Abstract

Purpose

The goal of this study was to compare results of open arthrotomy versus arthroscopic drainage in treating septic arthritis of the hip in children.

Methods

This prospective controlled study was conducted on twenty patients (20 hips) with acute septic arthritis of the hip. Diagnosis was suspected if there was: a history of fever, non-weight-bearing on the affected limb, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of at least 40 mm/h, and white blood cell count of more than 12,000 cells per cubic millimeter. Diagnosis was established by ultrasonographic examination of the affected hip followed by ultrasound-guided aspiration of the joint. Patients were allocated to have either open arthrotomy or arthroscopic drainage of the joint. There were ten patients (ten hips) in each treatment group. The mean age of the patients was 7.3 years in the arthrotomy group, and 8 years in the arthroscopy group. The mean temperatures for the arthrotomy and arthroscopy groups were 38.8 and 38.7°C, respectively. All the children were unable to bear weight on the affected limb.

Results

Staphylococcus aureus was the most common causative microorganism in both groups. The mean duration of the children’s hospital stay was 6.4 days in the arthrotomy group and 3.8 days in the arthroscopy group. The difference was highly significant. Infection could be eradicated in all patients of both groups. At the latest follow-up, seven children in the arthrotomy group (70%) had excellent results and three children (30%) had good results. In the arthroscopy group, nine children (90%) had excellent results and one child (10%) had good results. The difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusions

Arthroscopic drainage is an effective method in treating septic arthritis of the hip. It is a minimal invasive procedure which is associated with less hospital stay. Arthroscopic drainage of septic arthritis of the hip in children is a valid alternative procedure in early uncomplicated cases and for orthopedic surgeons skilled in pediatric arthroscopy.

Keywords: Septic arthritis, Hip joint, Arthroscopy, Children

Introduction

Acute septic arthritis of the hip in children is an orthopedic emergency that necessitates early diagnosis and effective treatment to ensure preservation of a normal structure and full function of the joint, and to minimize the occurrence of severely disabling life-long disastrous sequelae [1–3]. Delayed diagnosis and ineffective treatment are associated with such complications as avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head, osteomyelitis, chondrolysis, systemic sepsis, leg length discrepancy, and later osteoarthritis of the hip joint [1–3]. Open arthrotomy drainage and thorough irrigation of the joint is considered the standard treatment for septic arthritis of the hip [2, 3]. Hip arthroscopy, used as a diagnostic or therapeutic tool in certain indications, has some advantages over arthrotomy. It is less invasive and allows for quicker recovery and return to activities [4]. Arthroscopic lavage is considered the treatment of choice for patients with septic arthritis of the knee [5], it has also been advocated in the treatment of patients with septic arthritis of the hip [4, 6–11]. However, arthroscopic treatment of this condition is still not an established technique, despite its minimally invasive nature. This is especially true for children with septic arthritis of the hip joint [4].

The goal of the current study was to compare results of open arthrotomy versus arthroscopic drainage in the treatment of septic arthritis of the hip joint in children.

Materials and methods

This prospective controlled study was carried out during the period between July 1998 and December 2005 at Hai Al-Jamea hospital, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. During that period, 23 children with acute septic arthritis of the hip were treated in the hospital and were eligible to be included in the study after obtaining a formal consent from the child’s family to include their child in the ongoing study.

The following criteria were used for patient inclusion in the study:

normal child between 3 and 12 years old;

established diagnosis of acute septic arthritis of the hip joint;

early presentation of no more than five days since onset of symptoms;

minimum follow-up period of 12 months after the surgical procedure; and

complete set of medical records, pre and post-operative radiographs, and videotape record for the arthroscopic procedure.

The exclusion criteria used in this study were:

patients with tuberculous or fungal infection of the hip joint;

coexistence of osteomyelitis of the proximal femur, pelvis, or acetabulum;

late presentation of more than five days after the onset of symptoms;

immunocompromised children;

children with physical or mental disabilities; or

children with pre-existing pathology, deformity or surgery of the affected hip.

The lower age limit for the children to be included in the study was set to be three years to exclude any effect of patient’s age on the final outcome [12–20]. Most authors agree that neonates and infants are more likely to have unsatisfactory results than children older than three years of age [12, 14–19]. Other authors did not show any significant difference in the outcome between younger and older age groups especially if the disease was treated early [13, 20].

The maximum duration of delayed presentation after the onset of symptoms in this study was set at five days in order to avoid the deleterious effect of delayed treatment on the final outcome when comparing the results of treatment of the condition by either arthrotomy or arthroscopy. There is a consensus of opinion that, regardless of treatment method, the single most important factor determining the outcome of septic arthritis is early treatment, with poor results most often due to late diagnosis and delayed treatment [1–3, 12, 18–22]. However, the duration of the delay is not clearly defined in most studies. Bennett and Namnyak [12] and Morrey et al. [20] reported satisfactory results in patients treated within four days of onset whereas Paterson [22] and Chen et al. [13] set the limit at five days. Moreover, at the author’s institution, cases with septic hips diagnosed later than five days after onset of symptoms are drained via an anterior approach arthrotomy to allow easy access to the proximal femoral metaphysis for inspection and possible drilling.

Among the 23 children treated in the hospital, 20 patients (20 hips) with a follow-up period of more than 12 months were included in this study. The remaining three children were excluded from the study as they did not attend the final follow-up visit. There were eleven boys (55%) and nine girls (45%), with a mean age of 7.7 years (range 3–12). The right hip was affected in eleven patients (55%) and the left hip in nine patients (45%).

After thorough clinical evaluation, radiographic examination of the hip joint and laboratory tests including complete and differential blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) were performed in all patients.

Kocher’s criteria [23] for calculating the predicted probability of septic arthritis were used for early clinical diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip. Ultrasonographic examination of the affected hip joint was carried out for patients with a suspected septic hip followed by ultrasound guided aspiration of the hip joint under conscious sedation [24, 25]. The aspirate studies included synovial fluid total and differential leukocyte count and culture and sensitivity.

Diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip was established when one or more of the following findings were found in patients with a suspected septic hip:

pus or turbid fluid aspirate from the hip joint;

total synovial white blood cell (WBC) count exceeding 50,000 cells per cubic millimeter, of which more than 90% are polymorphonucleocytes [2, 21].

The presence of a positive bacterial culture from specimens of synovial fluid aspirate or joint fluid taken during surgery was considered as a confirmatory evidence for the diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip.

Surgical procedure

After diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip was established, the patients were randomized to have either open arthrotomy of the hip joint or arthroscopic drainage and lavage. The families of all the children included in the study agreed to the participation of their children in the study and the management plan for their children. The surgical procedure was performed as an emergency procedure immediately after ultrasonographically guided needle aspiration of the joint and the results from synovial fluid analysis were available, without waiting for results from culture and sensitivity tests.

Hip joint arthrotomy was performed via an anterior approach. The joint capsule was incised and the joint was drained, thoroughly debrided, and irrigated with copious amounts of normal saline solution. The wound was closed over a suction drain placed within the joint capsule inferior to the femoral neck.

Hip arthroscopy was performed with the patients placed in a supine position on a fracture table. Gentle and sufficient traction was applied to distract the joint 5 mm in young children and 10 mm in older ones as observed on the image intensifier. Three arthroscopic portals of the hip were used—anterolateral, posterolateral, and anterior “if needed” [10, 26–29]. The 4-mm 30° scope was used and switched between portals. Arthroscopic drainage of the joint was carried out followed by irrigation with copious amounts of normal saline solution. Negative suction was used during the procedure to help thorough evacuation of debris, viscous fluid, and fibrin clots. A suction drain tube was inserted through the arthroscopic sheath. The portals were closed over suction drain.

Simple bed rest with a short period of skin traction was used postoperatively for pain relief during the hospital stay. Early range of motion of the hip joint was initiated as soon as the pain became tolerable, to prevent tissue adhesions and joint stiffness. The suction drain was removed when there was less than 20 ml clear fluid/24 h with no fever over the last 12 h. Initially, intravenous ceftriaxone was used empirically until the results of culture indicated sensitivity of the causative organism, thereafter, the antibiotics were changed accordingly. Children were discharged home after adjustment of the antimicrobial therapy according to the culture and sensitivity test, with the absence of fever for at least 24 h after removal of the drain and with tolerable pain that can be managed by the parents at home. Parenteral antimicrobial therapy was used for a total period of 10 days, followed by oral antibiotics for an additional 4 weeks. The duration of antimicrobial therapy was based on the clinical response, the infecting microorganism, and ESR and CRP levels. The patients were instructed to avoid weight bearing on the affected limb for two weeks after the procedure to be followed by partial weight bearing using two crutches for another two weeks. Young patients who could not walk by partial weight bearing were instructed to avoid weight bearing for three weeks until they are able to walk without any support.

Follow-up and method of evaluation

The patients were followed-up regularly after discharge at the outpatient clinic at two-week intervals for the initial six weeks and at variable periods thereafter, depending on the progress of the patient.

The final results were graded as excellent, good, fair, and poor according to Bennett’s classification which included clinical and anatomical (radiographic) evaluation scales [12].

Initial patient evaluation

There were ten patients (ten hips) in each treatment group. The mean age of the patients in the arthrotomy group at the time of surgery was 7.3 years (range 3–11), and it was eight years (range 4–12) in the arthroscopy group. There were six boys in the arthrotomy group (60%) and five boys in the arthroscopy group (50%). The right hip joint was affected in five children (50%) in the arthrotomy group and it was affected in six children (60%) in the arthroscopy group (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1.

Patients data

| Patient no. | Group | Age (years) | Sex | Side | Temperature (°C) | Delayed presentation (days) | Serum WBC × 109 cells/L | ESR (mm/hr) | CRP (mg/L) | Aspirate WBC × 109 cells/L | Aspirate Neutrophils (%) | Follow up (months) | Post-op. drain (days) | Hospital stay (days) | Microorg. | Duration of antibiotic (days) | Pain | Range of motion of hip | Final score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | 3 | B | Rt. | 38.5 | 1 | 8.2 | 23 | 29 | 33.0 | 88 | 14 | 2 | 6 | Strept. Pn. | 35 | No P | Full | E |

| 2 | S | 8 | B | Rt. | 39.3 | 2 | 9.3 | 38 | 32 | 25.0 | 82 | 29 | 2 | 3 | Staph. A. | 37 | No P | Full | E |

| 3 | A | 6 | B | Lf. | 39.1 | 3 | 11.6 | 35 | 46 | 49.0 | 79 | 21 | 3 | 5 | Staph. A. | 39 | Jn A | Full | G |

| 4 | S | 4 | G | Lf. | 38.6 | 4 | 11.0 | 28 | 48 | 59.0 | 89 | 24 | 3 | 4 | Staph. A. | 43 | No P | Full | E |

| 5 | A | 11 | B | Rt. | 38.9 | 3 | 17.8 | 73 | 39 | 27.0 | 84 | 23 | 3 | 7 | E. Coli | 44 | No P | Full | E |

| 6 | S | 10 | B | Rt. | 38.7 | 3 | 15.3 | 99 | 33 | 43.0 | 79 | 18 | 2 | 3 | Strept. Pn. | 49 | No P | Full | E |

| 7 | A | 7 | G | Lf. | 38.3 | 2 | 15.3 | 27 | 53 | 55.0 | 90 | 29 | 2 | 5 | Strept. Pn. | 52 | No P | Full | E |

| 8 | S | 8 | G | Rt. | 38.4 | 5 | 17.2 | 49 | 75 | 56.0 | 83 | 14 | 2 | 3 | Staph. A. | 47 | Jn A | Full | G |

| 9 | A | 5 | G | Rt. | 39.6 | 5 | 21.7 | 45 | 49 | 48.0 | 89 | 19 | 5 | 7 | Staph. A. | 42 | Jn A | L. Abd. | G |

| 10 | S | 9 | G | Lf. | 39.1 | 3 | 23.5 | 59 | 53 | 62.0 | 88 | 25 | 1 | 4 | Strept. Py. | 53 | No P | Full | E |

| 11 | A | 10 | B | Rt. | 38.6 | 1 | 12.4 | 67 | 73 | 33.0 | 82 | 25 | 2 | 4 | No G | 38 | No P | Full | E |

| 12 | S | 6 | B | Rt. | 38.0 | 1 | 8.9 | 77 | 61 | 35.0 | 81 | 30 | 3 | 5 | Staph. A. | 38 | No P | Full | E |

| 13 | A | 6 | G | Lf. | 39.4 | 2 | 6.7 | 88 | 57 | 51.0 | 77 | 39 | 4 | 9 | Staph. A. | 47 | No P | Full | E |

| 14 | S | 11 | G | Lf. | 37.9 | 3 | 13.2 | 86 | 75 | 23.0 | 85 | 26 | 3 | 3 | Staph. A. | 44 | No P | Full | E |

| 15 | A | 8 | B | Rt. | 37.8 | 4 | 19.1 | 90 | 66 | 41.0 | 86 | 17 | 3 | 8 | Staph. A. | 46 | No P | Full | E |

| 16 | S | 7 | B | Lf. | 39.4 | 5 | 16.6 | 42 | 41 | 55.0 | 87 | 21 | 2 | 3 | Strept. Pn. | 48 | No P | Full | E |

| 17 | A | 9 | G | Lf. | 39.2 | 4 | 15.8 | 49 | 78 | 28.0 | 69 | 27 | 4 | 7 | Staph. A. | 40 | No P | L Ex Rt | G |

| 18 | S | 5 | G | Rt. | 38.0 | 4 | 18.7 | 86 | 67 | 45.0 | 80 | 17 | 1 | 6 | Strept. Pn. | 51 | No P | Full | E |

| 19 | A | 8 | B | Lf. | 38.7 | 1 | 13.2 | 54 | 82 | 53.0 | 82 | 16 | 2 | 6 | K. Pneum. | 50 | No P | Full | E |

| 20 | S | 12 | B | Rt. | 39.5 | 2 | 19.4 | 44 | 23 | 38.0 | 87 | 13 | 4 | 4 | Staph. A. | 46 | No P | Full | E |

A arthrotomy group,S arthroscopy group,B boys,G girls,Rt right side,Lf left side,Staph. A.Staphylococcus aureus,Strept. Pn.Streptococcus pneumonia,Strept. Py.Streptococcus pyogenes,E. ColiEscherichia coli,K. Pneum.Klebsiella pneumoniae,Jn A joint aches,L. Abd. limited abduction,L Ex Rt. limited external rotation,E excellent,G good

Table 2.

Characteristics of the arthrotomy and arthroscopy groups of patients

| Arthrotomy group | Arthroscopy group | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients (hips) | 10 | 10 |

| Average age (years)a | 7.3 (3–11) | 8 (4–12) |

| Boys | 6 (60%) | 5 (50%) |

| Girls | 4 (40%) | 5 (50%) |

| Right side | 5 (50%) | 6 (60%) |

| Left side | 5 (50%) | 4 (40%) |

| Temperature (°C)a | 38.8 (37.8–39.6) | 38.7 (37.9–39.5) |

| Duration of delay (days)a | 2.6 (1–5) | 3.2 (1–5) |

| WBCs × 109 cells/La | 14.2 (6.7–21.7) | 15.3 (8.9–23.5) |

| Neutrophils × 109 cells/La | 10.7 (5.0–15.8) | 10.9 (5.7–17) |

| ESR (mm/h)a | 55.1 (23–90) | 60.8 (28–99) |

| CRP (mg/L)a | 57.2 (29–82) | 50.8 (23–75) |

| Synovial aspirate WBCs × 109 cells/La | 41.8 (27–55) | 44.1 (23–62) |

| Synovial aspirate Neutrophils (% of aspirate WBCs count)a | 82.6 (69–90) | 84.1 (79–89) |

| Average follow-up (months)a | 23 (14–39) | 21.7 (13–30) |

aValues are mean (range)

In three children (30%) among the arthrotomy group and five children (50 %) among the arthroscopy group there was a history of trauma incident prior to the appearance of presenting symptoms. In two children (20%) among the arthrotomy group and four children (40%) among the arthroscopy group there were a history of tonsillitis or upper respiratory tract infection that preceded the appearance of presenting symptoms. This infection was treated by antibiotics in these cases.

The mean temperatures for the arthrotomy and arthroscopy groups were 38.8°C (range 37.8–39.6°C), and 38.7°C (range 37.9–39.5°C), respectively. All the children included in this study presented with pain around the affected hip joint and inability to bear weight on the affected limb. There was tenderness at the anterior aspect of the affected hip in all cases. The range of both passive and active movements was limited in all children.

The mean period of delay after appearance of symptoms was 2.6 days (range 1–5) for the arthrotomy group and 3.2 days (range 1–5) for the arthroscopy group. The results of the blood tests for both groups are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Radiographic examination of the affected hips did not reveal any changes apart from fullness of the joint capsule of the affected hips in most cases.

According to Kocher’s clinical predictors for diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip joint [23], one child in the arthrotomy group (10%) had one predictor, two children (20%) had two predictors, two children (20%) had three predictors, and the remaining five children (50%) had four predictors. Among the arthroscopy group, three children (30%) had two predictors, three children (30%) had three predictors, and the remaining four children (40%) had four predictors.

Ultrasonographic examination of the affected hips revealed the presence of joint effusion in all the cases. Aspiration of the joint under ultrasonograpic control was successful for obtaining a synovial fluid sample for analysis and culture in all the cases. Total synovial aspirate leukocyte and differential neutrophil cell counts for both the arthrotomy and arthroscopy groups of patients are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Statistical analysis

The Student t-test and Chi-square tests were used for statistical analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant if the P value was less than 0.05 (P < 0.05).

Results

The causative pathogen could be isolated and cultured in nine cases among the arthrotomy group (90%) and in all cases of the arthroscopy group. Staphylococcus aureus was the most common causative microorganism in both the arthrotomy (50%) and arthroscopy (60%) groups (Tables 1, 3).

Table 3.

Causative microorganisms

| Arthrotomy group | Arthroscopy group | |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 5 (50%) | 6 (60%) |

| Streptococcus pneumonia | 2 (20%) | 3 (30%) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 0 | 1 (10%) |

| Escherichia coli | 1 (10%) | 0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 (10%) | 0 |

| No growth | 1 (10%) | 0 |

| Total no. of patients (hips) | 10 | 10 |

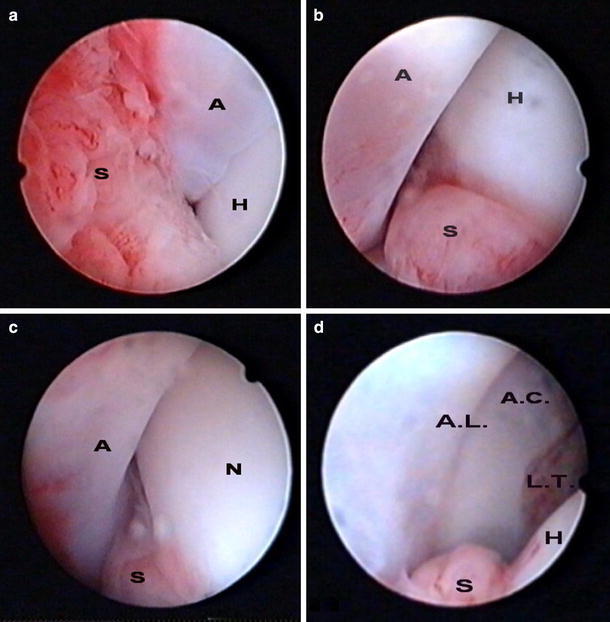

Pus or turbid fluid was drained from the joint in all patients of both groups. The joint cavity was washed out and inspected. Better visualization of the joint cavity could be achieved in the arthroscopy group. Varying degrees of synovitis were present in all cases of both groups. There was no evident articular cartilage damage in any case within both groups (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Arthroscopic views of the left hip joint in a four-year-old girl with acute septic arthritis. a Antero-superior view of the left hip and b anterior view of the left hip; both views show the femoral head (H) inside the acetabulum (A) with evident synovial tissue (S) inflammation. c Antero-inferior view of the left hip in adduction position showing the femoral neck (N) while the head is completely inside the acetabulum (A); part of the inflamed synovium (S) is seen in the inferior part of the view. d Anterior view of the acetabular cavity (A.C.) during distraction of the femoral head (H) showing the insertion of ligamentum teres (L.T.) and the acetabular labrum (A.L.); part of the inflamed synovium (S) is seen also in the inferior part of the view

All the children tolerated the procedures well with no intraoperative or postoperative complications. The suction drain was removed after a mean period of three days (range 2–5) in the arthrotomy group and 2.3 days (range 1–4) in the arthroscopy group. The difference was statistically insignificant (P = 0.136).

No patient in either group developed prolonged fever after removal of the drain. The mean duration of child’s hospital stay was 6.4 days (range 4–9) in the arthrotomy group and 3.8 days (range 3–6) in the arthroscopy group. The difference was statistically significant. (P < 0.0001).

In the arthrotomy group, antibiotics were given for a mean duration of 43.3 days (range 35–52) until recovery of the symptoms and the blood tests. In the arthroscopy group, antibiotics were given for a mean period of 45.6 days (range 37–53). The difference was not significant (P = 0.349).

Children were followed up in the out-patient clinic for a mean period of 23 months (range 14–39) in the arthrotomy group and for a mean period of 21.7 months (range 13–30) in the arthroscopy group.

Infection was eradicated in all patients of both the arthrotomy and arthroscopy groups with no recurrence of infection or development of osteomyelitis of the proximal femur.

At the end of follow up period, two children (20%) within the arthrotomy group and one child within the arthroscopy group (10%) were complaining of infrequent joint aches. However, these joint pains did not interfere with the activity of the children. One of the two children with joint aches within the arthrotomy group had slight limitation of hip abduction; the other child had full range of joint movement.

There was no limitation of the range of joint movement of the affected hip, as measured by a goniometer, in all directions in eight children in the arthrotomy group (80%). The range of hip abduction was less than that for the other, normal, hip by 10° in one child (who was also complaining of infrequent joint aches) and the range of hip external rotation in flexion was reduced by 10° compared with the contralateral hip in another child. There was no limitation of the range of joint movement of the affected hip in all directions in all children in the arthroscopy group. There was no joint positional deformity in all the children in both groups. There was no case of leg length discrepancy in either group by the end of follow up period.

At the latest follow up and according to Bennett’s clinical assessment criteria [12], seven children in the arthrotomy group (70%) had excellent clinical results and the remaining three children (30%) had good clinical results, due to occasional joint aches or slight limitation of joint movement; no child in this group had either fair or poor clinical results. In the arthroscopy group, nine children (90%) had excellent results and the remaining child (10%) had a good result, due to infrequent joint aches with no limitation of hip joint movement. Despite the tendency of having better clinical results among patients within arthroscopy group, the difference between the two groups regarding the final clinical results was not statistically significant (P = 0.852).

All the patients in both groups had normal radiographic appearance of the affected hip at final follow up and were graded as excellent according to Bennett’s anatomic (radiographic) assessment criteria [12].

Discussion

Acute septic arthritis of the hip in children is an orthopedic emergency that demands immediate accurate diagnosis and effective treatment to maximize the chances of a favorable long-term outcome, and to prevent life-long disabling sequelae [1–3, 13]. Therefore, there is a consensus of opinion that septic arthritis of the hip in children should be surgically drained immediately [1–3, 12–17, 21].

Open arthrotomy is still considered the standard treatment of patients with septic arthritis of the hip [1–3, 12, 13, 21].

Arthroscopic drainage of septic arthritis of the hip is a valid alternative to open arthrotomy. However, it has not been reported extensively despite its minimally invasive nature [4, 7–10, 28]. Hip arthroscopy is a technically demanding procedure in children. However, it is easier to do than in the adult population because of the relatively shallow joint and compliant soft tissues [4, 9]. This is especially true in the hands of orthopedic surgeons skilled in arthroscopy in this age group.

Some authors have reported preliminary results of arthroscopic treatment of septic arthritis in adults. Bould et al. [8] treated a 32-year-old man who had chronic septic arthritis of the hip by using arthroscopic irrigation. Blitzer [7] treated four patients with septic arthritis of the hip by arthroscopic drainage and copious fluid irrigation followed by placement of suction drain tubes through two arthroscopic portals. Yamamoto et al. [11] successfully treated four adults with septic arthritis of the hip joint by arthroscopic surgery and intraoperative high-volume irrigation. There was no recurrence of infection or other complications. Nusem et al. [6] used a three-portal arthroscopic technique for drainage, debridement, and irrigation in six patients with septic coxarthrosis. All patients had a rapid postoperative recovery, full range of motion of the affected hip, with no reported complications.

In treating septic arthritis of the hip in children, Chung et al. [9] performed arthroscopic lavage in nine patients, two to seven years old, followed by antibiotic therapy for three to six weeks postoperatively. This treatment was effective in ablating infection in all patients with no recurrences or complications attributable to the surgical procedure. The authors emphasized the value of large-bore arthroscopy instrumentation, high volume lavage, direct suction to remove joint debris, and postoperative suction drainage. Kim et al. [28] successfully treated an eight-year-old boy with septic arthritis of the hip by arthroscopic lavage. Still later, Kim et al. [10], reported results from arthroscopic debridement and drainage of septic arthritis of the hip in ten patients. Eight out these ten patients were 2–14 years old. The authors reported excellent results in all patients with no complications and they reported that arthroscopic irrigation was possible even in a two-year-old child using a 3-mm arthroscope [10].

The goal of the current study was to compare the results of open drainage (arthrotomy) versus arthroscopic drainage in the treatment of septic arthritis of the hip in children. The author is unaware of any study that compared the results of these two treatment modalities in septic arthritis of the hip in children.

There is a consensus of opinion that immediate accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment are the most important factors affecting the final outcome of septic arthritis of the hip in children [1–3, 12–17, 21]. Several authors have investigated the diagnostic tools for early clinical diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip [30–32]. Diagnosis was definite if pus was aspirated from the hip joint or bacteria were cultured from the joint aspirate. The diagnosis of joint sepsis is highly probable if the total synovial WBC count exceeds 50,000 cells per cubic millimeter of which more than 90% are polymorphonuleocytes [21]. Gram staining was shown to be an unreliable tool in early decision-making for patients requiring urgent surgical drainage and washout [33].

In this series, the microorganism was identified from specimens of synovial fluid aspirate or joint fluid taken during surgery in all cases except one in the arthrotomy group. In this case the diagnosis was made as the total synovial WBC count was 53,000 cells per cubic millimeter. In three patients within the arthrotomy group (30%) and four patients within the arthroscopy group (40%) the synovial WBC count was more than 50,000 cells per cubic millimeter. In the remaining 13 cases where the synovial WBC count was less than 50,000 cells per cubic millimeter, the bacterial culture from synovial fluid aspirate was positive.

Surgical drainage of the septic joint was performed as an emergency procedure immediately after ultrasonographically guided needle aspiration of the joint and the results of synovial fluid analysis were available.

In the arthrotomy group, the anterior approach was preferred over the posterior approach as it can be performed through a cosmetic incision, with minimal blood loss and it does not jeopardize the circumflex femoral vessels which provide the blood supply to the proximal femoral physis. In the arthroscopy group, better visualization of the joint cavity could be achieved during the drainage procedure.

Postoperative immobilization of the hip joint has been suggested by some authors in 40°–45° of abduction with a hip spica or skin traction for 4–6 weeks to prevent flexion adduction deformity which may predispose to subluxation or dislocation of the joint [2, 12, 21]. These concepts of treatment were challenged by Salter and his associates [34–36] who proved that prolonged immobilization with experimental joint sepsis resulted in loss of articular cartilage, especially at the points of direct contact. They also demonstrated that motion initiated after surgery had a beneficial effect on synovial fluid diffusion about the joint and on cartilage nutrition and had resulted in an accelerated healing of articular tissue lesions with more normal constituents of the ground substance in the collagen matrix [34–36]. Moreover, Katz et al. [37] documented the beneficial effect of early mobilization in children with septic arthritis. All the patients in our series were simply immobilized in bed with skin traction for a short period to reduce pain during the acute phase of the disease. At final follow-up, no patient evidenced a flexion adduction deformity or subluxation of the hip joint.

In agreement with other authors, the current study showed that children who had arthroscopic drainage of the septic hip had a significantly shorter duration of hospital stay than those who had arthrotomy drainage. This might be related to faster improvement of post-surgical pain with quicker recovery of both passive and active movement of the affected hip and earlier return of activity. This is due to the minimal invasive nature of arthroscopic drainage of the septic hip with minimal soft tissue disruption [4, 6, 10].

In contrast, recovery time was not affected by the method of joint drainage, whether arthroscopic or open arthrotomy. The absence of difference in the time until recovery of the symptoms and the blood tests between the two methods of treatment might be related to the possibility that recovery time is related to a greater extent to the pathological condition itself (which is the same in both groups) more than to the method of treatment itself.

At the end of the follow up period, both methods of joint drainage achieved the desired final outcome, i.e. eradication of infection with no recurrence or development of any of the known complications related to the process of hip joint sepsis or the method of joint drainage.

According to Bennett’s clinical assessment criteria [12], arthroscopic drainage achieved better final clinical outcome than open arthrotomy for children with acute septic arthritis of the hip joint. This statistically insignificant difference between both groups was related mainly to the presence of two children within the arthrotomy group complaining of infrequent joint aches, as compared with one child in the arthroscopy group, and the presence of minimal limitation of joint movement in two children within the arthrotomy group. These differences in the final clinical outcome might be related to the soft tissue dissection with subsequent scarring and fibrosis after open arthrotomy compared with the minimal invasive nature of arthroscopic drainage. Added to that is the minimal skin scaring associated with the arthroscopic procedure as compared with the incision scar in the arthrotomy procedure.

To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first controlled study in the literature to compare the results of open drainage (arthrotomy) versus arthroscopic drainage in the treatment of septic arthritis of the hip in children.

In conclusion, the results of this study support the consensus of opinion that the most important factor affecting the outcome of septic hips is early diagnosis and prompt treatment. Although immediate and complete drainage of the septic joint is more important than the method of drainage itself, the introduction of a less invasive procedure to achieve the desired goal with the same efficacy is always desirable especially in the pediatric population. Arthroscopic drainage proved to be an effective method for treating septic arthritis of the hip. It is associated with a shorter hospital stay, due to its minimal invasive nature with no soft tissue disruption. Added to that is the minimal skin scarring as compared to the unsightly scars associated with open arthrotomy, especially in the pediatric population.

Arthroscopic drainage of septic arthritis of the hip in children is a valid alternative to arthrotomy especially in uncomplicated cases diagnosed early and for those pediatric orthopedic surgeons skilled in arthroscopy in this patient population.

References

- 1.Farby G, Meire E. Septic arthritis of the hip in children: poor results after late and inadequate treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1983;3:461–466. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw BA, Kasser JR. Acute septic arthritis in infancy and childhood. Clin Orthop. 1990;257:212–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sucato DJ, Schwend RM, Gillespie R. Septic arthritis of the hip in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5:249–260. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199709000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeAngelis NA, Busconi BD. Hip arthroscopy in the pediatric population. Clin Orthop. 2003;406:60–63. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson RW. The septic knee-arthroscopic treatment. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:194–197. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(85)80011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nusem I, Jabur MK, Playford EG. Arthroscopic treatment of septic arthritis of the hip. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:902–e1–e3. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blizer CM. Arthroscopic management of septic arthritis of the hip. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:414–416. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(05)80315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bould M, Edwards D, Villar RN. Arthroscopic diagnosis and treatment of septic arthritis of the hip joint. Arthroscopy. 1993;6:707–708. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(05)80513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung WK, Slater GL, Bates EH. Treatment of septic arthritis of the hip by arthroscopic lavage. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:444–446. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SJ, Choi NH, Ko SH, Linton JA, Park HW. Arthroscopic treatment of septic arthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop. 2003;407:211–214. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200302000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto Y, Ide T, Hachisuka N, Maekawa S, Akamatsu N. Arthroscopic surgery for septic arthritis of the hip joint in 4 patients. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:290–297. doi: 10.1053/jars.2001.20664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett OM, Namnyak SS. Acute septic arthritis of the hip joint in infancy and childhood. Clin Orthop. 1992;281:123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CE, Ko JY, Li CC, Wang CJ. Acute septic arthritis of the hip in children. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:521–526. doi: 10.1007/s004020100280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Betz RR, Cooperman DR, Wopperer JM, Sutherland RD, White JJ, Jr, Schaaf HW, Aschliman MR, Choi IH, Bowen JR, Gillespie R. Late sequelae of septic arthritis of the hip in infancy and childhood. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10:365–372. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi IH, Pizzutillo PD, Bowen JR, Dragann R, Malhis T. Sequelae and reconstruction after septic arthritis of the hip in infants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1150–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vidigal Junior EC, Vidigal EC, Fernandes JL. Avascular necrosis as a complication of septic arthritis of the hip in children. Int Orthop. 1997;21:389–392. doi: 10.1007/s002640050192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hallel T, Salvati EA. Septic arthritis of the hip in infancy: end result study. Clin Orthop. 1978;132:115–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lunseth PA, Heiple KG. Prognosis in septic arthritis of the hip in children. Orthop Clin North Am. 1979;139:81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson NI, Di Paola M. Acute septic arthritis in infancy and childhood. 10 years’ experience. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68:584–587. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.68B4.3733835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrey BF, Bianco AJ, Jr, Rhodes KH. Suppurative arthritis of the hip in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:388–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nade S. Acute septic arthritis in infancy and childhood. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1983;65:234–241. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.65B3.6841388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paterson DC. Acute suppurative arthritis in infancy and childhood. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970;52:474–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kocher MS, Zurakowski D, Kasser JR. Differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children: an evidence-based clinical prediction algorithm. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1662–1670. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199912000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss SG, Schweitzer ME, Jacobson JA, Brossmann J, Lombardi JV, Dellose SM, Coralnick JR, Standiford KN, Resnick D. Hip joint fluid: Detection and distribution at MR imaging and US with cadaveric correlation. Radiology. 1998;208:43–48. doi: 10.1148/radiology.208.1.9646791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Givon U, Liberman B, Schindler A, Blankstein A, Ganel A. Treatment of septic arthritis of the hip joint by repeated ultrasound-guided aspirations. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:266–270. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200405000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kocher MS, Lee B. Hip arthroscopy in children and adolescents. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kocher MS, Kim YJ, Millis MB, Mandiga R, Siparsky P, Micheli LJ, Kasser JR. Hip arthroscopy in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:680–686. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000161836.59194.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SJ, Choi NH, Kim HJ. Operative hip arthroscopy. Clin Orthop. 1998;353:156–165. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199808000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy utilizing the supine position. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:264–267. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(96)90028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beach R. Minimally invasive approach to management of irritable hip in children. Lancet. 2000;355:1202–1203. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Del Beccaro MA, Champoux AN, Bockers T, Mendelman PM. Septic arthritis versus transient synovitis of the hip, the value of screening laboratory tests. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1418–1422. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)80052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eich GF, Superti-Furga A, Umbricht FS, Willi UV. The painful hip: evaluation of criteria for clinical decision-making. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158:923–928. doi: 10.1007/s004310051243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faraj AA, Omonbude OD, Godwin P. Gram staining in the diagnosis of acute septic arthritis. Acta Orthop Belg. 2002;68:388–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salter RB, Bell RS, Keelay FW. The protective articular cartilage in acute septic arthritis: an experimental investigation in the rabbit. Clin Orthop. 1981;159:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salter RB. The physiologic basis of continuous passive motion for articular cartilage healing and regeneration. Hand Clin. 1994;10:211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salter RB, Bell RS, Keeley FW. The protective effect of continuous passive motion on living articular cartilage in acute septic arthritis: An experimental investigation in the rabbit. Clin Orthop. 1981;159:223–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz K, Goldberg I, Yosipovitch Z. Early mobilization in septic arthritis. 14 children followed for 2 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61:161–162. doi: 10.3109/17453679009006512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]