Abstract

In this study, the authors evaluated the efficacy of a brief motivational intervention (BMI) and a computerized program for reducing drinking and related problems among college students sanctioned for alcohol violations. Referred students (N = 198, 46% women), stratified by gender, were randomly assigned to a BMI or to the Alcohol 101 Plus computer program. Data obtained at baseline, 1, 6, and 12 months were used to evaluate intervention efficacy. Planned analyses revealed 3 primary findings. First, women who received the BMI reduced drinking more than did women who received the computer intervention; in contrast, men’s drinking reductions did not differ by condition. Second, readiness to change and hazardous drinking status predicted drinking reductions at 1 month postintervention, regardless of intervention. Third, by 1 year, drinking returned to presanction (baseline) levels, with no differences in recidivism between groups. Exploratory analyses revealed an overall mean reduction in drinking immediately after the sanction event and before taking part in an intervention. Furthermore, after the self-initiated reductions prompted by the sanction were accounted for, participation in the BMI but not the computer intervention was found to produce additional reduction in drinking and related consequences.

Keywords: brief intervention, college drinking, alcohol abuse prevention, mandated students, gender

As many as 70% of students in colleges and universities report drinking alcohol in the last month, although most are under the legal drinking age (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002). To comply with minimum legal drinking age legislation and maintain safe living and learning environments, colleges and universities establish policies that restrict alcohol use on campus. U.S. Department of Education data reveal that arrests for liquor law violations on campuses have been increasing for the last 13 years (Hoover, 2005; Porter, 2006). Consistent with the educational mission of these institutions, sanctions for violation of state or campus regulations on alcohol use usually involve some form of alcohol education (Anderson & Gadaleto, 2001). Thus, it is important to evaluate how well required educational programs actually reduce risky drinking.

Limited evidence suggests that mandated interventions for students sanctioned for alcohol violations may reduce alcohol consumption and its consequences (Barnett & Read, 2005). For example, Fromme and Corbin (2004) compared a group alcohol skills class with an assessment-only condition and observed within-groups change on consumption and problems for the group intervention only. Borsari and Carey (2005) compared the efficacy of a single-session brief motivational interview (BMI) with the efficacy of an individual alcohol education intervention at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Although both groups improved over time on consumption, only the BMI group improved on self-reported problems. Comparing an in-person BMI with written feedback only, White et al. (2006) observed improvement on consumption and problems in both conditions at the 3-month follow-up; between-group effects favoring the in-person BMI emerged at 15 months (White, Mun, Pugh, & Morgan, 2007). Barnett and her colleagues (2007) compared a BMI with an interactive CD-ROM program and reported reduced consumption but not problems at 3 months for both conditions. Thus, mandated students benefit from minimal interventions, but research does not provide consistent evidence for differential intervention efficacy.

Prior research raises two questions about the efficacy of mandated interventions. First, how do counselor-administered feedback-based interventions compare with computerized alcohol education interventions? Computer-administered alcohol interventions for use with college students have proliferated, although outcome data remain limited (Elliott, Carey, & Bolles, 2008; Walters, Miller, & Chiauzzi, 2005). One widely distributed intervention is Alcohol 101 Plus (Century Council, 2003), a free CD-ROM provided by the Century Council that provides interactive education and feedback while students navigate through a virtual campus. More than 2,500 colleges and universities have requested copies of Alcohol 101 Plus, according to the Century Council Web site (Century Council, n.d.). Three controlled studies have evaluated the behavioral outcomes of participants who completed the original Alcohol 101. Two studies reported significant within-group improvements at short-term follow-ups after participants completed the Alcohol 101 program (Barnett, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2007; Donohue, Allen, Maurer, Ozols, & DeStefano, 2004), but a third found no change in alcohol use (Sharmer, 2001). No between-groups comparisons favor Alcohol 101; however, the second generation Alcohol 101 Plus has not yet been evaluated.

Thus, research is needed to compare outcomes of computer-administered interventions with those of counselor-administered BMIs when used for indicated prevention. Relative efficacy data would be of practical utility for college administrators. If low-cost computer-administered interventions were found to be equivalently effective, then cost savings could be substantial.

The second question regarding mandated interventions for college drinkers is whether change can be attributed to participation in an intervention or to the experience of being sanctioned for an alcohol policy violation. Interventions with mandated students reveal consistent time effects but inconclusive evidence regarding intervention efficacy. It is likely that receiving a sanction triggers self-initiated change: In one study, women in a wait-list control condition reduced their alcohol consumption from pre- to postassessment (Fromme & Corbin, 2004), whereas 70% of another sample reported reducing their alcohol use immediately after the sanction event and before the mandated intervention took place (Barnett et al., 2004). In recognition of the possibility of postsanction reactivity, the present study defined baseline as the month before the event leading to the sanction. In addition, we obtained limited assessments of drinking behavior after the sanction event but before enrollment in the study (postsanction). This allows exploratory analyses designed to disaggregate the risk reduction effects attributable to the sanction event and those attributable to the interventions.

We had two primary goals for this study. First, we evaluated the efficacy of a counselor-administered BMI versus a computer-administered alcohol education program to reduce alcohol use and related problems among students sanctioned for first-time alcohol violations. We predicted significant short-term improvement attributable to the BMI, consistent with our previous work with voluntary students (Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2006) and other studies using BMIs with mandated students (Borsari & Carey, 2005; White et al., 2006). On the basis of limited research with Alcohol 101, we expected the BMI to be more efficacious than Alcohol 101 Plus at 1 month. We also evaluated outcomes over a 12-month follow-up, a more lengthy follow-up than used in most previous controlled studies with mandated students.

Second, we hypothesized that three person variables (i.e., gender, readiness to change, and level of hazardous drinking) might help to explain variability in response to an intervention. Gender is related to amount of alcohol consumed among young adults (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002) and to responsivity to assessments alone (Fromme & Corbin, 2004). Some studies of BMIs with college students found greater response by women in the sample (Murphy et al., 2004), whereas others did not (Carey, Henson, Carey, & Maisto, 2007; Marlatt et al., 1998). Thus, men and women may differ in their responses to mandated interventions, such that women may be more likely to reduce risky drinking patterns. Readiness to change tends to be low in samples of drinkers mandated to treatment (Kelly, Finney, & Moos, 2005). Interventions with college student volunteers reveal that readiness to change functioned alternatively as a main-effect predictor of change (Carey, Henson, et al., 2007) and a moderator of change (Chiauzzi, Green, Lord, Thum, & Goldstein, 2005; Fromme & Corbin, 2004). Thus, additional research on the role of readiness to change in predicting change in mandated students is warranted. Finally, a recent meta-analysis of college drinking interventions indicated that intervention effects were smaller in the highest risk student groups (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007). Therefore, we assessed hazardous drinking using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993) and hypothesized that students scoring higher on the AUDIT may be less responsive to a single-session intervention than students scoring lower on the AUDIT.

A third, more exploratory goal was to separate the response to the sanction event itself from the response to intervention. We expected that receiving an alcohol-related sanction would produce self-initiated change prior to participation in the study and that the interventions would produce additional risk reduction. In addition, we expected that readiness to change would have a greater effect on self-initiated change than on intervention-triggered change.

Method

Design

In this randomized controlled trial, eligible students were assigned randomly within gender to one of two conditions: (a) an in-person BMI or (b) the Alcohol 101 Plus interactive computer program. All participants provided assessment data at four points: at baseline and at 1-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups. Primary outcome variables included (a) typical drinking (average drinks per week, drinks per typical drinking day), (b) risky drinking (drinks in heaviest week, heavy drinking frequency, peak blood alcohol concentration [BAC]), and (c) drinking-related problems. Secondary outcome variables consisted of repeated contacts with the university judicial system and grade point average (GPA).

Participants

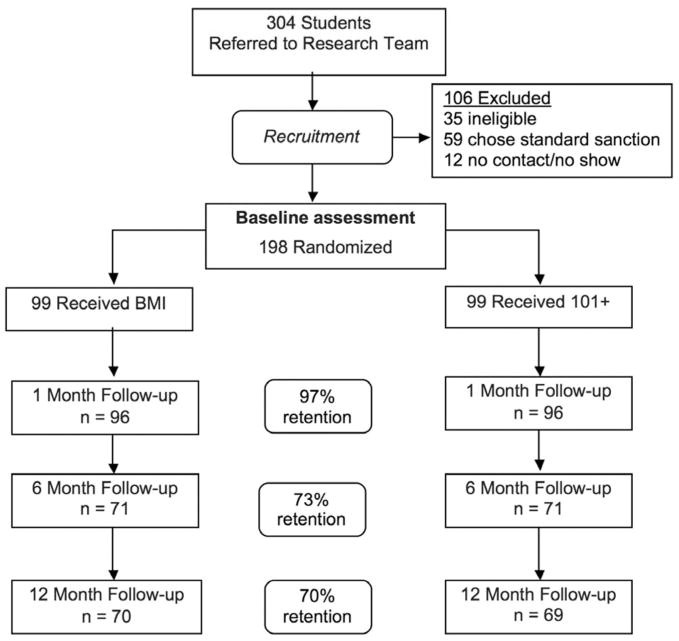

Participants were 198 students enrolled in a private northeastern university who had violated campus alcohol policy and were required to participate in an alcohol education program. Students were eligible if their violation was alcohol related with no drug involvement, it was a first disciplinary sanction, and their violation was not severe enough to warrant referral to Judicial Affairs. Of the 304 students referred to the research team, 35 (11%) were ineligible (because they had participated in a previous study or were referred in the last 3 weeks of a semester, precluding the 1-month follow-up), leaving a pool of 269 to recruit. As summarized in Figure 1, 59 declined research participation and 12 failed to attend any scheduled appointments. Thus, 198 (74% of eligible students) agreed to participate in the study to satisfy their sanction and were randomized (using a random numbers table) to receive either Alcohol 101 Plus (n = 99) or the BMI (n = 99). All nonparticipating students were assigned to the standard sanction.

Figure 1.

Participation flow diagram. BMI = brief motivational intervention; 101+ = Alcohol 101 Plus.

Measures

Descriptive information

Participants provided information regarding gender, age, weight (for BAC calculation), race or ethnicity, residence, and fraternity or sorority affiliation.

Alcohol use

For all assessments, a standard drink was defined as a 10- to 12-oz. can or bottle of 4–5% alcohol content beer, a 4-oz. glass of 12% alcohol content table wine, a 12-oz. bottle or can of 4–6% alcohol content wine cooler, or a 1.25-oz. shot of 80-proof hard liquor either straight or in a mixed drink. Presanction measures covered the month prior to and including the event leading to the sanction; presanction values were treated as baseline values in the analyses. Postsanction measures covered the days since the sanction event until the day of the initial baseline assessment. All follow-up assessments covered the month prior to the day of assessment.

A modified version of the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) used two 7-day grids to assess drinking during a typical week and the heaviest drinking week in the month before the sanction event. Participants also estimated the maximum number of drinks consumed in a single day and the number of hours spent drinking on that day. Peak BAC was estimated from the following formula: [(drinks/2) × (GC/weight)] − (.016 × hours), where (a) drinks = number of standard drinks consumed, (b) hours = number of hours over which the drinks were consumed, (c) weight = weight in pounds, and (d) GC = gender constant (9.0 for women, 7.5 for men; Matthews & Miller, 1979). Participants reported the frequency of heavy drinking in the month before the sanction event, defined as five or more drinks for men and four or more drinks for women on a single occasion (Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, Moeykens, & Rimm, 1995). Participants also reported the number of standard drinks consumed on the day of the sanction.

A limited number of consumption variables were repeated with two separate time frames: for the month prior to the sanction event and also for the variable period since the event that led to the sanction. These included the average number of drinks consumed on a typical drinking day, the number of standard drinks consumed in a typical week, and the maximum number of drinks consumed in 1 day and the hours spent drinking on that day (for estimating peak BAC). This set of consumption variables was chosen to minimize assessment burden and to emphasize measures that would be most meaningful for postsanction intervals that varied from 2–4 weeks on average. These allowed for a determination of distinct and nonoverlapping presanction drinking (the month used as baseline in this study) and postsanction drinking (days between the sanction event and the first study assessment). Finally, participants reported how their drinking since the sanction event compared with their usual drinking (0 = much less, 2 = the same, 4 = much more).

Alcohol problems

The Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) consists of 23 problems resulting from alcohol use. Participants use a 5-point scale (0 = never to 4 = more than 10 times) to indicate how often they experienced any of the problems in the 30 days prior to and including the sanction event. The RAPI coefficient alpha was .84 in this sample.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is a 10-item self-report screener that is a highly sensitive and specific in detecting harmful or hazardous alcohol use in the last year (Allen, Litten, Fertig, & Babor, 1997). It yields scores from 0 – 40 and was internally consistent in the present sample (α = .77). A cutoff (≥10) grouped students into hazardous versus nonhazardous drinkers, consistent with recommendations for older adolescents (Kelly et al., 2004).

Readiness to change

The Readiness-to-Change Questionnaire (RTCQ; Rollnick, Heather, Gold, & Hall, 1992) assessed stage of change with three 4-item subscales: Precontemplation, Contemplation, and Action. Responses were coded on a 5-point Likert-type scale. A continuous score (α = .85) representing readiness to change was derived (Budd & Rollnick, 1996).

Postintervention feedback

A modified Session Evaluation Questionnaire (Stiles & Snow, 1984) consisted of a set of seven items describing the participants’ experience of the session (e.g., difficult–easy; valuable–worthless) on 7-point semantic differentials. Mean scale scores were calculated for the session ratings (α = .84). Participants also provided client satisfaction data on four 5-point scales: Would the student (a) recommend the session to others (1 = definitely no to 5 = definitely yes), and how (b) informative, (c) interesting, and (d) helpful was the session (1 = not at all to 5 = very)? The four client satisfaction ratings were averaged (α = .88).

University records

Participants provided consent for the researchers to request information from university databases to (a) confirm their GPA at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months and (b) determine the existence of additional disciplinary contacts in the 12-month follow-up period.

Recruitment

All recruitment took place during the 2003–2004 and 2004–2005 academic years. Referred students were presented with the options for fulfilling their sanction requirement. Research assistants (RAs) explained study procedures, that participation through the 1-month follow-up would fulfill the sanction, and that students could earn $20 and $25 for participating in the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, respectively. They were told that a certificate of confidentiality protected the confidentiality of their responses. Those who did not choose the research option were assigned to the standard sanction (AlcoholEdu for Sanctions; Outside the Classroom, 2008). Students who consented to participate provided contact information, completed the initial assessment, and received their condition assignment and an intervention appointment within 1 week. Assessment RAs were different staff from those conducting interventions but were not blind to condition.

Interventions

BMI

The BMI has been found to be efficacious when used with heavy-drinking student volunteers (Carey et al., 2006). In brief, it uses personalized feedback and alcohol education to prompt exploration of options for reducing risks related to alcohol use. A personalized feedback sheet structured the BMI session, which covered drinking patterns (with gender-specific national and local norms), estimated typical and peak BAC, and alcohol-related negative consequences and associated risk behaviors (unprotected sex, driving), as well as discussion of harm reduction strategies, individual goal setting, and tips for safer drinking.

The manualized protocol was implemented by three female clinical psychology or counseling graduate students, trained to use a motivational interviewing style (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The sessions were videotaped for supervision and quality assurance. Students had the option of audiotaping or no taping in lieu of videotaping, but none declined videotaping. The BMI sessions lasted an average of 50 min (SD = 13.11), ranging from 25 to 100 min.

Alcohol 101 Plus

This interactive program allows students to explore alcohol-related issues across a virtual campus, engage in social decision making at a virtual party, and learn about factors affecting their own BAC in a virtual bar. Additional alcohol information, including effects on the brain, is available in a game show format. Students navigated through the program at their own pace in a private office in a research suite; they were asked to spend at least 60 min with it, but there was no formal monitoring of content exposure.

After the intervention session, students completed postintervention ratings and returned them in sealed envelopes to preserve the confidentiality of evaluations. Students then received an appointment for the 1-month follow-up.

Intervention Integrity

Interventionist training involved guided reading, study of the BMI manual, practice role-plays with feedback, reviews of videotaped BMIs conducted with confederates, and weekly supervision of videotaped sessions throughout the study. Fidelity to the manual was documented by rating a random set (20%; n = 21) of videotapes, sampling all semesters and interventionists. Manual adherence was evaluated by determining the proportion of the prescribed 54 items present. Maintenance of motivational interviewing style was evaluated by rating 10-min samples of the 21 videotapes for empathy and spirit on 7-point Likert-type scales (1 = low, 7 = high), as defined in the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) code (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, & Miller, 2003). Half (n = 10) of the tapes were rated twice, to determine interrater reliability for adherence both to the manual and to motivational interviewing style.

Follow-Ups

RAs contacted participants (up to 10 times if needed) for follow-up assessments at 1, 6, and 12 months. Most students completed the questionnaires on campus but some completed them by mail (18% at 6 months, 12% at 12 months) if they resided off campus. Completion of the 1-month assessment satisfied their sanction requirement; monetary compensation was offered for completion of the 6- and 12-month assessments.

Data Analytic Plan

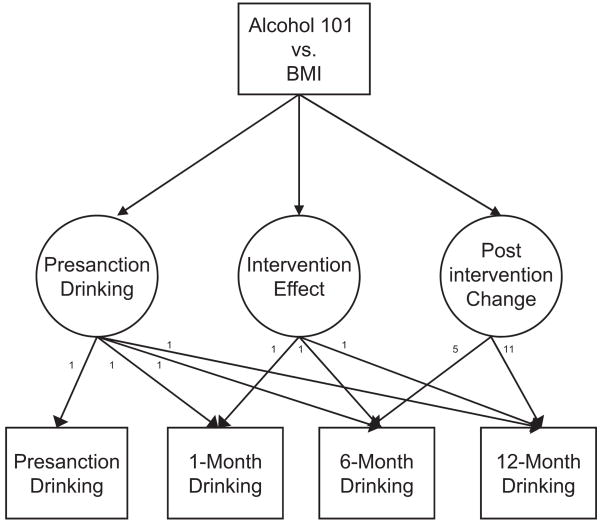

Our primary goals were (a) to compare the efficacy of the mandated BMI and Alcohol 101 Plus interventions and (b) to evaluate the role of person variables in explaining short- and long-term effects. Piecewise latent growth models (PLGMs; see Figure 2) were used to model change in alcohol use from the presanction baseline to the 1-month follow-up (intervention effect) while simultaneously modeling outcomes across follow-ups as a linear function of the 1-, 6-, and 12-month data (postintervention change; Singer & Willett, 2003). PLGMs are an extension of traditional latent growth models, which use a constrained structural equation model (SEM) to fit a typically linear trajectory to the data by constraining factor loadings to represent a specific growth pattern. Whereas traditional SEM models freely estimate most factor loadings, the growth models loadings are fixed to specific values, in this case, to specify the estimation of a presanction value, change from presanction to 1-month postsanction, and change over the last three time points. As Figure 2 illustrates, intervention status is then modeled to predict differences in each of these three aspects of the fitted growth function. Although related to standard within-subject analyses of variance (Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2006), the more flexible PLGM is a more appropriate test of our hypotheses because we do not posit a consistent, linear change over time; rather, consistent with our previous studies (e.g., Carey et al., 2006), we hypothesized an abrupt change immediately after the intervention and then a linear trajectory across follow-up points, and only the PLGM can simultaneously assess these relationships using information from all four time points.

Figure 2.

Piecewise latent growth model, which through proper specification of the factor loadings estimates three distinct components of change: presanction drinking, the change in alcohol use from the presanction baseline to the 1-month follow-up (intervention effect), and the change in alcohol use across the 1-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups (postintervention change). Omitted factor loadings are fixed at 0, and factor scores are interpreted just as with standard regression. The Presanction Drinking factor scores estimate drinking when all other factor loadings are 0. The remaining two factors are interpreted as slopes (i.e., expected change). Therefore, the intervention effect factor scores estimate slopes from 0 (presanction) to 1 (1 month), and the Postintervention Change factor scores estimate slopes from 0 (now 1 month) through the 6-month and 12-month follow-ups. Intervention status is used to predict each of these three aspects of the fitted growth function. BMI = brief motivational intervention; Alcohol 101 = Alcohol 101 Plus.

To address the second goal, potential moderators were then included in the PLGMs as predictors of all three growth factors (presanction drinking, intervention effect, and postintervention change) to identify moderated effects at any stage of the growth process. The hypothesized moderators included gender, readiness to change, and an “at risk” (for alcohol-related problems) indicator operationalized as a score of 10 or higher on the AUDIT. Continuous moderators were grand-mean centered, and categorical moderators were contrast coded (i.e., −.5/.5).

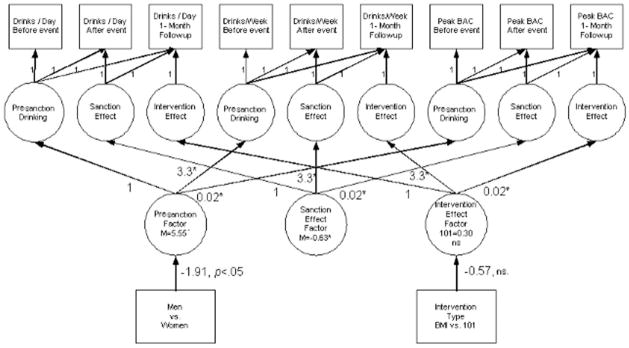

The third, exploratory goal was to disaggregate the effects of the sanction from the effects elicited by the intervention. A piecewise factor-of-curve model (PFOC; see Figure 3) was used to distinguish behavioral changes following the sanction event but before the intervention from behavioral changes after intervention. The PFOC approach to modeling change estimates three distinct PLGMs for the three items (i.e., drinks per typical week, drinks per drinking day, and estimated peak BAC) that summarize drinking behavior prior to sanction, following sanction, and following intervention (see top half of Figure 3). Additionally, the PFOC model combines the three separate piecewise latent growth models into a single, second-order factor, or weighted average, growth model that depicts change based on predictor variables shown on the bottom half of Figure 3 (Duncan et al., 2006). In contrast to the model depicted in Figure 2, these PLGMs assess change from presanction drinking to postsanction and then to postintervention by combining information from all three drinking variables: drinks per typical week, drinks per drinking day, and estimated peak BAC. This approach minimizes idiosyncratic effects from single items by estimating a combined growth function. To assist interpretation of the combined (i.e., second-order) latent growth consumption factors, we arbitrarily fixed their metric to the drinks per drinking day metric, so that the estimated composite growth model results can be interpreted as expected changes in drinks per drinking day. Thus, the PFOC results are not based solely on the drinks per drinking day variable but are expressed as such for ease of interpretability. Furthermore, this model assumes that each variable’s weight (i.e., factor loading) is consistent across the all parts of the estimated second-order growth model (i.e., presanction drinking, sanction effect, and intervention effect) factors and constrains these loadings to equality.

Figure 3.

Piecewise factor-of-curve (PFOC) model, which estimates three distinct piecewise latent growth models for the three items with presanction, postsanction, and postintervention values available (i.e., drinks per drinking day, drinks per typical week, and peak blood alcohol concentration [BAC]; see top half of Figure 3). In the bottom half of Figure 3, the PFOC model combines the three individual piecewise latent growth models into second-order factors (i.e., weighted averages) that depict composite change from (a) presanction drinking during the month prior to the sanction event to (b) postsanction drinking during the weeks following the sanction event and finally to (c) postintervention drinking, assessed at the 1-month follow-up. BMI = brief motivational intervention; 101 = Alcohol 101 Plus.

An important advantage of piecewise latent growth models is that group estimates are robust to missing data under the assumption that data are missing at random. Missing at random implies that the missing data are not systematically contingent on any variable not included in the model. Under this assumption, unbiased estimates can be achieved through EM imputation. Because we found no significant predictors of missingness, missing data were imputed via the EM algorithm as part of the primary analysis using Mplus (Version 4.0).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Sample characteristics

Participants were mostly male (54%), White (91%) underclassmen (freshmen 56%, sophomores 39%), and 78% were not affiliated with any Greek organization. Mean age was 19.17 years (SD = 0.71). Intervention groups did not differ on any of the demographic variables, nor were they different on presanction or postsanction drinking variables (see Table 1). Intervention groups were also equivalent on baseline readiness-to-change scores (overall M = 32.06, SD = 7.44) t(196) = 0.04, p > .05. Baseline assessments took place a median of 18 days after the event leading to the sanction. Most (88%) were completed within a month of the event (range = 4–171 days).

Table 1.

Presanction and Postsanction Alcohol Use Variables by Condition

| Variable | Alc 101 | BMI | Group comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 99 | 99 | |

| Presanction use (month before event) | |||

| AUDIT score | t(196) = 31.28, ns | ||

| M | 9.54 | 10.48 | |

| SD | 4.69 | 5.59 | |

| % below cut score 10 | 53% | 43% | χ2(1, N = 198) = 2.02, ns |

| % at or above cut score 10 | 46% | 57% | |

| Drinks per week: Grid | t(196) =−.08, ns | ||

| M | 14.55 | 14.68 | |

| SD | 10.98 | 10.65 | |

| Drinks per week: Item | t(195) = 0.09, ns | ||

| M | 13.67 | 13.52 | |

| SD | 13.28 | 10.29 | |

| Drinks per drinking day: Grid | t(196) = 0.14, ns | ||

| M | 4.60 | 4.55 | |

| SD | 2.62 | 2.32 | |

| Drinks per drinking day: Item | t(195) = 0.66, ns | ||

| M | 5.73 | 5.42 | |

| SD | 3.83 | 2.64 | |

| Drinks in heaviest week | t(196) = .07, ns | ||

| M | 20.95 | 20.81 | |

| SD | 15.17 | 14.96 | |

| Heavy drinking frequency | t(195) = −0.43, ns | ||

| M | 5.62 | 5.94 | |

| SD | 5.54 | 4.87 | |

| Peak BAC | t(194) = 1.45, ns | ||

| M | .17 | .15 | |

| SD | .09 | .09 | |

| RAPI score | t(196) = 0.03, ns | ||

| M | 4.83 | 4.81 | |

| SD | 4.88 | 4.88 | |

|

| |||

| Postsanction use (between sanction event and intervention) | |||

| Drinks on day of event | t(193) = −0.26, ns | ||

| M | 3.40 | 3.53 | |

| SD | 3.97 | 3.24 | |

| Drank more since the event | 6% | 4% | χ2(2, N = 195) = 1.31, ns |

| Drank same since the event | 45% | 53% | |

| Drank less since the event | 49% | 43% | |

| Drinks per week: Item | t(193) = 0.12, ns | ||

| M | 12.14 | 11.94 | |

| SD | 13.03 | 9.16 | |

| Drinks per drinking day: Item | t(193) = −0.14, ns | ||

| M | 4.92 | 4.98 | |

| SD | 3.84 | 2.49 | |

| Peak BAC | t(194) = 1.07, ns | ||

| M | .14 | .12 | |

| SD | .11 | .08 | |

Note. Single items drinks per week and drinks per drinking day are used to compare pre- and postsanction behaviors. Grid-based assessments are used in longitudinal analyses using (presanction) baseline, 1-, 6-, and 12-month assessments. BMI = brief motivational intervention; Alc 101 = Alcohol 101 Plus; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BAC = blood alcohol concentration; RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index.

The event that led to the sanction was classified according to the Code of Student Conduct, with multiple violations possible per student. The most common violations were illegal purchase, sale, use, or possession of alcohol (76%); misuse of identification cards (18%); conduct threatening the safety of self or others (7%); being in the presence of alcohol in a university residence (4%); disorderly conduct or public intoxication (4%); and failure to comply with a university official (3%).1 Consistent with the relative absence of violations involving disruptive behaviors, alcohol consumption on the day of the sanction event averaged fewer drinks than were typical on a drinking day, t(194) = −4.93, p < .001 (see means in Table 1); most (73%) participants drank less at the sanction event than usual.

Intervention fidelity

On average, interventionists addressed 94% of the 54 prescribed content items (range 85–100%). Across the 54 items, raters agreed on 50% to 100% of judgments (mean Cohen’s κ = 0.93, Mdn = 1.00). MITI ratings confirmed the presence of prescribed style. On 7-point scales, interventionists achieved scores of 6.1 (SD = 0.62) for empathy and 6.1 (SD = 0.70) for motivational interviewing spirit. Reliability for the MITI ratings was calculated using intraclass correlation coefficients; exact agreement was achieved on 60% of the empathy (ρ = 0.63) and 40% of the spirit ratings (ρ = 0.25). Empathy ratings achieved good reliability according to the Cicchetti (1994) guidelines, but the reliability of the spirit ratings was poor.

Client satisfaction

Mean session ratings did not differ by condition (lower scores represent more favorable evaluations): Alcohol 101 Plus M = 1.23 (SD = 0.85), BMI M = 1.28 (SD = 0.95), t(191) = −0.43, p > .05. Thus, the two interventions did not differ in favorability ratings (e.g., comfortable, safe, pleasant, valuable). However, the conditions did differ on the mean satisfaction ratings (higher scores represent more satisfaction), t(188) = −2.77, p < .01 (M = 2.88, SD = 0.89, for Alcohol 101 Plus; M = 3.24, SD = .90, for BMI). Students judged the BMI to be more informative, helpful, and worthy of recommending to others.

Follow-up and attrition

Figure 1 shows that 97% of the 198 students provided data at 1 month, 73% provided data at 6 months, and 70% provided data at 12 months. A total of 87% completed two or more follow-ups, and 68% completed all three follow-ups. Students with missing data did not differ from those who provided complete data with respect to intervention type, gender, class status, GPA, or Greek status, all ps > .05. A stepwise discriminant function analysis revealed no discrimination (prediction) between completers and attriters for any of the presanction drinking variables measured at the baseline assessment, all ps > .05. Furthermore, students who completed follow-ups in person or by mail did not differ on any of the outcome variables, all ps > .05.

Analyses to Determine Intervention Efficacy

PLGM results

This PLGM models (a) variation among individuals’ presanction drinking with the Baseline Drinking factor, (b) presanction to 1-month follow-up change with the Intervention Effect factor, and (c) Postintervention Change as the estimated linear trajectory combined over the 1-, 6-, and 12-month assessments. For the primary model illustrated in Figure 2, intervention status was coded 1 (Alcohol 101 Plus) versus 0 (BMI) to yield the estimated growth model for the BMI condition while testing for significant intervention differences. Residual variances for each time point were constrained to equality. Results of the unmoderated outcome analysis can be obtained from Kate B. Carey. In light of the fact that both Baseline and Intervention Effect factors are qualified by gender, a full presentation of the moderated findings follows.

Moderators were first tested individually, and potential moderators that showed significant main effects or interactions with the intervention effect were entered simultaneously in a final model. To examine convergent validity across outcomes, we included potential moderators in the final model if the main effect or interaction term was significant for any outcome variable, and the final model was kept consistent across all outcomes to ascertain the pattern of relationships. Readiness to change and AUDIT status both exhibited main effects on the presanction drinking factor and the intervention effect, presented in Table 2. Gender was the only predictor that exhibited significant moderation for any of the outcomes. The moderator findings are summarized using 95% confidence intervals in Table 3; intervals that do not contain 0 indicate the estimate is significantly different from 0.

Table 2.

Estimates and 95% Confidence Intervals for Main Effect of Predictors on Presanction Drinking and Intervention Effects for All Outcome Variables

| Presanction drinking factor |

Intervention effect factor |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Lower bound | Estimate | Upper bound | Lower bound | Estimate | Upper bound |

| Readiness to changea | ||||||

| Drinks per typical week | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.19 | −0.33 | −0.20 | −0.01 |

| Drinks per drinking day | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.02 |

| Drinks per heaviest week | −0.06 | 0.16 | 0.32 | −0.49 | −0.31 | −0.08 |

| Peak BAC | .000 | .002 | .004 | −.005 | −.003 | −.001 |

| Heavy drinking frequency | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.17 | −0.07 | 0.05 |

| RAPI total score | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.24 | −0.16 | −0.10 | 0.00 |

| AUDIT statusb | ||||||

| Drinks per typical week | 11.32 | 13.41 | 15.63 | −7.20 | −3.71 | −1.03 |

| Drinks per drinking day | 2.46 | 2.88 | 3.47 | −1.13 | −0.48 | 0.26 |

| Drinks per heaviest week | 12.36 | 16.82 | 19.70 | −6.39 | −3.35 | 0.80 |

| Peak BAC | .073 | .090 | .120 | −.046 | −.006 | .015 |

| Heavy drinking frequency | 5.18 | 6.39 | 7.23 | −3.55 | −1.94 | −0.60 |

| RAPI total score | 4.20 | 5.26 | 6.36 | −2.96 | −1.83 | −0.94 |

Note. BAC = blood alcohol concentration; RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Estimates for which 95% confidence intervals do not contain zero represent significant relationships between predictor and outcome at the .05 level. Estimates for Readiness-to-Change on Peak BAC and RAPI are significant, even though one of the boundaries is rounded to zero.

Tabled values are unstandardized regression coefficients relating readiness-to-change (grand-mean centered at 32.06) to drinking outcome.

Tabled values report expected difference in presanction drinking estimates or presanction to 1-month change comparing individuals scoring 10 or higher on the AUDIT with individuals scoring less than 10.

Table 3.

Estimated Presanction (Baseline) Values, Intervention Effect, and Postintervention Change With 95% Confidence Intervals for Six Outcome Variables, by Condition

| Alcohol 101 Plus |

Brief motivational intervention |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Lower bound | Estimate | Upper bound | Lower bound | Estimate | Upper bound |

| Men | ||||||

| Drinks per typical week | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | 14.64 | 17.04 | 18.70 | 11.71 | 15.12 | 17.24 |

| Intervention effectb | −3.73 | −0.96 | 2.54 | −3.11 | −1.25 | 0.93 |

| Postintervention changec | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.48 |

| Drinks per drinking day | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | 4.68 | 5.44 | 6.00 | 4.33 | 4.80 | 5.30 |

| Intervention effectb | −0.93 | −0.27 | 0.37 | −0.62 | −0.16 | 0.26 |

| Postintervention changec | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Drinks per heaviest week | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | 21.24 | 25.01 | 27.77 | 19.13 | 22.00 | 25.31 |

| Intervention effectb | −6.06 | −1.98 | 2.37 | −6.79 | −3.52 | −1.14 |

| Postintervention changec | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.75 |

| Peak blood alcohol concentration | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | .148 | .172 | .194 | .099 | .130 | .153 |

| Intervention effectb | −.039 | −.012 | .017 | −.045 | −.022 | −.004 |

| Postintervention changec | .001 | .002 | .003 | .001 | .002 | .003 |

| Heavy drinking frequency | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | 5.46 | 6.63 | 7.95 | 4.74 | 5.48 | 6.57 |

| Intervention effectb | −2.72 | −0.85 | 1.16 | −1.93 | −1.09 | −0.35 |

| Postintervention changec | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.29 |

| Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI) total score | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | 4.24 | 4.95 | 5.63 | 3.33 | 4.55 | 5.62 |

| Intervention effectb | −1.43 | 0.04 | 1.11 | −1.79 | −0.43 | 0.29 |

| Postintervention changec | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.17 |

|

| ||||||

| Women | ||||||

| Drinks per typical week | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | 10.44 | 12.70 | 14.86 | 8.87 | 12.22 | 14.57 |

| Intervention effectb | −2.79 | −0.76d | 1.51 | −6.74 | −4.76d | −2.36 |

| Postintervention changec | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.48 |

| Drinks per drinking day | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | 3.33 | 3.85 | 4.40 | 3.34 | 3.84 | 4.23 |

| Intervention effectb | −0.35 | 0.20d | 0.74 | −0.96 | −0.48d | −0.01 |

| Postintervention changec | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Drinks per heaviest week | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | 13.51 | 17.54 | 20.42 | 13.65 | 16.96 | 19.72 |

| Intervention effectb | −3.42 | −0.59d | 3.43 | −9.13 | −6.39d | −3.89 |

| Postintervention changec | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.75 |

| Peak blood alcohol concentration | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | .155 | .175 | .188 | .144 | .167 | .188 |

| Intervention effectb | −.038 | −.014d | .004 | −.055 | −.039d | −.018 |

| Postintervention changec | .001 | .002 | .003 | .001 | .002 | .003 |

| Heavy drinking frequency | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | 3.66 | 4.87 | 5.80 | 3.91 | 5.58 | 6.65 |

| Intervention effectb | −1.32 | −0.18d | 0.93 | −3.64 | −2.74d | −1.62 |

| Postintervention changec | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.29 |

| Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI) total score | ||||||

| Presanction drinkinga | 4.00 | 5.08 | 6.40 | 3.25 | 4.37 | 5.56 |

| Intervention effectb | −2.17 | −0.89 | −0.23 | −2.55 | −1.73 | −1.02 |

| Postintervention changec | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.17 |

Note. Estimates are significantly different from zero if the 95% confidence interval does not contain zero.

Average presanction values per group, holding readiness-to-change and AUDIT status constant.

Expected change in drinking from presanction month to 1-month postintervention follow-up.

Expected monthly drinking change from 1 month to 12 months.

A significant difference exists at the .05 level between the Alcohol 101 and BMI groups.

Main effects of readiness to change and AUDIT

Individuals with higher readiness-to-change scores at the initial baseline assessment tended to have higher estimated peak BACs and RAPI scores, and individuals with scores greater than 10 on the AUDIT at the initial baseline assessment drank significantly more during the presanction month across all outcomes (see Table 2). With regard to the intervention effect, greater readiness to change was associated with greater reductions from presanction to 1 month for all outcomes except heavy drinking frequency. Finally, AUDIT status was related to intervention change for three outcomes (i.e., typical drinks per week, heavy drinking frequency, and RAPI); individuals exceeding the cut score of 10 on the AUDIT decreased more from presanction to 1 month.

Moderated presanction drinking factor

In Table 3, average drinking behaviors are listed by condition separately for each gender and represent expected scores on the outcome measure, controlling for readiness to change and AUDIT status. As expected, all presanction values are significantly greater than zero, and women drank significantly less than men did across all outcome variables except estimated peak BAC and RAPI score.

Moderated intervention effect factor

With readiness to change and AUDIT status held constant, the confidence intervals in Table 3 show that men in the BMI condition exhibited significant decreases for the heavy drinking variables: drinks per heaviest drinking week (3.52 fewer drinks), estimated peak BAC (.022 lower), and heavy drinking frequency (1.09 fewer episodes per month). Men in the Alcohol 101 Plus condition did not change significantly on any of the outcomes (i.e., all confidence intervals for the Intervention Effect factor contain 0). However, none of the intervention outcomes were significantly different across the two intervention conditions.

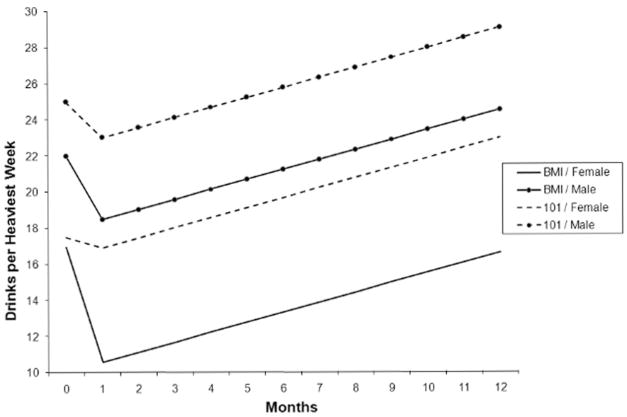

Table 3 reveals a significant intervention effect for women in the BMI condition across all outcomes, such that women in the BMI condition exhibited significant decreases in drinking behaviors for all outcomes (e.g., 4.76 fewer drinks in a typical week). The women in the Alcohol 101 Plus condition exhibited a decrease for RAPI score only. Women in the BMI condition differed from those in the Alcohol 101 Plus condition across all outcomes except RAPI total score. Figure 4 illustrates the modeled changes in drinks in the heaviest week in the last month by gender and condition.

Figure 4.

Expected values for drinks in the heaviest week of the last month, by gender and condition, showing change from presanction, labeled Month 0, to 1 month, labeled Month 1 (i.e., the combined response to sanction and intervention); and slopes across 1-month, 6-month, and 12-month follow-ups. BMI = brief motivational intervention; Alch101 = Alcohol 101 Plus.

Postintervention change factor

None of the predictors helped to explain postintervention growth, and both genders in both groups exhibited significant increases in drinking outcomes from the 1- to the 12-month follow-up. Therefore, in the absence of significant predictors, none were included in the final model to increase model parsimony; as a result, the postintervention growth estimates are identical across all groups.

Exploratory analyses revealed that for most of the outcome variables, 12-month values did not differ from initial presanction values (ps > .05), demonstrating that the increase in drinking exhibited by individuals in the BMI condition reflects a return to presanction behaviors from the reduced drinking observed at 1 month. Only heavy drinking frequency exhibited a main effect of time from presanction to 12 months, F(1, 133) = 5.79, p < .05, with frequency per month increasing from M = 5.66 (SD = 4.94) to M = 6.72 (SD = 5.73) for the whole sample, with no main effects or interactions involving condition or gender.

Secondary outcomes

GPA was obtained from university records concurrent with the baseline, 6-month, and 12-month assessments. At each time point, a 2 (condition) × 2 (gender) analysis of variance revealed no effects for condition but main effects for gender at 6 months: GPAs for female students averaged 3.22 and for male students averaged 3.06, F(1, 158) = 4.89, p < .05. Fifteen percent of the sample had at least one additional disciplinary contact with Judicial Affairs in the follow-up year, according to official university records.2 Chi-squares revealed no associations between recidivism and condition, gender, or their interaction (all ps >.05).

Exploratory Analyses of Postsanction Change

To separate the effect of receiving a sanction from the effect of the intervention, we fit exploratory models using three items (typical number of drinks per week, drinks per drinking day, and estimated peak BAC) corresponding to the month presanction, the period after sanction but prior to intervention, and the month after intervention. A piecewise factor-of-curve model (PFOC) was fit to these variables, using second-order factors to determine the general form of change from presanction to postsanction to postintervention (see Figure 3). The metric of the second-order factors was set to typical drinks per drinking day, and nonsignificant residual variances were fixed at 0 to ensure model identification. Because gender had an effect on alcohol consumption and intervention efficacy, the initial PFOC model included gender as a covariate for all three growth factors: Presanction Drinking, Postsanction Change, and Postintervention Change. Further, intervention type and the Intervention × Gender interaction term were included to predict the third factor, Postintervention Change.

The presanction drinking composite was equivalent to 6.51 drinks per typical drinking day for men and 4.40 for women, which were significantly different, t(196) = −4.43, p < .05. On average, drinking significantly decreased postsanction, Msanction = −0.63, t(196) = −4.17, p = .05, with no additional change in drinking postintervention, Mintervention = −0.01, t(196) = −0.04, p > .05. There were no significant gender effects for the postsanction or postintervention changes.

Because the postsanction assessment intervals varied, we explored correlational relationships with presanction values and conditions and found no significant associations. However, there was a small, significant correlation with postsanction change (r = .195, p = .007). Specifically, shorter postsanction intervals were associated with greater drinking reductions: As length of time between sanction and initial assessment increased, self-initiated drinking reductions were smaller in magnitude relative to presanction drinking.

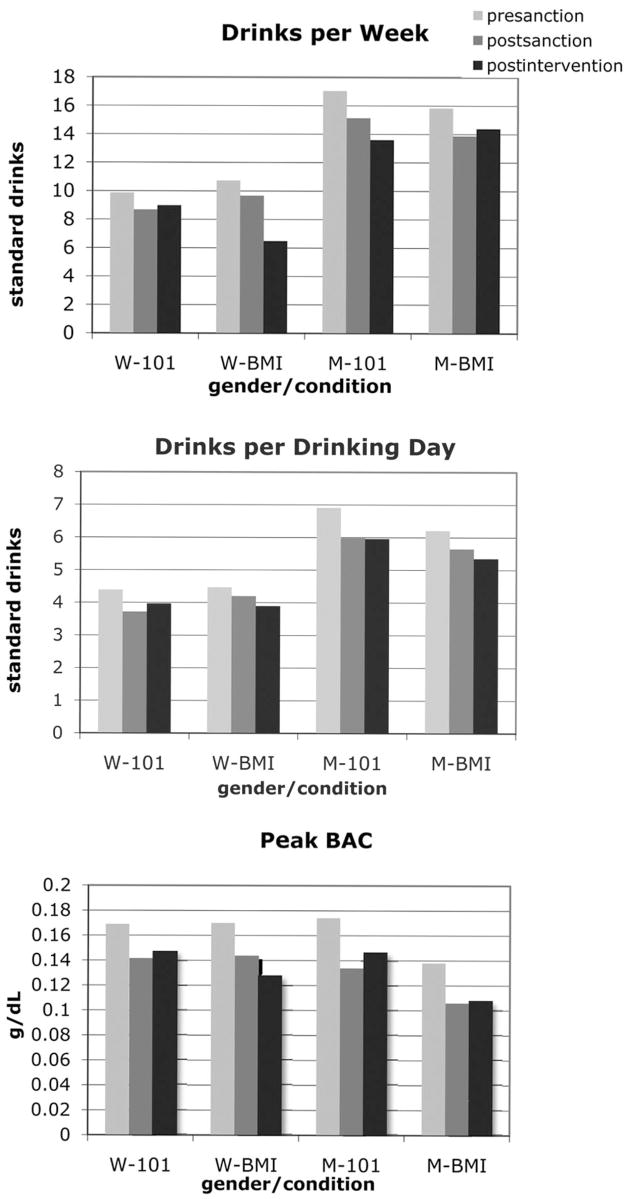

We expected the BMI to yield significantly greater decreases in drinking than Alcohol 101 Plus in composite drinking behaviors from postsanction to postintervention. This test yielded a difference that approached significance (b = −0.59, β = −.16, p = .08), but neither the Alcohol 101 Plus trajectory (b = 0.3, β = .17) nor the BMI trajectory (b = −0.27, β = −.15) was significantly different from 0 from postsanction to postintervention. Thus, neither intervention predicted additional drinking change beyond what was already achieved postsanction. Figure 5 illustrates this pattern, showing raw means from presanction to postsanction to postintervention.

Figure 5.

Raw means for single item outcomes measured at presanction (the month prior to sanction event), postsanction (the weeks between sanction event and first study assessment), and postintervention (the month between intervention and 1-month follow-up), by gender and condition. W = women; 101 = Alcohol 101 Plus; BMI = brief motivational intervention; M = men; BAC = blood alcohol concentration.

To determine if readiness to change or AUDIT status would account for the postsanction change, we included these variables as predictors of the presanction drinking, the postsanction effect, and postintervention effect factors, in addition to gender. With readiness to change and AUDIT status in the model, women drank, on average, 1.52 fewer drinks per drinking day than did men before the sanction event, β =−.25, t(196) = −4.40, p < .05 (using the drinks per drinking day metric). Also, individuals scoring 10 or higher on the AUDIT drank more presanction than did those scoring less than 10, (b = 3.60, β = .59), (t(197) = 10.12, p < .05). Change from presanction to postsanction was predicted only by readiness to change such that higher scores on readiness to change at the initial assessment corresponded to more reported change after the sanction (b = −0.09, β = −.38), t(196) = −4.68, p < .05; neither gender nor AUDIT status predicted the sanction effect. In this model, which controls for variability related to gender, readiness to change, and AUDIT status, intervention status predicted change from postsanction to postintervention. Specifically, individuals in the BMI condition decreased their postintervention drinking more than did those in the Alcohol 101 Plus condition by 0.65 drinks per drinking day, β =−.18, t(196) = −1.97, p < .05. Neither gender nor its interaction with condition predicted postsanction to postintervention change, which suggests that the original significant BMI effect for women was the combination of both sanction-related change and intervention.

Discussion

This study compared two alcohol risk reduction interventions—a widely disseminated and inexpensive interactive computer program and a counselor-administered BMI—for students who violated university alcohol policies. The pattern of change across multiple, related measures of consumption and consequences indicates superior efficacy for the BMI at 1 month. These findings replicate those of other investigators who documented reductions in drinking or consequences in sanctioned students after an in-person BMI (Barnett et al., 2007; Borsari & Carey, 2005; White et al., 2006) and provide evidence of differential efficacy of a BMI over a credible alternative intervention.

It is important to note that moderation analyses revealed subgroup differences in student response to the interventions. The short-term BMI effect appears to be driven largely by the female students’ response to BMIs. Women improved on all outcomes 1 month after receiving a BMI, whereas men’s responses to the BMI were more selective. This finding is open to at least two interpretations. First, because the therapists were all women, it is possible that client–therapist matching on gender accounted for the relatively greater response of women. We cannot rule out this explanation with our data; however, previous research has not found differential effects based on client–therapist gender matching (e.g., Marlatt et al., 1998). A second explanation is that women are more receptive to BMIs than are men (cf. Murphy et al., 2004). This explanation contrasts with the finding that response to BMIs is stronger for male patients in primary care than for female patients (Kaner et al., 2007). Clearly, primary care and college student samples differ on many developmental variables. For example, drinking in college may be more transitional and socially influenced (Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, Wadsworth, & Johnston, 1996); if gender roles support heavier drinking for men and are less prescriptive of drinking for women (cf. Borsari & Carey, 2006), more flexibility may be observed in the drinking patterns of college women after a brief, individually focused intervention.

Furthermore, a differential intervention effect appears when comparing the response of women who received a BMI with the response of those who received Alcohol 101 Plus. Whereas the women students in the BMI condition improved on every outcome, women students in the Alcohol 101 Plus condition reported reductions only on the RAPI problems measure. This suggests that the intervention of choice for sanctioned women is a face-to-face BMI rather than the self-directed course on CD-ROM. In contrast, men did not reduce risk more after a BMI compared with their risk reduction after the computer course. A meta-analysis of individually focused college drinking intervention studies found that more women in a study sample predicted larger intervention effect sizes in the short term (≤3 months; Carey, Scott-Sheldon, et al., 2007). Thus, compared with college women, college men may be less likely to reduce their drinking and consequences after any intervention. Regardless of the explanation for the gender effects we observed, our findings indicate the need to refine interventions to address the needs of college men.

In addition to gender, we expected to find other moderators of intervention outcomes. Instead, readiness to change and AUDIT classification served as main effects, predicting both presanction drinking and short-term change. As expected, students exceeding the AUDIT cut score reported higher levels of drinking and more problems before the sanction event than those under the cut score. They also reduced their number of drinks per week, frequency of heavy drinking, and RAPI scores to a greater degree at 1 month relative to the lower risk students, regardless of intervention condition. Given that these heavier drinking students had more room for improvement, such a main effect on outcomes is not surprising. It is encouraging, however, that AUDIT classification did not interact with condition, suggesting that the interventions are equally effective for hazardous and less hazardous drinkers.

Similarly, students in both conditions who reported higher levels of readiness to change reduced drinking and reported fewer problems at 1 month when compared with students low in readiness to change, consistent with patterns we have observed previously in nonreferred students (Carey, Henson, et al., 2007). We note that readiness to change was measured at the baseline assessment, after postsanction changes had already occurred. Thus, is it possible that change readiness was already reduced, relative to the presanction time period, as a function of self-initiated risk reductions. This highlights the importance of thoughtful timing of readiness-to-change assessments. Furthermore, the predictive role of readiness to change has not been consistent across college alcohol intervention studies. In one study, students low in readiness to change improved more in individual interventions than in control conditions (Carey, Henson, et al., 2007), whereas in another study, higher levels of readiness to change predicted greater reductions in intervention groups (Fromme & Corbin, 2004). Methodological differences may explain some of the inconsistencies. The construct of readiness to change is difficult to operationalize for college drinkers, who most likely interpret change as idiosyncratic modifications in drinking patterns rather than the adoption of abstinence (Carey & Hester, 2005). It is also possible that intervention content or format may determine whether readiness to change serves as a predictor of change or moderates students’ response to behavioral interventions.

Short-term drinking reductions were not maintained over the follow-up year. Recidivism rates did not differ between intervention groups and student drinking gradually increased in both groups, returning to presanction levels by the 12-month assessment. In contrast, a previous study with nonmandated student volunteers revealed maintenance of risk reduction over the 12 months postintervention (Carey et al., 2006). The difference in postintervention trajectories is even more striking in light of the fact that the volunteer sample consisted of heavier drinkers overall, participants having been selected for reporting at least weekly heavy drinking episodes (cf. 19 vs. 14 drinks per week, estimated peak BAC .21 vs. .16, when contrasting our 2006 sample with the present sample). These different trajectories suggest that the mandated students are at greater risk of increasing drinking over time and may require more intensive, frequent, or tailored interventions. In this regard, Barnett et al. (2007) did not find added benefit from a booster session 1 month after an intervention with their mandated sample. However, the timing of their boosters corresponds with significant intervention effects in the present study, suggesting that boosters may have greater value later in year, when intervention effects have started to decay. Future research should attend to the maintenance of drinking reductions in students selected for high-risk behaviors.

In the absence of a no-intervention condition, it is challenging to disentangle the effects of the intervention from the event that triggered referral to the intervention or to their interaction. Our data suggest that self-initiated reductions in drinking followed the sanction event even before students entered the study. Two potential explanations can be offered for this finding. Observed postsanction reductions may be explained by naturally occurring changes in drinking over the course of the semester (cf. DelBoca, Darkes, Greenbaum, & Goldman, 2004) or by specific self-regulatory responses to the sanction event. In support of the latter explanation, Morgan, White, and Mun (2008) found that a serious violation involving medical or judicial interventions triggered more change prior to an intervention than did a less serious residence hall violation. In this study (in which all students were referred for less serious violations), we found that students higher in readiness to change reported greater self-initiated change than did students lower in readiness to change. Thus, it is plausible that alcohol violations and the ensuing sanction process provoke risk reduction, moderated by the nature of the event and motivational variables. For example, in this study and others (e.g., Williams, Horton, Samet, & Saitz, 2007), readiness to change is positively associated with presanction consequences; thus, it may reflect awareness that drinking can be problematic and that some reduction may be justified. Perhaps the sanction event confirmed the already existing readiness to reduce drinking and served as a cue to action (cf. health belief model; Abraham & Sheeran, 2007). In contrast, students low in readiness to change may have construed the sanction event differently and did not respond with self-initiated change. Although we cannot test the following hypothesis in our data, getting caught for a more serious, potentially life-threatening event may trigger risk reduction even in students who were not already contemplating drinking-related change.

Contrary to expectations, later participation in an intervention did not produce substantial improvement over the self-initiated change for men or women. Only when variability due to readiness-to-change and AUDIT classification were accounted for could we discern additional change attributable to the BMI. Thus, participation in a BMI but not in Alcohol 101 Plus maintained and even enhanced self-initiated drinking reductions in some sanctioned students. Our findings suggest several questions for future research: (a) How much change should be attributed to an intervention after a sanction event? (b) How much change is due to a combination of events (sanction plus intervention) or to their interaction? (c) How close in time should an intervention be, relative to the triggering event, to take advantage of a self-initiated change process that appears to fade over time? Taken together with those of Morgan et al. (2008), our findings suggest the need for designs that address additive or interactive effects of the sanction event before an intervention and explore the effects of sanction-triggering events of varying severity.

The findings should be considered in light of the strengths and limitations of our study. The strengths include a sample of at-risk young adult drinkers for whom efficacious interventions are needed and an ample representation of both genders, permitting tests of gender interactions that helped to explain response to the interventions. We report outcomes over a full year postintervention, including both self-report and archival data sources. In addition, we presented exploratory analyses revealing a temporal sequence confirming both self-initiated and intervention-induced risk reduction.

We note several limitations of the study. First, our design did not include a no-treatment control condition, consistent with most published studies of mandated student interventions (Barnett et al., 2007; Borsari & Carey, 2005; White et al., 2006). Such designs acknowledge the responsibility of college and university administrators to provide remediation to students who violate campus policies. However, relative to designs with no-treatment controls, those that compare interventions with other active interventions tend to produce smaller between-groups effect sizes. A second limitation is the exclusive use of female interventionists. If we had both male and female interventionists, we may have been able to rule out one possibility for the stronger response of female students to the BMI relative to male students. Third, it is possible that the practice of excluding students who were referred during the last 3 weeks of the semester created a temporal bias that might partially explain the sanction effect. This concern is mitigated somewhat when first and second semester data are combined; that is, during the fall semester, drinking levels are highest during the first few weeks, but during the spring semester, rates are highest midsemester (i.e., spring break; DelBoca et al., 2004). Fourth, our RAs were not blind to intervention condition when administering follow-ups. Fifth, our sample lacked diversity on two dimensions (race or ethnicity and severity of the alcohol infraction), which limits generalizability to all referred students. Sixth, to highlight patterns of change across multiple drinking indices, we repeated our primary outcome analyses on all six dependent variables. We acknowledge that these are correlated behaviors and that the tests are nonindependent. However, the overall pattern of results enhances confidence in the validity of the observed outcomes.

In summary, consistent enforcement of alcohol policies at the state and campus levels has been associated with lower heavy drinking rates among students (Knight et al., 2003; Nelson, Naimi, Brewer, & Wechsler, 2005). Our findings confirm that enforcement of rules limiting the use of alcohol on campuses is an intervention for some individuals; referral for an alcohol violation, by itself, seems to have cued self-initiated reduction in drinking among some sanctioned students. Our findings also confirm that a counselor-administered BMI can further reduce alcohol consumption and consequences in selected individuals, even when compared with another active alcohol intervention. Further, these results draw attention to the importance of gender in predicting outcomes after mandated interventions. Although the BMI produced short-term drinking reductions in this sample of sanctioned students, on average, students ended the follow-up year drinking as much as they did before the sanction event. Continued research is needed to identify individual and structural interventions that can provide more sustained risk reduction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01-AA12518 to Kate B. Carey. We thank Carrie Luteran, Stephanie Martino, Andrew McClurg, Dawn Sugarman, and Andrea Weber for their invaluable assistance with this project.

Footnotes

Among the students who did not consent to participate in the study, violations of the Code of Student Conduct were illegal purchase, sale, use, or possession of alcohol (87%); conduct threatening safety of self or others (4%); being in presence of alcohol in a university residence (2%); disorderly conduct or public intoxication (2%); failure to comply with a university official (3%); and misuse of identification cards (1%).

Recidivism rates for students not enrolled in the trial were not available for comparison.

Contributor Information

Kate B. Carey, Center for Health and Behavior, Syracuse University

Michael P. Carey, Center for Health and Behavior, Syracuse University

Stephen A. Maisto, Center for Health and Behavior, Syracuse University

James M. Henson, Department of Psychology, Old Dominion University

References

- Abraham C, Sheeran P. The health belief model. In: Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting health behavior. 2. New York: Open University Press; 2007. pp. 28–80. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, Babor T. A review of research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DS, Gadaleto AF. Results of the 2000 College Alcohol Survey: Comparison with 1997 results and baseline year. Fair-fax, VA: George Mason University, Center for the Advancement of Public Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy and mediation of counselor vs. computer-delivered interventions with mandated college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Read JP. Mandatory alcohol intervention for alcohol-abusing college students: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Tevyaw TO, Fromme K, Borsari B, Carey KB, Corbin W, et al. Brief alcohol interventions with mandated or adjudicated college students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:966–975. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128231.97817.c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Two brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:296–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. How the quality of peer relationships influences college alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25:361–370. doi: 10.1080/09595230600741339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd RJ, Rollnick S. The structure of the Readiness to Change Questionnaire: A test of Prochaska & DiClemente’s transtheoretical model. British Journal of Health Psychology. 1996;1:365–376. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:943–954. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Which heavy drinking college students benefit from a brief motivational intervention? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:663–669. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Hester RK. Rethinking readiness-to-change for at-risk college drinkers. The Addictions Newsletter. 2005;12(2):6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon L, Carey MP, DeMartini K. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Century Council. Alcohol 101 Plus [Computer software] 2003 Retrieved from http://www.alcohol101plus.org/home.html.

- Century Council. (n.d.) Distribution of Alcohol 101 Plus™. Retrieved August 29, 2007, from http://www.alcohol101plus.org/main/distribution.cfm.

- Chiauzzi E, Green TC, Lord S, Thum C, Goldstein M. My student body: A high-risk drinking prevention Web site for college students. Journal of American College Health. 2005;53:263–274. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.6.263-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBoca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: Temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue B, Allen DN, Maurer A, Ozols J, DeStefano G. A controlled evaluation of two prevention programs in reducing alcohol use among college students at low and high risk for alcohol related problems. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2004;48:13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott JC, Carey KB, Bolles JR. Computer-based interventions for college drinking: A qualitative review. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin W. Prevention of heavy drinking and associated negative consequences among mandated and voluntary students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1038–1049. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover E. For the 12th straight year, arrests for alcohol rise on college campuses. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2005 June 24;51:A31. [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EFS, Dickinson HO, Beyer FR, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, Heather N, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations (Art. No. CD004148) [Summary and abstract] 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. Retrieved from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab004148.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kelly JF, Finney JW, Moos R. Substance use disorder patients who are mandated to treatment: Characteristics, treatment process, and 1- and 5-year outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Harris SK, Sherritt L, Kelley K, Van Hook S, Wechsler H. Heavy drinking and alcohol policy enforcement in a statewide public college system. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:696–703. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, et al. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DB, Miller WR. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: Two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addictive Behaviors. 1979;4:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TJ, White HR, Mun EY. Changes in drinking before a mandated brief intervention with college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:286–290. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) code. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Benson TA, Vuchinich RE, Deskins MM, Eakin D, Flood AM, et al. A comparison of personalized feedback for college student drinkers delivered with and without a motivational interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:200–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Wechsler H. The state sets the rate: The relationship among state-specific college binge drinking, state binge drinking rates, and selected state alcohol control policies. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:441–446. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl 14):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outside the Classroom. AlcoholEdu for Sanctions: Overview. 2008 Retrieved October 24, 2008, from http://www.outsidetheclassroom.com/prodandserv/higher/alcoholedu_sanctions/

- Porter JR. Campus arrests for drinking and other offenses jumped sharply in 2004, data show [Daily news article] The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2006 October 18; Available from http://chronicle.com/

- Rollnick S, Heather N, Gold R, Hall W. Development of a short “readiness to change” questionnaire for use in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkers. British Journal of Addictions. 1992;87:743–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption—II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. Getting drunk and growing up: Trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharmer L. Evaluation of alcohol education programs on attitude, knowledge, and self-reported behavior of college students. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2001;24:336–357. doi: 10.1177/01632780122034957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. London: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles WB, Snow JS. Counseling session impact as seen by novice counselors and their clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1984;31:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Miller E, Chiauzzi E. Wired for wellness: E-interventions for addressing college drinking. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Rimm EB. A gender-specific measure of binge drinking among college students. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:982–985. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Morgan TJ, Pugh LA, Celinska K, Labouvie EW, Pandina RJ. Evaluating two brief substance-use interventions for mandated college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:309–317. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Mun EY, Pugh L, Morgan TJ. Long-term effects of brief substance use interventions for mandated college students: Sleeper effects of an in-person personal feedback intervention. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1380–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EC, Horton NJ, Samet JH, Saitz R. Do brief measures of readiness to change predict alcohol consumption and consequences in primary care patients with unhealthy alcohol use? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:428–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]