, D. J., M. D. Schwartz, and P. Ahlquist. 2001. Flock house virus RNA replicates on outer mitochondrial membranes in Drosophila cells. J. Virol. 7511664-11676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mindich, L. 1999. Precise packaging of the three genomic segments of the double-stranded-RNA bacteriophage φ6. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63149-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy, F. A., W. F. Scherer, A. K. Harrison, H. W. Dunne, and G. W. Gary, Jr. 1970. Characterization of Nodamura virus, an arthropod transmissible picornavirus. Virology 401008-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Netherton, C., K. Moffat, E. Brooks, and T. Wileman. 2007. A guide to viral inclusions, membrane rearrangements, factories, and viroplasm produced during virus replication. Adv. Virus Res. 70101-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicchitta, C. V., R. S. Lerner, S. B. Stephens, R. D. Dodd, and B. Pyhtila. 2005. Pathways for compartmentalizing protein synthesis in eukaryotic cells: the template-partitioning model. Biochem. Cell Biol. 83687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owen, K. E., and R. J. Kuhn. 1996. Identification of a region in the Sindbis virus nucleocapsid protein that is involved in specificity of RNA encapsidation. J. Virol. 702757-2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palese, P. 1977. The genes of influenza virus. Cell 101-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patton, J. T., and E. Spencer. 2000. Genome replication and packaging of segmented double-stranded RNA viruses. Virology 277217-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puglisi, J. D., L. Chen, S. Blanchard, and A. D. Frankel. 1995. Solution structure of a bovine immunodeficiency virus Tat-TAR peptide-RNA complex. Science 2701200-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pyhtila, B., T. Zheng, P. J. Lager, J. D. Keene, M. C. Reedy, and C. V. Nicchitta. 2008. Signal sequence- and translation-independent mRNA localization to the endoplasmic reticulum. RNA 14445-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qu, F., and T. J. Morris. 1997. Encapsidation of turnip crinkle virus is defined by a specific packaging signal and RNA size. J. Virol. 711428-1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rein, A. 1994. Retroviral RNA packaging: a review. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 9513-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers, S. L., G. C. Rogers, D. J. Sharp, and R. D. Vale. 2002. Drosophila EB1 is important for proper assembly, dynamics, and positioning of the mitotic spindle. J. Cell Biol. 158873-884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneemann, A. 2006. The structural and functional role of RNA in icosahedral virus assembly. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 6051-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneemann, A., and D. Marshall. 1998. Specific encapsidation of nodavirus RNAs is mediated through the C terminus of capsid precursor protein alpha. J. Virol. 728738-8746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneemann, A., V. Reddy, and J. E. Johnson. 1998. The structure and function of nodavirus particles: a paradigm for understanding chemical biology. Adv. Virus Res. 50381-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schneemann, A., W. Zhong, T. M. Gallagher, and R. R. Rueckert. 1992. Maturation cleavage required for infectivity of a nodavirus. J. Virol. 666728-6734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider, P. A., A. Schneemann, and W. I. Lipkin. 1994. RNA splicing in Borna disease virus, a nonsegmented, negative-strand RNA virus. J. Virol. 685007-5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scotti, P. D., S. Dearing, and D. W. Mossop. 1983. Flock House virus: a nodavirus isolated from Costelytra zealandica (White) (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Arch. Virol. 75181-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seibel, N. M., J. Eljouni, M. M. Nalaskowski, and W. Hampe. 2007. Nuclear localization of enhanced green fluorescent protein homomultimers. Anal. Biochem. 36895-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stauber, R. H., E. Afonina, S. Gulnik, J. Erickson, and G. N. Pavlakis. 1998. Analysis of intracellular trafficking and interactions of cytoplasmic HIV-1 Rev mutants in living cells. Virology 25138-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szilvay, A. M., K. A. Brokstad, S. O. Boe, G. Haukenes, and K. H. Kalland. 1997. Oligomerization of HIV-1 Rev. mutants in the cytoplasm and during nuclear import. Virology 23573-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang, L., K. N. Johnson, L. A. Ball, T. Lin, M. Yeager, and J. E. Johnson. 2001. The structure of pariacoto virus reveals a dodecahedral cage of duplex RNA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 877-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tihova, M., K. A. Dryden, T. V. Le, S. C. Harvey, J. E. Johnson, M. Yeager, and A. Schneemann. 2004. Nodavirus coat protein imposes dodecahedral RNA structure independent of nucleotide sequence and length. J. Virol. 782897-2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Truscott, K. N., K. Brandner, and N. Pfanner. 2003. Mechanisms of protein import into mitochondria. Curr. Biol. 13R326-R337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Venkatesh, L. K., S. Mohammed, and G. Chinnadurai. 1990. Functional domains of the HIV-1 rev gene required for trans-regulation and subcellular localization. Virology 17639-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venter, P. A., N. K. Krishna, and A. Schneemann. 2005. Capsid protein synthesis from replicating RNA directs specific packaging of the genome of a multipartite, positive-strand RNA virus. J. Virol. 796239-6248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weiss, M. A., and N. Narayana. 1998. RNA recognition by arginine-rich peptide motifs. Biopolymers 48167-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wileman, T. 2007. Aggresomes and pericentriolar sites of virus assembly: cellular defense or viral design? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61149-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ye, X., R. A. Kumar, and D. J. Patel. 1995. Molecular recognition in the bovine immunodeficiency virus Tat peptide-TAR RNA complex. Chem. Biol. 2827-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhong, W., R. Dasgupta, and R. Rueckert. 1992. Evidence that the packaging signal for nodaviral RNA2 is a bulged stem-loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 8911146-11150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]