Abstract

Objectives To estimate how many people object to storage of biological samples collected in health care in Sweden and to their use in research and how many withdraw previous consent.

Design Cross sectional study of register data.

Setting Biobanks used in Swedish health care, 2005-6.

Population Data on refusal to consent were obtained for 1.4 million biobank samples per year from 20 of 21 counties.

Main outcome measures Rates of preliminary refusal to consent, confirmed refusal, and withdrawal of consent.

Results Patients refused consent to either storage or use of their samples in about 1 in 690 cases; about 1 in 1600 confirmed their decision by completing a dissent form. Rather than having the samples destroyed, about 1 in 6200 patients wanted to restrict their use. Of those who had previously consented, about 1 in 19 000 withdrew their consent.

Conclusions Refusal to consent to biobank research in Sweden is rare, and the interests of individuals and research interests need not be at odds. The Swedish healthcare organisation is currently obliged to obtain either consent or refusal to each potential use of each sample taken, and lack of consent to research is used as the default position. A system of presumed consent with straightforward opt out would correspond with people’s attitudes, as expressed in their actions, towards biobank research.

Introduction

Erosion of trust1 2 3 in health care and medical science could have severe consequences for medical research.4 5 6 Some studies, however, do not support these concerns.4 7 8 9 10 A recent overview of international surveys found that at least 80% of people are willing to donate biological material for research.11 Willingness might be even higher in Sweden.12 13 14 Most Swedes seem to prefer general, one time consent in this context.5 15 People might be less concerned in their daily life about risks entailed by biobank research than they claim to be in surveys.

We determined the extent to which Swedish patients refused consent to storage or restricted the use of samples taken in public health care in 2005 and 2006; whether this poses an actual threat to biobank research; and whether trust in biobank research associated with Swedish health care is eroding.

Methods

Our targets were biobanks used in health care across the country. We did not include biobanks used exclusively for research or material from blood donations, autopsies, and fetal and infant screening.

Patients can express preliminary refusal to consent either when samples are taken or later by contacting the county’s biobank coordinator. In either case, refusalmust be confirmed by submitting a “dissent form” specifying the nature of the refusal (to storage, research, or some particular use). We asked biobank registers across the country for data on confirmed refusal toconsentand the number of laboratory referrals, which is equal to or less than the number of samples, in 2005 and 2006. We obtained full data for 13 of 21 counties, and partial coverage for seven; one county was unable to comply with the request.

Data were separated into series by sample type (for example, histopathological biopsies and cervical screening smears) and geographical location. Variables were expressed as percentages of the number of referrals. For each calculation, we excluded those and only those sample series for which the numerator was missing. We detected changes in overall ratios over time with χ2 test with continuity correction. We did not test for differencesseries by series, because they varied almost 700-fold in size.

Results

During 2005-6, about 1 in 690 potential donors expressed preliminary refusal to consent. Of these, about halfconfirmed their decision. A quarter of those who confirmed their refusal wanted to restrict the use of samples rather than having them destroyed, and 1 in 19 000 patients who initially consented withdrew their consent. The table summarises the main findings .

Refusal to consent to storage and use of biobank samples in Sweden in 2005 and 2006

| Sample series included* | 2005 | 2006 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | Rate in % (95% CI) | IQR for rate | Rate | Rate in % (95% CI) | IQR for rate | |||

| Preliminary refusal to consent | 72 | 1656/1 191 176 | 0.139 (0.132 to 0.146) | 0.031-0.123 | 1806/1 208 717

|

0.149 (0.143 to 0.156) | 0.022-0.097 | |

| Confirmed refusal to consent | 83 | 954/1 442 998 | 0.066 (0.062 to 0.070) | 0.000-0.075 | 888/1 466 659

|

0.061 (0.057 to 0.065) | 0.007-0.056 | |

| Specific refusal to consent | 79 | 224/1 401 572 | 0.016 (0.014 to 0.018) | 0.000-0.019 | 234/1 424 517

|

0.016 (0.014 to 0.019) | 0.000-0.017 | |

| Withdrawal of consent | 69 | 66/1 168 634 | 0.0056 (0.0043 to 0.0070) | 0.0000-0.0061 | 58/1 194 676

|

0.0049 (0.0036 to 0.0061) | 0.0000-0.0049 | |

| Unable to consent | 73 | 2469/1 218 372 | 0.20 (0.19 to 0.21) | 0.00-0.23 | 3639/1 239 765

|

0.29 (0.28 to 0.30) | 0.00-0.09 | |

| System error | 74 | 4049/1 213 496 | 0.33 (0.32 to 0.34) | 0.00-0.02 | 2376/1 236 391

|

0.19 (0.18 to 0.20) | 0.00-0.00 | |

IQR=interquartile range.

*Not all 83 sample series (groups of samples by type and geographical location) had data for each variable. Several rates fall outside corresponding interquartile ranges, which reflects presence of influential outliers.

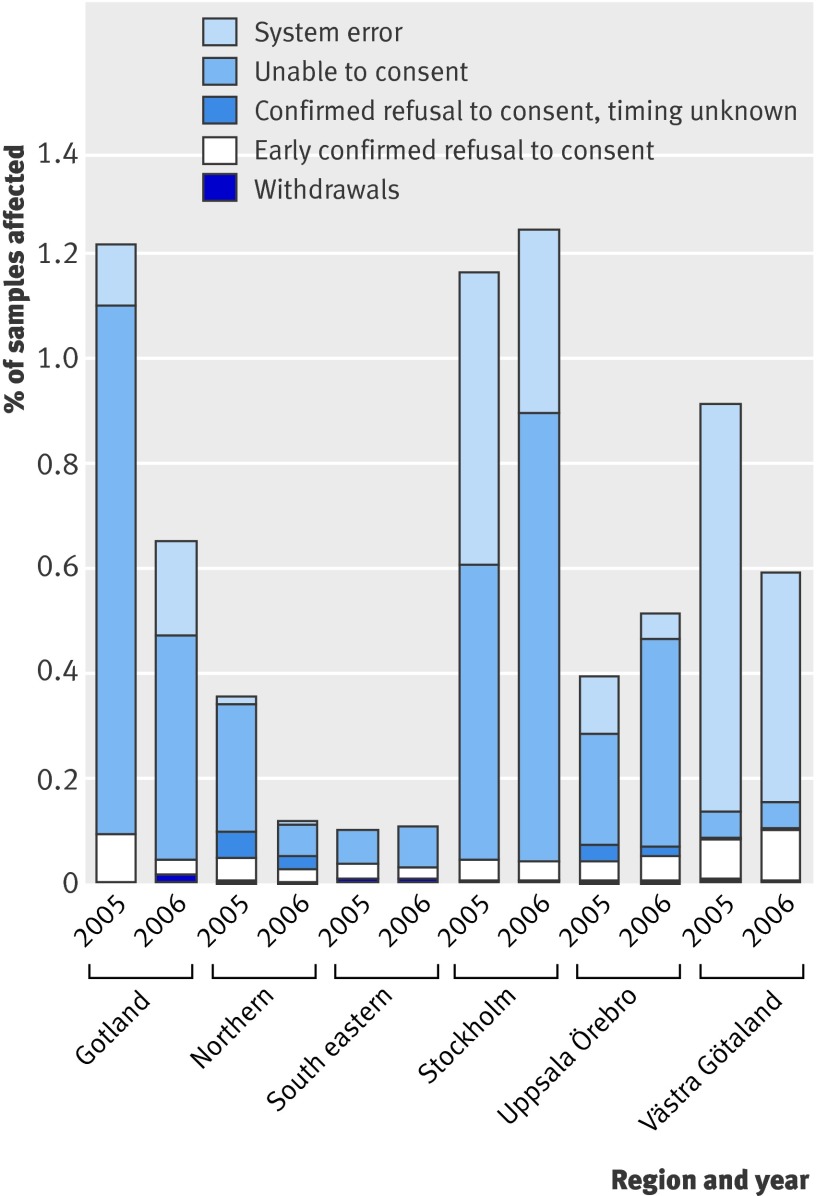

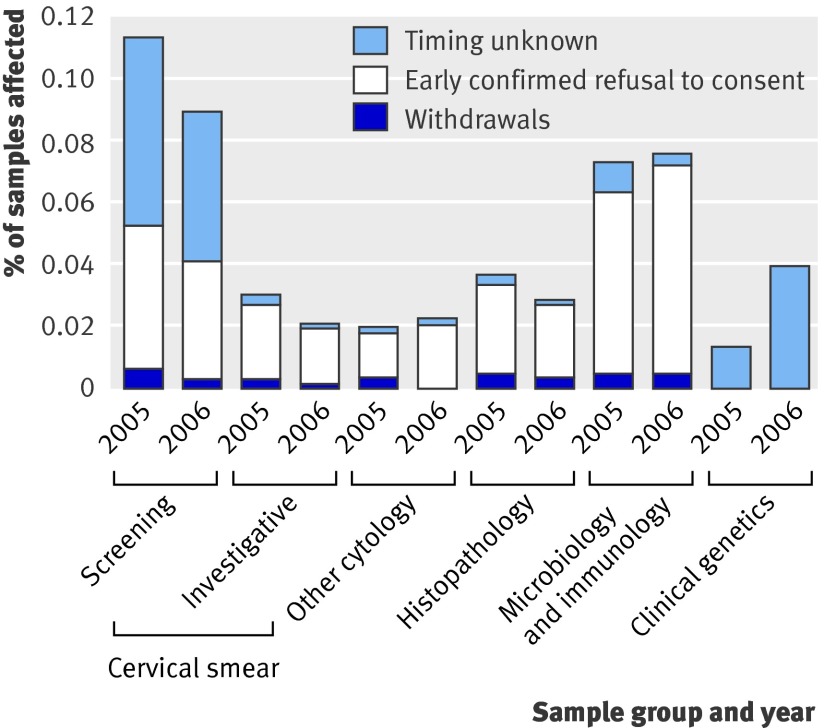

The main causes of “drop out” from future research (fig 1) were inability to consent (0.25%) and system errors (0.26%); the former increased (from 0.20% to 0.29%, P<0.001) from 2005 to 2006, while the latter dropped dramatically (from 0.33% to 0.19%, P<0.001) (table). Differences between regions can be explained by variations in follow-up practices and errors in reporting (for example, using the “inability to consent” category for indecisive patients or use of obsolete referral forms). Between sample types, refusal to consent was most common in the cervical screening subgroup (0.10%; fig 2).

Fig 1 Data from all 83 series per year. Not every series had data on system errors and inability to consent; missing values have been extrapolated. Not all registers specified whether patients refused consent early or late, so some withdrawals might be hidden in the “timing unknown” category

Fig 2 Data from 73 series per year that contained single, predefined sample types. Patients most likely to refuse consent were women undergoing screening for precancerous changes in cervix. In the clinical genetics category, interpretation is difficult because of small number of referrals (<8000/year); in absolute numbers, bars represent one and three cases of dissent, respectively. Other categories are larger (from 48 000 to >500 000 samples/year)

Preliminary rates of refusal to consent were particularly high in one pathology laboratory (794/207 866 (0.38%) in 2005 and 902/210 980 (0.43%) in 2006); however, only a tenth of these patients confirmed their decisions. Regarding confirmed refusal, we identified extreme outliers in two small series of seminal fluid samples (8/307 (2.6%) in 2005 and 8/403 (1.9%) in 2006).

Discussion

Fewer than 700 in one million Swedes actively oppose storage of or research using biobank samples collected in routine health care. Most of them refuse consent to storage, which is consistent with previous findings that privacy is important whereas the purpose of research is a lesser concern.11 15 16 The threat posed to quality of research is arguably minimal.

We believe that our results, although not necessarily generalisable to other contexts or cultures, are representative of patients in Sweden. The geographic coverage was sufficient. The age distribution might be skewed as elderly people are more frequent consumers of health care. Even among young to middle aged women in the cervical screening subgroup, however, the rates of refusal to consent were only about 0.1%.

One concern has been that refusal to consentcould be underestimated if several samples requiring separate referrals are taken in one session but the patient submits only one form to cover them all. While such a distortion might affect serological examinations, it is probably less pronounced for the other sample types.

Many people are unfamiliar with biobanks and might be underinformed about their rights and the possible implications of storing biological material. Still, people are becoming increasingly well informed through other channels, such as television, newspapers, the internet, and posters in waiting rooms. If people were concerned about their samples, we would expect more of them to refuse consent over time. Because of the short time frame our results do not exclude the possibility of such a trend, but neither do they support it.

Trust in health care and research

While our results tell us what patients do, they may indicate little of what they think. Surveys based on hypothetical situations, though with problems of their own,17 18 might provide more reliable measures of trust. On the other hand, if we believe that there is a connection between attitudes of trust and trusting behaviour, and, more particularly, assuming that most people with deeply felt distrust will not, given the choice, place trust,19 our results give us no reason to believe that distrust is widespread.

A complex and costly administration has been set up to protect the small minority of patients who do not want their samples to be stored in biobanks or used in research. The right to say “no” might be justified, no matter how small the minority utilising it,20 but the means chosen to protect it seem flawed. A system that consumes resources from public health care21 and imposes a bureaucracy with no benefits, while possibly still failing to inform people of their rights, is not likely to evoke the trust so urgently needed.22 Though informed consent in biobank research is a complex issue23 that warrants further research, the present study gives some reasons to consider an alternative system, where consent would be presumed, information readily available, and opting out straightforward.

What is already known on this topic

The right of patients to refuse consent to the use of their biological samples in research, and the right to withdraw previous consent, could harm quality of research

The threat could be even greater if trust in medical research and health care is eroding

What this study adds

During 2005 and 2006 in Sweden, for 1.4 million samples the rate of confirmed refusal to consent was 1 in 1600 for storage or use in research, and 1 in 19 000 people withdrew previous consent

These figures suggest no immediate threat to biobank research and no crisis of trust in research

This study was conducted as part of the AutoCure project of the EU Sixth Framework Programme.

Contributors: LJ collected and analysed data and wrote the paper. All authors contributed equally to study design and revision of critical intellectual content and approved the final version. LJ is guarantor.

Funding: AutoCure project within the EU Sixth Framework Programme.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2008;337:a345

References

- 1.Rönnberg P. Knappt varannan vuxen litar på forskare [Less than every other adult trusts scientists]. IVA-aktuellt, 2007.

- 2.Cousins G, McGee H, Ring L, Conroy R, Kay E, Croke D, et al. Public perceptions of biomedical research: a survey of the general population in Ireland. Dublin: Health Research Board, 2005.

- 3.Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust. Public perceptions of the collection of human biological samples. London: Medical Research Council, 2002.

- 4.Shore DA, ed. The trust crisis in healthcare: causes, consequences, and cures. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- 5.Kettis-Lindblad A, Ring L, Viberth E, Hansson MG. Perceptions of potential donors in the Swedish public towards information and consent procedures in relation to use of human tissue samples in biobanks: a population-based study. Scand J Public Health 2007;35:148-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asai A, Ohnishi M, Nishigaki E, Sekimoto M, Fukuhara S, Fukui T. Attitudes of the Japanese public and doctors towards use of archived information and samples without informed consent: preliminary findings based on focus group interviews. BMC Med Ethics 2002;3:e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fjaestad B, Olofsson A, Öhman S. Svenskarna och gentekniken: Rapport från 2002 års Eurobarometer om bioteknik [The Swedes and gene technology: report on year 2002 Eurobarometer on biotechnology]. Östersund: Institutionen för Samhällsvetenskap, Mitthögskolan, 2003.

- 8.Vetenskap & Allmänhet [Public & Science]. VA-rapport 2007:3 Allmänhetens syn på Vetenskap 2007 [VA-report 2007:3 Public views on Science 2007]. Stockholm: Vetenskap and Allmänhet, 2007.

- 9.O’Neill O. Autonomy and trust in bioethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- 10.Human Genetics Commission. Public attitudes to human genetic information. London: Human Genetics Commission, 2001.

- 11.Wendler D. One-time general consent for research on biological samples. BMJ 2006;332:544-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stegmayr B, Asplund K. Informed consent for genetic research on blood stored for more than a decade: a population based study. BMJ 2002;325:634-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilstun T, Hermeren G. Human tissue samples and ethics—attitudes of the general public in Sweden to biobank research. Med Health Care Philos 2006;9:81-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoeyer K, Olofsson BO, Mjorndal T, Lynoe N. The ethics of research using biobanks: reason to question the importance attributed to informed consent. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:97-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoeyer K, Olofsson BO, Mjorndal T, Lynoe N. Informed consent and biobanks: a population-based study of attitudes towards tissue donation for genetic research. Scand J Public Health 2004;32:224-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansson MG, Dillner J, Bartram CR, Carlson JA, Helgesson G. Should donors be allowed to give broad consent to future biobank research? Lancet Oncol 2006;7:266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willis G. Cognitive interviewing as a tool for improving the informed consent process. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2006;1:9-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pardo R, Midden C, Miller JD. Attitudes toward biotechnology in the European Union. J Biotechnol 2002;98:9-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kettis-Lindblad A, Ring L, Viberth E, Hansson MG. Genetic research and donation of tissue samples to biobanks. What do potential sample donors in the Swedish general public think? Eur J Public Health 2006;16:433-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sade RM. Research on stored biological samples is still research. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1439-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansson MG. For the safety and benefit of current and future patients. Pathobiology 2007;74:198-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansson MG. Building on relationships of trust in biobank research. J Med Ethics 2005;31:415-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibbons SMC, Kaye J. Governing genetic databases: collection, storage and use. King’s Law Journal 2007;18:201-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]