Abstract

The prion protein is a ubiquitous neuronal membrane protein. Misfolding of the prion protein has been implicated in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (prion diseases). It has been demonstrated that the human prion protein (PrP) is capable of coordinating at least five CuII ions under physiological conditions; four copper binding sites can be found in the octarepeat domain between residues 61 – 91, while another copper binding site can be found in the unstructured “amyloidogenic” domain between residues 91 – 126 (PrP(91–126). Herein we expand upon a previous study (J. Shearer, P. Soh, Inorg. Chem. 46 (2007) 710–719) where we demonstrated that the physiologically relevant high affinity CuII coordination site within PrP(91–126) is found between residues 106–114. It was shown that CuII is contained within a square planar (N/O)3S coordination environment with one His imidazole ligand (H(111)) and one Met thioether ligand (either M(109) or M(112)). The identity of the Met thioether ligand was not identified in that study. In this study we perform a detailed investigation of the CuII coordination environment within the PrP fragment containing residues 106–114 (PrP(106–114)) involving optical, X-ray absorption, EPR, and fluorescence spectroscopies in conjunction with electronic structure calculations. By using derivatives of PrP(106–114) with systematic Met → Ile “mutations” we show that the CuII coordination environment within PrP(106–114) is actually comprised of a mixture of two major species; one CuII(N/O)3S center with the M(109) thioether coordinated to CuII and another CuII(N/O)3S center with the M(112) thioether coordinated to CuII. Furthermore, deletion of one or more Met residues from the primary sequence of PrP(106–114) both reduces the CuII affinity of the peptide by two to seven fold, and renders the resulting CuII metallopeptides redox inactive. The biological implications of these findings are discussed.

Introduction

Neurological disorders caused by the aggregation of neuronal proteins represent some of the most dreaded human diseases as a diagnosis with such a disorder represents a certain death sentence following the slow loss of cognitive and physical abilities.[1] The most common of these disorders is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which strikes approximately 15% of all people who live past the age of 55.[2] Far less common are transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), or prion diseases, that strike less than one out of every one million people, and are caused by the aggregation of the prion protein.[3–8] Prion diseases can be found in many mammalian species ranging from humans to cattle to felines. In humans these diseases include: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, kuru, fatal familial insomnia, Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker disease, and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD).[2–10] It was vCJD that brought prion diseases to the public’s attention as it has been widely speculated that the cause for this disease is the ingestion of beef derived from cattle suffering from bovine spongiform encephalopathy (or “Mad Cow” disease).[10,11]

As the name implies TSEs are infectious diseases. Although much remains unknown about the exact mechanism of transmission, it has been proposed that exposure of the misfolded variant of the PrP (PrPSc) to its normally folded cellular isoform (PrPC) causes PrPC to misfold into PrPSc.[3–8] Unlike PrPC, PrPSc is highly insoluble and readily forms aggregates. These aggregates in turn produce neuronal plaques, which then induce neuron apoptosis. As the disease progresses holes form in the brain, which leads to impairment and the eventual death of the afflicted individual.

Similar to AD much remains unknown about the exact molecular cause of TSEs or the physiological function of the PrP. Although PrPs are ubiquitous neuronal membrane proteins their exact neurobiological role has not been elucidated. However, owing to their high affinity for CuII it has been speculated that they may be involved in copper homeostasis or transport.[12,13] It has been shown that the PrP is highly selective for copper ions over other biologically relevant metalions.[12,14,15] Furthermore the PrP can bind at least five CuII ions with resulting Kd values ranging from the high µM to low nM.[12,15–18] Considering the high affinity of the PrP towards CuII several recent studies have been reported examining the coordination environment of CuII within the PrP.

The PrP can be roughly divided into three (somewhat overlapping) domains.[12,15] The C-terminal domain (residues 120 – 261) is well structured with PrPC possessing a high α-helical content, and PrPSc comprised mostly of β-sheets.[19–22] This portion of the PrP likely contains no CuII binding sites. In contrast, the N-terminus is unstructured in solution and contains two separate CuII binding regions. The most widely studied CuII binding domain is the “octarepeat” domain, which is comprised of the octa-repeating sequence PHGGGWGQ found between residues 60 – 91.[12,15] Less thoroughly investigated is the second copper-binding region also contained within the N-terminus, which is comprised of residues 91–126 (PrP(91–126); QGGGTHSQWNKPSKPKTNMKHMAGAAAAGAVVGGLG).[12,13,15,17,23–26] This fragment has been dubbed the amyloidogenic or neurotoxic PrP fragment since it, as well as the N-unacylated fragment 106–126, is capable of inducing a prion disease when injected into transgenic mice.[27]

PrP(91–126) is capable of coordinating one or possibly two CuII ions.[13,15] It has been proposed that the imidazole derived from either H(96) or H(111) (or both) is utilized as a ligand for CuII. Although many structural and spectroscopic studies (including: EPR, ENDOR, EXAFS, UV-vis, and CD spectroscopies, along with speciation studies) have been performed on CuII derivatives from this region of the PrP the exact CuII coordination environment and ligating residues to copper within PrP(91–126) still remains unresolved.[13,15,17,27–29] In a recent study we provided evidence that the relevant copper coordinating domain is contained within PrP(106–114) (AcNH-KTNMKHMAG).[17] This peptide provides CuII with a coordination environment that reproduces the physical and structural properties of the CuII-adduct of the longer PrP fragment. From that study we demonstrated that CuII was contained in a square planar coordination geometry with one nitrogen donor from H(111), two additional non-imidazole N/O donors, and one thioether S-donor derived from a Met residue (Chart 1). Based on work by Di Natale et. al. at least one of these N/O donors is derived from a deprotonated amide N from the peptide backbone.[24] However, in our pervious study we did not determine which of the two Met residues (M(109) or M(112)) was involved in coordination to CuII. In this study we further probe the coordination environment of CuII within PrP(106–114) to unambiguously determine which Met thioether is utilized as a ligand to CuII. Using a variety of spectroscopic and structural techniques we will demonstrate that both M(109) and M(112) can be utilized as ligands to CuII at physiological pH.

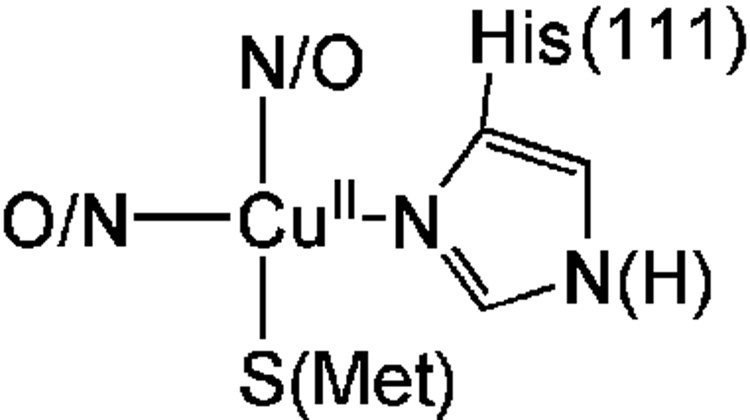

Chart 1.

Proposed structure of CuII within the amyloidogenic PrP fragment of the human prion protein based on an X-ray absorption spectroscopic analysis.

Experimental

Peptide Synthesis and Purification

All peptides used in this study were prepared and purified as previously described.[17] Analytical data for the newly prepared peptides used in this study are as follows:

AcN-KTNIKHMAG (PrP(106–114)(M109I))

Linear gradient 10–32 % MeCN (0.1% TFA) in H2O (0.1% TFA) over 35 min. Yield 67 % [Rt= 2.59 min]. Analytical rp-HPLC: 10–65 % MeCN (0.1% TFA) in H2O (0.1% TFA) over 65 min [Rt=8.90 min]. ESI-MS (M+) observed m/z 1041.40 calc: 1041.27.

AcN-KTNMKHIAG (PrP(106–114)(M112I))

Linear gradient 10–32 % MeCN (0.1% TFA) in H2O (0.1% TFA) over 35 min. Yield 50 % [Rt= 2.88 min]. Analytical rp-HPLC: 10–65 % MeCN (0.1% TFA) in H2O (0.1% TFA) over 65 min [Rt= 8.00 min]. ESI-MS (M+) observed m/z 1041.47 calc: 1041.27.

AcN-KTNIKHIAG (PrP(106–114)(M109/112I))

Linear gradient 10–32 % MeCN (0.1% TFA) in H2O (0.1% TFA) over 35 min. Yield 60 % [Rt= 3.04 min]. Analytical rp-HPLC: 10–65 % MeCN (0.1% TFA) in H2O (0.1% TFA) over 65 min [Rt= 5.03 min]. ESI-MS (M+) observed m/z 1059.31 calc: 1058.27.

Physical Methods

Electronic absorption studies were performed on a Varian CARY 50 UV-vis spectrophotometer using 1 cm quartz cuvettes. Peptide concentrations were determined by estimating a water content of ~20% weight by weight of the lyophilized peptide (based on previous work). All peptide solutions were made using a 50 mM NEM solution buffered to pH = 7.4. CuII was added to the peptide solutions from a freshly prepared solution of CuCl2•2H2O (pH ~ 6.0). The CuII solution was fairly concentrated and thus the small quantity of CuII solution added did not have any measurable influence on the pH of the peptide solution. CD spectra were obtained on an OLIS DSM-17 spectropolarimeter using 1 cm quartz cuvettes.

EPR spectra were obtained on a Bruker EMX 6/1 EPR spectrometer with a microwave frequency meter and an Oxford Instruments ESR900 liquid He cryostat system. Samples were measured as frozen glasses (1:1 buffer:glycerol (buffer = 50 mM NEM (pH 7.4))) at 20 K in quartz EPR tubes. Final metallopeptide concentrations were 0.05 mM. All spectra represent the average of 8 scans with 1024 points per spectrum. The data collection parameters were set as follows: center field = 3100 G; sweep width = 1000 G; microwave power = 0.5 mW; modulation amplitude 10 G; modulation frequency = 100 kHz; receiver gain = 5.02 × 104; time constant = 40.96 ms; conversion time = 40.96 ms. EPR spectra were subsequently simulated using Simpip.[30]

The electrochemical data were obtained using methods previously described.[17] To increase the electrochemical response of the metallopeptides, all electrochemical measurements were made using immobilized peptide thin films on the electrode surface. The peptide films were prepared using the procedure of Rusling[31] as was previously described.[17]

X-ray absorption data were collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratories; Upton, NY) on beamline X3b (ring operating conditions: 2.8 GeV; 200 – 305 mA). Freshly prepared solutions of CuCl2•2H2O in 50 mM NEM (pH 6.0) were added to solutions of the peptides in 1:1 buffer:glycerol (buffer = 50 mM NEM (pH 7.4)). Final peptide:CuII ratios were 1:0.95 to ensure that no free CuII was observed in the spectra. The copper-containing peptide solutions were then injected into aluminum sample holders in between two windows made of Kapton tape (3M, cat. #1205; Minneapolis, MN) and frozen in liquid nitrogen forming a glass. Energy selection was accomplished by using a Si(111) double monochromator. Energy calibrations were performed by recording a reference spectrum of Cu foil (first inflection point assigned to 8980.3 eV) simultaneously with the samples. All samples were maintained at 20 K throughout the data collection using a helium Displex cryostat unless otherwise noted. The spectra are reported as fluorescence data, which were recorded utilizing a 13-element Ge solid-state fluorescence detector (Canberra). Total count rates were maintained under 30 kHz per channel, and a deadtime correction of 3 µs was utilized (this had a negligible influence on the data). Data were obtained in 5.0 eV steps in the pre-edge region (8779 – 8958 eV), 0.3 eV steps in the edge region (8959 – 9023 eV), 2.0 eV steps in the near-edge region (9024 – 9278 eV), and 5.0 eV steps in the far-edge region (9279 eV – 13.5 k). All spectra represent the averaged sum of at least 9 to as many as 15 spectra. Data analysis was performed using the XAS analysis package EXAFS123[32] and FEFF 8.4[33] as previously described.[17]

Determination of CuII Stability for {CuII(PrP(106–114)(M109I))}, {CuII(PrP(106–114(M112I))}, and {CuII(PrP(106–114(M109/112I))}

Stability constants for the metallopeptides were determined by fluorometry on a Horiba Fluoromax-3 flourometer at pH = 7.4 (50 mM NEM). We monitored the quenching of the W(99) emission in PrP(91–126) at 350 nm following excitation at a wavelength of 285 nm. To determine the stability constant for {CuII(PrP(106–114)(MnnnI))} (where nnn = 109, 112, or 109/112) a 10 µM solution of {CuII(PrP(91–126))} was prepared (pH 7.4) and the appropriate PrP(106–114)(MnnnI) fragment was titrated into solution. The fluorescence intensity of the W emission at 350 nm for {CuII(PrP(91–126))} is 62% that of free PrP(91–126).[17] As the PrP fragment removes CuII from PrP(91–126) the W fluorescence increases in intensity until it reaches the intensity of free PrP(91–126). Concentration for all species present were then extracted from the titration plot by a non-linear least-squares fitting routine with Kd as the fitted variable. The dissociation constant (Kd) for {CuII(PrP(106–114)(M(nnn)I))} can be calculated according to:

| (1) |

where:

| (2) |

and Kd* is the CuII dissociation constant for {CuII(PrP(91–126))} (92(8) × 10−6).[17]

Electronic Structure, Excited State, and EPR Calculations

All electronic structure and excited state calculations were performed using the Amsterdam Density Functional package version 2005.01 (ADF 2005.01)[34] or ORCA 2.6.35.[35] Geometry optimizations on all models were performed using the local density approximation of Vosko, Wilk, and Nussair and the non-local gradient corrections of Beck and Perdew.[36–41] For all calculations using ADF 2005.01 the frozen core approximation was used for the 1s orbital of all second row elements, and the 1s, 2s, and 2p orbitals for Cu and S. All valance orbitals were treated using a triple-ζ basis set with double polarization functions (ADF’s TZDP basis set). Time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculations were performed on all geometry optimized structures within ADF 2005.01. All excited state calculations utilized the conductor-like screening model (COSMO) to simulate solvation of the metallopeptide (ε = 78.9; r = 1.3 Å) [42,43] and the Van Leeuwen and Baerends exchange and correlation functional.[44] The first 30 lowest energy spin-allowed transition were calculated by TD-DFT methods. EPR g-values and Cu hyperfine coupling constants were calculated within ORCA by solving the coupled-perturbed SCF (CP-SCF) equations.[45] These calculations employed Becke’s three parameter hybrid functional for exchange with the Lee-Yang-Parr functional for correlation (B3LYP).[46–48] Ahlrichs’ triple ζ basis set with two sets of polarization functions were used for all atoms (Alrhich and coworker, unpublished results).[49]

Results and Discussion

In our previous study probing the metal coordination environment of CuII within PrP(91–126) we proposed that the high affinity coordination environment involved the imidazole from H(111), an amide nitrogen, an unidentified N/O donor, and a Met sulfur ligand.[17] This was on the basis of CD and X-ray absorption studies probing the CuII adducts of PrP(91–126) ({CuII(PrP(91–126))}) and PrP(106–114) ({CuII(PrP(106–114))}). The identity of the Met sulfur was not unambiguously assigned, however, and could be derived from either M(109) or M(112).

To identify which Met residue is donating the sulfur ligand to CuII in {CuII(PrP(106–114))} we prepared three derivatives of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} where the Met residues were replaced with Ile residues. These include: {CuII(PrP(106–114)(M109I)))} (Cu(M109I); PrP(106–114)(M109I)): AcN-KTNIKHMAG), {CuII(PrP(106–114)(M112I)))} (Cu(M112I); PrP(106–114)(M112I)): AcN-KTNMKHIAG), and {CuII(PrP(106–114)(M109/112I)))} (Cu(M109/112I) PrP(106–114)(M109/112I)): AcN-KTNIKHIA). The Met → Ile “mutation” was chosen as Ile is similar in size and charge to Met. Therefore Ile will not impose drastically different structural constraints about the CuII ion, but will still remove a potential ligand to CuII.

UV-vis and CD Spectra of {CuII(PrP(106–114(M(nnn)I)))}

The UV-vis spectra of the CuII adducts of the Met → Ile derivatives of PrP(106–114) are all similar in the low-energy ligand-field region; they all display a weak (ε ~ 120 M−1 cm−1) ligand-field band at ~610 nm (Table 1). Weak ligand-field transitions at ~610 nm are consistent with square planar CuII, and are similar to what was previously observed for {CuII(PrP(106 – 114))} (λmax = 604 nm; ε = 124 M−1 cm−1). In fact, the only major difference in the UV-vis spectrum between the three metallopeptides is that Cu(M109/112I) displays a slightly weaker ligand-field transition (ε = 117(5) M−1 cm−1) than the other two metallopeptides containing Met residues (Cu(M109I) = 131(4) M−1 cm−1; Cu(M112I) = 128(4) M−1 cm−1; Table 1). Unlike the UV-vis spectra, which did not prove very useful for determining if subtle differences exist in the coordination environment about the CuII center, CD measurements in the ligand-field region do display readily observable differences for the three metallopeptides (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

UV-vis, CD, CuII dissociation constants, and electrochemical data for {CuII(PrP(106–114))}, Cu(M109I), Cu(M112I), and Cu(M109/112I).

| Kd (µM) | Electronic Absorption | CD | Epa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ (nm) (ε(M−1 cm−1)) | λ (nm) | V (Ag/AgCl) | ||

| (Δε (M−1 cm−1)) | ||||

| {CuII(PrP(106–114)}b | 86(10) | 604 (124) | 644 (0.30) | −0.33d |

| 529 (95)c | 564 (0.14) | |||

| 350 (2 200)c | 484 (−0.19) | |||

| 296 (4 710) | 377 (−0.17) | |||

| 388 (0.04) | ||||

| 324 (1.53) | ||||

| Cu(M109I) | 350(55) | 611 (131) | 648 (0.31) | −0.7 |

| 351 (2 100)c | 536 (0.13) | |||

| 326 (4 700) | 476 (−0.11) | |||

| 328 (0.56) | ||||

| Cu(M112I) | 210(30) | 613 (128) | 652 (0.31) | −0.7 |

| 342 (2 800)c | 540 (0.19) | |||

| 322 (5 200) | 481 (−0.30) | |||

| 376 (−0.39) | ||||

| 332 (3.56) | ||||

| Cu(M109/112I) | 560(40) | 610 (117) | 668 (0.17) | −0.7 |

| 280 (29 000)c | 577 (−0.05) | |||

| 522 (0.19) | ||||

| 448 (−0.01) | ||||

| 372 (−0.34) | ||||

Approximate peak position of the reduction wave.

The data for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} are from reference 17.

sh: shoulder, and the subsequent ε at the energy indicated.

This is for the redox potential of {CuII(PrP(106–114))}, not the position of the irreversible reduction wave.

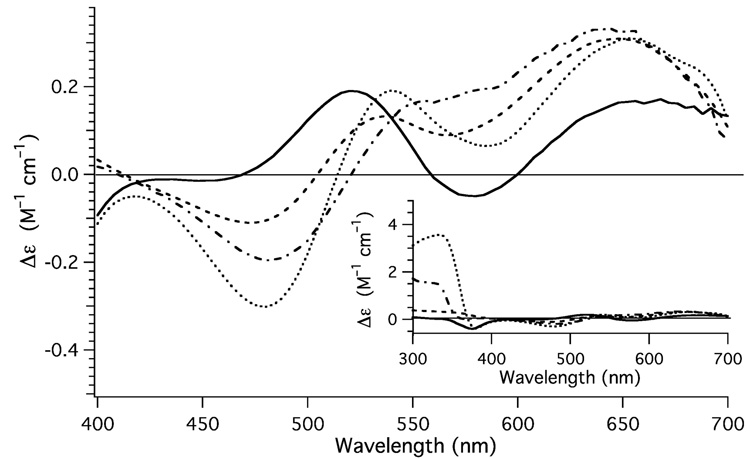

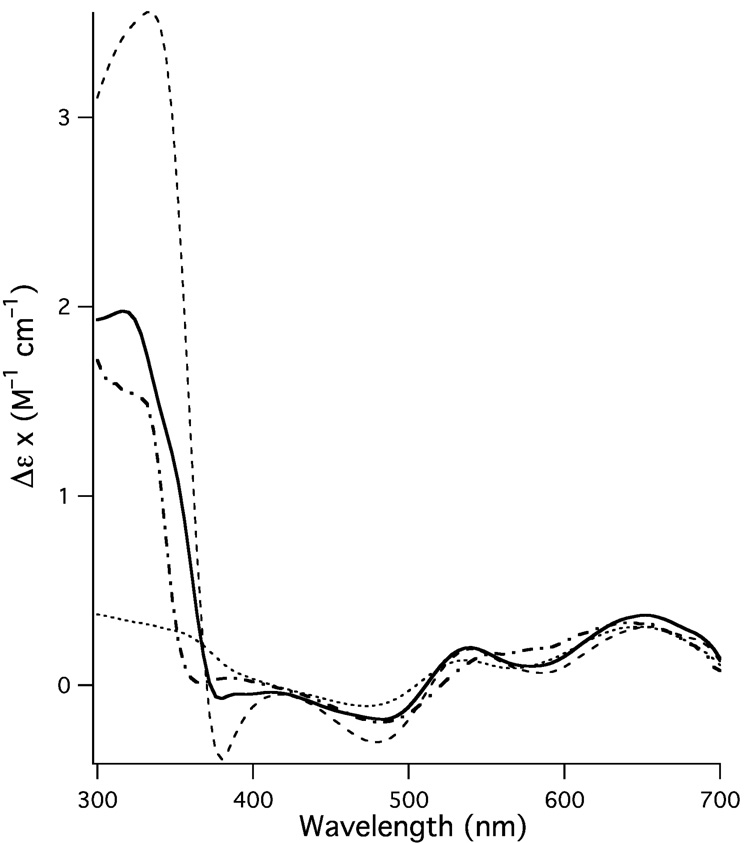

Fig. 1.

CD spectra obtained for Cu(M112I) (dotted spectrum), Cu(M109I) (dashed spectrum), and Cu(M109/112I) (solid spectrum) highlighting the ligand field. For comparison the CD spectrum of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} has been included (dotted and dashed spectrum). Inset: Depicts and expanded view of the CD spectrum Cu(M112I) (dotted spectrum), Cu(M109I) (dashed spectrum), Cu(M109/112I) (solid spectrum), and {CuII(PrP(106–114))} (dotted and dashed spectrum).

As can be seen the three metallopeptides all display difference in the intensity, position, and sign of the bands in the CD spectra. Previous studies[17,24] have shown that {CuII(PrP(106–114))} has a weak positive signed transition in the low-energy region of the CD spectrum, followed by two negative signed feature at slightly higher energy, and a positive signed high energy feature (Fig. 1, Table1). A comparison of {CuII(PrP(106–114)(M(nnn)I))} with {CuII(PrP(106–114))} demonstrates that although there are similarities in the CD spectra of the four metallopeptides (Fig. 1, Table 1), none of the derivatives of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} are a good match for the CD spectrum of the parent metallopeptide.

All of the peptides contain two positive signed low energy transitions at ~640 and ~550 nm. Furthermore, two of the three metallopeptides, Cu(M112I), and Cu(M109/112I), posses a weak negative signed feature in the CD spectrum at ~375 nm, while Cu(M109I) posses a weak positive signed feature at this energy. The corresponding negative signed feature in {CuII(PrP(106–114))} (377 nm, −0.16 M−1 cm−1) was previously assigned by us[17] and others[24] as the SMet → CuII ligand to metal charge transfer (LMCT) band. It is obvious that this cannot be due to the SMet → CuII LMCT band as Cu(M109/112I) does not contain a Met residue. At lower energy (~330 nm), the three Met containing metallopeptides {CuII(PrP(106–114))}, Cu(M109I), and Cu(M112I) each contain a positive signed feature in the CD spectrum. This transition is completely lacking in the CD spectrum of Cu(M109/112I). As will be shown in the section dealing with the time dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations of model CuII–peptides this feature in the CD spectra of the three Met containing metallopeptides is consistent with the SMet → CuII LMCT band.

Copper Binding Constants to {CuII(PrP(106–114)(M(nnn)I))} Measured Through Fluorometry

In a previous study we measured the CuII dissociation constant (Kd) from {CuII(PrP(106–114))} using fluorometry, and determined it has a Kd = 86(10) µM.[17] In that study the longer prion protein fragment PrP(91–126) was used as a competitive ligand for CuII. When CuII coordinates to PrP(91–126), forming {CuII(PrP(91–126))}, the intensity of the emission from W(99) in PrP(91–126) (following excitation at 285 nm) is quenched to 62% of its intensity in the free peptide. Thus, PrP(91–126) could be used to determine the CuII binding constants for other metallopeptides with similar Kd values ({CuII(PrP(91–126))} has a Kd = 98(2) µM[17]). In this study identical methods for determining Kd for the {CuII(PrP(106–114)(M(nnn)I))} derivatives were employed. Briefly, a 10 µM solution of {CuII(PrP(91–126))} was prepared and PrP(106–114)(M(nnn)I) was titrated into solution. The fluorescence intensity as a function of PrP(106–114)(M(nnn)I) concentration was then used to extract the {CuII(PrP(106–114)(M(nnn)I))} Kd values according to equations 1 and 2 (Fig. 2).

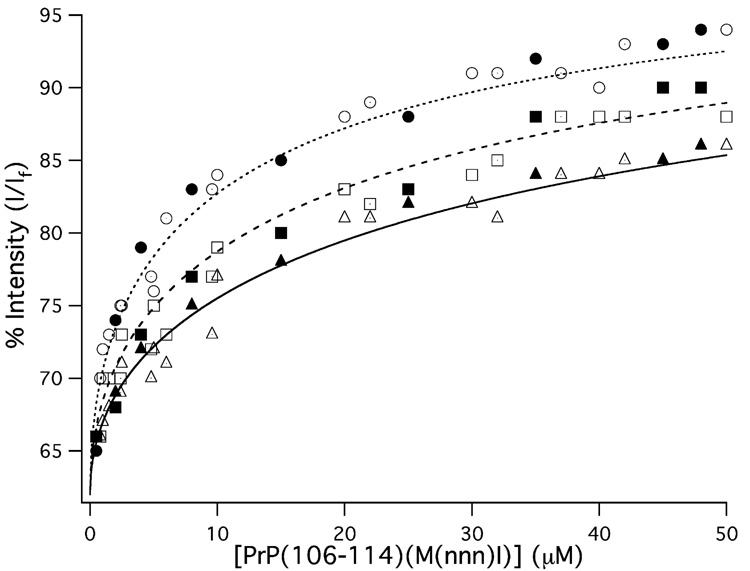

Fig. 2.

Fluorescence intensity of the 350 nm W(99) emission from PrP(91–126) as a function of PrP(106–114)(M(nnn)I) concentration. The titration data for PrP(106–114)(Cu(M112I)) are given as circles, the data for PrP(106–114)(Cu(M109I)) are given as squares, and the data for PrP(106–114)(Cu(M109/112I)) are given as triangles. The closed, open, and dotted shapes depict individual trials. The lines (dotted: PrP(106–114)(Cu(M112I)); dashed: PrP(106–114)(Cu(M109I)); solid: PrP(106–114)(Cu(M109/112I))) depict the best fits to the titration data.

As can be seen all three metallopeptides have similar affinities for CuII, however, differences in CuII affinities do exist. We find that all three Met → Ile derivatives of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} display reduced CuII affinity when compared to both the parent metallopeptide and the longer {CuII(PrP(91–126))} prion fragment. When both Met(109) and Met(112) are deleted from the peptide sequence, the resulting metallopeptide displays the weakest CuII affinity of the three metallopeptides investigated; Cu(M109/112I) displays a Kd = 560(40) µM, which is approximately seven times larger than the Kd measured for {CuII(PrP(106–114))}. Both Cu(M109I) and Cu(M112I) display higher CuII affinities than Cu(M109/112I), with measured Kd values of 350(55) and 210(30) µM, respectively. Nonetheless, these values are still two to three times larger than the Kd values measured for the parent metallopeptide. These data suggest that incorporation of both Met residues into PrP(106–114) enhance CuII coordination. Furthermore, these data also demonstrate that the incorporation of at least one Met residue will increase the affinity of the peptide towards CuII.

Copper K-edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

As is typical for most metallopeptides, {CuII(PrP(106–114))} and its derivatives will not readily crystallize to produce X-ray quality crystals. Therefore Cu K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy was utilized to obtain structural information on the Met → Ile derivatives of {CuII(PrP(106–114))}. The XANES region of the Cu K-edge X-ray absorption spectra of Cu(M109I), Cu(M112I), and Cu(M109/112I) are displayed in Fig. 3. Both Cu(M109I) and Cu(M112I) display weak Cu(1s → 3d) transitions at ~8979 eV and Cu(1s → 4p + LMCT) transitions at ~8983 eV, the latter of which are barely resolvable from the edges (Table 2).[50,51] This is nearly identical to what was observed for the parent metallopeptide {CuII(PrP(106–114))}, which contains CuII in a square planar coordination environment with one S and three mixed N/O ligands.[17] In contrast Cu(M109/112I) displays well resolved Cu(1s → 4p + LMCT) and Cu(1s → 4p) transitions at 8982.8(2) and 8989.1(1) eV, respectively. In addition there is a weak Cu(1s → 3d) transition at 8978.8(4) eV. The edge shape of Cu(M109/112I) is thus more consistent with what has been observed for CuII contained in square planar N4 coordination environments.[50]

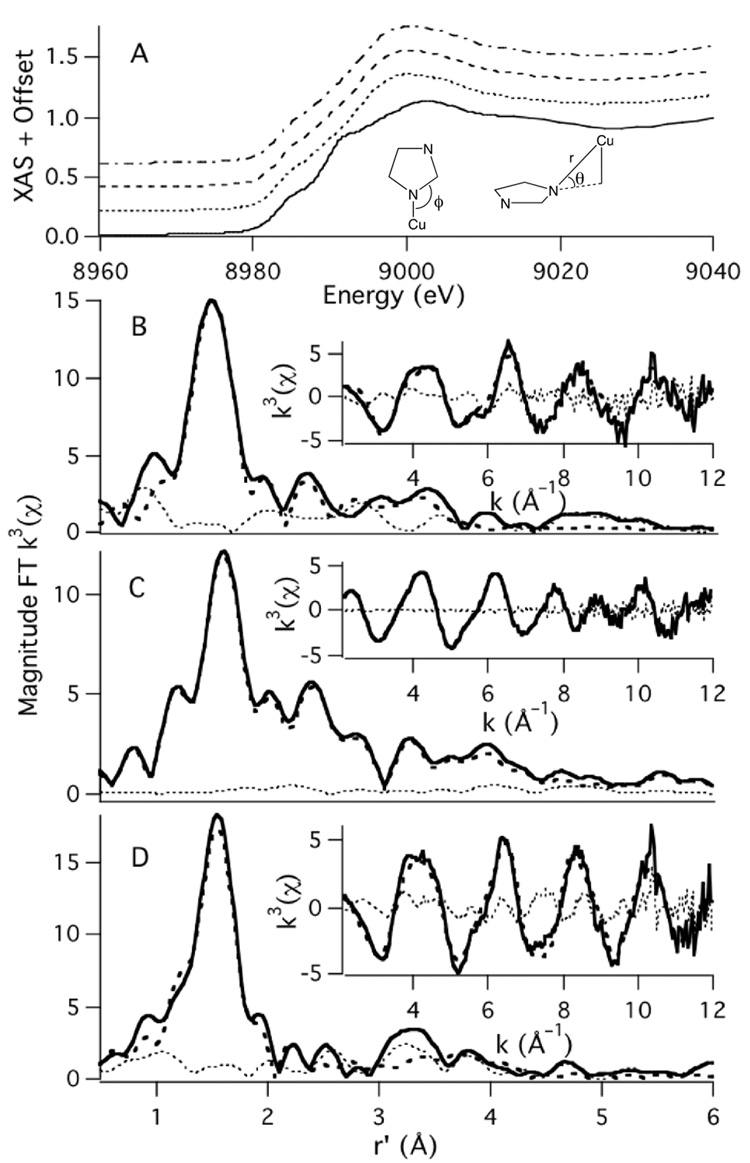

Fig. 3.

A: Depicts the XANES region of the Cu K-edge X-ray absorption spectra of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} (dotted and dashed spectrum), Cu(M109I) (dashed), Cu(M112I) (dotted) and Cu(M109/112I) (solid). The metrical parameters refined for in the imidazole phase and amplitude function are also depicted in A. The magnitude FT k3 EXAFS and k3 EXAFS (insets) of Cu(M109I) (B), Cu(M112I) (C), and Cu(M109/112I) (D) are also depicted. The experimental data are depicted as the solid spectrum, the best fit to the data are the dashed spectrum, and the difference spectrum are the dotted spectrum.

Table 2.

Cu K-edge X-ray absorption data for {Cu(PrP(106–114))}, Cu(M109I), Cu(M112I), and Cu(M109/112I).

| {CuII(PrP(106–114))}a | Cu(M109I) | Cu(M112I) | Cu(M109/112I) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-edge Peak #1 | 8978.9(3) eV | 8979.1(4) eV | 8979.4(3) eV | 8978.8(4) eV |

| (area = 0.035(7) eV) | (area = 0.03(1) eV) | (area = 0.02(1) eV) | (area = 0.03(1) eV) | |

| Pre-edge Peak #2 | 8983.0(4) | 8983.6(8) eV | 8983.5(6) eV | 8985.1(1) eV |

| (area = 0.07(2) eV) | (area = 0.09(3) eV) | (area = 0.08(2) eV) | (area = 0.11(2) eV) | |

| Pre-edge Peak #3 | ---- | ---- | ---- | 8992.0(4) eV |

| (area = 0.09(2) eV) | ||||

| Eob | 8989.6 eV | 8989.1 eV | 8988.2 eV | 8990.3 eV |

| N-shell | ||||

| nc | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| r (Å) | 1.964(3) | 1.966(8) | 1.959(14) | 1.94(1) |

| σ2 (Å2) | 0.002(1) | 0.002(2) | 0.002(1) | 0.005(2) |

| S-shell | ||||

| nc | 1 | 1 | 1 | ---- |

| r (Å) | 2.301(8) | 2.32(1) | 2.32(1) | |

| σ2 (A2) | 0.008(2) | 0.007(1) | 0.004(1) | |

| Im-shell | ||||

| n | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| r (Å)d | 1.965 | 1.966 | 1.959 | 1.94 |

| σ2 (Å2) | 0.003(1) | 0.002e | 0.003(2) | 0.009(8) |

| θ | 19(4) | 34(11) | 8(3) | 18(7) |

| ϕ | 131(9) | 134(2) | 130(15) | 127(11) |

| GOF | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.74 | 0.92 |

The data from reference 17 was re-refined to be consistent with the refinements from this study.

The energy at which EXAFS starts. This was initially set as a free parameter for the first shell in the refinements, and then in all subsequent refinement cycles was restrained to the value listed.

This parameter was initially a free variable and then set to the nearest whole number.

The imidazole (Im) shell was restrained to the distance of the N-shell.

The value of σ2 for this shell in Cu(M109I) kept yielding a negative number in the refinements, which is not physically possible. Therefore, this value was restrained to that of the innersphere N-shell. We suspect this is a consequence of the large tilt angle, leading to weak outersphere scattering at moderate r values. Therefore, other outersphere interactions not associated with the imidazole ring (i.e. from the peptide chelate) are being accounted for in the Im function inducing a negative value for σ2 in the refinement of this shell when this parameter is allowed to freely refine.

We find that the EXAFS region for Cu(M109/112I) is best modeled as a 4-coordinate Cu center with one imidazole N ligand and three additional N/O donors, with average N/O bond lengths of 1.94(1) Å (Fig. 3, Table 2). In contrast, the EXAFS region of both Cu(M109I) and Cu(M112I) are best modeled with CuII contained in 4-coordinate ligand environments with one N-donor from the imidazole of H(111), two additional N/O donors, and one sulfur donor. For both Cu(M109I) and Cu(M112I) the average Cu-N bond length refined to ~1.96 Å, which is nearly identical to what was found in {CuII(PrP(106–114))}. In addition, we are able to locate a short Cu-S scatterer for both Cu(M109I) and Cu(M112I) at ~2.32 Å, which also compares well with the Cu-S scatterer distance of 2.30 Å previously found for {CuII(PrP(106–114))}.

Use of a multiple scattering (MS) analysis allowed us to extract angular parameter for the H(111) imidazole ligand ligated to CuII. Previously we found that the imidazole moiety for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} was best modeled with the imidazole ring system positioned with the in-plane Cu-N-C bond angle (ϕ) of 131(9)° and an out-of-plane bond angle (θ) of 19(4)° (Table 2).[17] For Cu(M109I), which contains the Met thioether ligand towards the C-terminus of the peptide relative to H(111), the relevant bond angles are ϕ = 134(2)° and θ = 34(11)°, implying that the imidazole must undergo a substantial tilt to coordinate the CuII ion. This can be contrasted with Cu(M112I), where ϕ = 130(15)° and θ = 8(3)°. This demonstrates that coordination of the Met(109) thioether, which is towards the N-terminus relative to H(111), allows the imidazole ligand to adopt a geometry more optimal for Cu-N(imidazole) bonding.

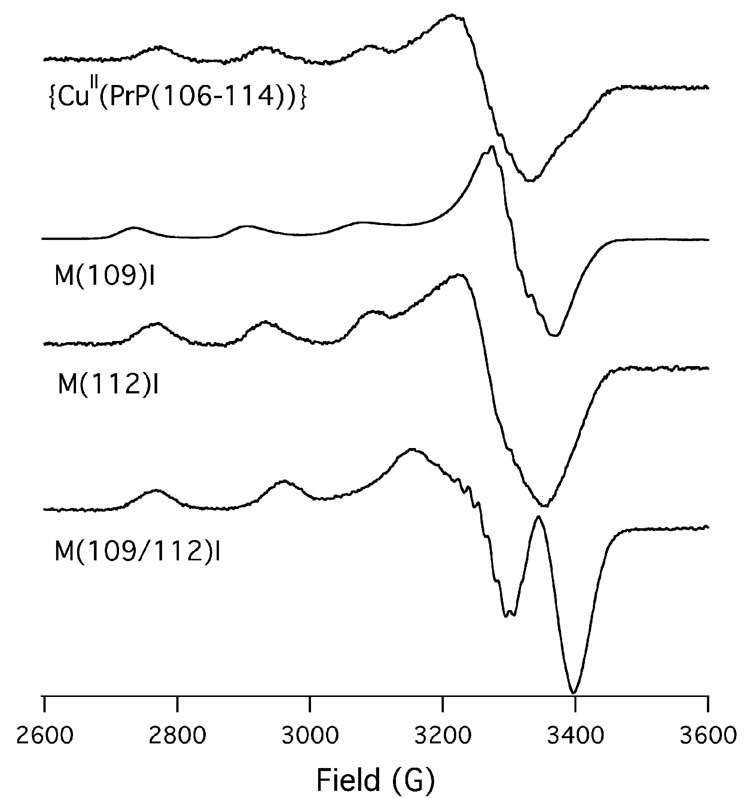

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} and its M(nnn)I Derivatives

The 20 K X-band EPR spectra of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} and the three {CuII(PrP(106–114)(M(nnn)I))} derivatives are depicted in Fig. 4. The EPR spectra of the three metallopeptides containing Met thioethers all appear to be similar to one another, indicating similar coordination environments. In contrast Cu(M109/112I) displays an EPR spectrum distinct from the other three metallopeptides, indicative of a different coordination environment about CuII within this metallopeptide when compared to the other three metallopeptides. This is consistent with our findings by X-ray absorption spectroscopy.

Fig. 4.

X-band EPR spectra of {CuII(PrP(106–114))}, Cu(M109I), Cu(M112I), and Cu(M109/112I) obtained at 20 K in 1:1 buffer:glycerol glasses (buffer = 50 mM NEM; pH 7.4).

Although the EPR spectrum of Cu(M109/112I) is reminiscent of spectra obtained for CuII within N4 coordination geometries,[52] we could not adequately simulate its EPR spectrum. This seems to suggest that Cu(M109/112I) contains CuII within a mixture of different coordination environments. Such a finding implies that the Met thioether ligands are required for the formation of a stable well-defined CuII coordination environment.

In contrast to Cu(M109/112I), the EPR spectra of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} Cu(M109I) and Cu(M112I) are all similar to square planar CuII containing complexes with N3O coordination.[52] Furthermore, we can simulate the EPR spectra of all three Met-containing metallopeptides using g∥ ~ 2.223 and A∥ ~ 457 MHz (Table 3). As pointed out by Viles and coworkers,[13] the fact that the EPR spectra are similar to CuIIN3O complexes is not necessarily inconsistent with N2OS coordination as there are few well defined CuII coordination complexes with square planar N2OS coordination for comparison. It is therefore possible that CuII within an N2OS ligand environment could yield an EPR spectrum similar to CuII within an N3O ligand environment. In the next section we will demonstrate that the EPR parameters observed for {CuII(PrP(106–114))}, Cu(M109I), and Cu(M112I) are in fact wholly consistent with square planar CuIIN2OS complexes possessing short CuII–Sthiother bonds.

Table 3.

Experimentally derived EPR parameters for {CuII(PrP(106–114))}, Cu(M109I), and Cu(M112I), [(LSEP)CuII(H2O)(OClO3)]+, [(pbnap)Cu-OMe]+ and the computationally determined EPR parameters for [(LSEP)CuII(H2O)(OClO3)]+, [(pbnap)Cu-OMe]+, [CuII(KH)O]+, [CuII(KH)N]+, and [CuII(GKH)]+.

| g∥ | g⊥ | A∥(MHz) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| {CuII(PrP(106–114))} | 2.223 | 2.028 | 459a |

| Cu(M109I) | 2.221 | 2.014 | 462a |

| Cu(M112I) | 2.223 | 2.029 | 456a |

| [(LSEP)CuII(H2O)(OClO3)]+ | |||

| experimentalb | 2.23 | 2.03 | 476a |

| calculatedc | 2.188 | 2.055 | −503 |

| [(pbnap)Cu-OMe]+ | |||

| experimentald | 2.244 | 2.060 | 460a |

| calculatedc | 2.183 | 2.055 | −486 |

| [CuII(KH)O]+ | 2.185 | 2.046 | −491 |

| [CuII(KH)N]+ | 2.114 | 2.034 | 307 |

| [CuII(GKH)]+ | 2.1s31 | 2.038 | −449 |

All three complexes with potential thioether ligands also display g⊥ ~ 2.02. We find that Cu(M109I) displays a g⊥ = 2.014 while Cu(M112I) displays a g⊥ = 2.029. A close inspection of the EPR spectrum for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} shows that the g⊥ component displays two features: a prominent feature at g = 2.028 and a shoulder at 2.012. It therefore seems reasonable to conclude that {CuII(PrP(106–114))} is a mixture of two different structures; the major component with M(109) thioether coordination, and the minor component with M(112) thioether coordination.

In this light both the EXAFS and CD data make more sense. The MS analysis of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} placed the angular parameters for the imidazole moiety in between Cu(M109I) and Cu(M112I). This is what would be expected for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} if it were a “mixture” of the Cu(M109I) and Cu(M112I) structures. This is because the parameters obtained from the EXAFS refinements for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} would be for the average structure of the CuII center. Furthermore, the CD data for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} also suggests it is a mixture of the Cu(M109I) and Cu(M112I) structures. By combining the CD spectra for Cu(M109I) and Cu(M112I) we can simulate the {CuII(PrP(106–114))} spectrum reasonably well (Fig. 5) assuming a 5:3 mixture of Cu(M112I):Cu(M109I). As with the EPR data, this is consistent with the major contribution to the {CuII(PrP(106–114))} structure resulting from M(109) providing a thioether ligand for CuII.

Fig. 5.

Simulation (thick solid spectrum) of the spectrum of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} (thick dotted-dashed spectrum) using a 5:3 ratio of the spectra of Cu(M112I) (thin dotted spectrum) and Cu(M109I) (thin dashed spectrum).

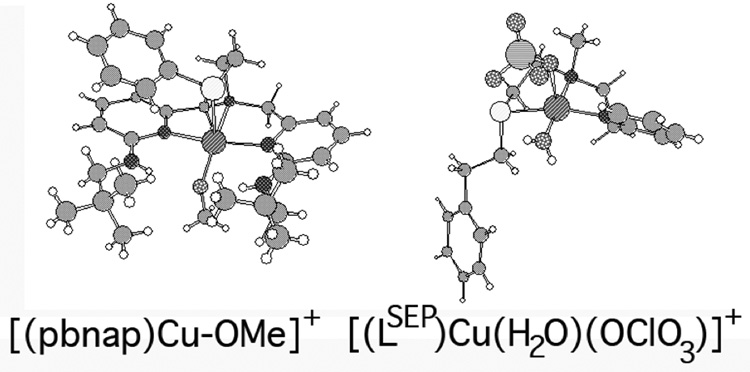

Electronic Structure Calculations

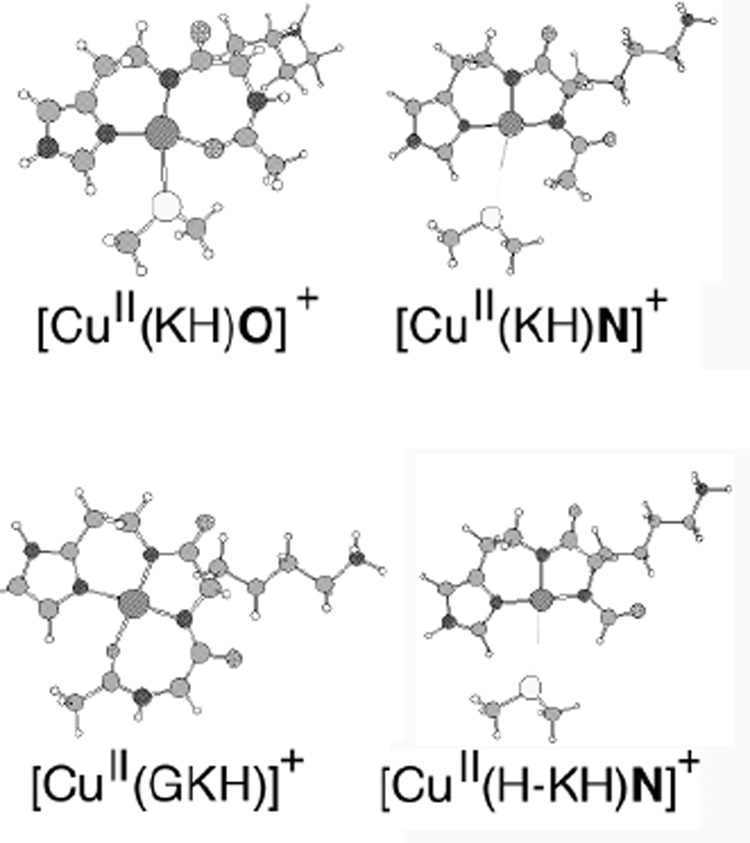

To gain additional insight into the CuII coordination environment of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} we performed electronic structure calculations on minimized peptide models. One series of peptide based models were used to examine carbonyl oxygen coordination to the CuII center. These consisted of the peptide sequence (AcN-KH) with the C-terminal carboxylate removed from the His residue. CuII was then ligated to the peptide sequence in one of two fashions: either 1) through the imidazole-δ-nitrogen and amide nitrogens from H and K ([CuII(KH)N]+), or 2) through the imidazole-δ-nitrogen, the amide nitrogen from H, and the carbonyl oxygen from the Ac-group ([CuII(KH)O]+). A Me2S group was then ligated to the CuII center. In the case of CuN3S coordination the nitrogen of the K side-chain was protonated to assure charge balance between the two peptides (+1 in both cases, Chart 3). In addition to these two models, a CuII peptide with the sequence AcN-GKH was also investigated (CuII(GKH)). Here the carboxylate group was removed from the H residue, and then CuII was coordinated by three nitrogens (the imidazole-δ-nitrogen, and two backbone amide nitrogens) and a carbonyl oxygen from the Ac group.

Chart 3.

Structures of [(pbnap)Cu-OMe]+ and [(LSEP)Cu(H2O)(OClO3)]+.

Geometry optimized structures (Table 4) for the four models were obtained using standard DFT methods (BP/VWN functional; TZDP basis set) with the conductor like screening model (COSMO) to approximate the influence of the effects of water as a solvent (ε = 78.9; r = 1.3 Å).[42,43] In all cases only the δ-nitrogen of the imidazole ring was found to provide a stable ligand environment for CuII. We found that highly unfavorable coordination geometries about CuII were imposed by ligation of the imidazole ε-nitrogen. Therefore such structures are at considerably higher energies than those with imidazole δ-nitrogen coordination.

Table 4.

Selected metrical parameters for [CuII(KH)O]+, [CuII(KH)N]+, [CuII(H–KH)N]+, and [CuII(GKH)]+.

| [CuII(KH)O]+ | [CuII(KH)N]+ | [CuII(H-KH)N]+ | [CuII(GKH)]+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu-NIm | 1.948 Å | 1.913 Å | 1.907 Å | 1.978 Å |

| Cu-Namide | 1.985 Å | 1.949 Å | 1.951 Å | 1.946 Å |

| Cu-O/Cu-N | 1.929 Å | 1.881 Å | 1.879 Å | 1.928 Å |

| Cu-S/Cu-O | 2.344 Å | 3.592 Å | 3.586 Å | 2.078 Å |

| S/O-Cu-Namide | 159.4° | 153.9° | 155.4° | 170.7° |

| NIm-Cu-O/N | 162.6° | 172.6° | 171.5° | 168.0° |

| NIm-Cu-Namide | 98.7° | 97.1° | 96.8° | 92.6° |

| Namide-Cu-N/O | 98.3° | 84.7° | 84.8° | 84.4° |

| N/O-Cu-S/O | 72.4° | 104.2° | 102.7° | 99.1° |

| S/O-Cu-NIm | 92.5° | 77.3° | 79.3°å | 85.6° |

The first two structures investigated were [CuII(KH)N]+ and [CuII(KH)O]+ to determine the likelihood of mono-([CuII(KH)O]+) vs. bisamide ([CuII(KH)N]+) coordination for CuII within {CuII(PrP(106–114))}. It has been reasoned that either of these two structures may be considered as reasonable for CuII coordination to the peptide at physiological pH.[15,24] The DFT calculations on the other hand strongly argue against bis-amide coordination.

Comparing the DFT geometry optimized structures of [CuII(KH)N]+ and [CuII(KH)O]+ one is struck by a profound difference between the two; the Cu-S bond in [CuII(KH)N]+ is lengthened by over 1.2 Å (Cu-S bond length = 3.57 Å) compared to [CuII(KH)O]+ (Cu-S bond length = 2.34 Å). In [CuII(KH)N]+ the Cu-S interaction can best be described as non-bonding as the Cu-S distance is too long to be considered a bonding interaction. Therefore, the CuII center can be described as possessing a pseudo-T-shaped Cu(N)3 geometry. As most substantial structural cis influences are steric in origin[53–55] we also performed the calculation on the [CuII(KH)N]+ derivative [CuII(H-KH)N]+, which has the acetyl-methyl group replaced with a hydrogen (Chart 3). We find that this structural modification had a minimal influence on the structure of the CuII metallopeptide fragment of [CuII(KH)N]+ vs. [CuII(H-KH)N]+; only a 0.06 Å shortening of the Cu-S bond was obtained upon removal of the methyl group. This lengthening of the Cu-S bond therefore appears to truly be an electronic effect. We speculate the reason for this may be the increase in positive charge in the xy plane about the CuII center of [CuII(KH)O]+ vs. [CuII(KH)N]+. This would create a stronger interaction between the hard Lewis acidic CuII center and the soft and weakly Lewis basic thioether in [CuII(KH)O]+ vs. [CuII(KH)N]+, thus leading to a shorter Cu-S bond in [CuII(KH)O]+.

Time dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) was next used to gain insight into the nature of the Cu-S interaction.[56] To verify the validity of these methods we probed the electronic absorption spectra of two cationic transition metal complexes containing CuII within mixed N/O/S coordination environments: Karlin’s [(LSEP)CuII(H2O)(OClO3)]+ and Berreau’s [(pbnap)Cu-OMe]+ (Chart 3).[57,58] Both of these complexes are five coordinate, but Karlin’s [(LSEP)CuII(H2O)(OClO3)]+ contains the thioether ligand in the xy plane while Berreau’s [(pbnap)Cu-OMe]+ contains the thioether ligand along the z-axis. For both complexes the TD-DFT calculations underestimate the energy of the low-energy ligand–field transitions by ~1500 cm−1 placing them between 650 – 750 nm as opposed to between 550 – 650 nm. In contrast, the TD-DFT calculations slightly overestimate the energies of the Sthioether → Cu(3d) transitions by ~800 cm−1. For [(pbnap)Cu-OMe]+ the TD-DFT calculations place the main Sthioether → Cu(3d) transition at 320 nm (as opposed to 330 nm).[58] In the case of [(LSEP)CuII(H2O)(OClO3)]+ the two (vide infra) main Sthioether → Cu(3d) transitions are found at 342 and 359 nm (as opposed to the centered band at 365 nm).[57] The inherent low errors and apparent systematic derivations from experimental electronic absorption spectra therefore support the use of these methods for aiding in band assignments from electronic absorption and CD data for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} using our cationic computational models.

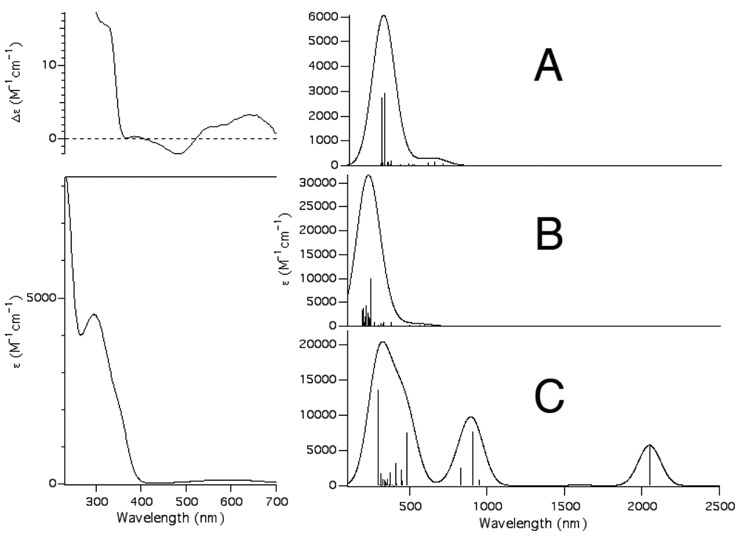

Fig. 6 displays the TD-DFT calculated absorption spectrum for [CuII(KH)O]+ employing the COSMO solvation model for water. As can be seen there is reasonable agreement between the experimental electronic absorption spectrum for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} and the computational electronic absorption data for [CuII(KH)O]+. Experimentally we find that all of the transitions above 350 nm in wavelength observed for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} can be best described as ligand field transitions (ε < 130 M−1 cm−1), with the best resolved series of ligand-field transitions found at ~600 nm. The TD-DFT calculations for [CuII(KH)O]+ show all of the ligand-field transitions taking place below 350 nm, with well resolved transitions taking place at lower wavelengths (~670 nm). At higher wavelengths there is a relatively intense transition at ~320 nm (ε = 4710 M−1 cm−1) and a shoulder at 340 nm in the experimental pH 7.4 electronic absorption spectrum of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} (Fig. 7). Based on the TD-DFT calculations and the CD spectrum of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} we assign these transition as the SMet → Cu LMCTs. The TD-DFT calculations suggest that the major contribution to this band are two SMet(σ) → Cu(3d) transitions. Both of these transitions, which occur at 312 nm (f = 0.0126) and 329 nm (f = 0.0133) (Fig. 7A), can be best described as S(σ)/Cu(3d)/N(σ)/O(σ) → Cu(3dx2–y2)/S(σ)/N(σ)/O(σ)* in origin (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

The left hand figures depict the CD spectrum (top) and electronic absorption spectrum (bottom) of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} highlighting the SMet → Cu(3d) transition. The right hand figures depict the calculated spectra for [CuII(KH)O]+ (A), [CuII(GKH)]+ (B), and [CuII(KH)N]+ (C). For the simulated spectra a line-width at half-height of 1000 cm−1 was used for all transitions.

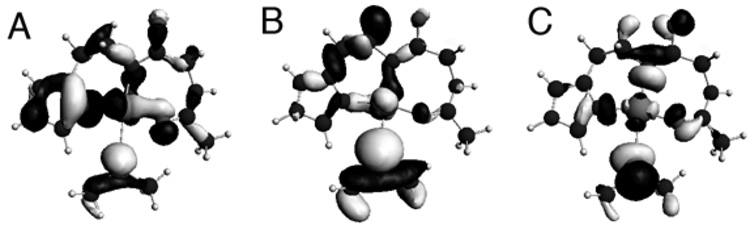

Fig. 7.

Isosurface plots of the MOs for [CuII(KH)O]+ that make up the leading configuration for the ground states (A and B) and excited state (C) for the two S(σ)/Cu(3d)/N(σ)/O(σ) → Cu(3dx2–y2)/S(σ)/N(σ)/O(σ)* transitions. The lysine side-chain has been removed for clarity.

The TD-DFT calculations show a completely different calculated electronic absorption spectrum for the CuN3 T-shaped compound [CuII(KH)N]+. The calculated spectrum obtained for [CuII(KH)N]+ is entirely inconsistent with the experimental absorption spectrum for {CuII(PrP(106–114))}; it contains a series of low energy charge transfer bands due to a series of low lying ligand based orbitals that are “within” the 3d-manifold. In addition, the calculated S(σ) → Cu(3d) transitions have virtually no intensity (f = 0.03 × 10−3) due to poor overlap between the S(σ) and Cu(3d) orbitals. It therefore appears unlikely that the [CuII(KH)N]+ structure is physiologically relevant, which appears to rule out a “four” coordinate N3S CuII center with bis-amide ligation.

It has been also been speculated that the coordination environment about CuII within {CuII(PrP(106–114))} could be a square planar bis-amide CuIIN3O coordination motif.[15,59] Therefore the peptide [CuII(GKH)]+, which contains CuII within a bis-amide N3O coordination environment, was also investigated by TD-DFT. This metallopeptide yielded an electronic absorption spectrum that contains its first series of ligand field bands approximately 3700 cm−1 higher in energy than found in [CuII(KH)O]+. This is consistent with what is observed for the high pH spectrum of {CuII(PrP(106–114))},[24] which depicts a blue shift in the ligand-field transitions by 1442 cm−1, and likely does not contain a S-based ligand to CuII.

We next turned our attentions to simulating the EPR spectra of the three metallopeptide based models. All EPR calculations utilized the B3LYP functional and the coupled-perturbed SCF equations to account for spin-orbit coupling and magnetic field effects.[45,60] For square planar CuII complexes the calculation of EPR parameters using such methods typically have errors of less than 5% when employing the B3LYP functional.[45] As with the TD-DFT calculations, we also explored Karlin’s [(LSEP)CuII(H2O)(OClO3)]+ and Berreau’s [(pbnap)Cu-OMe]+ CuII complexes by these methods to determine if they are capable of accurately reproducing experimental data for CuII within a mixed N/O/Sthioether coordination environment. As can be seen in Table 3, these methods accurately reproduce the EPR spectra of these transition metal compound with apparent systematic deviations. It appears that these methods slightly overestimate g⊥ and the magnitude of A∥ while underestimate g∥ This is consistent with what has been previously observed with these methods for other systems.[45, 61]

All three metallopeptide complexes yield similar computational g-values (Table 3). When the errors inherent in the computational vs. experimental data are considered [CuII(KH)O]+ yielded the g-values (g∥ = 2.185, g⊥;= 2.046) that were more consistent with the data for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} than [CuII(KH)N]+ (g∥; = 2.114 and g⊥= 2.034) or [CuII(GKH)]+ (g∥ = 2.131 and g⊥= 2.038). We next turn our attention to the hyperfine coupling constant A∥. For [CuII(KH)O]+ we calculate an A∥ = −491 MHz, with [CuII(KH)N]+ and [CuII(GKH)]+ yielding an A∥ of 307 and −449 MHz, respectively. As stated, these methods have a tendency to overestimate A∥ and g⊥ while they underestimate g∥ for CuII complexes. This implies that the calculated data for [CuII(KH)O]+ is the best complement to the experimental data for {CuII(PrP(106–114))}.

Examination of the EXAFS data clearly shows that there are short Cu-S interactions in all three metallopeptides containing a Met residue. DFT calculations show that this is consistent with a four coordinate CuII complex with equatorial SMet ligation and one anionic amide donor. Furthermore, the EPR data, electronic transitions, and electronic-structure/excited-state calculations are all consistent with {CuII(PrP(106–114))} having a N(imidazole)N(amide)O(carbonyl)S(Met) ligand environment. Therefore we favor this ligand environment for {CuII(PrP(106–114))} at physiological pH with either M(109) or M(112) residues providing thioether ligands to CuII.

We note that in a recent study by Klewpatinond and Viles an N4CuII and N3OCuII ligand environment was predicted to be the preferred structure for CuII within the amyloidogenic PrP fragment. At physiological pH the N3OCuII coordination mode was predicted to be the dominant structure based on EPR spectroscopy.[59] The structure for the proposed N3OCuII coordination mode by Viles is similar to the computational model [CuII(GKH)]+ that was explored above. As we have demonstrated the EPR parameters for the N3OCuII vs. N2OSCuII coordination modes are similar to one another. It is therefore possible that Viles and coworkers may have also been observing an N2OSCuII center in their study as well.

Summary and Biological Implications

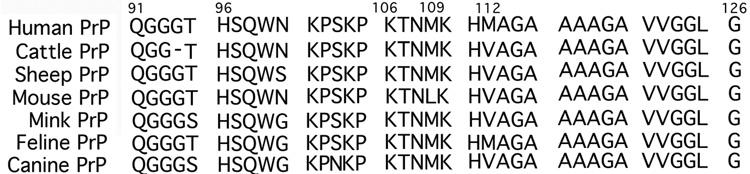

We have provided evidence that the human PrP fragment PrP(106–114), and by analogy PrP(91–126), will utilize both M(109) and M(112) independently to coordinate CuII within an N2OS square planar coordination environment. When either M(109) or M(112) are eliminated from the PrP(106–114) the resulting peptide is still capable of coordinating CuII but with diminished copper affinity. If both Met residues are eliminated the copper affinity of the peptide is dramatically reduced. A survey of several mammalian PrP sequences (Fig. 8)[15,62,63] reveals that H(111) is strictly conserved and M(109) is highly conserved. M(112), which is not as heavily favored for CuII ligation in PrP(106–114) as M(109), is not conserved within mammalian protein sequences. This would imply that the affinity for CuII at physiological pH among other mammalian PrP(91–126) fragments would be similar, although slightly decreased, when compared to human PrP(91–126).

Fig. 8.

Alignment of various mammalian PrP primary protein sequences corresponding to PrP(91–126) from humans.

In a previous study we found that {CuII(PrP(106–114))} (and {CuII(PrP(91–126))}) was redox active, and displayed a quasireversible CuII → CuI reduction couple at −0.33 V vs. Ag/AgCl.[17] Upon reduction to CuI the copper center became ligated in a mixed S2(N/O)2 ligand environment. It was reasoned that the two S ligands were derived from M(109) and M(112). Here we find that when either M(109) or M(112) are removed from the primary sequence of {CuII(PrP(106–114))} the reduction of CuII is no longer reversible and it takes place a substantially more negative potential (~ −0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl; Table 1). It therefore seems reasonable to conclude that in most mammalian species CuII coordination to this region of the PrP would render it redox inactive, similar to what has been observed for the CuII adduct of the octarepeat domain.[64] It would only be in a few species, such as humans and felines, that redox active CuII would be produced by coordinating copper to this region of the PrP.

On first blush it may appear that this region of the PrP in many species may play a protective role against oxidative damage by free CuII. Coordination of CuII to PrP(106–114) would render it redox inactive, and therefore eliminate unwanted redox side-reactions facilitated by copper. Only in a few unfortunate species, such as in humans, would CuII be redox active, and thus promote oxidative damage. However, this supposition overlooks one important factor. For this region of the PrP to produce a redox active copper ion (or sequester CuII in a redox inactive state) copper would have to coordinate to this region in the first place. The CuII Kd values we observe for PrP(106–114) and its derivatives are in the mid to high µM range. This is many orders of magnitude higher than the octarepeat domain of the PrP,[12,15–18] which can coordinate four CuII ions per protein in a redox inactive state. It therefore appears highly unlikely that CuII would coordinate to this region of the PrP under physiologically relevant conditions.

Chart 2.

DFT minimized structures of the computational metallopeptide models used in the study. Selected metrical parameters for these models are presented in Table 4.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Prof. Veronika Szalai (University of Maryland, Baltimore County) for use of her EPR spectrometer and invaluable experimental assistance. We also thank Prof. Martin Kirk (University of New Mexico) for valuable discussions. This work was supported, in part, by NIH Grant Number P20 RR-016464 from the INBRE program of the National Center for Research Resources. XAS data were recorded at the National Synchrotron Light Source, which is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy, under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886.

Abbreviations

- TSEs

transmissible spongiform encephalopathies

- PrP

prion protein

- PrPc

cellular isoform of the prion protein

- PrPSc

scrapie isoform of the prion protein

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- ENDOR

electron nuclear double resonance

- CD

circular dichroism

- EXAFS

extended X-ray absorption fine structure

- XANES

X-ray absorption near edge structure

- XAS

X-ray absorption spectroscopy

- ESI-MS

electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- M+

parent ion (positive ion)

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- rp-HPLC

reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography

- LMCT

ligand to metal charge transfer

- TD-DFT

time dependent density functional theory

- COSMO

conductor-like screening model

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Taylor JP, Hardy J, Fischbeck KH. Science. 2002;296:1991–1995. doi: 10.1126/science.1067122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fillit HM, O’Connell AW, Brown WM, Altstiel LD, Anand R, Collins K, Ferris SH, Khachaturian ZS, Kinoshita J, Van Eldik L, Dewey CF. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2002;16:S1–S8. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200200001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins S, McLean CA, Masters CL. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2001;8:387–397. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prusiner SB. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edkes HK, Wickner RB. Nature. 2004;430:977–979. doi: 10.1038/430977a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prusiner SB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:13363–13383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prusiner SB. Science. 1997;278:245–251. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castilla J, Saa P, Hertz C, Soto C. Cell. 2005;121:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nunziante M, Gilch S, Schaetzl HM. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:1268–1284. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott MR, Will R, Ironside J, Nguyen HO, Tremblay P, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Proc. Nat;. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:15137–15142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grist EPM. Creutzfeld-Jakob Disease. 2007:127–146. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaggelli E, Kozlowski H, Valensin D, Valensin G. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1995–2044. doi: 10.1021/cr040410w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones CE, Klewpatinond M, Abdelraheim SR, Brown DR, Viles JH. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:1393–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stockel J, Safar J, Wallace AC, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7185–7193. doi: 10.1021/bi972827k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millhauser GL. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:79–85. doi: 10.1021/ar0301678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walter ED, Chattopadhyay M, Millhauser GL. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13083–13092. doi: 10.1021/bi060948r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shearer J, Soh P. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:710–719. doi: 10.1021/ic061236s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson GS, Murray I, Hosszu LLP, Waltho JP, Clarke AR, Collinge J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:8531–8535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151038498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calzolai L, Lysek DA, Perez DR, Guntert P, Wuthrich K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:651–655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408939102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuwata K, Kamatari YO, Akasaka K, James TL. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4439–4446. doi: 10.1021/bi036123o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viles JH, Donne D, Kroon G, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2743–2753. doi: 10.1021/bi002898a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baskakov IV, Legname G, Baldwin MA, Pruisner SB, Cohen FE. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21140–21148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasnian SS, Murphy LM, Strange RW, Grossmann JG, Clarke AR, Jackson GS, Collinge J. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:467–473. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Natale G, Grasso G, Impellizzeri G, La Mendola D, Micera G, Mihala N, Nagy Z, Õsz K, Pappalardo G, Rigó V, Rizzarelli E, Sanna D, Sóvágó I. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:7214–7215. doi: 10.1021/ic050754k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns CS, Arnooff-Spencer E, Legname G, Prusiner SB, Antholine WE, Gerfen GJ, Peisach J, Millhauser GL. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6794–6803. doi: 10.1021/bi027138+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones CE, Abdelraheim SR, Brown DR, Viles JH. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32018–32027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viles JH, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Goodin DB, Wright PE, Dyson JH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2042–2047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown DR, Qin K, Herms JW, Madlung A, Manson J, Strome R, Fraser PE, Kruck T, vonBohlen A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Giese A, Westaway D, Kretzschmar H. Nature. 1997;390:684–687. doi: 10.1038/37783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pauly PC, Harris DA. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33107–33110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nigels M. Simpip. Urbana-Champaign, Il: University of Illinois; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rusling JF, Nassar A-EF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:11891–11897. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scarrow RS. EXAFS123. Haverford, PA: Haverford College; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ankudinov AL, Ravel B, Rehr JJ, Conradson SD. Phys. Rev. B. 1998;58:7565. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Te Velde G, Bickelhaupt FM, Baerends EJ, Guerra CF, Van Gisbergen SJA, Snijders JG, Ziegler T. J. Comp. Chem. 2001;22:931–967. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neese F. ORCA, version 2.6.35; an ab initio, density functional, and semiempirical program package. Germany: Institute for Physical and Theoretical Chemistry Universität Bonn; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vosko SJ, Wilk M, Nussair M. Can. J. Phys. 1980;58:1200–1211. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Becke A. J. Chem. Phys. 1986;84:4524–4529. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becke A. J. Chem. Phys. 1988;88:1053–1062. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becke A. Phys. Rev. A. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perdew JP. Phys. Rev. B. 1986;34:7406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perdew JP. Phys. Rev. B. 1986;33:8822–8824. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klamt A. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;99:2224–2235. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klamt A, Jones V. J. Chem. Phys. 1996;105:9972–9981. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Leeuwen R, Baerends EJ. J. Phys. Rev. A. 1994;49:2421–2431. doi: 10.1103/physreva.49.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nesse F. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;118:3939–3948. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:1372–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee CT, Yang WT, Parr RG. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaefer A, Horn H, Ahlrichs R. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;97:2571. [Google Scholar]

- 50.DuBois JL, Mukherjee P, Stack TDP, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Hodgson KO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:5775–5787. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kau L-S, Spira-Solomon DL, Penner-Hahn JE, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:6433–6442. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peisach J, Blumberg WE. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1974;165:691–708. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(74)90298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhuyan M, Laskar M, Mandal D, Gupta BD. Organometallics. 2007;26:3559–3567. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta BD, Qanungo K, Organomet J. Chem. 1997;543:213–220. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arnold DP, Bennett MA. Inorg. Chem. 1984;23:2117–2124. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neese F. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2006;11:702–711. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee Y, Lee D-H, Narducci-Sarjeant AA, Zakharov LN, Rheingold AL, Karlin KD. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:10098–10107. doi: 10.1021/ic060730t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tubbs KJ, Fuller AL, Bennett B, Arif AM, Berreau LM. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:4790–4791. doi: 10.1021/ic034661j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klewpatinond M, Viles JH. Biochem. J. 2007;404:393–402. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neese F. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003;7:125–135. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fiedler AT, Bryngelson PA, Maroney MJ, Brunold TC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5449–5462. doi: 10.1021/ja042521i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lysek D, Nivon L, Wuthrich K. Gene. 2004;341:249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee IY, Westway D, Smit AFA, Wang K, Seto J, Chem L, Acharya C, Ankener M, Baskin D, Cooper C, Yao H, Prusiner SB, Hood LE. Genome Res. 1998;8:1022–1037. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.10.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bonomo RP, Impellizzeri G, Pappalardo G, Rizzarelli E, Tabbi G. Chem. Eur. J. 2000;6:4196–4202. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20001117)6:22<4195::aid-chem4195>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]