In 2006, after many months of consideration, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recommended that medical schools in the United States increase their enrollment by 30% by 2015 and that residency positions be increased to accommodate the growth in U.S. medical school graduates1. This recommendation is based on the belief that there will be a substantial physician workforce shortage in the future as the economy continues to expand, physicians retire, and patients continue to demand more specialized care. How this prediction will affect the workforce dynamic of orthopaedic surgery and other specialties must be examined carefully.

Orthopaedic surgery, like most specialties, has an interest in better understanding how many physicians will be required in the specialty in the future. This is not to suggest that there is one single correct number of physicians in a specialty; in fact, the medical system has proven to be highly adaptive. However, it is in the public's interest to have a distribution of orthopaedic surgeons that promotes high-quality care. Furthermore, it is in the specialty's interest that the number of physicians be sufficient to provide the services that the specialty is best qualified to perform but not so many that physicians are underutilized. Having too few orthopaedic surgeons can lead to access problems for patients and/or to less qualified providers caring for patients with particular problems. Having too many can increase competition, flatten incomes, and reduce procedural volume for individual surgeons and thereby affect quality and outcomes— not to mention possibly increasing unnecessary operations to maintain income levels. Therefore, it is beneficial to both the public and the orthopaedic surgery specialty to have a supply that is close to expected utilization.

Achieving balance is easier said than done given the many factors that could influence future supply and demand. One must acknowledge that there is a debate based on different assumptions and understandings of medical care. This report briefly reviews the current state of the orthopaedic surgeon workforce and the factors that led the AAMC to conclude that the nation was likely to face a substantial shortage of physicians in the coming decades. The report also points out the potential fallacies of the supply-and-demand model and examines the relationship between studies of practice variation and physician workforce planning. To help leadership determine how best to respond to these workforce shortage predictions, we also examine how increased subspecialization, compensation, and lifestyle factors are impacting the supply of orthopaedic surgeons and may confound current predictions.

Recent Trends in Orthopaedic Surgery Resident and Fellowship Positions

The last American Orthopaedic Association (AOA) symposium on orthopaedic workforce issues was published in this journal in 1998, and it illustrated the difficulty in accurately predicting future workforce needs2. The RAND orthopaedic workforce study, commissioned by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) in December 1995, predicted a 19% surplus of orthopaedic surgeons by 20103. This and other task-and-time projections that attempted to correlate demographic trends with physician supply were inaccurate, projecting surpluses that never materialized. Indeed, despite predicted physician surpluses by health policy planners in the 1990s, the opposite now appears true, as various specialties are now experiencing physician shortages4,5. Educators and planners must now decide how to respond to these most recent predictions and determine whether they require a large-scale institutional response. To begin to address this question, we must first begin with a careful analysis of the current supply of orthopaedic surgeons in the medical school and residency pipeline. Finally, one must acknowledge that there is a debate based on different assumptions and understandings of medical care.

Present ACGME Orthopaedic Surgery Residency Positions

Data from the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) and the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery (ABOS) remained pretty consistent in the last two decades of the twentieth century. Around 610 to 620 orthopaedic residency positions were offered in the match each year, and about that same number of residents graduated and became eligible for board certification. In the past five years, orthopaedic surgery positions comprised between 2.8% and 3.1% of all positions offered in the NRMP6.

Orthopaedic surgery remains a highly sought-after career pathway, with 0.7 orthopaedic residency positions available for each applicant who listed an orthopaedic surgery program as his or her preferred specialty in the rank list7. This makes it one of the more competitive residency positions for students to obtain, as in 2007 only four other specialties (dermatology, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, and radiation oncology) had less than one position offered per applicant7. Of the 719 U.S. senior medical students in the 2007 match who ranked an orthopaedic program as their preferred specialty, 142 did not match in orthopaedic surgery. According to the AAMC8, each applicant applies to approximately forty to forty-six programs a year. Between 2003 and 2007, orthopaedic surgery alternated with dermatology for the residency specialty with the most applications per position. The total number of applicants has risen each year, along with the percentage of female applicants, which increased from 10.9% in 2003 to 11.8% in 2007 (Table I).

TABLE I.

Applicants for Orthopaedic Surgery Residency Positions from 2003 to 2007*

| U.S. Applicants | International Medical Graduate Applicants | Female Applicants (%) | Black Applicants | AOA Members | Asian Applicants | Hispanic Applicants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 927 | 250 | 126 (10.7) | 79 | 213 | 199 | 71 |

| 2004 | 962 | 239 | 131 (10.9) | 77 | 227 | 213 | 73 |

| 2005 | 1002 | 300 | 142 (10.9) | 72 | 218 | 230 | 92 |

| 2006 | 987 | 389 | 153 (11.1) | 96 | 168 | 242 | 82 |

| 2007 | 1048 | 373 | 168 (11.8) | 86 | 215 | 245 | 103 |

Data are from AAMC ERAS web site. http://www.aamc.org/programs/start/statistics/start.htm. Accessed 2007 Aug 20. AOA = American Orthopaedic Association.

Data from the Residency Review Committee of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) suggest that orthopaedic surgery will remain a highly competitive field in the near future. The number of filled residency positions increased between 2002 and 2007 because the total number of ACGME-approved positions also increased by 9.3% over the past five years9 (Tables II and III).

TABLE II.

Filled Residency Positions Reported by ACGME-Accredited Programs in Orthopaedic Surgery*

| Year | PGY-1 | PGY-2 | PGY-3 | PGY-4 | PGY-5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001-2002 | 550 | 617 | 620 | 602 | 592 | 2981 |

| 2002-2003 | 578 | 626 | 626 | 606 | 579 | 3015 |

| 2003-2004 | 611 | 635 | 629 | 616 | 585 | 3076 |

| 2004-2005 | 608 | 650 | 632 | 618 | 608 | 3116 |

| 2005-2006 | 633 | 657 | 637 | 615 | 624 | 3166 |

| 2006-2007 | 653 | 667 | 651 | 621 | 616 | 3208 |

Data from Hart W. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Personal communication, 2007 Feb 24. PGY = postgraduate year.

TABLE III.

Orthopaedic Surgery Residency Positions Approved by ACGME*

| Calendar Year | PGY-1 | PGY-2 | PGY-3 | PGY-4 | PGY-5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001-2002 | 611 | 612 | 614 | 613 | 614 | 3064 |

| 2002-2003 | 617 | 618 | 620 | 619 | 620 | 3094 |

| 2003-2004 | 634 | 635 | 637 | 636 | 637 | 3179 |

| 2004-2005 | 646 | 645 | 646 | 645 | 646 | 3228 |

| 2005-2006 | 657 | 657 | 658 | 657 | 658 | 3287 |

| 2006-2007 | 670 | 670 | 671 | 670 | 671 | 3352 |

Data from Hart W. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Personal communication, 2007 Feb 24. PGY = postgraduate year.

In Tables II and III, several patterns between the number of filled and approved positions are worth noting. First, the number of approved positions has recently been increasing faster than filled positions. From 2001 to 2007, there has been a 7.1% increase in the total number of reported filled positions but only a 4.1% increase in filled positions in postgraduate year (PGY)-5 (Table II). This reflects the fact that it takes five years for an increase in PGY-1 positions to work its way through to the PGY-5 positions.

In Table II, the number of filled positions jumps dramatically between the PGY-1 and PGY-2, at times increasing by 2% to 3%. This occurs for a number of reasons. Many residents complete their PGY-1 year in general surgery, and therefore their positions get reported as general surgery rather than orthopaedic surgery positions. Second, when programs receive an increase in resident complement, they often accept a PGY-1 resident from general surgery for a PGY-2 position in orthopaedic surgery. Any other discrepancy between the number of approved positions and filled positions is probably a manifestation of underreporting by the program director to the ACGME. These data discrepancies are anomalies and should not be considered significant. Given the competitiveness of the specialty over the past twenty years, as exemplified by data from the NRMP, it is unlikely that increasing the number of accredited orthopaedic residency positions will decrease the competitiveness of the field in the near future.

Future Growth of Allopathic Orthopaedic Surgery Positions

The number of accredited orthopaedic residency programs is controlled by the graduate medical education institutions and the Residency Review Committee of the ACGME. Graduate medical institutions must apply to increase or decrease their resident complement. Institutions in general are currently hesitant to ask for more residency positions, as the amount of federal funding for graduate medical education positions has been capped by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. In addition, the Residency Review Committee is explicitly forbidden from considering workforce issues when deliberating over whether to grant a given institution and department approval for an increased number of orthopaedic surgery residents. As clearly delineated by Gebhardt, neither the Residency Review Committee for orthopaedic surgery nor the ABOS is officially involved in any way in determining or controlling the number of practicing orthopaedic surgeons in the United States10. The Residency Review Committee approves or disapproves requests to increase or decrease the resident complement in an individual residency program purely on the strengths and weaknesses of the educational program and the education-to-service ratio, with the explicit purpose to ensure the quality of graduate medical education.

Given these strict stipulations, the recent 9% to 10% increase in approved ACGME-accredited positions in orthopaedic surgery is notable and suggests a change in either the perception of the membership within the orthopaedic surgery Residency Review Committee and/or an increasing willingness of teaching hospitals and orthopaedic surgery departments to expand programs. In addition, it is likely that the duty-hour requirements that the ACGME implemented in 2003 have had an impact on the decision to increase the number of residents. Accordingly, it is reasonable to assume that there may be an additional 5% to 10% increase in ACGME-approved resident positions over the next five years. The increase in PGY-1 positions will lead to an increase in the total number of residents over the next several years. Many of the applications for new positions that are currently in process, as well as those that were originally denied by the ACGME, may be approved in the next three to five years.

Osteopathic Orthopaedic Surgery Residency Positions

When considering the state of the orthopaedic surgeon workforce, it is important to take into consideration the supply of osteopathic orthopaedic surgeons. These surgeons practice in the same communities and provide similar medical and surgical care to that of allopathic orthopaedic surgeons. In fact, many of them take allopathic accredited and unaccredited fellowships and often rotate into allopathic core residency programs. According to the American Osteopathic Academy of Orthopedics (AOAO), there are 992 members with twenty-nine accredited orthopaedic surgery residency programs11. Sixty-four residents are projected to graduate in 2007; seventy-four, in 2008; eighty-four, in 2009; and eighty-two, in 2010. This represents a 31% increase in osteopathic orthopaedic surgeons in addition to the 10% increase to the total supply of allopathic orthopaedic surgeons in the next decade.

It is important to note that the number of ABOS-certified orthopaedic surgeons has not yet increased (Table IV) to reflect the recent 9% increase in ACGME-approved allopathic orthopaedic residencies, nor does it include the number of osteopathic residents in the workforce12. Any assessment of the current and future supply of orthopaedic surgeons must take into account the number of ABOS-certified allopathic orthopaedic surgeons and the recent developments within both the allopathic and osteopathic residency pipelines. In addition, a substantial number of international and American orthopaedic surgeons, including ABOS- eligible surgeons, who are not certified by the ABOS or AOAO are practicing orthopaedic surgery.

TABLE IV.

American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Certification 2002-2006*

| Written Examination

|

Oral Examination

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Examinees | No. Who Passed | No. of Candidates Examined | No. Who Passed | |

| 2002 | 805 | 623 | 707 | 631 |

| 2003 | 760 | 610 | 615 | 563 |

| 2004 | 737 | 614 | 698 | 594 |

| 2005 | 703 | 589 | 697 | 645 |

| 2006 | 741 | 633 | 656 | 593 |

Data from Furr P. American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery. Personal communication, 2007 Mar 29.

Increased Subspecialization

Over the past sixteen years, orthopaedic surgery has become increasingly more and more subspecialized, mirroring trends that are occurring in all fields of medicine. Today, it is estimated that at least 90% of all orthopaedic surgery residents take at least one additional year for accredited or unaccredited fellowships. Recertification examinations from the ABOS were initiated in 1996 and subspecialty-weighted recertification examinations have been available in hand surgery, sports medicine, adult reconstruction, and spine surgery since 1999. However, unlike other specialties such as internal medicine, which not only has accreditation but also has certification in all of its accredited subspecializations, orthopaedic surgery subspecialization is more difficult to track. For example, eight one-year ACGME-accredited fellowships in orthopaedic surgery have been available for almost twenty years, but ABOS certification examinations are only available in sports medicine and hand surgery.

Therefore, in order to get a complete picture of the subspecialization within the field, one must rely on surveys of practicing orthopaedic surgeons. The most recent AAOS survey of practicing orthopaedic surgeons is particularly robust13. The 2006 AAOS survey is valuable for workforce studies because it is more inclusive than past surveys, including candidate and applicant members, practicing emeritus members, and practicing nonmembers. Previous surveys included only full members who were certified by the ABOS and therefore did not give a complete view of the workforce landscape. For instance, women represent only about 3% of full members of the AAOS, but they account for about 6% of all candidate and applicant members. Therefore, while the current survey paints a more accurate picture of the current workforce issues facing orthopaedic surgery, any comparisons to past surveys will be somewhat misleading.

The AAOS survey demonstrates increased fragmentation and subspecialization within the specialty over the last fifteen years. Presently, the most common fellowships that orthopaedic surgeons pursue are sports medicine (25% to 30%), hand surgery (<20%), and adult spine surgery (<15%), followed by adult reconstruction, joint replacement, and pediatric orthopaedic surgery13. Over the past fifteen years, subspecialization has also shifted to sports medicine and spine, with foot and ankle increasing more slowly. Hand, adult reconstruction, and joint replacement have remained stable, while pediatric orthopaedics has decreased in recent years.

Physician and Orthopaedic Surgery Workforce Planning: Dangers and Challenges Ahead from the Perspective of the AAMC

The question that remains is: Will the projected 10% to 15% increase in the number of allopathic and osteopathic orthopaedic surgeons be sufficient to meet the future demands of the U.S. population? Both the AAMC and the Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME) predict substantial physician workforce shortages in the future and are calling for a greater response from medical and graduate programs14.

The Data Behind the AAMC Recommendation

To arrive at this conclusion, the AAMC examined current health-care utilization as well as the active health-care workforce. Baseline estimates of supply considered the current number of practicing physicians and added the annual inflow (residents and/or fellows completing training) while subtracting the estimated annual departures (retirement, deaths, and other). Demand estimates apply current age and gender-specific utilization rates to the expected population in the future. This approach assumes the current system of care will remain unchanged; it does not make a normative statement as to whether the current system is good or bad.

Once the baselines were established, utilization and supply factors were modeled to examine how they might change future balance. For example, the AAMC modeled the impact on supply if the next generation of physicians works more or less hours; if the number of new residents or fellows increases, or decreases, by X% or Y%; if fewer specialty services are required; or if physicians retire earlier or later than in the past. This approach facilitates an understanding of the potential long-term impact of selected changes in the workforce and/or in systems of care.

The AAMC looked at the key factors influencing supply and demand and, under almost all scenarios, found that there will be a substantial physician shortage in coming years.

Key Factors Driving Utilization of Physician Services

1. The growth of the total population. The nation is growing by more than twenty-five million people every decade.

2. The growth of the elderly. There are currently thirty-five million people over the age of sixty-five years in the United States; by 2030, this number will double to over seventy million people. Individuals who are over sixty-five years old use far more physician services than do those under sixty-five years; in fact, on the average, elderly individuals make twice as many outpatient visits per year as those who are under sixty-five years14. The incidence of many (if not most) diseases is age-sensitive and, as a result, patients over sixty-five years of age utilize more inpatient and outpatient services than do younger patients.

3. Medical advances. Most advances in health care have improved outcomes for acute and chronic conditions rather than preventing illness altogether. As a result, Americans are surviving major illnesses, living longer, and using more services during the course of their lifetimes. In addition, as interventions improve, the number of Americans who can potentially benefit from an intervention increases. Thus, procedures that in the past would not have been done on a ninety-year-old patient may now be done safely with positive outcomes.

4. High expectations from the health care system. We have invested billions in new interventions, and Americans, especially the baby-boom generation, which will soon begin to reach the age of sixty-five years, have high expectations for the potential of the health-care system to increase longevity and improve the quality of life.

5. Lifestyle. Lifestyle will have a very important impact on the overall health of Americans. Regrettably, American lifestyle choices, including a poor diet and lack of exercise, are likely to lead to an increase in demand for services in coming years.

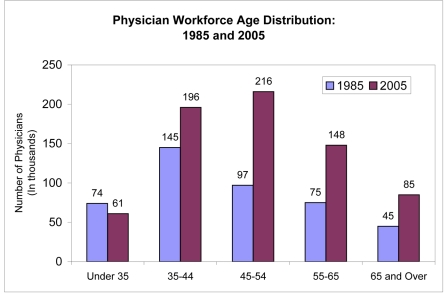

Key Factors Influencing Aggregate Supply

1. The aging of the physician workforce. In large part because the number of graduates from U.S. medical schools doubled between 1960 and 1980 and then stopped growing for twenty-five years, the age distribution of physicians has become older, and we are now facing an increasing number of physicians who are nearing retirement. Currently, one in three active physicians is over the age of fifty-five years; most will retire in the next ten to fifteen years (Fig. 1). With more than 250,000 active physicians over the age of fifty-five years, retirement and activity decisions will have an enormous impact on the future effective supply of physicians. A recent AAMC survey of nearly 9000 physicians over the age of fifty years found that physicians are likely to retire earlier than estimated in previous models; in fact, they tend to retire close to sixty-five years of age, similar to other professionals15.

Fig. 1.

Physician workforce age distribution in 1985 and 2005. Data for 1985 and 2005 are from Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the U.S.59,60 by the American Medical Association (AMA). Note that the data exclude doctors of osteopathy. Active physicians include residents and fellows.

2. Generational and gender changes. The newest generation of physicians appears to be less interested in working the long hours of prior generations of physicians16. This partly reflects the increasing percentage of physicians who are female. Historically, women have worked fewer hours than their male counterparts over the course of their professional life17.

3. International medical graduates. In 2006 to 2007, more than 6800 international medical graduates entered American medicine each year by entering residency training and nearly all stayed after training. This represents one in four physicians entering training, similar to the overall proportion of practicing international medical graduates in the United States. There is growing concern internationally with this draining of human resources from less developed countries to more developed countries18. In addition, the economic development of India (a major source of international medical graduates) and other countries could interrupt this flow of international medical graduates in the future as more donor countries better utilize their health professionals. Other international developments could also disrupt this flow of physicians.

4. Graduate medical education positions. In the absence of a major increase in training (residency and fellowship) positions, the current increase in medical and osteopathic graduates is likely to lead to a decrease in foreign graduates in training rather than an increase in total supply of physicians.

5. Other factors. A wide range of other factors are likely to influence future supply and demand, although it is difficult to estimate when and/or the extent of their impact. For example, if the nation moves to a system of universal health-care coverage, demand is likely to increase; on the other hand, improvements in information technology and productivity could reduce demand. Increased use of evidenced-based medicine could increase or decrease demand for services.

Comparison of System-Wide Supply and Demand

The AAMC analysis (as well as that of the Bureau of Health Professions19) concluded that demand is likely to increase more rapidly than supply, given the current supply and utilization patterns. Almost all likely alternative scenarios lead to projections of even greater shortages. While current utilization is not always appropriate, baseline projections assume that utilization rates by patient demographic data, such as age, gender, and insurance status, will remain unchanged in the future. The AAMC focused on this method rather than on estimating an increase due to increased expectations or a decrease due to improved efficiency.

The 30% increase in medical school enrollment recommended by the AAMC phased in between 2005 and 2015 (and the accompanying growth in graduate medical education) will yield only about 16,000 additional practicing physicians by 2020, far short of the expected shortfall of physicians. Therefore, the AAMC also recommends steps to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the health-care system, such as increased use of information technology and other health professionals.

Applying the AAMC Framework to Orthopaedic Surgery

Applying this framework to individual specialties is very challenging as patients with similar problems may be cared for by physicians from multiple disciplines. For example, many musculoskeletal problems are treated by orthopaedic surgeons and do not require surgical intervention; some of these cases could be treated by other specialists. For baseline projections, the AAMC assumes that, in the future, similar proportions of patients with joint and muscle disorders will be seen by the same specialties currently treating these ailments, including rheumatologists, orthopaedic surgeons, physiatrists, and primary care doctors. For planning purposes, the AAMC assumes (at baseline) that specialists will continue to care for patients at current rates; this is reinforced by the growing literature that suggests that training and certification is highly correlated with patient outcomes20,21.

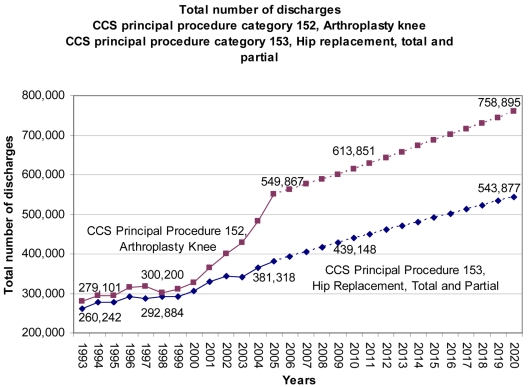

The current utilization rates for orthopaedic surgeons represent, nationally, an average of all geographic areas. This means that while procedure rates for some areas are higher than the national average, others are lower. Future estimates of orthopaedic surgery procedures should apply these average rates to changes in the size and demographic characteristics of the population of the United States. Alternate scenarios can then be modeled to show the potential impact of changing practice patterns. Nationally, the volume of many orthopaedic procedures has continued to grow over the last decade. For instance, the total numbers of hip and knee replacements have climbed rapidly since 2000 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The total number of discharges for knee arthroplasty (CCS [certified coding specialist] principal procedure category 152) and for total and partial hip replacements (CCS principal procedure category 153). The data for 1993 to 2005 are from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample (HCUP-NIS) database for 200561. The data for 2006 to 2020 are projections based on discharges in 2005 per 100,000 population by age group.

Both procedures are heavily concentrated among the elderly; for instance, over two-thirds of hip replacements were received by individuals over the age of sixty-five years. Future rates of replacement will be strongly influenced by the demographic characteristics of the U.S. population and the number of elderly.

Nonsurgical care of the elderly is also likely to drive demand for orthopaedics. In one Dutch population-based study, three-quarters of the people surveyed reported having had musculoskeletal pain during the last year22. Annual incidence rates and severity of complaints only increase with age; almost one-fifth of men and women between the ages of seventy and seventy-nine years reported at least a one-month duration of shoulder pain in the last year23. Moreover, “the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain is much higher than that reported over 40 yr ago,”24 and few health-care providers would expect that musculoskeletal complaints will decrease as the elderly remain active well into their seventh and eighth decades of life.

Supply-Side Factors for Orthopaedic Surgery

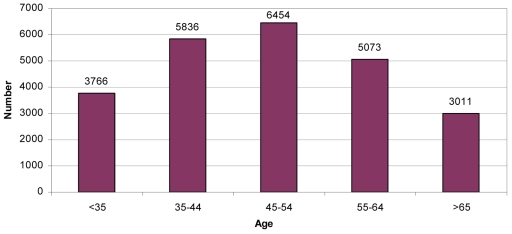

1. The aging of the workforce. The age of the active orthopaedic surgery workforce is similar to that of the physician population, with approximately one-third over the age of fifty-five years and likely to retire by the year 2020 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Age distribution of active orthopaedic surgeons. (Based on data from Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the U.S.59.)

2. Gender and generational changes. Orthopaedic surgery varies from the overall physician population in that women are underrepresented in the specialty and account for only 4.6% of active surgeons (as opposed to 27% of all active physicians). Orthopaedic surgeons are also less likely to be international medical graduates compared with the general physician population (6.9% and 25%, respectively).

Between 1975 and 1995, the number of orthopaedic surgeons doubled to over 22,000, and, currently, there are over 24,000 active physicians in the specialty. While this is similar to growth in other physician specialties, it far outpaced the growth of the U.S. population (which grew only 38% between 1975 and 1995). However, residency positions in orthopaedic surgery have grown only 10% since 1985 to over 600 PGY-1 positions, making it unlikely that current production rates will keep up with overall population growth. In fact, it appears that the orthopaedic surgery workforce is nearing a steady state with as many entering each year as leaving. Nearly 45% of active orthopaedic surgeons are over the age of fifty-five years. With about 600 new entrants per year, this is close to the number estimated to be retiring each year13. This could present a problem, given the growing and aging population and the increasing subspecialization that decreases the flexibility of the orthopaedic workforce to meet evolving needs.

Moreover, while the percentage of women trainees in orthopaedics has grown to 11%, it is still far less than 44%, the average for all female ACGME residents and fellows in 2006 to 2007, making it unclear how the demographics of orthopaedic surgery are likely to change as women gradually become half of the physician workforce. In any case, the growing percentage of orthopaedic surgeons who are female, combined with changing practice patterns by younger physicians, may lead to a decrease in hours worked by orthopaedic surgeons in the future.

Regional variations in the utilization of service across the country somewhat complicate predictions of supply and demand. The AAMC uses national averages in estimating workforce requirements rather than assuming one end of the spectrum represents appropriate care. For example, consider such procedures as knee replacement. Inevitably, total knee replacement will be overperformed in some areas but underperformed in others. Because the current level of evidence and efficiency of utilization review may not allow us to determine the “appropriate” national level, the AAMC uses average procedure rates to estimate future demand.

While we cannot determine whether orthopaedic surgery is likely to face a future shortage or surplus with this limited review, the growing number of elderly individuals, the desire of Americans to remain active well into their later years, and the advances in orthopaedic surgery will most likely place high demands on the orthopaedic surgery workforce and related specialties. It also appears that the supply of orthopaedic surgeons may level off just as the baby boomers begin to reach sixty-five years. Given these realities, it appears to be an appropriate time for the orthopaedic surgery community to undertake a major workforce study to project supply and demand for the next fifteen to twenty-five years.

Potential Pitfalls to the Demand Model: The Dartmouth Response

Workforce Planning—More Sensitive to Demand Than Supply

How many orthopaedic surgeons should we train annually? The simple answer outlined above and proposed by the COGME and the AAMC is to train enough to ensure a supply that matches patient “demand.”25 Unfortunately, the view that market forces can reliably organize an effective and affordable system of health care for musculoskeletal disorders, or for that matter medicine in general, relies on assumptions that have poor face and empirical validity26. Market forces are blind to medical evidence and poorly reflective of patient values. Rather than simply relying on “demand” as an indicator of workforce needs, the specialty must also consider alternatives to relying on wayward markets. By applying knowledge of care effectiveness and patient decision-making, orthopaedic surgery can set up effective systems of care to help dictate workforce requirements.

An important premise in workforce planning for orthopaedic surgeons is that they provide vital emergent and elective care that improves the outcomes of many, but not all, musculoskeletal conditions. Orthopaedic surgeons provide essential care to patients of all ages, across a wide spectrum of congenital, traumatic, and degenerative disorders. Estimating the right number of orthopaedic surgeons for the future is important because the care they provide is essential for the well-being of patient populations.

Projecting the supply of physicians is one necessary component of judging the future adequacy of the workforce. There have been only minor disagreements about future supply estimates. It is accepted that the population is growing and aging, and that the per capita supply of physicians will level off in the next decade or two. The COGME projects that the supply of all full-time-equivalent physicians in 2020 will be between 972,000 and 1,076,000, a modest 11% range of supply. Whether the supply in 2020 is at the low or high side of this projected range is not central to the workforce debate. The crux of the disagreement is on the demand side. Does current patient utilization for physician services, or what COGME terms “demand,” provide us with a guide for estimating future workforce requirements?

Current Usage of “Demand” in Workforce Planning is Misleading

Reliance on economic terms of supply and demand in the language of workforce planning gives the false impression that the care of patients occurs within a “perfect market.” While market forces are powerfully present in the transaction of medical services, as a society we have intentionally interfered with health-care markets in an effort to achieve common societal goals—equitable access to care, quality services, and ultimately improved health.

The price of medical services is one obvious example of our rejection of an unfettered market. Prices have been intentionally blunted to prevent patients from weighing the full cost and benefits of medical care across the full range of goods and services that are available for optimizing well-being, including those that are nonmedical. In a competitive market, patients would pay directly for their care, or at least they would pay directly for their medical insurance. We have largely erased price from health-care transactions because of concerns that price would affect short-term consumer medical care choices and lead to an overall diminution of long-term well-being as necessary care is postponed or patients are left without the means to pay for the other necessities of life. The introduction of copayments is intended to introduce price into the market for medical services, but these out-of-pocket costs are a small proportion of the overall costs.

Relative Absence of Prices Creates a Dilemma

Consider what would occur if the government funded a program to pay for 80% of the cost of automobiles for anyone over the age of sixty-five. Transportation improves everyone's well-being, and more transportation options would lead to better access to all of the other goods and services that we want. Whatever good such a program would offer, the sale of cars would soar and, in the end, we would need to use a metric other than sales as a measure of the need for cars, automotive assembly plants, and autoworkers. Without full price in a market, we must look skeptically at “demand” as the measure of a population's wants and needs, particularly when providers have strong incentives to provide more care.

Subsidies are another domain of interference with the health-care market. Insurance is publicly subsidized, most importantly through Medicare and Medicaid. A wide variety of medical facilities are also subsidized to encourage the provision of care for patients with low socioeconomic status. In rural areas, hospitals and providers are subsidized when markets fail to sustain adequate services. Importantly, the training of physicians is publicly subsidized through support of undergraduate medical education by state legislative appropriations, and of graduate medical education through Medicare.

Interference with health-care services and the physician labor market is necessary because unregulated and unsubsidized health-care markets fail to ensure an adequate provision of high-quality care to the broad population. One of the consequences of this market interference is that we can no longer assume that the current demand for medical services optimizes the outcomes valued by patients. In turn, we cannot assume that the current utilization rates offer a normative guide for the supply of orthopaedic surgeons. In the absence of this normative guide, current training rates could be too low or too high.

Variation in Orthopaedic Care: A Need for a Critical View of “Demand”

Studies of the epidemiology of medical care, including orthopaedic surgery, have consistently shown a mismatch between current practice patterns and the care that patients want or need. As clinicians, we are frequently confronted with two challenges in delivering appropriate levels of care. The first is the lack of high-quality evidence to support a particular course of treatment. The second is the lack of tools to help patients to choose among complex treatment options, particularly when the relative benefits of the options are unknown.

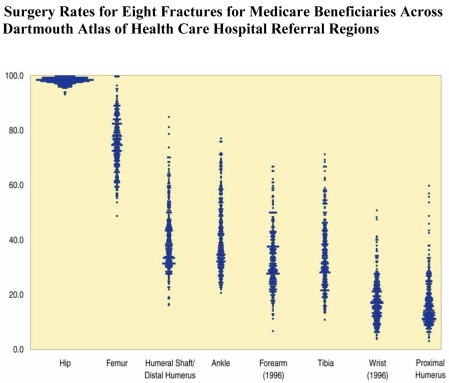

One indication of the lack of consensus in orthopaedic surgery is reflected in the variation in care from region to region27. Figure 4 shows surgery rates for eight different fractures for Medicare beneficiaries across the 306 hospital referral regions in the Dartmouth Atlas of Musculoskeletal Health Care. Note that almost all elderly patients with a hip fracture receive surgical treatment. There is a strong professional consensus that surgery for a hip fracture leads to the best outcome, and virtually all patients receive this care. In this instance, the demand for a medical service equals the needs and wants of the patients.

Fig. 4.

Variations in the use of surgical treatment for eight fractures from 1996 to 1997. Each point represents the proportion of Medicare patients with a fracture who had surgery in each of the 306 hospital referral regions, as reported in the Dartmouth Atlas of Musculoskeletal Health Care27. The use of surgery for hip fracture was the least variable; nearly all hip fractures were treated surgically. The range of variation in surgical treatment of other kinds of fractures was far greater. (Reprinted, with permission, from: Weinstein JN, Birkmeyer JD: Dartmouth atlas of musculoskeletal health care. Chicago: American Hospital Association Press; 2000. p 99.)

However, treatment for the seven other fractures is marked by variations stemming from differing practice styles of orthopaedic surgeons and the “surgical signatures” of communities. Surgery rates for forearm fractures, for example, vary across regions from <20% to >60%. Unlike the data for hip fractures, the relatively uncertain evidence for the positive results of surgery for forearm fractures has led to a lack of professional consensus. In the absence of compelling research to direct treatment, the therapeutic approach is often determined by the beliefs of the treating orthopaedic surgeon. Without evidence for the superiority of a particular treatment, it is difficult to argue that any particular regional rate is “right,” or that the orthopaedic workforce deployed to provide the style of care in a particular region is predicated on patient needs. Thus, variation in “demand” for care offers little guidance for workforce requirements.

An additional example of the lack of consensus for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is seen in the care of osteoarthritis and back conditions. Regional treatment patterns or the surgical signatures for these procedures are very stable over time but are poorly associated with underlying rates of joint and back disease28. There is considerable scientific uncertainty about the value of these procedures. Although a treatment decision can be simplified into the choice of surgical or medical management for a given level of disease severity, the actual establishment of the relative benefits of surgery compared with those of medical care requires randomized clinical trials. These have been almost completely lacking for hip and knee replacement. For back surgery, the results of the SPORT (Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial) study were only recently published29. That study showed that the outcomes of treatment for disc herniation were similar for patients who were initially assigned to surgical treatment compared with those who had medical treatment. In cases in which the benefits of different treatments are similar, patient preferences and values matter, and the truly informed patient can and should serve as the so-called gold standard for demand. Even when solid evidence supports the average benefit of one treatment over an alternative, the final evaluation of the balance between the risks and benefits of each should rest with the patient. When the value of care is uncertain, it is hard to assert that a particular utilization level, or the number of orthopaedic surgeons needed to provide that care, is “right.”

Orthopaedic Care Requires Better Evidence and Informed Patient Choice

Building the evidence base for orthopaedic care is an essential component for reducing unwarranted variation. Yet the current uncertainty of outcomes associated with varied treatment choices will persist as new technologies reach patients before the treatments are fully evaluated. Further, the complexity of randomized clinical trials for orthopaedic procedures dwarfs that of studies used to test most medical therapies.

Even when the outcomes of treatments are known, the best choice in orthopaedic care is not necessarily obvious. For example, the functional outcome of continued medical therapy for joint disease may be inferior to that of surgery in the short term, but it may obviate the need for later revision and its associated higher rate of complications. On the other hand, medical treatment with some nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has recently been associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events. Surgery of the back, hip, or knee each has its own risk of short and long-term complications. The best decision depends not only on knowledge about the probability of the possible outcomes but, most importantly, on the value of the outcomes as viewed by the individual patient. These choices frequently differ across patients and may contravene physician recommendations. For example, a study of 2411 patients in Ontario with severe hip and knee osteoarthritis, who were followed by their primary care physicians, showed that only 16% of the patients were interested in surgery when they were fully informed of the risks and benefits for each treatment choice30.

Decision aids to guide patients through these choices have become increasingly available, but they have been implemented in only a few medical practices. In general, the use of decision aids leads to choices that are better aligned with patient values31 and often, but not always, leads to a reduction of surgical procedure rates32. The full implementation of decision aids would lead to a demand for orthopaedic care that is both wanted and needed by patients.

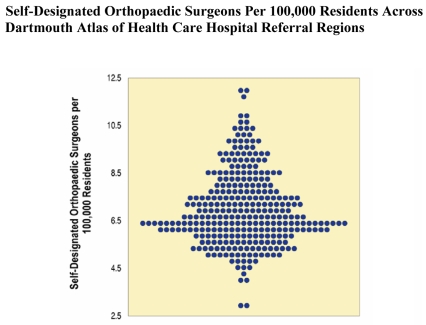

The study of variation in orthopaedic practice shows that the employment opportunities for orthopaedic surgeons are a poor indicator of workforce requirements. Despite the inherent uncertainty of treatment, surgical procedures bring disproportionate financial rewards, and these incentives have encouraged growth in procedurally oriented specialties, including orthopaedic surgery. The weakness of evidence for some types of orthopaedic care, coupled with the strong reimbursement incentives, make it unsurprising that the per capita supply of orthopaedic surgeons varies by >300% across regions (Fig. 5). Surgeons settle in the same places that are attractive to other professionals, and utilization follows.

Fig. 5.

Self-designated orthopaedic surgeons per 100,000 residents in 1999, adjusted for differences in population age, sex, and race. Each point represents one of the 306 hospital referral regions, as reported in the Dartmouth Atlas of Musculoskeletal Health Care27. (Reprinted, with permission, from: Weinstein JN, Birkmeyer JD: Dartmouth atlas of musculoskeletal health care. Chicago: American Hospital Association Press; 2000. p 6.)

The current differences in supply from one region to another place the prediction of an impending shortage of orthopaedic surgeons in perspective. Systems of medical care are relatively adaptable to a wide range of supply because there are many practice styles that improve patient well-being. Indeed, for the same reason, most regions are ignorant about their relative per capita supply of physicians, including orthopaedic surgeons. A 20% difference in the per capita supply of orthopaedic surgeons usually goes unnoticed by either providers or patients as health systems adjust to differing capacities of orthopaedic care. Staff and group-model health maintenance organizations, for example, deploy orthopaedic surgeons at a rate of 55% to 87% less than the overall per capita rate in the United States33, with good patient outcomes and satisfaction of care.

H.L. Mencken once said, “For every problem there is a solution which is simple, clean and wrong.” For the workforce problem, the simple, clean, and wrong solution proposed by the COGME and the AAMC is to enlarge the training capacity for physicians34. Improving orthopaedic care and aligning it with patient values is a more complex, but ultimately a more effective, solution than simply spending more public resources in an attempt to match supply with “demand.”

Regional variation in utilization rates may also be tied to surgeons' increased interest in entering subspecialties. The increasing fragmentation of orthopaedic surgery can be attributed to physicians' compensation and lifestyle concerns, as well as to patients' increased demands for specialized care. In the next two sections of this paper, we examine these workforce issues by first looking at how increased subspecialization and lifestyle concerns are creating shortages in pediatric orthopaedics and, second, by examining the factors that medical students and residents consider when deciding what graduate and fellowship training to pursue.

Subspecialization: A Pediatric Orthopaedic Case Study and Program Director's Concern

The economic model linking demand for physician services to economic expansion focuses on a correlation between income and demand for specialized physician services. Cooper postulated that the demand for life-enhancing treatments and biomedical progress may produce dramatic shortages in specialties and subspecialties in the future4. As physicians become increasingly subspecialized, patients and referring doctors begin to demand specialized services that may not be necessary. This creates an uneven distribution of health-care delivery and complicates physician workforce planning. This pattern has been especially true in pediatric orthopaedics, as there is increasing demand in urban areas for expert surgeons to care for children's orthopaedic problems. Meanwhile, there are many rural areas with few or no pediatric orthopaedic surgeons available. These increased demands for subspecialization are compounded by the fact that the subspecialty is struggling with an aging workforce and a declining pool of applicants.

Pediatric Orthopaedic Demand: Increased Subspecialization

Determining the demand for pediatric orthopaedic expertise is difficult as much of pediatric orthopaedic care in the United States is delivered by other types of orthopaedic surgeons. The ABOS requires six months of pediatric orthopaedics for applicants to become eligible for examination, and thus all orthopaedic surgeons have some pediatric expertise. However, parents and families often request expert pediatric care for their children even if the clinical problem can be addressed by another type of orthopaedic surgeon with less pediatric training.

The demand for increased specialization can be a double-edged sword as once the expectation of pediatric-specific care is established then the demand for that level of expertise must be met. As surgeons get busier within their subspecialty, their willingness to continue seeing patients with problems outside their field of expertise, and to maintain skills and competence in areas outside their subspecialty, diminishes. Surgeons with a very limited scope of practice withdraw from call panels, removing potentially qualified surgeons from the pool of providers available to provide urgent and emergent pediatric orthopaedic care.

Indeed, other types of orthopaedic surgeons are becoming less comfortable in caring for pediatric orthopaedic problems, including urgent problems like fractures and infections. In pediatric referral centers, it is not uncommon to hear referring surgeons state: “I haven't put a spica cast on in years,” or “I am not credentialed to treat children's fractures anymore.” The responsibility for pediatric musculoskeletal trauma call coverage is increasingly falling more and more to pediatric fellowship-trained surgeons. In years past, pediatric orthopaedic fellowships focused on developing expertise in complex, typically elective pediatric conditions, such as clubfoot, scoliosis, and hip dysplasia, and often left fracture care and more common, urgent pediatric problems, such as the management of infections, to the general orthopaedic surgeon. Now pediatric orthopaedic fellowships are training physicians to deal with all aspects of pediatric musculoskeletal conditions, including emergent care. Recent research studies have called for the transfer of pediatric musculoskeletal trauma to pediatric specialists. Injuries previously thought to require emergent care, such as open fractures and supracondylar humeral fractures, have been reported to be safely treated the next day. One study of the impact of trauma care on an urban pediatric orthopaedic practice revealed that fracture care provided about half of the work for the group35.

The medical liability climate also influences decision-making in these areas. In some states, the statute of limitations for the treatment of pediatric patients extends until their eighteenth birthday. Other orthopaedic surgeons concerned about the extended exposure to lawsuits refer patients to pediatric orthopaedic surgeons. The Institute of Medicine has recognized pediatric emergency care as an area of concern in today's health-care system, since children make up 27% of all emergency department visits36. On the basis of these changes within the specialty, pediatric orthopaedic surgery has been recognized by the American Academy of Pediatrics as a surgical shortage area in regard to emergency department coverage37. Many children's centers are hiring and educating midlevel providers to fill this void38. The impact of this change on quality of care, patient satisfaction, and resident-fellow education has not yet been clarified.

Pediatric Orthopaedic Surgeon Supply

While increased demand for subspecialty expertise has contributed to a shortage in pediatric orthopaedic emergent care, the entire subspecialty is struggling with an aging workforce. The Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA) has been described as a “graying” organization. The average age of POSNA members is fifty-two years, contrasted with the average age of self-designated sports medicine specialists in orthopaedic surgery, which is forty-two years. In 2004, 328 POSNA members were forty-five years old or older and only 181 were under the age of forty-five years. The chair of the POSNA Workforce Committee estimates that 25% to 40% of pediatric fellowships went unfilled annually over the last decade39. Many more fellowship opportunities are available today than in the late 1970s, when pediatric orthopaedics first became a recognized subspecialty; however, in a POSNA survey of pediatric orthopaedic fellowship directors, 74% reported a decreasing interest in pediatric fellowships. The number of residents seeking pediatric fellowship training is approximately 3% to 4% of the residents pursuing orthopaedic surgery, or approximately twenty-one to twenty-five residents per year. In 2006 to 2007, twenty-one institutions offered forty-five fellowships, but only twenty-three of these positions were filled. Since 2001, the number of pediatric fellowship positions filled has been between twenty-one and twenty-four per year40. Each year, the ABOS tracks the number of first-time board applicants who self-declare their subspecialist practice. Since 2000, the average number of pediatric orthopaedic surgeons has been around twenty-seven, with a low of sixteen and a high of thirty-three.

POSNA established an ad hoc committee a few years ago to explore workforce issues. An earlier workforce committee had been chaired by Walter Huurman, who proposed six reasons for the shortage of pediatric orthopaedic surgeons: (1) increased fellowship opportunities encourage surgeons to restrict their practice scope; (2) more pediatric fractures are treated operatively, necessitating further expertise; (3) physician extenders are unable to diminish on-call burden; (4) there are too many referrals for minor, self-limited problems; (5) there are heavy inpatient hospital loads; and (6) salary compensation is lower than that in other areas of orthopaedic surgery41. The current POSNA workforce committee offers a slightly different list of reasons for the shortage of pediatric orthopaedic surgeons: (1) the pay differential with other orthopaedic surgeons, (2) work hours, (3) trauma call schedules in children's hospitals, (4) liability risks, (5) dealing with neuromuscular patients, (6) dealing with parents, (7) more women in pediatric orthopaedics who work reduced schedules, (8) high outpatient visit-to-surgery ratio, (9) generational issues of work load and time schedules, and (10) late exposure to pediatric orthopaedics during residency37.

Factors Influencing Resident Career Decisions

To assess the factors that influenced whether orthopaedic residents chose to pursue pediatric orthopaedics, the POSNA workforce committee surveyed ninety-nine fifth-year residents in 200442. Eighty-nine percent reported that they planned to extend their education with fellowship training. The reasons they gave for not pursuing pediatric orthopaedics, in order of response, were as follows:

They liked another subspecialty better.

The ratio of surgical to nonsurgical cases is too small.

The level of relative reimbursement is less than that in other subspecialties.

They do not like caring for handicapped children.

There are limited private practice opportunities.

They do not like dealing with parents.

The liability is too great.

In general, pediatric orthopaedics is a difficult sell within the house of orthopaedics because compensation is less than that in other subspecialty areas, and it has a more demanding call responsibility than other subspecialties. The mean net income of all orthopaedic surgeons in the 2006 Orthopaedic Physician Census conducted by the AAOS was $394,000, including full and part-time practicing surgeons12. However, on a search firm's Internet site, pediatric orthopaedics was listed near the bottom of the salary range. Spinal surgery was listed first with a salary of $554,000, followed by joint replacement with a salary of $476,000, hand surgery at $387,000, and pediatric orthopaedics at $355,00043. Prospective students and residents thus see pediatric orthopaedics as a subspecialty with one of the lowest salaries and highest call burdens, which may be impacting their decision to not pursue a career in pediatric orthopaedic surgery.

Resident and Medical Student Pipeline: A Resident Response

If indeed there is a growing disparity between the numbers of physicians choosing to enter orthopaedic surgery subspecialties, then it is critical to address this issue early in the educational model. With the proper mentoring and attention from some of our dynamic leaders, more medical students and residents can be drawn into the orthopaedic pipeline and be directed toward subspecialties, such as pediatric orthopaedics, that appear to be experiencing shortages.

Orthopaedic surgery residents choose to enter subspecialties for numerous reasons. Many residents want to improve their “marketability” in seeking a job after graduate medical education. Fellowship training may enable them to join a physicians' group as a specialist. Others may seek further training in a particular area to address deficiencies in their own residency educational curricula. For example, many programs still have insufficient faculty and clinical volume to train residents in tumor or foot and ankle surgery. Lastly, many people pursue a fellowship in a particular field because, simply, it is what interests them and they have been committed to it for some time. Of the 90% of orthopaedic surgery residents who ultimately pursue fellowship training, a large and important component of this group remains undecided early in their orthopaedic surgery training as to which specialty they will pursue, and they are not driven by one of the aforementioned reasons. Medical student and resident career choices are guided by personal interest in the subject, financial considerations (salary potential and debt), and lifestyle (working hours and call responsibilities). The most controllable—and often most overlooked—reason for resident career decision-making is the influence of mentors and prior clinical experience. Not surprisingly, many residents chose orthopaedic surgery as a career because they were influenced or inspired by a clinical exposure to the field, or by an individual faculty member who spent time with them. Exposure to good teachers has been shown to have a positive influence on student career choices44. Positive associations with dynamic, interactive individuals expressing pride and enjoyment with their jobs is a powerful motivating force. Indeed, many of the reasons why residents change their career paths during residency are the result of clinical experiences with faculty while on specific rotations. The magnitude of this effect cannot be overstated. Residents, like members of any other profession, will be influenced by and will gravitate toward other individuals who appear satisfied, productive, and happy with their own careers, as it gives them the clearest prediction of what their own career and life might resemble. A program that has a disproportionately high number of graduating residents seeking fellowship training in orthopaedic oncology, for example, more often than not will have oncology faculty who received excellent reviews from residents. Similarly, a program that rarely produces an individual seeking training in a specific subspecialty should review how that particular discipline is taught and structured.

A number of studies in the literature have highlighted the importance of faculty and clinical experience in the attitude of residents and students toward certain disciplines. Bernstein et al. showed a 12% increase in residency applications to orthopaedic surgery in medical schools with a required exposure to musculoskeletal medicine45. This impact was even more pronounced for women and minority ethnicities, subgroups that traditionally are underrepresented within orthopaedic surgery. Chung et al. conducted a national survey using an Internet questionnaire in an attempt to identify factors that influenced graduating chief residents to commit to a hand fellowship46. This survey found that the effect of interaction with an attending surgeon was a key factor in the residents' decision-making and even substantively affected first-year medical students—many of whom were just recent graduates from college47.

Residents also play a key role in influencing medical students' career decisions. They frequently have more time to spend with students, particularly while on call. Several studies have highlighted the critical role that residents have in their interaction with and education of students48. Student questionnaires and feedback surveys from these studies have indicated that students perceived residents, more so than attending physicians, as the responsible teachers for their third-year clerkships49 and credited them for making important contributions to their experiences50. Rewarding and acknowledging our faculty and resident leaders who are consistently cited as excellent teachers are critical in helping to build and maintain the orthopaedic surgery pipeline.

Practically speaking, finances and reimbursement also play an important role in shaping the decision-making of our current generation of residents and students. Barbieri et al. found that economic factors were associated with the percentage of specialty positions filled by graduates of U.S. medical schools in the 2004 NRMP match data51. For example, >90% of the positions in some of the highest paying specialties, such as neurosurgery, orthopaedic surgery, dermatology, and plastic surgery, were filled by U.S. medical graduates; conversely, <60% of the positions in internal medicine and family practice were filled by U.S. graduates. The increasing cost of medical education may influence some residents to choose more lucrative careers in order to pay off their debts. As hospitals and outpatient surgery centers place greater emphasis on procedure-based specialties, this also has the potential to influence residents. Finally, as mentioned previously, concerns about malpractice liability in pediatric orthopaedic surgery and trauma may dissuade residents and students from entering these specific fields.

Lifestyle considerations are also becoming increasingly important to young doctors, residents, and students52-54. A survey of graduating U.S. medical students between the years 1996 and 2002 found that, after controlling for income, 55% of the variability in specialty preference was attributable to the desire for controllable lifestyle and work hours and the amount of years of graduate medical education required55. Dorsey et al. found that controllable lifestyle issues accounted for most of the variability in the career choices of graduates after controlling for other variables. Lifestyle factors are increasingly important as more women enter surgical careers wanting to have families. While Azizzadeh et al. found that deterrents to surgery as a career choice included concerns about lifestyle and work hours during residency56, the change in mandatory duty-hour regulations has led some students, who otherwise might never have done so, to consider surgical careers57. Having more time to spend with family, built-in administrative or research time, and some level of control over call frequency play sizable roles in the happiness and attitude of students choosing various careers.

In summary, if we want to address supply imbalances within orthopaedic surgery subspecialties, we must consider how our residents and medical students make career decisions. Students and residents need to have exposure to enthusiastic teachers who are orthopaedic surgeons. Current residents should be informed about the need for specific subspecialties and the excellent jobs and/or careers available. Regional referral systems should be developed to allow a systematic approach to meet the demands and needs of patients, referring physicians, and outlying hospitals. These centers can consolidate available orthopaedic talent and address some of the lifestyle and call burden issues. Surgeons can also work with hospitals to address compensation issues and resource allocation for programs with a high on-call burden. At a governmental level, lobbying for liability reform and improved reimbursement for nighttime and weekend work would increase the economic incentives for surgeons to provide urgent and emergent care.

Overview

In this paper, we attempted to outline some of the most important considerations facing the orthopaedic specialty physician workforce in the next ten to twenty years. While we cannot determine for certain whether orthopaedic surgery will face a shortage or a surplus in the future, current market forces, the aging of the baby-boomer generation, and the recent calls by the AAMC and COGME for medical school expansion certainly suggest that there is cause for concern.

The question that the specialty must address is how and to what level we should respond to the predicted shortage. Immediately following the most recent Annual Meeting of the AOA, members were polled by an electronic rapid audience-response survey to gather opinions about the predicted physician workforce shortage. The audience of nearly 100 people consisted of department chairs (25%), program directors (25%), faculty (41%), and residents (9%). Eighty-four percent thought that new advances in medicine over the next ten years will likely lead to an increase in demand for orthopaedic procedures, and 67% thought that the new advances in medicine will lead to even further subspecialization within the field. Accordingly, 69% of the audience supported the proposal that the orthopaedic surgery Residency Review Committee take a proactive role in increasing the number of residency positions as long as the quality of each program does not suffer58.

Using NRMP and AAMC data, we are able to measure the supply of orthopaedic physicians with relative accuracy. However, since health care is not a perfect market, we cannot be certain that the level of projected demand is accurate, and we must be careful not to overrespond to calls for an increased supply of orthopaedic surgeons. Third-party payers and patient and physician preferences play key roles in determining demand, which means that patient demand is not necessarily evidence-based, economically sensitive, or synonymous with patient need. This is particularly true for non-life-threatening, lifestyle-limiting diseases, which are very common in orthopaedic surgery.

With very few evidenced-based studies to demonstrate which techniques or procedures are most effective, patients rely on the advice and preference of their individual physician and surgeon, leading to discrepancies between practice patterns and utilization rates across the country. Indeed, 60% of the AOA audience thought that, as the national supply of orthopaedic surgeons increases, regional variation in the per capita supply would remain the same, with many more surgeons settling into areas already in high supply. Sixty percent of the audience believed that musculoskeletal health status, insurance coverage, age, or patient preferences for orthopaedic services did not explain any regional variation in the orthopaedic surgery workforce in any particular region. A startling 86% of the responders thought that sports medicine is the most oversupplied subspecialty, while 59% of the audience thought that pediatric orthopaedic surgery is the most undersupplied. Trauma (17%) and oncology (8%) were a distant second and third among those that were thought to be most undersupplied.

Arguably, the problem may not be that we have a shortage of orthopaedic surgeons but rather that physician and patient preferences create an inflated demand for specialized services, which leads to an oversupply of surgeons in some subspecialties and an undersupply in others. If the health-care system were more rational, these shortages and discrepancies between subspecialties would not exist. However, short of overhauling the entire health-care system or creating a system of physician rationing, it is unlikely that the imperfections of the health-care system will be addressed in the next ten to fifteen years.

As a specialty, we must work toward expanding evidenced-based care by developing and disseminating effectiveness studies. We should also explore other options for dealing with the potential workforce shortage. These include encouraging physicians to work additional years, promoting efficiency and productivity, and possibly even modifying the scope of services that we provide. However, the easiest and most cost-effective approach is providing guidance and mentorship of our current residents and medical students. When asked how they chose their specialty, 80% of the AOA audience members responded that the single most important factor in their personal decision was the influence of a specific mentor in medical school or residency. Therefore, the most immediate initiative that we, as a specialty, can accomplish is to mentor and encourage our residents to subspecialize in areas of orthopaedic surgery that we believe are underserved.

As outlined in the paper, even without mandates from organized medicine, government, or industry, there will be at least a 15% increase in the number of graduating orthopaedic surgeons in the next five to ten years. It may take many more years until this increase has a substantial impact on total supply. This 15% increase, combined with initiatives to move current residents and fellows into underserved specialties and a concerted effort to improve evidence-based care, will go a long way toward not only addressing the predicted physician shortage but also developing a more rational health-care system that better meets the future health-care needs of orthopaedic surgery patients.

Acknowledgments

Note: The authors thank Kelly Smith, MPP, Communications Manager, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, for editing this article, and William Hart, Accreditation Administrator, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, for compiling resident data and statistics.

This report is based on a symposium presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Orthopaedic Association on June 16, 2007, in Asheville, North Carolina.

Disclosure: In support of their research for or preparation of this work, one or more of the authors received, in any one year, outside funding or grants in excess of $10,000 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institute on Aging. Neither they nor a member of their immediate families received payments or other benefits or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from a commercial entity. No commercial entity paid or directed, or agreed to pay or direct, any benefits to any research fund, foundation, division, center, clinical practice, or other charitable or nonprofit organization with which the authors, or a member of their immediate families, are affiliated or associated.

References

- 1.Association of American Medical Colleges. Statement on the physician workforce. 2006. Jun. http://www.aamc.org/workforce/workforceposition.pdf. Accessed 2007 Dec 19.

- 2.Heckman JD, Lee PP, Jackson CA, Relles D, Weinstein JN, Gebhardt MC, Simon MA, Callaghan JJ, D'Ambrosia RD. Symposium. Orthopaedic workforce in the next millennium. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1533-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. RAND study finds surplus orthopaedists now, 2010. AAOS Bulletin. 1998. Apr. www2.aaos.org/aaos/archives/bulletin/apr98/acad3.htm. Accessed 2007 Mar 17.

- 4.Cooper RA. Weighing the evidence for expanding physician supply. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:705-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center for Workforce Studies; Association of American Medical Colleges. Recent studies and reports on physician shortages in the US. 2007. Aug. http://www.aamc.org/workforce/recentworkforcestudies2007.pdf. Accessed 2007 Dec 19.

- 6.National Resident Matching Program. Advance data tables for 2007. main residency match. http://www.nrmp.org/advancedata2007.pdf. Accessed 2007 Jul 31.

- 7.National Resident Matching Program; Association of American Medical Colleges. Charting outcomes in the match: characteristics of applicants who matched to their preferred specialty in the 2007. NRMP main residency match. 2nd ed. 2007 Aug. http://www.nrmp.org/data/chartingoutcomes2007.pdf. Accessed 2007 Aug 20.

- 8.Association of American Medical Colleges. ERAS program statistics. http://www.aamc.org/programs/eras/programs/statistics/start.htm. Accessed 2007. Aug 20.

- 9.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education statistics. Personal communication with William Hart. 2007. Feb 24.

- 10.Gebhardt MC. Orthopaedic workforce issues from the perspective of the Residency Review Committee and the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery, Incorporated. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1539-41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Osteopathic Academy of Orthopedics website. http://www.aoao.org. Accessed 2006. Dec 5.

- 12.American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery. Personal communication with Patsy Furr. 2007. Mar 29.

- 13.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Orthopaedic practice in the US 2005-2006. Final report. 2006 Jun.

- 14.Salsberg E, Grover A. Physician workforce shortages: implications and issues for academic health centers and policymakers. Acad Med. 2006:81:782-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hing E, Cherry DK, Woodwell DA. National ambulatory medical care survey: 2004 summary. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 374. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Care Statistics; 2006. [PubMed]

- 16.Erikson C. Results of the AAMC/AMA surveys of physicians over and under 50. Presented at the Third Annual AAMC Physician Workforce Research Conference; 2007. May 2-4; Bethesda, MD.

- 17.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, Bruinooge S, Goldstein M. Future supply and demand for oncologists: challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:79-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullan F. The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health Resources and Services Administration. Physician supply and demand: projections to 2020. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/physiciansupplydemand/default.htm. Accessed 2007 Dec 19.

- 20.Norcini JJ, Kimball HR, Lipner RS. Certification and specialization: do they matter in the outcome of acute myocardial infarction? Acad Med. 2000;75:1193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shea JA, Norcini JJ, Kimball HR. Relationships of ratings of clinical competence and ABIM scores to certification status. Acad Med. 1993;68(10 Suppl):S22-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wijnhoven HA, de Vet HC, Picavet HS. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders is systematically higher in women than in men. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:717-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogt MT, Simonsick EM, Harris TB, Nevitt MC, Kang JD, Rubin SM, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB; Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Neck and shoulder pain in 70- to 79-year-old men and women: findings from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Spine J. 2003;3:435-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harkness EF, Macfarlane GJ, Silman AJ, McBeth J. Is musculoskeletal pain more common now than 40 years ago?: two population-based cross-sectional studies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44:890-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Council on Graduate Medical Education. Sixteenth report. Physician workforce policy guidelines for the United States, 2000-2020. 2005 Jan.

- 26.Weinstein JN, Goodman D, Wennberg JE. The orthopaedic workforce: which rate is right? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:327-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein JN, Birkmeyer JD, editors. The Dartmouth atlas of musculoskeletal health care. Chicago: AHA Press; 2000. [PubMed]

- 28.Weinstein JN, Bronner KK, Morgan TS, Wennberg JE. Trends and geographic variations in major surgery for degenerative diseases of the hip, knee, and spine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Web Exclusives:VAR81-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson AN, Hanscom B, Skinner JS, Abdu WA, Hilibrand AS, Boden SD, Deyo RA. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2441-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, Williams JI, Harvey B, Glazier R, Wilkins A, Badley EM. Determining the need for hip and knee arthroplasty: the role of clinical severity and patients' preferences. Med Care. 2001;39:206-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Rovner D, Holmes-Rovner M, Tait V, Tetroe J, Fiset V, Barry M, Jones J. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Wagner EH, Barrett P, Barry MJ, Barlow W, Fowler FJ Jr. The effect of a shared decisionmaking program on rates of surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Pilot results. Med Care. 1995;33:765-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiner JP. Prepaid group practice staffing and U.S. physician supply: lessons for workforce policy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Web Exclusives:W4-43-59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Goodman DC. Do we need more physicians? Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Web Exclusives:W4-67-69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Ward WT, Rihn JA. The impact of trauma in an urban pediatric orthopaedic practice. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2759-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McHugh M, Slavin P; Institute of Medicine. The future of emergency care. 2007. May 17. www.iom.edu/CMS/3809/34454/43123.aspx. Accessed 2007 Jul 7.

- 37.Smith BA. POSNA workforce symposium. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America; 2007. May 24; Hollywood, FL.

- 38.Mubarak S. Pediatric workforce symposium. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America; 2007. May 24; Hollywood, FL.

- 39.Smith BA. Personal communication. 2006. Dec.