Abstract

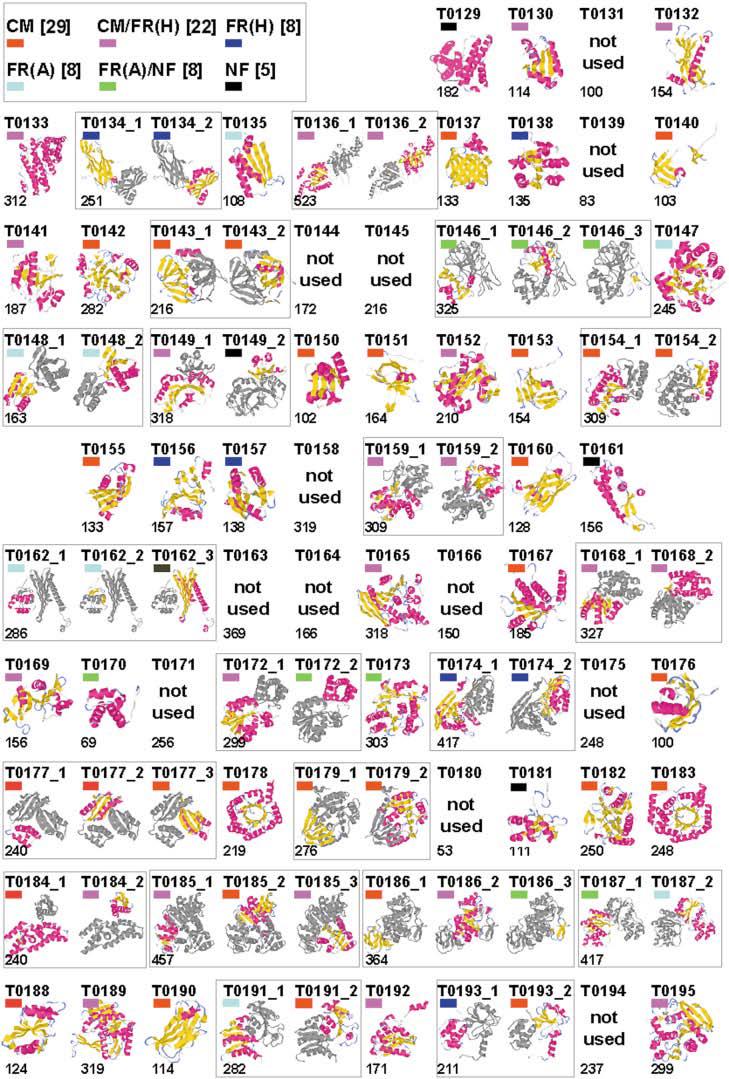

This report summarizes the Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP5) target proteins, which included 67 experimental models submitted from various structural genomics efforts and independent research groups. Throughout this special issue, CASP5 targets are referred to with the identification numbers T0129–T0195. Several of these targets were excluded from the assessment for various reasons: T0164 and T0166 were cancelled by the organizers; T0131, T0144, T0158, T0163, T0171, T0175, and T0180 were not available in time; T0145 was “natively unfolded”; the T0139 structure became available before the target expired; and T0194 was solved for a different sequence than the one submitted. Table I outlines the sequence and structural information available for CASP5 proteins in the context of existing folds and evolutionary relationships. This information provided the basis for a domain-based classification of the target structures into three assessment categories: comparative modeling (CM), fold recognition (FR), and new fold (NF). The FR category was further subdivided into homologues [FR(H)] and analogs [FR(A)] based on evolutionary considerations, and the overlap between assessment categories was classified as CM/FR(H) and FR(A)/NF. CASP5 domains are illustrated in Figure 1. Examples of nontrivial links between CASP5 target domains and existing structures that support our classifications are provided.

Definition of Domain Boundaries

Although assessment categories are named historically on the basis of the techniques used to generate structure predictions, targets are now classified on the basis the degree of sequence and structural similarity to known folds. The nature of such a classification scheme requires targets to be split into domains, because domains represent the basic units of folding and evolution. In CASP classification, multidomain protein targets often crossed assessment categories. For example, the two domains of target T0149 (E. coli hypothetical protein yjiA) exhibited very different relationships to proteins with known folds (Fig. 2). The sequence of the N-terminal domain [Fig. 2(A), white] placed it within the Nitrogenase iron protein-like family of P-loop NTPase structures [1cp2,1 Fig. 2(B)], whereas the sequence of the C-terminal domain did not resemble that of any existing fold sequence [Fig. 2(A), gray]. However, the C-terminal domain did bear some topological similarity to an Hpr-like fold [1pch,2 Fig. 2(C)]. Thus, proper classification of this target required defining appropriate domain boundaries and assigning the resulting domains to different categories.

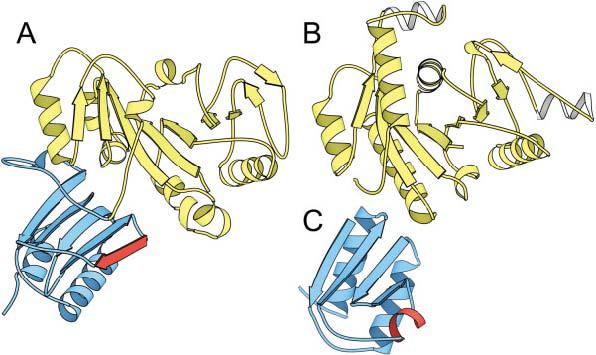

Fig. 2.

Target T0149: domains cross-classification categories. A: A molscript31 rendering of the two domains of target T0149 (E. coli hypothetical protein yjiA). The N-terminal domain is colored in white, and the C-terminal domain is colored in gray. The N-terminal domain (T0149_1) is homologous to (B), the Nitrogenase iron protein from C. pasteurianum (1cp2) and was assigned as CM/FR(H), whereas the C-terminal domain (T0149_2) was assigned to a new fold, although it displayed some topological similarity to (C) the histidine-containing phosphocarrier protein (1pch).

In addition to allowing a more discrete classification of CASP5 targets, domain parsing permitted us to provide a more accurate assessment of the structural quality of model predictions. When a domain rotation exists between an experimental structure and a model or template (e.g., T0159 with periplasmic binding protein 1gl2, known for 30° domain rotation on ligand binding3), a single superposition is not adequate to represent the similarities or differences between the two folds. Similarly, many automatic protein structure comparison methods provide lower scores for multiple-domain proteins than they do for the isolated domains. Accordingly, splitting targets into domains increased the scores assigned to CASP5 target predictions by automated evaluation approaches and ultimately provided a better estimation of group performance.

We defined CASP5 target domains manually, basing our judgment on the presence of a potentially independent hydrophobic core. We separated β-sheets when necessary to achieve such an arrangement. Precise domain boundaries were sometimes difficult to delineate. In such cases, we considered various aspects of the template domain structure: residue side-chain or backbone contacts within proposed domains, sequence or structural similarities to existing domains, and domains represented in predictor models as criteria for boundary selection. In total, 55 CASP5 target structures were divided into 80 independent domains, which corresponds to an increase from CASP4 (40 targets and 58 domains).

Examples of Difficult to Predict Domain Structures

Mutual domain arrangements are more challenging to predict than individual domain structures, especially when difficult domain organizations such as swaps or discontinuous boundaries exist. Domain swaps, defined as either an exchange of domains between protein chains or an exchange of secondary structural elements between domains, were found in several CASP5 target structures. Target T0140 represented a synthetic hybrid protein with a dimeric OB-fold formed by a β-hairpin swap. Although such swaps are becoming well-documented phenomena in protein structure, this arrangement remains virtually impossible to predict without having precedence in the existing pool of OB-folds. As such, we used portions of two chains in our definition of the domain boundaries for this target (see Table I).

TABLE I.

Overview of CASP5 Targets

| Target ID |

Lengtha | Name species | PDBb method |

Domains rangec | CASP classd |

Descriptione |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0129 | 182 | HI0817 H. influenzae |

— X-ray |

single | NF | Novel fold composed of seven helices. First four helices form a distorted up-and- down bundle, whereas the rest assemble as a 3-helical left-handed bundle. Helix 2 and helix 5 form a tight interaction. |

| T0130 | 114 | HI0073 H. influenzae |

— X-ray |

CM/FR(H) | Nucleotidyltransferase superfamily. Sequence finds PDB (18% 1fa0, Dali z score 5.0) with transitive PSI-BLAST. Compared to 1fa0, the structure contains generally shorter structural elements, loses an edge β-hairpin, and retains the active site. |

|

| T0131 | 100 | HI0857 H. influenzae |

— X-ray |

single | not used | Preliminary version of the structure. No side-chain assignments. Not used for assessment. |

| T0132 | 154 | HI0827 H. influenzae |

— X-ray |

single | CM/FR(H) | Thioesterase superfamily member. Sequence finds 4-Hydroxybenzoyl CoA Thioesterase (16%, 1bvq, Dali z score 13.4) with transitive PSI-BLAST. |

| T0133 | 312 | HIP1R N-terminal domain rat |

— X-ray |

single | CM/FR(H) | α/α superhelix fold, same family as N- terminal domain of phosphoinositide- binding clathrin adaptor (13% 1hg5). |

| T0134 | 251 | δ-adaptin appendage domain human |

— X-ray |

T0134_1:A878- A1006 T0134_2:A1007- A1112 |

FR(H) FR(H) |

Shares domain structure with remote homologue clathrin adaptor appendage domain (12% 1qts). Homology inferred from structural similarity (Dali z score 19.1). N-terminal domain related to g1-adaption ear domain (1 gyu). |

| T0135 | 108 | Boiling stable protein P. tremula |

— X-ray |

single | FR(A) | Ferredoxin-like fold analog. Contains broken helix with conserved residues not found in current ferredoxin-like fold superfamilies. A tight dimer with two β-sheets forming a barrel, dimer structure is similar to C-terminal domains of Lrp/AsnC-like transcriptional regulator (1i1g) and Muconalactone isomerase (1mli). eEF- 1beta-like domain (6% 1b64) aligns with Dali z score 3.2. |

| T0136 | 523 | Transcarboxylase 12S subunit P. shermanii |

1on3 1on9 X-ray |

T0136_1: E4-E259 T0136_2: E260-E523 |

CM/FR(H) CM/FR(H) |

Duplication of a Clp/crotonase-like domain. Two domains are closer to each other than to any known structure and share an additional ααββ-unit at the N-terminus. Each domain finds PDB (12–13%, 1dub) with transitive PSI- BLAST. Closest PDB structure 1nzy, Dali z score 14.1 and 13.2 for domains 1 and 2. |

| T0137 | 133 | Fatty acid binding protein E. granulosus |

1o8v X-ray |

single | CM | Fatty acid-binding protein family (43% 2ans). |

| T0138 | 135 | KaiA N-terminal domain S. elongatus |

1m2e 1m2f NMR |

single | FR(H) | Flavodoxin-like fold, CheY-like superfamily (19% 1kgs). Homology interference based on structural similarity (Dali z score 13.2). |

| T0139 | 83 | Fragmentation factor/Caspase inhibitor DNase domain human |

1koy NMR |

single | not used | Novel fold with irregular array of four helices. Some topological similarity to existing structures (e.g., 1a9x_A:419- 481). Information about the structure available before the target expired. Not used in assessment. |

| T0140 | 103 | 1B11 synthetic protein | — X-ray |

single, composite of 2 chains B18-B74, A74- A102 |

CM | Synthetic protein composed of cold shock protein A (N-terminal) and E. coli 30S ribosomal subunit protein S1 (C- terminal). Although each parent structure forms an OB-fold, the synthetic protein forms an OB-fold-like swapped-dimer. |

| T0141 | 187 | AmpD C. freundii |

1iya NMR |

single | CM/FR(H) | Homologue of T7 lysozyme (26% 1lba). Unexpected structural differences in active site. |

| T0142 | 282 | Nitrophorin C. lectularius |

— X-ray |

single | CM | DNaseI-like fold, Inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase family (26% 1i9z). |

| T0143 | 216 | V8 protease S. aureus |

— X-ray |

T0143_1:1-20, 116-216 T0143_2:21-115 |

CM CM |

Trypsin-like serine protease composed of two domains treated as a single unit (28% 1agj). |

| T0144 | 172 | CYP protein L. luteus |

— X-ray |

— | not used | N/A |

| T0145 | 216 | Gliotactin C-terminus D. melanogaster |

— X-ray |

— | not used | No coordinates; “natively unfolded” protein. |

| T0146 | 325 | ygfZ E. coli |

— X-ray |

T0146_1:A1- A24, A114-A196 T0146_2: A25-A113 T0146_3: A244-A299 |

FR(A)/NF FR(A)/NF FR(A)/NF |

Three domains: Domains 1 and 2 in tight contact and represent a potential duplication of a ferredoxin-like unit with an additional β-strand inserted at the edge of the β-sheet. Domain 1 is circularly permuted with respect to domain 2. No side-chain assignments for domain 3. Domains 2 and 3 connected by a sequence-conserved linker. |

| T0147 | 245 | ycdX E. coli |

1m65 1m68 X-ray |

single | FR(A) | PHP domain, a seven-stranded version of a TIM β/α-barrel fold. Possible remote homologue of metallohydrolases (12% 1k6w, Dali z score 8.1), with which it shares a metal-binding site. |

| T0148 | 163 | HI1034 H. influenzae |

1in0 X-ray |

T0148_1:A2-A9, A101-A163 T0148_2: A10-A100 |

FR(A) FR(A) |

Tandem repeat of a ferredoxin-like fold with swapped N-terminal strands. Each domain is a possible remote homologue of Ribosome recycling factor α+β domain (11%, 15% 1ek8). |

| T0149 | 318 | yjiA E. coli |

1nij X-ray |

T0149_1: A2-A202 T0149_2: A203-A318 |

CM/FR(H) NF |

Two domains: N-terminal Nitrogenase iron protein family (17% 1j8m). C- terminal novel fold with some structural similarity to 1ah6, 1ebf_B: 149-337, 1ptf and target T0187_1. |

| T0150 | 102 | Ribosomal protein L30E T. celer |

1h7m X-ray |

single | CM | L30e/L7ae ribosomal protein family (34% 1ck2). |

| T0151 | 164 | Single-strand binding protein M. tuberculosis |

— X-ray |

single | CM | ssDNA-binding protein, OB-fold (30% 1qvc). |

| T0152 | 210 | Hypothetical protein Rv1347c M. tuberculosis |

— X-ray |

single | CM/FR(H) | Acyl-CoA N-actyltransferase (NAT) family (15% 1ild). Typical for this family b-bulge in the active site lacks in this protein leading to a different shape of the β-sheet. |

| T0153 | 154 | dUTPase M. tuberculosis |

1mq7 X-ray |

single | CM | dUTPase, beta-clip fold (35% leu5). |

| T0154 | 309 | Pantothenate synthetase M. tuberculosis |

1mop- X-ray |

T0154_1: A3-A187 T0154_2: A188-A290 |

CM CM |

PanC, Adenine nucleotide α-hydrolase- like fold (35%, 49% iho), proteins share domain structure. |

| T0155 | 133 | Probable dihydroneopterin aldolase M. tuberculosis |

— X-ray |

single | CM | 7,8-dihidroneopterin aldolase, T-fold (33% 1dhn). |

| T0156 | 157 | Probable SAM-dependent methyltransferase M. tuberculosis |

— X-ray |

single | FR(H) | Phosphohistidine domain superfamily, the “swiveling” domain fold (14% 1 dik, Dali z score 7.5). Homology inferred from structural similarity. |

| T0157 | 138 | yqgF E. coli |

— X-ray |

single | FR(H) | Ribonuclease H-like superfamily (15% 1hjr Dali z score 9.6). Homology inferred from the presence of described RNaseH motifs. |

| T0158 | 319 | Actyl esterase E. coli |

— X-ray |

— | not used | N/A |

| T0159 | 309 | Glycine betaine-binding protein E. coli |

— X-ray |

T0159_1:X1- X91, X234-X309 T0159_2: X92-X233 |

CM/FR(H) CM/FR(H) |

Periplasmic-binding protein I-like superfamily. Two domains with different relative orientation than closest homologue (8% 1gr2). Transitive PSI-BLAST searches establish homology. |

| T0160 | 128 | VAP-A protein rat |

— X-ray |

single | CM | Major sperm protein family, Immunoglobulin-like fold (22% 2msp). |

| T0161 | 156 | HI1480 H. influenzae |

— X-ray |

single | NF | New fold, α-helical array capped with a curved three-stranded β-sheet. |

| T0162 | 286 | F-actin capping protein a-1 subunit chicken |

1izn X-ray |

T0162_1: A7-A62 T0162_2: A63-A113 T0162_3: A114-A281 |

FR(A) FR(A) NF |

Three domains: N-terminal three-helical bundle, middle possible rubredoxin-like zinc finger that lost zinc ligands (9% 1rfs), C-terminal novel fold five- stranded meander flanked by two helices. |

| T0163 | 369 | Glycin oxidase B. subtilis |

— X-ray |

— | not used | N/A |

| T0164 | 166 | C20 | — X-ray |

— | not used | cancelled |

| T0165 | 318 | Cephalosporin C deacetylase B. subtilis |

117a X-ray |

single | CM/FR(H) | α/β-hydrolase superfamily (18% 1a8s). |

| T0166 | 150 | SLYA E. faecalis |

— X-ray |

— | not used | cancelled |

| T0167 | 185 | Hypothetical cytosolic protein yckF B. subtilis |

1m3s X-ray |

single | CM | SIS domain (39% 1jeo). |

| T0168 | 327 | Glutaminase B. subtilis |

1mki X-ray |

T0168_1:A1- A68, A210-A327 T0168_2: A69-A209 |

CM/FR(H) CM/FR(H) |

Domain structure shared by β- Lactamase/D-ala carboxypeptidase superfamily (7% 1fof). Found by transitive PSI-BLAST. |

| T0169 | 156 | yqjY B. subtilis |

1mk4 X-ray |

single | CM/FR(H) | N-acetyl transferase (NAT) family (9% 1bo4). |

| T0170 | 69 | FF domain of HYPA/FBP11 human |

1h40 NMR |

single | FR(A)/NF | Three-helical bundle capped by a 3_10 helix, new fold, structural similarity to Phosphatase 2C C-terminal domain (1a6q:297-368) and three-helical DNA/ RNA-biding bundles. |

| T0171 | 256 | Protein BioH E. coli |

1m33 X-ray |

— | not used | N/A |

| T0172 | 299 | Conserved hypothetical protein MRAW T. maritima |

1m6y 1n2x X-ray |

T0172_1:A2- A115, A217-A294 T0172_2: A116-A216 |

CM/FR(H) FR(A)/NF |

SAM-dependent methyltransferase (16% 1jg2) with an inserted SAM-like fold domain (15% 1cuk). |

| T0173 | 303 | Mycothiol deacetylase M. tuberculosis |

— X-ray |

single | FR(A)/NF | Novel Rossmann-like α/β fold with topological similarity to SAM methyltransferases but distinct curvature of the β-sheet. |

| T0174 | 417 | Protein XO1-1 C. elegans |

1mg7 X-ray |

T0174_1:B8- B28, B199-B374 T0174_2: B39-B198 |

FR(H) FR(H) |

GHMP kinase family, homology inferred from structural similarity (9% 1kvk, Dali z score 18.5). |

| T0175 | 248 | Hypothetical protein yjhP E. coli |

1nkv X-ray |

— | not used | N/A |

| T0176 | 100 | Hypothetical protein yggU E. coli |

1n91 X-ray |

single | CM | Close homologue of hypothetical protein MTH637 (26% 1jrm). |

| T0177 | 240 | Hypothetical protein HP0162 H. pylori |

1mw7 X-ray |

T0177_1: A21-A77 T0177_2: A78-A130, A206-A240 T0177_3: A131-A205 |

CM CM CM |

YebC-like family (30% 1kon), proteins share the domain structure. |

| T0178 | 219 | Deoxyribose-phosphate aldolase A. aeolicus |

1mzh X-ray |

single | CM | Deoxyribose-phosphate aldolase DeoC, TIM-barrel (27% 1jcl). |

| T0179 | 276 | Spermidine synthase homolog B. subtilis |

liy9 X-ray |

T0179_1:A2-A57 T0179_2: A58-A275 |

CM CM |

Spermidine synthase (43% 1 inl), proteins share domain structure, SAM- dependent methyltransferase homologue. |

| T0180 | 53 | Hypothetical protein MTH467 M. thermoautotrophicum |

— NMR |

— | not used | N/A |

| T0181 | 111 | Hypothetical protein YHR087w S. cerevisiae |

1nyn X-ray |

single | NF | New fold, curved antiparallel β-sheet with 4 α-helices on one side, unusual topology. |

| T0182 | 250 | TM1478 T. maritima |

1o0x X-ray |

single | CM | Methionine aminopeptidase (42% 2mat). |

| T0183 | 248 | TM1559 T. maritima |

1o0y X-ray |

single | CM | Deoxyribose-phosphate aldolase DeoC, TIM-barrel (30% 1jcl). |

| T0184 | 240 | TM1102 T. maritima |

1o0w X-ray |

T0184_1: B1-B165 T0184_2: B166-B236 |

CM CM/FR(H) |

Two domains: N-terminal RNase III endonuclease domain (35% 1jfz). C- terminal dsRNA-binding domain (26% 1di2). |

| T0185 | 457 | TM0231 T. maritima |

1j6u X-ray |

T0185_1: A1-A101 T0185_2: A102-A298 T0185_3: A299-A446 |

CM/FR(H) CM CM/FR(H) |

MurD-like family (22% 3uag), proteins share domain structure. P-loop in the middle domain. |

| T0186 | 364 | TM0814 T. maritima |

1o12 X-ray |

T0186_1:A1- A44, A331-A363 T0186_2: A45-A256, A293-A330 T0186_3: A257-A292 |

CM CM/FR(H) FR(A)/NF |

Metallohydrolase superfamily, TIM β/α- barrel catalytic domain (domain 2, 25% 1gkp), shares “composite” domain with some homologues (domain 1, 13% 1gkp). Interesting dwarf insertion domain, unique to this protein, potential deteriorated rubredoxin-like zinc finger (domain 3, 13% 1kqs). |

| T0187 | 417 | TM1585 T. maritima |

1o0u X-ray |

T0187_1:A4- 2A2, A250-A417 T0187_2: A23-A249 |

FR(A)/NF FR(A) |

Two domains: N-terminal structurally similar to Cobalt precorrin-4 methyltransferase C-terminal domain (8% 1cbf), C-terminal Rossmann-type fold (11% 1gpj). T0187_1 shares some topological similarity with T0149_2. |

| T0188 | 124 | TM1816 T. maritima |

1o13 X-ray |

single | CM | Close homologue of hypothetical protein MTH1175, RNaseH-like fold (31% 1eo1). |

| T0189 | 319 | TM0828 T. maritima |

1o14 X-ray |

single | CM/FR(H) | Ribokinase-like family (14% 1rk2). |

| T0190 | 114 | Transthyretin-related protein E. coli |

— X-ray |

single | CM | Prokaryotic homologue of transthyretin (31% 1dvx). |

| T0191 | 282 | Shikimate 5-dehydrogenase M. jannaschii |

1nvt X-ray |

T0191_1:A1- A104, A248-A282 T0191_2: A105-A247 |

FR(A) CM |

Two different domains, N-terminal anticodon-binding domain-like fold (7% 1ati), C-terminal NAD(P)-binding Rossmann superfamily (22% 1gpj). |

| T0192 | 171 | Spermidime/Spermine acetyltransferase human |

— X-ray |

single, composite of 2 chains: 2-153 (first chain), 154-171 (second chain) |

CM/FR(H) | N-acetyl transferase (NAT) family, (16% 1qsm), domain-swapped last strands. |

| T0193 | 211 | AT-rich DNA binding protein T. aquaticus |

— X-ray |

T0193_1:A1-A78 composite of 2 chains T0193_2: A79-A187 (first chain), B188-B209 (second chain) |

FR(H) CM |

Two different domains, N-terminal 3- helical bundle, winged HTH motif (29% 1j5y), PSI-BLAST detects structural similarity with E-values below threshold. C-terminal NAD(P)-binding Rossmann superfamily (17% 1ofg), domain-swapped last helix; closest template was given away as “Additional Information.” |

| T0194 | 237 | Hypothetical protein Y450 M. pneumoniae |

— X-ray |

— | not used | The structure was solved not for the target sequence but for its homologue (~20%). Not used in assessment. |

| T0195 | 299 | Hypothetical esterase in SMC3-MRPL8 intergenic region S. cerevisiae |

— X-ray |

single | CM/FR(H) | α/β-Hydrolase superfamily (18% 1jjf). |

Length of the sequence provided for prediction.

PDB identifier for the structure is given, where known. In some cases, the structure is not yet published and has not been deposited with PDB.

Domain definitions refer to residue numbers in the 3D coordinate structure provided by the experimentalists.

See text for discussion of class.

Brief discussion of the structure within the context of existing protein fold classifications, with possible evolutionary connections (see text for discussion). Where simple sequence similarity searches of the target against representative sequences of structures in the PDB yielded an unambiguous match, the percentage similarity and sample PDB identifiers are given.

Three different CASP5 targets (T0152, T0169, and T0192) belong to the Acyl-CoA N-acyltransferase family. This family contains members that exist as either an independent fold (i.e., 1cjw4) or a β-strand-swapped dimer (i.e., 1qsm5). It is of interest that one of the target structures (T0192) formed a swapped-dimer, whereas the other two (T0152 and T0169) did not. Although prediction of such a swap was conceivable in this case, we used portions of two chains in our definition of the domain boundaries. Predictions could then be compared with either the original protein chain (β-strand extended into space) or the defined domain (β-strand completing the fold).

The second type of difficult domain organization includes structures that contained discontinuous domain boundaries with respect to their primary sequence structure. Such an arrangement may result from a domain insertion into the middle of an existing fold or from a swap of secondary structural elements between domains. Target T0148 provides an excellent example of a CASP5 target with discontinuous domain boundaries. This target contained a tandem repeat of ferredoxin-like fold domains with swapped N-terminal β-strands.

Evolution-Based Domain Classification

The main goal of CASP5 classification was to place target domains among existing structures so that predictions could be assessed according to three main categories: comparative modeling, fold recognition, and new fold. To accomplish this task, we used sequence and structure similarity measures to find the closest neighbors (templates) to target domains and a classification scheme similar to that defined by the Structural Classification of Proteins (SCOP) database.6 This procedure allowed us to hypothesize about the evolutionary relationships between CASP5 targets and existing protein structures.

To evaluate the similarities of CASP5 targets to proteins of known folds, we used a combination of sequence/profile and structure database-searching approaches. All domains identified with sequence-based methods were assigned to the comparative modeling assessment category (CM). In general, simple BLAST7 searches (E-value cutoff 0.005) of the nonredundant database (NR, September 18, 2002) identified close homologues of target sequences (26 domains). Sequence profile searches using multiple iterations (up to 5) of PSI-BLAST8 (E-value cutoff 0.005) identified more distant homologs (17 domains), and transitive PSI-BLAST searches (E-value cutoff 0.02 with manual filtering) initiated from a number of sequences found to be homologous to the initial target sequence identified additional remote homologues (8 domains). For all of these cases, structural similarity to identified folds in the Protein Data Bank9 was confirmed with inspection of Dali structure superpositions.10,11 Unusual structural differences revealed in this inspection between the targets and templates with detectable sequence similarities (T0141 with 1lba12 and T0152 with 1cjw4) are noted in Table I.

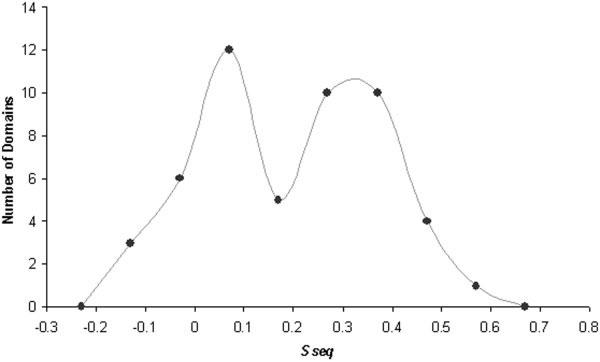

The CM domains identified through these sequence/profile-based methods represent a significant portion of the CASP5 targets (51 of 80 domains) and cover a broad range of sequence similarities to PDB templates (some identified with simple BLAST, and some identified with transitive PSI-BLAST searches). By using a measure of sequence similarity to identified PDB templates described the CASP5 fold recognition assessment (Sseq),13 the target domains assigned to this single category tended to fall into two groups (see bimodal distribution, Fig. 3). These two groups correspond to close homologues (higher Sseq group, Fig. 3) and remote homologues (lower Sseq group, Fig. 3). Generally, targets grouped within the close homologues identified template sequences with simple BLAST or with PSI-BLAST and represented either identical proteins from different species (orthologs) or similar proteins from the same SCOP families as the template proteins. Likewise, targets grouped within the remote homologues identified template sequences with PSI-BLAST or with transitive PSI-BLAST and belonged to the same SCOP superfamilies as the template proteins.

Fig. 3.

Classification of comparative modeling targets: similarity to templates. The numbers of domains that have similarity scores (Sseq) within the indicated bin ranges (x axis) are depicted as closed circles. A smoothed line connects the circles to illustrate the resulting bimodal distribution of the comparative modeling target domains.

The bimodal distribution of target domains illustrated in Figure 3 suggests a natural boundary between the comparative modeling assessment category and the fold recognition category. However, grouping the target domains into two discrete clusters based on this sequence similarity measure (Sseq) alone was difficult. To accomplish this task, we chose to include an additional measure of structural similarity to identified PDB templates (see fold recognition assessment article for a complete description13). The resulting two-dimensional scale defined a precise boundary between close homologues (29 CM domains) and remote homologues (22 CM/FR(H) domains), although it resulted in a significant overlap between the two assessment categories.

To classify the remaining targets (29 domains), we used Dali10,11 to search the PDB for protein structures with similar folds. We also used a secondary structure-based vector search program developed in our laboratory (unpublished) to identify more distant protein structures in the PDB that displayed similar topologies to the target folds. We combined these automated search programs with manual inspection and a general knowledge of protein folds to produce the final classification. For cases with identified structural similarities (24 domains), analogy between the target and template was assumed unless there was enough compelling evidence to hypothesize descent from a common ancestor (see examples below). For those cases without clear similarities to known structures, a classification of new fold was assigned (5 domains).

The overlap [FR(A)/NF] between the fold recognition category and the new fold category was defined on the basis of various criteria including general overall size and fold topology of the complete structure, length, and arrangement of individual secondary structural elements within the structure, and degree of partial similarities to existing folds. We asked the question: How well does an existing fold approximate this target domain? One of the more difficult targets to classify in this respect was the C-terminal domain of F-actin capping protein α-1 subunit (T0162_3). We classified this domain as NF, although the overall topology of the core was similar to that of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 (1u9a14). Each structure includes a five-strand meander flanked on one side by two α-helices. However, the flanking helices of the target domain (T0162_3) form a parallel interaction with a flat β-sheet, whereas those of Ubc9 interact in a perpendicular orientation due to a significant twist of the β-sheet. In addition, the secondary structural elements of Ubc9 are generally shorter in length than those of the target and include two additional C-terminal helices. Finally, Ubc9 represents an independent folding unit, whereas the extended target domain likely requires another subunit to form a compact structure.

Examples of Homologous Domains

In classifying individual CASP5 target domains, we sought to establish evolutionary relationships to existing folds wherever possible. First, we defined as a homologue any target whose sequence detected its corresponding template sequence using the various forms of PSI-BLAST. Target T0168, a glutaminase from B. subtilis, represents one of the most challenging sequence links established with use of these methods. By using transitive PSI-BLAST searches with two intermediate sequences, a hypothetical protein from P. aeruginosa (gi|15596835) and a 6-aminohexanoate-dimer hydrolase (gi|488342), this target glutaminase sequence was linked to sequences from the β-lactamase/D-ala carboxypeptidase superfamily (i.e., 3pte, 2blt, 1ci9). Members of this superfamily contain an α/β sandwich domain interrupted by a cluster of helices. The active site lies between these two domains and contains a conserved catalytic Ser-x-x-Lys motif.15-17 The presence of this motif in the glutaminase structure, along with the positioning of conserved residues within the defined active site cleft, further supported the presumption of homology for this target.

For those targets without detectable sequence similarity, we considered the degree of structural similarity to known folds (Dali z score above 918) and combined this information with additional structural and functional considerations as evidence for homology. Examples of such additional considerations included similarities in the organization of domain structure, the sharing of unusual structural features, the sharing of local structural motifs, or the placement of active sites. Six additional CASP5 target domains (T0134, T0138, T0156, T0157, T0174, and T0193_1) were classified as homologues to proteins with known folds based on these criteria.

Two of these CASP5 targets (T0134 and T0174) displayed considerable structural similarity (Dali z scores 19.1 and 18.5) to their respective templates (1qts19 and 1kvk20) while retaining an identical domain organization. Both the delta-adaptin appendage domain (target T0134) and its closest template, the clatherin adaptor appendage domain (1qts19), have an N-terminal immunoglubulin-like β-sandwich followed by a C-terminal clathrin adaptor appendage domain-like fold. Similarly, target T0174 (Protein XOl-1 from C. elegans) displays a two-domain structure analogous to that of its closest template, mevalonate kinase (1kvk20). Both structures include an N-terminal ribosomal protein S5 domain 2-like domain and a C-terminal ferredoxin-like domain.

Additional examples of notable structural similarity in the absence of detected sequence similarity included target T0138 and target T0156. The target T0138 KaiA N-terminal domain from S. elongates superimposed with a CheY-like superfamily member, the PhoB receiver domain from T. maritima (1kgs21), with a reasonable Dali z score (13.9). The structure of target T0156 had a less impressive Dali z score (7.5) when aligned with the “swiveling” domain of pyruvate phosphate dikinase (1 dik22). However, both structures included an identical topological arrangement of secondary structural elements comprising the three layers (β-β-α) of the “swiveling” domain fold. In addition, the two β-sheet layers of both the target domain (T0156) and the template domain (1 dik central domain) form a distinctive closed barrel (n = 7, S = 10). This unusual structural similarity compelled us to regard these two proteins as homologues.

Two CASP5 targets (T0193_1 and T0157) retained conserved motifs that distinguished important structural or functional aspects of their closest templates. The N-terminal domain of target T0193, an AT-rich DNA-binding protein from T. aquaticus, formed a three-helical bundle with a winged helix-turn-helix motif similar to that of the putative transcriptional regulator TM1602 N-terminal domain (1j5y9). PSI-BLAST detected the sequence of this structure (1j5y) with an E-value (0.85 over 47 residues) outside a reasonable threshold but with an alignment that matched the structural alignment. The target structure superimposed with the template structure (Dali z score 4.8), although residues corresponding to the “wing” were disordered. Target T0157, E. coli yqgF, retained identifiable structural motifs present in the ribonuclease H-like fold (i.e., RuvC resolvase 1hjr23). It is of interest that these motifs were already identified in an article describing the structural and evolutionary relationships of Holliday junction resolvases and related nucleases.24 Based on the presence of these motifs, this article predicted a preservation of the core RuvC secondary structure elements in the structure corresponding to the CASP5 target sequence T0157.

Finally, target T0147, E. coli YcdX, presented an unresolved case of potential homology to the TIM β/α barrel superfamily of metallo-dependent hydrolases. This target was previously defined as a PHP domain based on a detailed analysis of the domain conservation of two distinct classes of polymerases.25 Although no definitive structural prediction for the PHP domain superfamily was presented in the report, the authors suggested a link to the metal-dependent hydrolase superfamily based on the presence of a conserved metal binding site motif (HXH) and the results of multiple alignment-based database threading.25

It is interesting that metal-dependent hydrolases such as cytosine deaminase (1k6w26) form a distorted TIM β/α barrel fold capped by a C-terminal helix similar to that of the target structure. Although the target TIM β/α barrel is composed of only seven strands and helices, both structures bind transition metals within the barrel using the conserved metal-binding motif. However, in the absence of stronger evidence, we classified this target as an analog [FR(A)].

Analysis of Difficult Structure Analogs

The remaining CASP5 target domains belonged to one of two categories: structural analogs and new folds. To make sure we did not miss any potential template folds of the target domains and to help make the distinction between structure analogs and new folds, we used a secondary structure vector search program under development in our laboratory. To perform this vector search, the secondary structural elements belonging to each target domain were defined, and a matrix of contacts between these elements that included the types of interactions (i.e., parallel, antiparallel) and the handedness of connections was constructed. We used this target matrix to search for exact matches in a database of similar matrices defined for all available PDB structures. This program finds topological and architectural similarities including circular permutations but is not sensitive to structural details such as packing, length of secondary structure elements, or large insertions.

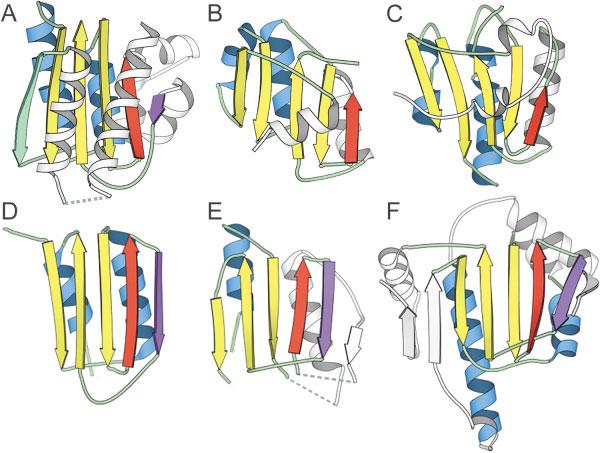

An example of the utility of the vector search is illustrated with the first domain of target T0187, a putative glycerate kinase from T. maritima [Fig. 4(A)]. A Dali search using this domain did not identify any reasonable structure templates in the PDB. However, the vector search program found a hit to cobalt precorrin-4-methyltransferase CbiF domain 2 [1cbf,27 Fig. 4(B)]. Both target and template structures displayed a central mixed sheet of 5 β-strands (order 12534) surrounded by α-helices. However, the target fold included an extra α-helix at the N-terminus and an extra α/β insertion between the last two β-strands that formed the edge of the β-sheet (Fig. 4). It is of interest that one group (Brooks, Group 373) identified this structure (1cbf) as a parent template for the target [Fig. 4(C)]. Although the topological arrangement of the core folds of each of these structures was similar, the packing of the connecting helices around the sheet differed significantly, providing an explanation for the lack of detection by Dali.

Fig. 4.

Identification of distant structure analogs using vector search. A: The experimental model structure of the first domain (T0187_1) of a putative glycerate kinase from T. maritima found B a structural analog cobalt precorrin-4methyltransferase CbiF domain 2 (1cbf) using a vector search program. C: The first model prediction of one group (Brooks, Group 373) is based on this parent template. D: Another CASP5 target domain (T0149_2) was linked to T0187_1 by using a different definition of core secondary structural elements (includes the purple strand). The vector search program identified (E) homoserine dehydrogenase domain 2 (1ebf_B149-337) and (F) heat shock protein HSP90 (1a4h_A1-214) as distant structural analogs of target T0149_2. Secondary structural elements belonging to the core fold are colored according to type: β-sheets are yellow and α-helices are blue. The β-strand colored in purple represents a core element in target T0149_2 and related structures. The β-strand colored green is deleted in target T0149_2 and related structures. Secondary structural elements that are treated as insertions are colored white.

By including circular permutations and allowing for different insertions to the core fold of the target domain (T0187_1), we searched for templates containing even greater structural variability. Using this strategy, we linked the putative glycerate kinase domain (T0187_1) to another CASP 5 target domain [T0149_2, Fig. 4(D)]. This similarity assumed including the edge strand insertion of target T0187_1 as a core secondary structural element [purple, Fig. 4(A)] and treating the first β-strand as an insertion. The resulting common antiparallel sheet resembled those of two existing structures: homoserine dehydrogenase domain 2 (1ebf_B149-337,28 Fig. 4(E)] and heat shock protein HSP90 [1a4h_A1-214,29 Fig. 4(F)].

Fig. 1.

CASP5 domains. Thumbnail images of CASP5 targets, created by using the graphics program RasMol.30 Models of the CASP5 target structures are split into domains, and indicated domains are colored according to secondary structural elements: α-helix (pink) and β-sheet (yellow), with the remaining secondary structural elements colored gray. The number to the lower left of each image indicates the target length, and colored block to the upper left of each image indicates the target classification: CM (red), CM/FR(H) (pink), FR(H) (blue), FR(A) (cyan), FR(A)/NF (green), and NF (black).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We give special thanks to Alexey Murzin for sharing with us his expertise in structural classification. We also recognize the X-ray crystallographers and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopists who submitted the experimental structures used as targets for CASP5, including the following structural genomics efforts: M. tuberculosis structural genomics consortium, Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium, Midwest Center for Structural Genomics, Joint Center for Structural Genomics, Structure-to-Function, and New York Structural Genomics Research Consortium.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schlessman JL, Woo D, Joshua-Tor L, Howard JB, Rees DC. Conformational variability in structures of the nitrogenase iron proteins from Azotobacter vinelandii and Clostridium pasteurianum. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:669–685. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herzberg O, Reddy P, Sutrina S, Saier MH, Jr, Reizer J, Kapadia G. Structure of the histidine-containing phosphocarrier protein HPr from Bacillus subtilis at 2.0-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2499–2503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Akker F. Structural insights into the ligand binding domains of membrane bound guanylyl cyclases and natriuretic peptide receptors. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:923–937. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hickman AB, Namboodiri MA, Klein DC, Dyda F. The structural basis of ordered substrate binding by serotonin N-acetyltransferase: enzyme complex at 1.8 A resolution with a bisubstrate analog. Cell. 1999;97:361–369. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angus-Hill ML, Dutnall RN, Tafrov ST, Sternglanz R, Ramakrishnan V. Crystal structure of the histone acetyltransferase Hpa2: a tetrameric member of the Gcn5-related N-acetyltransferase superfamily. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1311–1325. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murzin AG, Brenner SE, Hubbard T, Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–33402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman HM, Baltistuz T, Bhat TN, Bluhm WF, Bourne FE, Burkhardt K, Feng Z, Gilliand GL, Lype L, Jain S, Fagan P, Maruin J, Padilla D, Ravichandran V, Schneider B, Thanki N, Weissig H, Westbrook JP, Zardecki C. The Protein Data Bank and the challenge of structural genomics. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(Suppl):957–995. doi: 10.1038/80734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holm L, Sander C. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holm L, Park J. DaliLite workbench for protein structure comparison. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:566–567. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng X, Zhang X, Pflugrath JW, Studier FW. The structure of bacteriophage T7 lysozyme, a zinc amidase and an inhibitor of T7 RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4034–4038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinch LN, Wrabl J, Krishna SS, Majumdar I, Sadreyev RI, Qi Y, Pei J, Cheng H, Grishin NV. CASP5 assessment of fold recognition target predictions. Proteins. 2003;(Suppl 6):395–409. doi: 10.1002/prot.10557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong H, Hateboer G, Perrakis A, Bernards R, Sixma TK. Crystal structure of murine/human Ubc9 provides insight into the variability of the ubiquitin-conjugating system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21381–21387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobkovsky E, Moews PC, Liu H, Zhao H, Frere JM, Knox JR. Evolution of an enzyme activity: crystallographic structure at 2-A resolution of cephalosporinase from the ampC gene of Enterobacter cloacae P99 and comparison with a class A penicillinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11257–11261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly JA, Kuzin AP. The refined crystallographic structure of a DD-peptidase penicillin-target enzyme at 1.6 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:223–236. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner UG, Petersen EI, Schwab H, Kratky C. EstB from Burkholderia gladioli: a novel esterase with a beta-lactamase fold reveals steric factors to discriminate between esterolytic and beta-lactam cleaving activity. Protein Sci. 2002;11:467–478. doi: 10.1110/ps.33002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dokholyan NV, Shakhnovich B, Shakhnovich EI. Expanding protein universe and its origin from the biological Big Bang. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14132–14136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202497999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traub LM, Downs MA, Westrich JL, Fremont DH. Crystal structure of the alpha appendage of AP-2 reveals a recruitment platform for clathrin-coat assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8907–8912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu Z, Wang M, Potter D, Miziorko HM, Kim JJ. The structure of a binary complex between a mammalian mevalonate kinase and ATP: insights into the reaction mechanism and human inherited disease. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18134–18142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckler DR, Zhou Y, Stock AM. Evidence of intradomain and interdomain flexibility in an OmpR/PhoB homolog from Thermotoga maritima. Structure (Camb) 2002;10:153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzberg O, Owen CC, Kapadia G, McGuire M, Carrol LJ, Noh SJ, Dunaway-Mariano D. Swiveling-domain mechanism for enzymatic phosphotransfer between remote reaction sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2652–2657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ariyoshi M, Vassylyev DG, Iwasaki H, Nakamura H, Shinagawa H, Morikawa K. Atomic structure of the RuvC resolvase: a holliday junction-specific endonuclease from E. coli. Cell. 1994;78:1063–1072. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aravind L, Makarova KS, Koonin EV. SURVEY AND SUMMARY: holliday junction resolvases and related nucleases: identification of new families, phyletic distribution and evolutionary trajectories. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3417–3432. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.18.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aravind L, Koonin EV. Phosphoesterase domains associated with DNA polymerases of diverse origins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3746–3752. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.16.3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ireton GC, McDermott G, Black ME, Stoddard BL. The structure of Escherichia coli cytosine deaminase. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:687–697. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schubert HL, Wilson KS, Raux E, Woodcock SC, Warren MJ. The X-ray structure of a cobalamin biosynthetic enzyme, cobalt-precorrin-4 methyltransferase. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:585–592. doi: 10.1038/846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeLaBarre B, Thompson PR, Wright GD, Berghuis AM. Crystal structures of homoserine dehydrogenase suggest a novel catalytic mechanism for oxidoreductases. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:238–244. doi: 10.1038/73359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prodromou C, Roe SM, O'Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cell. 1997;90:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sayle RA, Milner-White EJ. RASMOL: biomolecular graphics for all. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:374. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Esnouf RM. An extensively modified version of MolScript that includes greatly enhanced coloring capabilities. J Mol Graph Model. 1997;15:132–134. doi: 10.1016/S1093-3263(97)00021-1. 112–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]