Abstract

We have developed a reliable genetic selection strategy for isolating interacting proteins based on the “hitchhiker” mechanism of the Escherichia coli twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway. This method, designated FLI-TRAP (functional ligand-binding identification by Tat-based recognition of associating proteins), is based on the unique ability of the Tat system to efficiently cotranslocate noncovalent complexes of 2 folded polypeptides. In the FLI-TRAP assay, the protein to be screened for interactions is engineered with an N-terminal Tat signal peptide, whereas the known or putative partner protein is fused to mature TEM-1 β-lactamase (Bla). Using a series of c-Jun and c-Fos leucine zipper (JunLZ and FosLZ) variants of known affinities, we observed that only those chimeras that expressed well and interacted strongly in the cytoplasm were able to colocalize Bla into the periplasm and confer β-lactam antibiotic resistance to cells. Likewise, the assay was able to efficiently detect interactions between intracellular single-chain Fv (scFv) antibodies and their cognate antigens. The utility of FLI-TRAP was then demonstrated through random library selections of amino acid substitutions that restored (i) heterodimerization to a noninteracting FosLZ variant, and (ii) antigen binding to a low-affinity scFv antibody. Because Tat substrates must be correctly folded before transport, FLI-TRAP favors the identification of soluble, nonaggregating, protease-resistant protein pairs and, thus, provides a powerful tool for routine selection of interacting partners (e.g., antibody-antigen), without the need for purification or immobilization of the binding target.

Keywords: ligand binding proteins, protein folding quality control, signal peptide, twin-arginine translocation, 2-hybrid system

Protein–protein interactions are key molecular events that integrate multiple gene products into functional complexes in virtually every cellular process. Because such interactions mediate numerous disease states and biological mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of bacterial and viral infections, identification of protein–protein interactions remains one of the most important challenges in the postgenomics era. The yeast 2-hybrid (Y2H) system (1) has been the tool of choice for revealing numerous protein–protein interactions, underlying diverse protein networks and complex protein machinery inside living cells. To date, Y2H has been used to generate protein interaction maps for humans (2), Drosophila melanogaster (3), Caenorhabditis elegans (4), Saccharomyces cerivisiae (5, 6), vaccinia virus (7), and Escherichia coli bacteriophage T7 (8). Another important application of the Y2H methodology is the discovery of diagnostic and therapeutic proteins, whose mode of action is high-affinity binding to a target peptide or protein. For example, several groups have isolated antibody fragments that are readily expressed in the cytoplasm of cells where they bind specifically to a desired target (9, 10), and in certain instances ablate protein function (11, 12).

Although the 2H system was initially developed by using yeast as a host organism, numerous bacterial (B)2H systems are now common laboratory tools and represent an experimental alternative with certain advantages over the yeast-based systems (13, 14). A number of these bacterial approaches employ split activator/repressor proteins; thus, they are functionally analogous to the GAL4-based yeast system (15–17). Unfortunately, both Y2H and B2H GAL4-type assays are prone to a high frequency of false positives that arise from spurious transcriptional activation (18), and complicate the interpretation of interaction data. As proof, a comparative assessment revealed that >50% of the data generated using Y2H were likely to be false positives (19). To address this shortcoming, several groups have exploited oligomerization-assisted reassembly of split enzymes such as adenylate cyclase (20), β-lactamase (Bla) (21), and dihydrofolate reductase (22, 23), as well as split fluorescent proteins (24, 25). Alternatively, a number of methodologies for detecting interacting proteins in bacteria have been developed that do not rely on interaction-induced complementation of protein fragments, but instead use phage display (26), FRET (27), and cytolocalization of GFP (28).

In this study, we have developed a genetic selection for protein–protein interactions in E. coli based on the native ability of the twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway to both proofread (29–31) and colocalize (32) folded protein complexes across biological membranes. In the latter instance, Wu and coworkers (32) revealed that the Tat pathway exports heterodimers whereby only 1 protein subunit carries an N-terminal Tat signal peptide (ssTorA), a process referred to as “hitchhiker” export. More recently, we exploited this natural hitchhiker mechanism for the periplasmic expression of a murine FAB antibody fragment (30). In this earlier study, an ssTorA was fused to the FAB heavy chain, whereas the FAB light chain was expressed without any signal peptide. After coexpression of the individual heavy and light chains in E. coli, the FAB subunits assembled in the cytoplasm and were colocalized to the periplasm via the Tat machinery. Along similar lines, a genetic reporter of protein–protein interactions using the Tat system was described recently by Strauch and Georgiou (33); however, the assay relied on complex phenotypic complementation that potentially limits the effectiveness of the approach. Here, we show that Tat-mediated colocalization of the reporter enzyme Bla enabled semiquantitative, high-throughput selection of a wide range of interacting polypeptide pairs that were stably expressed, and interacted with high affinity in the bacterial cytoplasm. By using this method, termed FLI-TRAP (functional ligand-binding identification by Tat-based recognition of associating proteins), we were able to efficiently isolate high-affinity binding proteins from large combinatorial libraries after just a single round of mutagenesis and selection.

Results

Reconstitution of the Tat-Dependent Hitchhiker Mechanism for a Native Tat Substrate.

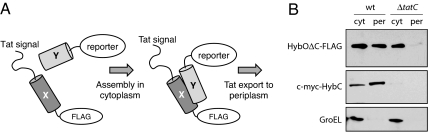

To verify whether the Tat hitchhiker mechanism could be developed as a general platform for detecting intracellular protein–protein interactions (Fig. 1A), we first attempted to reconstitute the natural hitchhiker mechanism that underlies export of the heterodimeric E. coli hydrogenase-2 (HYD2) complex using affinity tagged components expressed from multicopy expression plasmids. A plasmid was created encoding the HYD2 large subunit HybO with its native C-terminal inner membrane anchor replaced with a FLAG affinity tag (DYKDDDDK) yielding HybOΔC-FLAG. Removal of the C-terminal anchor from HybO renders the HybOC complex soluble in the periplasmic fraction, but does not interfere with Tat transport (34), and was performed here to ease immunoblot analysis. A second plasmid was created, which encoded the HYD2 small subunit, HybC, carrying an N-terminal c-myc epitope tag (EQKLISEEDL). When these 2 constructs were coexpressed in WT MC4100 cells, both FLAG and c-myc cross-reactive bands were observed in the periplasmic fraction (Fig. 1B). This finding was consistent with the earlier observation that HybC, which lacks a discernable export signal, is efficiently escorted into the periplasm by its HybO partner (32). As expected, no detectable export of either HybOΔC-FLAG or c-myc-HybC was observed when these 2 constructs were coexpressed in the ΔtatC mutant strain BMI1 (Fig. 1B; see ref. 35). Interestingly, c-myc-HybC was notably absent from both the cytoplasmic and periplasmic fractions of ΔtatC cells, consistent with reports that some nonexported Tat substrates are efficiently degraded by an unidentified “housecleaning” mechanism (30, 36). Importantly, these results confirm that hitchhiker export can be functionally reconstituted using multicopy expression plasmids.

Fig. 1.

Tat-mediated hitchhiker export in bacteria. (A) Schematic representation of engineered assay for cotranslocation of interacting pairs via the Tat pathway. The Tat signal peptide chosen was ssTorA, the reporter was either the c-myc epitope tag or Bla, and X and Y were interacting domains or entire proteins. (B) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic (cyt) and periplasmic (per) fractions from cells coexpressing HybOΔC and c-myc-HybC, where each was detected by using an anti-FLAG and anti-c-myc antibody, respectively. The cytoplasmic chaperone GroEL was detected by using an anti-GroEL antibody and served as a fractionation marker.

Folding Quality Control Governs Hitchhiker Transport of PhoA via the Tat System.

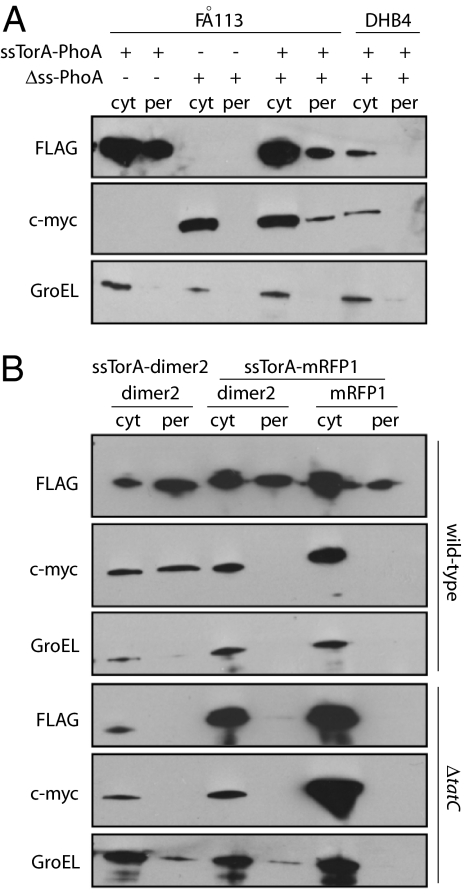

To test whether the Tat folding quality control mechanism remained intact during hitchhiker transport, we used Tat-targeted PhoA (ssTorA-PhoA), because the folding of this construct can be toggled by using strains of E. coli that either favor or disfavor disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm (30). Our earlier studies showed that correctly folded (i.e., oxidized) ssTorA-PhoA is transported via the Tat system, whereas incorrectly folded (i.e., reduced) ssTorA-PhoA is incapable of Tat-specific export (30). It is well known that oxidized, enzymatically active PhoA forms a structural homodimer (37). However, it was not clear from our earlier studies whether the Tat machinery exports folded PhoA monomers that assemble into dimers in the periplasm or, instead, exports the assembled homodimeric PhoA complex. We created 2 expression plasmids similar to those used in the HybO-HybC experiments above: the first encoded a variant of PhoA with its native Sec signal replaced with the Tat-specific signal peptide from E. coli trimethylamine N-oxide reductase (ssTorA) and a C-terminal FLAG tag, and the second encoded a signalless version of PhoA (ΔssPhoA) with a C-terminal c-myc epitope tag. Expression of ΔssPhoA-c-myc alone in E. coli strain FÅ113, which permits disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm (38), resulted exclusively in cytoplasmic accumulation (Fig. 2A). Coexpression of ΔssPhoA-c-myc along with ssTorA-PhoA-FLAG in FÅ113 cells resulted in accumulation of both the FLAG-tagged and c-myc-tagged versions of PhoA in the periplasm (Fig. 2A), providing evidence for the export of a ssTorA-PhoA-FLAG::ΔssPhoA-c-myc heterodimer. In contrast, when the same constructs were coexpressed in the parental WT strain DHB4, where the reducing state of the cytoplasm is sufficient to prevent disulfide bond formation, neither was exported (Fig. 2A). These data demonstrate that the folding quality control mechanism is active during Tat-mediated hitchhiker transport, and that the Tat machinery can transport large dimeric complexes that have assembled prior to translocation.

Fig. 2.

Hitchhiker cotranslocation of synthetic Tat substrates. Western blot analysis of cyt and per fractions from cells coexpressing (A) ssTorA-PhoA-FLAG and ΔssPhoA-c-myc or (B) ssTorA-dimer2-FLAG, ssTorA-mRFP1-FLAG, dimer2-c-myc, and mRFP1-c-myc as indicated. Detection of each was performed by using an anti-FLAG or anti-c-myc antibodies as indicated. GroEL was used to indicate the quality of fractionations and was detected with an anti-GroEL antibody.

Homodimeric Eukaryotic Proteins Exhibit Cotranslocation Behavior.

To test whether the Tat hitchhiker mechanism could be extended to nonbacterial proteins, we next assayed the export of an engineered variant of Discosoma DsRed named dimer2 that forms stable dimers in the E. coli cytoplasm (39). As expected, coexpression of ssTorA-dimer2-FLAG along with dimer2-c-myc resulted in colocalization of the dimer2-c-myc protein into the periplasm (Fig. 2B). Controls using ΔtatC cells confirmed that the cotranslocation of dimer2-c-myc by virtue of its association with ssTorA-dimer2-FLAG depended on the Tat system (Fig. 2B). Cotranslocation was also highly specific for the dimer2-dimer2 interaction, because a monomeric derivative of dimer2, mRFP1 (39) cloned as an ssTorA-mRFP1-FLAG chimera, did not colocalize dimer2-c-myc or mRFP1-c-myc even though ssTorA-mRFP1-FLAG was itself efficiently exported via the Tat system (Fig. 2B).

Conversion of the Hitchhiker Mechanism into a Genetic Selection.

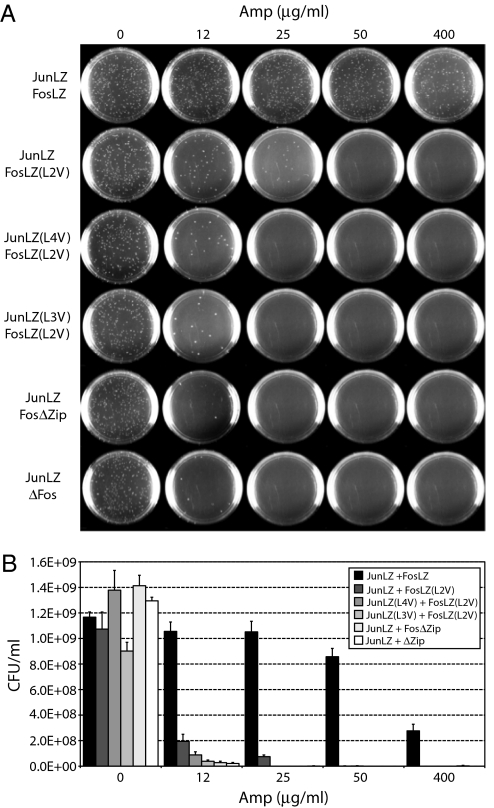

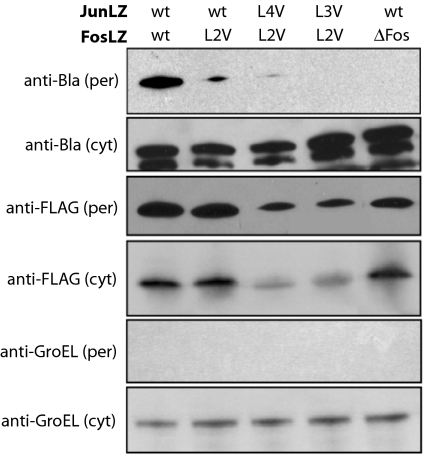

To develop a general platform that would allow rapid isolation of protein–protein interactions while minimizing false positive results, a selection strategy termed FLI-TRAP was created (Fig. 1A). FLI-TRAP entails one plasmid, encoding an ssTorA-X-FLAG chimera, and a second, encoding a Y-reporter fusion protein, where the reporter in this context is Bla, and X and Y are any 2 interacting proteins. We hypothesized that the interaction of X and Y would produce a physical linkage between ssTorA and Bla, resulting in Tat-dependent colocalization of Bla into the periplasm. In previous studies, we found that Bla was an exceptional reporter for Tat-dependent export and allowed facile selection of soluble proteins using growth medium containing ampicillin (Amp) (31). In this same study, we demonstrated that Bla tolerates fusion to a wide array of structurally diverse proteins at its N terminus. To validate the FLI-TRAP selection, we chose the basic region-leucine zipper (bZIP) domains of c-Jun (JunLZ) and c-Fos (FosLZ) as the X and Y components, respectively. Coexpression and interaction of ssTorA-JunLZ-FLAG and FosLZ-Bla was sufficient to colocalize FosLZ-Bla to the periplasm and confer an MIC of 25 μg/mL Amp to WT MC4100 cells [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1a]. On the contrary, expression of the same constructs in ΔtatC mutant cells conferred no detectable growth on selective medium (Fig. S1a), confirming that detection of this interaction depended on the Tat pathway. We suspected that the relatively low MIC in the case of WT cells was due to inefficient Tat export, which can often be alleviated by increasing the copy number of the TatABC proteins (40). Indeed, increased expression of TatABC from plasmid pBR-TatABC resulted in an MIC of >400 μg/mL Amp for WT cells coexpressing ssTorA-JunLZ-FLAG and FosLZ-Bla (Fig. 3 A and B), which represented a 16-fold increase of the MIC, compared with cells expressing native levels of TatABC. Also, the Amp resistance of WT cells coincided with the appearance of strong bands in the periplasmic fraction for both ssTorA-JunLZ-FLAG and FosLZ-Bla (Fig. 4). Thus, TatABC coexpression was used for all selection experiments hereafter.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypic selection of interacting protein pairs. (A) Selective plating of WT cells carrying pBR-TatABC and coexpressing ssTorA-JunLZ-FLAG and FosLZ-Bla or derivatives thereof. Overnight cultures were diluted 105-fold in liquid LB and plated on LB agar supplemented with Amp at the concentrations indicated to determine the MIC for each JunLZ-FosLZ pair. (B) Number of colony forming units per mL (CFU/mL) recovered on 0–400 μg/mL Amp. Values reported represent the average of 3 replicate experiments, and error bars represent the SE of the mean.

Fig. 4.

Cotranslocation of Bla chimeras to the periplasm. Western blot analysis of per and cyt fractions generated from WT cells carrying pBR-TatABC and coexpressing ssTorA-JunLZ-FLAG and FosLZ-Bla or derivatives thereof as indicated. Detection of ssTorA-JunLZ-FLAG constructs was with anti-FLAG antibody and detection of FosLZ-Bla was with anti-Bla antibody. GroEL was detected by using an anti-GroEL antibody and served as a fractionation marker.

Next, we constructed JunLZ and FosLZ variants, where leucine residues in the d position of the bZIP domain heptad repeat were mutated to valine; such substitutions have been reported to decrease binding affinity and dimerization stability (41, 42). Coexpression of ssTorA-JunLZ-FLAG and the FosLZ(L2V)-Bla variant, where leucine in the second heptad of FosLZ was substituted with valine, conferred resistance to WT cells up to 25 μg/mL Amp (Fig. 3 A and B), which was ≈16 times lower than the resistance conferred by the WT JunLZ/FosLZ interaction. Western blot analysis revealed a concomitant decrease in the quantity of the FosLZ(L2V)-Bla fusion that was colocalized to the periplasm of these cells (Fig. 4). The smaller degradation product seen in the cytoplasmic fractions likely represents proteolytic fragments in which the Fos domain has been removed and, thus, the resulting fragment is not colocalized to the periplasm. Interestingly, the amount of ssTorA-JunLZ-FLAG in the periplasm was nearly identical in these experiments, suggesting that the relative amount of each Bla fusion colocalized in the periplasm correlates positively with the relative binding affinity. When FosLZ(L2V)-Bla was coexpressed with ssTorA-JunLZ-FLAG variants carrying leucine mutations in the third or fourth heptad of the JunLZ motif, WT cells were susceptible to Amp concentrations as low as 12 μg/mL Amp (Fig. 3 A and B), and virtually no Bla was detected in the periplasm (Fig. 4). Thus, weakened affinity and/or reduced expression levels of each fusion resulted in deficient Bla transport and sensitivity to very low levels of Amp under the conditions tested. Identical results were observed for negative controls, including an LZ deletion that prevents Jun-Fos dimerization (FosΔZip-Bla) (25), and a version of Bla expressed without the N-terminal FosLZ sequence (ΔFos-Bla).

To determine whether larger complexes of interacting proteins could be accommodated by the Tat system, we next appended the JunLZ domain onto the N terminus of one of the following soluble scaffold proteins: GFP, GST, or thioredoxin-1 (TrxA). When JunLZ was N-terminally displayed on GFP, GST, or TrxA, it remained competent for dimerization with FosLZ-Bla as evidenced by the ability of each to confer an Amp resistant phenotype to WT cells and colocalize FosLZ-Bla to the periplasm (Fig. S1 b and d). Similar colocalization of FosLZ-Bla was observed when the JunLZ domain was moved to the C terminus of GFP (Fig. S1 c and d). Whereas each of these fusions conferred an MIC of ≈25–100 μg/mL Amp when coexpressed with FosLZ-Bla, WT cells coexpressing each fusion with the noninteracting FosΔZip-Bla construct were sensitive to as little as 12 μg/mL Amp. These results provide evidence that complexes as large as ≈80–85 kDa were compatible with FLI-TRAP.

Efficient Selection of Dimerization-Competent FosLZ Variants.

We next validated the suitability of the FLI-TRAP system for performing genetic selections. This validation was accomplished by (i) randomizing the d position of the second heptad of FosLZ by using a PCR strategy with degenerate (NNK) primers and FosLZ(L2V)-Bla as template, and (ii) selecting for FosLZ variants that conferred resistance to WT cells on 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL Amp. Previous mutational analysis revealed that although the canonical leucine is the preferred residue in the d position of the LZ motif, other hydrophobic amino acids are tolerated in this position (16, 43). Consistent with these earlier findings, we found that mutated derivatives isolated across all Amp concentrations showed an extremely strong bias (89%) toward hydrophobic and/or nonpolar residues in the d position with the majority of these residues being either leucine (44%) or methionine (17%) (Table S1). It should be noted that valine and isoleucine were never selected at these Amp concentrations, which was in agreement with our observation that FosLZ(L2V)-Bla was unable to confer resistance beyond 25 μg/mL Amp. A small fraction (11%) of the variants were hydrophilic and/or polar, which was consistent with earlier reports (16, 43), and the helix-breaking residues proline and glycine were never isolated. Interestingly, at 100 μg/mL of Amp, a fairly even distribution of hydrophobic substitutions was recovered; however, as the selection pressure was increased to 200 and 400 μg/mL, leucine became heavily favored (>50%) relative to all other substitutions. Thus, substitution with hydrophobic residues was apparently more favorable as the stringency of selection increased. Consistent with this notion, we observed that cysteine, histidine, and lysine were only selected on 100 μg/mL Amp, whereas tyrosine was not isolated at this concentration, but became rather frequent (15% and 13%) at 200 and 400 μg/mL Amp, respectively.

Selection of Single-Chain (sc) Fv Antibodies that Bind Target Antigens.

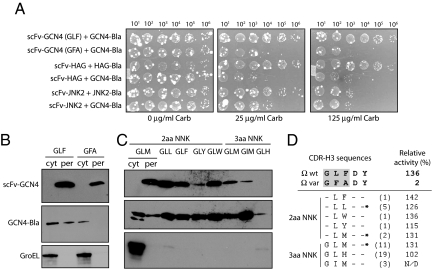

To determine whether FLI-TRAP could be used to select for interactions between larger proteins, we chose several scFv antibodies that were previously developed for stable intracellular expression. These scFvs included anti-GCN4 scFv (Ω-graft variant) that binds the 47-residue bZIP domain of the yeast transcription factor Gcn4 (9), anti-HAG scFv that binds to a peptide of 6 residues from the hamagglutinin protein of influenza virus (44) and anti-JNK2 scFv that is specific for the 48.2-kDa c-Jun N-terminal kinase-2 (JNK2) protein (45). Each of these scFvs was cloned into the “X” position of the FLI-TRAP system and coexpressed with the corresponding antigen-Bla fusion. Carbenicllin (Carb) was used because it gave more reproducible results over the longer times (≈48 h) needed to observe cell growth. In all cases, intracellular interaction between the scFv and the target antigen conferred a clear growth advantage to cells under selective conditions, compared with the control cases where nonspecific antigen-Bla fusions were coexpressed (Fig. 5A, shown for anti-HAG and anti-JNK2 scFvs). Detection of the JNK2/anti-JNK2 system is particularly noteworthy, because this result clearly demonstrates the ability of the FLI-TRAP assay to colocalize an assembled complex of 2 globular proteins that, together with the Bla reporter enzyme, constitute an estimated molecular mass of ≈106 kDa. For the Gcn4/anti-GCN4 case, we used a variant of the Gcn4 bZIP domain called GCN4(7P14P), which contains 2 helix-breaking proline mutations that disrupt the helical structure of the zipper and prevent its coiled-coil-mediated homodimerization (46). Thus, this mutant simplifies the selection process because antigen-antibody binding does not have to compete with the homodimerization process. It was found that only the WT scFv containing the residues GLF in the complementarity-determining region 3 of the heavy chain (CDR-H3) and not a low-affinity anti-GCN4 GFA variant (9) was able to efficiently colocalize GCN4(7P14P)-Bla antigen to the periplasm (Fig. 5B) and confer a significant growth advantage to cells (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Selection of scFv antibodies that bind target antigens. (A) Selective plating of serially diluted cells expressing different antigen-antibody pairs on Carb as indicated. Each spot corresponds to 5 μL of serially diluted cells. (B) Western blot analysis of per and cyt fractions generated from WT cells carrying pBR-TatABC and coexpressing either ssTorA-scFv-GCN4(GLF)-FLAG or ssTorA-scFv-GCN4(GFA)-FLAG with GCN4-Bla. Detection of scFv constructs was with anti-FLAG antibody, and detection of GCN4-Bla was with anti-Bla antibody. GroEL was detected by using an anti-GroEL antibody and served as a fractionation marker. (C) Same as in B for samples generated from cells expressing different ssTorA-scFv-GCN4-FLAG variants as indicated. All samples are per fractions except for the GLM variant, for which both cyt and per fractions are shown. (D) Summary of CDR-H3 library selections including the 5-residue CDR-H3 sequences for the Ω graft WT scFv (GLFDY) and the low-affinity Ω graft variant (GFADY), the latter of which served as the parental clone for library construction. The residues in the shaded box were subjected to NNK randomization (LF in the 2-aa library and GLF in the 3-aa library). Listed are the clones isolated from the 2- and 3-aa NNK library selections. Values in parenthesis indicate the number of times each clone was isolated; clone GLM was isolated from both libraries. Asterisks indicate clones that were isolated multiple times but with different codon usage. Relative activity values are for intracellular binding activity of each clone as reported previously by Plückthun and coworkers (9). ND, not determined.

We next tested whether the FLI-TRAP approach might be exploited to directly isolate antigen-binding scFvs by screening a library of randomized CDR-H3 sequences. To construct a library, we used the low-affinity anti-GCN4 GFA variant as scaffold, in which 2 (FA; 2-aa NNK) or 3 (GFA, 3-aa NNK) amino acids of the CDR-H3 were randomized. The libraries were subjected to 1 round of selection to determine whether the WT, as well as similar or entirely new CDR-H3 sequences that bind the bZIP domain of Gcn4 in vivo, could be isolated by using our system. A total of 1.6 × 106 2-aa NNK clones and 2.6 × 106 3-aa NNK clones were screened on selective plates containing 125 μg/mL Carb, and, 2 days later, ≈1,600 and 150 colonies appeared for the 2- and 3-aa NNK libraries, respectively. A total of 10 positive clones from the 2-aa NNK library and 35 from the 3aa NNK library were picked randomly, and the library plasmids were isolated and retransformed into the same reporter strain to confirm the growth phenotype; 96% (43/45) of these clones conferred a growth advantage to WT cells expressing the GCN4(7P14P)-Bla fusion. Sequencing of the CDR-H3 regions of the 43 positive clones revealed 9 unique DNA sequences encoding 7 unique amino acid sequences (Fig. 5D), all of which were able to colocalize GCN4(7P14P)-Bla to the periplasm of WT cells (Fig. 5C). The sequencing results indicated that (i) several clones were found more than once, and (ii) several variants showed different codon usage. For example, clone GLL was found 5 times in the 2-aa NNK library selection and was encoded by GGA TTG CTG (3×) or GAA CTT CTG (2×). It is noteworthy that one of our isolated clones (variant GIM) is a novel CDR-H3 sequence. All of the other clones isolated in our selection were uncovered previously by Plückthun and coworkers (9), and correspond to scFvs that exhibited the highest binding activity in their in vivo assay (Fig. 5D). On the contrary, clones that exhibited ≈2- to 3-fold less binding activity, compared with the WT CDR-H3 (GLF) in this earlier study (e.g., GLV, GVL, and GLQ), were never isolated during our library selections. Likewise, the CDR-H3 variant containing the amino acid composition GFA, which was the parental clone used in our library construction and was previously found to be ≈75-fold less active than the WT CDR-H3 (9), was also never isolated. Interestingly, even when the first position of the CDR-H3 was varied in our 3-aa NNK library, the resulting clones all contained glycine in this position. This finding is entirely consistent with the observations that the CDR-H3 glycine is part of a 2-residue β-hairpin structure (9) and glycines are highly conserved in this structural motif for steric reasons (47). In summary, these results clearly demonstrate the feasibility of the FLI-TRAP assay to select for antigen-specific single-chain antibodies that fold and function in the intracellular environment.

Discussion

In this study, we have engineered a facile genetic selection for protein–protein interactions in bacteria based on the hitchhiker and folding quality control mechanisms of the Tat export system. We unequivocally established that the Tat hitchhiker export process can be extended to a wide range of synthetic substrates comprising interacting partners of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic origin that assemble into complexes as large as ≈106 kDa. An advantage of FLI-TRAP is that, unlike the Y2H and B2H systems, it does not rely on DNA binding; thus, it is not susceptible to spurious transcriptional activation. Another advantage of this approach is that the tendency of the Tat system to export globular, soluble proteins that do not possess exposed hydrophobic segments (30, 31, 48, 49) provides a built-in safeguard against false positives arising from the interaction of misfolded proteins (misfolded complexes will be blocked for Tat-dependent transport). Because the assay requires the interacting pair to remain associated during membrane transport, it stands to reason that relatively weak interactions (KD ≥1 μM) will not be selected. Indeed, we show that, under selective conditions, our assay readily discriminated between cells expressing native protein pairs of high affinity (KD ≈1 nm) and those that interacted weakly (KD ≈1 μM). For example, selection of JunLZ-FosLZ interactions was most efficient for the WT pair, where the measured KD of dimerization is 0.99 ± 0.30 nM (50). Although KD values for the single leucine variants tested here have not been determined, the dissociation constant of a weakly interacting JunLZ point mutant (V36E) was found to be significantly weaker (0.90 ± 0.13 μM) (50). Likewise, the KD values for the WT GLF and GLW variant of the anti-GCN4 scFv, both clones that were isolated in our library selection, were determined to be 0.35 and 0.6 nM, respectively (9). An ALF variant having ≈1.5-fold less in vivo activity exhibited a 2- to 3-fold greater KD of 1.1 nM (9). Thus, we estimate that the GFA clone tested here, which did not confer growth in our assay and gave an in vivo activity that was nearly 75-fold weaker than the WT GLF clone (9), has a KD on the order of ≈0.1 μM. Collectively, these results suggest that the FLI-TRAP method favors selection of very stable protein interactions and, as a result, could effectively eliminate false positives that have limited other cell-based protein–protein interaction assays (18, 19). Also, the observation that higher affinity complexes (native JunLZ-FosLZ versus JunLZ-FosL2V) conferred increased resistance to bacterial cells under selective conditions implies that the FLI-TRAP strategy could be used to affinity mature binding proteins simply by plating on increasing antibiotic concentrations.

It is noteworthy that the phenotypic output of FLI-TRAP was not always attributable to affinity alone. Rather, in several instances, it appeared that a decrease in the level of 1 or both of the expressed protein chimeras (as a result of, for example, decreased solubility, increased aggregation, or increased proteolysis) was responsible for the decrease in cotranslocation of Bla and/or MIC on Amp. Thus, we conclude that differences in Bla transport and resistance conferred to bacterial cells are likely to reflect both the strength of association between the interacting proteins as well as their intracellular stability (e.g., solubility, protease sensitivity, etc.). For many applications, the fact that FLI-TRAP selects for interacting protein pairs that are stably expressed and remain soluble after their expression in vivo should prove advantageous. Another advantage of the FLI-TRAP assay is that the hydrolysis of Amp by Bla is a straightforward biological activity and, in every case tested so far, not inhibited by the accompanying heterodimeric complex. In a recent report by Strauch and Georgiou (33), a similar Tat-mediated system for protein–protein interactions was developed using the disulfide oxidase DsbA or maltose-binding protein (MBP) as a reporter. The drawback of these reporters is the complexity of the phenotype that underlies the screen/selection. For example, in the case of MBP, after formation of an ssTorA-X::Y-MBP complex, MBP must bind maltose and then deliver it to the MalFGK(2) inner membrane complex. The intricacy of this reporter activity may prove problematic, especially considering that, in certain instances, direct fusions to MBP (e.g., ssTorA-GFP-MBP) are incapable of performing this function even when the fusion protein is correctly localized to the periplasm and the fusion partner (e.g., GFP) is active (52). It should also be pointed out that even though previous reports suggest Bla is undesirable as a reporter because low-level resistance to Amp has been observed with Bla lacking a signal peptide (33, 51), in our hands, we never observed nonspecific leakage of Bla to the periplasm (Fig. 3A, ΔFos-Bla). Also, in practice, we do not anticipate this Bla leakage to be a problem, because the inclusion of a nonexported protein or protein domain at the N terminus of Bla appears to be sufficient to prevent the leakage that was observed earlier (51). Last, because FLI-TRAP was shown to be useful for random library selection of amino acid substitutions that restored (i) heterodimerization to a noninteracting FosLZ variant, and (ii) antigen binding to a low-affinity scFv antibody, we believe this method should provide a powerful complement to existing protein display methods (e.g., phage and ribosome display) for addressing fundamental questions of protein structure and molecular recognition, and for evolving high-affinity binding proteins from antibody and nonantibody scaffolds.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions.

Wild-type E. coli strain MC4100 and isogenic ΔtatC derivatives of MC4100, namely B1LK0 (53) or BMI1 (35), were used for all experiments except those involving E. coli PhoA, where strains DHB4, FÅ113, and FUDDY (30, 38) were used instead. For all plasmids used in this study, see Table S2, and for details regarding their construction and the construction of the plasmid libraries, see SI Methods. Typically, E. coli cells were grown in LB medium overnight, subcultured into fresh LB, and then incubated at 30 or 37 °C. Protein synthesis was induced when the cells reached an OD600 ≈0.4–0.5 by adding IPTG and arabinose to a final concentration of 0.1 mM and 0.02–1.0% wt/vol, respectively. Antibiotics were provided at the following concentrations: Amp and Carb, 100 μg/mL; chloramphenicol (Cm), 25 μg/mL; kanamycin (Kan), 50 μg/mL, and tetracycline (Tet), 10 μg/mL.

Selective Growth Assays.

The screening and selection of cells on Amp or Carb was performed essentially as described previously (31). For specific details, see SI Methods.

Protein Analysis.

Cells expressing recombinant proteins were harvested 5–6 h after induction. Subcellular fractionation was performed by using the ice-cold osmotic shock procedure (30, 54). Soluble protein was quantified by the Bio-Rad protein assay, with BSA as standard. Cytoplasmic and periplasmic proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting as previously described (30). The following primary antibodies were used (dilutions in parentheses): mouse anti-FLAG (1:3,000; Stratagene); mouse anti-c-myc clone 9E10 (1:5,000; Sigma); mouse anti-Bla (1:150; Abcam); rabbit anti-GroEL (1:20,000; Sigma). The quality of all fractionations was determined by immunodetection of the cytoplasmic GroEL protein (30).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Adam Fisher and Li Ling Lee for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Career Award CBET-0449080 (to M.P.D.), National Institutes of Health Grant CA132223A (to M.P.D.), New York State Office of Science, Technology and Academic Research James D. Watson Award (to M.P.D.), and a Thai Royal Government Fellowship (D.W.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0704048106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fields S, Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein–protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rual JF, et al. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein–protein interaction network. Nature. 2005;437:1173–1178. doi: 10.1038/nature04209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giot L, et al. A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2003;302:1727–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.1090289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S, et al. A map of the interactome network of the metazoan C elegans. Science. 2004;303:540–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1091403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito T, et al. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4569–4574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uetz P, et al. A comprehensive analysis of protein–protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2000;403:623–627. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCraith S, Holtzman T, Moss B, Fields S. Genome-wide analysis of vaccinia virus protein–protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4879–4884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080078197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartel PL, Roecklein JA, SenGupta D, Fields S. A protein linkage map of Escherichia coli bacteriophage T7. Nat Genet. 1996;12:72–77. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.der Maur AA, et al. Direct in vivo screening of intrabody libraries constructed on a highly stable single-chain framework. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45075–45085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Visintin M, et al. Selection of antibodies for intracellular function using a two-hybrid in vivo system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11723–11728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka T, Rabbitts TH. Intrabodies based on intracellular capture frameworks that bind the RAS protein with high affinity and impair oncogenic transformation. EMBO J. 2003;22:1025–1035. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tse E, et al. Intracellular antibody capture technology: Application to selection of intracellular antibodies recognising the BCR-ABL oncogenic protein. J Mol Biol. 2002;317:85–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu JC, Kornacker MG, Hochschild A. Escherichia coli one- and two-hybrid systems for the analysis and identification of protein–protein interactions. Methods. 2000;20:80–94. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ladant D, Karimova G. Genetic systems for analyzing protein–protein interactions in bacteria. Res Microbiol. 2000;151:711–720. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(00)01136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dove SL, Joung JK, Hochschild A. Activation of prokaryotic transcription through arbitrary protein–protein contacts. Nature. 1997;386:627–630. doi: 10.1038/386627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu JC, O'Shea EK, Kim PS, Sauer RT. Sequence requirements for coiled-coils: Analysis with lambda repressor-GCN4 leucine zipper fusions. Science. 1990;250:1400–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.2147779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joung JK, Ramm EI, Pabo CO. A bacterial two-hybrid selection system for studying protein-DNA and protein–protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7382–7387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110149297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fields S. High-throughput two-hybrid analysis. The promise and the peril. Febs J. 2005;272:5391–5399. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Mering C, et al. Comparative assessment of large-scale data sets of protein–protein interactions. Nature. 2002;417:399–403. doi: 10.1038/nature750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karimova G, Pidoux J, Ullmann A, Ladant D. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5752–5756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wehrman T, et al. Protein–protein interactions monitored in mammalian cells via complementation of beta-lactamase enzyme fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3469–3474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062043699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pelletier JN, Arndt KM, Plückthun A, Michnick SW. An in vivo library-versus-library selection of optimized protein–protein interactions. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:683–690. doi: 10.1038/10897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelletier JN, Campbell-Valois FX, Michnick SW. Oligomerization domain-directed reassembly of active dihydrofolate reductase from rationally designed fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12141–12146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh I, Hamilton AD, Regan L. Antiparallel leucine zipper-directed protein reassembly: Application to the green fluorescent protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5658–5659. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu CD, Chinenov Y, Kerppola TK. Visualization of interactions among bZIP and Rel family proteins in living cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Mol Cell. 2002;9:789–798. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palzkill T, Huang W, Weinstock GM. Mapping protein-ligand interactions using whole genome phage display libraries. Gene. 1998;221:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.You X, et al. Intracellular protein interaction mapping with FRET hybrids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18458–18463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605422103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding Z, et al. A novel cytology-based, two-hybrid screen for bacteria applied to protein–protein interaction studies of a type IV secretion system. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:5572–5582. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.20.5572-5582.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matos CF, Robinson C, Di Cola A. The Tat system proofreads FeS protein substrates and directly initiates the disposal of rejected molecules. EMBO J. 2008;27:2055–2063. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeLisa MP, Tullman D, Georgiou G. Folding quality control in the export of proteins by the bacterial twin-arginine translocation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6115–6120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937838100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher AC, Kim W, DeLisa MP. Genetic selection for protein solubility enabled by the folding quality control feature of the twin-arginine translocation pathway. Protein Sci. 2006;15:449–458. doi: 10.1110/ps.051902606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodrigue A, et al. Co-translocation of a periplasmic enzyme complex by a hitchhiker mechanism through the bacterial tat pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13223–13228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strauch EM, Georgiou G. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on the twin-arginine transporter pathway of E. coli. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1001–1008. doi: 10.1110/ps.062687207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatzixanthis K, Palmer T, Sargent F. A subset of bacterial inner membrane proteins integrated by the twin-arginine translocase. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1377–1390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ize B, Stanley NR, Buchanan G, Palmer T. Role of the Escherichia coli Tat pathway in outer membrane integrity. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1183–1193. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santini CL, et al. Translocation of jellyfish green fluorescent protein via the Tat system of Escherichia coli and change of its periplasmic localization in response to osmotic up-shock. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8159–8164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sone M, Kishigami S, Yoshihisa T, Ito K. Roles of disulfide bonds in bacterial alkaline phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6174–6178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bessette PH, Aslund F, Beckwith J, Georgiou G. Efficient folding of proteins with multiple disulfide bonds in the Escherichia coli cytoplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13703–13708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell RE, et al. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett CM, et al. Quantitative export of a reporter protein, GFP, by the twin-arginine translocation pathway in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00583-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moitra J, Szilak L, Krylov D, Vinson C. Leucine is the most stabilizing aliphatic amino acid in the d position of a dimeric leucine zipper coiled coil. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12567–12573. doi: 10.1021/bi971424h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu BY, Zhou NE, Kay CM, Hodges RS. Packing and hydrophobicity effects on protein folding and stability: Effects of beta-branched amino acids, valine and isoleucine, on the formation and stability of two-stranded alpha-helical coiled coils/leucine zippers. Protein Sci. 1993;2:383–394. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Heeckeren WJ, Sellers JW, Struhl K. Role of the conserved leucines in the leucine zipper dimerization motif of yeast GCN4. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3721–3724. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.14.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jermutus L, et al. Tailoring in vitro evolution for protein affinity or stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:75–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011311398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koch H, Grafe N, Schiess R, Plückthun A. Direct selection of antibodies from complex libraries with the protein fragment complementation assay. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:427–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger C, et al. Antigen recognition by conformational selection. FEBS Lett. 1999;450:149–153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00458-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sibanda BL, Thornton JM. Beta-hairpin families in globular proteins. Nature. 1985;316:170–174. doi: 10.1038/316170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richter S, et al. Functional Tat transport of unstructured, small, hydrophilic proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33257–33264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruser T, Yano T, Brune DC, Daldal F. Membrane targeting of a folded and cofactor-containing protein. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:1211–1221. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heuer KH, et al. Development of a sensitive peptide-based immunoassay: Application to detection of the Jun and Fos oncoproteins. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9069–9075. doi: 10.1021/bi952817o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bowden GA, Baneyx F, Georgiou G. Abnormal fractionation of beta-lactamase in Escherichia coli: Evidence for an interaction with the inner membrane in the absence of a leader peptide. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3407–3410. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3407-3410.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisher AC, et al. Exploration of twin-arginine translocation for the expression and purification of correctly folded proteins in Escherichia coli. Microbial Biotechnol. 2008;1:403–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2008.00041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bogsch EG, et al. An essential component of a novel bacterial protein export system with homologues in plastids and mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18003–18006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sargent F, et al. Overlapping functions of components of a bacterial Sec-independent protein export pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:3640–3650. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.