Abstract

Nickel compounds are carcinogenic to humans and have been shown to alter epigenetic homeostasis. The c-Myc protein controls 15 % of human genes and it has been shown that fluctuations of c-Myc protein alter global epigenetic marks. Therefore, the regulation of c-Myc by nickel ions in immortalized but not tumorigenic human bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells was examined in this study. It was found that c-Myc protein expression was increased by nickel ions in non-tumorigenic Beas-2B and human keratinocyte HaCaT cells. The results also indicated that nickel ions induced apoptosis in Beas-2B cells. Knockout of c-Myc and its restoration in a rat cell system confirmed the essential role of c-Myc in nickel ions induced apoptosis. Further studies in Beas-2B cells showed that nickel ion increased the c-Myc mRNA level and c-Myc promoter activity, but did not increase c-Myc mRNA and protein stability. Moreover, nickel ion upregulated c-Myc in Beas-2B cells through the MEK/ERK pathway. Collectively, the results demonstrate that c-Myc induction by nickel ions occurs via an ERK-dependent pathway and plays a crucial role in nickel-induced apoptosis in Beas-2B cells.

Keywords: Nickel, c-Myc, Apoptosis, ERK

Introduction

Nickel compounds have been found to be carcinogenic based upon epidemiological, animal and cell culture studies (Doll et al., 1970; Kerckaert et al., 1996; Kuper et al., 1997; Miller et al., 2001). Nickel and its compounds are widely used in modern industry in conjunction with other metals for the production of alloys for coins, jewelry, and stainless steel; they are also used for plating, battery production, as a catalyst, etc. Nickel compounds can enter the body through inhalation, ingestion, and dermal absorption (Grandjean, 1984). Occupational exposure to nickel compounds has been associated with respiratory distress, lung and nasal cancer (Doll et al., 1970); however, the mechanisms by which nickel exposure causes toxicity and cancers remain unclear.

Although nickel compounds are carcinogenic, generally they have been shown not to be mutagenic (Biggart and Costa, 1986; Biedermann and Landolph, 1987). Previous studies have found that nickel compounds induced gene silencing by epigenetic mechanisms such as, altering global DNA methylation levels and histone modifications, which may contribute to tumorigenesis (Lee et al., 1995; Lee et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2006; Ke et al., 2006). Recent studies demonstrated that c-Myc inactivation induced global changes in chromatin structure associated with a marked reduction of histone H4 acetylation and increased histone H3 K9 methylation (Wu et al., 2007). Thus, it was of interest to study the effects of nickel ions on c-Myc, and the role it played in nickel-induced toxicity and carcinogenesis.

c-Myc belongs to the Myc family of transcription factors. By modifying the expression of its target genes, c-Myc results in numerous biological effects, including driving cell proliferation, regulating cell growth, apoptosis, differentiation, stem cell self-renewal, senescence, angiogenesis, metabolism, DNA damage response and genetic stability (Luscher and Larsson, 2007).

c-Myc mRNA and protein are generally expressed at low levels in normal proliferating cells (Rudolph et al., 1999), but frequently overexpressed in cancer cells (Hann and Eisenman, 1984). This enhanced and/or constitutive c-Myc expression is sometimes the result of mutations in the c-Myc locus (e.g., Burkitt’s lymphoma) (Taub et al., 1982) or at other times in the signal transduction pathways that regulate c-Myc expression. However, control of c-Myc expression occurs in multiple levels, including regulation of the c-Myc promoter activity, transcription initiation and elongation, translation, and the stability of mRNA and protein (Dani et al., 1984; Hann et al., 1988; Hann, 1994; Hann, 2006). The half life of c-Myc is very short in quiescent cells due to proteasomal degradation (Bartholomeusz et al., 2007); however, upon serum stimulation and cell cycle entry, c-Myc becomes transiently stabilized by Ras pathways, allowing it to accumulate to high levels (Hann et al., 1985; Sears et al., 1999).

Numerous signal transduction pathways are involved in the control of c-Myc transcription. For instance, various mitogenic signals such as Wnt (Sansom et al., 2007) and EGF activate c-Myc transcription via the Ras/MEK/ERK pathway (Bermudez et al., 2008); IL-2 induced c-Myc expression via the PI3K/Akt pathway (Ahmed et al., 1997). However, the generation of a specific signal and its outcome depend largely on the cell type and context as well as on the developmental or physiological state of a cell.

Current study has investigated the effects of nickel ions on c-Myc in the non-tumorigenic Beas-2B cell line, the role that c-Myc plays in nickel-induced toxicity or carcinogenesis, and the mechanism by which nickel compounds dysregulate c-Myc. The results of this study may provide valuable information for the prevention and treatment of occupational diseases caused by nickel exposure.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

Human bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells, human keratinocyte HaCaT cells, TGR-1 (c-Myc+/+), HO15.19 (c-Myc−/−) and HOmyc3 (HO15.19 with reconstituted c-Myc expression) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen). TGR-1, HO15.19 and HOmyc3 are all derivatives of the Rat-1 cell line (Mateyak et al., 1999). All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, ATLAS Biological, Fort Collins, CO), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Grand Island, NY). Cells were maintained at 37°C as monolayers in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Chemicals and antibodies

The following antibodies were used: c-Myc (N-262), phosphor-ERK1/2 and PARP antibody (Santa Cruz) and α-tubulin antibody (Sigma). Primary antibody-bound proteins were detected by using appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and an enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL for HRP) Western blotting system (from Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). NiSO4, Actinomycin D and cycloheximide were from sigma. SP600125 (JNK inhibitor), LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor), SB203580 (p38 inhibitor), and PD98059 and U0126 (both are ERK/MEK inhibitors) all were from Calbiochem Biochemicals (Gibbstown, NJ). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise specified.

Western blot

~8×105 cells were seeded in a 60 mm dish. The next day cells were treated with nickel ions for the selected time. Cells were then washed with ice-cold 1×PBS twice and lysed with ice-cold radioimmuno-precipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, PH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.25%Na-deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN) for 10 min on ice, followed by further disrupting cells by repeated aspiration through a 21 gauge needle. The cells were then transferred to an Eppendorf tube and kept on ice for another 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 10000 x g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and the concentration of protein was measured using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were separated by a SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to a PVDF membrane and probed with a specific antibody against the target protein. The target protein was then detected using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and an ECL Western blotting system.

Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis

~2.5 ×106 cells were seeded in a 100 mm dish. The next day, cells were treated with nickel ions for 24 h. Both adherent and floating cells were then collected, washed, and fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol at −70°C overnight, and stained with 1 ml of 50 μg/ml propidium iodide containing 20 μl of 25 mg/ml RNase A and incubated 15 min at room temperature in the dark. DNA content was analyzed using flow cytometry (Epics XL FACS, Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL). Apoptotic cells have a higher amount of subdiploid DNA which accumulates in the pre-G1 position of the cell cycle profiles.

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

~8×105 cells were seeded in a 60 mm dish. The next day cells were treated with nickel ions for 24 h. RNA was then isolated from cells with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer. The quality of the isolated RNA was checked by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel, and concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm. Either 0.5 or 1 μg of RNA was then reversed transcribed to cDNA with the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis Super-Mix Kit for qRT-PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Semi-quantitative PCR was performed to amplify c-Myc and β-actin using the following primer pairs: c-Myc: 5’-TACCCTCTCAACGACAGCAG-3’ (forward) 5’-TCTTGACATTCTCCTCGGTG-3’(reverse); β-actin: 5’-TCACCCACACTGTGCCCA TCTACGA-3’ (forward), 5’-CAGCGGAACCGCTCATTGCCAATGG-3’ (reverse). 0.5 or 1 μl was used in a final volume of 50 μl PCR reaction mix containing both the forward and reverse primers, dNTPs (10 mM, 1 μl each), 10× Reaction buffer (5 ml), and 2U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The conditions for PCR are: 95°C for 1 min, followed by 23 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 54°C, and 1 min at 68°C. An aliquot of the PCR product was analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel.

RNA stability

~8×105 cells were seeded in a 60 mm dish. The next day NiSO4 was added and left on the medium for 16 h, then Actinomycin D was added to a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. Cells were then lysed following selected time periods and the RNA was isolated.

Luciferase reporter assay

Beas-2B cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a final density of 5x104 cells per well 24 h before transfection. Cells were then co-transfected with 100 ng of the c-Myc promoter construct [P2 (−2489)-luc, (Lee and Ziff, 1999)] and 5 ng of pRL-TK Renilla luciferase construct, and incubated with increasing levels of soluble nickel (NiCl2) for 40 h. The cells were lysed and luciferase activities were measured with dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The firefly luminescence signal was normalized based on the Renilla luminescence signal. The experiment was performed at least three times in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times and representative data are shown. Data in the graph are given as mean values ± standard error of the mean. Statistical differences were calculated by using the two-tailed Student’s t-test with error probabilities of p <0.05 to be significant.

Results

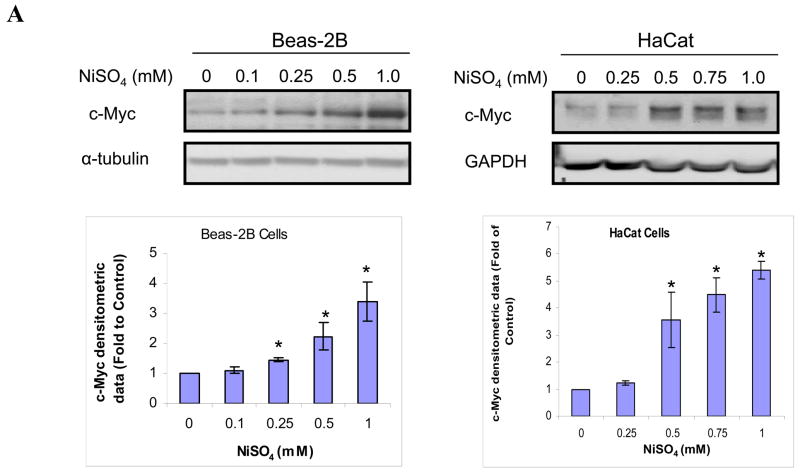

Nickel ions up-regulated c-Myc protein in non-tumorigenic cells

We have studied the effects of nickel ions on the c-Myc protein expression in immortalized but not tumorigenic human bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells and human keratinocyte HaCaT cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, c-Myc protein level was increased by NiSO4 in Beas-2B and HaCat cells in a dose-dependent manner after 24 h exposure. Furthermore, Fig. 1B showed that both 0.25mM and 1mM of NiSO4 significantly up-regulated c-Myc protein in Beas-2B cells in a time-dependent manner.

Figure 1.

Nickel ions increased c-Myc protein in immortalized, non-tumorigenic cell lines. (A) Cells were treated with NiSO4 at indicated concentrations for 24 h; (B) Cells were treated with 0.25 and 1.0 mM NiSO4 for 6, 12 and 24 h. After treatment, cells were lysed and whole cell lysate was analyzed by Western blot. The upper panel is a representative blot while the lower panel is the densitometric data normalized to α-tubulin or GAPDH given as fold-control using two tailed Student’s T-test. Data are expressed as mean + SE in panel A, or mean + SE in panel B, obtained from three independent experiments. * Statistically significantly change (P < 0.05) when compared to samples without nickel treatment.

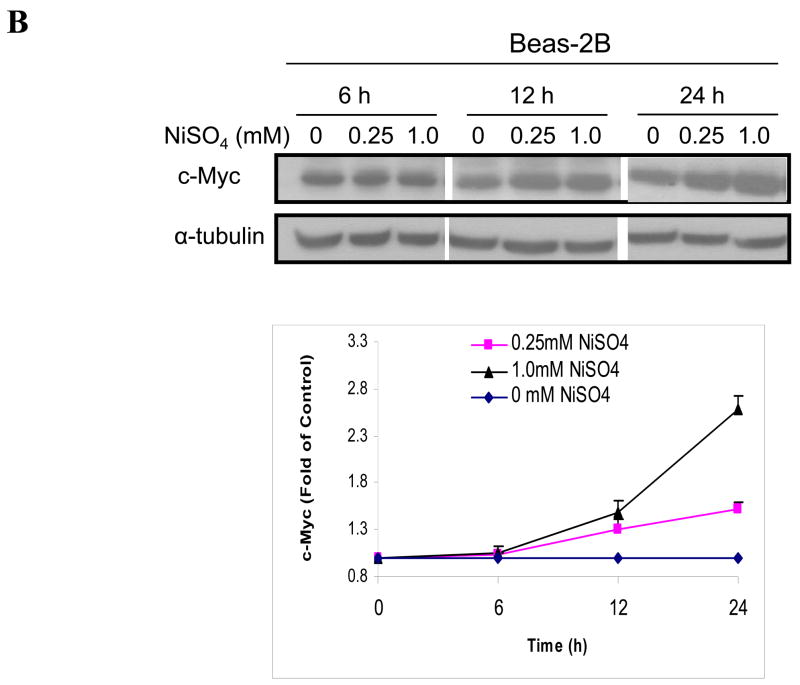

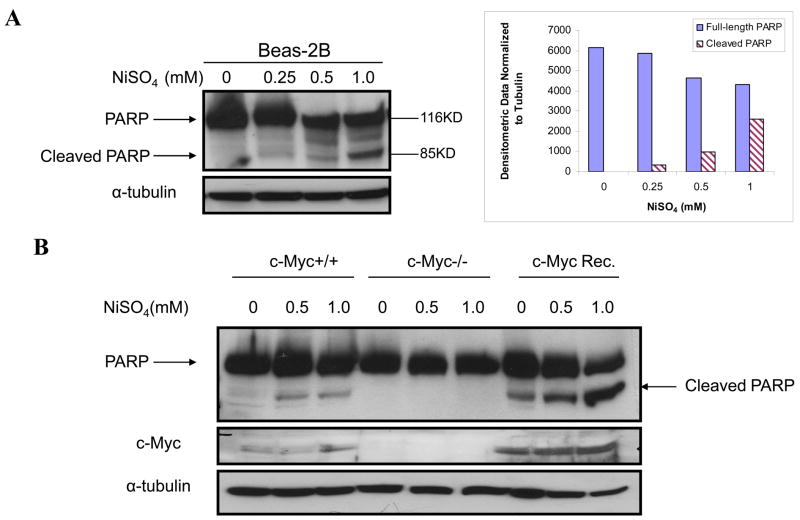

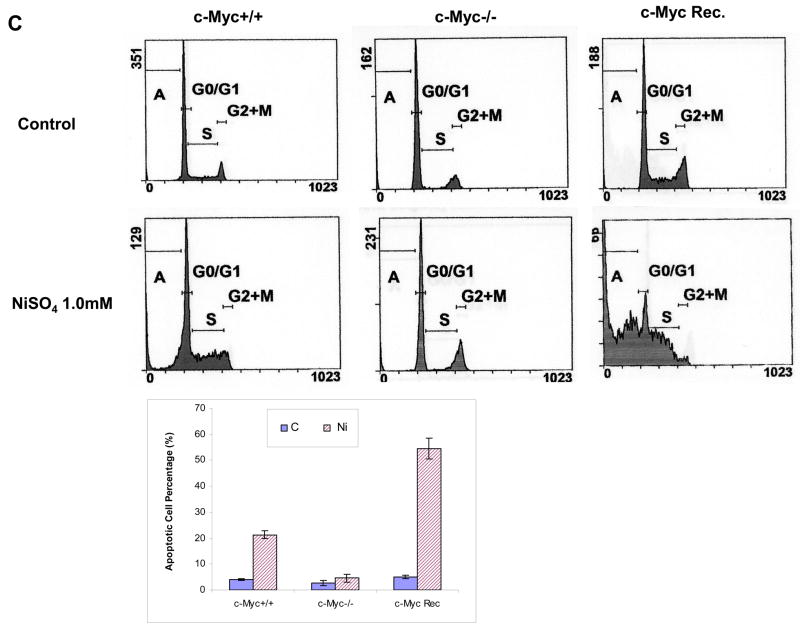

Nickel ions induced apoptosis that is dependent on c-Myc in non-tumorigenic Beas-2B cells

To study the role which c-Myc may play in nickel toxicity or carcinogenesis, we investigated the biological significance of c-Myc dysregulation by nickel ions. In view of the central role of c-Myc in cell growth regulation, cell apoptosis was investigated following NiSO4 exposure. Beas-2B cells were treated with selected concentrations of NiSO4 for 24 h and then whole cell lysates were isolated to determine poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage. PARP is a 116 KD nuclear chromatin-associated enzyme that is cleaved during apoptosis by caspase-3 into a 24 KD fragment containing the DNA binding and an 89 KD fragment containing the catalytic and automodification domain, so PARP cleavage represents a marker for cell apoptosis. It was found that 0.5mM and 1mM of nickel ions significantly induced PARP cleavage in Beas-2B cells, suggesting NiSO4 exposure induce apoptosis in Beas-2B cells. Secondly, in order to determine whether nickel-induced apoptosis in Beas-2B cells was dependent upon c-Myc activation, the Rat-1 cell lines (wild type Rat-1 cells: TGR-1, c-Myc knockout Rat-1 cells: HO15.19, and HO15.19 with reconstituted c-Myc expression: HOmyc3) (Mateyak et al., 1999) were treated with 0.5 and 1.0 mM NiSO4 for 24 h, and then c-Myc and cleaved PARP were measured by Western blot. The results showed that nickel ions also increased c-Myc protein level in Rat-1 wild type cells, indicating similar effect in Beas-2B cells (Fig.2B). In addition, nickel ions were found to induce PARP cleavage in wild type Rat-1 cells but not in c-Myc knockout cells, and nickel ions induced a much higher level of cleaved PARP in the c-Myc reconstituted cells, which have higher c-Myc protein than wild type cells. These results indicated that nickel ions induced apoptotic effects in Rat-1 cell line and that was dependent upon c-Myc (Fig. 2B). To further establish that authentic apoptosis was associated with activation of c-Myc by nickel ions, flow cytometric analysis was utilized to measure apoptosis (Fig. 2C). Flow cytometry analysis also showed a dependency of apoptosis upon c-Myc, supporting the data obtained with PARP (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Nickel ions induced apoptosis is mediated by c-Myc in Beas-2B cells. (A) Beas-2B cells were treated with NiSO4 at indicated concentrations for 24 h. The cells were then lysed and subjected to Western blot analyzing. The left panel is a representative blot while the right panel is the densitometric data normalized to α-tubulin. (B) TGR-1 (c-Myc+/+), HO15.19 (c-Myc−/−) and HOmyc3 (HO15.19 with reconstituted c-Myc expression) were treated with NiSO4 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h. The cells were then lysed using RIPA buffer and whole cell lysate was isolated for Western blot. (C) TGR-1 (c-Myc+/+), HO15.19 (c-Myc−/−) and HOmyc3 (HO15.19 with reconstituted c-Myc expression) were treated with 1.0 mM NiSO4 for 24 h, and then cells were collected and stained with propidium iodide. DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry, and a representative cell cycle profile was shown in the upper panel. The bottom panel is the apoptotic cell percentage, which is expressed as mean + SE, obtained from three independent experiments.

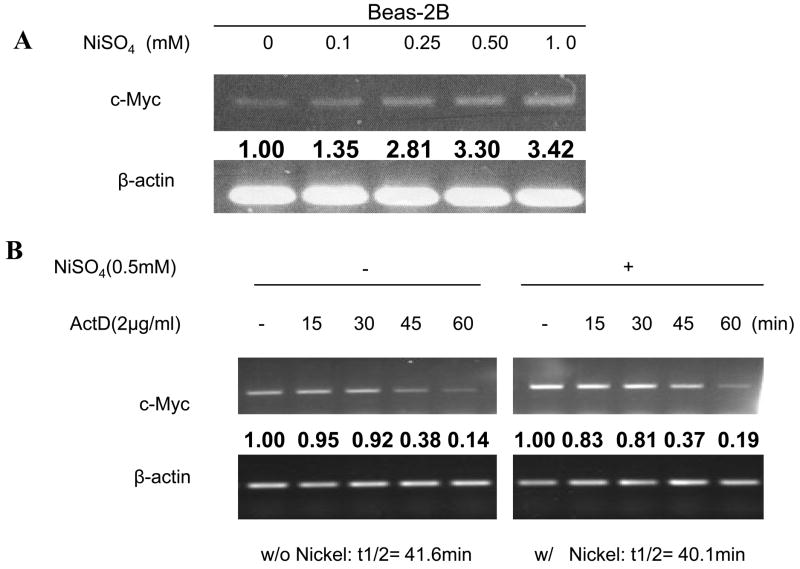

Nickel ions induced c-Myc transcription in Beas-2B cells

As described above, cells have multiple mechanisms to tightly control c-Myc protein expression. To investigate the nature of the molecular mechanism by which nickel ions affect c-Myc protein expression, the transcription, translation, and c-Myc mRNA stability were studied following nickel ions exposure. As shown in Fig. 3A, nickel ions significantly induced c-Myc mRNA level in Beas-2B cells in a dose-dependent manner. To determine whether the increased c-Myc mRNA was due to an effect of nickel ions on mRNA stability, cells were exposed to both actinomycin D (ActD) to inhibit cellular global transcription, and to NiSO4, followed by a measurement of the mRNA with semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Fig. 3B shows that nickel ions had no significant effect upon the stability of c-Myc mRNA in Beas-2B cells. To examine whether nickel ions acted upon the c-Myc promoter, a luciferase reporter assay using the c-Myc promoter was studied in Beas-2B exposed to nickel ions. Luciferase activity was significantly increased by nickel ions in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 3C), indicating that nickel ions induce c-Myc promoter activity in Beas-2B cells.

Figure 3.

(A) Nickel ions increased c-Myc mRNA level in Beas-2B cells. The cells were treated with NiSO4 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h. After treatment, RNA was isolated for RT-PCR. The bold numbers inserted between the blots are the densitometric data normalized to β-actin as fold-control. (B) Nickel ions failed to increase c-Myc mRNA stability in Beas-2B cells. Beas-2B cells were treated with NiSO4 at indicated concentrations for 16 h, and then Actinomycin D (ActD) was added to a final concentration of 2μg/ml. Cells were then lysed at selected time intervals and RNA was isolated for RT-PCR. The densitometric data normalized to β-actin was inserted between the blots as fold-control and used to fit the exponential lines by Excel, and half-lives were calculated and shown below the blots. (C) Nickel ions induced c-Myc promoter activity in Beas-2B cells. Beas-2B cells were transfected with 100 ng of c-Myc promoter construct along with 5 ng of Renilla luciferase construct (RL-TK), and incubated with increased levels of soluble nickel for 40 h. The luciferase activity was measured in total cell lysates and normalized to Renilla activity as an internal control. The relative luciferase activities are shown as mean value (plus standard errors) obtained from three independent experiments.

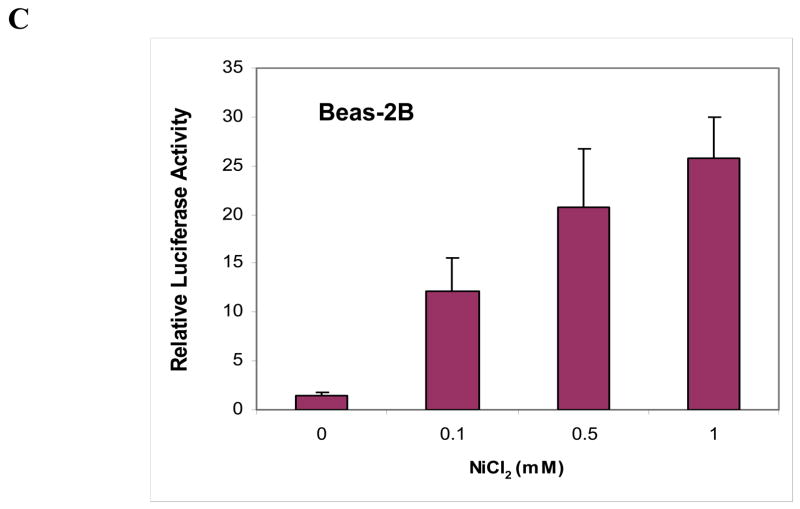

The stability of c-Myc protein was not increased by nickel ions in Beas-2B cells

Since nickel ions induced c-Myc protein as well as mRNA transcription in Beas-2B cells, we investigated whether nickel ions impacted the stability of c-Myc protein. The stability of c-Myc protein was assessed by using the translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX). Fig. 4 illustrated that nickel ions exposure did not augment the stability of c-Myc protein in Beas-2B cells, which also was confirmed by using a pulse-chase approach after the cellular c-Myc was radiolabelled with 35S-methioninein (Yeh et al., 2004) (data not shown), suggesting that nickel ions increased the levels of c-Myc protein primarily by stimulating its transcription.

Figure 4.

Nickel ions failed to alter c-Myc protein stability in Beas-2B cells. (Beas-2B cells were treated with 0.5mM NiSO4 for 24 h and then cycloheximide (CHX) was added to a final concentration of 10μg/ml to block cellular protein translation. The cells were then lysed using RIPA buffer at selected time intervals, whole cell lysate was isolated for western blot. The same membrane was stripped and re-probed with α-tubulin antibody as loading control. Similar data were obtained in at least two other independent experiments, and only one representative blot is shown here. The bold numbers inserted between the blots are the densitometric data normalized to α-tubulin as fold-control.

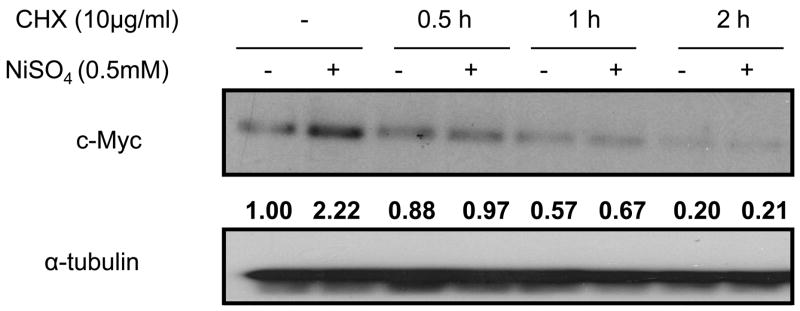

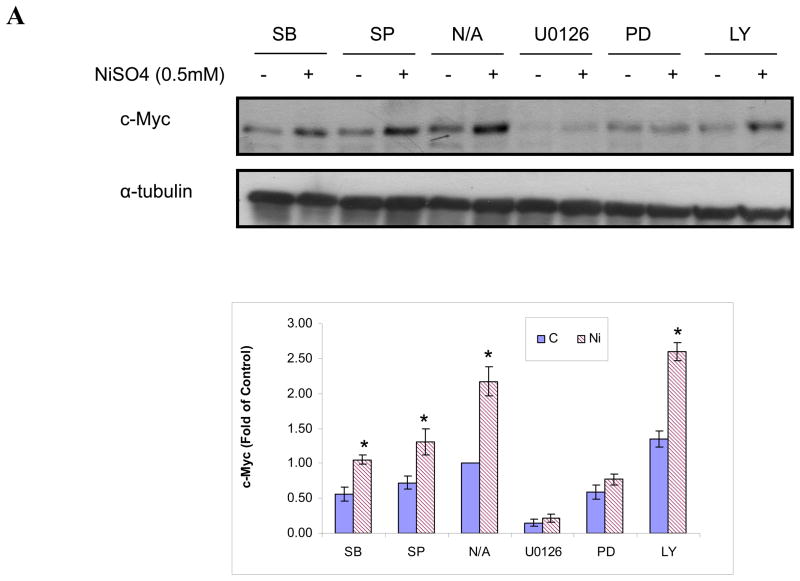

Nickel ions induced c-Myc in Beas-2B cells by the Ras/ERK pathway

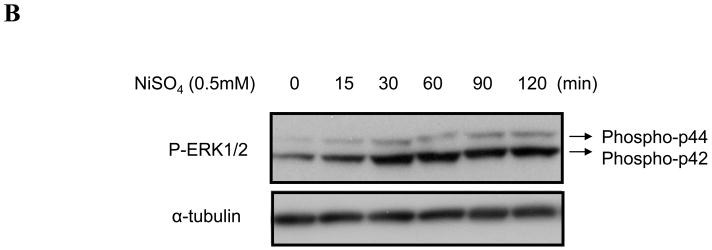

In Beas-2B cells c-Myc protein was increased by nickel ions through an enhancement of c-Myc transcriptional activity. There exist multiple signaling pathways that control c-Myc transcription. Previous studies have demonstrated that nickel compounds activated a distinct set of signaling pathways in human lung cells including NF-κB (Ding et al., 2006), Ras/ERK (Tessier and Pascal, 2006) and Ras/JNK (Ke et al., 2008). Various inhibitors of these pathways were used to determine which of these impacted upon the activation of c-Myc transcription. Beas-2B cells were treated with selected inhibitors for 1 h prior to the time that cells were exposed to 0.5mM NiSO4 for an additional 24 h. The results showed that both MEK and ERK inhibitors (U0126 and PD98059) attenuated nickel ion-induced c-Myc protein. In contrast, pretreatment of Beas-2B cells with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (20μM), p38 inhibitor SB203580 (20μM), or JNK inhibitor SP600125 (1μM), respectively, had no effect on the c-Myc induction by nickel ions (Fig. 5A). In further support of the involvement of the ERK pathway, we observed that exposure of Beas-2B cells to NiSO4 (0.5 mM) increased the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 5B). Collectively, these results argue that nickel compounds induce c-Myc in Beas-2B cells through the MEK/ERK pathway.

Figure 5.

Nickel ions increased c-Myc in Beas-2B cells through MEK-ERK pathway. (A) Beas-2B cells were not treated (N/A) or treated with MEK inhibitor U0126 (20μM), ERK inhibitor PD98059 (20μM), PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (20μM), p38 inhibitor SB203580 (20μM), or JNK inhibitor SP600125 (1μM) for 1 h, and then with 0.5mM NiSO4 for 24 h. The cells were then lyzed and subjected to Western blot analyzing. The upper panel is a representative blot while the lower panel is the densitometric data normalized to α-tubulin given as fold-control using two tailed Student’s T-test. Data are expressed as mean + SE, obtained from three independent experiments. * Statistically significantly change (P < 0.05) when compared to samples without nickel treatment. (B) Beas-2B cells were treated with 0.5mM NiSO4 for indicated time. The cells were then lysed and Western blots were conducted using antibodies against c-Myc, phosphorylated ERK (PERK), and α-tubulin. Similar data were obtained in at least two other independent experiments, and only one representative blot is shown here.

Discussion

To study the possible role of c-Myc in nickel compounds-induced toxicity and carcinogenesis, we investigated the effects of nickel compounds on c-Myc in immortalized but not tumorigenic human bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells, and studied the mechanisms by which nickel compounds induced c-Myc dysregulation. The Beas-2B cell line was derived from normal human bronchial epithelium from non-cancerous individuals and immortalized via adenovirus 12-SV40 transformation. Since the lung epithelium is an important barrier for protecting respiratory tract from toxic irrespirable particulates, and inhalation is the primary route for human exposure to nickel compounds, the Beas-2B cell line is a good model to study the toxic and carcinogenic effects of nickel ions. It has been shown that exposure to 2.34 μg/cm2 nickel subsulfide did not inhibit the ability of Beas-2B cells to divide and form colonies (Andrew and Barchowsky, 2000). Last year, a study in our laboratory demonstrated that NiCl2 at 0.5 and 1 mM was approximately equatoxic with Ni3S2 at 0.5 and 1.0 μg/cm2, respectively, when the cells were treated for 24 hrs or 48 hrs (Ke et al., 2007). Moreover, 1 mM NiCl2 and 0.5 mM NiSO4 have been used in Beas-2B in previous studies (Huang et al., 2002; Ding et al., 2006). Therefore, the nickel ion exposure of Beas-2B cells in this study was performed at a maximal concentration of 1 mM.

Previous studies have shown that c-Myc is maintained at high levels in tumorigenic cells (Hann and Eisenman, 1984) and at low level in normal proliferating cells (Rudolph et al., 1999). We observed that c-Myc protein level was increased by nickel ions in the non-tumorigenic cell lines (Beas-2B and HaCat cells). Furthermore, we found that nickel ions induced apoptosis in Beas-2B cells, and the observed apoptosis was mediated by c-Myc (Fig. 2A and 2B). However, the apoptotic effect was dose dependent. As shown in Fig. 2A, the significant induction of apoptosis is in the treatment group with 0.5 mM and 1.0 mM of NiSO4 but not at the dose of 0.25 mM. Another study also showed that 0.5 mM NiCl2 induced apoptosis in Beas-2B cells (Ding et al., 2006). Therefore, exposures to 0.5 mM or higher doses of nickel compounds triggered cell apoptosis mediated by the induction of higher c-Myc protein levels.

Several pathways have been implicated in c-Myc induced apoptosis. First, c-Myc induces the expression of p19ARF, which stabilizes p53 (Gregory et al., 2005). Second, c-Myc induces the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein BIM (Jiang et al., 2007). Third, c-Myc blocks the expression of the anti-apoptotic factors BCL2 and BCL-XL, which both lead to the release of cytochrome c in a p53-independent manner (Chiarugi and Ruggiero, 1996; Juin et al., 1999; Greider et al., 2002). Another potential mechanism of c-Myc-induced apoptosis is the ability to cause DNA damage (DNA double strand breaks (DSBs)) and to block DNA-damage dependent cell-cycle arrest (Vafa et al., 2002). It was previously shown that the SV40 T antigen immortalized cell line Beas-2B had a mutation at codon 47 of p53 (CCG → TCG) causing an amino acid change from Pro to Ser (Lehman et al., 1993), suggesting that c-Myc mediated apoptosis in Beas-2B is through a p53-independent manner. Previous studies also found that nickel (II) caused a slight increase in DNA strand breaks at 250 μM and higher dose in mammalian cells (Dally and Hartwig, 1997), and recent study in the human T cell line jurkat reported that the apoptotic cell death induced by nickel (II) was mediated by the suppression of BCL2 (Guan et al., 2007), indicating that nickel-induced apoptosis in Beas-2B cells is likely via an increase of DNA strand breaks or a reduction of bcl-2 expression by c-Myc activation.

As mentioned above, 250 μM of NiSO4 significantly increased c-Myc protein levels (Fig. 1B) but did not induce much apoptosis (Fig. 2A) in Beas-2B cells. These results indicate that a lower dose of nickel does not induce the level of c-Myc enough to trigger cell apoptosis in Beas-2B cells. Apoptosis plays an important role as a protective mechanism against neoplastic development in the organism by eliminating genetically damaged cells. Resistance towards apoptosis is a key factor for the survival of a malignant cell. It has been shown that a dose of nickel below 200μM promotes cell proliferation instead of apoptosis in SAEC cells (Tessier and Pascal, 2006). Additionally, we observed that exposure of Beas-2B cells to a lower dose of NiCl2 (100 μM) for 7 to 12 weeks resulted in an increased number of anchorage-independent colonies in soft agar compared to untreated Beas-2B cells, indicating that lower doses of nickel ions are capable of transforming Beas-2B cells (data not shown). Therefore, c-Myc induced by lower doses of nickel ions may promote Beas-2B cells to different cell fates, such as cell transformation. Further studies should be directed at determining whether c-Myc is involved in nickel-induced cell transformation in Beas-2B cells and if this contributes to nickel-mediated carcinogenesis.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that epigenetic events are likely involved in nickel carcinogenesis (Chen et al., 2006; Ke et al., 2006; Ke et al., 2008). Our new finding shows that nickel ions increased tri-methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 in Beas-2B cells (Zhou et al. Submitted to Carcinogenesis), while previous studies have reported that the JARID1 family class of demethylase enzyme which catalyze the removal of methyl groups from histone H3 lysine 4 can be suppressed by c-Myc binding (Secombe and Eisenman, 2007). This current study shows that nickel ions induce c-Myc protein and suggests that this c-Myc induction may play a function in nickel-induced chromatin remodeling and epigenetic effects.

c-Myc protein level is tightly controlled on multiple levels, including transcription initiation and elongation, translation, and the stability of mRNA and protein. In order to dissect the mechanisms of nickel-induced c-Myc protein level, we investigated the effects of nickel ions on c-Myc mRNA level, c-Myc promoter activity, and stability of mRNA and protein. The results show that 100 μM or higher doses of Ni(II) induced more than 10-fold of c-Myc promoter activity, but did not significantly increase the stability of mRNA and protein, indicating nickel-increased c-Myc protein level is through induction of c-Myc transcription.

To further study the possible mechanism by which nickel induced c-Myc promoter activity, various inhibitors of different suspicious signaling pathways were utilized to determine which pathway may be involved in nickel-induced c-Myc. Our data demonstrated that only the ERK pathway was involved in nickel-induced c-Myc transcription, but not the other MAP kinase family members, such as p38, PI3K or JNK pathway. Nickel sulfide was shown to induce activation of MAP kinase signaling (Govindarajan, B., et al., 2002), and to do so through its induction of oxidative stress. Nickel compounds generate intracellular oxidants after several hours of exposure in cells, as detected by the dichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescent assay method or by electron spin (ES) resonance (Huang, C., et al., 1993; Huang, C., et al., 2001). It was suggested that Ni-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) play an important role in the activation of signaling pathways such as MAPKs.

In summary, we report here that c-Myc protein level is increased by nickel ions in immortalized but non-tumorigenic Beas-2B and HaCat cells; and the nickel-induced apoptosis in Beas-2B cells is dependent on the induction of c-Myc. We also demonstrated that in Beas-2B cells the increased levels of c-Myc protein induced by nickel ions exposure is mediated by inducing c-Myc transcription via the Ras/ERK pathway. This study was the first to introduce c-Myc into metal toxicity and carcinogenesis and has connected many possible functions of c-Myc in nickel-induced toxicity and carcinogenesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. John M. Sedivy from Brown University for providing us with TGR-1, HO15.19 and HOmyc3 cell lines used in this study. This work was supported by grants ES00260, ES014454, ES005512, ES010344, and T32-ES07324 from the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences, and grant CA16087 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmed NN, Grimes HL, Bellacosa A, Chan TO, Tsichlis PN. Transduction of interleukin-2 antiapoptotic and proliferative signals via Akt protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3627–3632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew A, Barchowsky A. Nickel-induced plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression inhibits the fibrinolytic activity of human airway epithelial cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;168:50–57. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomeusz G, Talpaz M, Bornmann W, Kong LY, Donato NJ. Degrasyn activates proteasomal-dependent degradation of c-Myc. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3912–3918. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez Y, Yang H, Cheng JQ, Kruk PA. Pyk2/ERK 1/2 mediate Sp1- and c-Myc-dependent induction of telomerase activity by epidermal growth factor. Growth Factors. 2008;26:1–11. doi: 10.1080/08977190802001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann KA, Landolph JR. Induction of anchorage independence in human diploid foreskin fibroblasts by carcinogenic metal salts. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3815–3823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggart NW, Costa M. Assessment of the uptake and mutagenicity of nickel chloride in salmonella tester strains. Mutat Res. 1986;175:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(86)90056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Ke Q, Kluz T, Yan Y, Costa M. Nickel ions increase histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation and induce transgene silencing. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3728–3737. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3728-3737.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarugi V, Ruggiero M. Role of three cancer “master genes” p53, bcl2 and c-myc on the apoptotic process. Tumori. 1996;82:205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dally H, Hartwig A. Induction and repair inhibition of oxidative DNA damage by nickel(II) and cadmium(II) in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1021–1026. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.5.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani C, Blanchard JM, Piechaczyk M, El Sabouty S, Marty L, Jeanteur P. Extreme instability of myc mRNA in normal and transformed human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:7046–7050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Zhang X, Li J, Song L, Ouyang W, Zhang D, Xue C, Costa M, Melendez JA, Huang C. Nickel compounds render anti-apoptotic effect to human bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells by induction of cyclooxygenase-2 through an IKKbeta/p65-dependent and IKKalpha- and p50-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39022–39032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604798200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R, Morgan LG, Speizer FE. Cancers of the lung and nasal sinuses in nickel workers. Br J Cancer. 1970;24:623–632. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1970.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge R, Wang W, Kramer PM, Yang S, Tao L, Pereira MA. Wy-14,643-induced hypomethylation of the c-myc gene in mouse liver. Toxicol Sci. 2001;62:28–35. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/62.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P. Human exposure to nickel. IARC Sci Publ. 1984:469–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory MA, Qi Y, Hann SR. The ARF tumor suppressor: keeping Myc on a leash. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:249–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider C, Chattopadhyay A, Parkhurst C, Yang E. BCL-x(L) and BCL2 delay Myc-induced cell cycle entry through elevation of p27 and inhibition of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Oncogene. 2002;21:7765–7775. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan F, Zhang D, Wang X, Chen J. Nitric oxide and bcl-2 mediated the apoptosis induced by nickel(II) in human T hybridoma cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;221:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann SR. Regulation and function of non-AUG-initiated proto-oncogenes. Biochimie. 1994;76:880–886. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann SR. Role of post-translational modifications in regulating c-Myc proteolysis, transcriptional activity and biological function. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:288–302. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann SR, Eisenman RN. Proteins encoded by the human c-myc oncogene: differential expression in neoplastic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:2486–2497. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.11.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann SR, King MW, Bentley DL, Anderson CW, Eisenman RN. A non-AUG translational initiation in c-myc exon 1 generates an N-terminally distinct protein whose synthesis is disrupted in Burkitt’s lymphomas. Cell. 1988;52:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann SR, Thompson CB, Eisenman RN. c-myc oncogene protein synthesis is independent of the cell cycle in human and avian cells. Nature. 1985;314:366–369. doi: 10.1038/314366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Davidson G, Li J, Yan Y, Chen F, Costa M, Chen LC, Huang C. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB and not activator protein-1 in cellular response to nickel compounds. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 5):835–839. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Tsang YH, Yu Q. c-Myc overexpression sensitizes Bim-mediated Bax activation for apoptosis induced by histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) through regulating Bcl-2/Bcl-xL expression. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1016–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juin P, Hueber AO, Littlewood T, Evan G. c-Myc-induced sensitization to apoptosis is mediated through cytochrome c release. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1367–1381. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Q, Davidson T, Chen H, Kluz T, Costa M. Alterations of histone modifications and transgene silencing by nickel chloride. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1481–1488. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Q, Davidson T, Kluz T, Oller A, Costa M. Fluorescent tracking of nickel ions in human cultured cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;219:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Q, Li Q, Ellen TP, Sun H, Costa M. Nickel compounds induce phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 by activating JNK-MAPK pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2008 doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerckaert GA, LeBoeuf RA, Isfort RJ. Use of the Syrian hamster embryo cell transformation assay for determining the carcinogenic potential of heavy metal compounds. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1996;34:67–72. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper CF, Woutersen RA, Slootweg PJ, Feron VJ. Carcinogenic response of the nasal cavity to inhaled chemical mixtures. Mutat Res. 1997;380:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TC, Ziff EB. Mxi1 is a repressor of the c-Myc promoter and reverses activation by USF. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:595–606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YW, Broday L, Costa M. Effects of nickel on DNA methyltransferase activity and genomic DNA methylation levels. Mutat Res. 1998;415:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(98)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YW, Klein CB, Kargacin B, Salnikow K, Kitahara J, Dowjat K, Zhitkovich A, Christie NT, Costa M. Carcinogenic nickel silences gene expression by chromatin condensation and DNA methylation: a new model for epigenetic carcinogens. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2547–2557. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman TA, Modali R, Boukamp P, Stanek J, Bennett WP, Welsh JA, Metcalf RA, Stampfer MR, Fusenig N, Rogan EM, et al. p53 mutations in human immortalized epithelial cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:833–839. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher B, Larsson LG. The world according to MYC. Conference on MYC and the transcriptional control of proliferation and oncogenesis. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:1110–1114. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateyak MK, Obaya AJ, Sedivy JM. c-Myc regulates cyclin D-Cdk4 and -Cdk6 activity but affects cell cycle progression at multiple independent points. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4672–4683. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AC, Mog S, McKinney L, Luo L, Allen J, Xu J, Page N. Neoplastic transformation of human osteoblast cells to the tumorigenic phenotype by heavy metal-tungsten alloy particles: induction of genotoxic effects. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:115–125. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph C, Adam G, Simm A. Determination of copy number of c-Myc protein per cell by quantitative Western blotting. Anal Biochem. 1999;269:66–71. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom OJ, Meniel VS, Muncan V, Phesse TJ, Wilkins JA, Reed KR, Vass JK, Athineos D, Clevers H, Clarke AR. Myc deletion rescues Apc deficiency in the small intestine. Nature. 2007;446:676–679. doi: 10.1038/nature05674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears R, Leone G, DeGregori J, Nevins JR. Ras enhances Myc protein stability. Mol Cell. 1999;3:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secombe J, Eisenman RN. The function and regulation of the JARID1 family of histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases: the Myc connection. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1324–1328. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.11.4269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra J, Yoshida T, Joazeiro CA, Jones KA. The APC tumor suppressor counteracts beta-catenin activation and H3K4 methylation at Wnt target genes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:586–600. doi: 10.1101/gad.1385806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao L, Yang S, Xie M, Kramer PM, Pereira MA. Hypomethylation and overexpression of c-jun and c-myc protooncogenes and increased DNA methyltransferase activity in dichloroacetic and trichloroacetic acid-promoted mouse liver tumors. Cancer Lett. 2000;158:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub R, Kirsch I, Morton C, Lenoir G, Swan D, Tronick S, Aaronson S, Leder P. Translocation of the c-myc gene into the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus in human Burkitt lymphoma and murine plasmacytoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:7837–7841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier DM, Pascal LE. Activation of MAP kinases by hexavalent chromium, manganese and nickel in human lung epithelial cells. Toxicol Lett. 2006;167:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafa O, Wade M, Kern S, Beeche M, Pandita TK, Hampton GM, Wahl GM. c-Myc can induce DNA damage, increase reactive oxygen species, and mitigate p53 function: a mechanism for oncogene-induced genetic instability. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1031–1044. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CH, van Riggelen J, Yetil A, Fan AC, Bachireddy P, Felsher DW. Cellular senescence is an important mechanism of tumor regression upon c-Myc inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13028–13033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701953104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh E, Cunningham M, Arnold H, Chasse D, Monteith T, Ivaldi G, Hahn WC, Stukenberg PT, Shenolikar S, Uchida T, Counter CM, Nevins JR, Means AR, Sears R. A signalling pathway controlling c-Myc degradation that impacts oncogenic transformation of human cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:308–318. doi: 10.1038/ncb1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]