Abstract

BACKGROUND

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are essential components of the immune response to fungal pathogens. We examined the role of TLR polymorphisms in conferring a risk of invasive aspergillosis among recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplants.

METHODS

We analyzed 20 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the toll-like receptor 2 gene (TLR2), the toll-like receptor 3 gene (TLR3), the toll-like receptor 4 gene (TLR4), and the toll-like receptor 9 gene (TLR9) in a cohort of 336 recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants and their unrelated donors. The risk of invasive aspergillosis was assessed with the use of multivariate Cox regression analysis. The analysis was replicated in a validation study involving 103 case patients and 263 matched controls who received hematopoietic-cell transplants from related and unrelated donors.

RESULTS

In the discovery study, two donor TLR4 haplotypes (S3 and S4) increased the risk of invasive aspergillosis (adjusted hazard ratio for S3, 2.20; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.14 to 4.25; P = 0.02; adjusted hazard ratio for S4, 6.16; 95% CI, 1.97 to 19.26; P = 0.002). The haplotype S4 was present in carriers of two SNPs in strong linkage disequilibrium (1063 A/G [D299G] and 1363 C/T [T399I]) that influence TLR4 function. In the validation study, donor haplotype S4 also increased the risk of invasive aspergillosis (adjusted odds ratio, 2.49; 95% CI, 1.15 to 5.41; P = 0.02); the association was present in unrelated recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants (odds ratio, 5.00; 95% CI, 1.04 to 24.01; P = 0.04) but not in related recipients (odds ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 0.93 to 5.68; P = 0.07). In the discovery study, seropositivity for cytomegalovirus (CMV) in donors or recipients, donor positivity for S4, or both, as compared with negative results for CMV and S4, were associated with an increase in the 3-year probability of invasive aspergillosis (12% vs. 1%, P = 0.02) and death that was not related to relapse (35% vs. 22%, P = 0.02).

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests an association between the donor TLR4 haplotype S4 and the risk of invasive aspergillosis among recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants from unrelated donors.

Over the past 20 years, invasive aspergillosis has become increasingly frequent among recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplants, with an incidence rate of up to 12%.1 Despite the availability of new azole and echinochandin antifungal drugs, the outcome remains poor, with a 1-year mortality of 50 to 80%, making invasive aspergillosis one of the leading infection-related causes of death among recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplants. 1,2 Identification of patients who are at increased risk for infection before transplantation could facilitate the development of effective prevention strategies.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are transmembrane proteins on the surface of immune cells that detect conserved molecular motifs known as “microbe-associated molecular patterns” from a variety of organisms. They interact with several adapter proteins to activate transcription factors, leading to the production of inflammatory cytokines and the activation of adaptive immunity.3,4 Aspergillus species activate innate immune cells through both toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4).5–10

Common polymorphisms in TLR genes have been associated with susceptibility to several infections.11 Mutations in TLR adapter molecules (i.e., interleukin-1 receptor–associated kinase 4 [IRAK4], inhibitor of nuclear factor κ B kinase γ [IKKγ], and inhibitor of nuclear factor κ B α [IκBα]) cause rare inherited immunodeficiencies, further demonstrating the importance of genetic variability in the TLR signaling pathway.11 In the transplant recipient, inhaled molds may interact with epithelial cells from the recipient or phagocytic cells from the donor lineage; both cells express TLRs. We hypothesized that polymorphisms in TLR genes from the donor and the recipient may influence susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis in recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the frequencies of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for four candidate TLR genes in a cohort of recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants and unrelated donors.

METHODS

PATIENTS

All patients who received an allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplant from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance between 1989 and 2004 were eligible for this analysis. Specimens were obtained and DNA was extracted by our Human Immunogenetics Program in an ongoing process that was based solely on the availability of specimens, and no preferences were given to any specific clinical variables. For the discovery and validation studies, patients were selected sequentially from the overall pool of specimens available at the time the respective studies were conducted, and no patient was included in both studies.

For the discovery study, we identified 374 patients with available DNA who underwent their first allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation from an unrelated donor between 1995 and 2003. Cases were identified from microbiologic and histopathological reports in clinical charts and classified as “probable” or “proven” invasive aspergillosis, with the use of definitions developed by the Mycoses Study Group of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer.12 Among the 374 patients, 38 were excluded for one or more of the following reasons: both the donor and recipient had a nonwhite or unknown race or ethnic group (32 patients), invasive aspergillosis occurred before the first or after a second transplantation (5), the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis was classified as “possible” (3), and infection was due to an invasive mold other than aspergillus species (2).

For the validation study, we used a matched case–control design and included recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants from related donors. A minimal number of 100 cases with at least one matched control was required for odd ratios of approximately 2.3, 2.0, and 1.8, with 80% power and a 5% type I error rate, for allelic frequencies of 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively (calculated with the use of Quanto 1.2.3 software).13 Among the 223 patients in whom invasive aspergillosis occurred between 1989 and 2004, identified from the overall pool from the Human Immunogenetics Program, 120 patients were excluded for one of the following reasons: the donor had an unknown or a nonwhite race or ethnic group (67 patients), invasive aspergillosis occurred before the first or after a second transplantation (37), or the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis was classified as “possible” (16). For each of the 103 remaining patients with invasive aspergillosis, 1 to 6 controls were matched according to age (<40 or ≥40 years), donor race or ethnic group, donor type, and year of transplantation (±5 years). Among 404 selected controls, 263 had available DNA and were included in the validation study. A subgroup analysis was performed to account for differences in the types of hematopoietic-cell transplants.

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease were diagnosed according to standard definitions.14–16 All patients received systemic antibiotic prophylaxis during the period of neutropenia, as well as prophylactic acyclovir, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole or dapsone, and fluconazole, until day 75 after hematopoietic-cell transplantation. A small number of patients (35 patients in the discovery study and 13 in the validation study) received itraconazole or voriconazole prophylaxis on the basis of the individual physician’s decision or as part of a prospective, randomized study of the efficacy of itraconazole versus fluconazole prophylaxis.17

Patients and donors gave written informed consent for data collection, cell storage, and cryo-preservation. Batched genotyping was performed according to protocols approved by the institutional review board of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. The study was also approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (Olympia, WA).

SINGLE-NUCLEOTIDE POLYMORPHISMS

Previously identified minimal haplotype-tagging SNPs from the Innate Immunity Program in Genomic Applications database (http://innateimmunity.net/) were used for each candidate gene. Five additional SNPs that have previously been reported to be associated with human diseases were also genotyped. A total of 20 SNPs in TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR9 were identified with the use of a mass-spectrometry genotyping platform (Sequenom).18

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and pairwise linkage disequilibrium were calculated with the use of the genwh and pwld programs developed in Stata software, version 9.2 (StataCorp). We considered an R2 value of more than 0.90 to represent strong linkage disequilibrium. Haplotypes were inferred with the use of the expectation-maximization algorithm implemented in the Decipher program (SAGE).19 We grouped all rare haplotypes (frequencies <2%) into one group for each gene. All analyses were performed for white donors, white recipients, or both; race was reported by the donors and recipients.

The probability of invasive aspergillosis according to TLR variants at 6 and 36 months after transplantation was estimated with the use of cumulative incidence curves, with censoring of data at the date of the last follow-up and with death, second transplantation, and morphologic relapse treated as competing risks.20 A period of 36 months was chosen because all cases of invasive aspergillosis in the discovery cohort had occurred during this period, and a period of 6 months was chosen in order to assess early invasive aspergillosis. Comparisons of the risks of invasive aspergillosis and death on the basis of the TLR variants were performed with the use of univariate Cox regression models, unless otherwise specified. Multivariate Cox models were used to evaluate the relative hazards associated with TLR variants. Candidate covariates were selected from the factors associated with aspergillosis or death in the univariate analysis (P≤0.15) or in previous studies.1 The covariates were entered one by one in a pairwise model together with the significant TLR variant and kept in the final model if they remained significant (P<0.05) or altered the association with the TLR variant by more than 10%. Conditional logistic regression was used in the analysis of the data from the case–control validation study, with the use of similar methods for selecting variables.

Because of the large number of statistical comparisons made in the discovery study, the P values presented should be interpreted cautiously. To facilitate this interpretation, we report P values that would remain significant with the application of traditional Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons. Among the 20 SNPs tested, two pairs of SNPs were found to be in strong linkage disequilibrium: TLR4 1063 A/G and TLR4 1363 C/T (R2 = 0.96), and TLR9 +1174 G/A and TLR9 1635 A/G (R2 = 0.96); these findings are consistent with previous observations.21,22 Since the analyses for these SNPs are redundant, 18 independent tests were considered for multiple-testing correction. For haplotypes, we considered four independent tests (i.e., one for each gene). Since the case–control study was performed for validation and was limited to TLR4, no correction for multiple testing was applied in this study.

RESULTS

DISCOVERY STUDY

The discovery study included 336 patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation after a myeloablative-conditioning regimen (Table 1). The median follow-up time among patients who survived was 84 months (range, 5 to 124). Among the 336 patients, 33 had proven or probable invasive aspergillosis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Transplant Donors and Recipients in the Discovery and Validation Studies.*

| Variable | Discovery Study | Validation Study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive Aspergillosis (N = 33) |

No Invasive Aspergillosis (N = 303) |

P Value† | Invasive Aspergillosis (N = 33) |

No Invasive Aspergillosis (N = 303) |

P Value† | |

| Race of donor and recipient — % | ||||||

| White/white | 55 | 67 | 98 | 99 | ||

| White/other‡ | 39 | 27 | ||||

| Other/white‡ | 6 | 6 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Age — yr* | ||||||

| <40 yr | 58 | 54 | 34 | 34 | ||

| ≥40 yr | 42 | 46 | 0.84 | 66 | 66 | |

| Sex of donor and recipient — % | ||||||

| Male/male | 36 | 40 | 43 | 35 | ||

| Male/female | 27 | 23 | 0.57 | 28 | 25 | 0.65 |

| Female/male | 21 | 19 | 0.63 | 15 | 25 | 0.05 |

| Female/female | 15 | 17 | 0.92 | 15 | 16 | 0.51 |

| Transplantation type — %* | ||||||

| Matched, related | 52 | 57 | ||||

| Mismatched, related | 16 | 19 | ||||

| Matched, unrelated | 58 | 65 | 20 | 15 | ||

| Mismatched, unrelated | 42 | 35 | 0.31 | 13 | 9 | |

| Underlying disease — % | ||||||

| CML, chronic phase | 36 | 40 | 21 | 30 | ||

| Hematologic cancer | ||||||

| First remission | 52 | 45 | 0.32 | 61 | 57 | 0.03 |

| Subsequent remission or relapse | 9 | 13 | 0.73 | 18 | 13 | 0.03 |

| Other disease§ | 3 | 2 | 0.61 | |||

| Myeloablative-conditioning regimen — % | ||||||

| With TBI | 82 | 86 | 64 | 56 | ||

| Without TBI | 18 | 14 | 0.55 | 36 | 44 | 0.35 |

| Graft source — % | ||||||

| Bone marrow cells¶∥ | 94 | 94 | 85 | 87 | ||

| Peripheral-blood cells | 6 | 6 | 0.97 | 15 | 13 | 0.26 |

| CMV serostatus of donor and recipient — % | ||||||

| CMV-negative/CMV-negative | 24 | 46 | 25 | 37 | ||

| CMV-negative/CMV-positive, CMV-positive/CMV-positive, or CMV-positive/CMV-negative | 76 | 54 | 0.01 | 75 | 63 | 0.06 |

| GVHD prophylaxis containing anti–T-cell therapy — % | 9 | 8 | 0.92 | 12 | 10 | 0.46 |

| GVHD — %∥ | ||||||

| Acute (grade III or IV), cumulative incidence at day 80 | 96 | 35 | <0.001 | 46 | 25 | <0.001 |

| Chronic extensive, cumulative incidence at day 300 | 57 | 68 | 0.04 | 17 | 13 | 0.12 |

| CMV disease, cumulative incidence at day 150 — %∥ | 12 | 4 | 0.08 | 8 | 2 | 0.01 |

| Invasive aspergillosis — no. (%) | ||||||

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Proven | 16 (48) | 61 (59) | ||||

| Probable | 17 (52) | 42 (41) | ||||

| Localization | ||||||

| Pulmonary | 20 (61) | 77 (75) | ||||

| Disseminated | 7 (21) | 21 (20) | ||||

| Sinus | 3 (9) | 5 (5) | ||||

| Other** | 3 (9) | |||||

| Microbiologic findings | ||||||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 22 (67) | 56 (54) | ||||

| A. niger | 3 (9) | 1 (1) | ||||

| A. flavus | 1 (3) | 4 (4) | ||||

| Aspergillus species | 3 (9) | 3 (3) | ||||

| Mixed infections with aspergillus species | 2 (6) | 14 (14) | ||||

| Culture negative | 2 (6) | 25 (24) | ||||

| Median time from transplantation to diagnosis — days (range) | 100 (11–732) | 68 (4–1384)†† | ||||

Controls in the case–control study were matched according to age, type of transplantation, and year of transplantation. CML denotes chronic myeloid leukemia, CMV cytomegalovirus, GVHD graft-versus-host disease, and TBI total-body irradiation.

P values are for univariate Cox regression models.

Data on the race of the donor were missing in 94 cases. Race was self-reported.

Other diseases included aplastic anemia (in five patients), paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (in one), and idiopathic thrombocytopenia (in one).

One patient with invasive aspergillosis in the discovery study underwent transplantation of cord-blood cells.

In the case–control study, numbers indicate the percentage of patients with acute or chronic GVHD and CMV disease before the occurrence of invasive aspergillosis in case patients and during the corresponding period in matched controls.

This category includes the central nervous system (in two patients) and the mouth (in one).

The median time to invasive aspergillosis was 71 days in recipients of transplants from unrelated donors and 68 days in recipients of transplants from related donors.

UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS

To assess the risk of invasive aspergillosis according to TLR SNPs and haplotypes in recipients and donors of hematopoietic-cell transplants, we estimated the cumulative incidence of infection 6 months and 36 months after hematopoietic-cell transplantation. Two SNPs in donors of hematopoietic-cell transplants (1063 A/G [D299G] and 1363 C/T [T399I]), which were in strong linkage disequilibrium (R2=0.96), influenced the risk of the development of invasive aspergillosis (see Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at www.nejm.org). The association was stronger at 6 months (for TLR4 1363T, the cumulative incidence of invasive aspergillosis was 22% in the presence of the allele vs. 5% in its absence; P = 0.002) (Table 2) and remained significant after correction for multiple testing (P = 0.03). Another donor SNP in TLR4, −2604G, tended to influence the risk of invasive aspergillosis when the comparison was made at 36 months (cumulative incidence of invasive aspergillosis, 4% in the presence of the allele vs. 13% in its absence; P = 0.01), but the association was no longer present when correction for multiple testing was applied (P = 0.20).

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of the Association of Donor TLR4 Polymorphisms with the Cumulative Incidence of Invasive Aspergillosis in the Discovery Study.*

| Donor Polymorphism (Amino Acid Change) |

Cumulative Incidence of Invasive Aspergillosis at 6 Mo (N = 242) |

Cumulative Incidence of Invasive Aspergillosis at 36 Mo (N = 242) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Absent | Variant Present | P Value† | Variant Absent | Variant Present | P Value† | |

| % | % | |||||

| Single-nucleotide polymorphisms | ||||||

| TLR4 −3612 A/G (−) | 8 | 6 | 0.62 | 11 | 6 | 0.18 |

| TLR4 −2604 A/G (−) | 4 | 10 | 0.06 | 4 | 13 | 0.01 |

| TLR4 −1607 T/C (−) | 7 | 4 | 0.41 | 7 | 11 | 0.34 |

| TLR4 1363 C/T (T399I) | 5 | 22 | 0.002‡ | 7 | 22 | 0.01 |

| TLR4 +11381 G/C (−) | 8 | 4 | 0.34 | 10 | 4 | 0.14 |

| TLR4 +12186 G/C (−) | 8 | 5 | 0.41 | 10 | 5 | 0.20 |

| Haplotypes | ||||||

| TLR4 S1 | 3 | 7 | 0.42 | 13 | 8 | 0.35 |

| TLR4 S2§ | 8 | 4 | 0.39 | 10 | 4 | 0.18 |

| TLR4 S3 | 6 | 9 | 0.36 | 6 | 17 | 0.01‡ |

| TLR4 S4¶ | 5 | 22 | 0.002‡ | 7 | 22 | 0.01‡ |

Since 94 of 336 donors were not white or data on race were missing, the denominator in the cohort study was 242 donors. Simplified TLR4 haplotypes are indicated by the letter S (for three-locus haplotypes).

P values were calculated with the use of the log-rank test.

After adjustment for multiple testing with the use of the Bonferroni method in the discovery study, P=0.0028 for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (on the basis of 18 independent tests) and P = 0.0125 for haplotypes (on the basis of 4 independent tests).

The S2 haplotype was present in persons carrying the minor alleles of SNPs +12186 G/C.

The S4 haplotype was present in persons carrying the minor alleles of SNPs 1063 A/G and 1363 C/T (both in strong linkage disequilibrium, R2 = 0.96).

Three TLR4 haplotypes in donors (H5, H6, and H8) were or tended to be associated with an increased risk of invasive aspergillosis (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Since these three haplotypes included −2604G and +12186G carriers, and H6 also included 1363T carriers, a three-locus haplotype was created (Fig. 1D). Haplotypes S3 and S4 influenced the risk of the development of invasive aspergillosis. For S3, the association was present only at 36 months (17% in its presence vs. 6% in its absence, P = 0.01; P = 0.04 with adjustment for multiple testing); for S4, a haplotype that included 1363T carriers, the association was stronger at 6 months (22% vs. 5%, P = 0.002; P = 0.03 with adjustment for multiple testing).

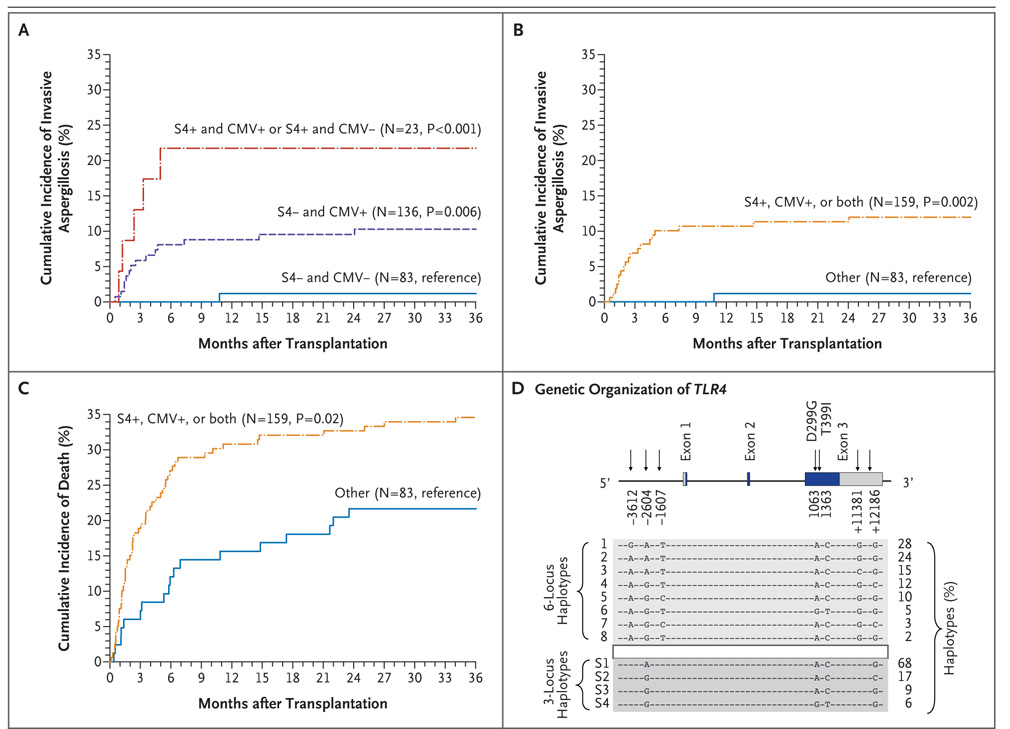

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Invasive Aspergillosis and Death after Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation, According to Donor TLR4 Haplotype Status and CMV Serostatus in the Discovery Study.

In Panels A, B, and C, the end point was the time to the diagnosis of proven or probable invasive aspergillosis in 242 eligible patients, with censoring of the data for these patients at the date of last follow-up. Relapsed malignant condition, subsequent hematopoietic-cell transplantation, and death were considered to be competing risks. P values were calculated with the use of the log-rank test. Since both cytomegalovirus (CMV) serostatus and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) haplotypes can be assessed before hematopoietic-cell transplantation, the cumulative incidences were stratified according to CMV serostatus (CMV− denotes CMV-negative donors and CMV-negative recipients) versus the other patients (CMV+ denotes CMV-negative donors and CMV-positive recipients, CMV-positive donors and CMV-positive recipients, and CMV-positive donors and CMV-negative recipients) and the presence or absence of donor S4 ( S4+ or S4−). In Panel D, haplotypes were inferred for white donors and recipients together with the use of SAGE software. TLR4 1063 A/G and 1363 C/T are in strong linkage disequilibrium and can be used interchangeably within the six-locus and three-locus haplotypes. Data are based on reference sequences NM_138554, NT_008470, and NP_612564. Rare haplotypes (frequency <2%) are not represented.

MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS

The final SNP model included TLR4 −2604G (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02 to 10.16; P = 0.05) (Table 3) and 1363T (adjusted hazard ratio, 4.96; 95% CI, 1.52 to 16.24; P = 0.008). In the final haplotype model, the hazard ratio for S3 was 2.20 (95% CI, 1.14 to 4.25; P = 0.02) and the hazard ratio for S4 was 6.16 (95% CI, 1.97 to 19.26; P = 0.002). Both final models also included seropositivity for CMV in the patient, the donor, or both (hazard ratio, 4.90; 95% CI, 1.51 to 15.91; P = 0.008) and acute GVHD (hazard ratio, 3.11; 95% CI, 1.22 to 7.90; P = 0.02) in the haplotype model, indicating that donor S4 (or TLR4 1363T), CMV seropositivity, and acute GVHD were independent risk factors for invasive aspergillosis. The interaction between positivity for CMV and S4 did not influence the risk of invasive aspergillosis (P = 0.23).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analyses of the Association of Donor TLR4 Polymorphisms with the Risk of Invasive Aspergillosis in Both Studies.*

| Variable | Discovery Study, Unrelated Donors (N = 242) |

Validation Study, All Donors (N = 366) |

Validation Study, Unrelated Donors (N = 97) |

Validation Study, Related Donors (N = 269) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI)† |

P Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)‡ |

P Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)‡ |

P Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)‡ |

P Value | |

| Model using donor SNPs (amino acid change) | ||||||||

| TLR4 −2604 A/G (−) | 3.22 (1.02–10.16) | 0.05 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| TLR4 1363 C/T (T399I) | 4.96 (1.52–16.24) | 0.008§ | 2.63 (1.19–5.84) | 0.02 | 4.57 (1.00–21.01) | 0.05 | 2.48 (0.95–6.45) | 0.06 |

| TLR4 +12186 G/C (−) | NA | 2.00 (1.14–3.49) | 0.02 | NA | 2.18 (1.13–4.21) | 0.02 | ||

| Model using simplified donor haplotypes | ||||||||

| TLR4 S1 | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||

| TLR4 S2¶ | 0.65 (0.19–2.23) | 0.49 | 1.74 (1.04–2.93) | 0.04 | 1.13 (0.45–2.84) | 0.79 | 1.86 (1.01–3.44) | 0.05 |

| TLR4 S3 | 2.20 (1.14–4.25) | 0.02 | 0.64 (0.30–1.34) | 0.23 | 1.32 (0.41–4.17) | 0.64 | 0.42 (0.15–1.15) | 0.09 |

| TLR4 S4∥ | 6.16 (1.97–19.26) | 0.002§ | 2.49 (1.15–5.41) | 0.02** | 5.00 (1.04–24.01) | 0.04 | 2.29 (0.93–5.68) | 0.07 |

Results are for multivariate Cox regression models in the discovery study and conditional logistic regressions in the validation study. Hazard ratios and odd ratios are for the presence versus the absence of the minor allele. Simplified TLR4 haplotypes are indicated by the letter S (for three-locus haplotypes). CMV denotes cytomegalovirus, GVHD graft-versus-host disease, NA not applicable, SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, and TLR toll-like receptor.

Hazard ratios and odds ratios have been adjusted for CMV serostatus in the donor, recipient, or both and for the presence or absence of acute GVHD (as a time-dependent covariate in the discovery study, during the time from transplantation to the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in case patients from the case–control study, and during the corresponding time in matched controls).

Odds ratios have been adjusted for the underlying disease, the use or nonuse of antifungal prophylaxis (itraconazole or voriconazole), and the sex of the donor and recipient. The model was also adjusted for acute and chronic GVHD, as well as CMV disease, during the time from transplantation to the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in cases and during the corresponding time in matched controls.

After adjustment for multiple testing with the use of the Bonferroni method in the discovery study, P = 0.028 for SNPs (on the basis of 18 independent tests) and P=0.0125 for haplotypes (on the basis of 4 independent tests).

The S2 haplotype was present in persons carrying the minor alleles of SNPs +12186 G/C.

The S4 haplotype was present in persons carrying the minor alleles of SNPs 1063 A/G and 1363 C/T (both in strong linkage disequilibrium, R2 = 0.96).

A subgroup analysis was performed to allow for a comparison among types of hematopoietic-cell transplants in the discovery and validation studies.

VALIDATION STUDY

The characteristics of the patients in the case–control study were similar to those of the patients in the initial study (Table 1), but the validation study included recipients of transplants from both related and unrelated donors, and the median time to invasive aspergillosis after transplantation was shorter (68 days vs. 100 days). The association of donor TLR4 S4 with the risk of invasive aspergillosis was confirmed in the validation study (adjusted odds ratio, 2.49; 95% CI, 1.15 to 5.41; P = 0.02) (Table 3). In the subgroup analysis, the association between S4 and invasive aspergillosis was significant among recipients of transplants from unrelated donors (adjusted odds ratio, 5.00; 95% CI, 1.04 to 24.01; P = 0.04) (Table 3) but not among recipients of transplants from related donors (adjusted odds ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 0.93 to 5.68; P = 0.07). No association between S3 and invasive aspergillosis was observed in the validation study. However, in this group, haplotype S2 tended to increase the risk of invasive aspergillosis (adjusted odds ratio, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.01 to 3.44; P = 0.05); this haplotype was present in TLR4 +12186G carriers, and this allele also increased the risk of invasive aspergillosis in the SNP model (adjusted odds ratio, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.13 to 4.21; P = 0.02).

RISK ASSESSMENT BEFORE HEMATOPOIETIC-CELL TRANSPLANTATION

Since CMV serologic testing and TLR4 haplotype analysis can both be used before hematopoietic-cell transplantation to evaluate the risk of invasive aspergillosis and death, patients were stratified into groups according to CMV serologic status (CMV-negative vs. CMV-positive) and status with respect to donor haplotype S4 (S4-negative vs. S4-positive) (Fig. 1). In the discovery study, invasive aspergillosis occurred in 1 of 83 CMV-negative and S4-negative patients (1%), 14 of 136 CMV-positive and S4-negative patients (10%), and 5 of 23 CMV-negative and S4-positive or CMV-positive and S4-positive patients (22%) (Fig. 1A). Since the number of patients in some groups was small, all patients who were CMV-positive, S4-positive, or both were grouped together (Fig. 1B and 1C). The cumulative incidence of invasive aspergillosis increased from 1% in 83 CMV-negative and S4-negative patients to 12% in 159 patients who were CMV-positive, S4-positive, or both (hazard ratio, 11.95; 95% CI, 1.60 to 89.34; P = 0.02, after adjustment for pretransplantation covariates). The cumulative incidence of death not related to relapse increased from 22% among CMV-negative and S4-negative patients to 35% among patients who were CMV-positive, S4-positive, or both (hazard ratio, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.10 to 3.20; P = 0.02, after adjustment for pretransplantation covariates) (Table 4). In the validation study, the odds ratio for invasive aspergillosis among patients who were CMV-positive and S4-positive or CMV-negative and S4-positive, as compared with those who were CMV-negative and S4-negative, was 3.10 (95% CI, 1.29 to 7.45; P = 0.01), and for patients who were CMV-positive and S4-negative, the odds ratio was 1.54 (95% CI, 0.84 to 2.85; P = 0.16), after adjustment for pretrans-plantation and post-transplantation covariates.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis of Pretransplantation Risk Factors for Death Not Related to Relapse in the Discovery Study.

| Variable | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| CMV seropositivity, S4 positivity, or both* | 1.88 (1.10–3.20) | 0.02 |

| Underlying disease | ||

| CML, chronic phase | Reference group | |

| Hematologic cancer | ||

| First remission | 1.60 (0.98–2.61) | 0.06 |

| Subsequent remission or relapse | 0.55 (0.19–1.59) | 0.27 |

| Other underlying disease | 1.11 (0.26–4.67) | 0.89 |

CMV seropositivity refers to the presence of positive serologic findings in the donor or recipient of a hematopoietic-cell transplant, and S4 positivity refers to the presence of the TLR4 S4 haplotype in the donor of a hematopoietic-cell transplant. CML denotes chronic myeloid leukemia, and CMV cytomegalovirus.

DISCUSSION

These data suggest an association between the TLR4 haplotype S4 in donors of hematopoietic-cell transplants (haplotype frequency, 6%) and invasive aspergillosis in recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants. This haplotype was present in carriers of two SNPs in strong linkage disequilibrium (1063G and 1363T) that influence TLR4 function.

The TLR genes were initially identified through their homology with the Toll gene in Drosophila melanogaster, which triggers the production of drosomycin and is required for effective protection against fungal infections.23 Mammalian TLR4 was first recognized as the transmembrane receptor for lipopolysaccharide, a key component for the detection of gram-negative bacteria.24 Subsequent studies have shown that TLR4 is also involved in the recognition of fungal ligands, including mannan (derived from Candida albicans)25 and glucuron-oxylomannan (derived from Cryptococcus neoformans).26 Several studies have highlighted the role of TLR2 and TLR4 in the innate immune recognition of aspergillus species.5–10 Although TLR2-dependent responses have been shown to augment β-1,3 glucan stimulation through dectin-1, the microbial Aspergillus fumigatus TLR2 and TLR4 ligands have not yet been identified.9

TLR4 1063G and 1363T SNPs have been reported to be associated with susceptibility to infections caused by gram-negative bacteria,27,28 C. albicans,29 brucella species,30 respiratory syncytial virus,31 and Plasmodium falciparum.32 Persons who are heterozygous for the 1063G and 1363T SNPs are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide, as measured by the bronchospastic response after inhalation of endotoxin.33 Furthermore, airway epithelial cells isolated from heterozygous persons were reported to have a deficient response to lipopolysaccharide, suggesting that 1063G and 1363T act in a dominant fashion with respect to the wild-type allele.33 However, monocytes and whole blood isolated from heterozygous subjects did not have abnormal responses to lipopolysaccharide, 34,35 suggesting that the effects of these polymorphisms may vary among cell types or experimenta l conditions or that polymorphisms other than 1063G and 1363T interfere with the results.

A possible limitation of this study is the fact that genetic associations can be biased by population stratification.36 However, we observed a similar association in two separate studies, suggesting that a confounding effect is unlikely. Another limitation is the possibility that TLR4 SNPs and haplotypes associated with invasive aspergillosis are in linkage disequilibrium with SNPs in another gene, located nearby, that are responsible for the alterations in the phenotype. However, the fact that TLR4 is an essential receptor for aspergillus species and that TLR4 1063 A/G and 1363 C/T SNPs impair TLR4 function suggests that the polymorphisms in TLR4 are probably responsible for the observed phenotypes. Finally, polymorphisms may not be directly associated with invasive aspergillosis, but instead may be associated with other factors, such as acute GVHD or CMV seropositivity, that also influence the end point.37,38 However, this possibility is unlikely, given the multivariate analysis, which identified donor S4, acute GVHD, and CMV seropositivity as three independent risk factors.

Polymorphisms in genes encoding interleukin-10, tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2, TLR1, and TLR6 have previously been shown to influence susceptibility to various clinical forms of aspergillosis.39–43 However, the TLR4 polymorphisms that we found to be significantly associated with invasive aspergillosis were derived from donor cells in hematopoietic-cell transplants, not from recipient cells. Thus, patients who undergo hematopoietic-cell transplantation are chimeras for whom the immune system is derived in part from the recipient (e.g., epithelial cells) and in part from the donor (hematopoietic cells). Polymorphisms in TLR genes expressed on the surface of polymorphonuclear neutrophils10 or resident macrophages, which are from the donor’s cell lineage, may impair cellular activation and antifungal responses.

The association of S4 with an increased risk of invasive aspergillosis, observed in the discovery study, was also observed in the validation study, which included recipients of transplants from related donors and from unrelated donors. In the subgroup analysis, the association was present among the patients who received transplants from unrelated donors, as it was in the discovery study, but it was not present among the recipients of transplants from related donors. The reason for these differences is unknown. They may result from differences in the level of immunosuppression between recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants from related donors and recipients of transplants from unrelated donors, or they may be explained by the relatively small size of the groups after stratification. In any case, these findings should be interpreted in the context of the limitations of subgroup analyses.44 Further studies will be needed to clarify this issue.

In conclusion, this study suggests an association between TLR4 haplotypes in unrelated donors and an increased risk of invasive aspergillosis among recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplants. The identification of donors who have an increased risk of severe infection may have implications for prevention strategies in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplants.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Swiss Foundation for Medical and Biological Grants (1121), the Swiss National Science Foundation (81LA-65462), and the Leenaards Foundation (to Dr. Bochud); and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (CA18029, CA15704, AI054523, AI051468, AI33484, HL87690, HL088201, and HL69860). Some of the results of this study were obtained with the use of SAGE software, which is supported by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources (RR03655).

Dr. Marr reports receiving consulting fees from Astellas, Basilea, Enzon, Merck, Pfizer, and Schering-Plough, being a member of a data and safety monitoring board for a trial of antifungal prophylaxis for Schering-Plough, and receiving research support from Astellas, Pfizer, Enzon, and Merck; Dr. Boeckh, being a member of a data and safety monitoring board for a human immunodeficiency virus trial for Pfizer, receiving research support from Pfizer and Merck, and receiving consulting fees from Enzon; and Drs. Bochud, Boeckh, Chien, and Marr, having a pending application for a patent on TLR4 SNPs and haplotypes and the risk of aspergillosis. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

We thank Jeremy Smith, Ravinder K. Sandhu, Craig Silva, Christopher Davis, Peter Choe, and Sanam Hussain for assistance in data collection and handling; Jeffrey Stevens, Gary J. Olsem, Tera R. Matson, Terry Stevens-Ayers, Jennifer Gravley, and Kimberly Harrington for technical assistance; and Véronique Erard for critical review of an earlier version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

POSTING PRESENTATIONS AT MEDICAL MEETINGS ON THE INTERNET

Posting an audio recording of an oral presentation at a medical meeting on the Internet, with selected slides from the presentation, will not be considered prior publication. This will allow students and physicians who are unable to attend the meeting to hear the presentation and view the slides. If there are any questions about this policy, authors should feel free to call the Journal’s Editorial Offices.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marr KA, Carter RA, Crippa F, Wald A, Corey L. Epidemiology and outcome of mould infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:909–917. doi: 10.1086/339202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:531–540. doi: 10.1086/510592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beutler B. Inferences, questions and possibilities in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature. 2004;430:257–263. doi: 10.1038/nature02761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braedel S, Radsak M, Einsele H, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus antigens activate innate immune cells via toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Br J Haematol. 2004;125:392–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mambula SS, Sau K, Henneke P, Golenbock DT, Levitz SM. Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling in response to Aspergillus fumigatus. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39320–39326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meier A, Kirschning CJ, Nikolaus T, Wagner H, Heesemann J, Ebel F. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 are essential for Aspergillus-induced activation of murine macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:561–570. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Netea MG, Warris A, Van der Meer JW, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus evades immune recognition during germination through loss of toll-like receptor-4-mediated signal transduction. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:320–326. doi: 10.1086/376456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gersuk GM, Underhill DM, Zhu L, Marr KA. Dectin-1 and TLRs permit macrophages to distinguish between different Aspergillus fumigatus cellular states. J Immunol. 2006;176:3717–3724. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellocchio S, Moretti S, Perruccio K, et al. TLRs govern neutrophil activity in aspergillosis. J Immunol. 2004;173:7406–7415. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bochud PY, Bochud M, Telenti A, Calandra T. Innate immunogenetics: a tool for exploring new frontiers of host defence. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:531–542. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70185-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ascioglu S, Rex JH, de Pauw B, et al. Defining opportunistic invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplants: an international consensus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:7–14. doi: 10.1086/323335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauderman WJ, Morrison JM. QUAN-TO 1.1: a computer program for power and sample size calculations for genetic-epidemiology studies. (Available at http://hydra.usc.edu/gxe/.)

- 14.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan KM, Agura E, Anasetti C, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease and other late complications of bone marrow transplantation. Semin Hematol. 1991;28:250–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ljungman P, Griffiths P, Paya C. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1094–1097. doi: 10.1086/339329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marr KA, Crippa F, Leisenring W, et al. Itraconazole versus fluconazole for prevention of fungal infections in patients receiving allogeneic stem cell transplants. Blood. 2004;103:1527–1533. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bochud PY, Hersberger M, Taffé P, et al. Polymorphisms in Toll-like receptor 9 influence the clinical course of HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2007;21:441–446. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328012b8ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.S.A.G.E. (Statistical Analysis for Genetic Epidemiology) version 5.0. Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalbfleisch JP, Prentice RL. The statistical analysis of failure time data. New York: John Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiechl S, Lorenz E, Reindl M, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphisms and atherogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:185–192. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazarus R, Klimecki WT, Raby BA, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the Toll-like receptor 9 gene (TLR9): frequencies, pairwise linkage disequilibrium, and haplotypes in three U.S. ethnic groups and exploratory case-control disease association studies. Genomics. 2003;81:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(02)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. The dorso-ventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86:973–983. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Netea MG, Gow NA, Munro CA, et al. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1642–1650. doi: 10.1172/JCI27114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shoham S, Huang C, Chen JM, Golenbock DT, Levitz SM. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates intracellular signaling without TNF-alpha release in response to Cryptococcus neoformans polysaccharide capsule. J Immunol. 2001;166:4620–4626. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agnese DM, Calvano JE, Hahm SJ, et al. Human toll-like receptor 4 mutations but not CD14 polymorphisms are associated with an increased risk of gram-negative infections. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1522–1525. doi: 10.1086/344893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorenz E, Mira JP, Frees KL, Schwartz DA. Relevance of mutations in the TLR4 receptor in patients with gram-negative septic shock. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1028–1032. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.9.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van der Graaf CA, Netea MG, Morré SA, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 Asp299Gly/Thr399Ile polymorphisms are a risk factor for Candida bloodstream infection. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rezazadeh M, Hajilooi M, Rafiei A, et al. TLR4 polymorphism in Iranian patients with brucellosis. J Infect. 2006;53:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tal G, Mandelberg A, Dalal I, et al. Association between common Toll-like receptor 4 mutations and severe respiratory syncytial virus disease. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:2057–2063. doi: 10.1086/420830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mockenhaupt FP, Cramer JP, Hamann L, et al. Toll-like receptor (TLR) polymorphisms in African children: common TLR-4 variants predispose to severe malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:177–182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506803102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arbour NC, Lorenz E, Schutte BC, et al. TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nat Genet. 2000;25:187–191. doi: 10.1038/76048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Aulock S, Schroder NW, Gueinzius K, et al. Heterozygous toll-like receptor 4 polymorphism does not influence lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine release in human whole blood. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:938–943. doi: 10.1086/378095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erridge C, Stewart J, Poxton IR. Monocytes heterozygous for the Asp299Gly and Thr399Ile mutations in the Toll-like receptor 4 gene show no deficit in lipopolysaccharide signalling. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1787–1791. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wacholder S, Rothman N, Caporaso N. Counterpoint: bias from population stratification is not a major threat to the validity of conclusions from epidemiological studies of common polymorphisms and cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:513–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin MT, Storer B, Martin PJ, et al. Relation of an interleukin-10 promoter polymorphism to graft-versus-host disease and survival after hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2201–2210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin MT, Storer B, Martin PJ, et al. Genetic variation in the IL-10 pathway modulates severity of acute graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic cell transplantation: synergism between IL-10 genotype of patient and IL-10 receptor beta genotype of donor. Blood. 2005;106:3995–4001. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seo KW, Kim DH, Sohn SK, et al. Protective role of interleukin-10 promoter gene polymorphism in the pathogenesis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:1089–1095. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sainz J, Hassan L, Perez E, et al. Interleukin-10 promoter polymorphism as risk factor to develop invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Immunol Lett. 2007;109:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sainz J, Perez E, Hassan L, et al. Variable number of tandem repeats of TNF receptor type 2 promoter as genetic biomarker of susceptibility to develop invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Hum Immunol. 2007;68:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kesh S, Mensah NY, Peterlongo P, et al. TLR1 and TLR6 polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1062:95–103. doi: 10.1196/annals.1358.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaid M, Kaur S, Sambatakou H, Madan T, Denning DW, Sarma PU. Distinct alleles of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) and surfactant proteins A (SP-A) in patients with chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:183–186. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM. Statistics in medicine — reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2189–2194. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr077003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]