Abstract

As part of a larger project to improve information transfer within public health settings, we studied the information workflow associated with communicable disease (CD) activities in a local health department. As part of that study we examined a newly adopted online system used for reporting CD data to the state department of public health. An information workflow analysis was performed using the ethnographic methods of interviews and observations. In addition to providing a detailed description of the context of CD reporting activities in a local health department, our study uncovered a mismatch between the newly piloted electronic reporting system and the CD work as enacted by health department personnel.

Introduction

Communicable disease investigation and reporting is a key function of local health departments. In an effort to increase the efficiency of communicable disease (CD) reporting activities, electronic reporting systems are being developed and implemented across the U.S. For example, Washington State recently implemented an electronic reporting system to collect, manage, and report data collected from CD investigation from local health departments to the state. The system is called the Public Health Issue Management System (PHIMS). The goal of PHIMS was to allow local health departments to report CDs via the Internet in a standardized format during the course of CD investigations, thereby streamlining the process. However, little is known about the effect of CD reporting systems such as PHIMS on health department efficiency and workflow.

Experience over the last ten years has shown that the costs of designing information systems without a clear understanding of user values, needs, and practices is very high and may result in failed systems, inefficient work, and inability to use data1. The premature adoption of hospital computerized physician order entry systems, for instance, has taught us that computerized systems that fail to take into consideration the values and actual working processes of users may have unintended consequences that are costly and unsafe2,3,4. Systematic qualitative evaluation of workflow processes has been used in clinical practice and research to improve the design of information systems 5,6,7,8 however, similar studies have not been reported for public health practice.

We set out to gain a richer understanding of public health CD activities through the use of ethnographic techniques. An unanticipated discovery of this ethnographic inquiry was the uncovering of problems with the adoption of the newly implemented reporting system, PHIMS, developed by the state health department to improve the efficiency of local health department reporting to the state.

Methods

We undertook a workflow analysis to better understand the goals, values, processes, and tasks associated with CD work. We used a suite of ethnographic data collection and qualitative data analysis methods in this study. We used ethnographic methods because they provide rich detail regarding the context and values behind the work being done. Because the findings to be reported here regarding the use of PHIMS emerged from the overall investigation, we describe the methods employed and the data analysis process for the full study.

Data Collection

The qualitative data collection methods of interviews, observations, and focus groups were employed over a six-month period to investigate CD workflow. The research team consisted of three people with experience in conducting qualitative research: a public health informatician, a usability expert, and a biomedical informatics graduate student. The University of Washington Human Subjects Division approved the study protocol and informed consent was obtained from all participants for interviews, observations, and focus groups.

Interviews with public health professionals on staff at the Kitsap County Health District (KCHD) were conducted over a six-month period in the fall of 2006. KCHD is a medium sized health department (124 employees) located in the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State. The health department serves a county of ~250,000 people. KCHD employees are involved with CD reporting in all phases from the initial notification of the local health department to reporting the case to the state. Because CD activities crossed several programs, health department staffs were interviewed from all programs involving CDs that require case reporting, including programs for sexually transmitted diseases, AIDS/HIV, and Environmental Health (EH). CD nurses, social workers, epidemiologists, switchboard operators, EH specialists and administrators were interviewed.

During the hour-long onsite interviews, participants described the tasks involved in CD reporting: data collection, modes of data transfer, forms used, information resources, and people involved in carrying out CD work. Interviews were recorded and a semi-structured interview protocol was used. Investigators took field notes and collected artifacts (i.e. forms and guidelines) used in carrying out work activities. Ethnographic observation sessions were linked to the interviews. Further, because of the diversity of activities they were involved in, their pivotal roles in the CD work processes, and the complexity of their workflow, two key informants (the primary CD nurse and the main switchboard operator) were selected for additional half-day work-shadow observations. Field notes, photographs, and recordings were collected during the observations and were included in the analysis.

After the first rounds of iterative preliminary data analysis were completed (see below), a draft workflow representation was constructed. In a two-hour focus group, informants, other public health personnel, and the director of the local public health agency reviewed the draft, validated its general accuracy, and suggested refinements that were included in the final data analysis.

Data Analysis

The nine interviews and the focus group yielded 462 pages of transcripts. Data analysis was conducted in two main phases. First, the transcripts and observation notes were analyzed by three trained analysts using content analysis9. After reviewing the transcripts, a coding scheme was developed based on the identification of common themes through a constant comparative method10. Attributes of the workflow, including triggers of action, actors, modes of information transfer, tasks, values, and barriers, were identified and used to develop an initial visual model of CD workflow. We iteratively analyzed the data and refined the workflow model. Questions requiring clarification were noted by researchers and investigated further in the focus group. A final flow diagram was then developed.

The following discussion now turns specifically to the issues surrounding the use of PHIMS and the problems of mapping the design of this public health IS to the work as actually enacted by the personnel in the local public health agency.

Results

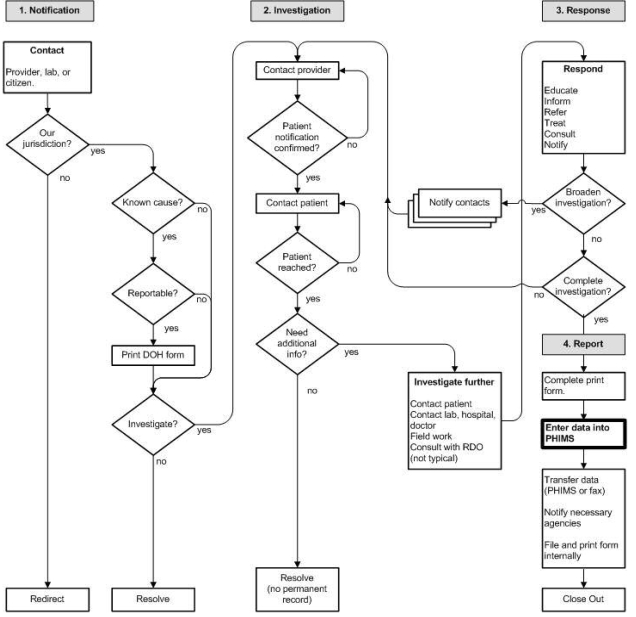

Figure 1 below summarizes the final task analysis for the four main CD reporting workflow processes. We first summarize the four main workflow processes involved in the overall work and then characterize the work from the perspective of the public health staff.

Figure 1.

Communicable Disease Investigation Workflow

Summarizing the four main workflow processes

Four main CD workflow processes were identified: notification, investigation, response, and reporting. Notification refers to the processes followed when the health department is informed by community providers, hospitals and laboratories of the occurrence of a “notifiable condition” (a disease considered of public health significance, that must by law be reported). In the process of investigation, the CD nurse gathers details of the case including the timing of symptoms, potential contacts, lab results, and the circumstances leading to occurrence of the notifiable condition. The response phase of the investigation often takes place closely tied to the investigation and involves educating the patient(s) about disease management or other public-health concerns, referral of the patient to the appropriate health-care provider, and ensuring appropriate treatment of the patient. Reporting consists of sending the results of the case investigation to the state department of health for aggregation and analysis.

Characterizing the CD work from the perspective of those who do it

Ethnographic methods were useful at uncovering the underlying characteristics of the work processes being followed and the work-related values held by those doing the work. In CD work, the focus of the staff is on investigation and response, not reporting.

Also, CD work is mobile; information collection is distributed, discontinuous and episodic. Finally, reporting occurs only after investigation and response are completed.

It is useful to look more closely at these three characteristics of CD work.

1. Focus on investigation and response, not reporting: The primary focus of local health department CD nurses is on the processes of investigation and response. Reporting to the state, which is what the PHIMS system was designed to facilitate, is at most a peripheral concern. As the health department director put it:

“We are not so focused on that it is ‘notifiable’, as we are focused on what public health action needs to take place now. Yes, counting the numbers is important at the end of the day, but the goal is to prevent further outbreaks.”

2. Communicable disease work is mobile; information collection is distributed, discontinuous and episodic: Investigators prefer to carry the printout version of the form with them into the field during investigations, where notations are made in the margins as the investigation unfolds. The form is physically handed off as nurses cover for each other. As one informant described the situation:

“Having something to at least write notes on is good, because it does take sometimes several hours and sometimes even days to get back to the case.”

The realities of the work context defeat the original expectation that data would be entered directly into PHIMS during the course of the investigation. Because the work is mobile, the CD investigator is frequently collecting data when away from her computer. For example, one informant described a typical workday as follows:

“There was an outbreak of chickenpox at the jail. I left the jail in the morning with the PCR in hand and delivered it to the State lab. I was going to go back, but I got hung up on a bat exposure at the camp. So I ended up staying at the lab most of the day, on the phone.”

To further reduce the likelihood that PHIMS could be used as the designers envisioned, the system requires that data elements be entered in a specified order and it is necessary to save every field before moving on to the next one. In contrast, the investigators, respecting the way that their informants want to tell their stories, need to be able to capture information in the form and order in which the story is communicated to them. During phone interviews, the information gathered from the patient will not follow the order of the fields in PHIMS. Also the PHIMS fields are difficult to scroll through while talking on the phone, as explained by one CD investigator:

“I wish I could [enter data directly into PHIMS], but when you’re interviewing you don’t interview in line. If I was just typing that wouldn’t be a problem, but I would be scrolling up and down these pages trying to find where to put the fact that he lives on a farm.”

3. Reporting occurs only after the investigation and response are completed: In the view of those doing the work, reporting is secondary and peripheral. As one investigator explained, before the introduction of PHIMS, the investigators would fax the form to the state immediately upon completion of the case.

Because of the extra time now required for data entry, however, reporting to the state via PHIMS is often delayed until the investigator has a span of time available, which may be several days after the case has been completed.

Workflow and PHIMS

The point at which PHIMS plays a role in the workflow is highlighted in bold. We show the entire process to underline the small, marginal role of reporting in the overall workflow. Note that the only use of PHIMS is, at the very end of the process, to report the CD occurrence to the state.

Before the introduction of PHIMS, the state had created forms with fields for all of data that the state requires public health agencies to report about each communicable disease; these forms are now available online in downloadable form. Routine practice before the introduction of PHIMS was to download and print the form, collect the data over time, and then at the end of the process, fax the form to the state.

Although the system designers initially envisioned that, after the introduction of PHIMS, the data would be entered during the course of the investigation, the CD nurses continue to use a hardcopy of the form during the investigation. Then, at the end of the process, they enter data into PHIMS in the required fields online using the marked-up hardcopy as the data source. The persistent usage of the printed forms can be understood by examining the work from the perspective of the CD nurses actually doing it.

Discussion

Although the PHIMS system was initially developed as an investigation management system to facilitate the investigation and reporting process, we saw that it was not being utilized as intended. Instead of being integrated into the CD workflow, we observed only one point of contact with the PHIMS system in the whole process: at the very end, in reporting the case to the state. In addition, the reporting procedure is slow and tedium is high.

It appears that the underlying cause for this mismatch between the intentions of the designers and the behaviors of the users arises from two sources. The first is a fundamental misunderstanding of the procedural constraints imposed by the work context. Because the work is mobile and unpredictable, it is awkward and inefficient to enter the data during the investigation process, as the designers had intended.

The second source of the mismatch is a mistaken assumption about the priorities and motivations of the system users. The CD investigators put the highest value on investigation and resolution of public health problems; the reporting was very much after the fact, and was extra work imposed on them at the very moment that they were ready to move on to the next investigation. The state epidemiologists, who aggregate and analyze the data, are the primary users of the data. Because the people entering the data are not the primary users of the aggregated reported data, the task of data entry was not highly meaningful to them. Therefore, the reward for using the system is minimal, because the users of the system are not the users of the information collected.

Limitations: This case study of a single health department is not necessarily generalizable to other health departments. Studies are currently underway to compare CD workflow with other health departments in Washington State.

Conclusion and Considerations for Future Designers

We have presented a detailed discussion of an information system that is poorly integrated into the work as it is done. The failure is not just procedural but has to do with a mismatch between the values and goals of the users and the values and goals of the system developers. Based on our findings, we make the following recommendations:

Developers of CD information systems should consider how to incorporate reporting activities more integrally into the work as enacted and consider incorporating support for key processes in the investigation and response phases.

Because communicable disease work is mobile, designers should consider mobile technologies for the system platform or key component.

Because information collection is distributed, discontinuous and episodic, information systems designed for CD investigation should allow for note-taking, temporary files, and other support for developing emergent information.

We have used ethnographic methods to identify areas of mismatch between a CD information system and the work it is designed to facilitate. Such mismatches have been demonstrated to affect the adoption of information systems in clinical care 5,6. However, this is the first time it has been investigated and reported in a public health practice setting. A contextual understanding of the characteristics and values associated with CD workflow allowed us to provide recommendations regarding information system design. Our hope is that these considerations will improve the design and utilization of future information systems developed for public health practice.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the employees of the Kitsap County Health District for participating in this study. This work was supported by the CDC Centers of Excellence grant no. 1P01CD000261-01 and the NLM Biomedical and Health Informatics training grant no. 5T15LM007442.

References

- 1.Kirah AC, Fuson C, Grudin J, Feldman E. “Ethnography for Software Development.”. In: Bias R, Mayhew D, editors. Cost Justifying Usability: An Update for the Internet Age”. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2005. pp. 415–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ash J. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11:104–12. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darbyshire P. ‘Rage against the machine?’: nurses’ and midwives’ experiences of using Computerized Patient Information Systems for clinical information. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:17–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wears RL, Berg M. “Computer technology and clinical work: still waiting for Godot.”. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1261–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ash JS, Gorman PN, Lavelle M, Payne TH, Massaro TA, Frantz GL, Lyman JA. A cross-site qualitative study of physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(2):188–200. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng CH, Goldstein MK, Geller E, Levitt RE. The effects of CPOE on ICU workflow: an observational study. Proc AMIA Symp. 2003:150–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unertl KM, Weinger MB. Modeling workflow and information flow in chronic disease care. Proc AMIA Symp. 2007:1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson CD, Zeiger RF, Amar KD, Goldstein MK. Task analysis of writing hospital admission orders: Evidence of a problem-based approach. Proc AMIA Symp. 2006:389–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patton MQ.2002. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods 3rd ed.

- 10.Glaser BG. The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative Analysis. Social Problem. 1965;12(4):436–45. [Google Scholar]