Abstract

Fragile X syndrome is caused by an absence of the protein product of the fragile X mental retardation gene (FMR1). The fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) is an RNA-binding protein that regulates translation of associated mRNAs; however, the mechanism for this regulation remains unknown. Constitutively, phosphorylated FMRP (P-FMRP) is found associated with stalled untranslating polyribosomes, and translation of at least one mRNA is down-regulated when FMRP is phosphorylated. Based on our hypothesis that translational regulation by P-FMRP is accomplished through association with the microRNA (miRNA) pathway, we developed a phospho-specific antibody to P-FMRP and showed that P-FMRP associates with increased amounts of precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNA) compared with total FMRP. Furthermore, P-FMRP does not associate with Dicer or Dicer-containing complexes in coimmunoprecipitation experiments or in an in vitro capture assay using a P-FMRP peptide sequence bound to agarose beads. These data show that Dicer-containing complexes bind FMRP at amino acids 496–503 and that phosphorylation disrupts this association with a consequent increase in association with pre-miRNAs. In sum, we propose that in addition to regulating translation, phosphorylation of FMRP regulates its association with the miRNA pathway by modulating association with Dicer.

Keywords: FMRP, phosphorylation, Dicer, miRNA

INTRODUCTION

Fragile X syndrome is the most common form of inherited mental retardation and is caused by the absence of expression of the fragile X mental retardation protein, FMRP. FMRP is an RNA-binding protein that binds a subset of mRNAs (Terracciano et al. 2005). FMRP is phosphorylated on three serines between its nuclear export sequence and its primary RNA binding domain, the RGG box, and is associated with stalled, untranslating polyribosomes when constitutively phosphorylated (Ceman et al. 2003). These data suggest that phosphorylated FMRP (P-FMRP) is involved in mRNA translational suppression, although the mechanism by which this occurs remains unclear.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short RNA sequences (21–23 nucleotides) that bind and regulate mRNAs through imperfect base-pairing interactions with the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of target transcripts (Lee et al. 1993; Bartel 2004; Perron and Provost 2008). Although originally described as suppressing translation of all target mRNAs (Ambros and Lee 2001; Nottrott et al. 2006), miRNAs have recently been shown to be present on actively translating polyribosomes and to activate translation of some target mRNAs (Maroney et al. 2006; Vasudevan and Steitz 2007; Vasudevan et al. 2007). miRNAs are transcribed in the nucleus by RNA polymerase II and then processed into 80 nucleotide precursor segments by the Drosha/DGCR8 protein complex (Lee et al. 2003; Denli et al. 2004; Gregory et al. 2004; Han et al. 2004). These precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNA) are exported to the cytoplasm by exportin 5 (Yi et al. 2003), where they associate with the pre-miRNA processing complex (Bartel 2004; Jin et al. 2004a) and are processed by Dicer into shorter (21–23 nucleotides) double-stranded segments that can then be inserted into the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC) (Hammond et al. 2001; Bartel 2004).

Dicer and other components of the miRNA pathway associate with the Drosophila ortholog of FMRP (Caudy et al. 2002; Ishizuka et al. 2002). Subsequent studies showed that mammalian FMRP also associated with miRNAs, as well as Argonaute 2 (AGO2) (Jin et al. 2004b), the protein necessary for RNAi pathway cleavage and silencing of mRNAs (Hutvagner and Simard 2008). Recently, the autosomal paralog of FMRP, FXR1, was found to be required for translational activation of the miRNA complex regulating TNFα expression (Vasudevan and Steitz 2007).

In addition to its RGG box, FMRP has two hnRNP K homology (KH) domains (Terracciano et al. 2005). In vitro, recombinant FMRP aids assembly of Dicer-processed miRNAs onto target mRNAs by acting as an acceptor protein through its KH2 domain (Plante et al. 2006). Further, FMRP is required for efficient RNAi in cells using luciferase reporters in gene silencing assays (Plante et al. 2006). Taken together, these data point toward a mechanism whereby FMRP regulates translation of mRNAs through a miRNA-mediated mechanism. The goal of this study was to investigate the relationship between FMRP and the miRNA pathway as a mechanism by which FMRP can regulate translation of its bound mRNAs.

RESULTS AND DISSCUSION

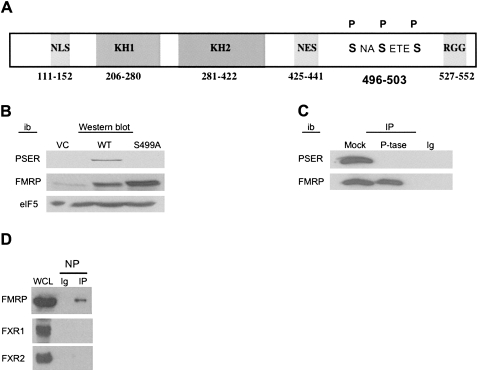

We began this study by creating a phospho-specific antibody to FMRP (PSER) using the 8-amino-acid sequence that includes three serines identified as the sole phosphorylation sites in FMRP: serine (ser) 499 as the primary phosphorylation site and ser496 and ser503 as secondary sites (Fig. 1A; Ceman et al. 2003). To determine whether the PSER antibody was specific to P-FMRP, Western blots were performed on extracts from cells stably expressing FMRP (WT), an empty vector (VC), or an alanine substitution at serine 499 (S499A) variant of FMRP that cannot be phosphorylated (Fig. 1B; Ceman et al. 2003; Narayanan et al. 2007). The PSER antibody did not detect unphosphorylated FMRP in the S499A FMRP cells but did detect P-FMRP in WT cells (Fig. 1B). A longer exposure revealed endogenous P-FMRP in the L-M(TK-) cells (data not shown), which express low levels of FMRP (Ceman et al. 1999). As further evidence that PSER is phospho-specific, phosphatase treatment of immunoprecipitated Flag-FMRP completely eliminated reactivity with the PSER antibody (Fig. 1C). Together, these results indicate that the PSER antibody is specific for P-FMRP. Further evidence for the specificity of this reagent was also described using neuronal preparations (Narayanan et al. 2007). At the same time, we developed an antibody (NP) that detects the same 8-amino-acid region as PSER (SNASETES) but that recognizes FMRP regardless of its phosphorylation state. Although FXR1 and FXR2 contain regions somewhat similar to FMRP, (SNPSETES) and (STASETES), respectively, the NP antibody is specific for FMRP and does not detect FMRP's autosomal paralogs (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

PSER antibody is specific for phosphorylated FMRP. (A) Schematic representation of the FMRP. NLS-nuclear localization sequence, NES-nuclear export sequence, phospho-serines 496, 499, and 503 (adapted from data in Ceman et al. 2003). (B) Western blot of whole-cell lysates from VC, WT, and S499A FMRP expressing cells were immunoblotted (ib) with the indicated antibody: PSER, 1a (anti-FMRP 1a-1C3) (Devys et al. 1993), or eIF5. (C) Anti-Flag immunoprecipitations (IP) of Flag-FMRP expressing L-M[TK-] cells were split and mock-treated or phosphatase (P-tase)-treated (Ceman et al. 2003) before probing with PSER or 1a (anti-FMRP). Ig-immunoprecipitating antibody alone. (D) Flag-FMRP expressing L-M[TK-] cells immunoprecipitated with NP antibody and probed with 1a (anti-FMRP), FXR1, or FXR2 antibodies. WCL-L-M[TK-] whole-cell lysate. Ig-NP indicates antibody alone.

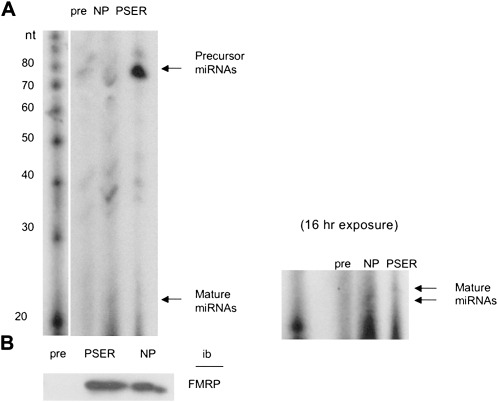

Because P-FMRP has been shown to suppress translation of target mRNAs (Ceman et al. 2003; Narayanan et al. 2007), we hypothesized that the miRNA pathway might play a mechanistic role in the translational regulation of target mRNAs by P-FMRP. To determine if the phosphorylation state of FMRP changes its association with miRNAs, we used the NP antibody, which detects amino acids 496–503, irrespective of the phosphorylation state, and the PSER antibody (Fig. 1) to immunoprecipitate total FMRP and P-FMRP, respectively. Associated RNAs were then extracted and end-labeled with 32P cytidine bisphosphate (Fig. 2A). As shown in Figure 2B, both antibodies capture similar amounts of FMRP. Surprisingly, comparisons between these samples indicated a large amount of 80-nucleotide RNAs associated with P-FMRP (Fig. 2A, top). The size of these RNAs corresponds to the size of precursor miRNAs that have been exported from the nucleus but have not yet been processed by Dicer into mature miRNAs (Jin et al. 2004b).

FIGURE 2.

P-FMRP associates with increased amount of precursor miRNAs. (A) We immunoprecipitated 2 × 109 Flag-FMRP cells with pre-immune serum (pre), NP, or PSER. RNA was extracted and end-labeled with P32 as described (Duan and Jin 2006), resolved on a 15% acrylamide TBE/urea gel, and visualized using autoradiography (8 h). The longer exposure of the gel (16 h, right) shows associated miRNAs. Decade marker system (Ambion) indicates RNA size in nucleotides. (B) Equivalent amounts of FMRP were immunoprecipitated by PSER and NP antibodies in A.

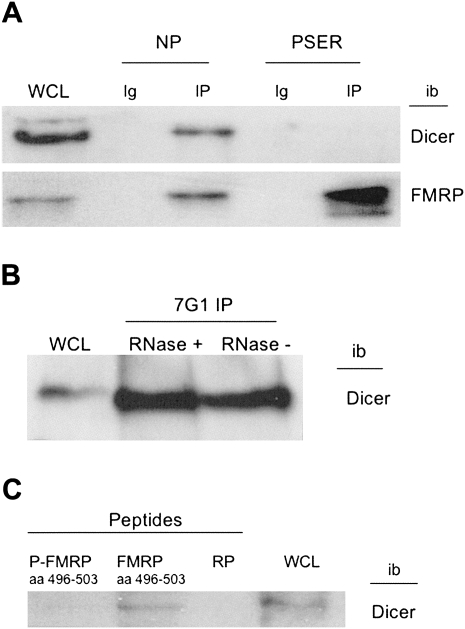

Since P-FMRP associates with large amounts of precursor miRNAs, we hypothesized that Dicer does not associate with P-FMRP and was therefore not present to process precursor miRNAs into mature miRNAs. To test this, we immunoprecipitated total FMRP and P-FMRP from HeLa cells, probed with a Dicer antibody that is specific for human Dicer, and visualized the coimmunoprecipitated proteins by Western analysis. As shown in Figure 3A, Dicer is associated only with total FMRP and not with P-FMRP. To investigate whether the Dicer-FMRP association was mediated by RNA, FMRP was immunoprecipitated from WT cells and then treated with RNase (+) or not (−) and was examined for association with Dicer (Fig. 3B). RNase treatment had no effect on the FMRP–Dicer association, suggesting a protein interaction between Dicer and FMRP.

FIGURE 3.

P-FMRP is unable to associate with Dicer. (A) Lysate from 2 × 107 HeLa cells was immunoprecipitated with NP or PSER antibodies and immunoblotted (ib) with Dicer antibody or FMRP (1a) antibody. (WCL)-50 μg HeLa whole-cell lysate; IP, immunoprecipitations; and Ig, immunoprecipitating antibody alone. (B) Lysate from 109 Flag-FMRP-expressing cells was immunoprecipitated with anti-FMRP antibody 7G1 (Brown et al. 2001), split, and incubated with either RNase (+) or mock-treated (−) and immunoblotted (ib) with the Dicer antibody. (WCL)-50 μg whole-cell lysate. (C) Lysate from 107 HeLa cells was incubated with matrix-coupled peptide (NH2-SNA[pS]ETES-CONH2) (P-FMRP), (NH2-SNASETES-CONH2) (FMRP), or random peptide (RP) (KETAAAKFERQHMDS); resolved on a 6% SDS-PAGE gel; and immunoblotted with Dicer antibody.

To test whether Dicer, or a Dicer-containing complex, directly interacts with FMRP at its phosphorylation site, we compared the ability of Dicer to be captured by beads linked to the 8-amino-acid phospho-peptide sequence of FMRP (SNA[pS]ETES) or the corresponding unphosphorylated FMRP peptide sequence (SNASETES). In Figure 3C, Dicer is only captured by the nonphosphorylated SNASETES peptide and not by the phosphorylated peptide sequence or a random peptide sequence (RP). Thus, Dicer association with FMRP requires unphosphorylated region 496–503. This result also rules out the possibility that PSER binding to FMRP blocks Dicer association.

In summary, we originally set out to test the hypothesis that phosphorylation of FMRP inhibits translation of its mRNA cargoes by preferentially associating with miRNAs. In fact, we found that P-FMRP associates with an increased amount of precursor miRNAs, likely due to its inability to bind Dicer. We then demonstrated that Dicer binds unphosphorylated FMRP on residues 496–503. Thus, we propose a new role for phosphorylation in the regulation of FMRP function where phosphorylation inhibits FMRP association with Dicer, a key enzyme in the generation of miRNAs. As a consequence of reduced association with Dicer, we predict a paucity of miRNAs available for association with the mRNAs bound by P-FMRP. If miRNAs are required for translation activation as recently described (Maroney et al. 2006; Vasudevan and Steitz 2007; Vasudevan et al. 2007), then phosphorylation would suppress translation indirectly by decreasing miRNA production through loss of Dicer binding. Further study is required to investigate whether there is translation activation of mRNAs by miRNAs associated with nonphosphorylated FMRP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and antibodies

Stably transfected L-M(TK-) cells were created and maintained as described (Ceman et al. 2003). Nonadherent HeLa cells were maintained in Joklik + HEPES + 5% NBCS (HyClone). The rabbit anti-phospho-FMRP-specific antibody (phospho-serine or PSER) was raised against the phospho-FMRP peptide NH2-CNSEA(pS)Na(pS)ETE(pS)DHRDE) (Abgent). The rabbit anti-FMRP antibody (NP) was obtained at the same time. Anti-FMRP antibody IAC-1C3, hereafter referred to as monoclonal antibody 1a (Devys et al. 1993), was generously provided by Dr. Jean-Louis Mandel (Université Louis Pasteur de Strasbourg) and was used in immunoblots where indicated. The anti-Flag coupled agarose matrix (Sigma) was used to immunoprecipitate Flag-tagged FMRP in the phospho-specific antibody characterization experiments. Anti-eukaryotic initiation factor 5 (eIF5) (Santa Cruz) was used as a loading control. Mouse anti-Dicer (Abcam) was used to detect the Dicer enzyme in coimmunoprecipitation. Rabbit anti-Dicer (Santa Cruz) was used to detect Dicer in the capture assay. Antibody reactivity was visualized using either an anti-mouse HRP conjugate (Jackson Immunoresearch) or an anti-rabbit HRP conjugate (GE Healthcare) and developed with ECL (GE Healthcare).

P-FMRP and NP antibody characterizations

Whole-cell extracts of L-M(TK-) cells stably expressing WT, S499A, or VC were resolved by 7.5% SDS-PAGE; transferred to Hybond-P PVDF (GE Healthcare); and probed with 1/454 dilution of PSER, 1/10 of 1a hybridoma supernatant, or 1/10,000 of anti-eIF5. We lysed 107 Flag-FMRP expressing L-M(TK-) cells in 1 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 7.6, 300 mM NaCl, 30 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100), and the cells were immunoprecipitated with the anti-Flag antibody for 2 h. After two washes, the immunoprecipitate (IP) was split and either mock-treated or treated with 7.5 μL of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (US Biochemical) for 30 min at 37°C (Ceman et al. 2003). The IPs were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with the PSER, as described above. L-M[TK-] cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated as described above except NP antibody was used, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and then probed with either anti-FMRP (1a), FXR1, or FXR2 as described above.

Precursor miRNA isolation and detection

Flag-FMRP expressing L-M(TK-) cells (2 × 109) were lysed in 40 mL of lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 30 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100), and 500 μL was removed for a parallel immunoprecipitation. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with 40 μg NP (total FMRP), 2 μg PSER (phospho-FMRP) antibodies coupled to protein A Sepharose (PAS) (Roche) or 100 μL pre-immune serum coupled to PAS. Total RNA was extracted by phenol chloroform/ethanol precipitation of the immunoprecipitations. The RNA was end-labeled with P32 cytidine bis-phosphate (Perkin Elmer) and resolved on a 15% TBE/urea gel as described (Duan and Jin 2006). The decade size marker system (Ambion) was labeled with P32-CTP and used to size the resulting RNA. Parallel immunoprecipitations were probed for FMRP (1a).

Dicer immunoprecipitation

HeLa cells (2 × 107) were lysed in lysis buffer (see above), and 50 μg of protein was removed for a whole-cell lysate. The extract was then split and immunoprecipitated with either an NP antibody (total FMRP) or PSER (phospho-FMRP) for 2 h, washed, and resolved on a 6% SDS-PAGE gel. After transfer, blots were probed with antibodies for Dicer and FMRP as described above.

RNase treatment

Flag-FMRP expressing cells (109 WT) were lysed (see above) and 50 μg protein was removed for a whole-cell lysate control. The extract was immunoprecipitated with 7G1 FMRP antibody for 2 h. After washing, the extract was split and half treated with RNase (Sigma) for 20 min at 37°C and resolved on a 6% SDS-PAGE gel. Blot was probed with Dicer antibody as described.

Capture assay

HeLa cells (4 × 107) were lysed (see above), and the post-nuclear supernatant was incubated for 2 h at 4°C with 10 μg matrix-coupled nonphosphorylated FMRP peptide sequence (NH2-SNASETES-CONH2) (BioSource), phosphorylated FMRP peptide sequence (NH2-SNA[pS]ETES-CONH2) (BioSource), or a random peptide sequence. After capture, the beads were washed three times for 10 min with one additional 10-min wash in 300 mM NaCl lysis buffer. The protein was resolved on a 6% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to PVDF for probing with the Dicer antibody.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Mary Schuler and Dr. Kannanganattu Prasanth for critical reading of this manuscript, as well as the other members of our laboratory for their helpful comments. We also thank Andre Hoogeveen for the FXR1 antibody and Gideon Dreyfuss for the FXR2 antibody. This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grant HD41591-01 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by the Spastic Paralysis Research Foundation of the Illinois-Eastern Iowa District of Kiwanis International to S.C.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1500809.

REFERENCES

- Ambros V., Lee R. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans . Science. 2001;294:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D. MircroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown V., Jin P., Ceman S., Darnell J.C., O'Donnell W.T., Tenenbaum S.A., Jin X., Feng Y., Wilkinson K.D., Keene J.D., et al. Microarray identification of FMRP-associated brain mRNAs and altered mRNA translational profiles in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 2001;107:477–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudy A., Myers M., Hannon G., Hammond S. Fragile X-related protein and VIG associate with the RNA interference machinery. Genes & Dev. 2002;16:2491–2496. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceman S., Brown V., Warren S.T. Isolation of an FMRP-associated messenger ribonucleoprotein particle and identification of nucleolin and the fragile X-related proteins as components of the complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;12:7925–7932. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.7925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceman S., O'Donnell W., Reed M., Patton S., Pohl J., Warren S. Phosphorylation influences the translation state of FMRP-associated polyribosomes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:3295–3305. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denli A., Tops B., Plasterk R., Ketting R., Hannon G. Processing of primary microRNAs by the microprocessor complex. Nature. 2004;432:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature03049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devys D., Lutz Y., Rouyer N., Bellocq J., Mandel J. The FMR-1 protein is cytoplasmic, most abundant in neurons and appears normal in carriers of fragile X premutation. Nat. Genet. 1993;4:335–340. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan R., Jin P. Identification of messenger RNAs and microRNAs associated with fragile X mental retardation protein. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006;342:267–276. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-123-1:267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory R., Yan K., Amuthan G., Chendrimada T., Doratoaj B., Cooch N., Shiekhattar R. The microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature. 2004;432:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature03120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond S.M., Caudy A.A., Hannon G.J. Post-transcriptional gene silencing by double-stranded RNA. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:110–119. doi: 10.1038/35052556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Lee Y., Yeom K., Kim Y., Jin H., Kim V.N. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes & Dev. 2004;18:3016–3027. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G., Simard M. Argonaute proteins: Key players in RNA silencing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:22–32. doi: 10.1038/nrm2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka A., Siomi M., Siomi H. A Drosophila fragile X protein interacts with components of RNAi and ribosomal proteins. Genes & Dev. 2002;16:2497–2508. doi: 10.1101/gad.1022002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P., Alisch R., Warren S. RNA and microRNAs in fragile X mental retardation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004a;6:1048–1053. doi: 10.1038/ncb1104-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P., Zarnescu D., Ceman S., Nakamoto M., Mowrey J., Jongens T., Nelson D., Moses K., Warren S. Biochemical and genetic interaction between the fragile X mental retardation protein and the microRNA pathway. Nat. Neurosci. 2004b;7:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nn1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R., Feinbaum R., Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complimentarity to lin-14 . Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Ahn C., Choi H., Kim J., Yim J., Lee J., Provost P., Radmark O., Kim S., Kim V.N. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroney P., Yu Y., Fisher J., Nilsen T.W. Evidence that microRNAs are associated with translating messenger RNAs in human cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;12:1102–1107. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan U., Nalavadi V., Nakamoto M., Pallas D., Ceman S., Bassell G., Warren S. FMRP phosphorylation reveals an immediate-early signaling pathway triggered by group I mGluR and mediated by PP2A. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:14349–14357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2969-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottrott S., Simard M., Richter J. Human let-7a miRNA blocks protein production on actively translating polyribosomes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;12:1108–1114. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron P., Provost P. Protein interactions and complexes in human microRNA biogenesis and function. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:2537–2547. doi: 10.2741/2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante I., Davidovic L., Ouellet D., Gobeil L., Tremblay S., Khandjian E., Provost P. Dicer-derived microRNAs are utilized by the fragile X mental retardation protein for assembly on target RNAs. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2006;2006:1–12. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/64347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A., Chiurazzi P., Neri G. Fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Med. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2005;137C:32–37. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan S., Steitz J. AU-Rich-element-mediated upregulation of translation by FXR1 and argonaute 2. Cell. 2007;128:1105–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan S., Tong Y., Steitz J. Switching from repression to activation: MicroRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science. 2007;318:1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1149460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R., Qin Y., Macara I., Cullen B. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes & Dev. 2003;17:3011–3016. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]