Abstract

TRIM5α is a retrovirus restriction factor in the host cell cytoplasm that blocks infection before provirus establishment. Restriction activity requires capsid (CA)-specific recognition by the PRYSPRY domain of TRIM5α. To better understand the restriction mechanism, nine charge-cluster-to-triple-alanine mutants in the TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain were assessed for CA-specific restriction activity. Five mutants distributed along the TRIM5α PRYSPRY primary sequence disrupted restriction activity against N-tropic murine leukemia virus and equine infectious anemia virus. Modeling of the TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain based on the crystal structures of PRYSPRY-19q13.4.1, GUSTAVUS, and TRIM21 identified a surface patch where disruptive mutants clustered. All mutants in this patch retained CA-binding activity, a reticular distribution in the cytoplasm, and steady-state protein levels comparable to those of the wild type. Residues in the essential patch are conserved in TRIM5α orthologues and in closely related paralogues. The same surface patch in the TRIM18 and TRIM20 PRYSPRY domains is the site of mutants causing Opitz syndrome and familial Mediterranean fever. These results indicate that, in addition to CA-specific binding, the PRYSPRY domain possesses a second function, possibly binding of a cofactor, that is essential for retroviral restriction activity by TRIM5α.

TRIM5α is a potent retroviral restriction factor that blocks retroviruses after cell entry but before integration. This antiretroviral activity is species specific. For example, the rhesus macaque orthologue acts potently against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (39), whereas TRIM5α from African green monkeys inhibits HIV-1, as well as other retroviruses, such as N-tropic murine leukemia virus (N-MLV), simian immunodeficiency virus, and equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) (15, 18, 24, 38, 50, 53). The human TRIM5α orthologue modestly blocks HIV-1 but efficiently inhibits N-MLV (15, 18, 31, 50). Depletion of the TRIM5α protein in human cells by RNA interference was shown to completely relieve the block to N-MLV, demonstrating that TRIM5α is required for the restriction of this retrovirus in human cells (15, 31, 35, 50, 53). In addition, exogenous expression of human TRIM5α in permissive cells, such as Crandall feline kidney (CRFK) fibroblasts or Mus dunni tail fibroblasts, imparts a block against N-MLV as potent as the one observed in human cells (15, 18, 31, 50, 53).

TRIM5 has three protein domains that are characteristic of TRIM family members: RING finger, B-box, and coiled-coil domains. The alpha isoform of TRIM5 contains an additional C-terminal PRYSPRY (or B30.2) domain. Sequence variation in the PRYSPRY domain accounts for the virus specificity of TRIM5α orthologues (37, 38, 41). In some cases, single-amino-acid changes in the PRYSPRY domain significantly alter the specificity of restriction (21, 41, 51).

Simple biochemical assays of protein-protein interaction have failed to detect TRIM5α binding to CA (6, 33). TRIM5α forms trimers in vitro which have been modeled to make multiple contacts with the hexameric CA lattice that constitutes the surface of the mature virion core (17, 22). Consistent with this model, noninfectious virus-like particles saturate TRIM5α-mediated restriction (44), but only if the particles bear a mature core from a restriction-sensitive virus (10, 45). Similarly, expression within target cells of gag, gag-pol, or gag fragments failed to saturate the restriction activity (33).

MLV strains bearing an arginine at CA residue 110 (so-called N-MLV) are highly susceptible to restriction by human TRIM5α, whereas MLV virions bearing glutamate in this position (B-tropic MLV [B-MLV]) are completely resistant to restriction (15, 18, 31, 50). An assay was developed in which human TRIM5α associated preferentially with the CA of restricted N-MLV, compared with the CA of the unrestricted B-MLV (33). This assay exploited the fact that retrovirion cores can be liberated from the viral membrane envelope by detergent (47). MLV was selected for study because, relative to HIV-1, MLV CA seems more tightly associated with the virion core (8, 13) and because N-MLV is the most sensitive reporter virus for human TRIM5α-mediated restriction (15, 18, 31, 50). N-MLV association with human TRIM5α was dependent on the PRYSPRY domain (33). Similarly, rhesus macaque TRIM5α associates with HIV-1 CA-like structures, and mutations in the PRYSPRY domain that abolished this association also resulted in loss of restriction activity (40). Therefore, while the N-terminal RING domain and B box are thought to mediate an effector function required for restriction activity, the PRYSPRY domain is viewed as the ligand-binding part of the protein.

Here, we sought to map surface amino acid residues in the PRYSPRY domain of human TRIM5α that are involved in N-MLV CA binding. For this purpose, a panel of nine charge-cluster-to-triple-alanine substitution mutants was generated. To our surprise, only one of these mutants disrupted binding. Instead, by placing our mutants on a three-dimensional model of the human TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain, we identified an exposed patch of residues that is required for restriction activity but dispensable for CA binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Human embryonic kidney fibroblasts (293T cells) and CRFK fibroblasts were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin.

Plasmids and mutagenesis.

pMIG is a murine stem cell virus (MSCV)-based bicistronic vector that directs the synthesis of green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosome entry site (46). pMIP was derived from pMIG by replacing the GFP coding sequence with that for puromycin acetyltransferase (34). pCIG3-N and pCIG3-B express gag and pol from N-MLV and B-MLV, respectively (7). pMD.G expresses the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (52). pCL-Eco is psi-minus Moloney MLV expressed from the cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter (25). The EIAV gag-pol vector pONY3.1 and the GFP-packaging vector pONY8.0 have been previously described (23). Human TRIM5α alanine substitution mutants (Table 1) were generated by two-step overlapping PCR and cloned into pMIP. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins were expressed by replacing GFP-myc of pEF/myc/cyto/GFP (Invitrogen) with GST coding sequence, followed by a linker encoding the Gly-Ser-Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly nonapeptide.

TABLE 1.

Properties of TRIM5α triple alanine substitution mutant proteins

| Namea | WT amino acids | Coding nucleotides

|

Activityb | CA bindingc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Mutant | ||||

| WT | + | + | |||

| 263 | KKP | AAG AAG GCC | GCG GCG GCA | + | + |

| 288 | FRE | TTT AGA GAG | GCT GCA GCG | + | + |

| 295 | RRY | CGA CGC TAC | GCA GCC GCC | − | − |

| 315 | EDK | GAA GAT AAG | GCA GCT GCG | + | + |

| 358 | KHY | AAA CAT TAC | GCA GCT GCC | − | + |

| 362 | EVD | GAG GTA GAC | GCG GCA GCC | − | + |

| 367 | KKT | AAG AAA ACT | GCG GCA GCT | − | + |

| 388 | EKN | GAA AAA AAT | GCA GCA GCT | + | + |

| 480 | RKC | AGA AAA TGT | GCA GCA GCT | − | + |

Triple alanine substitution mutants were named for the position of the first amino acid residue that was altered. WT, wild type.

Restriction activity specific for N-MLV in transduced CRFK cells. +, present; −, absent.

Binding of N-MLV CA to GST-TRIM5α fusion. +, present; −, absent.

Generation of TRIM5α-expressing CRFK cell lines.

Virus for transduction was produced by transfection of 293T cells with 5 μg pMD.G, 10 μg pCL-Eco, and 10 μg of pMIP encoding the various TRIM5α mutants. Virus was harvested 2 days after transfection, filtered (0.45 μm), and used to infect 5 × 104 CRFK cells in a 12-well plate in the presence of 5 μg/ml Polybrene. Pools of transduced cells were selected in 7.5 μg/ml puromycin.

Single-cycle infectivity assay.

N- and B-tropic GFP reporter viruses were produced by calcium phosphate transfection of 293T cells with 10 μg pCIG3-N or pCIG3-B, 10 μg pRetroQ-GFP (Clontech), and 5 μg pMD.G. EIAV reporter viruses were generated using 10 μg pONY3.1, 10 μg pONY8.0, and 5 μg pMD.G. Reporter virus stocks were harvested 2 days after transfection, filtered (0.45-μm pore size), and stored at −80°C. CRFK cells (5 × 104 per well) were seeded in 24-well plates and infected with serial dilutions of N- or B-MLV-GFP reporter virus; 48 h postinfection, the cells were trypsinized and fixed in 4% formaldehyde. Cells (104) from each sample were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the percentage of GFP-positive cells.

Western blotting.

Cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, and 5% glycerol. Samples were then boiled in 4× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer, and the proteins were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). After transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, the blots were probed with goat anti-FLAG epitope tag (horseradish peroxidase conjugated; Bethyl Laboratories), goat anti-MLV CA (a gift from S. P. Goff), rabbit anti-GST (Chemicon), or mouse anti-β-actin (Sigma).

CA-binding assay.

293T cells were transfected with GST-TRIM5α expression plasmids (one 10-cm plate per sample) and trypsinized 48 h posttransfection. Cells were harvested, washed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and incubated for 30 min in 1 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, and 5% glycerol, supplemented with Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablets). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the cleared lysate was added to 20 μl glutathione-Sepharose beads (G beads). Ten milliliters of N- or B-MLV reporter virus was concentrated by ultracentrifugation through a 25% sucrose cushion at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. The virus pellets were resuspended in 100 μl PBS and added to the G beads with TRIM5α-containing lysate. Samples were agitated at 4°C for 2 h and washed four times in lysis buffer. The G beads were resuspended in 10 μl 4× loading buffer and boiled for 8 min, and the proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed to detect MLV CA (p30) and GST-TRIM5α.

Capsid stability assay.

Ten milliliters of N- or B-MLV reporter virus was filtered and concentrated by ultracentrifugation through a 25% sucrose cushion at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. The virus pellets were resuspended in 100 μl PBS and normalized by exogenous reverse transcriptase assay. As a control, 50 μl of each virus preparation was boiled in 10% SDS for 5 min. 293T cells were trypsinized, washed in ice-cold PBS, and lysed for 30 min in 1 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, 5% glycerol, and protease inhibitors). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the cleared cell lysate (1 ml) was added to 50 μl of concentrated virus (N or B tropic) and to the 50 μl of denatured viruses. Samples were accelerated onto a 45% or 55% sucrose cushion at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. One hundred microliters from the upper fraction was harvested, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of ice-cold PBS. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed in Western blots with polyclonal antibody recognizing MLV CA.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

CRFK cells transduced to express FLAG-tagged human TRIM5α, the wild type or various mutants, were grown on glass coverslips. The cells were fixed at 25°C for 10 min with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS and permeabilized on ice for 2 min with 2% Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate. After being quenched with 0.1 M glycine in PBS at 25°C for 10 min, the cells were blocked for 30 min at 25°C with 10% goat serum and 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS before being incubated overnight with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma). The cells were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-anti-mouse secondary antibody and mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Vector laboratories). The cells were visualized with a 63× 1.4-numerical-aperture Leica HCX Planapochromat oil immersion objective using an inverted Leica DMI 6000 CS microscope fitted with a TCS SP5 laser scanning confocal system. Image analysis was performed using MetaMorph software provided by Universal Imaging Corp.

Structural alignment of PRYSPRY-19q13.4.1, GUSTAVUS, and TRIM21.

The crystal structures of the PRYSPRY domain from PRYSPRY-19q13.4.1 (Protein Data Bank [PDB] entry 2FBE; residue range, 11 to 184 of chain A) (14), GUSTAVUS (PDB entry 2FNJ; residue range, 35 to 83 and 88 to 233 of chain A) (49), and TRIM21 (PDB entry 2IWG; residue range, 2 to 182 of chain B) (16) were superimposed and aligned with StruPro (19) using an alpha carbon cutoff distance of 3.5 Å. The sequence of human TRIM5α was then combined with the structural alignment of PRYSPRY-19q13.4.1, GUSTAVUS, and TRIM21 using ClustalX (42). To localize insertions and deletions, generally in loop regions, the alignment was compared with a ClustalW (43) sequence-based multiple alignment of 10 characteristic psiBLAST (2) hits of all three aforementioned sequences. Additionally, the alignment was manually corrected, taking into account information from a secondary-structure prediction of TRIM5α obtained with NPS@ (9). The final alignment was then fed into the program Modeler 8 v2 (http://salilab.org/modeller), using 2FBE and 2FNJ as structural templates. One hundred models were built using the model and loop optimization procedures of the program. The resulting models were evaluated for stereochemical quality with PROCHECK (20). The best one was taken as the final model for the PRYSPRY domain of human TRIM5α. Pictures of the model were generated with PyMol v0.98.

RESULTS

Selective pullout of restriction-sensitive CA is not explained by differences in virion core stability.

Experimental conditions were previously identified under which CA from detergent-stripped virions could be detected in association with TRIM5α (33). Interaction in this assay was specific for the restriction-sensitive CA of N-MLV (compared with restriction-insensitive B-MLV), required the human TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain, and thus satisfied the expected parameters for retroviral restriction activity established in vivo. Nonetheless, the apparent binding specificity in this in vitro assay might be explained by differences in N-MLV and B-MLV core stabilities, as recently reported using the fate-of-capsid assay (29).

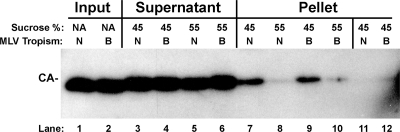

To determine if differential binding to TRIM5α resulted from differences in core stability, N-MLV and B-MLV virions were detergent stripped using the protocol from the in vitro binding experiment (33). The resulting particulate cores were then accelerated through 45% or 55% sucrose, as described for the fate-of-capsid assay (29). As expected in this assay, 55% sucrose severely limited detection of pelletable virion CA protein (Fig. 1). In all cases, the controls and 45% and 55% sucrose, the yields of N-MLV and B-MLV CA were identical (Fig. 1). This indicates that, under the conditions of the in vitro binding assay, N-MLV and B-MLV core stabilities are indistinguishable, and differential core stability does not explain the specific binding of N-MLV CA to human TRIM5α.

FIG. 1.

N-MLV and B-MLV virion cores exhibit comparable stabilities. N-MLV and B-MLV virions (N and B) were suspended in binding assay buffer containing Triton X-100 and NP-40 (33) and layered onto 45% or 55% sucrose cushions as indicated and as described previously (29). The input (lanes 1 and 2), postacceleration supernatant (lanes 3 to 6), and pellet (lanes 7 to 10) were processed by SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-MLV CA antibody. Lanes 11 and 12 show pellets for N-MLV and B-MLV virions, respectively, that had been boiled in SDS prior to centrifugation. NA, not applicable.

Charge-cluster-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis of the TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain.

To better understand the mechanism of retroviral restriction, the in vitro binding assay was exploited to map human TRIM5α PRYSPRY structural requirements for N-MLV CA binding. Several TRIM5α C-terminal truncation mutants of various lengths were generated, but failure to detect synthesis of these mutants by Western blotting precluded assessment in the CA-binding assay (data not shown).

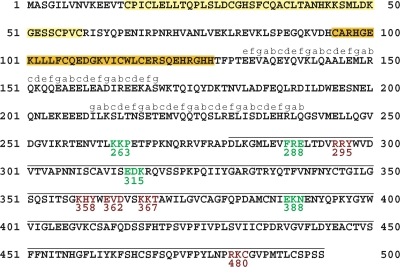

Charge-cluster-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis of the human TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain was attempted next. Clusters of at least two charged amino acids in any window of 3 residues were replaced with 3 alanine residues (3, 4, 11, 48). Such clusters of charged amino acids are likely to occupy positions on the surface of the protein (11), and replacement of such residues is less likely to disrupt the overall conformation and stability of the molecule (1, 12). The nine alanine substitution mutants that were engineered in this fashion are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Locations and restriction phenotypes of human TRIM5α surface-charge-to-triple-alanine PRYSPRY mutants. Amino acid residues 280 to 493 constitute the PRYSPRY domain and are indicated by a solid black line. Ring finger domain residues are highlighted in yellow. B-box residues are highlighted in orange. Paircoil-predicted coiled coils and their register (5) are indicated by lowercase letters. Mutants are named for the first of the three consecutive residues that were changed to alanine, e.g., mutant 263 is K263A/K264A/P265A. Green mutants exhibited wild-type restriction activity. Restriction activity was disrupted by red mutants.

Restriction activities of TRIM5α alanine substitution mutants.

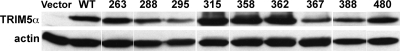

To assess the TRIM5α mutants for the ability to inhibit infection by N-MLV, nonrestrictive cat (CRFK) fibroblasts were transduced with bicistronic retroviral vectors encoding FLAG-tagged TRIM5α mutants and a puromycin resistance cassette. Each transfected population was grown as a pool of cells under puromycin selection, and steady-state levels of TRIM5α proteins were assessed by Western blotting (Fig. 3). The protein levels of the mutants were variable, though TRIM5α protein levels have not been found to correlate with the strength of restriction activity (34). Increase of TRIM5α protein by sodium butyrate, for example, was found not to increase restriction activity (53).

FIG. 3.

Steady-state protein levels for human TRIM5α mutants. CRFK cells were transduced with an empty retroviral vector (Vector) or with retroviral vectors encoding FLAG epitope fusions to wild-type TRIM5α (WT) or the indicated TRIM5α mutants (named according to the convention described in the legend to Fig. 1). Whole-cell lysates were probed in immunoblots with anti-FLAG and anti-actin antibodies.

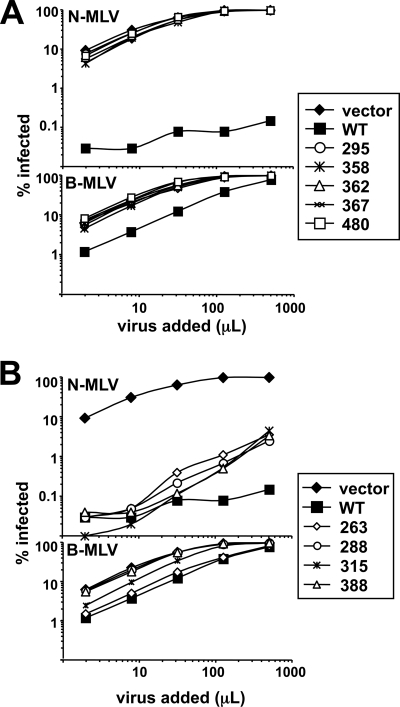

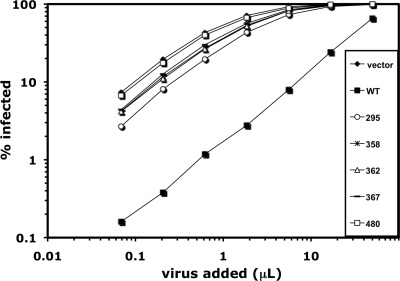

To measure the retroviral restriction activities of the TRIM5α alanine substitution mutants, pools of stable cat cell lines bearing each of the mutants were established with MSCV-derived vectors as previously described (34). Each pool of cells was transduced with serial dilutions of N- or B-MLV-GFP reporter viruses, and the percentage of infected cells was determined 2 days later. Compared to the empty-vector control, wild-type human TRIM5α restricted N-MLV 100- to 1,000-fold (Fig. 4). Relatively modest restriction of B-MLV by wild-type TRIM5α was observed, but this virus was not blocked by any of the mutants (Fig. 4). N-MLV restriction activity was completely disrupted by mutants 295, 358, 362, 367, and 480 (Fig. 4A). Mutants 263, 288, 315, and 388 possessed N-MLV restriction activities like that of the wild type (Fig. 4B), though a small defect in restriction activity for these mutants was evident at higher multiplicities of infection.

FIG. 4.

Restriction activities of human TRIM5α mutants. CRFK cells stably transduced in pools with the indicated TRIM5α mutants were infected with increasing amounts of N-MLV-GFP or B-MLV-GFP (left to right on the x axis). The percentage of GFP-positive cells (y axis) was determined 48 h later. TRIM5α mutants are clustered for presentation according to whether they lost restriction activity (A) or retained activity comparable to that of the wild type (WT) (B).

EIAV is one of the few retroviruses other than N-MLV that is known to be restricted by human TRIM5α (15). We examined the sensitivity of this virus to restriction by the TRIM5α mutants—295, 358, 362, 367, and 480—that were defective for restriction of N-MLV. Each of these mutants was severely compromised in its ability to restrict EIAV (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

EIAV restriction activities of selected human TRIM5α mutants. CRFK cells stably transduced in pools with the indicated TRIM5α mutants were infected with increasing amounts of EIAV-GFP (left to right on the x axis). The percentage of GFP-positive cells (y axis) was determined 48 h later. WT, wild type.

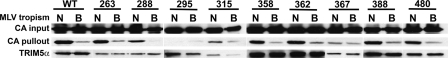

CA binding of TRIM5α mutants.

The abilities of the TRIM5α alanine mutants to bind N-MLV CA were assessed next, using the previously described in vitro binding assay (33). GST-TRIM5α fusions were transiently expressed in 293T cells, and MLV virions were added to the detergent-containing cell lysate. The TRIM5α-virus mixture was incubated with G beads, and after association of the GST-TRIM5α fusion proteins with the matrix, the pellet was probed by Western blotting for MLV CA.

GST fusions of the TRIM5α mutants were expressed at various levels, and each of them was assessed in the CA-binding assay (Fig. 6). CA protein in each reaction was determined by immunoblotting of aliquots taken directly after viral particles were added to the cell lysates but before G beads were added to the mixture (CA input). After the binding reaction, all proteins that remained associated with the G beads were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting. Membranes were first probed with anti-CA antibody (CA pullout) and subsequently with anti-GST antibody (TRIM5).

FIG. 6.

CA-binding activities of TRIM5α mutants. GST-TRIM5α fusion proteins were synthesized in 293T cells. The cells were lysed with Triton X-100 and NP-40, concentrated N- or B-MLV virions (N and B) were added, and the mixture was incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads. Proteins that remained associated with the beads were probed by Western blotting with anti-MLV CA and anti-GST antibodies. WT, wild type. The numbers represent the mutants.

As previously reported (33), wild-type human TRIM5α associated with the restricted N-MLV CA and much less so with the unrestricted B-MLV CA (Fig. 6). This result was obtained in 30 repetitions of this experiment; the amount of N-MLV CA protein associated with wild-type TRIM5α was proportional to the amount of GST-TRIM5α protein added to the binding reaction, and the relative amount of N-MLV CA bound, compared with the B-MLV CA bound, remained constant (data not shown).

Binding experiments with each of the TRIM5α mutants were repeated at least three times, always in parallel with the wild type (Fig. 6). CA protein was never detected in association with TRIM5α mutant 295, indicating a loss of CA-binding activity. The expression level of TRIM5α mutant 367 was relatively low, but no decrease in the efficiency of the N-MLV pullout was evident. All of the remaining mutants pulled down N-MLV with efficiency like that of the wild type and with comparable specificity relative to B-MLV. Though local concentrations at the site of CA-TRIM5α interaction within the cell are not known, it must not be forgotten that the recombinant TRIM5α protein used in these in vitro binding experiments was probably at levels significantly higher than those of the endogenous protein, and this might have driven interactions that would not occur in cells.

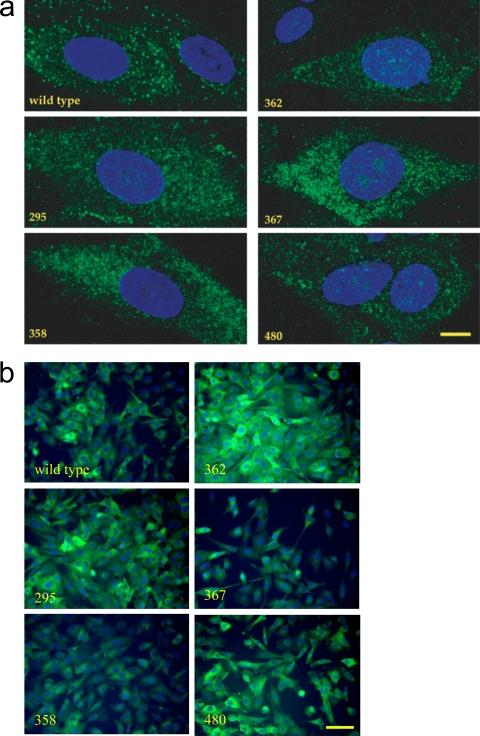

Imaging of TRIM5α mutants by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Despite the existence of reasonably sensitive anti-TRIM5 antibodies, the detection of endogenous TRIM5 by immunofluorescence has not been reported, presumably because the protein is synthesized at very low levels. When expressed from transgenes, TRIM5 has been reported to concentrate in large cytoplasmic bodies (32) or to exhibit a diffuse reticular pattern in the cytoplasm (27). The significance of the cytoplasmic bodies is not known and could be an artifact of overexpression. Several reports have in fact demonstrated full retroviral restriction activity due to TRIM5 in the absence of detectable cytoplasmic bodies (27, 28, 36).

The CRFK cell lines bearing TRIM5 mutants that lacked N-MLV restriction activity were examined by immunofluorescence using a confocal microscope. In all cases, a punctate cytoplasmic staining pattern was observed (Fig. 7). While, discrete cytoplasmic bodies were more prominent with the wild type, the mutants did not otherwise differ significantly from the wild type in their subcellular distributions (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

TRIM5α mutants defective for N-MLV restriction activity exhibit a punctate cytoplasmic distribution. Representative indirect immunofluorescence images of CRFK cells stably expressing either the wild-type or mutant FLAG-tagged human TRIM5α, as indicated, are shown. Fixed samples were stained with anti-FLAG antibody (green) and counterstained with DAPI to visualize the nuclear DNA (blue). (a) Two-dimensional maximum projections of dual-color z stacks containing 18 to 20 0.35-μm sections. Bar, 10 μm. (b) Low-power (10× objective) images showing fields of multiple cells. Bar, 100 μm.

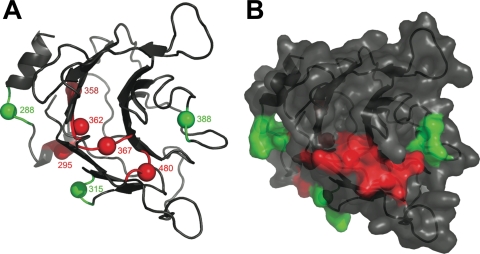

Homology model of the human TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain.

The structures of the PRYSPRY domains from PRYSPRY-19q13.4.1 (14), GUSTAVUS (49), and TRIM21 (16) have been solved by X-ray crystallography. Although the PRYSPRY domains of these three proteins show low sequence identity, the three-dimensional structures are very similar. The fold of these structures is a distorted β-sandwich formed by two antiparallel β-sheets. Residues within core structure β-strands are conserved among the butyrophilin and stonustoxin protein families, as well as among the tripartite-motif protein family that includes TRIM5α. Therefore, the PRYSPRY domain of human TRIM5α is likely to have the same fold.

Using the three crystal structures as templates (14, 16, 49), we created a model of the human TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain (Fig. 8). The sequence alignment of PRYSPRY-19q13.4.1, GUSTAVUS, TRIM21, and TRIM5α used as the basis for model building was generated with ClustalX (42) using a structural alignment of PRYSPRY-19q13.4.1, GUSTAVUS, and TRIM21 as a starting point. To be able to localize insertions and deletions, generally in loop regions, this alignment was compared with a multiple-sequence alignment of 10 characteristic psiBLAST (2) hits for each of the sequences. Finally, the alignment was manually corrected, taking into account information from a secondary-structure prediction of TRIM5α. In this way, a model structure that consists of 11 β-strands connected by long loops of variable length that form the β-sandwich core could be derived. The extended N-terminal part consists of two short α-helices adjacent to one of the β-sheets (Fig. 8).

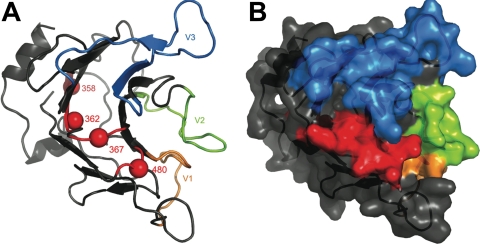

FIG. 8.

Locations of the triple alanine mutants on a model of the human TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain. The model is based on crystal structures for the PRYSPRY domains of PRYSPRY-19q13.4.1 (14), GUSTAVUS (49), and TRIM21 (16). Ribbon (A) and surface representation (B) diagrams show the positions of mutants that disrupted N-MLV restriction activity (red) or caused no significant reduction in N-MLV restriction activity (green).

The triple alanine mutation positions were then mapped onto the model of the PRYSPRY domain of human TRIM5α (Fig. 8). The model comprises eight of the nine alanine substitution mutants, because mutant 263 is located N-terminal of the model's starting point. Examination of the model revealed a loop region on one side of the β-sandwich as a hot spot for mutants that disrupt restriction activity (Fig. 8). The colocalization in three-dimensional space of these mutants, for example, 367 and 480, was not obvious from the primary structure (Fig. 8). Mutant 295, the only mutant with loss of the CA-binding phenotype, is located on a surface away from the hot spot, at the N terminus of the PRYSPRY domain model.

Mutant 388 had no effect on restriction activity against N-MLV and localized to a loop region with a high degree of sequence variability among TRIM5α orthologues (Fig. 8). These regions play roles in restriction against different retroviruses (26, 30). Mutants 288 and 315 localized some distance from this putative CA interaction site and had no influence on the restriction activity of human TRIM5α.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies utilized TRIM5α chimeras to demonstrate that the specificity determinants for retroviral restriction are in the PRYSPRY domain (27, 30, 51). This study investigated the restriction activities and CA-binding abilities of alanine substitution mutants in TRIM5α. By replacing clusters of charged amino acids in the C-terminal half of the TRIM5α protein with alanine residues, it was hoped that regions on the surface of the protein important for TRIM5α function as a restriction factor would be disrupted. It was first determined if the mutants could block N-MLV and EIAV infection when expressed in an otherwise permissive cell line. Then, the mutants were assessed for the ability to associate with N-MLV CA. Five of the nine mutants (the triple alanine mutants 295, 358, 362, 367, and 480) were defective for restriction activity, though only one of them, 295, was defective for binding to N-MLV CA.

The locations of the mutants were determined on a model of the TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain. According to this model, the disruptive mutants cluster together on the surface of the molecule, suggesting that they disrupt a putative surface that is essential for restriction activity (Fig. 8). Residues in this region of the TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain are highly conserved across TRIM5α orthologues and the closely related paralogues, TRIM22, TRIM34, and TRIM6 (Fig. 9). The functional significance of this region has not been described before, perhaps because previous studies focused on regions with maximal sequence variation. The conserved surface patch is clearly distinct from the previously described variable regions (Fig. 9 and 10). CA-binding and N-MLV restriction activities were disrupted by mutant 295. This finding is consistent with the current model of restriction, in which the interaction of TRIM5α with CA is a prerequisite for antiviral activity.

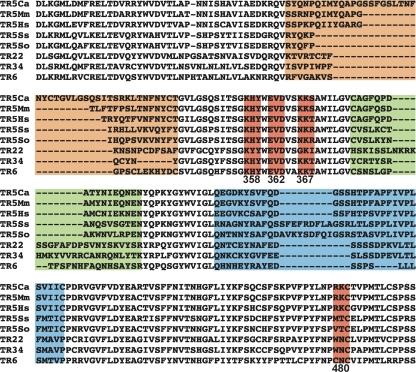

FIG. 9.

Amino acid sequence alignment of PRYSPRY domains from five TRIM5α (TR5) orthologues and from the human paralogues TRIM22 (TR22) (NP_006065), TRIM34 (TR34) (NP_569073), and TRIM6 (TR6) (AAH65575). Residues within the PRYSPRY variable loops are highlighted in orange (V1), green (V2), or blue (V3). Triple alanine mutants that disrupted N-MLV restriction activity but retained N-MLV CA-binding activity are highlighted in red. The sequences were aligned using ClustalW (43). Ca, Cercopithecus aethiops (AAT81167); Mm, Macaca mulatta (AAV91988); Hs, Homo sapiens (AAT48101); Ss, Saimiri sciureus (AAV91988); So, Saguinus oedipus (Q1ACD5).

FIG. 10.

An essential surface patch on the TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain is distinct from the variable loops. A model of the TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain was derived as described in the legend to Fig. 7. Triple alanine mutants that disrupted N-MLV restriction activity and defined the essential surface patch are shown in red. Orange, green, and blue shading indicate variable regions V1, V2, and V3, as previously described (37).

In a previous study, N-MLV restriction activity was conferred on rhesus monkey TRIM5α by substituting PRYSPRY variable loops from the human orthologue (30). In the context of these chimeric proteins, human TRIM5α residues 335 to 340, 405, and 406 were shown to be important for activity. Another study identified an important residue for N-MLV restriction in New World monkeys (26). This amino acid position corresponds to residue 343 in the human TRIM5α orthologue, a residue that was not altered here.

The vast majority of the mutants that lost restriction activity retained the ability to associate with N-MLV CA. This points to a second function of the PRYSPRY domain and indicates that CA-binding alone is not sufficient for TRIM5α to block incoming viral particles. It is conceivable that there are regions of intermolecular association involving the PRYSPRY domain that are dispensable for CA binding but important for subsequent restriction activity. For example, the PRYSPRY domain of one TRIM5α monomer might interact with RING or B-box domains of another TRIM5α monomer.

Prior to this study, it was proposed that the PRYSPRY domain possesses two independent binding surfaces and that it functions as an adaptor molecule that mediates interaction between two different proteins (49). The proposed interaction surface A corresponds to the putative CA-binding surface of TRIM5α and the site of several PYRIN/TRIM20 mutants that cause familial Mediterranean fever. Interaction surface B corresponds to the site of other PYRIN/TRIM20 mutants that cause familial Mediterranean fever and MID1/TRIM18 mutants that cause Opitz syndrome. Interestingly, if the structural model proposed here is correct, interaction surface B also corresponds to a hot spot where the mutants that disrupt TRIM5α restriction activity reported here are clustered. Taken together with the large body of disease-causing mutations, the data here suggest that an unknown factor associates with the TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain at the hot spot for mutants that disrupt restriction activity, that the binding surface for this putative factor is independent of the surface that binds to CA, and that this factor is essential for retroviral restriction activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lionel Berthoux, Oliver Billker, Steve Goff, Vincent Racaniello, Claudio Realini, Saul Silverstein, and Madeleine Zufferey for reagents, technical assistance, and generosity.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1AI36199 and Swiss National Science Foundation grant 3100A0-113558 to J.L. and Swiss National Science Foundation grant 3100A0-102218 to M.G.G. S.S. was supported by NIH training grant T32AI007161.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 January 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alber, T. 1989. Mutational effects on protein stability. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 58765-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 253389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass, S. H., M. G. Mulkerrin, and J. A. Wells. 1991. A systematic mutational analysis of hormone-binding determinants in the human growth hormone receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 884498-4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett, W. F., N. F. Paoni, B. A. Keyt, D. Botstein, A. J. Jones, L. Presta, F. M. Wurm, and M. J. Zoller. 1991. High resolution analysis of functional determinants on human tissue-type plasminogen activator. J. Biol. Chem. 2665191-5201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger, B., D. B. Wilson, E. Wolf, T. Tonchev, M. Milla, and P. S. Kim. 1995. Predicting coiled coils by use of pairwise residue correlations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 928259-8263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berthoux, L., S. Sebastian, D. M. Sayah, and J. Luban. 2005. Disruption of human TRIM5α antiviral activity by nonhuman primate orthologues. J. Virol. 797883-7888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bock, M., K. N. Bishop, G. Towers, and J. P. Stoye. 2000. Use of a transient assay for studying the genetic determinants of Fv1 restriction. J. Virol. 747422-7430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowerman, B., P. O. Brown, J. M. Bishop, and H. E. Varmus. 1989. A nucleoprotein complex mediates the integration of retroviral DNA. Genes Dev. 3469-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Combet, C., C. Blanchet, C. Geourjon, and G. Deleage. 2000. NPS@: network protein sequence analysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowan, S., T. Hatziioannou, T. Cunningham, M. A. Muesing, H. G. Gottlinger, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2002. Cellular inhibitors with Fv1-like activity restrict human and simian immunodeficiency virus tropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9911914-11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham, B. C., and J. A. Wells. 1989. High-resolution epitope mapping of hGH-receptor interactions by alanine-scanning mutagenesis. Science 2441081-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dao-Pin, S., D. E. Anderson, W. A. Baase, F. W. Dahlquist, and B. W. Matthews. 1991. Structural and thermodynamic consequences of burying a charged residue within the hydrophobic core of T4 lysozyme. Biochemistry 3011521-11529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fassati, A., and S. P. Goff. 1999. Characterization of intracellular reverse transcription complexes of Moloney murine leukemia virus. J. Virol. 738919-8925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grutter, C., C. Briand, G. Capitani, P. R. Mittl, S. Papin, J. Tschopp, and M. G. Grutter. 2006. Structure of the PRYSPRY-domain: implications for autoinflammatory diseases. FEBS Lett. 58099-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatziioannou, T., D. Perez-Caballero, A. Yang, S. Cowan, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2004. Retrovirus resistance factors Ref1 and Lv1 are species-specific variants of TRIM5α. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10110774-10779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James, L. C., A. H. Keeble, Z. Khan, D. A. Rhodes, and J. Trowsdale. 2007. Structural basis for PRYSPRY-mediated tripartite motif (TRIM) protein function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1046200-6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Javanbakht, H., W. Yuan, D. F. Yeung, B. Song, F. Diaz-Griffero, Y. Li, X. Li, M. Stremlau, and J. Sodroski. 2006. Characterization of TRIM5α trimerization and its contribution to human immunodeficiency virus capsid binding. Virology 353234-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keckesova, Z., L. M. Ylinen, and G. J. Towers. 2004. The human and African green monkey TRIM5α genes encode Ref1 and Lv1 retroviral restriction factor activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10110780-10785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleywegt, G. J., and T. A. Jones. 1998. Databases in protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 541119-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laskowski, R. A., J. A. Rullmannn, M. W. MacArthur, R. Kaptein, and J. M. Thornton. 1996. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, Y., X. Li, M. Stremlau, M. Lee, and J. Sodroski. 2006. Removal of arginine 332 allows human TRIM5α to bind human immunodeficiency virus capsids and to restrict infection. J. Virol. 806738-6744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mische, C. C., H. Javanbakht, B. Song, F. Diaz-Griffero, M. Stremlau, B. Strack, Z. Si, and J. Sodroski. 2005. Retroviral restriction factor TRIM5α is a trimer. J. Virol. 7914446-14450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitrophanous, K., S. Yoon, J. Rohll, D. Patil, F. Wilkes, V. Kim, S. Kingsman, A. Kingsman, and N. Mazarakis. 1999. Stable gene transfer to the nervous system using a non-primate lentiviral vector. Gene Ther. 61808-1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakayama, E. E., H. Miyoshi, Y. Nagai, and T. Shioda. 2005. A specific region of 37 amino acid residues in the SPRY (B30.2) domain of African green monkey TRIM5α determines species-specific restriction of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac infection. J. Virol. 798870-8877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naviaux, R. K., E. Costanzi, M. Haas, and I. M. Verma. 1996. The pCL vector system: rapid production of helper-free, high-titer, recombinant retroviruses. J. Virol. 705701-5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohkura, S., M. W. Yap, T. Sheldon, and J. P. Stoye. 2006. All three variable regions of the TRIM5α B30.2 domain can contribute to the specificity of retrovirus restriction. J. Virol. 808554-8565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez-Caballero, D., T. Hatziioannou, A. Yang, S. Cowan, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2005. Human tripartite motif 5α domains responsible for retrovirus restriction activity and specificity. J. Virol. 798969-8978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez-Caballero, D., T. Hatziioannou, F. Zhang, S. Cowan, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2005. Restriction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by TRIM-CypA occurs with rapid kinetics and independently of cytoplasmic bodies, ubiquitin, and proteasome activity. J. Virol. 7915567-15572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perron, M. J., M. Stremlau, M. Lee, H. Javanbakht, B. Song, and J. Sodroski. 2007. The human TRIM5α restriction factor mediates accelerated uncoating of the N-tropic murine leukemia virus capsid. J. Virol. 812138-2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perron, M. J., M. Stremlau, and J. Sodroski. 2006. Two surface-exposed elements of the B30.2/SPRY domain as potency determinants of N-tropic murine leukemia virus restriction by human TRIM5α. J. Virol. 805631-5636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perron, M. J., M. Stremlau, B. Song, W. Ulm, R. C. Mulligan, and J. Sodroski. 2004. TRIM5α mediates the postentry block to N-tropic murine leukemia viruses in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10111827-11832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reymond, A., G. Meroni, A. Fantozzi, G. Merla, S. Cairo, L. Luzi, D. Riganelli, E. Zanaria, S. Messali, S. Cainarca, A. Guffanti, S. Minucci, P. G. Pelicci, and A. Ballabio. 2001. The tripartite motif family identifies cell compartments. EMBO J. 202140-2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sebastian, S., and J. Luban. 2005. TRIM5α selectively binds a restriction-sensitive retroviral capsid. Retrovirology 240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sebastian, S., E. Sokolskaja, and J. Luban. 2006. Arsenic counteracts human immunodeficiency virus type 1 restriction by various TRIM5 orthologues in a cell type-dependent manner. J. Virol. 802051-2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sokolskaja, E., L. Berthoux, and J. Luban. 2006. Cyclophilin A and TRIM5α independently regulate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity in human cells. J. Virol. 802855-2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song, B., F. Diaz-Griffero, H. Park Do, T. Rogers, M. Stremlau, and J. Sodroski. 2005. TRIM5α association with cytoplasmic bodies is not required for antiretroviral activity. Virology 343201-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song, B., B. Gold, C. O'Huigin, H. Javanbakht, X. Li, M. Stremlau, C. Winkler, M. Dean, and J. Sodroski. 2005. The B30.2(SPRY) domain of the retroviral restriction factor TRIM5α exhibits lineage-specific length and sequence variation in primates. J. Virol. 796111-6121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song, B., H. Javanbakht, M. Perron, D. H. Park, M. Stremlau, and J. Sodroski. 2005. Retrovirus restriction by TRIM5α variants from Old World and New World primates. J. Virol. 793930-3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stremlau, M., C. M. Owens, M. J. Perron, M. Kiessling, P. Autissier, and J. Sodroski. 2004. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5α restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature 427848-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stremlau, M., M. Perron, M. Lee, Y. Li, B. Song, H. Javanbakht, F. Diaz-Griffero, D. J. Anderson, W. I. Sundquist, and J. Sodroski. 2006. Specific recognition and accelerated uncoating of retroviral capsids by the TRIM5α restriction factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1035514-5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stremlau, M., M. Perron, S. Welikala, and J. Sodroski. 2005. Species-specific variation in the B30.2(SPRY) domain of TRIM5α determines the potency of human immunodeficiency virus restriction. J. Virol. 793139-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 254876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 224673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Towers, G., M. Collins, and Y. Takeuchi. 2002. Abrogation of Ref1 retrovirus restriction in human cells. J. Virol. 762548-2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Towers, G. J., T. Hatziioannou, S. Cowan, S. P. Goff, J. Luban, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2003. Cyclophilin A modulates the sensitivity of HIV-1 to host restriction factors. Nat. Med. 91138-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Parijs, L., Y. Refaeli, J. D. Lord, B. H. Nelson, A. K. Abbas, and D. Baltimore. 1999. Uncoupling IL-2 signals that regulate T cell proliferation, survival, and Fas-mediated activation-induced cell death. Immunity 11281-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welker, R., H. Hohenberg, U. Tessmer, C. Huckhagel, and H. G. Krausslich. 2000. Biochemical and structural analysis of isolated mature cores of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 741168-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wertman, K. F., D. G. Drubin, and D. Botstein. 1992. Systematic mutational analysis of the yeast ACT1 gene. Genetics 132337-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woo, J. S., J. H. Imm, C. K. Min, K. J. Kim, S. S. Cha, and B. H. Oh. 2006. Structural and functional insights into the B30.2/SPRY domain. EMBO J. 251353-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yap, M. W., S. Nisole, C. Lynch, and J. P. Stoye. 2004. Trim5α protein restricts both HIV-1 and murine leukemia virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10110786-10791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yap, M. W., S. Nisole, and J. P. Stoye. 2005. A single amino acid change in the SPRY domain of human Trim5α leads to HIV-1 restriction. Curr. Biol. 1573-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yee, J. K., A. Miyanohara, P. LaPorte, K. Bouic, J. C. Burns, and T. Friedmann. 1994. A general method for the generation of high-titer, pantropic retroviral vectors: highly efficient infection of primary hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 919564-9568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang, F., T. Hatziioannou, D. Perez-Caballero, D. Derse, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2006. Antiretroviral potential of human tripartite motif-5 and related proteins. Virology 353396-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]