Abstract

Background

Literature reporting total daily water intake of community-dwelling older adults is limited. We evaluated differences in total water intake, water sources, water from meal and snack beverages, timing of beverage consumption, and beverage selection for three older age groups (young-old, 65–74 years; middle-old, 75–84 years; and oldest-old, ≥85 years).

Methods

Data for 2,054 older adults from the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey were used for this study. Multivariate analyses controlling for age, sex, race–ethnicity, education, and marital status were conducted to determine differences in water intake variables across the age groups.

Results

Total water intakes found for the middle-old and oldest-old age groups were significantly lower than those found for the young-old age group. The relative contributions of beverages to total water intake were 40.8%, 38.3%, and 36.4% for the young-old, middle-old, and oldest-old, respectively. The water intakes from beverages consumed at snack occasions were significantly lower for the middle-old and oldest-old groups than those for the young-old group. All groups consumed the greatest amount of water in the morning. Coffee was the predominant source of water from beverages for all groups.

Conclusions

This study fills a gap in the literature by providing an analysis of the daily water intake of middle-old and oldest-old adults. We found that the total water intake for the middle-old and oldest-old was significantly lower than that for the young-old. Future research needs to investigate the clinical outcomes associated with declining water intakes of community-dwelling older adults.

Keywords: Fluid intake, Beverage consumption, Aging, Population

RECENTLY, researchers have reported that adults should be obtaining adequate amounts of water if they respond to their thirst signals (1). However, one water recommendation may not be appropriate for all age groups (2). Both insufficient water intake and increased water excretion make aged individuals susceptible to dehydration. Consequently, some researchers contend that promoting adequate fluid intake is the most important modifiable health behavior for ensuring fluid homeostasis in older adults (3).

Age-related changes in behavior and health status predispose all older adults (≥65 years) to dehydration (4,5). Many older adults deliberately avoid drinking beverages because they fear nighttime incontinence (6). In addition, older adults may not recognize that they are thirsty as the sensation of thirst decreases with age, probably due to changes in the activity of osmoreceptors (7). Although it is difficult to examine the effects of aging independently of chronic disease, research suggests that aging is associated with kidney atrophy, decreased cortical blood flow and glomerular filtration rate, and diminished maximal urinary concentrating capacity (8,9). These changes can lead to electrolyte imbalances and enhanced water diuresis (10). Often, dehydration is cited as a reason for emergency room visits and as a secondary diagnosis for hospitalization in the elderly; however, others contend that dehydration may be misdiagnosed in long-term care patients (11–13). Unchecked dehydration can cause changes in body chemistry, kidney failure, kidney stones, urinary tract infections, bowel cancer, and death (14–18).

Despite the consequences of poor hydration, very little attention has been devoted to the measurement of total daily water intake of community-dwelling older adults (19). Studies reported include those with area-specific populations (20), limited sample size (21), or middle-aged participants (≥50 years) included in the analysis (22). Other researchers have examined total water intake in countries other than the United States, particularly Germany and Hungary (3,23, 24). To our knowledge, estimates of total water intake for three older adult age groups, including the oldest-old (≥85 years), from a national U.S. sample have not been reported.

Using a national sample of independent, community-living older adults, we evaluated differences in total water intake for three older age groups (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years). The relative contributions of drinking water, beverages, and food sources to total water intake were determined for these older age groups. Differences in water intakes from beverages at meals versus beverages at snack occasions were also evaluated. Finally, the time of day that the beverages were consumed and the major beverage sources of water for each age group were identified.

METHODS

Data Set

The data source was the U.S. Federal Government’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for 1999–2002, which provides information on American health, demographic, socioeconomic, and food and nutrient consumption characteristics. NHANES 1999–2002 is a complex, multistage probability sample of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population of the United States. Although individuals of all ages were sampled, we selected those respondents who were 65 years or older (N = 2,054) at the time of their interview. Statistical weights were applied to make the sample representative of the U.S. population.

Dietary Assessment

For the 1999–2002 NHANES, individual dietary intakes were collected for 1 day. Although the reliability of total water intake measurements has not been reported, researchers have indicated that food intake data using a 1-day dietary recall are reliable measures of the usual intakes of energy, macronutrients, and several micronutrients of population groups (25). Data were collected with the Automated Multiple-Pass Method, a five-step computer-assisted interview that has been validated with doubly labeled water and investigator-observed food intakes (26–28). Specific probes were used to collect detailed information about each food and beverage item and the amount consumed. Respondents were asked to report the time each food and beverage was eaten and what they would call the eating occasion (e.g., meal vs snack) for that item. Following the 24-hour recall, respondents were asked to estimate their plain drinking water consumption during the previous 24-hour period.

In this analysis, total water intake is defined as the sum of the amount of drinking water consumed and the amount of water consumed from food and beverage sources (NHANES total nutrient intake file). The coding and nutrient calculations of the 24-hour recall were detailed elsewhere (29, 30). Total water intake is presented as grams, grams per kilogram body weight, and grams per 1,000 calories. Total water intakes (g) were compared with the Adequate Intake (AI) recommendations (3,700 g for men and 2,700 g for women) (2).

To determine the contribution of water from food and beverages, the NHANES individual foods file was used. This file contains detailed information about the type and amount of individual foods and beverages reported by each respondent and the amount of water from these foods and beverages. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies 1.0 was used to identify beverages in the individual foods file (the specific USDA food codes are available from the authors). The relative contributions of water (g) from beverages, foods, and plain drinking water were calculated.

The specification of snack and meal occasions was described elsewhere (31). The individual foods file contains the time each beverage was consumed. The relative contribution of beverages to water intake was calculated for four time blocks in a 24-hour period: (i) midnight to 4:59 AM, (ii) 5:00 AM to 12:59 PM, (iii) 1:00 PM to 6:59 PM, and (iv) 7:00 PM to 11:59 PM.

Statistical Software and Analysis

Data manipulation was conducted using SAS software (Version 9.1, 2005; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The NHANES are multistage, stratified area probability samples. To account for sample design and sampling weights, we used STATA (Version 10; College Station, TX) to estimate descriptive and inferential statistics (32).

Linear regression models controlling for gender, race–ethnicity, education, and marital status were used to examine the association between age and total water intake and between age and water intake from beverages consumed at meal and snack occasions.

Age groups are defined as young-old (65–74 years), middle-old (75–84 years), and oldest-old (≥85 years). Race–ethnicity information included Mexican Americans, other Hispanics, non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and other race. Because of the small sample sizes, Mexican Americans and other Hispanics were combined to form Hispanics, and the other race was combined with non-Hispanic Whites. The level of education was defined as less than a high school degree or greater than or equal to a high school degree. The married group also included those who reported living with their partner. The single group included those who were widowed, separated, or never married.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population. The total water intake for both the middle-old (p < .001, p = .019, and p = .027 for g, g/kg, or g/1,000 kcal, respectively) and the oldest-old (p < .001, p = .040, and p = .032 for g, g/kg, or g/1,000 kcal, respectively) was significantly lower than that for the young-old (Table 2). When compared with the AI, we found that 37%, 27%, and 19% of the young-old, middle-old, and oldest-old, respectively, met or exceeded their AI.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Respondents (Aged ≥65 Years) in 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey*

| Age Group in y (%) |

||||

| Characteristic | Young-Old (65 to <75), n = 1,105 | Middle-Old (75 to <85), n = 746 | Oldest-Old (≥85), n = 203 | Total, N = 2,054 |

| Male | 46 | 41 | 33 | 44 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than a high school | 30 | 34 | 44 | 32 |

| Greater than or equal to a high school | 70 | 66 | 56 | 68 |

| Race–ethnicity† | ||||

| Hispanic | 9 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 84 | 88 | 88 | 86 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Marital status‡ | ||||

| Married | 68 | 52 | 29 | 60 |

| Single | 32 | 48 | 71 | 40 |

Notes: Includes participants with complete data for age, sex, ethnicity–race, education, and marital status. Percentages should be totaled within columns. Within characteristics, columns may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Mexican Americans and other Hispanics were combined to for the Hispanic category, and the other race (including multiracial) category was combined with non-Hispanic Whites.

Married includes participants living with their partner. Single included those who were widowed, separated, or never married.

Table 2.

Adjusted Daily Total Water Intake for Each of the Older Age Groups (Aged ≥65 Years): 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey*

| Age Group in y mean (SE) |

|||

| Young-Old (65 to <75), n = 1,105 | Middle-Old (75 to <85), n = 746 | Oldest-Old (≥85), n = 203 | |

| Water intake | |||

| Total (g) | 2,905.8 (39.5) | 2,573.4 (44.1)† | 2,275.8 (69.7)† |

| Total/body weight (g/kg) | 38.4 (0.6) | 36.5 (0.6)† | 35.7 (1.7)† |

| Total/energy intake (g/1,000 kcal) | 1,824.9 (40.7) | 1,743.8 (49.7)† | 1,716.8 (99.5)† |

Notes: Multivariate-adjusted average intakes, controlled for age, sex, race–ethnicity, education, and marital status.

Significantly different than group 65 to <75 years old (p < .05).

The relative contributions of beverages to total water intake were 40.8%, 38.3%, and 36.4% for the young-old, middle-old, and oldest-old, respectively. The relative contributions of plain drinking water to total water intake were 38.1%, 39.4%, and 39.5% and the water contributions of foods were 21.1%, 22.2%, and 24.2% for the young-old, middle-old, and oldest-old, respectively. Because we found an age-related decrease in the relative contribution of beverages to total water intake, our subsequent analysis focused on beverages.

Table 3 shows the water intakes from beverages consumed during snack and meal occasions. Water intake from beverages consumed at meal occasions did not differ significantly for the middle-old (p = .172) or the oldest-old (p = .057) compared with the young-old. However, the water intake from beverages consumed at snack occasions was significantly lower for both the middle-old (p < .001) and the oldest-old (p < .001) compared with the young-old.

Table 3.

Adjusted Daily Water Intake From Beverages at Meal and Snack Occasions for Each of the Older Age Groups (Aged ≥65 Years): 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey*

| Age Group in y mean (SE) |

|||

| Young-Old (65 to <75) | Middle-Old (75 to <85) | Oldest-Old (≥85) | |

| Water intake from beverages (g) | |||

| Meal occasions (n = 1,952) | 802.9 (20.7) | 750.7 (24.9) | 696.3 (25.6) |

| Snack occasions (n = 1,686) | 1,220.9 (36.7) | 1,024.5 (33.5)† | 842.5 (38.8)† |

Notes: Multivariate-adjusted average intakes, controlled for age, sex, race–ethnicity, education, and marital status. Includes only participants who reported any consumption during respective eating occasion.

Significantly different than group 65 to <75 years old (p < .05).

Water intakes from beverages consumed during the 24-hour period are presented in Table 4. We found similar consumption patterns in the three age groups. All elderly consumed the greatest amount of water early in the day (5:00 AM to 12:59 PM). Thereafter, water consumption decreased with the time of day: Less water was consumed in the afternoon (1:00 PM to 6:59 PM) and still less in the evening (7:00 PM to 11:59 PM). Little water was consumed by any group between midnight to 4:59 AM.

Table 4.

Water Intake From Beverages During Various Times of the Day for Each of the Older Age Groups (Aged ≥65 Years): 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey*

| Age Group in y (%) |

|||

| Young-Old (65 to <75) | Middle-Old (75 to <85) | Oldest-Old (≥85) | |

| Water intake from beverages | |||

| Early morning (midnight to 4:59 AM) | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Morning (5:00 AM to 12:59 PM) | 57 | 60 | 60 |

| Afternoon to evening (1:00 PM to 6:59 PM) | 29 | 29 | 30 |

| Night (7:00 PM to 11:59 PM) | 13 | 11 | 10 |

Notes: Percentages should be totaled within columns. Within age groups, columns may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

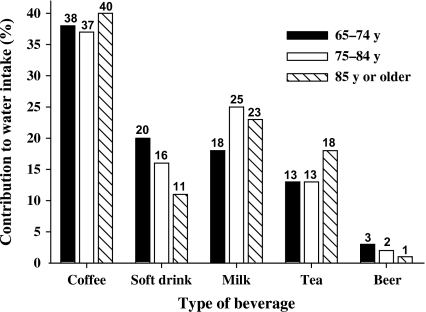

The major beverage contributors to water intakes are presented in Figure 1. Coffee was the predominant beverage source of water for all three groups. Although soft drinks were the second leading source of water for the young-old, milk beverages were the second leading source for the middle-old and oldest-old. The third leading sources of water were the milk beverages group, the soft drinks group, and the tea group for the young-old, the middle-old, and the oldest-old, respectively.

Figure 1.

Top contributors to water intake from beverages for each of the older age groups. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002 and the United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, 1.0.

DISCUSSION

This study fills a gap in the literature by defining the water intakes of a nationally representative sample of middle-old and oldest-old adults. Results from this study indicate that total water intakes appear to decrease with age. This decrease is observed even when considering body weight and caloric intake. Contrary to our results, two smaller area-specific studies found no differences in fluid intake between younger and older adults (21,33). However, neither study included participants in the oldest-old age group. Comparable with our study, but using a representative sample of older German adults, Volkert and colleagues (3) reported that total daily water intake and daily beverage intake decreased with age and found that those 85 years or older had the lowest water intakes. Using hydrogen-labeled water, Raman and colleagues (34) found that water from ingested foods and beverages did not differ significantly among age groups until the eighth decade of life. In a smaller British study, researchers reported that average daily water intakes of community-living older adults (69–88 years) were lower than those found in younger populations (35).

As expected from the total water intakes, the proportion of study participants meeting their AI was the lowest in the oldest-old group. AI is based on the intakes of healthy individuals who appear to be adequately hydrated; however, individuals can be adequately hydrated at lower or higher levels. However, having so few study participants meeting their AI warrants further investigation.

The credibility of the “8 × 8” (eight 8 ounce glasses daily) water recommendation has been questioned (36). No single measure completely discriminates between dehydrated and nondehydrated individuals (5). Lindeman and colleagues (20) suggested that eight glasses of liquid a day may be inappropriate and actually may contribute to incontinence and/or water overload. More recently, Negoianu and Goldfarb (1) questioned the validity of the commonly held belief that adults should drink eight glasses of water per day. Overall, there has been little research to measure the fluid intake of community-dwelling older adults, and fluid intake recommendations for all adults should be evidence based (19). Thus, our aim was to provide a population-level assessment of water intake to assist in the development of evidence-based fluid intake recommendations for older adults.

There were interesting differences between the water contributions of meal and snack beverages. The water intake from beverages consumed as snacks decreased significantly as the age of the population increased. The role of snacking in a healthful diet has been questioned (31). Our results suggest that the consumption of beverages during snack occasions may play an important role in maintaining fluid homeostasis.

There were also differences in the timing of beverage consumption; most beverages were consumed in the morning, whereas few were consumed at night. This finding, and that of De Castro, supports the claim that older adults may deliberately avoid drinking in the evening in order to avoid nighttime incontinence (6,21).

Although there has been a clear societal trend toward soda consumption and away from milk consumption (37), we found that milk beverages were the second leading source of water for the middle-old and oldest-old and that soft drinks were the second leading source of water for the young-old. Some have suggested that these differences may be a cohort effect rather than an effect of aging (21). However, this may be an actual behavior change associated with aging. Jungjohann and colleagues (23) found that elderly men drank significantly fewer soft drinks than the same men did when they were younger. Researchers examining total diet quality have shown that dietary behaviors become more health promoting as individuals age (38).

Coffee and tea consumption were common in our study population. Many health professionals advise individuals to avoid coffee and teas because they contain caffeine and related methylxanthine compounds (39). It is commonly believed that these beverages may trigger dehydration because of their diuretic effects (3). However, Maughan and Griffin (39) found little evidence supporting this hypothesis. The authors noted that little is known about the influence of age and gender on the diuretic effect of caffeine. However, recommendations for older adults to decrease caffeine consumption may be appropriate considering its other stimulant effects and the potential for drug interactions.

One drawback to this analysis is the use of only one 24-hour dietary recall interview. Water intake may vary from day to day. In addition, underreporting issues can be an issue with self-reported data such as a 24-hour dietary recall interview. In a study that examined underreporting issues, the results obtained from 30-year-olds were significantly different than those obtained from older age groups (40-, 50-, and 60-year-olds), but differences were not found when comparisons were made between the older three age groups (40). All our participants were noninstitutionalized; however, there may be the possibility of cognitive impairment in these participants, and this would affect their ability to recall their diet. Another drawback is that we were unable to control for environmental variables (geographical location, seasonality) that could influence water intakes. The AI is for individuals living in temperate climates; thus, we may have misclassified individuals residing in warm climates. With our analysis, we are unable to determine the clinical significance of the observed decrease in water intake. A review of literature in the dietary reference intakes report suggests that increased total water intake may be effective therapy to prevent recurrent kidney stones, gallstones, distal colon tumors, and bladder cancer (41).

An advantage of our study is that we used a nationally representative sample that allows us to generalize to the U.S. population. Another advantage is that we were able to examine adults 85 year or older. Finally, a 24-hour dietary recall allowed us to describe behaviors affecting beverage intake such as timing and beverage selection, which are important considerations when trying to implement behavior change.

Our results suggest that water intakes, particularly the contribution from beverages, appear to decline with age. Future research needs to investigate the clinical outcomes associated with declining water intakes of community-dwelling older adults. Identifying the associations between water intakes and clinical outcomes will also assist in evaluating and determining evidence-based water intake recommendations for older adults.

FUNDING

This study was supported in part by funds from the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station (ALA013-020).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the programming assistance of Yanling Ma, the managerial assistance of Caroline Brawley Johnson, and the graphics assistance of Francis A. Tayie. This manuscript was presented in part at the 2008 Experimental Biology Meeting.

References

- 1.Negoianu D, Goldfarb S. Just add water. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1–3. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otten JJ, Hellwig JP, Meyers LD. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volkert D, Kreuel K, Stehle P. Fluid intake of community-living, independent elderly in Germany—a nationwide, representative study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9:305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rolls BJ. Regulation of food and fluid intake in the elderly. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;561:217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb20984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stookey JD, Pieper CF, Cohen HJ. Is the prevalence of dehydration among community-dwelling older adults really low? Informing current debate over the fluid recommendation for adults aged 70+ years. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8:1275–1285. doi: 10.1079/phn2005829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asplund R, Aberg H. Diurnal-variation in the levels of antidiuretic-hormone in the elderly. J Intern Med. 1991;229:131–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1991.tb00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenney WL, Chiu P. Influence of age on thirst and fluid intake. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1524–1532. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200109000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowe JW, Reubin A, Tobin JD, Norris AH, Shock NW. The effect of age on creatinine clearance in men: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. J Gerontol. 1976;2:155–163. doi: 10.1093/geronj/31.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowe JW, Shock NW, DeFronzo RA. The influence of age on the renal response to water deprivation in man. Nephron. 1976;17:270–278. doi: 10.1159/000180731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayus JC, Arieff AI. Abnormalities of water metabolism in the elderly. Semin Nephrol. 1996;16:277–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders AB, Morley JE. The older person and the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:880–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller J. Disorders of fluid balance. In: Hazzard WR, Blass JP, Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti M, editors. Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003. pp. 581–592. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas DR, Morudian S, Haddad R. Physician misdiagnosis of dehydration in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4:251–254. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000083444.46985.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson MM. The management of dehydration in the nursing home. J Nutr Health Aging. 1999;3:53–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ship JA, Fischer DJ. The relationship between dehydration and parotid salivary gland function in young and older healthy adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M310–M319. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.5.m310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morley JE, Silver AJ. Nutritional issues in nursing-home care. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:850–859. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-11-199512010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morley JE. An overview of diabetes mellitus in older persons. Clin Geriatr Med. 1999;15:211–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleiner SM. Water: an essential but overlooked nutrient. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:200–206. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morley J. Water, water everywhere and not a drop to drink. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M359–M360. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.7.m359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindeman RD, Romero LJ, Liang HC, Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Garry PJ. Do elderly persons need to be encouraged to drink more fluids? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M361–M365. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.7.m361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Castro JM. Age-related-changes in natural spontaneous fluid ingestion and thirst in humans. J Gerontol. 1992;47:P321–P330. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.5.p321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stookey JD. High prevalence of plasma hypertonicity among community-dwelling older adults: results from NHANES III. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:1231–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jungjohann SM, Luhrmann PM, Bender R, Blettner M, Neuhauser-Berthold M. Eight-year trends in food, energy and macronutrient intake in a sample of elderly German subjects. Br J Nutr. 2005;93:361–368. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rurik I. Nutritional differences between elderly men and women. Ann Nutr Metab. 2006;50:45–50. doi: 10.1159/000089564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basiotis PP, Welsh SO, Cronin FJ, Kelsay JL, Mertz W. Number of days of food-intake records required to estimate individual and group nutrient intakes with defined confidence. J Nutr. 1987;117:1638–1641. doi: 10.1093/jn/117.9.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raper N, Perloff B, Ingwersen L, Steinfeldt L, Anand J. An overview of USDAs Dietary Intake Data System. J Food Compost Anal. 2004;17(3–4):545–555. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanton CA, Moshfegh AJ, Baer DJ, Kretsch MJ. The USDA Automated Multiple-Pass Method accurately estimates group total energy and nutrient intake. J Nutr. 2006;136:2594–2599. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rumpler WV, Kramer M, Rhodes DG, Moshfegh AJ, Paul DR. Identifying sources of error using measured food intake. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:544–552. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Center for Health Statistics. 2001–2002 NHANES. Dietary Interview—Total Nutrient Intakes Data File. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_01_02/drxtot_b_doc.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Center for Health Statistics. 1999–2000 NHANES. Dietary Interview—Total Nutrient Intakes Data File. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/frequency/drxtot_cbk.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zizza CA, Tayie FA, Lino M. Benefits of snacking in older Americans. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:800–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Analytic Guidelines. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/analytic_guidelines_dec_2005.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bossingham MJ, Carnell NS, Campbell WW. Water balance, hydration status, and fat-free mass hydration in younger and older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1342–1350. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.6.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raman A, Schoeller DA, Subar AF, et al. Water turnover in 458 American adults 40-79 yr of age. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F394–F401. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00295.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leiper JB, Primrose CS, Primrose WR, Phillimore J, Maughan RJ. A comparison of water turnover in older people in community and institutional settings. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valtin H. “Drink at least eight glasses of water a day.”—Really? Is there scientific evidence for “8 × 8”? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R993–R1004. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00365.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wells HF, Buzby JC. Dietary Assessment of Major Trends in U.S. Food Consumption, 1970–2005. Economic Information Bulletin (EIB-33) Washington, DC: Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/EIB33/EIB33.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basiotis PP, Hirschman JD, Kennedy ET. Economic and sociodemographic determinants of “healthy eating” as measured by USDA's Healthy Eating Index. Consum Interests Annu. 1996;42:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maughan RJ, Griffin J. Caffeine ingestion and fluid balance: a review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2003;16:411–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277x.2003.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johansson G, Wikman A, Ahren AM, Hallmans G, Johansson I. Underreporting of energy intake in repeated 24-hour recalls related to gender, age, weight status, day of interview, educational level, reported food intake, smoking habits and area of living. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:919–927. doi: 10.1079/phn2001124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Panel on Dietary Reference Intakes for Electrolytes and Water: DRI, Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]