Abstract

Regulated trafficking of AMPA receptors (AMPARs) is an important mechanism that underlies the activity-dependent modification of synaptic strength. Trafficking of AMPARs is regulated by specific interactions of their subunits with other proteins. Recently, we have reported that the AMPAR subunit GluR1 binds the cGMP-dependent kinase type II (cGKII) adjacent to the kinase catalytic site, and that this interaction is increased by cGMP. In this complex, cGKII phosphorylates GluR1 at serine 845 (S845), a site known to be phosphorylated also by PKA. S845 phosphorylation leads to an increase of GluR1 on the plasma membrane. In neurons, cGMP is produced by soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), which is activated by nitric oxide (NO). Calcium flux through the NMDA receptor (NMDAR) activates neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), which produces NO. Using a combination of biochemical and electrophysiological experiments, we have shown that trafficking of GluR1 is under the regulation of NO, cGMP and cGKII. Moreover, our study indicates that the interaction of cGKII with GluR1, which is under the regulation of the NMDAR and NO, plays an important role in hippocampal plasticity.

AMPARs are hetero-tetrameric cation channels comprised of a combinatorial assembly of four subunits, GluR1-GluR4 (GluRA-D)1. Delivery of AMPARs to the postsynaptic membrane leads to long-term potentiation (LTP), whereas removal of these receptors leads to long-term depression (LTD) 2–4. Both of these forms of synaptic plasticity are influenced by NMDAR activity 5, 6. Extensive evidence suggests that GluR1 has an important role in LTP 7–9. The molecular mechanisms that regulate GluR1 synaptic delivery during LTP are complex, and involve interactions of the GluR1 C-terminal domain (CTD) with scaffolding proteins 10, 11, and a series of phosphorylation steps at several Ser residues on the GluR1 CTD 12. Phosphorylation of one of these sites in the GluR1 CTD by PKA, S845, was shown to be required, although not sufficient, for GluR1 synaptic insertion during LTP 13.

Although the role of GluR1 and other proteins in LTP has been established, the specific signaling pathways involved are still not understood. One molecule believed to play an important role in LTP is NO 14–18. NO is a diffusible second messenger that is produced at synapses at postsynaptic sites 19 and can pass through lipid membranes. Perhaps because of its capacity to diffuse across the plasma membrane, particular attention has been given to mechanisms in which NO exerts a retrograde action and controls presynaptic function 17, 20–22. However, previous studies have suggested that both NO and its downstream molecules sGC, cGMP and cGKs may play a role in the postsynaptic as well as presynaptic neurons during potentiation 23–27. While appearance of new release sites and increase of release probability of pre-existing release sites are known to occur within the presynaptic terminal following activation of the NO cascade during potentiation 28, a specific pathway for NO control of the activity-dependent trafficking of GluR1, which has been demonstrated to be an essential component of LTP, has not been reported.

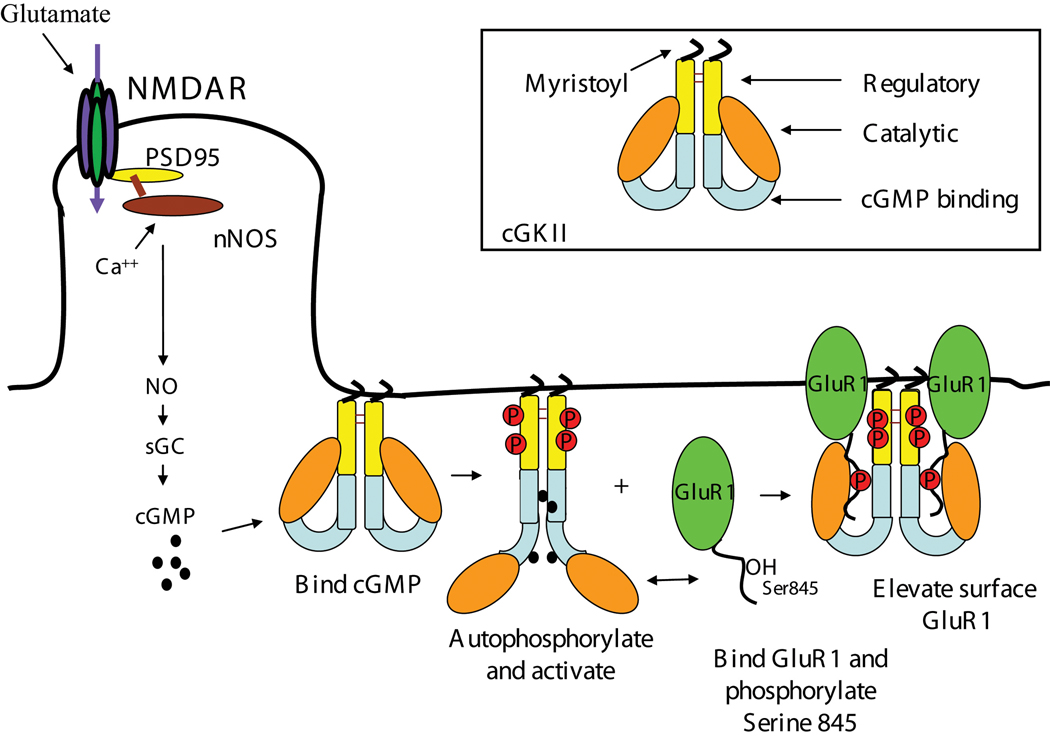

Activation of sGC by NO induces the formation of cGMP, and one cGMP target is the cGKs. There are two cGK isoforms, cGKI and cGKII. While cGKI is cytosolic and in the brain is preferentially enriched in the cerebellum, cGKII is located in cellular membranes and is widely distributed in the brain 29. In our recent study we report that NMDAR stimulation leads to cGKII binding to GluR1, dependent on nNOS activity and cGMP production 30. In the absence of cGMP, the catalytic site of cGKII binds the autoinhibitory (AI) domain of the kinase, keeping the kinase inactive (Figure 1). Activation of cGKII by cGMP induces a conformational change in cGKII that causes autophosphorylation of its autoinhibitory (AI) domain, decreasing the affinity of the AI domain for the catalytic domain 31. This releases the AI domain and leads to a larger conformational change of the kinase, in which the catalytic domain no longer binds the AI domain. Using in vitro mutagenesis, we determined that the region in GluR1 that binds cGKII structurally and functionally mimics the cGKII AI domain. We found that autophosphorylated cGKII interacts with GluR1, and this interaction facilitates phosphorylation of GluR1 S845. In cultured hippocampal neurons, activation of cGKII induces an accumulation of GluR1 on the cellular plasma membrane at extrasynaptic sites, and blockage of cGKII activity prevents the surface increase of GluR1, and also the increase in mEPSC frequency and amplitude, that follows a chemical form of LTP (chemLTP).

Figure 1.

Model for the regulation of GluR1 trafficking by cGKII. The proposed sequence of events that occur after NMDAR stimulation is shown. Based on the membrane location of the kinase and the fact that GluR1 surface levels are increased after S845 phosphorylation, the kinase is depicted at the plasma membrane and the receptor intracellularly, before S845 phosphorylation. However, the subcellular locations of the kinase and the receptor at the time of phosphorylation have not yet been established. The inset shows the schematic of the structure of cGKII and its different protein domains. The regulatory domain of the kinase contains the AI domain.

We specifically tested the role of the cGKII-GluR1 interaction in the cGMP-dependent GluR1 trafficking by expressing a cGKII dominant negative inhibitor peptide in both hippocampal cultured neurons and the hippocampal slice. Expression of this peptide in cultured hippocampal neurons blocks the increase of GluR1 surface expression, and prevents the increase in amplitude and frequency of mEPSCs, after chemLTP. Addtionally, expression of this inhibitor peptide in the hippocampal slice caused a reduction in CA1 LTP evoked by a tetanus.

These data provide evidence of a specific pathway for the NMDAR control of S845 phosphorylation leading to LTP. This pathway is particularly significant because it relies on NO, long known to contribute to synaptic plasticity 16, 32. The convergence of both the PKA and cGKII pathways on S845 phosphorylation underscores the importance of this phosphorylation step for GluR1 insertion into the plasma membrane and later into the the synapse. It is possible that both pathways will control GluR1 trafficking under different circumstances. Interestingly, LTP induced by three-train tetanization in the CA1 region of hippocampus is inhibited by cGK blockers 25, whereas it is affected to a lesser extent when induced by four-train tetanization. On the other hand, it was shown that PKA contributes more to four-train LTP than to three-train LTP, suggesting that both PKA and cGK are involved in LTP induced by multiple trains of tetanic stimulation, but that the contribution of cGK declines as that of PKA grows with increasing numbers of tetani 25. These results suggest that cGK and PKA play somewhat complementary roles during LTP. The exact step, exocytosis or endocytosis, that is controlled by S845 phosphorylation, is not established, but it is likely to be the same when either PKA or cGKII phosphorylates S845.

References

- 1.Hollmann M, Heinemann S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry MF, Ziff EB. Receptor trafficking and the plasticity of excitatory synapses. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:279–286. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malinow R, Malenka RC. AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song I, Huganir RL. Regulation of AMPA receptors during synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:578–588. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44:5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi Y, Shi SH, Esteban JA, Piccini A, Poncer JC, Malinow R. Driving AMPA receptors into synapses by LTP and CaMKII: requirement for GluR1 and PDZ domain interaction. Science. 2000;287:2262–2267. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamanillo D, Sprengel R, Hvalby O, Jensen V, Burnashev N, Rozov A, Kaiser KM, Koster HJ, Borchardt T, Worley P, Lubke J, Frotscher M, Kelly PH, Sommer B, Andersen P, Seeburg PH, Sakmann B. Importance of AMPA receptors for hippocampal synaptic plasticity but not for spatial learning. Science. 1999;284:1805–1811. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HK, Takamiya K, Han JS, Man H, Kim CH, Rumbaugh G, Yu S, Ding L, He C, Petralia RS, Wenthold RJ, Gallagher M, Huganir RL. Phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit is required for synaptic plasticity and retention of spatial memory. Cell. 2003;112:631–643. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leonard AS, Davare MA, Horne MC, Garner CC, Hell JW. SAP97 is associated with the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptor GluR1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19518–19524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen L, Liang F, Walensky LD, Huganir RL. Regulation of AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit surface expression by a 4. 1N-linked actin cytoskeletal association. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7932–7940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07932.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehm J, Malinow R. AMPA receptor phosphorylation during synaptic plasticity. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1354–1356. doi: 10.1042/BST0331354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esteban JA, Shi SH, Wilson C, Nuriya M, Huganir RL, Malinow R. PKA phosphorylation of AMPA receptor subunits controls synaptic trafficking underlying plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:136–143. doi: 10.1038/nn997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhuo M, Small SA, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Nitric oxide and carbon monoxide produce activity-dependent long-term synaptic enhancement in hippocampus. Science. 1993;260:1946–1950. doi: 10.1126/science.8100368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Dell TJ, Huang PL, Dawson TM, Dinerman JL, Snyder SH, Kandel ER, Fishman MC. Endothelial NOS and the blockade of LTP by NOS inhibitors in mice lacking neuronal NOS. Science. 1994;265:542–546. doi: 10.1126/science.7518615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haley JE, Wilcox GL, Chapman PF. The role of nitric oxide in hippocampal long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1992;8:211–216. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90288-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuman EM, Madison DV. A requirement for the intercellular messenger nitric oxide in long-term potentiation. Science. 1991;254:1503–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.1720572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bon C, Bohme GA, Doble A, Stutzmann JM, Blanchard JC. A Role for Nitric Oxide in Long-term Potentiation. Eur J Neurosci. 1992;4:420–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garthwaite J, Boulton CL. Nitric oxide signaling in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:683–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arancio O, Kiebler M, Lee CJ, Lev-Ram V, Tsien RY, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Nitric oxide acts directly in the presynaptic neuron to produce long-term potentiation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Cell. 1996;87:1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81797-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Dell TJ, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER, Arancio O. Tests of the roles of two diffusible substances in long-term potentiation: evidence for nitric oxide as a possible early retrograde messenger. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:11285–11289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohme GA, Bon C, Stutzmann JM, Doble A, Blanchard JC. Possible involvement of nitric oxide in long-term potentiation. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;199:379–381. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90505-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Son H, Lu YF, Zhuo M, Arancio O, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. The specific role of cGMP in hippocampal LTP. Learn Mem. 1998;5:231–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arancio O, Antonova I, Gambaryan S, Lohmann SM, Wood JS, Lawrence DS, Hawkins RD. Presynaptic role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase during long-lasting potentiation. J Neurosci. 2001;21:143–149. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00143.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu YF, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Nitric oxide signaling contributes to late-phase LTP and CREB phosphorylation in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10250–10261. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10250.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu YF, Hawkins RD. Ryanodine receptors contribute to cGMP-induced late-phase LTP and CREB phosphorylation in the hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1270–1278. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang HG, Lu FM, Jin I, Udo H, Kandel ER, de Vente J, Walter U, Lohmann SM, Hawkins RD, Antonova I. Presynaptic and postsynaptic roles of NO, cGK, and RhoA in long-lasting potentiation and aggregation of synaptic proteins. Neuron. 2005;45:389–403. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ninan I, Liu S, Rabinowitz D, Arancio O. Early presynaptic changes during plasticity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Embo J. 2006;25:4361–4371. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francis SH, Corbin JD. Cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases: intracellular receptors for cAMP and cGMP action. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1999;36:275–328. doi: 10.1080/10408369991239213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serulle Y, Zhang S, Ninan I, Puzzo D, McCarthy M, Khatri L, Arancio O, Ziff EB. A GluR1-cGKII interaction regulates AMPA receptor trafficking. Neuron. 2007;56:670–688. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wall ME, Francis SH, Corbin JD, Grimes K, Richie-Jannetta R, Kotera J, Macdonald BA, Gibson RR, Trewhella J. Mechanisms associated with cGMP binding and activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2380–2385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0534892100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bon CL, Garthwaite J. On the role of nitric oxide in hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1941–1948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01941.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]