Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of an educational intervention explaining symptoms to encourage graded exercise in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.

Design

Randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Chronic fatigue clinic and infectious diseases outpatient clinic.

Subjects

148 consecutively referred patients fulfilling Oxford criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome.

Interventions

Patients randomised to the control group received standardised medical care. Patients randomised to intervention received two individual treatment sessions and two telephone follow up calls, supported by a comprehensive educational pack, describing the role of disrupted physiological regulation in fatigue symptoms and encouraging home based graded exercise. The minimum intervention group had no further treatment, but the telephone intervention group received an additional seven follow up calls and the maximum intervention group an additional seven face to face sessions over four months.

Main outcome measure

A score of ⩾25 or an increase of ⩾10 on the SF-36 physical functioning subscale (range 10 to 30) 12 months after randomisation.

Results

21 patients dropped out, mainly from the intervention groups. Intention to treat analysis showed 79 (69%) of patients in the intervention groups achieved a satisfactory outcome in physical functioning compared with two (6%) of controls, who received standardised medical care (P<0.0001). Similar improvements were observed in fatigue, sleep, disability, and mood. No significant differences were found between the three intervention groups.

Conclusions

Treatment incorporating evidence based physiological explanations for symptoms was effective in encouraging self managed graded exercise. This resulted in substantial improvement compared with standardised medical care.

Introduction

Patients' beliefs are based on evidence they find convincing.1 As most of the symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome are physical, patients develop a strong physical perception of the condition. In the absence of medical explanation, many attribute intense and unpleasant symptoms to an underlying disease and are disinclined to accept that psychological factors may have a role. Attributing symptoms to ongoing physical disease is an important predictor of poor prognosis.2

The aetiology of chronic fatigue syndrome is controversial, and extensive research has failed to identify any serious underlying pathology. However, many patients show signs of disrupted physiological regulation. Chronic fatigue syndrome may be associated with desynchronisation of circadian rhythms, which may be a consequence of disruption of the daily cues needed to reset the biological clock—for example, by a viral infection or stressful life events.3 Evidence of sleep abnormalities4 and cortisol deficiency5,6 are consistent with this hypothesis. The subsequent reduction in activity results in cardiovascular and muscular deconditioning, which exacerbates symptoms.7,8 Inaccurate illness beliefs that encourage avoidance of activity and chaotic sleep patterns may perpetuate the condition.9 This model suggests that providing patients with evidence based illness beliefs may facilitate activity and bring about therapeutic change.

Two randomised clinical trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and graded exercise that are compatible with this model have produced positive results.10,11 However, cognitive behaviour therapy is expensive and carries the risk of deterring patients who are fearful of contact with mental health workers. We have developed a treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome that is briefer. It involves educating patients about the medical evidence of the physical and psychological effects of physical deconditioning and circadian dysrhythmia, with the intention of encouraging a self managed graded exercise programme. A more detailed account of the intervention approach, adapted to the needs of non-ambulatory patients, has been published.12

Participants and methods

Patients were initially recruited from consecutive referrals to a dedicated chronic fatigue clinic at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital. Because the clinic closed recruitment continued from an infectious diseases outpatient clinic at University Hospital, Aintree. All patients aged 15-55 were assessed by a consultant physician (RHTE or FJN) to confirm the diagnosis.

Inclusion criteria specified that patients fulfilled the Oxford criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome13 and scored <25 on the physical functioning subscale of the SF-36 questionnaire.14 This subscale has a range of 10 to 30, where 10 indicates maximum physical limitation in self care and 30 indicates ability to do vigorous sports. Patients were excluded if they were having further physical investigations or taking other treatments, including antidepressants (unless the same dose had been taken for at least three months without improvement); had a psychotic illness, somatisation disorder, eating disorder, or history of substance misuse; or were confined to a wheelchair or bed.

We calculated that we needed a sample size of 26 patients per group using pilot data and assuming a 20% difference between groups and a power of 80% at the 5% significance level. We set a recruitment target of 34 patients per group to allow for drop outs. The study was approved by the district research ethics committee, and all participants gave written informed consent.

Randomisation

Immediately after medical assessment, eligible patients were randomised into four groups by means of a sequence of computer generated random numbers in sealed numbered envelopes. We used a simple randomisation with stratification for scores on the hospital anxiety and depression scale,15 using a cut off of 11 to indicate clinical depression.

Treatment conditions

Patients in the control group received standardised medical care. This comprised a medical assessment, advice, and an information booklet that encouraged graded activity and positive thinking but gave no explanations for the symptoms. Patients were advised that they would be sent a questionnaire to assess their progress at three, six, and 12 months and discharged back to primary care.

The intervention groups all received a medical assessment followed by evidence based explanations of symptoms that encouraged graded activity. Explanation of symptoms focused on circadian dysrhythmia, physical deconditioning, and sleep abnormalities. A graded exercise programme was designed in collaboration with each patient and tailored to his or her functional abilities. Once patients were successfully engaged in treatment, the role of predisposing and perpetuating psychosocial factors was discussed. Treatment was supported by an educational information pack that reiterated the verbal explanations. Patients were advised that they would be sent questionnaires for assessment at three, six, and 12 months. The intervention groups differed in the method and number of treatment sessions.

Minimum intervention group—Patients received two face to face sessions totalling three hours in which symptoms were explained and the graded exercise programme was designed.

Telephone intervention group—In addition to the minimum intervention patients received seven planned telephone contacts, each of about 30 minutes over three months. During these calls explanations for symptoms and the treatment rationale were reiterated and problems associated with graded exercise were discussed with the use of motivational interviewing techniques.16

Maximum intervention group—In addition to the minimum intervention, patients received seven one hour face to face treatment sessions over three months. These had the same function as the telephone sessions in the telephone intervention group.

All patients in the intervention groups were told that they would be telephoned after the three and six month assessments to review progress. In addition, they could request additional telephone advice by leaving a message on an answering machine. Table 1 shows the mean number and duration of telephone calls made to patients in the intervention groups. Calls requested by patients were mainly for support and reassurance.

Table 1.

Mean number and duration of telephone calls to patients in active intervention treatment groups

| Treatment group | Mean No of telephone calls* | Mean duration of telephone calls |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum intervention | 3.56 | 18.5 minutes |

| Telephone intervention | 9.22 | 29.4 minutes |

| Maximum intervention | 4.52 | 18.4 minutes |

Includes the two planned calls to review progress at three and six months in the minimum and maximum intervention groups and the seven planned calls in the telephone intervention group.

Outcome measures

Patients were sent questionnaires containing validated measures of outcome by post before randomisation and at three, six, and 12 months. Primary outcomes were scores on the physical functioning subscale of the SF-36 questionnaire and on the fatigue scale (range 0-11, scores >3 indicate excessive fatigue).17 The predetermined criterion for clinically important improvement at one year was a score of ⩾25 or more or an increase of ⩾10 from baseline on the physical functioning scale (range 10 to 30). This is similar to normal daily functioning for the UK general population.18 At baseline the mean score for physical functioning was 16.0.

Secondary outcome measures included scores on the hospital anxiety and depression scales (scores >10 indicate caseness),15 a four item sleep problem questionnaire,19 and a seven point global impression of change score one year after trial entry (ranging from “very much better” to “very much worse”).20 A simple questionnaire was used to assess illness beliefs and experience of treatment at one year.

Statistical analysis

We used an intention to treat analysis. For patients who dropped out of treatment, the last values obtained were carried forward. Complete data were obtained for all patients who completed treatment except for three: two did not complete the questionnaire at three months and one did not complete the questionnaire at one year.

We tested the significance of changes in primary outcomes by analysing scores at one year with baseline scores and depression scores as covariates; this strategy reduced the problems associated with multiple testing. Group comparisons were not prespecified and were subjected to Bonferroni testing, which is highly conservative. The clinical importance of improvement at one year was tested with the χ2 statistic. Secondary outcome measures are reported to describe the nature and pattern of change.

Results

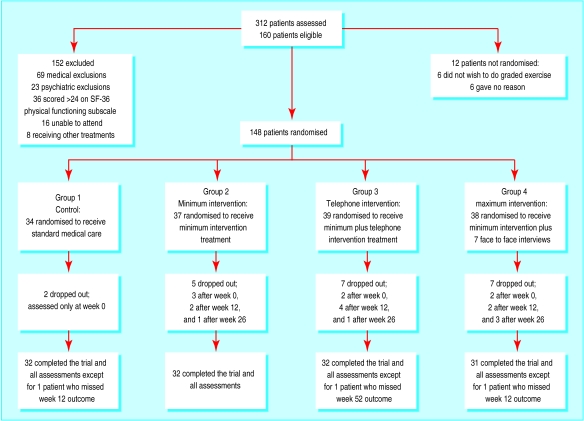

The figure shows the flow of patients through the trial. Of the 312 patients assessed, 152 did not meet the trial criteria (69 medical exclusions, 23 psychiatric exclusions, 36 scored over 24 on the SF-36 physical functioning subscale, 16 were unable to attend, and 8 were receiving other therapies). Twelve of the 160 eligible patients refused to participate. Twenty one (14%) of the 148 patients who entered the trial dropped out, a rate comparable to that in similar trials.11 Of these, 19 were in the intervention groups and dropped out during treatment (eight for medical reasons, seven for psychiatric reasons, four gave no reason, one emigrated, and one was dissatisfied with treatment). Table 2 shows patients' characteristics on admission to the trial. No significant differences were detected between the four groups on these measures.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients at baseline. Values are numbers or patients unless stated otherwise (95% confidence intervals in parentheses)

| Characteristic | Control group (n=34) | Minimum intervention (n=37) | Telephone intervention (n=39) | Maximum intervention (n=38) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 34 (10.5) | 34 (10.7) | 32 (9.5) | 33 (10.7) |

| Mean (SD) duration of symptoms (months) | 48.6 (38.5) | 51.2 (71.6) | 51.5 (43.7) | 55.0 (51.7) |

| Female | 24 | 28 | 33 | 31 |

| Working | 11 | 13 | 11 | 15 |

| Disability benefit | 15 | 17 | 16 | 16 |

| Antidepressants | 9 | 5 | 10 | 3 |

| Member of support group | 13 | 7 | 11 | 6 |

| No definitive diagnosis by GP | 13 | 16 | 13 | 13 |

| Belief in physical cause | 20 | 20 | 19 | 17 |

Treatment effects

Table 3 gives the scores for the primary outcome measures at baseline and follow up. At one year, significantly more patients had improved on the SF-36 physical functioning scale than in the control group. (F(3, 142)=24.15, P<0.001). The mean score in all three intervention groups was higher than in the control group (P<0.001), and no difference was observed between the intervention groups. Similarly, on the fatigue scale, improvement at one year follow up (F(3, 142)=24.99, P<0.001) was greater in each of the intervention groups than in the control group (P<0.001 for each comparison) but no differences were observed between the intervention groups.

Table 3.

Mean (95% confidence interval) scores on primary outcome measures at baseline and follow up at three, six, and 12 months

| Control group | Minimum intervention | Telephone intervention | Maximum intervention | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 physical functioning† | |||||

| Baseline | 16.3 (15.2 to 17.5) | 16.0 (15.0 to 17.0) | 15.8 (14.6 to 17.0) | 16.0 (14.8 to 17.0) | |

| 3 months | 16.3 (14.9 to 17.7) | 22.8 (21.1 to 24.4) | 22.3 (20.6 to 24.0) | 22.8 (21.2 to 24.3) | |

| 6 months | 17.2 (15.6 to 18.7) | 24.0 (22.4 to 25.6) | 23.0 (21.2 to 24.7) | 24.1 (22.6 to 25.6) | |

| 1 year | 16.9 (15.4 to 18.4) | 25.1 (23.3 to 26.8) | 24.3 (22.5 to 26.0) | 24.9 (23.4 to 26.4) | <0.001 |

| Fatigue scale‡ | |||||

| Baseline | 10.6 (10.4 to 10.9) | 10.4 (10.0 to 10.7) | 9.9 (9.2 to 10.6) | 10.2 (9.9 to 10.6) | |

| 3 months | 10.4 (10.1 to 10.8) | 5.0 (3.4 to 6.6) | 3.7 (2.3 to 5.2) | 4.3 (2.9 to 5.8) | |

| 6 months | 9.9 (9.1 to 10.8) | 3.8 (2.5 to 5.2) | 4.0 (2.5 to 5.5) | 3.4 (2.2 to 4.6) | |

| 1 year | 10.1 (9.3 to 10.8) | 3.2 (1.8 to 4.7) | 3.5 (2.1 to 4.9) | 3.1 (1.8 to 4.4) | <0.001 |

P values derived from one way analysis of covariance on scores at one year with initial scores and depression scores as covariates.

Score range 10-30, where 10=maximum impairment and 30=no limitation on physical activity.

Score range 0-11, where scores⩾4=excessive fatigue.

Only two of the 34 patients in the control group met our criteria for a clinically important improvement compared with 26/37 in the minimal intervention group, 27/39 in the telephone group, and 26/38 in the maximum intervention group (χ2=42.54, df=3, P<0.001). These proportions equated to numbers needed to treat of 1.55, 1.58, and 1.60 respectively.

Table 4 shows the changes in the secondary measures. Of those patients who completed educational intervention, 84% (80/95) reported being “very much better” or “much better” compared with 12% (4/32) of control patients.

Table 4.

Mean (95% confidence interval) scores on hospital anxiety and depression scale and sleep problem questionnaire at baseline and follow up at three, six, and 12 months

| Control group | Minimum intervention | Telephone intervention | Maximum intervention | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression† | |||||

| Baseline | 10.4 (8.9 to 11.8) | 9.3 (8.0 to 10.5) | 9.0 (7.8 to 10.2) | 9.0 (7.8 to 10.2) | |

| 3 months | 11.2 (9.6 to 12.9) | 6.1 (4.7 to 7.4) | 5.9 (4.5 to 7.3) | 5.8 (4.8 to 6.9) | |

| 6 months | 11.0 (9.2 to 12.9) | 5.4 (3.9 to 6.9) | 5.6 (4.3 to 6.9) | 5.0 (3.8 to 6.2) | |

| 1 year | 10.1 (8.4 to 11.7) | 4.2 (3.0 to 5.5) | 4.6 (3.2 to 6.0) | 4.2 (2.9 to 5.5) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety† | |||||

| Baseline | 11.2 (9.6 to 12.8) | 10.6 (9.1 to 12.1) | 10.0 (8.4 to 11.7) | 10.2 (8.8 to 11.7) | |

| 3 months | 11.4 (9.8 to 13.1) | 9.2 (7.3 to 10.7) | 7.7 (6.1 to 9.2) | 8.7 (7.2 to 10.1) | |

| 6 months | 10.6 (8.8 to 12.4) | 8.7 (7.1 to 10.2) | 7.5 (6.0 to 9.0) | 7.7 (6.2 to 9.2) | |

| 1 year | 10.1 (8.4 to 11.7) | 7.1 (5.8 to 8.5) | 6.5 (5.1 to 7.9) | 7.7 (6.1 to 9.3) | <0.01 |

| Sleep problem questionnaire‡ | |||||

| Baseline | 12.8 (11.1 to 14.5) | 12.4 (10.8 to 14.0) | 13.5 (12.1 to 15.0) | 13.0 (11.4 to 14.7) | |

| 3 months | 11.6 (9.8 to 13.5) | 9.0 (7.4 to 10.5) | 10.1 (8.2 to 11.9) | 8.7 (7.2 to 10.3) | |

| 6 months | 12.1 (10.1 to 14.1) | 7.4 (5.7 to 9.1) | 9.1 (7.2 to 11.0) | 8.2 (6.6 to 9.9) | |

| 1 year | 11.5 (9.7 to 13.4) | 6.7 (5.0 to 8.4) | 8.6 (6.8 to 10.3) | 7.1 (5.6 to 8.7) | <0.001 |

P values derived from one way analysis of covariance on scores at one year with initial scores and depression scores as covariates.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale: score range 0-21, where more than 10 indicates clinical depression or anxiety.

Score range 0-20, where 20 indicates maximum sleep problems.

Changes in beliefs

Seventy seven patients in the intervention groups completed questionnaires about their illness beliefs; two questionnaires were incomplete. Most patients (81%, 61/75) reported that they had believed their condition was caused by a persistent virus before treatment and 23% (17/75) reported maintaining this belief at one year. The proportion believing that their condition was due to a missed physical illness was 67% (50/75) at baseline and 13% (10/75) at one year. Only 15% (11/75) reported that they had believed that their condition was related to physical deconditioning at baseline whereas 81% (61/75) believed this after treatment. Eighty two per cent (63/77) indicated that they had avoided physical activity before treatment compared with only 6% (5/77) after treatment. The explanations of their symptoms convinced 94% (72/77) of the patients to carry out graded activity.

Discussion

The interventions were more effective in improving fatigue and physical functioning than standardised medical care. Mood, sleep, and disability scores also improved. These gains were maintained at one year follow up. Improvement in the control group was similar to that observed elsewhere.21

Of the patients who completed treatment, 81% met our improvement criterion. Although the intervention was generally beneficial, an intention to treat analysis showed that 32% of patients still complained of fatigue at one year despite a substantial improvement in physical functioning.

We found no significant differences between the three intervention groups. For many of the patients, the minimum intervention of two face to face sessions and up to four follow up telephone contacts was sufficient to bring about clinical gains. There was no evidence that further face to face or telephone contacts facilitated further improvement, although differences may emerge when longer term follow up data are collected.

Other trials in chronic fatigue syndrome reported encouraging results with cognitive behaviour therapy10,11 and graded exercise.21,22 In those trials, 60-74% of patients who completed treatment rated themselves as better or much better compared with 84% of patients who completed the interventions in the present trial. A recent review found that, “Cognitive behavioural therapy administered by highly skilled therapists in specialist centres is an effective intervention for people with chronic fatigue syndrome, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 2.”23 Our findings compare favourably with this outcome. Our intervention requires fewer sessions than cognitive behaviour therapy and could be carried out by a clinician without advanced training in psychological therapies.

Limitations

Our current study has several limitations, including the lack of a placebo control group that received equivalent therapist time and attention. However, other investigators have found that therapist time alone does not result in positive outcomes.11,21,22 After treatment, most patients attributed their improvement to changes of behaviour brought about by the physiological explanations they were given for their symptoms.

The subjective nature of fatigue symptoms makes objective measurement difficult, and self reported measures have to be used. Although overall outcome was assessed by appropriate well validated measures, independent assessment at baseline and one year would have allowed increased confidence in the data. We did not assess the economic costs associated with illness and benefits of treatment. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that our approach may be a cost effective and beneficial treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome.

What is already known on this topic

No serious underlying pathology has been identified in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome

Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome show evidence of disrupted physiological regulation, including physical deconditioning, sleep disturbance, and circadian dysrhythmia

Cognitive behaviour therapy targeted at changing illness beliefs and graded exercise helps some patients

What this study adds

Patients given physiological explanations for their symptoms and encouraged to do graded exercise were significantly better than those who received standardised care at one year

The approach may be as effective as cognitive behaviour therapy but is shorter and requires less therapist skill

Figure.

Flow of patients through trial

Footnotes

Funding: Linbury Trust.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Wessely S, Edwards RHT. Chronic fatigue. In: Greenwood R, Barnes M, McMillan T, Ward C, editors. Neurological rehabilitation. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. pp. 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson A, Hickie I, Lloyd A, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Boughton C, Dwyer J, et al. Longitudinal study of outcome of chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 1994;308:756–759. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6931.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams G, Piromohamed J, Minors D, Waterhouse J, Arendt J, Edwards RHT. Dissociation of body-temperature and melatonin secretion circadian rhythms in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Physiol. 1996;16:327–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1996.tb00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morriss R, Wearden A, Battersby L. The relation of sleep difficulties to fatigue, mood and disability in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:597–605. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)89895-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demitrack M, Dale J, Straus S, Laue L, Listwak S, Kruesi M, et al. Evidence for impaired activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Endcrinol Metab. 1991;73:1224–1234. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-6-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleare A, Bearn J, Allain T, McGregor A, Wessely S, Murray R, et al. Contrasting neuroendocrine responses in depression and chronic fatigue syndrome. J Affect Disord. 1995;35:293–289. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00026-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards R, Clague J, Gibson H, Helliwell T. Muscle metabolism, histopathology, and physiology in chronic fatigue syndrome. In: Straus S, editor. Chronic fatigue syndrome. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1994. pp. 241–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Lorenzo F, Xiao H, Mukherjee M, Harcup J, Suleiman S, Kadziola Z, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: physical and cardiovascular deconditioning. Q J Med. 1998;91:475–481. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.7.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wessely S, Hotopf M, Sharpe M. Chronic fatigue and its syndromes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharpe M, Hawton K, Simkin S, Surway C, Hackmann A, Klimes I, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for the chronic fatigue syndrome: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;312:22–26. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7022.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deale A, Chalder T, Marks I, Wessely S. Cognitive behavioural therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:408–414. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell P, Edwards R, Bentall R. The treatment of wheelchair-bound chronic fatigue syndrome patients: Two case studies of a pragmatic treatment approach. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1999;27:249–260. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharpe M, Archard L, Banarvala J, Borysiewicz L, Clare A, David A, et al. A report—chronic fatigue syndrome: guidelines for research. J R Soc Med. 1991;84:118–121. doi: 10.1177/014107689108400224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware J, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF36) Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zigmond A, Snaith R. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garratt A, Ruta D, Abdalla M, Buckingham J, Russell I. The SF36 health survey questionnaire: an outcome measure suitable for use within the NHS? BMJ. 1993;306:1440–1444. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkins D, Stanton B, Niemcryk S, Rose R. A scale for the estimation of sleep problems in clinical research. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:313–321. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Medical Health; 1976. Clinical global impressions; pp. 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wearden A, Morriss R, Mullis R, Strickland P, Pearson D, Appleby L, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trial of fluoxetine and graded exercise for chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:485–496. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.6.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fulcher K, White P. Randomised controlled trial of graded exercise in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 1997;314:1647–1652. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7095.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid S, Chalder T, Cleare A, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 2000;320:292–296. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7230.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]