Abstract

Background

Providing discharge instructions to emergency department (ED) patients is not a standard practice and there is wide disparity in its implementation. There is evidence that ED discharge instructions, especially a pre- formatted one, complements verbal instructions and improves patient communication and management.

Aims

Our aim was to audit the practice of providing a discharge summary in a standardized pre-formatted form to patients visiting the ED at Sundaram Medical Foundation (SMF), Chennai, India.

Methods

Case sheets of 200 patients who visited the ED from 1 July to 31 August 2007 were selected randomly and were assessed for the documentation of the demographic and clinical details in the retained copy of the discharge summary by three medical records personnel independently. Descriptive analysis was used to measure frequency and percentages.

Results

All patients (100%) received a discharge summary and a carbon copy of the same was retained in the hospital. Demographic data, diagnosis, prescription and discharge instructions were written in > 80%. Legibility of the three important sections, namely diagnosis, prescription and discharge instructions, were 66, 76 and 65%, respectively. The diagnosis was written in an abbreviated form in 27%. The patient’s signature was obtained in 80%, while doctors signed in 89%. Investigation results and follow-up advice were not documented in 85 and 93%, respectively.

Conclusion

The pre-formatted discharge summary provided more information than a prescription form in terms of the amount of information written by virtue of its structured nature. Deficiencies did reflect a resistance to change current practices in spite of having a structured data sheet. Physician and staff education could overcome this.

Keywords: Discharge summary, Emergency department, India

Introduction

Effective doctor-patient communication is the cornerstone of good medical care [1–3]. Providing discharge instructions (DI) to in-patients is an accepted routine in hospitals worldwide. However, it is not a standard practice to provide such instructions to patients visiting the emergency department (ED) and there is wide disparity in its implementation [4]. In spite of the fact that the number of patients visiting the ED usually outnumbers in-patients, these patients leave the hospital with varied types of DI. It has been suggested that misinterpretation of these instructions adversely affects patient compliance, appropriate use of medications, treatment, follow-up and outcome [1–3, 5–9]. Also, patient recall of verbal instructions can be poor [10, 11]. There is evidence that ED DI, especially a pre-formatted discharge summary, complements verbal instructions and improves patient communication and management [2, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12]. It also facilitates continuation of patient care in the community after ED visits [9–11].

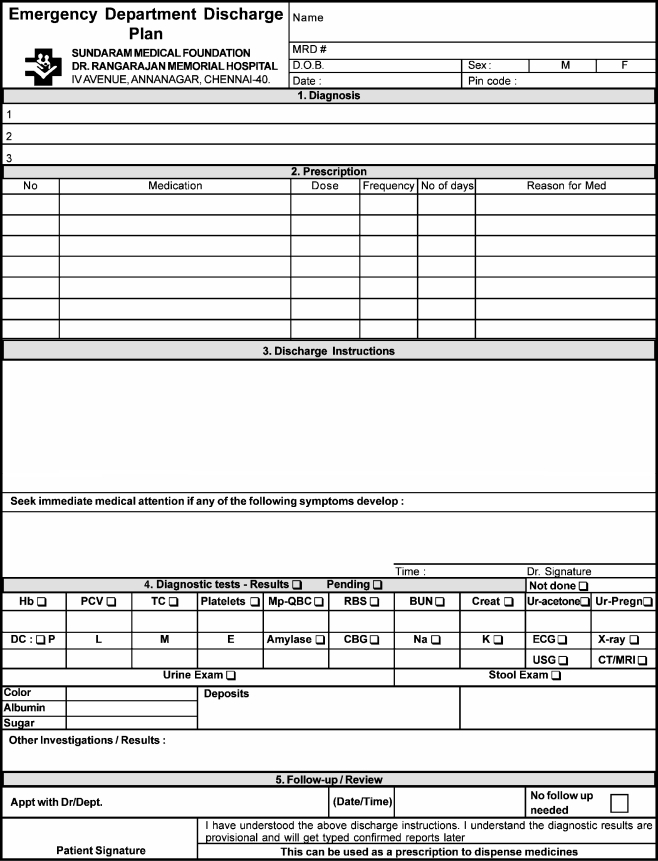

At Sundaram Medical Foundation (SMF) we initiated the practice of providing a discharge summary in a standardized pre-formatted form as shown in Fig. 1. As a part of the audit cycle this new practice was reviewed.

Fig. 1.

Pre-formatted discharge summary

Methods

All patients attending the ED at SMF received a pre-formatted discharge summary. Prior to these, patients were given a plain prescription on a hospital letterhead. The purpose of developing a new form was to standardize this important communication tool. As there is a rapid turnover of junior ED physicians in our hospital, a discharge summary that would provide them with a framework to fill in all the relevant details was necessary. It was also aimed at improving patient compliance, providing a better understanding of the treatment prescribed and as a concise summary for the primary physician. The structured discharge summary was developed after a literature search on this topic [4, 10, 13–15]. Based on this a list of details that had to be included was identified. We wanted to limit the summary to one side of an A4 page, as we wanted to retain a copy of this summary in the case sheet and also if we decided to print this in future it could be done easily. After initial pilot implementation, the feedback of ED staff and consultants was obtained. After incorporating the suggestions, the new discharge summary was substituted for the prescription sheets that had been used earlier. A carbon copy of the discharge summary was retained in the hospital. A total of 200 patients who visited the ED from 1 July to 31 August 2007 were selected randomly and their case sheets were assessed for the documentation of the details in the retained copy of the discharge summary as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Audit of discharge summary

| Details assessed | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Demographic details |

| 2. | Diagnosis |

| 3. | Prescription |

| 4. | Discharge instructions |

| 5. | Investigation values |

| 6. | Follow-up details |

| 7. | Patient’s signature |

| 8. | Doctor’s signature |

The documentation of demographic details consisting of patient name, date of birth, sex, medical record number, date of visit, postal code and clinical details was assessed in terms of completeness and legibility. In addition, presence of the doctor’s signature and patient’s signature acknowledging the comprehension of the explained DI were also assessed. Three medical records department personnel did this assessment independently. Descriptive analysis was used to measure frequency and percentages.

Results

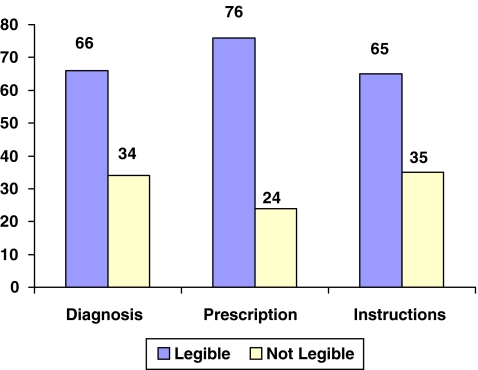

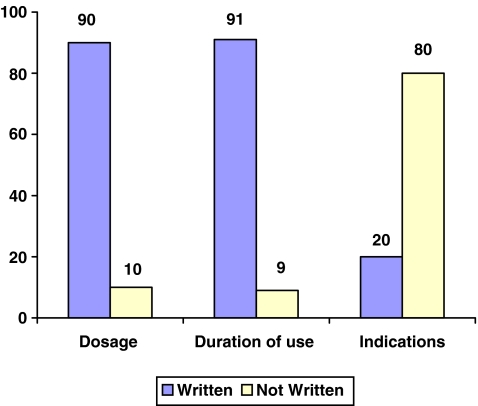

All patients (100%) received a discharge summary and a carbon copy of the same was retained in the hospital. Name of patient, sex, date of visit, diagnosis, prescription and DI were written in more than 80% (Table 2). Legibility of the three important sections, namely diagnosis, prescription and DI, were 66, 76 and 65%, respectively (Fig. 2). In the prescription, dosage and duration were written in more than 90%, but documentation of the indication was very poor at 20% (Fig. 3). The diagnosis was written in an abbreviated form in 27%. The patient’s signature was obtained after explaining the DI in 80%.

Table 2.

Details documented (%), n = 200

| Demographic details | Clinical details | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | 190 (95) | Diagnosis | 176 (88) |

| Medical record no. | 138 (69) | Prescription | 176 (88) |

| Date of birth | 0 (0) | Discharge instructions | 176 (88) |

| Sex | 158 (79) | Investigation values | 30 (15) |

| Date of visit | 168 (84) | Follow-up advice | 14 (7) |

| Postal code | 2 (1) | Doctor’s signature | 178 (89) |

| Patient’s signature | 160 (80) | ||

Fig. 2.

Legibility of documentation (%)

Fig. 3.

Prescription details (%)

Significant deficiencies were found in the documentation of investigation results and follow-up advice. They were not documented in 85 and 93%, respectively. Doctors did not sign the discharge summary in 11%. Date of birth was not entered at all and postal code was entered in two discharge summaries.

Discussion

This audit revealed that all of the patients were given a pre-formatted discharge summary and a copy was retained in the hospital. Information regarding the ED diagnosis, prescription and discharge instructions was given to most patients except for a few deficiencies. Though the legibility was of concern, this could be due to the fact that this assessment was based on the carbon copies rather than the originals given to the patient. The date of birth and postal code were not entered in the discharge summary. Poor documentation of indications for medications and follow-up advice is worrisome as it could either be due to lack of communication or documentation or both. These deficiencies reflect a resistance to change current practices in spite of having a structured data sheet. This could be overcome by physician and staff education. Unless there is a paradigm shift amongst the ED staff, these new practices and tools may not serve the purpose they are intended for.

In spite of this, this pre-formatted discharge summary provided more information than a prescription form just in terms of the amount of information written by its structured nature, which serves as a prompt for the busy ED doctor to fill in all aspects of the summary. It also served as a tool to reinforce the verbal instructions. Obtaining the patient’s signature after explaining the discharge summary was introduced to serve as a motivation for the patient or their representative to understand the DI fully. Further studies are needed to validate this assumption. The retained copy of the summary serves as a valuable document for future reference, to ensure service quality, to standardize treatment practices and for medicolegal purposes.

There are studies that show that when ED information does not accompany patients, it leads to loss in continuity of care [16–18]. Hence a written summary given to the patient at ED discharge could serve as a vital document providing the patient and the family physician with information on management and further follow-up [4]. The information family physicians would like to see in the summary are discharge medications (new or changes), treatment administered, laboratory results, radiology reports, specialty consultations and follow-up plans [13, 14, 19]. Our discharge summary fulfills most of the above criteria. The process of implementing a discharge summary in the ED varies in different parts of the world. A study of DI practices in Australasian EDs found that provision of DI were variable, inconsistent and low overall. It concluded that the rates of provision of DI were inadequate and that there was no standard DI practice [4]. This was also seen in a recent survey of information given to head-injured patients on direct discharge from EDs in Scotland [20]. In view of the above, provision of a standard uniform pre-formatted discharge summary to every patient leaving the ED would be a step forward in ED practices worldwide.

The limitations of this study are that it is an audit and hence retrospective. Further prospective studies are required to compare the effectiveness of a pre-formatted sheet with a prescription sheet. In India, lack of an organized referral system and absence of state health care funding results in patients accessing a doctor based on availability, convenience and financial constraints. As a result, the use of electronic and Information technology in improving communication to patients and the family physicians may be of little benefit here. The simple solution would be to provide a written discharge summary to the patient so that the patient can carry it to any physician for further treatment.

Acknowledgments

Mr. Lakshmanan R, Mr. Wilson Thaya G, Mr. Ilangovan, Mr. Ramkumar S - MRD personnel at Sundaram Medical Foundation for their valuable efforts in this study.

Conflicts of interest None.

Biographies

Nagendra Naidu D V graduated from Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, India. He underwent basic surgical training in surgery at Sundaram Medical Foundation. He is presently a Senior Surgical Registrar and Research Associate in the Emergency Department at Sundaram Medical Foundation (SMF) in Chennai which is a 150-bed, full facility, not-for-profit, postgraduate teaching hospital.

Parivalavan Rajavelu graduated from Madras Medical College, India. He underwent basic surgical training in general surgery in Chennai, India leading to the degrees of MS (general surgery) and DNB (general surgery). He had further training in the UK and obtained FRCS from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, specialising in gastrointestinal and laparoscopic surgery. He is a consultant surgeon and heads the Emergency Department at Sundaram Medical Foundation (SMF) in Chennai which is a 150-bed, full facility, not-for-profit, postgraduate teaching hospital that has a widely acknowledged reputation for an ethos of high-quality, cost-conscious medical care.

Arjun Rajagopalan is the Medical Director & Trustee, Head, Department of Surgery, Sundaram Medical Foundation, Chennai, a 150-bed, full facility, not-for-profit, postgraduate teaching hospital.

References

- 1.Powers RD. Emergency department patient literacy and the readability of patient-directed materials. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:124–126. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(88)80295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spandorfer JM, Karras DJ, Hughes LA, et al. Comprehension of discharge instructions by patients in an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:71–74. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(95)70358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crane JA. Patient comprehension of doctor-patient communication on discharge from the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1997;15:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0736-4679(96)00261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor DM, Cameron PA. Emergency department discharge instructions: a wide variation in practice across Australasia. Emerg Med J. 2000;17:192–195. doi: 10.1136/emj.17.3.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chacon D, Kissoon N, Rich S. Education attainment level of caregivers versus readability level of written instructions in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1994;10:144–149. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerson LW, Counsell SR, Fontanarosa PB, et al. Case finding for cognitive impairment in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:813–817. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayeaux EJ, Jr, Murphy PW, Arnold C, et al. Improving patient education for patients with low literacy skills. Am Fam Physician. 1996;53:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas EJ, Burstin HR, O’Neil AC, et al. Patient noncompliance with medical advice after the emergency department visit. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:49–55. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(96)70296-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vukmir RB, Kremen R, Ellis GL, et al. Compliance with emergency department referral: the effect of computerized discharge instructions. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:819–823. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)80798-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaacman DJ, Purvis K, Gyuro J, et al. Standardized instructions: do they improve communication of discharge information from the emergency department? Pediatrics. 1992;89(6 Pt 2):1204–1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grover G, Berkowitz CD, Lewis RJ. Parental recall after a visit to the emergency department. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1994;33:194–201. doi: 10.1177/000992289403300401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DM, Counselman FL, Caggiano CD. Emergency department discharge instructions and patient literacy: a problem of disparity. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:19–22. doi: 10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van WC, Rokosh E. What is necessary for high-quality discharge summaries? Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:160–169. doi: 10.1177/106286069901400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wass AR, Illingworth RN. What information do general practitioners want about accident and emergency patients? J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13:406–408. doi: 10.1136/emj.13.6.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor DM, Cameron PA. Discharge instructions for emergency department patients: what should we provide? Emerg Med J. 2000;17:86–90. doi: 10.1136/emj.17.2.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stiell A, Forster AJ, Stiell IG, et al. Prevalence of information gaps in the emergency department and the effect on patient outcomes. CMAJ. 2003;169:1023–1028. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunnion ME, Kelly B. From the emergency department to home. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:776–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinker S, Kitai E, Or Y, et al. Primary care follow up of patients discharged from the emergency department: a retrospective study. BMC Fam Pract. 2004;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feied CF, Smith MS, Handler JA, et al. Emergency medicine can play a leadership role in enterprise-wide clinical information systems. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:162–167. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(00)70136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerr J, Swann IJ, Pentland B. A Survey of information given to the head -injured patients on direct discharge from emergency departments in Scotland. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:330–332. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.044230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]