Abstract

Introduction

The dopamine-type-1 receptor has been implicated in major depressive disorder (MDD) by clinical and preclinical evidence from neuroimaging, post-mortem and behavioral studies. To date, however, selective in vivo assessment of D1-receptors has been limited to the striatum in MDD-samples manifesting anger attacks. We employed the PET radioligand, [11C]NNC-112, to selectively assess D1-receptor binding in extrastriatal and striatal regions in a more generalized sample of MDD-subjects.

Methods

The [11C]NNC-112 nondisplaceable binding-potential (BPND) was assessed using PET in 18 unmedicated, currently-depressed subjects with MDD and 19 healthy controls, and compared between groups using MRI-based region-of-interest analysis.

Results

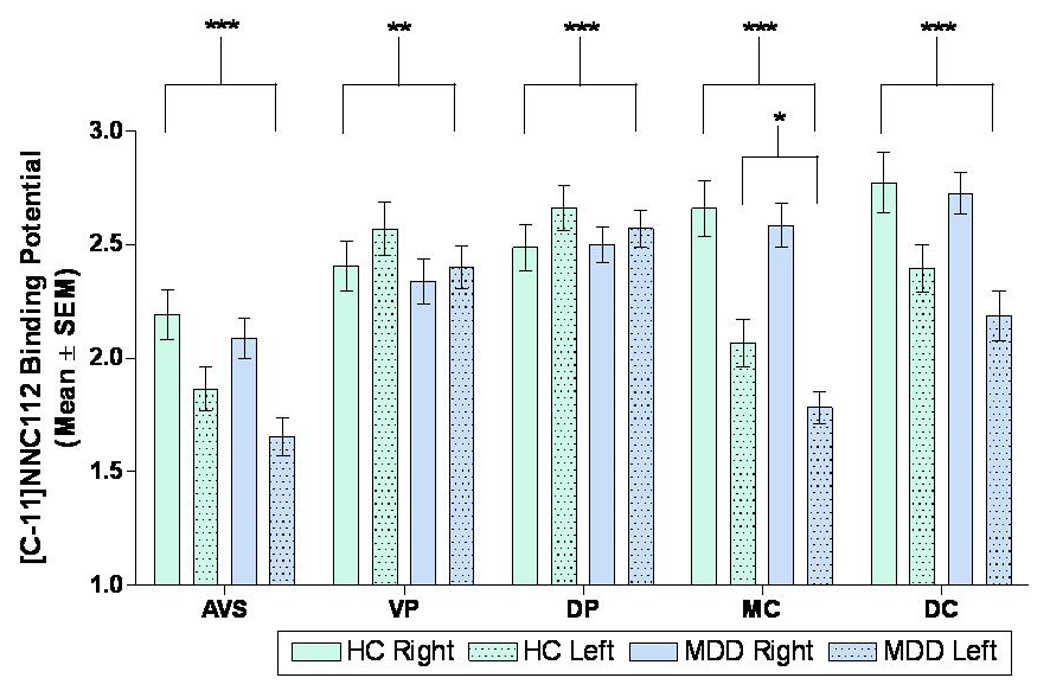

The mean D1-receptor BPND was reduced (14%) in the left middle caudate of the MDD group relative to control group (p<0.05). Among the MDD-subjects D1-receptor BPND in this region correlated negatively with illness duration (r= −0.53; p=0.02), and the left-to-right BPND ratio correlated inversely with anhedonia ratings (r=−0.65, p=0.0040). The D1receptor BPND was strongly lateralized in striatal regions (p<0.002 for main effects of hemisphere in accumbens area, putamen and caudate). In post hoc analyses, a group-by-hemisphere-by-gender interaction was detected in the dorsal putamen, which was accounted for by a loss of the normal asymmetry in depressed females (F=7.33,p=0.01).

Conclusions

These data extended a previous finding of decreased striatal D1-receptor binding in an MDD-sample manifesting anger attacks to a sample selected more generally according to MDD criteria. Our data also more specifically localized this abnormality in MDD to the left middle caudate, which is the target of afferent neural projections from the orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortices where neuropathological changes have been reported in MDD. Finally, D1-receptor binding was asymmetrical across hemispheres in healthy humans, compatible with evidence that dopaminergic function in the striatum is lateralized during reward processing, voluntary movement and self-stimulation behavior.

Keywords: Caudate, Striatum, anhedonia, g-protein coupled receptor

INTRODUCTION

The central dopaminergic system has been implicated in the modulation of emotional behavior, the pathophysiology of depression, and the mechanisms of antidepressant drugs, by clinical and preclinical evidence(Drevets et al. 1999; Nestler and Carlezon 2006; Nutt et al. 2006). In experimental animals the dopaminergic projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens shell and medial prefrontal cortex (PFC) were shown to play major roles in learning associations between operant behaviors or sensory stimuli and reward, and in mediating the reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse and natural rewards(Wise and Rompre 1989; Schultz 1997). These observations lead to the hypothesis that reduced mesocorticolimbic DA function underlies the anhedonia, amotivation and psychomotor slowing associated with major depression(Swerdlow and Koob 1987; Fibiger 1991; Nestler and Carlezon 2006).

A variety of experimental data support this hypothesis. Reductions in dopaminergic function associated with alpha-methyl-para-tyrosine administration can induce depressive symptoms in susceptible individuals(Bremner et al. 2003; Hasler et al. 2008). Conversely, dopamine receptor agonists (e.g., pramipexole) exert antidepressant effects in placebo-controlled studies(Willner 2000; Zarate et al. 2004). In MDD-subjects DA turnover appears abnormally decreased, as concentrations of the DA metabolite, homovanillic acid(HVA), consistently are reduced in the cerebrospinal fluid(CSF) and jugular vein plasma in vivo(Lambert et al. 2000; Willner 2000)--particularly in depressives who manifest psychomotor retardation or melancholic features(Asberg et al. 1984) and in the caudate and accumbens post mortem in suicide victims(Bowden et al. 1997). Neuroimaging studies of MDD showed reduced [11C]L-DOPA uptake across the blood-brain-barrier(Agren and Reibring 1994) and increased striatal binding to D2/D3-receptor radioligands that were sensitive to endogenous DA concentrations, although these latter findings were limited to cases who showed psychomotor slowing(Ebert et al. 1996; Drevets et al. 2005). In such cases the elevated D2/D3-receptor binding may have reflected either reduced intrasynaptic DA concentrations, or compensatory up-regulation of D2/D3-receptor density or affinity(Todd et al. 1996; Laruelle and Huang 2001). Nevertheless, studies whose samples were not predominantly composed of psychomotor slowed cases found no difference in D2/3-receptor levels during depression(Klimke et al. 1999; Parsey et al. 2001; Montgomery et al. 2007; Hirvonen et al. 2008). Similarly, some(Meyer et al. 2001) but not other(Brunswick et al. 2003; Argyelan et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2008) studies of striatal DA transporter(DAT) binding reported reduced availability in MDD-subjects versus controls.

The specific DA receptor subtypes that mediate dopaminergic function in reward processing, emotional behavior and depression remain incompletely understood, partly due to the paucity of highly selective agonists and antagonists. In mice phenotypic analysis of DA receptor knockouts identified roles for the D1, D2 and D3 receptor subtypes in mediating dopamine’s effects on reward processing and/or emotional behavior. A complex role for D1-receptors in particular was supported by both preclinical and clinical evidence. In genetically-engineered mice deletion of the D1-receptor attenuated the reinforcing properties of rewarding stimuli [reviewed in(Holmes et al. 2004)]. Nevertheless, the euphoric effects of cocaine appeared blunted by D1-receptor-like antagonist administration in cocaine addicts(Romach et al. 1999; Waddington et al. 2001; Holmes et al. 2004). Moreover, in rats the reduction in sucrose consumption resulting from chronic mild stress, a purported model of anhedonia, was associated with increased D1-receptor density in the caudate-putamen(but not the accumbens or amygdala)(Papp et al. 1994), and in humans with schizophrenia, D1-receptor antagonists alleviated “negative” symptoms such as anhedonia and amotivation(Den Boer et al. 1995; Karle et al. 1995).

With respect to other emotional states, in rats intra-amygdaloid injection of D1-receptor antagonists exerted anxiolytic effects(de la Mora et al. 2005) and impaired retention of inhibitory avoidance learning(fear-based memory)(Lalumiere et al. 2004). Moreover, D1-receptor knockout mice showed deficits in fear extinction and reversal learning (putative correlates of resilience to stress or adaptation to behavioral reinforcement, respectively), and abnormal long-term potentiation of synapses on PFC neurons(El-Ghundi et al. 1999; El-Ghundi et al. 2001; Huang et al. 2004). These data appeared consistent with evidence that an optimal range of D1-receptor stimulation is required to facilitate working memory, as intracortical administration of either agonists or antagonists for D1-receptors impairs working memory performance in rodents and primates(Arnsten et al. 1994; Williams and Goldman-Rakic 1995; Granon et al. 2000; Robbins 2000).

In MDD the D1-receptor has been assessed by genetic, post-mortem and neuroimaging studies. Although polymorphisms in the human D1-receptor gene have not been associated specifically with the vulnerability for developing MDD(Koks et al. 2006), one study(Severino et al. 2005)(but not another(Kato 2007)) found an association with bipolar disorder (BD). Post-mortem studies of D1-receptor binding found no difference in the striatum(Bowden et al. 1997) or right amygdala(Klimek et al. 2002) in MDD-subjects who were unmedicated at the time of death (n=28 and 11, respectively) versus controls, although one of these found increased D1-receptor density and reduced affinity in the accumbens in medicated suicide victims(Bowden et al., 1997). Finally, a PET-[11C]SCH-23390 study reported reduced D1-receptor binding in the striatum bilaterally in 10 depressed MDD-subjects with anger attacks(Dougherty et al. 2006). It remained unclear whether this finding would generalize to other MDD subtypes. In subjects with BD(n=10), a PET-[11C]SCH-23390 study reported no difference in striatal D1-receptor binding relative to controls, although only three of the subjects were depressed(Suhara et al. 1992). The latter study also reported reduced binding in the frontal cortex of BD-subjects, but because ~one-quarter of [11C]SCH-23390 binding in the frontal cortex is attributable to 5-HT2A receptor binding, this difference remained difficult to interpret(Ekelund J et al. 2006).

The recent development of a PET radioligand using (+)-5-(7-Benzofuranyl)-8-chloro-7-hydroxy-3-methyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepine (NNC-112), a potent and selective D1-receptor antagonist, provided sufficiently high specific-to-nonspecific binding ratios to permit meaningful assessment of D1-receptor binding in both extrastriatal and striatal tissues(Andersen et al. 1992; Halldin et al. 1998). The current study is the first application of [11C]NNC-112 in investigations of D1-receptor binding in mood disorders, and the first in vivo study of D1-receptor binding in depressed subjects selected more generally according to the criteria for MDD. We hypothesized that the mean D1-receptor BPND would be reduced in the striatum of MDD-subjects versus controls, based on the data reported in MDD-subjects with anger attacks(Dougherty et al. 2006). In addition, we sought to more specifically localize D1-receptor binding abnormalities in MDD using an MRI-based technique previously developed for characterizing the dopaminergic system in striatal subregions(Drevets et al. 1999, 2001).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Participants

Right-handed volunteers 18 to 55 years of age, who either met DSM-IV criteria for recurrent or chronic MDD in a current major depressive episode(n=18), or had no personal history of a major psychiatric disorder(n=19) were studied(Table 1). Diagnosis was established by an unstructured interview with a psychiatrist and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV(APA 1994). Exclusion criteria for all subjects included a history of psychosis, exposure to psychotropic drugs, cigarette smoking or any medication likely to affect cerebral function within the three weeks prior to scanning(eight for fluoxetine), major medical or neurological illnesses, lifetime history of substance-dependence, substance-abuse within one year, recent suicidal behavior or serious suicidal ideation, current pregnancy, peri- or post-menopause status. Depressed subjects with secondary anxiety disorders were not excluded. Additional exclusion criteria for the controls included having a first-degree relative with a mood, anxiety or psychotic disorder. Subjects provided written informed consent as approved by the NIMH IRB.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characterization of the study samples.

| Control (n=19) | MDD (n=18) | |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion Female (n) | 58% (11) | 61% (11) |

| Age (mean±SD) | 31 ± 8.5 | 31 ± 11 |

| Proportion Right-Handed (n) | 100% (19) | 100% (18) |

| Depression Ratings | ||

| MADRS (mean±SD) | 0.47 ± 1.2 | 22 ± 5.3 |

| IDS-C (mean±SD) | 0.59 ± 1.3 | 27 ± 6.5 |

| Anxiety Ratings | ||

| HAMA (mean±SD) | 0.59 ± 1.2 | 12 ± 4.3 |

| Anhedonia IDS_C Ratings (Mean ± SD) | 0.06 ± 0.2 | 9.4 ± 3.2 |

| Psychomotor Speed – Response latency on RVIP | 437±78 | 491±118 |

| Age-at-Illness-Onset (yrs) mean±SD (range) | N/A | 19 ± 10 (6 – 41) |

| Illness Duration (years) mean±SD (range) | N/A | 12 ± 8.5 (2 – 32) |

| Duration Medication-Free, Mos. mean±SD (range) | N/A | 23 ± 35 (4 – 96) |

| Treatment Naïve (n) | 19 | 11 |

| Subjects with Remote History of Suicide Attempts (n) | 0 | 4 |

| Prior Exposure to Antipsychotic Agent (n) | 0 | 1 |

| Remote History of Alcohol (2) or Marijuana (1) Abuse (n) | 0 | 3 |

| Comorbid Anxiety Disorder (n) | 0 | 5 |

Abbreviations. MADRS, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale; HAM-A, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; IDS-C, Inventory of Depressive Symptoms-Clinician Rated; RVIP, Rapid Visual Information Processing

Data Acquisition and Processing

The severity of depressive symptoms was rated using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale(MADRS)(Montgomery 1979) and the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms-Clinician Version(IDS-C). Anxiety symptoms were rated using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale(HAM-A(Hamilton 1959)), and anhedonia was assessed using the anhedonia subscale of the IDS-C. Psychomotor speed was assessed using the reaction time measured during performance of the Rapid Visual Information Processing (RVIP) task from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery(CANTAB; Cambridge Cognition Ltd, Cambridge, UK). These computerized tasks were presented on an Advantech computer(Model PP-120T-RT) with a 10 1/2 inch touch-screen monitor.

PET scans were acquired using a GE-Advance scanner in 3D-mode(reconstructed 3D spatial-resolution=6 mm full-width at half-maximum[FWHM]). The PET data were reconstructed using a Hanning-filter and Gaussian fit scatter correction method. An 8-minute transmission scan was acquired using rotating rods of 68Ge/68Ga, and used to perform measured attenuation correction of the emission image. [11C]NNC-112 was synthesized as described previously(Halldin et al. 1998). Following intravenous bolus administration of a mean injected dose=19.5±1.24 mCi (range 15.5–20.8) of high specific activity [11C]NNC-112, a 90-minute dynamic emission scan was acquired as 27 frames of increasing length(number × frame duration [min]:6×0.50; 3×1.0; 2×2.0; 16×5.0).

Head motion was minimized during scanning by stabilizing each subject’s head position a thermoplastic mask fixed to the scanner table. In addition, the PET data were corrected for head motion by aligning all frames to a mean image of frames 3 through 8, using AIR(Woods et al. 1992) as implemented in Medx(Sensor Systems Inc., Sterling, VA). To provide an anatomical framework for the PET analysis, MRI scans were acquired using a GE 1.5 or 3.0T scanner and T1-weighted pulse sequence optimized to enhance tissue-contrast resolution(voxel size=0.86×0.86×1.2 mm). The realigned PET frames were coregistered to the anatomical MRI for each subject using fMRIB's Linear Image Registration Tool and a mutual information cost-function(Jenkinson and Smith 2001).

Data Analysis

The D1-receptor binding parameter estimations were performed voxel-wise using a multilinear reference-tissue model(MRTM) using a receptor-free reference-region(cerebellum) without arterial data. The BPND values thus obtained were proportional to the receptor density(Bmax) and independent of blood flow(K1)(Ichise et al. 2003). The value of k′2 was estimated by the 3-parameter MRTM using regions-of-interest(ROI) time-activity curves for the striatum. The R1 images, which reflect relative blood flow, were used for image co-registration with MRI. The generation of parametric BPND images from the dynamic [11C]NNC-112 PET data was performed in PMOD 2.5(Mikolajczyk et al. 1998).

Hypothesis testing was performed in 5 striatal ROI defined over the anteroventral striatum(AVS; accumbens area, ventromedial caudate, anteroventral putamen), dorsal caudate(DC), middle caudate(MC), ventral putamen(VP), dorsal putamen(DP), as described previously(Bowden et al. 1997; Drevets et al. 2001). Based on evidence that DA release during reward processing is lateralized in healthy humans(Martin-Soelch et al. 2007; Tomer et al. 2008), hemisphere was included as a factor in the analyses. To allow comparison with previously reported negative findings from post-mortem studies of depression(Klimek et al. 2002), we examined binding in the amygdala post hoc.

Additional exploratory analyses were conducted post hoc in cortical regions known to contain moderately-high D1-receptor concentrations and to be implicated in the mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic system and the pathophysiology of MDD(Willner 1995): right and left insula/lateral orbitofrontal cortex(i.e., sulcal BA47)(Ongur et al. 2003) and anterior cingulate cortex(ACC; including subgenual and pregenual areas). Amygdala, insular and ACC ROI were defined as described in(Cannon et al. 2007).

The reference-region was defined in the cerebellar cortex, with the ROI situated at least one FWHM ventral to the occipital and temporal cortices, and away from the cerebellar vermis and brain edge.

Statistical Analysis

The mean BPND for each ROI was compared between groups using a linear mixed-model and the heterogeneous compound-symmetry covariance-matrix performed using SPSS. For ROI where the model indicated significant group effects, post-hoc comparisons of BPND across groups were performed using unpaired t-tests. In regions where group effects were detected the relationship between D1-receptor BPND and clinical ratings of depression, anxiety and anhedonia were assessed post hoc by computing Spearman’s bivariate correlation coefficients(rho, ρ).

RESULTS

The groups did not differ significantly for mean age or gender composition(Table 1). Mean depression, anxiety and anhedonia ratings were greater(p<0.001, T=−4 to −17) in MDD-subjects than controls(Table 1). Reaction times on the RVIP did not differ significantly between the MDD and control groups(t=−1.50, p=0.15). Performance measured by the number of omission (HC 4.5±2.7, MDD 6.9±5.5, t=−1.64, p=0.12) or commission errors (HC 0.33±1.29, MDD 1.35±1.83, T= −1.794, p=.083) on the RVIP also did not differ significantly between groups. Five MDD-subjects had comorbid anxiety disorders[generalized social phobia(n=4), specific phobia(n=1)]. Two MDD-subjects had a remote history of alcohol abuse and one a remote history of marijuana abuse.

The rank order of the [11C]NNC BPND values was caudate, putamen>AVS>amygdala>insula > ACC >cerebellum(Table 2), consistent with the relative D1-receptor densities measured post-mortem in humans(Cortes et al. 1989).

Table 2.

The mean and standard deviation of regional [C-11]NNC-112 binding potential values. The a priori hypothesis was tested in the striatal regions-of-interest (caudate, putamen). Analyses of D1-receptor binding in extrastriatal tissues were performed post-hoc.

| Region | Healthy Control | Major Depressive Disorder | Group Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p | ||

| VP | right | 2.41 | 0.47 | 2.34 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.64 |

| left | 2.57 | 0.51 | 2.40 | 0.40 | 1.15 | 0.26 | |

| DP | right | 2.49 | 0.45 | 2.50 | 0.33 | −0.11 | 0.92 |

| left | 2.66 | 0.42 | 2.57 | 0.34 | 0.72 | 0.48 | |

| MC | right | 2.66 | 0.53 | 2.59 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.64 |

| left | 2.07 | 0.46 | 1.78 | 0.30 | 2.21 | 0.03* | |

| DC | right | 2.77 | 0.58 | 2.73 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.78 |

| left | 2.40 | 0.45 | 2.19 | 0.46 | 1.39 | 0.17 | |

| AVS | right | 2.19 | 0.47 | 2.09 | 0.37 | 0.73 | 0.47 |

| left | 1.86 | 0.42 | 1.67 | 0.35 | 1.65 | 0.11 | |

| Amygdala | right | 1.64 | 0.55 | 1.52 | 0.43 | 0.79 | 0.44 |

| left | 1.63 | 0.76 | 1.47 | 0.43 | 0.88 | 0.39 | |

| Insula | right | 0.70 | 0.13 | 0.69 | 0.14 | −0.42 | 0.68 |

| left | 0.69 | 0.12 | 0.68 | 0.16 | −1.40 | 0.17 | |

| ACC | bilateral | 1.02 | 0.23 | 1.03 | 0.23 | −0.45 | 0.66 |

Abbreviations: ACC-anterior cingulate cortex; AVS-anteroventral striatum; DC-dorsal caudate; DP-dorsal putamen; MC-middle caudate; VP-ventral putamen

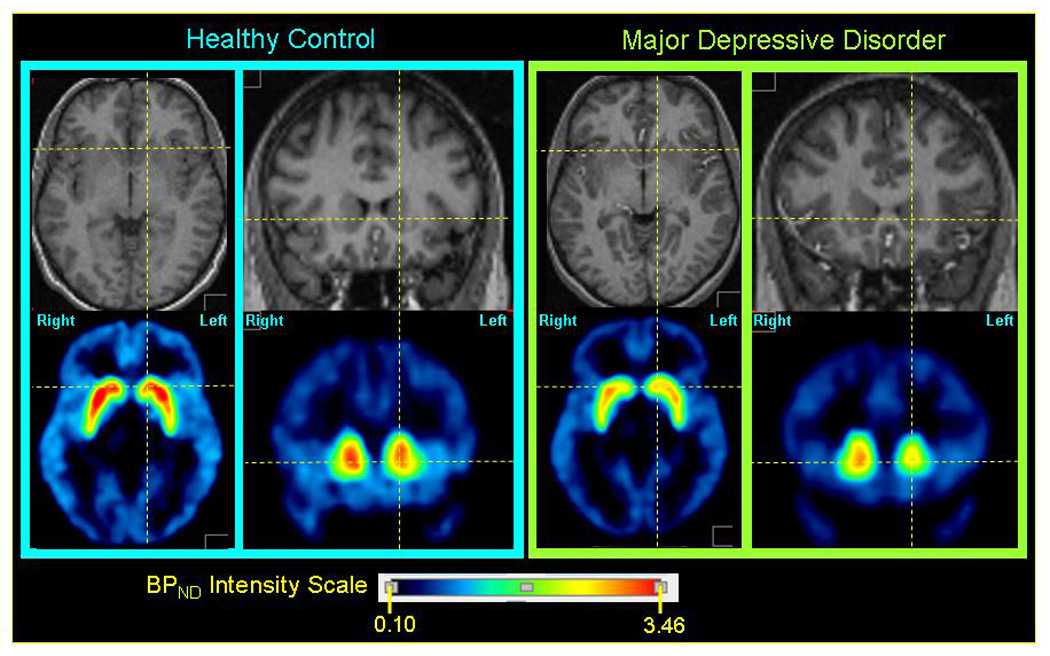

The mean D1-receptor BPND was 14% lower in the left MC of the MDD-subjects versus controls(T=2.21, p=0.03, Figure 1, Figure 2; Table 2). The magnitude of this difference was similar after removing the 3 subjects with a remote history of substance abuse (12.6%), the 7 previously-medicated MDD-subjects(13.5%) or the 5 subjects with co-morbid phobias(11%). In the remaining ROIs mean D1-receptor BPND did not differ between the control and MDD groups(Table 2).

Figure 1. Dopamine-D1 receptor binding potential in healthy control and MDD groups in the left and right hemispheres for the striatal regions-of-interest.

*p<0.05: D1-receptor binding was significantly lower in the left middle caudate (MC) in the MDD group relative to control group.

**p<0.05, ***p<0.001: The main effect of hemisphere on BPND was significant in the anteroventral striatum (AVS), ventral putamen (VP), dorsal putamen (DP), middle caudate (MC), and dorsal caudate (DC) regions-of-interest

Figure 2. Representative parametric dopamine-D1 receptor BPND images through the striatum in a control subject (left panel) and an MDD subject (right panel).

Within each panel the upper row of images show axial (left) and coronal (right) sections through the anatomical MRI, on which the regions-of-interest (ROI) were defined (Drevets et al. 2001), and the lower row of images show parametric images of the non-displaceable component of the D1-recetor binding potential (BPND) modeled from PET emission images. The MRI and PET images for each subject are co-registered. The axial images show the plane containing both the anterior and posterior commissures. The orthogonal lines locate approximately the center of the caudate head on this bi-commissural plane. The coronal sections pass through the anterior striatum, which at the level shown is composed predominantly of the caudate head. The middle caudate region is evident in the coronal sections, where it is situated immediately above the bicommissural plane (marked by the horizontal line). The D1-receptor BPND consistently was higher in the right caudate than the left in both groups (see figure 1, figure 3), as evinced in these representative images. The mean BPND value in the left middle caudate of the MDD group was lower than in the control group (figure 1).

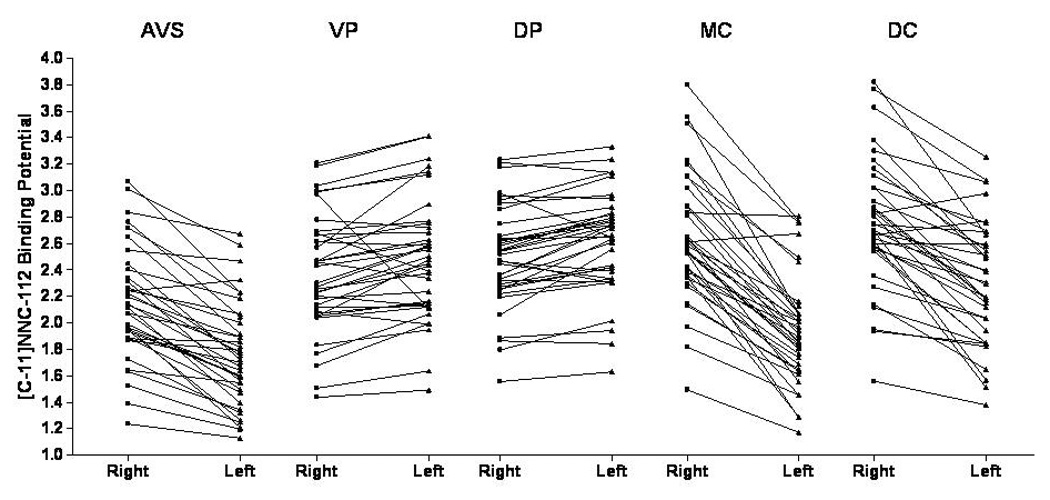

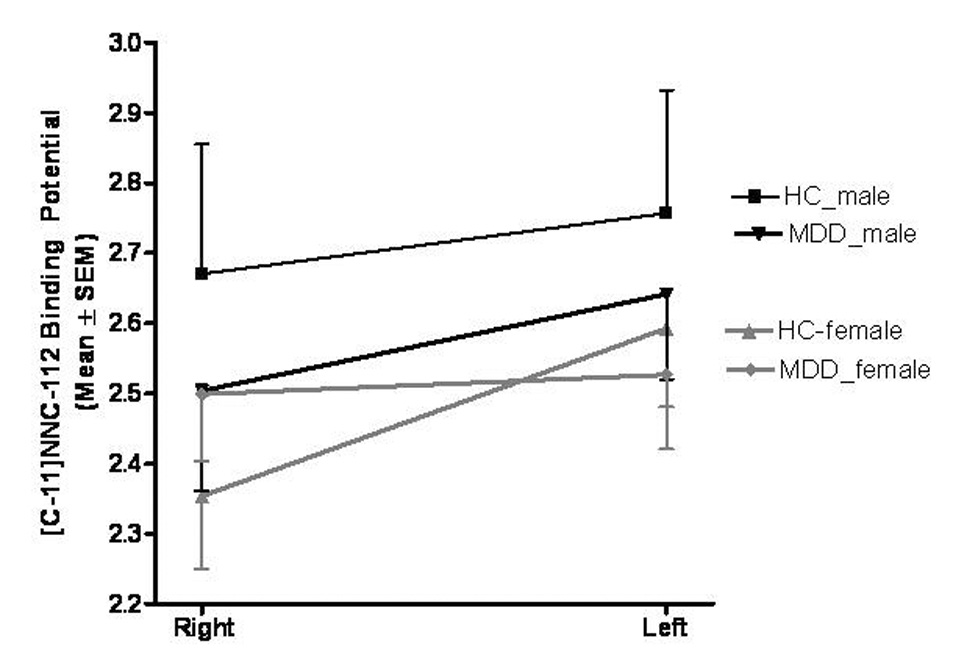

In post-hoc assessments, a main effect of hemisphere was evident in several regions (Figure 1, Figure 3), including AVS(F=87.8, p=8.01e−11), VP(F=8.84, p=3.10e−2), DP(F=25.5, p=1.56e−5), MC(F=308, p=1.09e−5) and DC(F=98.5, p=1.77e−4). A group-by-gender-by-hemisphere interaction(F=7.33, p=0.011) was detected in the DP, which was accounted for by a greater interhemispheric difference in BPND in female controls versus female MDD-subjects(Figure 6). This interaction remained significant after including age as a covariate, or after removing from analysis the subjects who had a remote history of substance abuse(F=4.44, p=0.044), previous psychotropic medication exposure(F=6.17, p=0.020) or co-morbid phobia(F=5.83, p=0.023).

Figure 3. Dopamine-D1 receptor binding potential in the left and right hemispheres for each striatal region-of-interest showing the consistency of laterality effects. The left- and right-sided values corresponding to a single participant are connected by a line.

Main effects of hemisphere on regional binding potentials were significant in all five regions-of-interest (see figure 1 and results section for significance levels).

Figure 6. Mean (+/− SEM) binding potential values for the right and left dorsal putamen separated by sex and diagnosis. In females with MDD the difference in D1-receptor BPND between the right and left hemispheres of the dorsal putamen was significantly less than that of the female controls.

In the dorsal putamen the group-by-gender-by-hemisphere interaction was significant (F=7.33, p=0.011). Abbreviations: HC, healthy control; MDD, major depressive disorder.

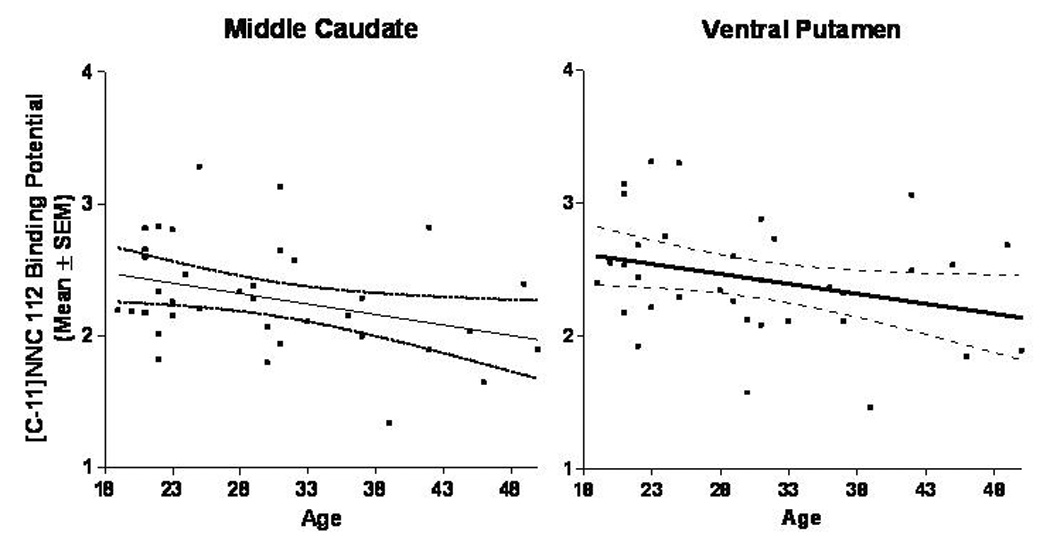

Age correlated with BPND in the left VP(ρ=−0.34, p=0.04), left DP(ρ=−0.33, p=0.04), right MC(ρ=−0.38, p=0.02), bilateral DC(left: ρ =−0.39, p=0.02; right: ρ =−0.38 p=0.02) and left insula(ρ =−0.42, p=0.01). The relationship between BPND and age showed a trend toward significance in right VP(ρ=−0.32, p=0.06), left MC(ρ=−0.29, p=0.08) and left insula(ρ=−0.32, p=0.052) but did not approach significance(p>.10) in the right DP, AVS, ACC, or amygdala. Analyses were covaried for age where relevant.

A main effect of gender on BPND was significant in the AVS(F=4.21, p=0.048), VP(F=7.28, p=0.043), MC(F=9.72, p=0.026), and DC(F=9.77, p=0.026) but not in the DP(F=1.38, p=0.249). There were no significant group-by-gender interaction in any region(p>0.1).

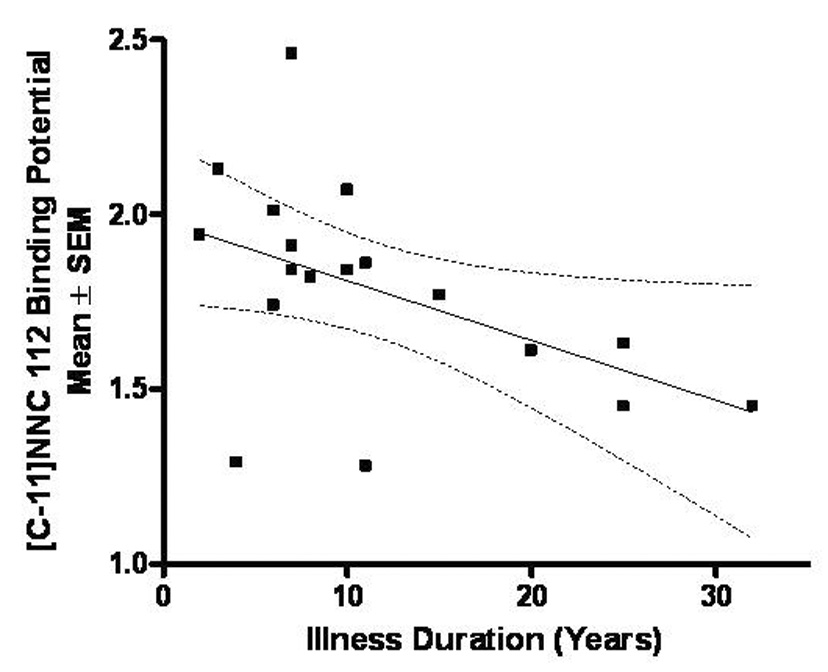

Exploratory, post hoc clinical correlations showed that BPND values in the left MC correlated inversely with illness duration(r= −0.53, p=0.02; Figure 4), but did not correlate significantly with depression(MADRS), anxiety(HAM-A) or anhedonia(IDS-C anhedonia subscale) severity(i.e., p>0.05). Reaction times on the RVIP correlated negatively with D1-receptor binding in the left MC in controls(r=−0.453, p=0.007) but not MDD-subjects(r= −0.096, p=0.358). The ratio of left-to-right BPND values in the MC correlated inversely with IDS-C anhedonia subscale ratings(r=−0.65, p=0.0040) but not with depression or anxiety ratings(p>0.4). MDD-subjects with comorbid phobias did not differ in D1-receptor BPND in the left MC than non-phobic depressives.

Figure 4. Relationship between dopamine-D1 receptor binding potential in the left middle caudate and illness duration in the MDD sample.

The D1-receptor binding potential in the left middle caudate correlated inversely (r=−0.531, p=0.02) with illness duration (calculated as time since illness onset).

Depression severity correlated negatively with BPND in right DP(MADRS ρ=−0.61, p=0.007, Figure 6). Anxiety severity(HAM-A) correlated negatively with BPND in right DP(ρ=−0.48, p=0.045). Anhedonia ratings, age-at-onset, and illness-duration did not correlate significantly with BPND in the DP(p>.05). In right DP, MDD-subjects with comorbid phobias showed lower D1-receptor BPND than non-phobic depressives(Z=−2.3, p=0.019).

Mean BPND values for depressed subjects who previously were exposed to psychotropic medications(n=7) showed no significant difference versus drug-naive subjects(n=11) in any region(p>.10).

DISCUSSION

The mean D1-receptor binding was 14% lower in the left MC of MDD-subjects versus healthy controls(Figure 1). Moreover, while significant differences in D1-receptor binding between the right and left hemispheres existed in controls, this normal asymmetry was absent in the DP in depressed females(Figure 6). Post-hoc assessments in the MDD-sample showed that D1-receptor binding in the left MC correlated inversely with illness duration and anhedonia ratings. In addition, the left MC D1-receptor binding correlated inversely with psychomotor speed in the controls but not the depressives.

The abnormalities in striatal BPND in MDD likely reflect alterations in D1-receptor density and/or affinity for [11C]NNC-112. Although [11C]NNC-112 binding is reversible in vivo(Abi-Dargham et al. 2000), it is insensitive to displacement by endogenous dopamine(Chou et al. 1999). Among DA receptors NNC-112 is highly selective for D1-receptors(e.g., the D1:D2 receptor binding ratio=4500)(Ekelund et al. 2007). The major limitation in specificity is that [11C]NNC-112 is only 2–3-fold more selective for D1-receptors than 5-HT2A receptors(Ekelund et al. 2007). Thus in the frontal cortex, where the 5-HT2A receptor and D1-receptor concentrations are comparable, up to 25% of [11C]NNC-112 binding is attributable to 5-HT2A-receptor binding(Ekelund J et al. 2006; Slifstein et al. 2007). In the striatum, however, where the ratio of D1:5-HT2A receptor density is relatively higher, the 5-HT2A contribution to the measured BPND is negligible(Slifstein et al. 2007). Thus, the abnormalities observed in the MC and DP in MDD most likely reflect differences in D1-receptor binding.

The mean 14% decrement in D1-receptor BPND in the left MC in our MDD-subjects appeared consistent with the 13% reduction in binding in the left striatum reported by Dougherty et al (2002) in MDD-subjects with anger attacks. Our data extended this previous finding by showing that the left striatal D1-receptor binding also was decreased in a depressed sample selected more generally according to MDD criteria. We did not observe any abnormality in the right striatum, however, raising the possibility that a deficit in right striatal D1-receptor binding may be specific to MDD-subjects with anger attacks.

Our data more specifically localized the abnormality in left striatal D1-receptor binding in MDD to the left MC, which showed the greatest magnitude-of-difference and effect-size across the striatal ROI(figure 1, figure 3). Because of the proximity of the MC to other striatal ROI, measured signals from the MC were weakly influenced by those from the AVS and DC which were partly continuous with the MC(Drevets et al.1999, 2001). Since parts of these ROI were separated by less than the 6 mm resolution of our PET measures, demonstrating differential regional abnormalities in MDD depended upon showing that the mean difference in BPND was greater in the MC than in the DCA or AVS. This approach was facilitated by the low [11C]NNC-112 specific binding in extrastriatal areas, which reduced the number of comparisons required across adjacent regions. The ability to assess relative differences in radiotracer concentration across conditions in ROI separated by less than the FWHM resolution is central to PET’s utility in localizing voxels of maximal difference in brain mapping studies(Fox et al. 1986; Friston et al. 1996). Because of these spatial resolution limitations, however, the non-significant trends seen in the left AVS and left DC(figure 1) are difficult to interpret since they may reflect spilling in of radioactivity from the MC(Links et al. 1996).

The MC region is the major striatal target of predominantly ipsilateral, afferent projections from the ACC and orbitofrontal cortex(OFC)(Ferry et al. 2000; Haber et al. 2006). Since the grey matter volume and/or neuronal counts in these cortical areas is reduced in MDD(Drevets et al. 2008), the regional specificity of the reduction in D1-receptor binding to the MC raises the possibility that this abnormality reflects a reduction in afferent neuronal terminals from the cortex, and thus in the density of synapses where D1-receptors are expressed post-synaptically. This hypothesis appears compatible with findings that in MDD both the reduction in D1-receptor binding in the MC(figure 1) and the reduction in grey matter volume in the ACC and OFC are predominantly left-lateralized(Drevets et al. 2008). This hypothesis may also be compatible with the finding that the D1-receptor binding in the left MC correlated inversely with illness duration(figure 4), since the reductions in ACC volume reportedly worsen across time in mood disorders(Koo et al. 2008). In contrast, perturbations in D1-receptor binding in MDD may be less likely to reflect local changes in receptor expression associated with changes in DA release, as the severe DA deficiency state accompanying Parkinson’s Disease is not associated with changes in D1-receptor binding or density(Pimoule et al. 1985; Shinotoh et al. 1993). Moreover, while changes in D1-receptor regulation at the level of G-protein coupling may exist in the DA depleted striatum(Gerfen et al. 2002), such a change would not likely be evinced by corresponding changes in D1-receptor antagonist binding to PET radioligands(Pimoule et al. 1985; Shinotoh et al. 1993) which typically bind to receptors in high versus low affinity states with comparable potency.

Post-hoc analyses revealed an altered interhemispheric ratio of D1-receptor BPND that differed significantly between depressed and control females in the DP. Specifically, the depressed females showed a loss of the asymmetry in D1-receptor binding that was evident in the controls(Figure 6). This difference was explained by D1-receptor BPND values that were non-significantly lower in the left DP and non-significantly higher in the right DP in depressed females versus control females(figure 6).

In other striatal regions the D1-receptor binding also showed highly significant laterality effects in healthy controls, which did not differ significantly between groups. In the caudate and AVS(accumbens area), the BPND was lower in the left hemisphere than the right. In contrast, in the putamen the direction of the laterality effect was reversed(left >right). This difference between caudate and putamen may explain the absence of laterality effects in striatal [11C]SCH-23390 binding in(Dougherty et al. 2006), who combined caudate and putamen into a single ROI. Other studies employing neuroimaging or autoradiographic techniques to assess D1-receptor binding in depressed or healthy humans(De Keyser et al. 1988; Suhara et al. 1991; Suhara et al. 1992; Bowden et al. 1997) or experimental animals(Cortes et al. 1989; Camps et al. 1990) did not examine laterality effects.

Asymmetrical D1-receptor binding across hemispheres is consistent with several reports of lateralized function within the dopaminergic system. The amount of DA release in human striatal subregions in response to unpredicted reward(Martin-Soelch et al. 2007), DA release in the rodent caudate during voluntary behavior(Yamamoto et al. 1982), and preference for self-stimulation induced by localized amphetamine administration in rats all show prominent laterality effects(Glick et al. 1980; Glick et al. 1981). In healthy humans greater D2-receptor availability in the left relative to the right striatum was associated with greater positive incentive motivation (Tomer et al. 2008). In right-handed humans DA concentrations were higher in the left putamen than the right(Glick et al. 1982; de la Fuente-Fernandez et al. 2000), and in marmosets levels of DA and HVA were higher in the right caudate and putamen than the left(Silva et al. 2007). Consistent with these data humans also showed higher dopamine transporter density in the left putamen and caudate versus the right, irrespective of handedness(van Dyck et al. 2002). [Although the lateralization of motor dominance(“handedness”) has been associated with variation in elements of the dopaminergic system including COMT(Savitz et al. 2007), it remains unclear whether handedness also would influence D1-receptor BPND.] Finally, our finding that the loss of normal asymmetry in D1-receptor BPND in MDD appeared specific to females was notable given evidence that the direction of asymmetry preference for self-stimulation in rats showed prominent sex-effects(Glick and Badalamenti 1986).

Since the mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic system plays major roles in the neural processing of reward and motivation, it is conceivable that either a deficit in dopaminergic function in the left MC, or alterations in the interhemispheric ratio of D1-receptors that may result from such a deficit, may disrupt the normally lateralized function of this system and thereby contribute to the depressed mood, anhedonia and amotivation associated with MDD(Nestler and Carlezon 2006; Liu et al. 2008). Compatible with this hypothesis, the ratio of left-to-right D1-receptor binding in the MC correlated inversely with the IDS-C anhedonia subscale(r=−0.65, p=0.0040). In the left MC functional abnormalities have been identified during reward processing in MDD. In independent samples of MDD-subjects the magnitude of DA release during unpredicted monetary reward and the hemodynamic response to anticipated monetary reward were abnormally blunted specifically in the left MC(Drevets 2008).

The relationship between the response latencies on a sustained attention task (RVIP) and D1-receptor binding in the left MC in healthy controls suggests that the abnormal D1-binding group in MDD also may play a role in the psychomotor or cognitive impairment associated with MDD. The mean response latency was 12% slower in depressives than controls, as expected(Tavares et al. 2003), although we were underpowered to establish the statistical significance of this difference. Although reaction times measured on the RVIP reflect both psychomotor speed and sustained attention, these variables generally are confounded on neuropsychological assessments of psychomotor speed. In controls the response latencies correlated inversely with BPND in the left MC (explaining 20.5% of the variance) implying the reduction in D1-receptor binding in this region in MDD may contribute to the psychomotor slowing associated with depression. The absence of a normal correlation between reaction time and MC-BPND in the MDD group also may be compatible with this hypothesis. Notably, psychomotor slowing previously was associated with reduced dopaminergic function in the left caudate in MDD, as (Martinot et al. 2001) reported that [18F]DOPA was reduced specifically in the left caudate in MDD patients with psychomotor retardation compared to both healthy controls and MDD patients without psychomotor slowing.

The inverse correlation between D1-receptor binding and age is consistent with the results of previous PET(Suhara et al. 1991; Iyo and Yamasaki 1993; Wang et al. 1998) or autoradiography studies(Klimek et al. 2002) conducted in humans or experimental animals(Suzuki et al. 2001). In humans Wang et al. (1998) reported a 6–7% decline in [11C]SCH-23390 binding to D1-receptors per decade in the caudate and putamen, comparable to the 3–6% decline in the BPND for [11C]NNC-112 per decade detected herein (assessed relative to the y-intercept for predicted value at birth; figure 5). In contrast, the relationship between BPND and age was not significant in the amygdala, consistent with the data of Klimek et al.(2002) who observed no significant age effect on D1-receptor density measured post mortem in the human amygdala.

Figure 5. Relationships between age and D1-receptor BPND in the middle caudate and ventral putamen for all subjects.

Age correlated negatively with [11C]NNC-112 BPND in the middle caudate, ventral putamen, and most of other striatal regions examined (ρ=−0.33 to −0.42, p=0.01 to 0.04; see text).

A limitation of our study was that we modeled the BPND for [11C]NNC-112 using a simplified reference tissue model to avoid arterial cannulation. This approach used the time-tissue radioactivity concentration in a reference region, the cerebellum, to estimate the concentration of free plus non-specifically bound radiotracer in all regions. However, without arterial plasma we were unable to measure the distribution volume of [11C]NNC-112 in the cerebellum. Consequently, a difference in BPND between groups could have been accounted for by abnormal [11C]NNC-112 binding either in the region-of-interest or the reference tissue. However, an abnormality of tracer uptake in the reference tissue could not account for the regionally specific group difference or the group-by-gender-by-hemisphere interaction found in the left MC and the DP, respectively.

In conclusion, reduced D1-receptor binding in the left MC, and in females an altered symmetry in D1-receptor binding in the DP, may contribute to dysfunction within the central dopaminergic system during depression. The prominent laterality effects we observed for striatal D1-receptor binding converges with other evidence indicating that DA concentrations are lateralized within the striatum(Glick et al. 1982; de la Fuente-Fernandez et al. 2000; Silva et al. 2007), and that the function of the central dopaminergic system in the striatum is lateralized during reward processing(Martin-Soelch et al. 2007), voluntary movement(Yamamoto et al. 1982) and self-stimulation behavior(Glick et al. 1980; Glick et al. 1981; Glick and Badalamenti 1986). Since dopaminergic projections into the striatum modulate the neural processing of reward learning, motivated behavior and psychomotor activity, alterations in the interhemispheric ratio of D1-receptor binding conceivably may disrupt the normally lateralized function of this system, and thereby contribute to the depressed mood, psychomotor slowing, anhedonia and amotivation that characterize depression.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Victor Pike, Robert Innis and Masahiro Fujita for providing the radioligand, Peter Herscovitch, M.D. and the Clinical Center PET Department for technical assistance, Michele Drevets, R.N. and Joan Williams, R.N., for evaluation and recruitment of the research subjects, the staff of the NIH Clinical Center, Allison Nugent, Stephen Fromm, Summer Peck, Suzanne Wood, Kelly Anastasi and Laurentina Cizza for assistance in data management, and Dave Luckenbaugh, Ph.D. for advice regarding the statistical analysis of the PET data. Funding: This study was supported by the intramural research program of the NIH/NIMH and a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: No author has a potential conflict-of-interest related to this work.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Martinez D, Mawlawi O, Simpson N, Hwang DR, Slifstein M, Anjilvel S, Pidcock J, Guo NN, Lombardo I, Mann JJ, Van Heertum R, Foged C, Halldin C, Laruelle M. Measurement of striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D1 receptor binding potential with [11C]NNC 112 in humans: validation and reproducibility. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20(2):225–243. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200002000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agren H, Reibring L. PET studies of presynaptic monoamine metabolism in depressed patients and healthy volunteers. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1994;27(1):2–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen PH, Gronvald FC, Hohlweg R, Hansen LB, Guddal E, Braestrup C, Nielsen EB. NNC-112, NNC-687 and NNC-756, new selective and highly potent dopamine D1 receptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;219(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90578-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) Washington, D.C.: APA Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Argyelan M, Szabo Z, Kanyo B, Tanacs A, Kovacs Z, Janka Z, Pavics L. Dopamine transporter availability in medication free and in bupropion treated depression: a 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT study. J Affect Disord. 2005;89(1–3):115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Cai JX, Murphy BL, Goldman-Rakic PS. Dopamine D1 receptor mechanisms in the cognitive performance of young adult and aged monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;116(2):143–151. doi: 10.1007/BF02245056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asberg M, Bertilsson L, Martensson B. CSF monoamine metabolites, depression, and suicide. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1984;39:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden C, Theodorou A, Cheetham SC, Lowther S, Katona CL, Crompton MR, Horton RW. Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor binding sites in brain samples from depressed suicides and controls. Brain Res. 1997;752(1–2):227–233. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Ng CK, Vermetten E, Nazeer A, Oren DA, Berman RM, Charney DS. Regional brain metabolic correlates of alpha-methylparatyrosine-induced depressive symptoms: implications for the neural circuitry of depression. Jama. 2003;289(23):3125–3134. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunswick DJ, Amsterdam JD, Mozley PD, Newberg A. Greater availability of brain dopamine transporters in major depression shown by [99m Tc]TRODAT-1 SPECT imaging. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1836–1841. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps M, Kelly PH, Palacios JM. Autoradiographic localization of dopamine D 1 and D 2 receptors in the brain of several mammalian species. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1990;80(2):105–127. doi: 10.1007/BF01257077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon DM, Ichise M, Rollis D, Klaver JM, Gandhi SK, Charney DS, Manji HK, Drevets WC. Elevated Serotonin Transporter Binding in Major Depressive Disorder Assessed Using Positron Emission Tomography and [(11)C]DASB; Comparison with Bipolar Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou YH, Karlsson P, Halldin C, Olsson H, Farde L. A PET study of D(1)-like dopamine receptor ligand binding during altered endogenous dopamine levels in the primate brain. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146(2):220–227. doi: 10.1007/s002130051110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes R, Gueye B, Pazos A, Probst A, Palacios JM. Dopamine receptors in human brain: autoradiographic distribution of D1 sites. Neuroscience. 1989;28(2):263–273. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Keyser J, Dierckx R, Vanderheyden P, Ebinger G, Vauquelin G. D1 dopamine receptors in human putamen, frontal cortex and calf retina: differences in guanine nucleotide regulation of agonist binding and adenylate cyclase stimulation. Brain Res. 1988;443(1–2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente-Fernandez R, Kishore A, Calne DB, Ruth TJ, Stoessl AJ. Nigrostriatal dopamine system and motor lateralization. Behav Brain Res. 2000;112(1–2):63–68. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Mora MP, Cardenas-Cachon L, Vazquez-Garcia M, Crespo-Ramirez M, Jacobsen K, Hoistad M, Agnati L, Fuxe K. Anxiolytic effects of intra-amygdaloid injection of the D1 antagonist SCH23390 in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2005;377(2):101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Boer JA, van Megen HJ, Fleischhacker WW, Louwerens JW, Slaap BR, Westenberg HG, Burrows GD, Srivastava ON. Differential effects of the D1-DA receptor antagonist SCH39166 on positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;121(3):317–322. doi: 10.1007/BF02246069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DD, Bonab AA, Ottowitz WE, Livni E, Alpert NM, Rauch SL, Fava M, Fischman AJ. Decreased striatal D1 binding as measured using PET and [11C]SCH 23,390 in patients with major depression with anger attacks. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23(3):175–177. doi: 10.1002/da.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets W. Neural Circuits Underlying Anhedonia in Major Depressive Disorder. BIOL PSYCHIATRY. 2008;63(supplement 1)(7):110S. [Google Scholar]

- Drevets W, Gadde K, Krishnan K. Neuroimaging studies of mood disorders. In: Charney D, Nestler ME, Bunney BS, editors. The Neurobiological Foundation of Mental Illness. 2005. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Gautier C, Price JC, Kupfer DJ, Kinahan PE, Grace AA, Price JL, Mathis CA. Amphetamine-induced dopamine release in human ventral striatum correlates with euphoria. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(2):81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Price JC, Kupfer DJ, Kinahan PE, Lopresti B, Holt D, Mathis C. PET measures of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in ventral versus dorsal striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(6):694–709. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML. Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213(1–2):93–118. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D, Feistel H, Loew T, Pirner A. Dopamine and depression--striatal dopamine D2 receptor SPECT before and after antidepressant therapy. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;126(1):91–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02246416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekelund J, Narendran R, Guillain O, Castrillon J, H D, Slifstein M, Abi-Dargham A, L M. Pharmacological selectivity of the in vivo binding of [11C]NNC 112 and [11C]SCH 23390 in the cortex. A PET study in baboons. Neuroimage. 2006;31(Supp 2):T111. [Google Scholar]

- Ekelund J, Slifstein M, Narendran R, Guillin O, Belani H, Guo NN, Hwang Y, Hwang DR, Abi-Dargham A, Laruelle M. In vivo DA D(1) receptor selectivity of NNC 112 and SCH 23390. Mol Imaging Biol. 2007;9(3):117–125. doi: 10.1007/s11307-007-0077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghundi M, Fletcher PJ, Drago J, Sibley DR, O'Dowd BF, George SR. Spatial learning deficit in dopamine D(1) receptor knockout mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;383(2):95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghundi M, O'Dowd BF, George SR. Prolonged fear responses in mice lacking dopamine D1 receptor. Brain Res. 2001;892(1):86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry AT, Ongur D, An X, Price JL. Prefrontal cortical projections to the striatum in macaque monkeys: evidence for an organization related to prefrontal networks. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425(3):447–470. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000925)425:3<447::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fibiger HC. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia and mood disorders. In: Willner P, Scheel-Kruger J, editors. The Mesolimbic Dopamine System: From Motivation to Action. New York: Wiley; 1991. pp. 615–638. [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Miyachi S, Paletzki R, Brown P. D1 dopamine receptor supersensitivity in the dopamine-depleted striatum results from a switch in the regulation of ERK1/2/MAP kinase. J Neurosci. 2002;22(12):5042–5054. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05042.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SD, Badalamenti JI. Sex difference in reward asymmetry and effects of cocaine. Neuropharmacology. 1986;25(6):633–637. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(86)90216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SD, Ross DA, Hough LB. Lateral asymmetry of neurotransmitters in human brain. Brain Res. 1982;234(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SD, Weaver LM, Meibach RC. Lateralization of reward in rats: differences in reinforcing thresholds. Science. 1980;207(4435):1093–1095. doi: 10.1126/science.7355277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SD, Weaver LM, Meibach RC. Amphetamine enhancement of reward asymmetry. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1981;73(4):323–327. doi: 10.1007/BF00426459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granon S, Passetti F, Thomas KL, Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Enhanced and impaired attentional performance after infusion of D1 dopaminergic receptor agents into rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20(3):1208–1215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01208.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Kim KS, Mailly P, Calzavara R. Reward-related cortical inputs define a large striatal region in primates that interface with associative cortical connections, providing a substrate for incentive-based learning. J Neurosci. 2006;26(32):8368–8376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0271-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halldin C, Foged C, Chou YH, Karlsson P, Swahn CG, Sandell J, Sedvall G, Farde L. Carbon-11-NNC 112: a radioligand for PET examination of striatal and neocortical D1-dopamine receptors. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(12):2061–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Brit J Med Psychol. 1959:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler G, Fromm S, Carlson PJ, Luckenbaugh DA, Waldeck T, Geraci M, Roiser JP, Neumeister A, Meyers N, Charney DS, Drevets WC. Neural response to catecholamine depletion in unmedicated subjects with major depressive disorder in remission and healthy subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(5):521–531. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen J, Karlsson H, Kajander J, Markkula J, Rasi-Hakala H, Nagren K, Salminen JK, Hietala J. Striatal dopamine D2 receptors in medication-naive patients with major depressive disorder as assessed with [11C]raclopride PET. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197(4):581–590. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Lachowicz JE, Sibley DR. Phenotypic analysis of dopamine receptor knockout mice; recent insights into the functional specificity of dopamine receptor subtypes. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(8):1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Simpson E, Kellendonk C, Kandel ER. Genetic evidence for the bidirectional modulation of synaptic plasticity in the prefrontal cortex by D1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(9):3236–3241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308280101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichise M, Liow JS, Lu JQ, Takano A, Model K, Toyama H, Suhara T, Suzuki K, Innis RB, Carson RE. Linearized reference tissue parametric imaging methods: application to [11C]DASB positron emission tomography studies of the serotonin transporter in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23(9):1096–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000085441.37552.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyo M, Yamasaki T. The detection of age-related decrease of dopamine D1, D2 and serotonin 5-HT2 receptors in living human brain. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1993;17(3):415–421. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(93)90075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med. Image Anal. 2001;5(2):143–156. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karle J, Clemmesen L, Hansen L, Andersen M, Andersen J, Fensbo C, Sloth-Nielsen M, Skrumsager BK, Lublin H, Gerlach J. NNC 01-0687, a selective dopamine D1 receptor antagonist, in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;121(3):328–329. doi: 10.1007/BF02246071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T. Molecular genetics of bipolar disorder and depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61(1):3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimek V, Schenck JE, Han H, Stockmeier CA, Ordway GA. Dopaminergic abnormalities in amygdaloid nuclei in major depression: a postmortem study. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(7):740–748. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimke A, Larisch R, Janz A, Vosberg H, Muller-Gartner HW, Gaebel W. Dopamine D2 receptor binding before and after treatment of major depression measured by [123I]IBZM SPECT. Psychiatry Res. 1999;90(2):91–101. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(99)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koks S, Nikopensius T, Koido K, Maron E, Altmae S, Heinaste E, Vabrit K, Tammekivi V, Hallast P, Kurg A, Shlik J, Vasar V, Metspalu A, Vasar E. Analysis of SNP profiles in patients with major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9(2):167–174. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705005468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo MS, Levitt JJ, Salisbury DF, Nakamura M, Shenton ME, McCarley RW. A cross-sectional and longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study of cingulate gyrus gray matter volume abnormalities in first-episode schizophrenia and first-episode affective psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):746–760. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalumiere RT, Nguyen LT, McGaugh JL. Post-training intrabasolateral amygdala infusions of dopamine modulate consolidation of inhibitory avoidance memory: involvement of noradrenergic and cholinergic systems. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20(10):2804–2810. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert G, Johansson M, Agren H, Friberg P. Reduced brain norepinephrine and dopamine release in treatment-refractory depressive illness: evidence in support of the catecholamine hypothesis of mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(8):787–793. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Huang Y. Vulnerability of positron emission tomography radiotracers to endogenous competition. New insights. Q J Nucl Med. 2001;45(2):124–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Links JM, Zubieta JK, Meltzer CC, Stumpf MJ, Frost JJ. Influence of spatially heterogeneous background activity on "hot object" quantitation in brain emission computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20(4):680–687. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199607000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZH, Shin R, Ikemoto S. Dual Role of Medial A10 Dopamine Neurons in Affective Encoding. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008 doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Soelch C, Infante A, Szczepanik J, Nugent A, Cannon D, Herscovitch P, WC D. Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting Abstract Book. 2007. Lateralized dopaminergic response to reward in the human ventral striatum. [Google Scholar]

- Martinot M, Bragulat V, Artiges E, Dolle F, Hinnen F, Jouvent R, Martinot J. Decreased presynaptic dopamine function in the left caudate of depressed patients with affective flattening and psychomotor retardation. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):314–316. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JH, Kruger S, Wilson AA, Christensen BK, Goulding VS, Schaffer A, Minifie C, Houle S, Hussey D, Kennedy SH. Lower dopamine transporter binding potential in striatum during depression. Neuroreport. 2001;12(18):4121–4125. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112210-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczyk K, Szabatin M, Rudnicki P, Grodzki M, Burger C. A JAVA environment for medical image data analysis: initial application for brain PET quantitation. Med Inform (Lond) 1998;23(3):207–214. doi: 10.3109/14639239809001400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery AJ, Stokes P, Kitamura Y, Grasby PM. Extrastriatal D2 and striatal D2 receptors in depressive illness: pilot PET studies using [11C]FLB 457 and [11C]raclopride. J Affect Disord. 2007;101(1–3):113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery S, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Brit J Psychiat. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(12):1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt DJ, Baldwin DS, Clayton AH, Elgie R, Lecrubier Y, Montejo AL, Papakostas GI, Souery D, Trivedi MH, Tylee A. Consensus statement and research needs: the role of dopamine and norepinephrine in depression and antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 6):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongur D, Ferry AT, Price JL. Architectonic subdivision of the human orbital and medial prefrontal cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460(3):425–449. doi: 10.1002/cne.10609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp M, Klimek V, Willner P. Parallel changes in dopamine D2 receptor binding in limbic forebrain associated with chronic mild stress-induced anhedonia and its reversal by imipramine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;115(4):441–446. doi: 10.1007/BF02245566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsey RV, Oquendo MA, Zea-Ponce Y, Rodenhiser J, Kegeles LS, Pratap M, Cooper TB, Van Heertum R, Mann JJ, Laruelle M. Dopamine D(2) receptor availability and amphetamine-induced dopamine release in unipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(5):313–322. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimoule C, Schoemaker H, Reynolds GP, Langer SZ. [3H]SCH 23390 labeled D1 dopamine receptors are unchanged in schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985;114(2):235–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90634-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW. Chemical neuromodulation of frontal-executive functions in humans and other animals. Exp Brain Res. 2000;133(1):130–138. doi: 10.1007/s002210000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romach MK, Glue P, Kampman K, Kaplan HL, Somer GR, Poole S, Clarke L, Coffin V, Cornish J, O'Brien CP, Sellers EM. Attenuation of the euphoric effects of cocaine by the dopamine D1/D5 antagonist ecopipam (SCH 39166) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(12):1101–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, van der Merwe L, Solms M, Ramesar R. Lateralization of hand skill in bipolar affective disorder. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6(8):698–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Dopamine neurons and their role in reward mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severino G, Congiu D, Serreli C, De Lisa R, Chillotti C, Del Zompo M, Piccardi MP. A48G polymorphism in the D1 receptor genes associated with bipolar I disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;134B(1):37–38. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinotoh H, Inoue O, Hirayama K, Aotsuka A, Asahina M, Suhara T, Yamazaki T, Tateno Y. Dopamine D1 receptors in Parkinson's disease and striatonigral degeneration: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56(5):467–472. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.5.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva MA, Topic B, Lamounier-Zepter V, Huston JP, Tomaz C, Barros M. Evidence for hemispheric specialization in the marmoset (Callithrix penicillata) based on lateralization of behavioral/neurochemical correlations. Brain Res Bull. 2007;74(6):416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifstein M, Kegeles LS, Gonzales R, Frankle WG, Xu X, Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A. [11C]NNC 112 selectivity for dopamine D1 and serotonin 5-HT(2A) receptors: a PET study in healthy human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(10):1733–1741. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhara T, Fukuda H, Inoue O, Itoh T, Suzuki K, Yamasaki T, Tateno Y. Age-related changes in human D1 dopamine receptors measured by positron emission tomography. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;103(1):41–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02244071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhara T, Nakayama K, Inoue O, Fukuda H, Shimizu M, Mori A, Tateno Y. D1 dopamine receptor binding in mood disorders measured by positron emission tomography. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;106(1):14–18. doi: 10.1007/BF02253582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Hatano K, Sakiyama Y, Kawasumi Y, Kato T, Ito K. Age-related changes of dopamine D1-like and D2-like receptor binding in the F344/N rat striatum revealed by positron emission tomography and in vitro receptor autoradiography. Synapse. 2001;41(4):285–293. doi: 10.1002/syn.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Koob GF. Dopamine, schizophrenia, mania, and depression: toward a unified hypothesis of cortico-striato-thalamic function. Behav Brain Sci. 1987;10:197–245. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares JV, Drevets WC, Sahakian BJ. Cognition in mania and depression. Psychol Med. 2003;33(6):959–967. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd RD, Carl J, Harmon S, O'Malley KL, Perlmutter JS. Dynamic changes in striatal dopamine D2 and D3 receptor protein and mRNA in response to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) denervation in baboons. J Neurosci. 1996;16(23):7776–7782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07776.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomer R, Goldstein RZ, Wang GJ, Wong C, Volkow ND. Incentive motivation is associated with striatal dopamine asymmetry. Biol Psychol. 2008;77(1):98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dyck CH, Seibyl JP, Malison RT, Laruelle M, Zoghbi SS, Baldwin RM, Innis RB. Age-related decline in dopamine transporters: analysis of striatal subregions, nonlinear effects, and hemispheric asymmetries. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(1):36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddington JL, Clifford JJ, McNamara FN, Tomiyama K, Koshikawa N, Croke DT. The psychopharmacology-molecular biology interface: exploring the behavioural roles of dopamine receptor subtypes using targeted gene deletion ('knockout') Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001;25(4):925–964. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chan GL, Holden JE, Dobko T, Mak E, Schulzer M, Huser JM, Snow BJ, Ruth TJ, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ. Age-dependent decline of dopamine D1 receptors in human brain: a PET study. Synapse. 1998;30(1):56–61. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199809)30:1<56::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Modulation of memory fields by dopamine D1 receptors in prefrontal cortex. Nature. 1995;376(6541):572–575. doi: 10.1038/376572a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P. Dopaminergic mechanisms in depression and mania. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ, editors. Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. New York: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 921–932. [Google Scholar]

- Willner P. Dopaminergic mechanisms in depression and mania. Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Rompre PP. Brain dopamine and reward. Annu Rev Psychol. 1989;40:191–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RP, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC. Rapid automated algorithm for aligning and reslicing PET images. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16(4):620–633. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199207000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto BK, Lane RF, Freed CR. Normal rats trained to circle show asymmetric caudate dopamine release. Life Sci. 1982;30(25):2155–2162. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YK, Yeh TL, Yao WJ, Lee IH, Chen PS, Chiu NT, Lu RB. Greater availability of dopamine transporters in patients with major depression--a dual-isotope SPECT study. Psychiatry Res. 2008;162(3):230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate CA, Jr, Payne JL, Singh J, Quiroz JA, Luckenbaugh DA, Denicoff KD, Charney DS, Manji HK. Pramipexole for bipolar II depression: a placebo-controlled proof of concept study. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]