Menorrhagia is an important healthcare problem for women.1 In primary care menorrhagia is a considerable burden on resources and may ultimately lead to referral and surgery.1,2 There is a gap between research and practice, with best evidence not uniformly applied. The Anglia menorrhagia education study, a randomised controlled trial of an educational package delivered in 100 general practices in East Anglia between November 1995 and March 1996, evaluated whether education could change doctors' management.3 Practices reported individual cases, and behaviour of practices receiving education was compared with that in control practices. There were differences in the numbers reported from practices, raising concerns that underreporting might impact on the result. The publication of an Effective Health Care bulletin on menorrhagia coinciding with the start of the study was also a potential confounder.4 Furthermore, the reported data allowed comparison only between the two study groups and did not allow assessment of previous behaviour. It was therefore felt necessary to audit practice before and after the Anglia study intervention to validate its methods and findings, and to adjust for differences in practices, changes over time, and the effect of confounders.

Subjects, methods, and results

Four audit standards were set with local medical audit advisory groups: all women with menorrhagia under the age of 40 should receive tranexamic acid before hospital referral; no women should receive norethisterone as first line treatment for menorrhagia; all women with menorrhagia should receive tranexamic acid or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug as first line treatment; and women under 40 with menorrhagia should be referred only if appropriate medical treatment had been given. Notes of women aged 15-45 who first attended the year before or after the trial started were identified and audited by the study team. Data analysis calculated odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals with a random effects logistic regression model.5 This model compared the odds of referral or treatment in the intervention group of general practices (n=27) with the control group (n=25), adjusting for pre-intervention behaviour and the cluster randomised design of the original Anglia study.3

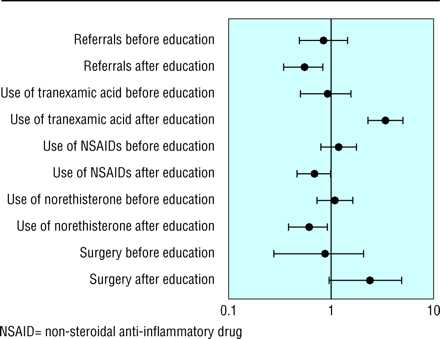

The results are presented as the odds of compliance with standards and absolute prescribing and referral rates from 662 cases of menorrhagia (figure). A woman was almost five times as likely to receive tranexamic acid in practices that received intervention as part of compliance with the standard (odds ratio 4.75; 1.42 to 12.1). These women were only half as likely to receive norethisterone as first line treatment (0.62; 0.38 to 0.92), with women nearly twice as likely to receive appropriate first line treatment (1.81; 1.24 to 2.53). Women referred from practices that received intervention were more likely to been given appropriate first line medication before referral (2.87; 1.14 to 6.15). Absolute data show a halving of referrals (0.537; 0.34 to 0.81), an increase in prescriptions of tranexamic acid (3.36; 2.21 to 4.96), and a reduction in norethisterone treatment (0.67; 0.46 to 0.95) for cases of menorrhagia. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were prescribed slightly less commonly in groups receiving intervention (0.61; 0.38 to 0.90). The odds of hysterectomy in the education group were increased by 2.33 (0.94 to 4.87). There were no demographic differences between practices.

Comment

The data show a positive change in behaviour among doctors as a result of education. The results also validate previously reported randomised controlled trial data.3 There were no before and after differences in control practices, indicating that external confounders had no effect. The trend towards an increased chance of hysterectomy in intervention groups may be because they had already received appropriate first line treatment. These women may proceed to more appropriate surgery as a result of this intervention.

Figure.

Odds ratios for various aspects of menorrhagia management both before and after educational intervention. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals

Acknowledgments

We thank all general practitioners who participated in the study and the regional postgraduate education office, Anglia and Oxford Health Authority, Fulbourn, Cambridge, without whose assistance it would not have been possible to complete the study.

Footnotes

Funding: The project was funded by the NHS Research and Development Health Technology Assessment programme.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Vessey M, Villard-MacKintosh L, McPherson K, Coulter A, Yeates D. The epidemiology of hysterectomy: findings of a large cohort study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:402–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coulter A, Bradlow J, Agass M, Martin-Bates C, Tulloch A. Outcomes of referrals to gynaecology outpatient clinics for menstrual problems: an audit of general practice records. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:789–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb13484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fender G, Prentice A, Gorst T, Nixon RM, Duffy SW, Day NE, et al. Randomised controlled trial of educational package on management of menorrhagia in primary care: the Anglia menorrhagia education study. BMJ. 1999;318:1246–1250. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7193.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Effective Health Care: The management of menorrhagia. York: NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; 1995. (No. 1). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nixon R, Duffy S, Fender GRK, Prevost T, Day N. Randomisation at the level of practice surgery: use of pre-intervention data and random effects models. Statistics in Med (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]