Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are major health burdens worldwide, with over 300 and 170 million people, respectively, infected. HBV, a DNA virus, and HCV, an RNA virus, are both hepatotropic, and both lead to hepatitis in many patients, with potentially fatal complications, including hepatocellular carcinoma. A high proportion of HCV- and HBV-infected patients develop chronic infections characterized by absent, weak, or narrowly focused T-cell responses (70). It is likely that early immune avoidance mechanisms contribute to the disturbed T-cell responses in combination with various other strategies reviewed elsewhere (7, 28, 31, 36, 70, 82). The two viruses differ considerably in their interactions with the host immune system, but all current treatment protocols aimed at clearing either virus include alpha interferon (IFN-α). This implies that the innate immune system is of pivotal importance in the development and maintenance of chronic infection versus viral clearance.

Critical components of the innate immune response are liver macrophages. Here we highlight their key roles in both the favorable and adverse responses to HBV and HCV infections.

MACROPHAGES IN THE LIVER

Macrophages are phagocytic mononuclear cells of the innate immune response which also prepare and maintain adaptive responses. Monocytes in peripheral blood differentiate into macrophages after migrating into tissues, where gene expression changes are driven by the extracellular matrix, chemokine milieu, and T cells (13, 47, 56). Kupffer cells (KCs), resident liver macrophages, are long lived and abundant, representing 15 to 20% of the total liver cell population (42, 68). Resting KCs, one of the first types of immune cells to be exposed to materials absorbed in the gut, contribute to the generally tolerogenic environment in the liver (3, 41, 68, 77, 86), including suppression of T-cell activation (51). Nevertheless, during immune responses, KCs, like circulating monocytes drawn into the liver, can be activated by various stimuli (17, 19, 22, 26, 34, 47, 57, 59, 64, 73, 77, 83) (Table 1). Low shear stress, fenestrations of sinusoidal cells, and a large contact area between blood and parenchymal cells facilitate extravasation and recruitment of immune cells to the liver (12, 43).

TABLE 1.

Macrophages activation patterns in viral infectiona

| Activation | Stimulus(i) | Upregulated surface protein(s) | Downregulated surface protein | Intracellular response | Secretory response | Functional effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | TLR engagement and additional costimulation by IFN-γ may be needed for some responses | MHC-II, CD86 | Upregulation of IRFs, iNOS, NO, and ROS | Production of inflammatory cytokines IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-12, and IL-6 and chemokines IL-8, CCL2 CCL3, and CXCL10 | Enhanced AG presentation; type 1 effector responseb | 47,59 | |

| Alternative | Type 2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 | Mannose receptor MHC-II | CD14 | Downregulation of iNOS and NO | Upregulation of IL-1Ra, IL-10, and CCL18; downregulation of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-12 | Decreased AG presentation, decreased killing of intracellular organisms, increased AG endocytosis, T-cell proliferation, and increased extracellular matrix productionc | 17, 22, 26, 34, 59, 73, 83 |

| IL-10 | IL-10/IL-10 receptor | Mannose receptor PRRs (FMLP, TLRs, and MARCO); cytokine receptors (IL-12Rβ, IL-10R, IL-2Rα, and IL-21R) | Upregulation of IL-1Ra; downregulation of cytokine and chemokine production, MHC-II, CD80, CD86, and NO | Profound inhibition of AG-presenting and effector functions; remodeling of extracellular matrix | 26, 38, 47, 57, 64 |

Abbreviations: FMLP, formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine; MARCO, macrophage receptor with collagenous structure; IRF, IFN regulatory factor; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; AG, antigen.

Enhanced killing of intracellular pathogens and proinflammatory activation of adaptive immune response (e.g., induction of IFN-γ).

Regulatory and recovery function and immunosuppression.

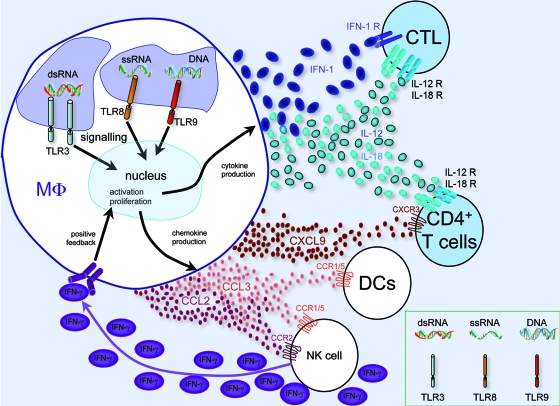

Macrophages display heterogeneous phenotypes with distinct functional capacities that vary according to tissue microenvironment and external stimuli. They monitor their environment and mediate phagocytosis via a plethora of plasma membrane receptors (90). Pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (26, 90), recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns and subsequently mediate both phagocytosis and signaling, leading to an altered macrophage phenotype (17, 22, 26, 34, 59, 64, 73, 83) (Fig. 1). Typically, innate immune activation is particle induced, antigen nonspecific, and T-cell independent (26, 47), resulting in macrophages that secrete reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide, type I IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β), and other cytokines and chemokines. Additionally, innately activated macrophages often upregulate expression of adaptive response genes, such as the gene encoding antigen presentation major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecules (42), and promote activation of primed T cells (26). In contrast, adaptive macrophage activation is modulated by direct interaction with T cells. Classical adaptive activation occurs in the presence of IFN-γ and results in macrophages with enhanced cytotoxic activity (19), whereas alternative adaptive activation, which is promoted by the type 2 cytokines interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13, results in macrophages with activities optimized for combating parasitic and extracellular pathogens (26, 55). Other activation phenotypes, including that for IL-10-mediated activation, have been described (Table 1), but IL-10 has also been associated with deactivation of macrophages, which is necessary to limit the duration and intensity of the immune responses that downregulate MHC-II and the expression of other cytokines (26, 47).

FIG. 1.

Macrophages in viral infection. Phagocytosed viral DNA and/or RNA is recognized by the endosomal TLRs TLR3 (dsRNA), TLR8 (single-stranded RNA [ssRNA]), and TLR9 (DNA), which lead to signaling, transcriptional changes, and macrophage activation and proliferation, as well as to antigen presentation (not shown). As a result, cytokines (IFN-1, IL-12, and IL-18) and chemokines (CCL2, CCL3, and CXCL9) are produced, recruiting further immune cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems (NK cells, DCs, and T cells). Positive feedback via NK cell-produced IFN-γ (purple ovals) leads to further macrophage activation. The macrophage-produced cytokines type I IFN (IFN-α and IFN-β), IL-12, and IL-18 stimulate a type 1 immune response in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Recruited DCs present viral antigens, including activated CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, to T cells, destroying infected cells (not shown). MΦ, macrophage.

MACROPHAGE INVOLVEMENT IN IMMUNE RECOGNITION OF HCV AND HBV INFECTIONS

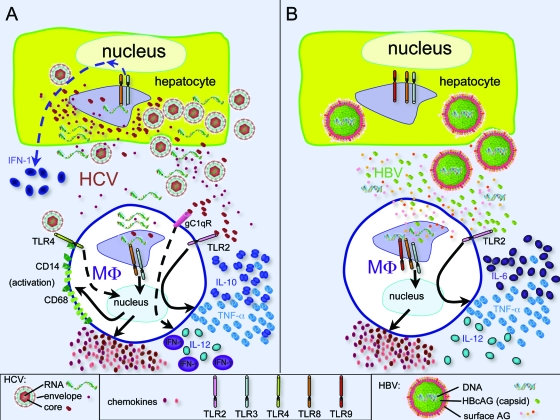

In the case of HBV infection, viral replication inside infected hepatocytes occurs within capsids, with the viral genome hidden from pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), preventing the initial HBV infection from being detected by the innate immune system (95) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the HCV life cycle is cytoplasmic in replication complexes. Although these membranous webs may shield the virus somewhat from PRRs, ubiquitously expressed cytoplasmic PRRs that detect nucleic acids, such as RIG-1 and MDA-5, likely recognize HCV and trigger secretion of detectable amounts of type I IFNs by hepatocytes (84, 85). Indeed, in studies with chimpanzees, no hepatic transcription changes are detected during the first weeks of HBV infection, whereas many hepatic transcription changes relating to the type I IFN response are seen upon HCV infection (70). There is debate as to whether macrophages, in addition to hepatocytes, are infected by HCV and support replication (4, 9, 20, 44, 69, 72, 74). If infected, macrophages may also contribute to the early induction of type I IFN signaling through RIG-1 and MDA-5.

FIG. 2.

Macrophages in HCV (A) and HBV (B) infections. (A) HCV is detected in hepatocytes by PRRs, including TLR3 and TLR8, and a cellular IFN response is triggered but blunted (dashed line) by viral interference at multiple points. Viral particles are released from hepatocytes and extracellular HCV RNA, and proteins influence macrophage biology either directly by binding (core/TLR2) or interference (gC1qR and TLR4) or through endosomal TLRs after uptake of viral particles. Macrophages become activated (increasing expression of CD14 and CD68) and produce chemokines and the cytokines IL-10 and TNF-α but less IL-12. These result in pDC apoptosis, decreased T-cell proliferation, and fibrogenesis (not shown). (B) In hepatocytes, HBV replicates within nucleocapsid particles, escaping detection by hepatocyte PRRs. Therefore, there are no transcription changes in the hepatocytes. Viral particles are released from hepatocytes and HBV DNA, and proteins influence macrophage biology through intracellular and surface receptors. Viral HBcAG (capsid) interferes with TLR2, leading to increased cytokine (IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α) production. HBV particles taken up by macrophages are recognized by endosomal TLRs, leading to chemokine production, resulting in recruitment of antigen-nonspecific mononuclear cells, NK cells, and pDCs (not shown). MΦ, macrophage.

HCV, unlike HBV, spreads rapidly in the liver. Therefore, it is likely that during the early stages of HCV infection and in the later stages of HBV infection, KCs (and other cells) are exposed to free viral nucleic acids and proteins. KCs and macrophages express TLR1 through TLR6 and TLR8 (87). Thus, TLR3 and/or TLR8 (located in late endosomes and lysosomes), which are activated by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA; TLR3) and single-stranded RNA (TLR8), likely recognize HCV via phagocytosis, become activated, and contribute to the induction of type I IFNs (Fig. 2). In the case of HBV infection, exactly which TLRs detect viral infection have not been delineated, though it is likely that phagocytosed viral particles detected by TLR8 trigger innate activation of macrophages. It has been suggested that HBcAg can bind macrophages via TLR2 and activate TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 expression (10), although in an immortalized human hepatocyte cell line transgenic for HBV it is specifically TLR3 agonists that inhibit HBV replication in isolated KCs through an IFN-β-dependent mechanism (97). The role of TLRs in combating HBV infection has been generally demonstrated by using a transgenic mouse model of HBV infection, where stimulation of most TLRs inhibits viral replication (33).

Several studies report that HCV can interfere with type I IFN signaling, in particular through interfering with pathways downstream of TLR3 (1, 30, 46, 62; reviewed in references 5 and 82) (Fig. 2A). Given that some type I IFN responses are observed in HCV infections, this finding suggests that the interference is not 100% but that the resultant response is too weak or too late to be effective. Nevertheless, therapeutic IFN-α can lead to the elimination of HCV in chronic infection.

Macrophages, including liver macrophages, upregulate their antigen-presenting phenotype in response to IFN-γ (88), leading to several-hundred-fold-increased expression of MHC-II (19). In HCV infection, most KCs express high levels of MHC-II molecules compatible with this phenotype (8, 38). MHC-II allows antigen presentation to CD4 T cells, but macrophages are also able to cross-present viral epitopes to CD8 cells. Here, cell-associated particulate viral antigen and viral dsRNA are taken up by macrophages, degraded in phagosomes, and cross-presented via MHC-I (2). This cross-priming or cross-presentation could provide an efficient means for viral antigens within dead cells to be presented to T cells by uninfected macrophages, thereby inducing adaptive immunity or facilitating activation of primed HCV-specific T cells (26). Indeed, cross-priming of viral dsRNA seems to be essential for the priming of cytotoxic T cells (76). However, in the absence of co-stimulatory molecules, cross-presentation of antigens by macrophages is more likely to promote tolerance in naïve T cells (3), which might play a role in HBV- and/or HCV-induced hepatitis, but data on these diseases are lacking.

In summary, HCV evades by antagonizing the immune response, whereas HBV hides from detection by the early immune system, including macrophages, and both viruses lead to persistent liver infections in many cases.

MACROPHAGES DETERMINE CELLULAR AND CYTOKINE MILIEU IN HCV- AND HBV-INFECTED LIVERS

In the murine cytomegalovirus (75) and Listeria monocytogenes (11, 42) models of liver disease, it has been shown that KCs and macrophages integrate a cascade of innate inflammatory events bridging the innate and adaptive immune responses: type I IFN-dependent CCL2 produced by KCs recruits circulating monocytes to the liver, where they produce CCL3 (75). CCL3 recruits NK cells producing high levels of IFN-γ, which triggers widespread classical activation of macrophages, inducing CXCL9 production, which in combination with CCL3 promotes recruitment of CD4+ T cells (75, 99). Additionally, based on general immunology research, immune responses are expected to be further amplified by KCs and macrophages as follows: KC-secreted IL-12 and IL-18 should ensure that virus-specific CD4+ T cells differentiate into type 1 helper (Th1) cells, which secrete IFN-γ, creating an activating feedback loop between KCs and Th1 cells and promoting infiltration of more T cells (47) (Fig. 1); type I IFNs, released from hepatocytes (and KCs), should promote the expansion and activity of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (84). Cell-to-cell interactions between macrophages and T cells which are complementary to the primary T-cell receptor-MHC-II interaction by CD40 (on macrophages) and CD40L (on T cells) should result in bilateral signaling; the macrophages produce more IL-2, TNF-α, and nitric oxide and increase MHC-II expression, while the Th cells produce more IFN-γ (47, 50).

Such a cascade would be difficult to demonstrate in human HCV or HBV infection. However, in HCV-infected chimpanzees, a comparable IFN-α response is found in all animals, but resultant chemokine- and IFN-γ-induced genes are correlated with viral elimination (85). This suggests that the early immune cascade that will include KCs is crucial in determining outcome. Not surprisingly, histological analysis of chronically HCV-infected livers demonstrates a dramatic increase in total as well as antigen-presenting macrophages in HCV infection (38, 53). Activated macrophages are found immunohistochemically in clusters with CD4+ T cells (8). Furthermore, on microarrays, genes of macrophage activation are very prominent in chronic HCV-infected liver (80). KC-derived chemokines (CCL3) are important in the recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs) (52, 99) and NK cells (which correlate with the outcome of HCV infection [39]). Moreover, KCs regulate DC migration into Disse's space and to lymph, which is vital for antigen presentation and the development of adaptive immune responses (63, 99).

A number of studies indicate aberrant macrophage function in chronically HCV- and HBV-infected individuals. In HBeAg-positive HBV infection, TLR2 expression in KCs is reduced (93), perhaps suppressing immune surveillance. Also, activated macrophages produce less TNF-α in vitro when exposed to lipopolysaccharide (TLR4 ligand) in the presence of HBV particles (61), and specifically, HBsAg binds to macrophages, inhibiting lipopolysaccharide-induced macrophage activities such as IL-12 production. Similarly, via interactions with gC1qR (a surface complement receptor), the HCV core protein inhibits TLR4-induced production of IL-12 by macrophages (94). Peripheral blood monocytes taken from HCV-infected patients preferentially express IL-10 upon exposure to recombinant HCV, which may contribute to reduced T-cell responses (96) and exhibit defective responses to TLR3 and TLR4 ligands (92). It is currently not clear whether these cells are functionally impaired by the virus or whether they have adapted an altered and reversible phenotype due to external stimuli (plasticity). Evidence for a direct effect is HCV core protein binding surface-expressed TLR2, which has been suggested to bias macrophage activation toward secretion of IL-10 and TNF-α (14, 16) (Fig. 2A). This cytokine combination is proposed to predispose plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) to apoptosis and low IFN-α production when exposed to TLR9 ligands (CpG DNA). The HCV core (32, 58), NS4A, NS4B (35), and NS5A (6, 25, 37, 66) have all been shown to induce CXCL8 expression in vitro. CXCL8 is elevated in the sera of HCV-infected patients (35, 54, 67, 71) and may inhibit the antiviral activity of IFNs (35, 66) and/or exacerbate inflammation (32, 35). Furthermore, when mixed with T cells, HCV core protein-expressing macrophage cell lines are less effective at promoting proliferation and IFN-γ production in T cells (45).

In summary, HBV and HCV, via an assortment of mechanisms, disturb immune responses and establish chronic infections, with macrophages as key regulators of the early immune responses being targeted by both viruses.

CONTRIBUTION OF MACROPHAGES TO LIVER INFLAMMATION

Characteristic pathological features of chronic HBV and HCV infections are chronic inflammation and apoptosis of infected and bystander hepatocytes (70, 82). KCs and macrophages are thought to be major contributors of bystander killing. In HCV infection, recently recruited (MAC387+) macrophages are increased in the focal areas of erosions (40, 53), and KC-derived IL-18 correlates with hepatitis and liver injury (53). Similarly, in HBV infection, more activated KCs expressing FasL are observed during episodes of liver damage (89), and activated KCs together with oval cells have been described in areas of inflammation and regeneration (81). Indeed, CD68 (macrophage marker) and CD14 (activated macrophages [27]) are both upregulated in viral hepatitis and correlate with liver injury (49, 53, 91, 98). It has been proposed that in chronic HCV infection, a combination of viral (e.g., serum HCV core protein) and host (e.g., IFN-γ and unphagocytosed endotoxins) factors cause KCs and recruited macrophages to be continuously and inappropriately activated (15). Activated KCs potentially kill hepatocytes via several mechanisms. KC-derived TNF-α is known to be injurious to hepatocytes in various models of T-cell-dependent acute liver damage (65), and KC expression of FasL may also promote hepatocyte apoptosis (42, 65). Local production of nitric oxide and ROS by activated macrophages may also contribute to bystander hepatocyte cell death (42).

MACROPHAGES INFLUENCE LIVER FIBROSIS AND CIRRHOSIS AND CANCER

Important complications of HBV and HCV infections are fibrosis and cirrhosis and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). KCs produce profibrogenic factors (e.g., transforming growth factor β and platelet-derived growth factor) (77) and yet also represent a major source of enzymes and factors important for matrix breakdown and turnover (collagenase, metalloproteinases, and IL-6) (64, 78, 79). Whether KCs exert a pro- or antifibrogenic effect depends on their cytokine environment (18, 21) and on interactions with stellate cells and hepatocytes (42). The serum- and glycocorticoid-regulated kinase is induced by transforming growth factor β and is associated with fibronectin formation, and in HBV and HCV infections, serum- and glycocorticoid-regulated kinase is upregulated in activated KCs, suggesting a profibrotic effect in these diseases (24). In a transgenic mouse model of HBV infection with hepatic HBV envelope protein expression, KCs exhibiting high levels of superoxides are observed specifically beside proliferating hepatocytes (29). HCV core- and NS5A-induced ROS and nitric oxide produced by activated KCs may also promote DNA damage in hepatocytes and induce oncogenesis (48). In addition, it has recently been postulated that KC-derived IL-6 contributes to hepatocyte proliferation and HCC development and that estrogen inhibition of IL-6 production reduces HCC risk in females (60). Therefore, KCs are not only relevant in HBV- and HCV-induced inflammation but also in the development of associated fibrosis and HCC. One study of KC depletion leading to attenuated liver injury (23) suggested an adverse net effect of liver macrophages, but the possible influence of macrophages will depend on their phenotypes and activation status.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Liver macrophages and KCs contribute to the tolerogenic environment of the undiseased liver and influence every stage of virus-induced liver disease. They recognize viral antigens and initiate the innate immune response, of which they are a major component. KCs determine the cellular and cytokine milieu of the virally infected liver and thus play a major pathological role in chronic virus-associated diseases. Future research is necessary to answer many of the unresolved questions relating to macrophages in HCV and HBV infections, such as the following. Are monocytes and macrophages productively infected by HCV, and is this a significant parameter in immune escape by HCV? Do liver macrophages function efficiently during HCV and/or HBV disease, and can they be a target for immune therapy to control HBV and/or HCV disease?

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge B. Rehermann, S. J. Forbes, and J. Iredale for helpful discussions at various stages of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, T., Y. Kaname, I. Hamamoto, Y. Tsuda, X. Wen, S. Taguwa, K. Moriishi, O. Takeuchi, T. Kawai, T. Kanto, N. Hayashi, S. Akira, and Y. Matsuura. 2007. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A modulates the Toll-like receptor-MyD88-dependent signaling pathway in macrophage cell lines. J. Virol. 818953-8966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellone, M., G. Iezzi, P. Rovere, G. Galati, A. Ronchetti, M. P. Protti, J. Davoust, C. Rugarli, and A. A. Manfredi. 1997. Processing of engulfed apoptotic bodies yields T cell epitopes. J. Immunol. 1595391-5399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilzer, M., F. Roggel, and A. L. Gerbes. 2006. Role of Kupffer cells in host defense and liver disease. Liver Int. 261175-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blight, K., R. Trowbridge, R. Rowland, and E. Gowans. 1992. Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA by in situ hybridization. Liver 12286-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bode, J. G., E. D. Brenndorfer, and D. Haussinger. 2007. Subversion of innate host antiviral strategies by the hepatitis C virus. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 462254-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonte, D., C. Francois, S. Castelain, C. Wychowski, J. Dubuisson, E. F. Meurs, and G. Duverlie. 2004. Positive effect of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein on viral multiplication. Arch. Virol. 1491353-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowen, D. G., and C. M. Walker. 2005. Adaptive immune responses in acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Nature 436946-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgio, V. L., G. Ballardini, M. Artini, M. Caratozzolo, F. B. Bianchi, and M. Levrero. 1998. Expression of co-stimulatory molecules by Kupffer cells in chronic hepatitis of hepatitis C virus etiology. Hepatology 271600-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caussin-Schwemling, C., C. Schmitt, and F. Stoll-Keller. 2001. Study of the infection of human blood derived monocyte/macrophages with hepatitis C virus in vitro. J. Med. Virol. 6514-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper, A., G. Tal, O. Lider, and Y. Shaul. 2005. Cytokine induction by the hepatitis B virus capsid in macrophages is facilitated by membrane heparan sulfate and involves TLR2. J. Immunol. 1753165-3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cousens, L. P., and E. J. Wing. 2000. Innate defenses in the liver during Listeria infection. Immunol. Rev. 174150-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curbishley, S. M., B. Eksteen, R. P. Gladue, P. Lalor, and D. H. Adams. 2005. CXCR 3 activation promotes lymphocyte transendothelial migration across human hepatic endothelium under fluid flow. Am. J. Pathol. 167887-899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Fougerolles, A. R., G. Chi-Rosso, A. Bajardi, P. Gotwals, C. D. Green, and V. E. Koteliansky. 2000. Global expression analysis of extracellular matrix-integrin interactions in monocytes. Immunity 13749-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolganiuc, A., S. Chang, K. Kodys, P. Mandrekar, G. Bakis, M. Cormier, and G. Szabo. 2006. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein-induced, monocyte-mediated mechanisms of reduced IFN-α and plasmacytoid dendritic cell loss in chronic HCV infection. J. Immunol. 1776758-6768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolganiuc, A., O. Norkina, K. Kodys, D. Catalano, G. Bakis, C. Marshall, P. Mandrekar, and G. Szabo. 2007. Viral and host factors induce macrophage activation and loss of toll-like receptor tolerance in chronic HCV infection. Gastroenterology 1331627-1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolganiuc, A., S. Oak, K. Kodys, D. T. Golenbock, R. W. Finberg, E. Kurt-Jones, and G. Szabo. 2004. Hepatitis C core and nonstructural 3 proteins trigger toll-like receptor 2-mediated pathways and inflammatory activation. Gastroenterology 1271513-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyle, A. G., G. Herbein, L. J. Montaner, A. J. Minty, D. Caput, P. Ferrara, and S. Gordon. 1994. Interleukin-13 alters the activation state of murine macrophages in vitro: comparison with interleukin-4 and interferon-gamma. Eur. J. Immunol. 241441-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffield, J. S., S. J. Forbes, C. M. Constandinou, S. Clay, M. Partolina, S. Vuthoori, S. Wu, R. Lang, and J. P. Iredale. 2005. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J. Clin. Investig. 11556-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrt, S., D. Schnappinger, S. Bekiranov, J. Drenkow, S. Shi, T. R. Gingeras, T. Gaasterland, G. Schoolnik, and C. Nathan. 2001. Reprogramming of the macrophage transcriptome in response to interferon-γ and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: signaling roles of nitric oxide synthase-2 and phagocyte oxidase. J. Exp. Med. 1941123-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falcón, V., N. Acosta-Rivero, M. Shibayama, G. Chinea, J. V. Gavilondo, M. C. de la Rosa, I. Menendez, B. Gra, S. Duenas-Carrera, A. Vina, W. Garcia, M. Gonzalez-Bravo, J. Luna-Munoz, M. Miranda-Sanchez, J. Morales-Grillo, J. Kouri, and V. Tsutsumi. 2005. HCV core protein localizes in the nuclei of nonparenchymal liver cells from chronically HCV-infected patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 3291320-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fallowfield, J. A., M. Mizuno, T. J. Kendall, C. M. Constandinou, R. C. Benyon, J. S. Duffield, and J. P. Iredale. 2007. Scar-associated macrophages are a major source of hepatic matrix metalloproteinase-13 and facilitate the resolution of murine hepatic fibrosis. J. Immunol. 1785288-5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenton, M. J., J. A. Buras, and R. P. Donnelly. 1992. IL-4 reciprocally regulates IL-1 and IL-1 receptor antagonist expression in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 1491283-1288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferré, N., and J. Claria. 2006. New insights into the regulation of liver inflammation and oxidative stress. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 61321-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fillon, S., K. Klingel, S. Warntges, M. Sauter, S. Gabrysch, S. Pestel, V. Tanneur, S. Waldegger, A. Zipfel, R. Viebahn, D. Haussinger, S. Broer, R. Kandolf, and F. Lang. 2002. Expression of the serine/threonine kinase hSGK1 in chronic viral hepatitis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 1247-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girard, S., P. Shalhoub, P. Lescure, A. Sabile, D. E. Misek, S. Hanash, C. Brechot, and L. Beretta. 2002. An altered cellular response to interferon and up-regulation of interleukin-8 induced by the hepatitis C viral protein NS5A uncovered by microarray analysis. Virology 295272-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon, S. 2003. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 323-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon, S., and P. R. Taylor. 2005. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5953-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guidotti, L. G., and F. V. Chisari. 2006. Immunobiology and pathogenesis of viral hepatitis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 123-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagen, T. M., S. Huang, J. Curnutte, P. Fowler, V. Martinez, C. M. Wehr, B. N. Ames, and F. V. Chisari. 1994. Extensive oxidative DNA damage in hepatocytes of transgenic mice with chronic active hepatitis destined to develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9112808-12812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helbig, K. J., E. Yip, E. M. McCartney, N. S. Eyre, and M. R. Beard. 2008. A screening method for identifying disruptions in interferon signaling reveals HCV NS3/4a disrupts Stat-1 phosphorylation. Antivir. Res. 77169-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heydtmann, M., P. Shields, G. McCaughan, and D. Adams. 2001. Cytokines and chemokines in the immune response to hepatitis C infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 14279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoshida, Y., N. Kato, H. Yoshida, Y. Wang, M. Tanaka, T. Goto, M. Otsuka, H. Taniguchi, M. Moriyama, F. Imazeki, O. Yokosuka, T. Kawabe, Y. Shiratori, and M. Omata. 2005. Hepatitis C virus core protein and hepatitis activity are associated through transactivation of interleukin-8. J. Infect. Dis. 192266-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isogawa, M., M. D. Robek, Y. Furuichi, and F. V. Chisari. 2005. Toll-like receptor signaling inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in vivo. J. Virol. 797269-7272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jakubzick, C., E. S. Choi, S. L. Kunkel, B. H. Joshi, R. K. Puri, and C. M. Hogaboam. 2003. Impact of interleukin-13 responsiveness on the synthetic and proliferative properties of Th1- and Th2-type pulmonary granuloma fibroblasts. Am. J. Pathol. 1621475-1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadoya, H., M. Nagano-Fujii, L. Deng, N. Nakazono, and H. Hotta. 2005. Nonstructural proteins 4A and 4B of hepatitis C virus transactivate the interleukin 8 promoter. Microbiol. Immunol. 49265-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanto, T., and N. Hayashi. 2006. Immunopathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection: multifaceted strategies subverting innate and adaptive immunity. Intern. Med. 45183-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khabar, K. S., and S. J. Polyak. 2002. Hepatitis C virus-host interactions: the NS5A protein and the interferon/chemokine systems. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 221005-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khakoo, S. I., P. N. Soni, K. Savage, D. Brown, A. P. Dhillon, L. W. Poulter, and G. M. Dusheiko. 1997. Lymphocyte and macrophage phenotypes in chronic hepatitis C infection. Correlation with disease activity. Am. J. Pathol. 150963-970. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khakoo, S. I., C. L. Thio, M. P. Martin, C. R. Brooks, X. Gao, J. Astemborski, J. Cheng, J. J. Goedert, D. Vlahov, M. Hilgartner, S. Cox, A. M. Little, G. J. Alexander, M. E. Cramp, S. J. O'Brien, W. M. Rosenberg, D. L. Thomas, and M. Carrington. 2004. HLA and NK cell inhibitory receptor genes in resolving hepatitis C virus infection. Science 305872-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kluth, D. C., L. P. Erwig, and A. J. Rees. 2004. Multiple facets of macrophages in renal injury. Kidney Int. 66542-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knolle, P. A., and G. Gerken. 2000. Local control of the immune response in the liver. Immunol. Rev. 17421-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kolios, G., V. Valatas, and E. Kouroumalis. 2006. Role of Kupffer cells in the pathogenesis of liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 127413-7420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lalor, P. F., and D. H. Adams. 2002. The liver: a model of organ-specific lymphocyte recruitment. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 41-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laskus, T., M. Radkowski, D. M. Adair, J. Wilkinson, A. C. Scheck, and J. Rakela. 2005. Emerging evidence of hepatitis C virus neuroinvasion. Aids 19(Suppl. 3)S140-S144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee, C. H., Y. H. Choi, S. H. Yang, C. W. Lee, S. J. Ha, and Y. C. Sung. 2001. Hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits interleukin 12 and nitric oxide production from activated macrophages. Virology 279271-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li, K., E. Foy, J. C. Ferreon, M. Nakamura, A. C. Ferreon, M. Ikeda, S. C. Ray, M. Gale, Jr., and S. M. Lemon. 2005. Immune evasion by hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease-mediated cleavage of the Toll-like receptor 3 adaptor protein TRIF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1022992-2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma, J., T. Chen, J. Mandelin, A. Ceponis, N. E. Miller, M. Hukkanen, G. F. Ma, and Y. T. Konttinen. 2003. Regulation of macrophage activation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 602334-2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Majano, P. L., and C. Garcia-Monzon. 2003. Does nitric oxide play a pathogenic role in hepatitis C virus infection? Cell Death Differ. 10(Suppl. 1)S13-S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marrogi, A. J., M. K. Cheles, and M. A. Gerber. 1995. Chronic hepatitis C. Analysis of host immune response by immunohistochemistry. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 119232-237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mathur, R. K., A. Awasthi, and B. Saha. 2006. The conundrum of CD40 function: host protection or disease promotion? Trends Parasitol. 22117-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matlack, R., K. Yeh, L. Rosini, D. Gonzalez, J. Taylor, D. Silberman, A. Pennello, and J. Riggs. 2006. Peritoneal macrophages suppress T-cell activation by amino acid catabolism. Immunology 117386-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsuno, K., H. Nomiyama, H. Yoneyama, and R. Uwatoku. 2002. Kupffer cell-mediated recruitment of dendritic cells to the liver crucial for a host defense. Dev. Immunol. 9143-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGuinness, P. H., D. Painter, S. Davies, and G. W. McCaughan. 2000. Increases in intrahepatic CD68 positive cells, MAC387 positive cells, and proinflammatory cytokines (particularly interleukin 18) in chronic hepatitis C infection. Gut 46260-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mihm, U., E. Herrmann, U. Sarrazin, M. von Wagner, B. Kronenberger, S. Zeuzem, and C. Sarrazin. 2004. Association of serum interleukin-8 with virologic response to antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 40845-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mills, C. D., K. Kincaid, J. M. Alt, M. J. Heilman, and A. M. Hill. 2000. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J. Immunol. 1646166-6173.10843666 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Monney, L., C. A. Sabatos, J. L. Gaglia, A. Ryu, H. Waldner, T. Chernova, S. Manning, E. A. Greenfield, A. J. Coyle, R. A. Sobel, G. J. Freeman, and V. K. Kuchroo. 2002. Th1-specific cell surface protein Tim-3 regulates macrophage activation and severity of an autoimmune disease. Nature 415536-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore, K. W., R. de Waal Malefyt, R. L. Coffman, and A. O'Garra. 2001. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19683-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moorman, J. P., S. M. Fitzgerald, D. C. Prayther, S. A. Lee, D. S. Chi, and G. Krishnaswamy. 2005. Induction of p38- and gC1qR-dependent IL-8 expression in pulmonary fibroblasts by soluble hepatitis C core protein. Respir. Res. 6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mosser, D. M. 2003. The many faces of macrophage activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73209-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Naugler, W. E., T. Sakurai, S. Kim, S. Maeda, K. Kim, A. M. Elsharkawy, and M. Karin. 2007. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science 317121-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oquendo, J., S. Karray, P. Galanaud, and M. A. Petit. 1997. Effect of hepatitis B virus on tumour necrosis factor (TNF alpha) gene expression in human THP-1 monocytic and Namalwa B-cell lines. Res. Immunol. 148399-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Otsuka, M., N. Kato, M. Moriyama, H. Taniguchi, Y. Wang, N. Dharel, T. Kawabe, and M. Omata. 2005. Interaction between the HCV NS3 protein and the host TBK1 protein leads to inhibition of cellular antiviral responses. Hepatology 411004-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parker, G. A., and C. A. Picut. 2005. Liver immunobiology. Toxicol. Pathol. 3352-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park-Min, K. H., T. T. Antoniv, and L. B. Ivashkiv. 2005. Regulation of macrophage phenotype by long-term exposure to IL-10. Immunobiology 21077-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Polakos, N. K., J. C. Cornejo, D. A. Murray, K. O. Wright, J. J. Treanor, I. N. Crispe, D. J. Topham, and R. H. Pierce. 2006. Kupffer cell-dependent hepatitis occurs during influenza infection. Am. J. Pathol. 1681169-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Polyak, S. J., K. S. Khabar, D. M. Paschal, H. J. Ezelle, G. Duverlie, G. N. Barber, D. E. Levy, N. Mukaida, and D. R. Gretch. 2001. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein induces interleukin-8, leading to partial inhibition of the interferon-induced antiviral response. J. Virol. 756095-6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Polyak, S. J., K. S. Khabar, M. Rezeiq, and D. R. Gretch. 2001. Elevated levels of interleukin-8 in serum are associated with hepatitis C virus infection and resistance to interferon therapy. J. Virol. 756209-6211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Racanelli, V., and B. Rehermann. 2006. The liver as an immunological organ. Hepatology 43S54-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Radkowski, M., A. Bednarska, A. Horban, J. Stanczak, J. Wilkinson, D. M. Adair, M. Nowicki, J. Rakela, and T. Laskus. 2004. Infection of primary human macrophages with hepatitis C virus in vitro: induction of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin 8. J. Gen. Virol. 8547-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rehermann, B., and M. Nascimbeni. 2005. Immunology of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5215-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ren, Y., R. T. Poon, H. T. Tsui, W. H. Chen, Z. Li, C. Lau, W. C. Yu, and S. T. Fan. 2003. Interleukin-8 serum levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: correlations with clinicopathological features and prognosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 95996-6001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Revie, D., R. S. Braich, D. Bayles, N. Chelyapov, R. Khan, C. Geer, R. Reisman, A. S. Kelley, J. G. Prichard, and S. Z. Salahuddin. 2005. Transmission of human hepatitis C virus from patients in secondary cells for long term culture. Virol. J. 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ricote, M., A. C. Li, T. M. Willson, C. J. Kelly, and C. K. Glass. 1998. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature 39179-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Royer, C., A. M. Steffan, M. C. Navas, A. Fuchs, D. Jaeck, and F. Stoll-Keller. 2003. A study of susceptibility of primary human Kupffer cells to hepatitis C virus. J. Hepatol. 38250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Salazar-Mather, T. P., and K. L. Hokeness. 2006. Cytokine and chemokine networks: pathways to antiviral defense. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 30329-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schulz, O., S. S. Diebold, M. Chen, T. I. Naslund, M. A. Nolte, L. Alexopoulou, Y. T. Azuma, R. A. Flavell, P. Liljestrom, and C. Reis e Sousa. 2005. Toll-like receptor 3 promotes cross-priming to virus-infected cells. Nature 433887-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schwabe, R. F., E. Seki, and D. A. Brenner. 2006. Toll-like receptor signaling in the liver. Gastroenterology 1301886-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shapiro, S. D., E. J. Campbell, D. K. Kobayashi, and H. G. Welgus. 1990. Immune modulation of metalloproteinase production in human macrophages. Selective pretranslational suppression of interstitial collagenase and stromelysin biosynthesis by interferon-gamma. J. Clin. Investig. 861204-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shapiro, S. D., D. K. Kobayashi, A. P. Pentland, and H. G. Welgus. 1993. Induction of macrophage metalloproteinases by extracellular matrix. Evidence for enzyme- and substrate-specific responses involving prostaglandin-dependent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2688170-8175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith, M. W., Z. N. Yue, M. J. Korth, H. A. Do, L. Boix, N. Fausto, J. Bruix, R. L. Carithers, Jr., and M. G. Katze. 2003. Hepatitis C virus and liver disease: global transcriptional profiling and identification of potential markers. Hepatology 381458-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sobaniec-Lotowska, M. E., J. M. Lotowska, and D. M. Lebensztejn. 2007. Ultrastructure of oval cells in children with chronic hepatitis B, with special emphasis on the stage of liver fibrosis: the first pediatric study. World J. Gastroenterol. 132918-2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spengler, U., and J. Nattermann. 2007. Immunopathogenesis in hepatitis C virus cirrhosis. Clin. Sci. (London) 112141-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stein, M., S. Keshav, N. Harris, and S. Gordon. 1992. Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J. Exp. Med. 176287-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stetson, D. B., and R. Medzhitov. 2006. Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity 25373-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Su, A. I., J. P. Pezacki, L. Wodicka, A. D. Brideau, L. Supekova, R. Thimme, S. Wieland, J. Bukh, R. H. Purcell, P. G. Schultz, and F. V. Chisari. 2002. Genomic analysis of the host response to hepatitis C virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9915669-15674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sun, Z., T. Wada, K. Maemura, K. Uchikura, S. Hoshino, A. M. Diehl, and A. S. Klein. 2003. Hepatic allograft-derived Kupffer cells regulate T cell response in rats. Liver Transplant. 9489-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Szabo, G., P. Mandrekar, and A. Dolganiuc. 2007. Innate immune response and hepatic inflammation. Semin. Liver Dis. 27339-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Taams, L. S., L. W. Poulter, M. H. Rustin, and A. N. Akbar. 1999. Phenotypic analysis of IL-10-treated macrophages using the monoclonal antibodies RFD1 and RFD7. Pathobiology 67249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tang, T. J., J. Kwekkeboom, J. D. Laman, H. G. Niesters, P. E. Zondervan, R. A. de Man, S. W. Schalm, and H. L. Janssen. 2003. The role of intrahepatic immune effector cells in inflammatory liver injury and viral control during chronic hepatitis B infection. J. Viral Hepat. 10159-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Taylor, P. R., L. Martinez-Pomares, M. Stacey, H. H. Lin, G. D. Brown, and S. Gordon. 2005. Macrophage receptors and immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23901-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tomita, M., K. Yamamoto, H. Kobashi, M. Ohmoto, and T. Tsuji. 1994. Immunohistochemical phenotyping of liver macrophages in normal and diseased human liver. Hepatology 20317-325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Villacres, M. C., O. Literat, M. DeGiacomo, W. Du, T. Frederick, and A. Kovacs. 2008. Defective response to Toll-like receptor 3 and 4 ligands by activated monocytes in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Viral Hepat. 15137-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Visvanathan, K., N. A. Skinner, A. J. Thompson, S. M. Riordan, V. Sozzi, R. Edwards, S. Rodgers, J. Kurtovic, J. Chang, S. Lewin, P. Desmond, and S. Locarnini. 2007. Regulation of Toll-like receptor-2 expression in chronic hepatitis B by the precore protein. Hepatology 45102-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Waggoner, S. N., M. W. Cruise, R. Kassel, and Y. S. Hahn. 2005. gC1q receptor ligation selectively down-regulates human IL-12 production through activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. J. Immunol. 1754706-4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wieland, S., R. Thimme, R. H. Purcell, and F. V. Chisari. 2004. Genomic analysis of the host response to hepatitis B virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1016669-6674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Woitas, R. P., U. Petersen, D. Moshage, H. H. Brackmann, B. Matz, T. Sauerbruch, and U. Spengler. 2002. HCV-specific cytokine induction in monocytes of patients with different outcomes of hepatitis C. World J. Gastroenterol. 8562-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wu, J., M. Lu, Z. Meng, M. Trippler, R. Broering, A. Szczeponek, F. Krux, U. Dittmer, M. Roggendorf, G. Gerken, and J. F. Schlaak. 2007. Toll-like receptor-mediated control of HBV replication by nonparenchymal liver cells in mice. Hepatology 461769-1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yamamoto, K., M. Ohmoto, S. Matsumoto, T. Nagano, H. Kobashi, R. Okamoto, and T. Tsuji. 1995. Activated liver macrophages in human liver diseases. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10(Suppl. 1)S72-S76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yoneyama, H., and T. Ichida. 2005. Recruitment of dendritic cells to pathological niches in inflamed liver. Med. Mol. Morphol. 38136-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]