Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is a chronic syndrome in which pathological cardiac remodeling is an integral part of the disease and mast cell (MC) degranulation-derived mediators have been suggested to play a role in its progression. Protein kinase C (PKC) signaling is a key event in the signal transduction pathway of MC degranulation. We recently found that inhibition of εPKC slows down the progression of hypertension-induced HF in salt-sensitive Dahl rats fed a high-salt diet. We therefore determined whether εPKC inhibition affects MC degranulation in this model. Six week-old male Dahl rats were fed with a high-salt diet to induce systemic hypertension, which resulted in concentric left ventricular hypertrophy at the age of 11 weeks, followed by myocardial dilatation and HF at the age of 17 weeks. We administered εV1-2 an εPKC-selective inhibitor peptide (3 mg/Kg/day), δV1-1, a δPKC-selective inhibitor peptide (3 mg/Kg/day), TAT (negative control; at equimolar concentration; 1.6 mg/Kg/day) or olmesartan (angiotensin receptor blocker [ARB] as a positive control; 3mg/Kg/day) between 11 weeks and 17 weeks. Treatment with εV1-2 attenuated cardiac MC degranulation without affecting MC density, myocardial fibrosis, microvessel patency, vascular thickening and cardiac inflammation in comparison to TAT- or δV1-1-treatment. Treatment with ARB also attenuated MC degranulation and cardiac remodeling, but to a lesser extent when compared to εV1-2. Finally, εV1-2 treatment inhibited MC degranulation in isolated peritoneal MCs. Together, our data suggest that εPKC inhibition attenuates pathological remodeling in hypertension-induced HF, at least in part, by preventing cardiac MC degranulation.

Keywords: Mast cell degranulation, protein kinase C, PKC-selective inhibitor peptide, cardiac remodeling, heart failure

1. Introduction

A continual increase in cardiac demand due to pressure overload (e.g., hypertension or aortic stenosis), volume overload (e.g., valvular regurgitation) or cardiac injury (e.g., following myocardial infarction or myocarditis) can lead to maladaptive remodeling and heart failure (HF) [1]. The different causes of cardiac maladaptive remodeling likely share common molecular, biochemical, and mechanical pathways. Cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, inflammatory cells, coronary vasculature and extracellular matrix all participate in the remodeling events [1, 2].

Here we focus on mast cells (MCs). MC-derived mediators such as histamine, chymase, tryptase, matrix metalloproteinase, tumor necrosis factor, stem cell factor, transforming growth factor and others have pro-inflammatory, pro-hypertrophic, vasoactive and pro-fibrotic effects [3–10]. A set of signaling events induces degranulation of MC [11] and protein kinase C (PKC) is a convergence point for these events [11]. Although in vitro studies implicated PKC in MC degranulation [12, 13], there are no in vivo studies using HF models that examine the role of PKC in MC degranulation and HF pathogenesis.

We have recently reported that hypertension induced by high salt diet results in compensatory hypertrophy and eventually HF in Dahl salt-sensitive rats and εPKC activation has been found to contribute to HF progression [14]. In that study and in the following, we used an εPKC-specific inhibitor peptide (εV1-2 EAVSLKPT) that was designed in our laboratory over 10 years ago [15]. The εPKC-specific inhibitor used by us and independently by others is described in over 150 published studies. The selectivity of εV1-2 for εPKC was confirmed and reported in many of these studies. For example, we demonstrated that εV1-2 selectively inhibits εPKC translocation and εPKC-mediated cardiac contractility whereas the translocation of other isozymes such as δPKC and βPKC is unaffected [15]. We also showed that εV1-2 exerts an opposite effect to that of a selective activator of εPKC and that co-incubation of εV1-2 or chelerythrine, a non-selective εPKC inhibitor, with the selective agonist of εPKC undoes the cardiac protection against ischemic damage [16]. In a more recent report [17], we used four different assays to confirm the effect of several εPKC regulating peptides, including εV1-2. We measured inhibition of εPKC translocation in culture, inhibition of εPKC-mediated MARCKS phosphorylation in cells, lack of the peptide effect on MARCKS phosphorylation in cells from εPKC knockout mice, and inhibition of cardiac protection by pharmacological preconditioning (an εPKC-specific function as determined by multiple laboratories, using a variety of tools including εPKC knockout mice). Similarly, the selectivity of the δPKC inhibitor, δV1-1, was described in numerous studies (e.g. [18, 19]). Therefore, all the peptide regulators used in this study are selective inhibitors of their corresponding isozymes, they do not affect any other isozyme and they do not exert any side effects even when treating animals for a prolonged period [20].

In a recent study we found that sustained inhibition of εPKC by εV1-2 prolonged animal survival, improved heart functions and reduced myocardial fibrosis in hypertensive salt-sensitive Dahl rats [14]. In the present study, we determined the effect of εPKC inhibition on MC activity and number and in the pathogenesis of HF.

2. Methods

2.1. Animal model and treatment protocol

The induction of hypertension and HF has been described in our earlier report [14, 21]. Briefly, 6 week-old male Dahl rats were fed with an 8% NaCl containing (high-salt; DS) diet to induce systemic hypertension, which resulted in concentric left ventricular hypertrophy at the age of 11 weeks, followed by myocardial dilatation and HF at the age of 17 weeks and death by ~21 weeks. DS rats were treated either with TAT conjugated-εV1-2, an εPKC-selective inhibitor peptide, or TAT conjugated-δV1-1, a δPKC-selective inhibitor peptide, from 11 weeks (hypertrophic phase) until 17 weeks (HF phase). Body weight of the high-salt fed DS rats was decreased at 17 weeks in comparison to 11 weeks. The PKC peptide modulators were administered at a dose of 3 mg/Kg/day in a sustained fashion by implanting Alzet mini pumps, as we described before [14, 22]. TAT (1.6 mg/Kg/day) treatment was used as a negative control for these peptides. Treatment with olmesartan (3mg/Kg/day), an angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker (ARB; given by oral gavage daily), a standard drug for HF therapy was used as a positive control. The rats were euthanized at weeks 11 and 17 to assess myocardial histopathology such as vasculopathy, inflammation, hypertrophy, fibrosis, and MC degranulation during disease progression.

2.2. Histopathology

Hearts were fixed with 10% formalin in PBS, embedded in paraffin, and several transverse sections were cut from the mid-ventricles and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H-E) and Masson’s Trichrome. Myocardial fibrosis was observed by the differences in the color (blue fibrotic area opposed to red myocardium) of the photomicrographs of Trichrome stained slides.

H-E stained slides were used to observe infiltration of inflammatory cells in myocardium using a high-power light microscope. Photomicrographs of H-E stained sections from 400X and 650X magnifications were utilized for the quantification of both number of infiltrating inflammatory cells and vessel patency, respectively. Both Masson’s Trichrome and H-E stained slides were used for the observation of coronary vascular thickening and vessel patency.

2.3. MC Staining and Quantitation

Histochemical staining with toluidine blue was performed to identify MCs as described previously [23]. For toluidine blue staining, slides of paraffinized sections of the myocardium were dewaxed, rehydrated and incubated with 0.05% w/v toluidine blue for 30 min followed by counterstaining with 0.01% w/v eosin for 1 min. Metachromatic staining of MC granules was used to identify the status of degranulation. MC density was quantified by counting the number of toluidine blue-positive MCs per field (100 X). At least 20 fields were included from each slide for counting.

2.4. β-hexosaminidase (β-Hex) release assay

Quantification of β-Hex release from isolated MCs is an index of MC degranulation. 10 µl of purified peritoneal MCs was suspended at a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells/ml in Tyrode’s buffer and stimulated with 10 µl of compound 48/80 (1 µg/ml) or PMA (100 nM) (activator of PKC) for one hour in a 96 well V-bottom microplate at 37°C. The cells were pretreated with εV1-2 (10 µM) or δV1-1 (10 µM) for 15 min prior to PMA stimulation. After stimulation, the plate was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min and 10 µl of supernatant was transferred to another flat bottom plate. Another 7–10 µl of supernatant was removed from each well and discarded. Then 20 µl of 0.5% Triton X-100 was added to each pellet and the cells were lysed by repetitive pipetting. 10 µl of this pellet lysate was added to the wells of a flat bottom microplate and 50 µl of p-nitrophenyl-N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidine (p-NAG), a β-Hex substrate, was added to each well containing supernatant and pellet lysate, and further incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Finally, 150 µl of 0.2M glycine was added to stop the reaction and the samples read at 405nm. The results were expressed as percentage release of β-Hex.

2.5. Western immunoblotting of mast cell protease (MCP)-1

Protein lysates were prepared by homogenizing heart tissue in 1 ml of lysis buffer [8 M urea, 7 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.8% triton X-100, 3% 2-mercaptoethanol, 5 µg/ml aprotinin, and 5 µg/ml leupeptin]. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and identified with primary antibody, i.e. anti-MCP-1 goat polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phospho dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH) mouse monoclonal antibody (Advanced Immunochemical Inc, Long Beach, CA). After primary antibody incubation, bound antibody was visualized with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) coupled secondary antibody (Santa Cruz) and chemiluminescence-developing agents. The scanned images of Western blot bands were analysed by Image J software (NIH) for quantification of the band intensity.

2.6. Immunohistochemistry for transforming growth factor (TGF)β1

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cardiac tissue sections were used for immunohistochemical staining. After deparaffinization and hydration, the slides were washed in Tris buffered saline (TBS; 10 mmol/L Tris HCl, 0.85 % NaCl, pH 7.5) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the slides in 0.6 % H2O2/methanol. A pressure cooker method was used to retrieve the antigen. Blocking was done with normal serum. After overnight incubation with polyclonal rabbit TGFβ1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) at 4°C, the slides were washed in TBS and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz) was added and incubated at room temperature for 45 min. The immunostaining was visualized with the use of diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) and counterstained with hematoxylin.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical comparison between groups was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s or Bonferroni’s method.

3. Results

3.1. Disease progression in hypertensive DS rats

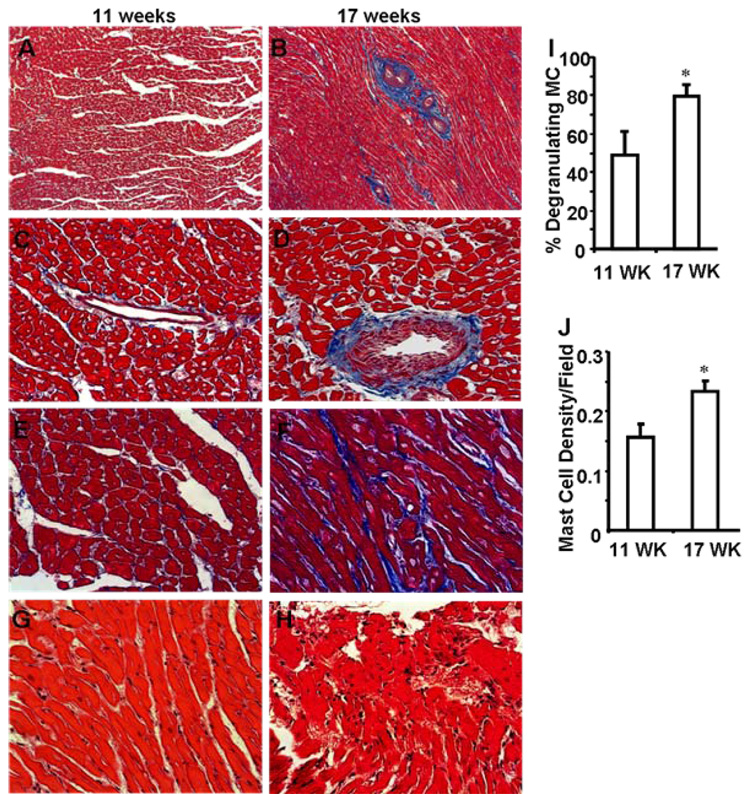

We recently reported that systemic hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive rats increases myocardial perivascular and interstitial fibrosis in comparison to normotensive rats [14]. Here we determined the extent of fibrosis in the hearts with compensated hypertrophy (11 weeks) with that in hearts at the beginning of the decompensated state (at 17 weeks). Myocardial sections of 17 week-old hypertensive rats (HF stage) exhibited extensive fibrosis (Fig. 1B, 1D and 1F) as compared with myocardial sections from 11 week-old hypertensive rats (hypertrophic stage) (Fig. 1A, 1C and 1E). Vasculopathy was more prevalent during the HF stage (Fig. 1B and 1D). We also observed more inflammation during the HF stage as compared with the hypertrophic stage (Fig. 1H vs. 1G). Finally, the percent of degranulated MCs per section (as determined by toluidine blue staining, Fig. 1I) as well as the total number of MCs (Fig. 1J) significantly increased in 17 week-old hypertensive rats as compared with 11 week-old rats.

Fig. 1. Disease progression in high-salt diet Dahl rats from 11 weeks to 17 weeks.

Micrographs showing cardiac fibrosis at 11 weeks (A) and 17 weeks (B) are provided (X100). Perivascular and interstitial fibrosis at 11 weeks and 17 weeks respectively (C, D and E, F). (X400). The myocardial sections were stained with Masson’s Trichrome. Blue color depicts the fibrotic area versus the red-colored normal myocardial region. The extent of coronary vessel patency and intimal thickening (B, D) can be seen at 17 weeks (as indicated by black arrows). Hematoxylin-eosin (H-E) stained tissue from high-salt diet Dahl rats at 11 weeks depict almost no inflammation (G). At 17 weeks, there are more inflammatory cells in the myocardium (H). Magnification of G and H is X400. Representative micrograph from each group are shown. MC degranulation (I) and the number of MCs (J) were increased significantly in 17 week-old hypertensive rat hearts as compared with 11 week-old rat hearts. MCs were counted using toluidine blue-stained myocardial sections.*p < 0.05 vs. 11 weeks; n=3.

3.2. εPKC inhibition reduces MC degranulation in the myocardium of hypertensive DS rats

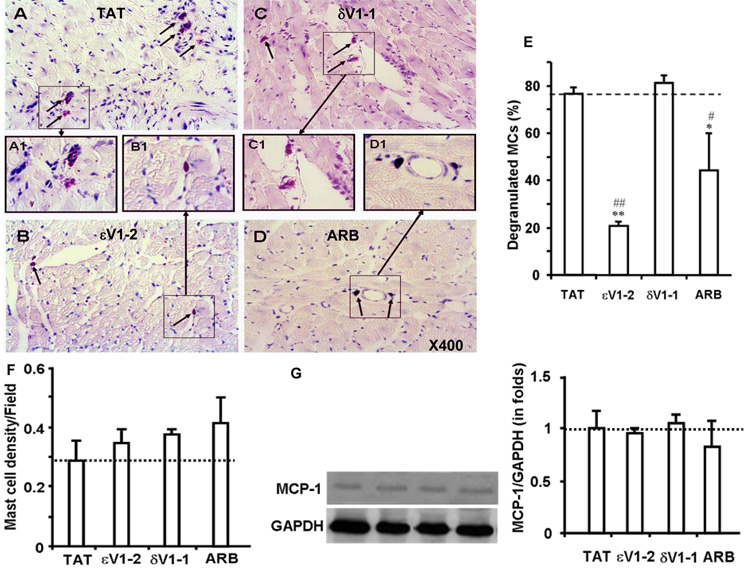

Treatment with the εPKC inhibitor, εV1-2, between weeks 11 and 17 significantly attenuated MC degranulation in the myocardium of the hypertensive rats as compared with TAT-treated hypertensive rats (Fig. 2B vs. 2A). Angiotensin receptor blocker, olmesartan, also reduced MC degranulation in the hearts from hypertensive rats (Fig. 2D), whereas the δPKC inhibitor, δV1-1, had no effect on MC degranulation (Fig. 2C). Quantitation of the data (Fig. 2E) demonstrated that εV1-2 treatment was the most effective in attenuating MC degranulation, as measured in the myocardium of 17 week-old hypertensive rats. The total number of MC in the myocardium (MC density) was not significantly different in the various treated groups relative to the TAT-treated control group (Fig. 2F). Further, none of the treatments attenuated the levels of MCP-1 in the myocardium in comparison to the TAT-treated control group (Fig. 2G). Therefore, our data are consistent with εPKC inhibition affecting MC degranulation rather than MC number in hearts from hypertensive rats.

Fig. 2. Attenuation of MC degranulation in myocardial tissue by εPKC inhibition.

Shown are micrographs of heart sections from 17 week-old hypertensive Dahl rats treated with TAT (A), εV1-2 (B), δV1-1 (C) and ARB (D). Tissue was stained with toluidine blue. Violet color adjacent to darker violet stained cells are degranulating MCs, whereas dark blue-colored cells are MCs that did not discharge recently. TAT (A) and δV1-1 (C) treated myocardial sections show staining patterns that indicate MC degranulation (arrows). Boxed areas in panels A-D are magnified in A1-D1, respectively. Quantification graph of degranulated MCs (E). MCs showing partial or complete degranulation were counted as degranulating MCs. Data are provided as percent of total MCs. Degranulation of MCs decreased in εV1-2 and ARB treated rats, whereas TAT and δV1-1 treatments did not attenuate degranulation. MC density in heart. MC density is calculated by counting both degranulating and non-degranulating MCs and plotted as a graph (F). MCP-1 levels in the myocardium (G). Representative Western blot images of MCP-1 and GAPDH from each group and quantification of the band density from at least 5 different animals from each group are shown. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. TAT treatment; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. δV1-1 treatment. n=3.

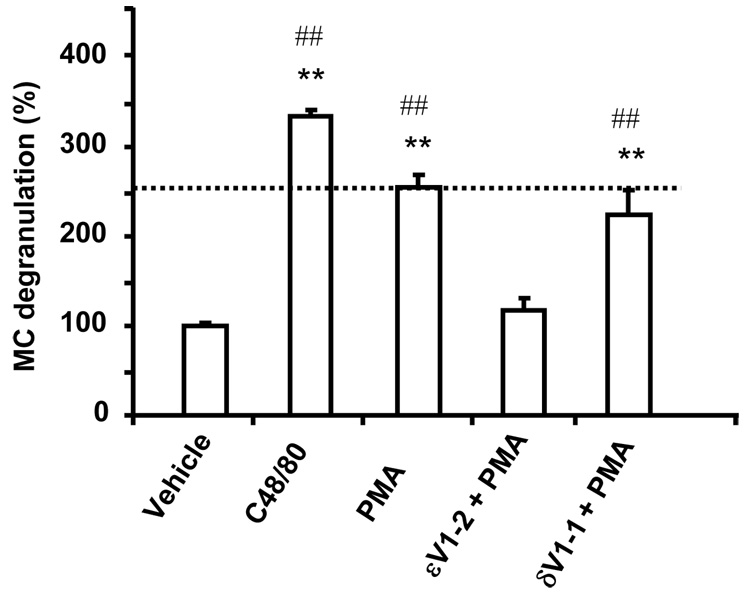

3.3. εPKC inhibition reduces MC degranulation of rat peritoneal MCs, in vitro

Using MC in culture, we next determined whether εPKC inhibition affects MC degranulation by PMA. PMA-induced MC degranulation was similar to that induced by C48/80, a MC secretagogue compound (Fig. 3). PMA-induced MC degranulation (as measured by β-Hex release) was reduced by over 90% with εV1-2 pretreatment whereas δV1-1 pretreatment did not alter PMA-induced MC degranulation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. PMA-induced MC degranulation in isolated rat peritoneal MCs was inhibited by εV1-2 pretreatment.

β-Hex release is considered as an index of MC degranulation. δV1-1 pretreatment did not alter PMA-induced MC degranulation. PMA-induced MC degranulation was comparable to a degranulating agent of MCs, compound 48/80. n=3 to 5. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01 vs. vehicle; ##p < 0.01 vs. εV1-2 + PMA

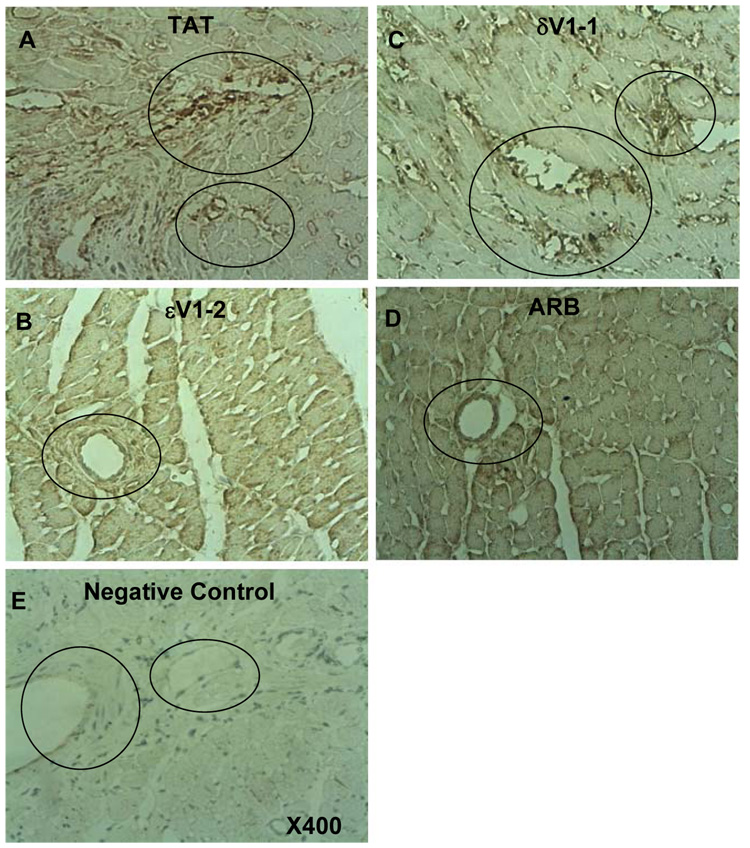

3.4. εPKC inhibition reduces TGFβ1 levels in the myocardium of DS rats with HF

Since MCs secrete pro-fibrotic factors such as TGFβ1 [3, 5–7, 9], using serial sections obtained from the same cardiac samples as above, we next determined the location of MCs relative to fibrotic areas. We observed MCs (toluidine-blue positive cells) nearby the fibrotic regions (Masson’s Trichrome staining; MCs were co-localized to both interstitial and perivascular fibrotic regions (data not shown).

TGFβ1, which stimulates fibroblast proliferation and collagen secretion and deposition [6, 24], is stored in MC granules and is released in active form upon MC stimulation [25]. Using Western blot analysis, we previously found a 2 fold increase in the levels of active TGFβ1 when comparing hypertensive Dahl rats at the age of 17 weeks with normotensive rats and that εPKC inhibition decreases this TGFβ1 increase by 50% [14]. Using immunohistochemistry here, we found that TGFp1 was localized to the perivascular regions (Fig. 4A), especially near small to mid-size vessels with vasculopathy and/or perivascular fibrosis. TGFβ1 co-localized with MCs (data not shown). We confirmed that treatment with εV1-2 (Fig. 4B) reduced TGFβ1 levels in the myocardium relative to TAT or δV1-1 treatments (Fig. 4A and 4C) and that ARB also decreased the myocardial levels of TGFβ1 (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4. Suppression of perivascular localization of TGFβ1 in hypertensive Dahl rats by εPKC inhibition.

Immunohistochemical staining of myocardial TGFβ1 in 17 week-old hypertensive rats treated with TAT (A), εV1-2(B),δV1-1 (C) or ARB (D) (dark brown color): X400. Negative control for the immunostaining (without primary antibody) in the TAT treated animals is provided in E. The perivascular regions (circled areas) show more TGFβ1 staining in samples from TAT or δV1-1 treated animals as compared with εV1-2 -or ARB-treated animals; n=3.

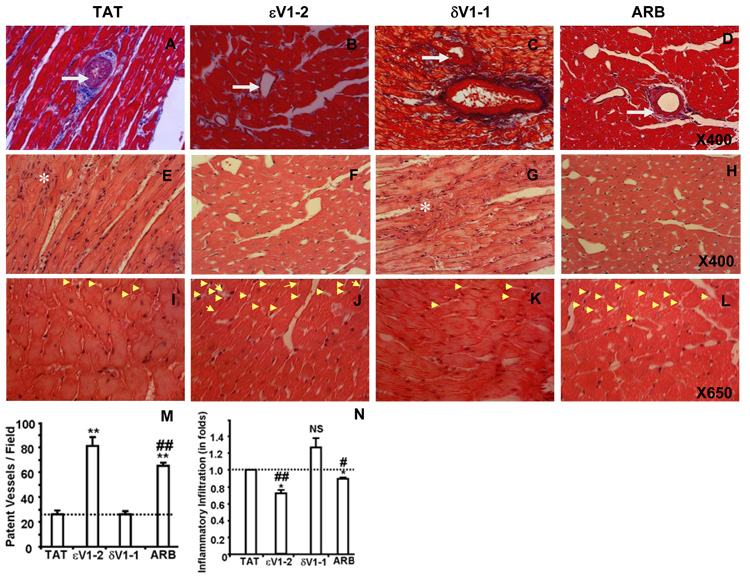

3.5. εPKC inhibition decreases vasculopathy and inflammation in the myocardium of DS rats with HF

We also found that εPKC inhibition with εV1-2 reduced vascular (intimal) thickening (Fig. 5B) relative to TAT- (Fig. 5A) or δV1-1-treatment (Fig. 5C). ARB also decreased the vascular thickening (Fig. 5D). εV1-2 and ARB treatments increased coronary vessel patency (Fig. 5J and 5L) as compared to TAT (Fig. 5I) or δV1-1 treatments (Fig. 5K). There was almost a three fold increase in the number of patent small and medium coronary vessels in animals treated with εV1-2 as compared with those treated with TAT or δV1-1 (Fig. 5M).

Fig. 5. εPKC inhibition causes reduction in coronary vasculopathy and myocardial inflammation in hypertensive rats.

Masson’s Trichrome-stained sections are showing vasculopathy (intimal thickening and patency of medium sized coronary vessels) of hypertensive Dahl rats treated with TAT (A), εV1-2 (B), δV1-1 (C) and ARB (D); X400. The infiltration of inflammatory cells (indicated by asterisks) is shown by hematoxylin-eosin stained myocardial sections of hypertensive Dahl rats treated with TAT (E), εV1-2 (F), δV1-1 (G) and ARB (H); X400. Vessel patency of small coronary vessels is shown by yellow arrow heads of the H-E stained cardiac sections that were treated with TAT (I), εV1-2 (J), δV1-1 (K) and ARB (L). Quantitation of vessel patency (M) and inflammatory cells (N) is provided as graphs. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. TAT treatment; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. δV1-1 treatment. NS-Not statistically significant compared with TAT treatment. n=3.

Treatment with εV1-2 also reduced the number of inflammatory cells in the myocardium (Fig. 5F) relative to TAT (Fig. 5E) or δV1-1 treatments (Fig. 5G). ARB also decreased myocardial inflammation (Fig. 5H). However, quantification of the number of inflammatory cells (Fig. 5N) revealed that sV1-2 treatment reduced these markers of heart pathology more than ARB treatment.

4. Discussion

In the present model, sustained hypertension in salt-sensitive Dahl rats fed a high-salt diet leads to cardiac dysfunction and HF by 17 weeks. Relative to 11 weeks old hypertensive rats, we observed significant pathological cardiac remodeling processes including myocardial fibrosis, vascular intimal thickening, reduction of coronary vessel patency, inflammation and increased cardiac MC number and degranulation. We have recently found that sustained treatment with εV1-2 an εPKC-selective inhibitor [15] from the age of 11 to 17 weeks, improved cardiac function in these rats [14]. Here we show that treatment with εV1-2 during this period attenuated MC degranulation without affecting MC density. This treatment also inhibited infiltration of inflammatory cells, vasculopathy and fibrosis in the myocardium of hypertensive DS rats. In contrast, treatment with δV1-1, a δPKC-specific inhibitor [16, 19] for the same period, did not improve any of these pathological events. Our previous work showed that in vitro collagen secretion is also dependent on εPKC activation [14]. Although, we cannot rule out that some of the benefit of εPKC inhibition is indirect, our data are consistent with a deleterious role for εPKC in cardiac fibrosis.

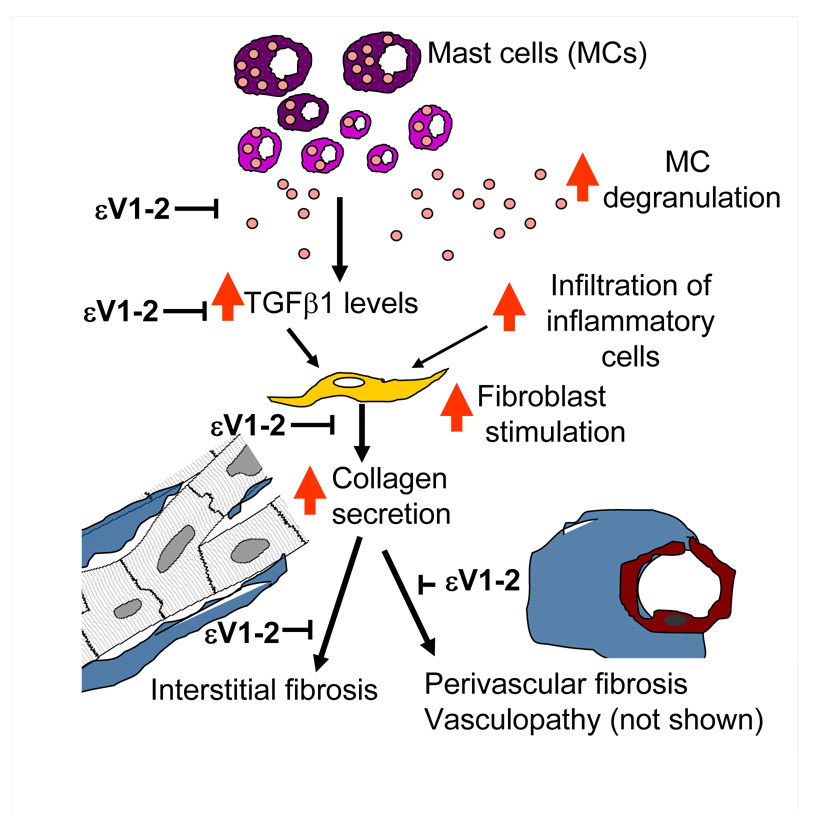

Possible steps in cardiac pathology associated with hypertension that are inhibited by εV1-2 treatment are depicted schematically in Fig. 6. Based on our studies here, we suggests that εV1-2 inhibits MC degranulation, which in turn, decreases TGFβ1 levels, infiltration of inflammatory cells, fibroblast stimulation and intestinal and perivascular fibrosis. ARB also inhibited all these processes, but to a lesser extent as compared with εV1-2. Several other studies suggest a role for MCs in HF progression. The number of degranulated MCs in the infarcted and peri-infarcted regions was found to be higher relative to the non-infarcted region in the hearts of rats [26] and MCs are found in the fibrotic region of the infarcted myocardium in dogs [27]. Further, the number of degranulated MCs in the area surrounding the coronary arteries with ruptured plaques is higher in human subjects [28]. MCs appear to be critical also in remodeling associated with aortocaval fistula-induced HF in rats [29]. Finally, as we stated earlier, MCs have been implicated in postmyocarditis HF, as was found in our earlier studies in rats [7, 30] and by others in mice [31]. Therefore, together with this study in HF of Dahl salt-sensitive rats, it appears that MCs are important component in the pathogenesis of HF irrespective of the etiology.

Fig. 6. A scheme demonstrating how MCs in the myocardium may contribute to remodeling events and the role of εPKC in this process.

Degranulating MCs are increased in the myocardium of hypertensive rats. MC degranulation, in turn, increases TGFβ1 levels (and other MC mediators) and thus promotes infiltration of inflammatory cells into the myocardium. All of this leads to increased perivascular and interstitial fibrosis (proliferation and activation of cardiac fibroblasts as well as secretion of collagen), and vasculopathy (not shown). Our data suggest that all these events are mediated, at least in part, by εPKC activation. The steps in the cascade that were inhibited by εPKC treatment in vivo are indicated in the scheme. However, whether these events are regulated by εPKC directly or indirectly remains to be determined.

MC degranulation products are pro-inflammatory, hypertrophic and pro-fibrogenic in nature. TGFβ1, a cytokine that is released upon MC stimulation, modulates proliferation of fibroblasts and enhances synthesis and deposition of collagen [6, 24, 25]. Histamine, tryptase, chymase, tumor necrosis factor-a and stem cell factor, the MC derived mediators, are also involved in remodeling and inhibition of chymase attenuates adverse cardiac remodeling in different HF models [7, 32]. However, it is not practical to inhibit each mediator of MCs considering the plethora of MC mediators that are released during degranulation. Instead, degranulation of MCs is a convergence point of signaling that leads to cardiac hypertrophy, whose inhibition may provide the desired therapeutic effect. We showed here that inhibition of εPKC correlates with attenuated MC degranulation and thus suggest that such an inhibitor may be useful as a treatment option for heart failure.

A role for PKC in MC activity in the myocardium has not been previously described and conflicting reports on the role of PKC isozymes on MC function in vitro have been reported. For example, εPKC activation was found to induce c-fos and c-jun gene expression in an activated RBL-2H3 MC line [33]. However, εPKC activation inhibited antigen-induced hydrolysis of inositol phospholipids by reducing tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase C in permeabilized RBL-2H3 cells [34]. Another study reported that εPKC plays a redundant role on MC degranulation as the extent of degranulation was not significantly different between bone marrow-derived MCs from εPKC null mice and wild type mice following antigen-induced activation [35]. Similarly, there are conflicting reports which demonstrate positive or negative roles of δPKC on MC degranulation [36, 37]. Heterogeneity of MCs and use of non-selective PKC modulators may explain some of these conflicting reports on the role of PKC in MC degranulation. Further, genetic manipulations of PKC may also contribute to the conflicting reports due to the compensatory effects by other isozymes. For example, δPKC expression increases in hearts of εPKC KO mice by 60% and it is also more activated in these εPKC KO mice relative to wild type mice [38]. Similarly, Ways et al showed that over-expression of αPKC in breast cancer cells increased the expression of βPKC and decreased the expression of δ and ηPKC [39]. Ping and collaborators found that over-expression of εPKC results in its association with the anchoring protein of βPKC, RACK1, instead of its own RACK, RACK2. They also showed that εPKC-induced hypertrophy involved the recruitment of both PKCβII and εPKC by RACK1. Therefore, the combined effect of PKCβII and εPKC (and not the effect of εPKC, alone) may have led to the observed development of cardiac hypertrophy and failure in AE-εPKC-H mice [40, 41] that express high levels of εPKC by doing A-to-E point mutation at the pseudo substrate domain. We suggest that genetic manipulation of this family of isozymes results in compensatory changes in other PKC isozymes, making the interpretation of data difficult.

Hence, we used isozyme-selective pharmacological inhibitors in this study, and we applied them once the disease occurred, thus better mimicking the scenario associated with patients care. We show there a direct role for εPKC in MC degranulation and our data are consistent with a deleterious role of sustained εPKC activation in the pathology of HF in these hypertensive rats [14]. The role of MC degranulation in the progression of myocardial fibrosis of HF in DS rats is further suggested by the co-localization of degranulated MCs in the fibrotic regions (data not shown). Similar association between myocardial fibrosis and MCs are demonstrated in the myocardium of human patients with HF [42]. In the hypertensive rats, administration of εV1-2 resulted in a decrease in interstitial and perivascular fibrosis as evident from Masson’s-Trichrome staining (see also [14]). Further, εV1-2 treatment also decreased TGFβ1 levels in the myocardium of these rats, which in turn may contribute to reduced fibrosis. However, there may be other sources for TGFβ1, including cardiomyocytes and inflammatory cells, and the effect of εPKC on fibrosis may thus be indirect.

Olmesartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker, was used as a positive control for the treatment of HF progression in this study. We administered 3 mg/Kg/day of olmesartan, a concentration that did not affect hypertension per se. Olmesartan treatment also attenuated MC degranulation and inhibited the pathological changes associated with excessive fibrosis. However, εV1-2 appeared to be a more potent MC inhibitor than ARB. In a recent study, we found that εPKC activation was not inhibited by olmesartan in these hypertensive Dahl rats [14]. Therefore, it εV1-2 and ARB may exert their effects via different mechanisms.

In addition to a reduction in myocardial fibrosis, εPKC inhibition attenuated vascular remodeling and infiltration of inflammatory cells. These beneficial effects may also be attributed to the decrease in MC degranulation; as we stated earlier, MC mediators are vasoactive and proinflammatory factors. The observed co-localization of degranulating MCs in the inflammatory milieu and proximity to remodeled vasculature in the samples from TAT or δV1-1 treated samples may indicate the involvement of MCs and their mediators in these processes.

In summary, εPKC inhibition in hypertension-induced HF led to the suppression of pathological remodeling such as myocardial fibrosis, vasculopathy and inflammation that correlated with improvement of myocardial function. We suggest that these beneficial effects of εPKC inhibition on HF progression are, at least in part, due to inhibition of cardiac MC degranulation. Further studies that reveal the time course changes in MC degranulation in HF and the effects of an εPKC inhibitor at these various time points will provide detailed information about the role of εPKC in MC degranulation in HF.

Acknowldgements

We thank Dr. Adrian M. Piliponsky and Prof. Stephan J Galli for their advice. We appreciate Bharathi Murugavel for her assistance in this research work. We thank Dr. Adrienne Gordon for helpful discussions.

This study was supported by National Institute of Health Grant HL076675 to DMR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DM-R is the founder of KAI Pharmaceuticals, Inc, a company that plans to bring PKC regulators to the clinic. However, none of the work in her academic laboratory is supported by the company. Other authors have no disclosure.

Reference

- 1.Opie LH, Commerford PJ, Gersh BJ, Pfeffer MA. Controversies in ventricular remodelling. Lancet. 2006;367:356–367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knecht M, Burkhoff D, Yi GH, Popilskis S, Homma S, Packer M, et al. Coronary endothelial dysfunction precedes heart failure and reduction of coronary reserve in awake dogs. J of Mol and Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:217–227. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordana M, Befus AD, Newhouse MT, Bienenstock J, Gauldie J. Effect of histamine on proliferation of normal human adult lung fibroblasts. Thorax. 1988;43:552–558. doi: 10.1136/thx.43.7.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JK, Tyler CL, Jones CA, Ruoss SJ, Hartmann T, Caughey GH. Tryptase, the dominant secretory granular protein in human mast cells, is a potent mitogen for cultured dog tracheal smooth muscle cells. Am J Resp Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:227–236. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.2.7626290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruoss SJ, Hartmann T, Caughey GH. Mast cell tryptase is a mitogen for cultured fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:493–499. doi: 10.1172/JCI115330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrov VV, Fagard RH, Lijnen PJ. Stimulation of collagen production by transforming growth factor-beta1 during differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. Hypertension. 2002;39:258–263. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palaniyandi SS, Nagai Y, Watanabe K, Ma M, Veeraveedu PT, Prakash P, et al. Chymase inhibition reduces the progression to heart failure after autoimmune myocarditis in rats. Exp Biol Med. 2007t;232:1213–1221. doi: 10.3181/0703-RM-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janicki JS, Brower GL, Gardner JD, Forman MF, Stewart JA, Jr, Murray DB, et al. Cardiac mast cell regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-related ventricular remodeling in chronic pressure or volume overload. Cardiovas Res. 2006;69:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vilcek J, Palombella VJ, Henriksen-DeStefano D, Swenson C, Feinman R, Hirai M, et al. Fibroblast growth enhancing activity of tumor necrosis factor and its relationship to other polypeptide growth factors. J Exp Med. 1986;163:632–643. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.3.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patella V, Marino I, Arbustini E, Lamparter-Schummert B, Verga L, Adt M, et al. Stem cell factor in mast cells and increased mast cell density in idiopathic and ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1998;97:971–978. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilfillan AM, Tkaczyk C. Integrated signalling pathways for mast-cell activation. Nature Reviews. 2006;6:218–230. doi: 10.1038/nri1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang EY, Szallasi Z, Acs P, Raizada V, Wolfe PC, Fewtrell C, et al. Functional effects of overexpression of protein kinase C-alpha, -beta, -delta, -epsilon, and -eta in the mast cell line RBL-2H3. J Immunol. 1997;159:2624–2632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludowyke RI, Elgundi Z, Kranenburg T, Stehn JR, Schmitz-Peiffer C, Hughes WE, et al. Phosphorylation of nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA on Ser1917 is mediated by protein kinase C beta II and coincides with the onset of stimulated degranulation of RBL-2H3 mast cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:1492–1499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inagaki K, Koyanagi T, Berry NC, Sun L, Mochly-Rosen D. Pharmacological Inhibition of {epsilon}-Protein Kinase C Attenuates Cardiac Fibrosis and Dysfunction in Hypertension-Induced Heart Failure. Hypertension. 2008 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.109637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JA, Gray MO, Chen CH, Mochly-Rosen D. A protein kinase C translocation inhibitor as an isozyme-selective antagonist of cardiac function. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24962–24966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorn GW, 2nd, Souroujon MC, Liron T, Chen CH, Gray MO, Zhou HZ, et al. Sustained in vivo cardiac protection by a rationally designed peptide that causes epsilon protein kinase C translocation. PNAS. 1999;96:12798–12803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandman R, Disatnik MH, Churchill E, Mochly-Rosen D. Peptides derived from the C2 domain of protein kinase C epsilon (epsilon PKC) modulate epsilon PKC activity and identify potential protein-protein interaction surfaces. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4113–4123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608521200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Hahn H, Wu G, Chen CH, Liron T, Schechtman D, et al. Opposing cardioprotective actions and parallel hypertrophic effects of delta PKC and epsilon PKC. PNAS. 2001;98:11114–11119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191369098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi X, Inagaki K, Sobel RA, Mochly-Rosen D. Sustained pharmacological inhibition of deltaPKC protects against hypertensive encephalopathy through prevention of blood-brain barrier breakdown in rats. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:173–182. doi: 10.1172/JCI32636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begley R, Liron T, Baryza J, Mochly-Rosen D. Biodistribution of intracellularly acting peptides conjugated reversibly to Tat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:949–954. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inagaki K, Iwanaga Y, Sarai N, Onozawa Y, Takenaka H, Mochly-Rosen D, et al. Tissue angiotensin II during progression or ventricular hypertrophy to heart failure in hypertensive rats; differential effects on PKC epsilon and PKC beta. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1377–1385. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inagaki K, Begley R, Ikeno F, Mochly-Rosen D. Cardioprotection by epsilon-protein kinase C activation from ischemia: continuous delivery and antiarrhythmic effect of an epsilon-protein kinase C-activating peptide. Circulation. 2005;111:44–50. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151614.22282.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palaniyandi SS, Watanabe K, Ma M, Tachikawa H, Kodama M, Aizawa Y. Inhibition of mast cells by interleukin-10 gene transfer contributes to protection against acute myocarditis in rats. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3508–3515. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eghbali M, Tomek R, Sukhatme VP, Woods C, Bhambi B. Differential effects of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and phorbol myristate acetate on cardiac fibroblasts. Regulation of fibrillar collagen mRNAs and expression of early transcription factors. Circ Res. 1991;69:483–490. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.2.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindstedt KA, Wang Y, Shiota N, Saarinen J, Hyytiainen M, Kokkonen JO, et al. Activation of paracrine TGF-beta1 signaling upon stimulation and degranulation of rat serosal mast cells: a novel function for chymase. FASEB J. 2001;15:1377–1388. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0273com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engels W, Reiters PH, Daemen MJ, Smits JF, van der Vusse GJ. Transmural changes in mast cell density in rat heart after infarct induction in vivo. J of Pathol. 1995;177:423–429. doi: 10.1002/path.1711770414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frangogiannis NG, Perrard JL, Mendoza LH, Burns AR, Lindsey ML, Ballantyne CM, et al. Stem cell factor induction is associated with mast cell accumulation after canine myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation. 1998;98:687–698. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.7.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindstedt KA, Mayranpaa MI, Kovanen PT. Mast cells in vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques--a view to a kill. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:739–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brower GL, Chancey AL, Thanigaraj S, Matsubara BB, Janicki JS. Cause and effect relationship between myocardial mast cell number and matrix metalloproteinase activity. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:H518–H525. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00218.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palaniyandi Selvaraj S, Watanabe K, Ma M, Tachikawa H, Kodama M, Aizawa Y. Involvement of mast cells in the development of fibrosis in rats with postmyocarditis dilated cardiomyopathy. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:2128–2132. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fairweather D, Frisancho-Kiss S, Yusung SA, Barrett MA, Davis SE, Gatewood SJ, et al. Interferon-gamma protects against chronic viral myocarditis by reducing mast cell degranulation, fibrosis, and the profibrotic cytokines transforming growth factor-beta 1, interleukin-1 beta, and interleukin-4 in the heart. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1883–1894. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63241-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumoto T, Wada A, Tsutamoto T, Ohnishi M, Isono T, Kinoshita M. Chymase inhibition prevents cardiac fibrosis and improves diastolic dysfunction in the progression of heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:2555–2558. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074041.81728.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Razin E, Szallasi Z, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Rivera J. Protein kinases C-beta and C-epsilon link the mast cell high-affinity receptor for IgE to the expression of c-fos and c-jun. PNAS. 1994;91:7722–7726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozawa K, Yamada K, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Beaven MA. Different isozymes of protein kinase C mediate feedback inhibition of phospholipase C and stimulatory signals for exocytosis in rat RBL-2H3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2280–2283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lessmann E, Leitges M, Huber M. A redundant role for PKC-epsilon in mast cell signaling and effector function. Inter Immunol. 2006;18:767–773. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho SH, Woo CH, Yoon SB, Kim JH. Protein kinase Cdelta functions downstream of Ca2+ mobilization in FcepsilonRI signaling to degranulation in mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leitges M, Gimborn K, Elis W, Kalesnikoff J, Hughes MR, Krystal G, et al. Protein kinase C-delta is a negative regulator of antigen-induced mast cell degranulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3970–3980. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.3970-3980.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gray MO, Zhou HZ, Schafhalter-Zoppoth I, Zhu P, Mochly-Rosen D, Messing RO. Preservation of base-line hemodynamic function and loss of inducible cardioprotection in adult mice lacking protein kinase C epsilon. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3596–3604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311459200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ways DK, Kukoly CA, deVente J, Hooker JL, Bryant WO, Posekany KJ, et al. MCF-7 breast cancer cells transfected with protein kinase C-alpha exhibit altered expression of other protein kinase C isoforms and display a more aggressive neoplastic phenotype. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1906–1915. doi: 10.1172/JCI117872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pass JM, Gao J, Jones WK, Wead WB, Wu X, Zhang J, et al. Enhanced PKC beta II translocation and PKC beta II-RACK1 interactions in PKC epsilon-induced heart failure: a role for RACK1. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:H2500–H2510. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pass JM, Zheng Y, Wead WB, Zhang J, Li RC, Bolli R, et al. PKCepsilon activation induces dichotomous cardiac phenotypes and modulates PKCepsilon-RACK interactions and RACK expression. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:H946–H955. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Batlle M, Perez-Villa F, Lazaro A, Garcia-Pras E, Ramirez J, Ortiz J, et al. Correlation between mast cell density and myocardial fibrosis in congestive heart failure patients. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:2347–2349. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]