Abstract

The purpose of this assessment is to increase our understanding of how safety and environmental factors influence physical activity among African American residents living in a low-income, high-crime neighborhood and to get input from these residents about how to best design physical activity interventions for their neighborhood. Twenty-seven African American adult residents of a low-income, high-crime neighborhood in a suburban southeastern community participated in three focus groups. Participants were asked questions about perceptions of what would help them, their families, and their neighbors be more physically active. Two independent raters coded the responses into themes. Participants suggested three environmental approaches in an effort to increase physical activity: increasing law enforcement, community connectedness and social support, and structured programs. Findings suggest that safety issues are an important factor for residents living in disadvantaged conditions and that the residents know how they want to make their neighborhoods healthier.

Keywords: assessment, environment, safety, community solutions, physical activity

Residents of more disadvantaged neighborhoods with less environmental supports for healthy behaviors and higher rates of crime and poverty are at an increased risk for poor health (Ross & Mirowsky, 2001). Ross and Mirowsky have reported that residents living in disadvantaged conditions (i.e., low income and/or high crime) had higher rates of health problems. It is also well documented that the rate of overweight and obesity are on the increase. Ogden et al. (2006) have reported that results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reveal that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults (20 to 74 years) in the United States has increased from 56% in 1988-1994 to 66% in 2004-2005. In addition, obesity alone has increased from 23% to 32% for this group during the same time period. Also, minority and low-income populations are experiencing higher rates of overweight and obesity than the population in general (Flegal, Carrol, Ogden, & Johnson, 2002; Ogden et al., 2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2001; Yancey et al., 2004). Previous studies have consistently shown that individuals with low education levels, low income, and lower occupational status report being less physically active than less disadvantaged groups (Eyler et al., 2002; Iribarren, Leupker, McGovern, Arnett, & Blackburn, 1997; Seefeldt, Malina, & Clark, 2002; USD-HHS, 1996; Wilson, Kirtland, Ainsworth, & Addy, 2004).

Several studies have demonstrated an association between neighborhood environmental and social factors and physical activity (Brownson et al., 1996; Brownson et al., 2000; Brownson et al., 2001; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1999; Corti et al., 1996; Craig, Brownson, Cragg, & Dunn, 2002; Doucette, Saelens, Sallis, & Strelow, 2001; Eyler et al., 2002; Humpel, Owen, & Leslie, 2002; Russell, Dzewaltowski, & Ryan, 1999; Seefeldt et al., 2002). For example, Fisher, Li, Michale, and Cleveland (2004) found that among older adults, neighborhood social cohesion, along with other neighborhood factors such as income level, population density, and the number of facilities per neighborhood acre, were significantly associated with neighborhood physical activity. In addition, in a study with more than 1,000 adults, both African American and White, Boslaugh, Luke, Brownson, Naleid, and Kreuter (2004) demonstrated that neighborhood-level characteristics influence participants' perceptions of their neighborhood as suitable in terms of neighborhood pleasantness and resource availability for physical activity.

In numerous studies conducted with adult and older-adult ethnic minority populations, lack of access and safety concerns were perceived barriers to physical activity (Carter-Nolan, Adams-Campbell, & Williams, 1996; Clark, 1999; Henderson & Ainsworth, 2000; Lavizzo-Mourey et al., 2001; Sanderson, Littleton, & Pulley, 2002; Seefeldt et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2004). These studies revealed that barriers related to access included lack of facilities, inadequate sidewalks, distance to facilities, lack of transportation to places to be physically active, high cost, and poor weather. Safety-related barriers included concerns regarding stray dogs, crime, victimization, uneven sidewalks, and traffic.

The purpose of this research was to identify from neighborhood residents the multiple levels of influence affecting physical activity within a specific neighborhood, as outlined by the ecological model (Booth et al., 2001; McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1998). This included determining whether residents identified neighborhood environmental and social factors associated with physical activity similar to those found in previous studies and, most important, to learn from residents how these factors can be incorporated into an intervention or program for change in their neighborhood. The present study is a qualitative assessment of neighborhood residents' perceptions of the physical activity barriers in their neighborhood and their suggestions regarding how to address these barriers in developing a community-based program to increase physical activity. The focus groups reported in this article were undertaken as an assessment in an early phase of working with a neighborhood to develop an intervention to increase physical activity.

This study expands on past qualitative research with African American residents living in low-income, high-crime communities by identifying broader ecological factors associated with physical activity in these communities and possible programmatic solutions for these factors. It also expands our understanding of how safety and social factors influence physical activity and how best to develop interventions to increase physical activity in disadvantaged minority communities. Specifically, the qualitative assessment addressed participants' perceptions about self, family, and community needs as a way to address those needs for future community-based interventions for increasing physical activity.

The ecological model is used as the guiding framework in this study and has become a useful framework for designing multilevel programs to address social and neighborhood-level factors (Eyler et al., 2002; Fleury & Lee, 2006; Glanz et al., 1995; King et al., 1995; Sallis, Bauman, & Pratt, 1998; Sallis & Owen, 1997; Walcott-McQuigg, Zerwic, Dan, & Kelley, 2001). This model postulates that behavior is impacted by multiple levels of influence including individual, interpersonal (friends and family), institutional, community, environment, and policy (Booth et al., 2001; McLeroy et al., 1998). Thus, the present study was conducted using an ecological model as the guiding framework for a planning process to develop a neighborhood-level program to increase physical activity through addressing multiple levels (individual, family, and community) of influence.

METHOD

Three focus groups were conducted with residents of a specific community. It was a small community, and it was determined that after three focus groups, there would be a saturation point regarding their barriers and suggested solutions.

Discussion Guide Development (Focus Group Questions)

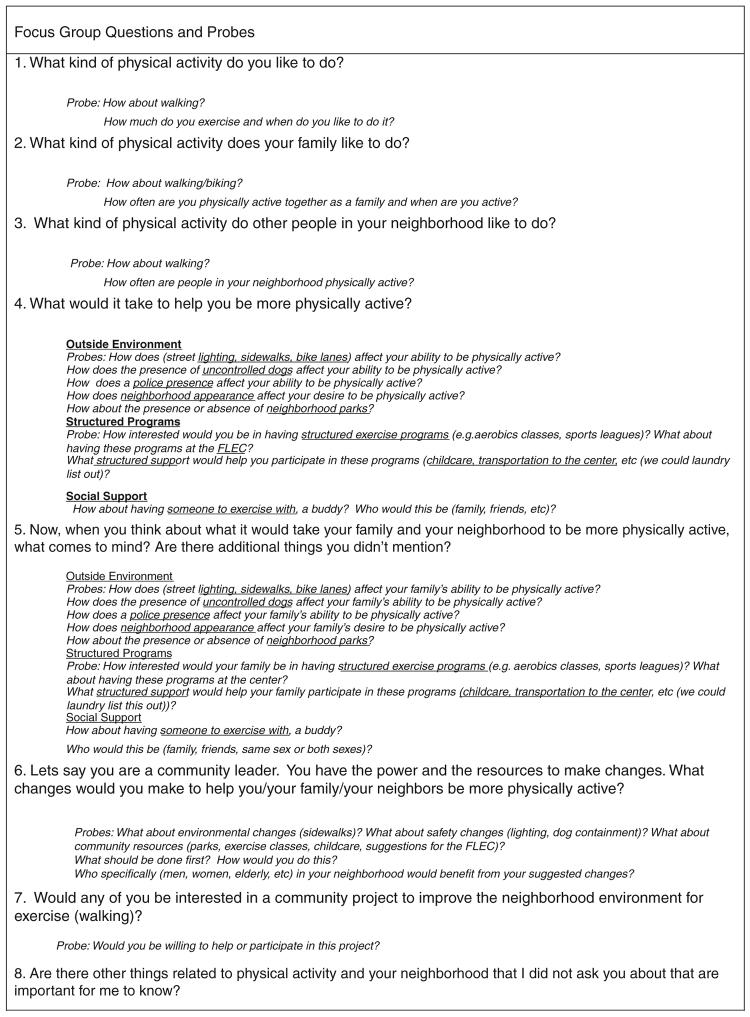

The ecological model was used in framing the questions for the discussion guide because of its use with planning the neighborhood-level program. Through previous conversations with neighborhood residents, it was felt that the factors influencing physical activity and solutions for increasing physical activity would be multilevel and would include interpersonal, social, and environmental variables. This research was undertaken as an assessment prior to designing an intervention; therefore, it was important to have a thorough understanding of the levels of influence on physical activity and the potential opportunities for intervention development. The discussion guide included questions aimed at increasing our understanding of participants' perceptions of interpersonal, social (family and neighbors), and environmental influences on their physical activity. In addition, the discussion guide included questions regarding suggested changes at the interpersonal, programmatic, social, and environmental level that would help them, their families, and their neighbors be more physically active (see Figure 1 for questions).

FIGURE 1.

Focus Group Questions

Prior to recruiting participants, the study protocol was approved by the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited to take part in one of three focus groups with the help of a local community center in a suburban southeastern community and provided informed consent prior to participation. A local liaison advertised the focus groups through several channels, including church bulletins, flyers around the community, and word-of-mouth in an effort to reach community leaders. Participants were paid $15 as an incentive for participating in the focus group. Although all participants were not community leaders, community leaders were specifically recruited for this study because of their knowledge about the neighborhood barriers as well as their knowledge and experience. It was also anticipated that these leaders would be involved in helping to implement the program developed as a result of this assessment.

Participants

All participants (n = 27) in this study were African American and all lived in or had strong ties to the community being assessed. More participants were female (70%) than male (30%). Only 1 participant was younger than 30, and most participants (66%) were 50 years old or older. The participants were fairly evenly distributed regarding education, with almost half (44%) having a college degree or higher and just fewer than half (44%) having a high school diploma. Slightly fewer than half (48%) reported having children living in their household. Thus, our sample tended to be older and slightly more educated than the general population in the county. See Table 1 for a more detailed presentation of participant demographics.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Table of Environment and PA Focus Group Participants

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8 | 29.6 |

| Female | 19 | 70.4 |

| Total | 27 | 100.0 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 27 | 100.0 |

| Age | ||

| 20 to 29 | 1 | 3.7 |

| 30 to 39 | 6 | 22.2 |

| 40 to 49 | 2 | 7.4 |

| 50 to 59 | 6 | 22.2 |

| 60 to 69 | 6 | 22.2 |

| 70 to 79 | 6 | 22.2 |

| Total | 27 | 100.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 12 | 44.4 |

| Single | 7 | 25.9 |

| Divorced | 8 | 29.6 |

| Total | 27 | 100.0 |

| Education level | ||

| Some high school | 3 | 11.1 |

| High school diploma | 12 | 44.4 |

| College diploma | 6 | 22.2 |

| Professional/graduate school | 6 | 22.2 |

| Total | 27 | 100.0 |

| Favorite physical activity | ||

| Walking | 19 | 70.4 |

| Tae-bo | 2 | 7.4 |

| Jogging | 1 | 3.7 |

| Basketball | 3 | 11.1 |

| Yard work | 1 | 3.7 |

| Working | 1 | 3.7 |

| Total | 27 | 100.0 |

| No. of children in household | ||

| 0 | 14 | 51.8 |

| 1 | 8 | 29.6 |

| 2 | 3 | 11.1 |

| 3 | 1 | 3.7 |

| 4 to 6 | 1 | 3.7 |

| Total | 27 | 100.0 |

NOTE: PA = physical activity.

Community

Census tract data for 2000 for this neighborhood show that the area consists of approximately 3,300 individuals: 98% of the residents are African American, 73% of adult residents have an annual income of less than $25,000, and the median household income is $16,804 as compared to a median household income of $37,082 for the state of South Carolina. More than half, 53%, of the residents have a high school degree or higher compared to a rate of 76% for the state. Forty-three percent of homes are owner occupied, and vacant housing is at 18%.

Crime data from the 2005 South Carolina Statistical Abstract (South Carolina Budget and Control Board, 2005) indicates that the community residents experienced higher rates of robbery, aggravated assault, and breaking and entering than the state rate. For example, the community rates represent 21 robberies, 87 aggravated assaults; 161 breaking and entering crimes per 10,000 residents compared to a state rate of 14 robberies, 61 aggravated assaults, and 103 breaking-and-entering incidences per 10,000 residents.

Focus-Group Facilitation Methods

All three focus groups were held at a local church-based community center in the early evening. Sessions were approximately 1.5 hours in length. Experienced moderators (both female) conducted the focus groups. Both moderators have been trained in qualitative data research and have extensive backgrounds in conducting focus group research. The moderators followed a standard protocol. The protocol included how to: introduce the focus group purpose, facilitate participant introductions, define desired group interaction, and ask the core questions and probes. Participants were informed that all information would be kept confidential and were encouraged to be open and honest in their responses. Last, each participant completed a short demographic survey containing items related to age, gender, ethnicity, and so forth. All sessions were audiotaped with the permission of the participants.

Focus group recordings were transcribed verbatim using a professional agency. The focus group moderator and a graduate assistant reviewed the transcripts for accuracy against the original recordings. Although the questions were framed using the ecological model, transcripts were reviewed using an open-coding process whereby no preconceived ideas about possible themes or codes were imposed on the coding structure. As themes, patterns of words, perceptions, ideas, and program suggestions were identified, they were classified into categories (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). From this list, a code book was developed. This code book was then used to code the transcripts. The two people who coded each transcript met to come to consensus on their codes after independently coding each transcript. Interrater reliability between the two coders (r = .70) indicated acceptable levels of agreement. Once the transcripts were coded, the codes were entered into QSR NVivo for content analysis structures as outlined by Miles and Huberman (1994). Through this process, themes emerged from the data using an inductive analysis. Themes were defined as topics, issues, or program suggestions that were discussed in more than one focus group.

RESULTS

The focus groups yielded information regarding environmental barriers to physical activity and proposed social and environmental solutions for overcoming barriers by focusing on community change through programs to enhance community connectedness/social support, increase structured programs, and increase law enforcement. Themes for improving neighborhood safety correspond to the interpersonal, community, environment, and policy aspects of the ecological model. All suggested solutions had an underlying emphasis on safety and crime prevention.

Environment

Environmental themes regarding barriers to physical activity clustered into two areas: safety-related and non-safety-related. Safety-related themes included comments regarding criminal and noncriminal factors; see Table 2 for a complete listing of the themes associated with each environmental category. More than two thirds of environmental comments with regard to barriers were related to safety issues (e.g., theft, prostitution, homicide, traffic, etc.) rather than non-safety-related issues (e.g., lack of sidewalks, lack of walking paths, poor neighborhood environmental infrastructure, etc.). Below is a summary of themes in both categories and quotes by participants that illustrate each theme.

TABLE 2.

Environmental Themes and Suggestions for Community Change to Increase Physical Activity

| Category | Themes |

|---|---|

| Environmental Categories and Themes | |

| Safety-related | Criminal activity

|

Noncriminal activity

|

|

| Non-safety-related | Access to environmental supports

|

| Community Change Themes | |

| Community connectedness and social support | Community building Increasing individual support |

| Structured programs Law enforcement activities |

|

Safety-Related Themes—“Fear Is Here”

This category of themes is summed up in one participant's comment: “Fear is here.” This reflects the mood of the safety-related themes emerging from these focus groups. As stated above, an overwhelming majority of the environment-related comments concerned safety. Another participant summed up this category with the following: “But, again, it's the thing of security, the protection, the sense of security—that's the important thing.”

There were several themes within the safety category representing criminal activity and comments and representing noncriminal activity. Non-criminal-related comments were those that explicitly spoke to safety and fear but did not clearly speak to crime. These included comments regarding stray dogs, lighting, and traffic. Most of the comments related to stray dogs and fear of walking came from women. Women frequently made comments similar to the following by one participant: “I can't walk in the neighborhood because of the stray dogs.”

Participants also commented on the lack of lighting in the neighborhood and the feeling of insecurity it brought them. Participants often talked of wanting to walk at night, but they were fearful of being out alone because of the lack of lighting. They also discussed being afraid of going out late in the day or at night to centers to participate in programs because of the lack of lighting and fear of being in such poorly lit areas. The following quotes from two different participants in different focus groups illustrate this theme: “It is not safe to walk. You know, it's not that you don't want to—you can't. You know, it [sic] not safe to be out after the sun goes down, you know, definitely not in the wintertime. In the summer, you have a little more light” and “I want to walk at night, but I can't because there are no street-lights and the stray dogs.”

Criminal-related concerns often addressed specific examples of past crimes or fear of specific types of crimes. These comments included specific references to drug trafficking, muggings, theft, prostitution, homicide, and desire for more action by police to curtail these activities in their neighborhood. Participants in all three focus groups talked about the presence of drug dealing in their neighborhood and how that affects their not wanting to get out in their neighborhood. The following quotes illustrate this problem: “But it's really and truly not safe to walk. … We're in a neighborhood where drug dealing goes on the side of me and in front of me” and “ … convoy of 18 wheeler, you could see them … I couldn't figure out what it was, and I got up and you can see them coming down the street, stop, and they buy their drugs.”

Participants, mostly women, expressed fear of muggings and theft. Some participants expressed personal concerns about being robbed and others expressed concerns regarding theft. One participant stated, “When you are walking, you don't really have your purse, but they still can mug you.” Another said, “Sometimes I have heard people talk about the fact that they've gone out to places and their cars with the nice wheels on them when they were in, and they came back out, their cars were on blocks.”

Finally, participants in all three focus groups brought up a recent shooting of a 13-year-old child in an area park and described how after it occurred, many children were not allowed outside because of the shooting. Participants said the following about the incident: “I guess the main thing that comes to mind is the death of that girl they found over in [name] park. You know, you don't really know the circumstances of that, but still … it's an eerie feeling about traveling alone on foot” and “Many people don't let their kids out the house because of it (the shooting)—they scared.”

All of the above comments provide a clear sense of the level of fear that affects the daily lives of people living in this neighborhood and how it inhibits their ability to get outside of their homes to be more physically active.

Non-Safety-Related Themes

Non-safety-related themes primarily addressed issues of access to environmental supports for physical activity, including having trails, infrastructure, facilities, and aesthetics. For example, participants were concerned about the lack of adequate sidewalks when asked, “What would it take to help you be more physically active?” One participant stated, “Sidewalks, we don't have them.”

Often sidewalks are directly linked to safety concerns (Henderson & Ainsworth, 2000; Seefeldt et al., 2002); however, these participants did not make that connection in their discussion. They only talked about sidewalks in terms of not having them, similar to how they discussed the lack of trails in their community.

Non-safety-related comments related to the lack of trails in their neighborhood and having to get in a car to drive to a park or trail to walk. For example, 1 participant illustrated this theme by saying, “If I want to walk, I have to get in my car and drive over to [name] park and walk. There are no trails in my neighborhood.”

Participants spoke of a lack of infrastructure and facilities in their neighborhood. Infrastructure comments were related to inadequate zoning and maintenance, leading to problems related to water runoff or standing water in their neighborhood and lack of basic maintenance. For example, 1 participant described maintenance of roads as “the roads have become a problem. They don't even pave, they don't resurface the roads, they just patch the roads.”

In discussing resources in their neighborhood, participants frequently mentioned the neighborhood gym that was no longer open. One participant described its decline and closure as follows: “They had a pool and everything … but then they closed … so when you take that into consideration there isn't a lot a family can do in [neighborhood name].”

Aesthetics comments related to people not wanting to get outside and walk because of neighborhood appearance. One participant said that it “just looks run-down, like nobody lives here.”

Proposed Solutions for Community Change to Increase Physical Activity

Participants had suggestions for ways to change their community. They thought that these changes would also increase their own, their family's, and their neighbors' level of physical activity. Participants identified three areas to target for change in an effort to increase physical activity. Comments were clustered into three primary themes: law enforcement, community connectedness and social support, and structured programs. The majority of comments related to improving safety in the neighborhood involve efforts to increase social support and community connectedness (see Table 2 for a complete listing of themes related to suggestions for changes). Participants clearly stated that they wanted to be a part of the solution and that the solution involved more than simply bringing in programs and resources to fix their neighborhood from the outside.

Community Connectedness/Social Support

Community connectedness and/or social support included comments about wanting to increase the sense of connectedness with neighbors and how social support would help to increase physical activity. Participants discussed bringing people from the neighborhood together; however, the purposes were different. For example, comments regarding community connectedness related to how to make the neighborhood safer or how to get people out of their houses and being more physically active in the neighborhood. This theme included comments such as:

Maybe through a block party … and maybe they will come out and just talk to them or find something. If we could just get together more.

Yeah, coming together and see the neighborhood and everybody out watching out for each other.

People in our neighborhood are afraid to come out. It takes a community to combat a problem.

Block parties. [Parties] where you just shut down the whole block and you, with your neighbors and everybody, cook and have music and you dance until midnight and you didn't have to worry about hearing a gun go off, worry about people arguing, worry about drugs being sold. You had fun, and you didn't have to worry about where your children were because everybody in that block, everything was shut off. No one could get in and everyone's doors were open, and for that one minute, you could fellowship and just not worry about anything else, not worry about your house.

Some older participants also suggested an intergenerational approach, as illustrated by the following quote:

You might be old and decrepit as far as they're concerned. We're thinking they're young and off the cuff, you know, but once we can pull the two together and to make exercise something that is fun, it's a fellowship, it's an opportunity for us to get to know each other.

In addition, many participants thought that this community building should come from within by the local leadership and the local faith organizations taking the lead in organizing events for the neighborhood.

I would get the churches more involved. Most of the churches have a health ministry, and usually, from my observation, the health ministry is a good ministry, … they have their boosts and whatnot, but if I had the power and the ability to invoke change, I would do it through congregation by example.

Participants also made comments regarding neighbors supporting and helping each other. Most of these comments came from female participants and were regarding having someone to be physically active with them, such as the following: “I don't like to walk alone either, just walking alone, and so when we do it we do it together, and yard work too, we do that together.”

Structured Programs

In discussing structured programs, participants spoke about their desire to have these programs physically located in the neighborhood. Most of these comments related to programs for youth or for families. As with the community connectedness theme, several older residents suggested intergenerational programs. The comments below illustrate this theme.

Maybe we could get more involved by getting together with our younger people, getting them involved in basketball or what, you know, sports of that sort. If we could get a safe baseball field for them to play with, we won't have to worry about the grownups come and taking over that and just let it be for the younger people and not having no drinking and whatever behind them.

If I were to come then and I have somebody with special needs and they could come, something that could be used to occupy their time physically, physical activities or something.

Law Enforcement

Participants made several comments about wanting a more visible police presence in the neighborhood. Comments related to the desire for more police action covered several different areas from traffic to drugs to prostitution. The following quotes provide two examples: “It would be good to have more police protection” and “so the enforcement of the laws have just been benign and almost nonexistent when it comes to us in certain parts of town.”

To further illustrate how much participants desired a more safe neighborhood, the following comments are specific suggestions related to the desire for more law enforcement in the neighborhood and what participants would like law enforcement to do to help improve their neighborhood. These comments demonstrate how fear was a clear contributor to participants getting “out and about” in their neighborhood. When asked what should be done first, one participant stated it in one simple phrase: “Safety … we need to feel safe.” Participants in all three focus groups made comments such as “Get the drug dealer out” and “I would like to have a place to walk, but I need to know it is going to be safe and when it is going to be safe when the police will be there” (in reference to having a walking path).

DISCUSSION

This study's qualitative findings show that the perceived environmental barriers to physical activity experienced in this community were similar to findings in previously cited studies identifying environmental factors influencing physical activity among minority populations (Eyler et al., 2002; Fisher et al., 2004; Seefeldt et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2004). Participants of this study identified several safety- and non-safety-related areas of influence. This study extends the current research by identifying specific community-generated methods for addressing safety as a means to increase physical activity.

Although safety-related issues were not the only issues discussed by the participants, most of their suggestions had a safety-oriented component. In addition, the residents made suggestions that focused on increasing residents' sense of community and community connectedness as a way to increase perceived safety and help people feel more comfortable being out in their neighborhood. This is consistent with Fisher et al.'s (2004) findings that social cohesion is an important factor influencing physical activity. Also, the emphasis on social connections within the community is compatible with the Task Force on Community Preventive Services (2002) recommendation for increasing social support as a component of community-based interventions. Although addressing these safety-related concerns alone are not enough, the participants pointed out that by addressing these first and then building neighborhood connectivity, the program would have a greater level of success with implementing other non-safety-related components of the program in the neighborhood to increase physical activity.

This study showed that community residents had clear, multilevel ideas about how to improve on safety concerns and increase physical activity in their neighborhood. For example, they offered suggestions at the interpersonal level (i.e., walking buddies, structured intergenerational programs), community level (i.e., community watch programs, social events), and environmental level (i.e., get the drug dealers out, have a stronger police presence). Without the information from this assessment, the program developers would not have gained a clear understanding of just how crucial addressing safety was to the success of any physical activity program in the neighborhood. In addition, the program developers would not have known how the community wanted to address their safety concerns, particularly their interest and desire for more social interaction and community connectedness as a way to combat crime in their area.

The specific examples of how to address crime and increase physical activity suggest that residents want to address issues through multiple components, including social support and community-related efforts. Although they requested some help from law enforcement, they also want their interventions to have social support components and community connectedness components in an effort to address some of the environmental barriers. Participants from this community wanted the solutions to be “internal” and involve the community by increasing confidence and recognition of the communities' capacity to work on their own issues with some help. They want law enforcement to work with them in solving their problems and for community members to demonstrate social support for change in their community by taking steps to first get to know each other and support each other as neighbors. Some of these specific suggestions made by participants were novel and worthy of further exploration. This is in keeping with community mobilization and community-driven health promotion program development as outlined by Israle, Schulz, Parker, and Becker (1998) and Minkler and Wallerstein (2003).

Several limitations to the present study should be noted. First, the sample size was small and not representative of the entire neighborhood. In addition, slightly more than half of the participants were older than the age of 50, but just fewer than half of them still had children living in their home. Participants' age may have influenced their responses. Several of the studies cited earlier with older adults (Clark, 1999; Henderson & Ainsworth, 2000; Lavizzo-Mourey et al., 2001) found similar findings related to safety and fear. Despite these limitations, this study does still provide some insight into what people in this neighborhood experience in their daily lives and how that affects their physical activity level. Last, it is important to be mindful that the focus groups were conducted fairly soon after a particularly disturbing shooting of a 13-year-old child. This shooting was mentioned several times in each of the three focus groups and may have had some impact on the participants' overwhelming emphases on safety and crime as the primary issue in their neighborhood.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study provides findings that replicate other findings suggesting that safety-related issues are important barriers to physical activity for individuals living in low-income, high-crime neighborhoods. These safety-related factors include both criminal and noncriminal activities and seem to instill a sense of fear in these disadvantaged communities. This study illustrates how improving safety may directly help in efforts to increase physical activity; safety may serve as a mediator for success. In addition, this study shows that residents have ideas about how to address safety-related issues in a way that builds community connectedness and social cohesion and that encourages residents to want to be part of these efforts. Finally, the findings illustrate the importance of doing a community assessment involving local residents when planning an intervention for change. This assessment provided a wealth of descriptive information that helped guide the development of an intervention program for underserved communities.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the Cardiovascular Health Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cooperative agreement U48/CCU409664-06 (Prevention Research Centers Program).

Contributor Information

Sarah F. Griffin, An assistant professor with the Department of Public Health Sciences, College of Heath, Education, and Human Development, Clemson University in Clemson, South Carolina..

Dawn K. Wilson, A professor in the Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina in Columbia, South Carolina...

Sara Wilcox, An associate professor in the Department of Exercise Science with the Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina in Columbia, South Carolina..

Jacqueline Buck, The evaluation coordinator for a ENRICH project with the Department of Health Promotion, Education and Behavior with the Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina in Columbia, South Carolina...

Barbara E. Ainsworth, A professor in the Department of Exercise and Wellness at Arizona State University in Mesa, Arizona..

REFERENCES

- Booth SL, Sallis JF, Ritenbaugh C, Hill JO, Birch LL, Frank LD, et al. Environmental and societal factors affect food choice and physical activity: Rationale, influences, and leverage points. Nutrition Review. 2001;59(3 Pt 2):S21–S39. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb06983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boslaugh SE, Luke DA, Brownson RC, Naleid KS, Kreuter MW. Perceptions of neighborhood environment for physical activity: Is it “who you are” or “where you live”? Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2004;81:671–681. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Smith CA, Pratt M, Mack NE, Jackson-Thompson J, Dean CG, et al. Preventing cardiovascular disease through community-based risk reduction: The Bootheel Heart Health Project. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;88(2):206–213. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Houseman RA, Brown DR, Jackson-Thompson J, King AC, Malone BR, et al. Promoting physical activity in rural communities: Walking trail access, use, and effects. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18:235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Baker EA, Houseman RA, Brenna LK, Bacak SJ. Environmental and policy determinants of physical activity in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1995–2003. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Nolan PL, Adams-Campbell LL, Williams J. Recruitment strategies for Black women at risk for non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus into exercise protocols: A qualitative assessment. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1996;88:558–562. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Neighborhood safety and the prevalence of physical activity, 1996: Selected states. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 1999;46:143–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DO. Identifying psychological, physiological, and environmental barriers and facilitators to exercise among older low income adults. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 1999;5:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Craig CL, Brownson RC, Cragg SE, Dunn AL. Exploring the effect of the environment on physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23(Suppl):36–43. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucette A, Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Strelow J. Association of walking with neighborhood characteristics (Abstract) Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;23:S097. [Google Scholar]

- Eyler AA, Wilcox S, Matson-Koffman D, Evenson KR, Sanderson B, Thompson J, et al. Correlates of physical activity among women from diverse racial/ethnic groups. Journal of Women's Health and Gender-Based Medicine. 2002;11(3):239–253. doi: 10.1089/152460902753668448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carrol MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2000. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) 2002;288:1723–1730. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher KJ, Li F, Michale Y, Cleveland M. Neighborhood-level influences on physical activity among older adults: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2004;11:45–63. doi: 10.1123/japa.12.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleury J, Lee SM. The social ecological model and physical activity in African American women. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;37(1):129–140. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-9002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Lankenau B, Foerster S, Temple S, Mullis R, Chmid T. Environmental and policy approaches to cardiovascular disease prevention through nutrition: Opportunities for state and local action. Health Education Quarterly. 1995;22:512–527. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson KA, Ainsworth BE. “It takes a village” to promote physical activity: A case study of the potential for physical activity (Abstract) Research Quarterly of Exercise and Sport. 2000;71:15. [Google Scholar]

- Humpel N, Owen N, Leslie E. Environmental factors associated with adults' participation in physical activity: A review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22(3):188–199. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren C, Leupker RV, McGovern PG, Arnett DK, Blackburn H. Twelve-year trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors in the Minnesota Heart Survey: Are socioeconomic differences widening? Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157(8):873–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israle BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Jeffery RW, Fidinger F, Dusenbury L, Provence S, Hedlund SA, et al. Environmental and policy approaches to cardiovascular disease prevention through physical activity: Issues and opportunities. Health Education Quarterly. 1995;22:499–511. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavizzo-Mourey R, Cox C, Strumpf N, Edwards WF, Stinemon M, Grisso JA. Attitudes and beliefs about exercise among elderly African Americans in an urban community. Journal of National Medical Association. 2001;93(12):475–480. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KB, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health. 1st ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. The Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42(3):258–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell WD, Dzewaltowski DA, Ryan GJ. The effectiveness of a point-of-decision prompt in deterring sedentary behavior. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1999;13:257–259. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-13.5.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Bauman A, Pratt M. Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;15:379–397. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Owen N. Ecological models. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer B, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 2nd ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1997. pp. 403–424. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson B, Littleton M, Pulley L. Environmental, policy, and cultural factors related to physical activity among rural, African American women. Women's Health. 2002;36(2):75–90. doi: 10.1300/j013v36n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seefeldt VJ, Malina RM, Clark MA. Factors affecting levels of physical activity in adults. Sports Medicine. 2002;32(3):143–168. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South Carolina Budget and Control Board. Office of Research and Statistics South Carolina statistical abstract. 2005 Retrieved May 26, 2006, from http://www.ors2.state.sc.us/abstract/index.asp.

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services Recommendations to increase physical activity in communities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22(4S):67–72. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; Atlanta, GA: Physical activity and health: A report of the Surgeon General. 1996

- USDHHS. Public Health Services. Office of the Surgeon General . The Surgeon General's call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. Author; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcott-McQuigg JA, Zerwic JJ, Dan A, Kelley MA. An ecological approach to physical activity in African American women. Women's Health. 2001;6(6):3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DK, Kirtland K, Ainsworth B, Addy CL. Socioeconomic status and perceptions of access and safety for physical activity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28:20–28. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Kumanyika SK, Ponce NA, McCarthy WJ, Fielding JE, Leslie JP, et al. Population-based interventions engaging communities of color in healthy eating and active living: A review (Serial online) Preventing Chronic Disease. 2004 Retrieved August 17, 2005, from http://www.cdc.gov./pcd/issues/2004/jan/03_0012.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed]