Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Several therapies have been demonstrated to be beneficial in the management of acute variceal bleeding (AVB). The aim of the present study was to characterize the use of these therapies at a Canadian tertiary care centre.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

A comprehensive chart review was performed to assess the management of all adult cirrhotic patients with AVB who were admitted to a university-affiliated, tertiary care centre between April 2001 and March 2004.

RESULTS:

A total of 81 AVB patients were identified with a mean age of 53.7±13.2 years and a median model for end-stage liver disease score of 14. Endoscopy was performed within 8.2±7.6 h of admission. Variceal banding was performed for 87% of patients with esophageal varices, which were the most common source of bleeding (80%). Octreotide was used in 82% of patients for a mean duration of 74.3±35.4 h; prophylactic antibiotics were used in 25% of patients and beta-blockers were used in 24% of patients without any contraindications. Follow-up endoscopy was arranged for 46 of 71 (65%) survivors. Prophylactic antibiotic use was associated with the presence of ascites, while beta-blockers were used more often in the last year of the study.

CONCLUSIONS:

There is a disconnection between the use of evidence-based recommendations and routine clinical practices in the management of AVB. Deficiencies identified include the lack of use of prophylactic antibiotics and beta-blockers, variable use of octreotide and inadequate follow-up recommendations. There is a need to identify measures to improve the process of care for patients with AVB which would ensure optimal management of these patients.

Keywords: Antibiotic prophylaxis, Beta-blockers, Clinical practice, Secondary prophylaxis, Variceal bleeding

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Plusieurs traitements se sont révélés bénéfiques pour la prise en charge de l’hémorragie variqueuse aiguë (HVA). Le but de la présente étude était de déterminer l’emploi de ces traitements dans un centre de soins tertiaires canadien.

PATIENTS ET MÉTHODE :

Une analyse complète des dossiers a été effectuée afin de vérifier quelle a été la prise en charge des patients cirrhotiques adultes souffrant d’HVA admis dans un centre universitaire de soins tertiaires entre avril 2001 et mars 2004.

RÉSULTATS :

En tout, 81 patients atteints de HVA ont été identifiés. Ils étaient en moyenne âgés de 53,7 ± 13,2 ans et présentaient un modèle médian d’indice de maladie hépatique terminale de 14. L’endoscopie a été pratiquée dans les 8,2 ± 7,6 h suivant l’admission. Un traitement du saignement variqueux a été appliqué chez 87 % des patients qui présentaient des varices œsophagiennes, source principale de l’hémorragie (80 %). De l’octréotide a été administré à 82 % des patients pendant une durée moyenne de 74,3 ± 35,4 h, une antibioprophylaxie a été administrée à 25 % des patients et des bêta-bloquants à 24 % de ceux qui ne présentaient pas de contre-indications. L’endoscopie de suivi a été planifiée chez 46 des 71 survivants (65 %). L’antibioprophylaxie a été associée à la présence d’ascite, tandis que les bêta-bloquants étaient utilisés davantage au cours de la dernière année de l’étude.

CONCLUSION :

On constate un écart entre les recommandations fondées sur des preuves et la pratique clinique lors de la prise en charge concrète de l’HVA. Les lacunes identifiées sont : le recours insuffisant à l’antibioprophylaxie et aux bêta-bloquants, l’utilisation variable de l’oc-tréotide et un suivi inadéquat. Des mesures s’imposent pour ajuster les soins dispensés aux patients souffrant d’HVA de manière à optimiser globalement leur prise en charge.

Acute variceal bleeding (AVB) is one of the most serious and life-threatening complications of cirrhosis. Traditionally, the mortality rate associated with each episode of AVB was reported as being approximately 30% to 60% but several studies (1–7) have shown that the mortality rate secondary to variceal hemorrhage has dropped to approximately 15% to 20%. The improvement in outcomes after an episode of AVB is likely related to several recent additions to the therapeutic armamentarium which include resuscitative, endoscopic, adjunctive pharmacological and radiological therapies (3,4,6). Early endoscopic hemostasis accompanied by concomitant use of vasoactive agents and prophylactic antibiotics, followed by endoscopic eradication of varices and use of nonselective beta-blockers, have been individually shown to improve the outcomes for patients with AVB. There are also several practice guidelines that outline the appropriate care for persons presenting with AVB, which consist of prompt endoscopic hemostasis, concomitant use of vasoactive agents and antimicrobial prophylaxis, and subsequent endoscopic eradication of esophageal varices along with the use of nonselective beta-blockers (8–13). However, there are limited data to characterize the adherence of clinicians to these recommendations and advances in the management of AVB.

Therefore, we sought to analyze the process of care for patients presenting with AVB at a Canadian tertiary care centre and identify whether currently accepted standards of care were being met.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective chart review was performed to identify all adult patients admitted to a university-affiliated, tertiary care centre between April 2001 and March 2004 with the primary diagnosis consistent with AVB. The study was conducted at the Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre, which is a tertiary care, university-affiliated hospital located in Winnipeg, Manitoba, that serves a catchment population of approximately 1.5 million persons.

Search strategy

All charts for persons admitted with a primary diagnosis of cirrhosis, chronic or alcoholic liver disease, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, esophageal varices or varices of other sites as identified by the International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes (Table 1) were reviewed. After reviewing the charts of all cirrhotic patients hospitalized between April 2001 and March 2002, it was discovered that episodes of variceal bleeding could be identified with high sensitivity by limiting the search strategy to the ICD-9 codes for esophageal varices and ‘varices of other sites’ (ICD-9 codes 456.0, 456.1, 456.2x and 456.8). Therefore, it was decided to limit the chart review for subsequent years, that is, after March 2002, to these specific ICD-9 codes.

TABLE 1.

The International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes used for year 1 to identify patients with cirrhosis and varices, and to develop and validate the search strategy for years 2 and 3

| ICD-9 code | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| 456.0 | Esophageal varices with bleeding |

| 456.1 | Esophageal varices without mention of bleeding |

| 456.2x | Esophageal varices in diseases classified elsewhere |

| 456.8 | Varices of other sites |

| 530.82 | Esophageal hemorrhage |

| 535.3 | Alcoholic gastritis |

| 571.0 | Alcoholic fatty liver |

| 571.1 | Acute alcoholic hepatitis |

| 571.2 | Alcoholic cirrhosis of liver |

| 571.3 | Alcoholic liver damage, unspecified |

| 571.41 | Chronic persistent hepatitis |

| 571.49 | Other chronic liver hepatitis |

| 571.5 | Cirrhosis of liver, without mention of alcohol |

| 571.6 | Biliary cirrhosis |

| 571.8 | Other chronic nonalcoholic liver disease |

| 571.9 | Unspecified chronic liver disease |

| 572.3 | Portal hypertension |

| 784.8 | Hemorrhage from throat |

Data abstraction

Data were abstracted on patient demographics, marital status, current living situation, ongoing alcohol use, etiology of cirrhosis and results of pertinent laboratory studies on admission. Information was also collected on the endoscopy performed, specifically, the time between initial presentation and performance of endoscopy, the endoscopic diagnosis and the type of therapeutic modality used, if any. The use of intravenous octreotide, prophylactic antibiotics and beta blockade was tracked, as well as the physician’s recommendations regarding medical care following discharge. If a single patient had multiple hospital admissions for the treatment of AVB, data were extracted only on the initial episode.

Data analysis

The utilization of various endoscopic therapies, including endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL), sclerotherapy or injection of cyanoacrylate glue, was determined. The lag time between the time of initial presentation to hospital and performance of endoscopy was calculated, as was the proportion of patients who received endoscopic assessment within 24 h of presentation. The prevalence of various pharmacological interventions, including the use of octreotide, prophylactic antibiotics and nonselective beta-blockers in patients without a known contraindication to beta blockade, including reactive airway disease or known bradyarrhythmia, was determined.

The severity of underlying liver disease was determined by calculating each patient’s model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score. The outcomes were determined in terms of duration of hospitalization, in-hospital mortality, as well as the rates of rebleeding and mortality within six months of the index episode of variceal bleeding.

NCSS 2004 (Number Cruncher Statistical Systems, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Means and SDs were calculated for normally distributed variables, whereas medians and ranges were computed for non-normally distributed continuous data. χ2 test was used to assess for statistical significance when categorical variables were compared, while Student’s t test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used to assess the significance of comparisons made between normally and non-normally distributed continuous data, respectively. Univariate and stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the predictive factors for the use of prophylactic antibiotics, octreotide infusion and secondary prophylactic beta blockade.

RESULTS

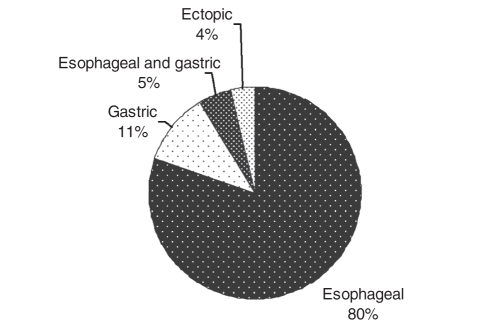

There were 81 patients who were admitted with AVB between April 2001 and March 2004, 65 (80%) of whom bled from esophageal varices, nine (11%) from gastric varices, four (5%) from both esophageal and gastric varices, and three (4%) from ectopic varices (Figure 1). Twenty-eight per cent of patients with AVB were admitted to a monitored bed. Demographic data for AVB patients did not differ from cirrhotic patients admitted for other indications (Table 2). Other common indications for admission of patients with cirrhosis (with or without AVB) are provided in Table 3.

Figure 1).

Sites of bleeding varices

TABLE 2.

Demographics for cirrhosis patients admitted with and without acute variceal bleeding (AVB) between April 2001 and March 2002

| Characteristics | With AVB, n=81 | Without AVB, n=143 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 53.1±13.3 | 55.0±13.7 |

| Men, % | 47 | 54 |

| Etiology, % | ||

| Alcohol | 54 | 54 |

| Viral hepatitis | 9 | 12 |

| Viral and alcohol | 11 | 10 |

| Autoimmune | 14 | 14 |

| MELD score, median (range) | 14 (6–35) | 13 (6–34) |

MELD Model for end-stage liver disease

TABLE 3.

The most responsible diagnosis for admission among 171 patients with 213 admissions between April 2001 and March 2002*

| Diagnosis | Admissions, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Acute variceal bleeding | 30 (14) |

| Nonportal hypertensive-related upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 30 (14) |

| Ascites and complications of ascites | 46 (22) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 49 (23) |

| Infections (excluding SBP)† | 53 (25) |

| Alcoholic withdrawal or seizures | 13 (6) |

| Others | 40 (19) |

Some of the patients had more than one most responsible diagnosis, as determined on the chart review;

Most common infections were pneumonia, skin infections and sepsis with primary site of infection not identified. SBP Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Patient information concerning their social support and social habits were available for 76 (94%) patients, 32% of whom lived alone and 56% of whom had ongoing alcohol use at the time of presentation.

Endoscopy for AVB

The mean time from initial presentation to hospital until performance of endoscopy was 8.2±7.6 h. Fifty-eight per cent of patients had endoscopy performed within 6 h and 97% within 24 h. The majority of patients with esophageal varices underwent EVL as the primary hemostasis modality, whereas cyanoacrylate glue was primarily used for patients with bleeding gastric varices (Table 4). Gastroenterologists performed endoscopy on 67% (n=54) of AVB patients, with the remainder being performed by general surgeons.

TABLE 4.

Hemostasis modality (alone or in combination) used to control acute variceal bleeding

| Hemostasis modality | Patients, % |

|---|---|

| Endoscopic variceal ligation | 74 (87% of patients with esophageal variceal bleeding) |

| Cyanoacrylate glue injection | 15 (85% of patients with gastric variceal bleeding) |

| Endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy | 11 |

| Octreotide alone | 7 |

| Sengstaken Blakemore tube | 1 |

Use of pharmacological therapies

Octreotide:

Octreotide was administered to 66 (82%) patients with AVB, 46 (70%) of whom received it before endoscopy. The mean duration of use of octreotide was 74.3±35.4 h. Univariate analysis did not identify a subgroup of patients who were more likely to receive octreotide.

Prophylactic antibiotics:

Of 81 AVB patients, 20 (25%) either were previously using antibiotics for prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, or were prescribed antibiotics on admission for a suspected or documented infection. Of the remaining 61 subjects eligible for antibiotic prophylaxis, 25% received appropriate treatment with either a fluoroquinolone or a third-generation cephalosporin. The prevalence of antibiotic use was significantly higher among patients with documented (clinical and/or radiological) ascites on admission versus those without ascites (57% versus 6% respectively, P<0.001). Gastroenterologists were significantly more likely to recommend prophylactic antibiotics to AVB patients than were general surgeons (34% versus 9% respectively, P<0.001). Furthermore, patients receiving prophylactic antibiotics had more severe underlying liver disease by MELD score than those who were not offered antibiotic prophylaxis (median MELD score 17 versus 14 respectively, P=0.04).

In multivariate analysis, the only variable that remained significant in predicting the use of prophylactic antibiotics was the presence of ascites (OR 22, 95% CI 4.3 to 114.8, P<0.001).

Beta-blocker prophylaxis:

Sixty-six of 71 patients alive at the time of discharge did not have contraindications to beta-blockade, 16 (24%) of whom were discharged on a nonselective beta-blocker (nadolol or propranolol). In univariate analysis, the lower the MELD score and the more recent the year in which care was provided, the more likely it was that patients would receive prophylactic beta-blockers (OR 1.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.4, P=0.03 and OR 4.6, 95% CI 1.4 to 14.9, P=0.01, respectively). Patient age, etiology of cirrhosis, specialty of the initial consultant (gastroenterology versus general surgery), socioeconomic variables such as presence or absence of social support, smoking status, ongoing alcohol use and presence of comorbidities such as diabetes or congestive heart failure, were not predictive of a patient having received beta-blockers. Additionally, beta-blockers were as likely to be prescribed to individuals who had arrangements made for a subsequent follow-up endoscopy after the initial hemostasis compared with individuals without arrangements for a follow-up endoscopy. In the multivariate analysis, the only factor that remained predictive of beta-blocker use was having received care in a more recent year.

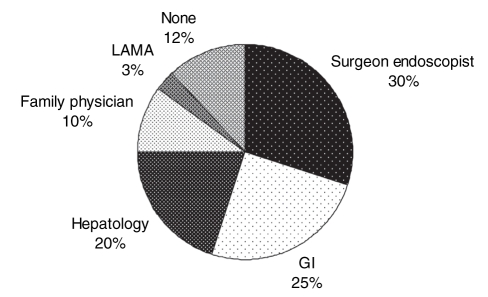

Recommendations for postdischarge care

Recommendations for a follow-up endoscopy were made for 46 (65%) of 71 patients who survived the index hospitalization. A follow-up on discharge for the ongoing care of portal hypertension was arranged for 45% of patients with a gastroenterologist or a hepatologist (Figure 2).

Figure 2).

Specialty of the physician with whom the patients were asked to follow up at discharge for the care of portal hypertension. GI Gastroenterology; LAMA Left against medical advice

Specialty of the initial consultant and the care provided

Gastroenterologists were the initial consultants and performed the initial endoscopy for 67% (n=54) of the patients; general surgeons performed endoscopy for all other patients. Gastroenterologists were more likely than general surgeons to recommend the use of prophylactic antibiotics (34% versus 9%, P<0.001). However, the specialty of the initial consultant did not have significant influence on the rate of octreotide or secondary beta-blocker use, or on the arrangements for follow-up care.

Outcomes

Hemostasis was achieved in 93% of endoscopies, and 71 (88%) patients did not have evidence of rebleeding in the first 72 h after performance of endoscopy. Ten (12%) patients died during the index hospitalization. Older patients and patients with more advanced liver disease with a higher MELD score had a higher in-hospital mortality (P=0.05 and P<0.001, respectively). The median length of hospital stay for patients admitted for AVB was six days (range one to 66 days).

Of 71 patients who were discharged from the hospital following their index episode of AVB, 25 (35%) patients were readmitted for recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding within six months. There were seven more confirmed deaths within six months of hospital discharge among the 71 survivors of the initial episode of variceal bleeding. Therefore, the overall mortality rate at six months for patients presenting with AVB was 21% (17 of 81 patient deaths). Regression analysis failed to detect predictive factors for the outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Current guidelines concerning the care of patients presenting with signs and symptoms of AVB suggest that appropriate management consists of performance of early endoscopy with endoscopic hemostasis as indicated, use of adjuvant pharmacological agents including octreotide, beta-blockers and prophylactic antibiotics, and ensuring the proper arrangement of postdischarge assessment to verify the response to ongoing therapy and to determine the requirements for performance of follow-up endoscopic therapies (8–13). Our study suggested that while endoscopy and endoscopic hemostasis were being performed in a timely fashion in patients with AVB, there remained substantial deficiencies in both the use of essential nonendoscopic adjuvant therapies and the arrangement of postdischarge medical care.

While numerous therapeutic modalities were previously used for the performance of endoscopic hemostasis of acutely bleeding esophageal varices, current data suggest that EVL is the preferred technique, and should be followed by a continuous infusion of intravenous octreotide (8,11,14–16). The use of EVL is associated with lower rates of recurrent bleeding when compared with endoscopic sclerotherapy, and has a decreased risk of serious complications (16). The addition of octreotide to endoscopic therapies is also associated with further decreases in the rebleeding rate (14). Although we demonstrated that EVL was used appropriately in the majority of patients, 20% of patients did not receive adjunctive octreotide. Low rates of concomitant vasoactive drug use (52.6% octreotide and 9.6% vasopressin) were also found in a recent American survey (5). These rates compared poorly with those from a recent practice review in a French study (6), where 90% of subjects received adjunctive vasoactive therapy. Given the favourable side effect profile of octreotide, there are few reasons which justify its underutilization in our population.

Multiple studies and meta-analyses of published data (17–20) have confirmed that providing prophylactic antibiotics to AVB patients decreases both the risk of recurrent bleeding as well as the overall mortality rate. Because antibiotics are generally well-tolerated, they should have been provided to the overwhelming majority of our study patients. Unfortunately, approximately three-quarters of the eligible patients did not receive an appropriate course of prophylactic antibiotics. Our data mirror the findings of a study (21) performed at another Canadian centre, that also reported similarly low rates of antibiotic use. Although higher rates of prophylactic antibiotic use have been reported in American and French studies (3,6), where antibiotic use rates were 47% and 94%, respectively, use in less than one-half of the patients in the American study should be considered unsatisfactory. The higher rate of use of prophylactic antibiotics in the French study was likely related to all of the admissions and patient care being provided in a dedicated liver care unit.

We determined that prophylactic antibiotics were more likely to be used in patients with ascites and in those who were assessed by a gastroenterologist as opposed to a general surgeon. While antibiotics are often indicated in patients with ascites because of suspicion of, or to prevent, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, other serious bacterial infections including urinary tract infections, pneumonias and bacteremic episodes, frequently occur in patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal bleeding and are associated with an increased risk of rebleeding and mortality (18). We believe that there is a need to improve clinician awareness about the dangers of intercurrent infections and the need for prophylactic antibiotics in cirrhotic patients with AVB.

The addition of beta-blockers to the performance of EVL is effective for reducing the risk of recurrent AVB, and is therefore recommended for all patients, without contraindications to their use, undergoing variceal eradication with EVL once they are hemodynamically stable (12,22,23). Unfortunately, we determined that only 24% of eligible subjects were discharged on beta-blockers, which was lower than the 46% to 81% rate of use described in the recent American and French studies (3,5,6). However, we did find that the prevalence of beta-blocker use increased in recent years (4% in year 1, 27% in year 2 and 45% in year 3 of the study). This is likely because the studies demonstrating the efficacy of adjunctive beta-blockers in patients undergoing EVL have been published only recently in the full form (23).

The arrangement of postdischarge medical care is also of paramount importance to fully realize the benefits of any endoscopic or pharmacological therapies which may have been initiated in the hospital. Most patients who undergo EVL for secondary prevention of AVB require multiple courses of endoscopic hemostasis to completely obliterate the culprit varices (16). If follow-up endoscopy is not performed after the performance of initial endoscopic hemostasis, the risk of recurrent AVB remains elevated, and may be as high as 60% to 80% over the following two years (2,24,25). Furthermore, patients who use beta-blockers require medical follow-up to assess patient compliance and to ensure users have had a satisfactory hemodynamic response. However, appropriate follow-up to manage portal hypertension and other complications of cirrhosis was arranged in only a minority of the patients in our study. This may reflect as an uncoordinated discharge planning mechanism for these patients in a busy tertiary care centre. It is also possible that we may have failed to capture the arrangement of postdischarge medical care if it was not explicitly written in the discharge summary.

Despite recent improvements in outcomes, variceal bleeding remains a highly fatal condition. Recent improvements in the outcomes of patients admitted with AVB are likely related to improvements in the various aspects of the process of care, including endoscopic and pharmacological therapies. It is disconcerting that strategies which have been proven to decrease mortality and morbidity are still underused at our centre. We believe that there are many possible explanations for the underutilization of these proven strategies. First, our centre does not use an organized care plan for subjects admitted with AVB. Therefore, there are no mechanisms to remind providers to perform all the necessary steps required to ensure the highest level of care for AVB patients. This likely explains why nongastroenterologists, who may be less likely to know all the components of quality care for AVB patients, are less likely to provide prophylactic antibiotics. Medical care plans have been shown to reduce the variation in the care provided, facilitate expected outcomes, reduce delays and reduce length of stay, and improve cost-effectiveness in the management of numerous other acute medical illnesses including acute myocardial infarction and nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding (26,27). Second, there are currently no published guidelines for the care of Canadian patients with AVB. Another Canadian study (21) also demonstrated low levels of prophylactic antibiotic use, suggesting that the deficiencies observed at our centre may exist nationwide. Guidelines have been proven to increase awareness regarding the proper management of a given condition, and the development of Canadian guidelines could lead to improvement in the care of AVB patients (28). Even though there are several guidelines from the United States national gastroenterology and endoscopy societies, there is a need for wider dissemination of existing guidelines as demonstrated by the limited use of appropriate care in several American studies (3,5,10,12). Establishment of dedicated liver care units or perhaps gastrointestinal bleeding units may further improve the process of care for patients with AVB, as suggested by the near-universal use of recommended care in the French study (6).

We would like to emphasize that gastroenterologists, hepatologists and endoscopists can be easily and rapidly accessed at our centre. Hence, there is ample opportunity to access experts in the practice of managing AVB. Yet we have still identified inadequacies in the management of AVB and suspect that these are common in other major centres that do not standardize management of this clinical problem. We believe that all hospitals should consider managing patients with AVB by establishing routine care maps so that each of the management steps that could improve outcomes in AVB is addressed.

One of the strengths of the methods in our study is the determination of the most comprehensive search strategy (ICD-9 codes) necessary for retrospectively identifying most patients with AVB. On the basis of chart reviews from the first year of the study, we were able to determine that by restricting the strategy to the specific ICD-9 codes for esophageal varices and varices of other sites (ICD-9 codes 456.0, 456.1, 456.2x and 456.8), we could still identify all patients with AVB. However, we would have missed some of the patients with AVB if we had not used all of the specific ICD-9 codes for esophageal varices and varices of other sites. Some of the other studies (4,21,29) have used limited search strategies and could have missed some of the patients admitted with AVB. It is unknown whether, although possible that, the lack of use of multiple discharge codes in retrospectively identifying patients with AVB may result in missing specific subpopulations of patients with AVB who may be managed differently and may have different clinical outcomes than those identified using the ICD-9 code, or ICD-10 code that is specific for bleeding esophageal varices.

Beyond the retrospective design, other limitations of our study include the computation of the six-month rebleeding and mortality rates based on readmissions to our centre because some of the patients may have been readmitted and/or died at another hospital. Therefore, we may have underestimated the true rebleeding and mortality rates for subjects in our study. However, most of the patients with AVB in Manitoba are ultimately transferred to our study centre, which is the largest tertiary care hospital in the province. Another limitation of our study is the evaluation of a single centre experience, which therefore has perhaps limited generalizability to other centres. However, low rates of beta-blocker and prophylactic antibiotic use were also found in the only other published Canadian study (21,29).

CONCLUSIONS

Although there exist strategies that are proven effective to improve the outcome of patients with AVB, the uptake of these practices with the exception of performance of initial endoscopic hemostasis has been limited. Several deficiencies were identified in our study, most notably the low use of both prophylactic antibiotics and beta-blockers, and suboptimal arrangement of postdischarge care. Measures to improve the process of care provided to patients with AVB need to be developed to ensure that the highest quality of care is offered to these patients.

Footnotes

The current study was presented in part at the Digestive Disease Week, Chicago, USA, on May 15, 2005, and the World Congress of Gastroenterology, Montreal, Quebec, on September 14, 2005.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pinto HC, Abrantes A, Esteves AV, Almeida H, Correia JP. Long-term prognosis of patients with cirrhosis of the liver and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1239–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham DY, Smith JL. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:800–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalasani N, Kahi C, Francois F, et al. Improved patient survival after acute variceal bleeding: A multicenter, cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:653–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB, Everhart JE. Improved survival after variceal hemorrhage over an 11-year period in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3566–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorbi D, Gostout CJ, Peura D, et al. An assessment of the management of acute bleeding varices: A multicenter prospective member-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2424–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.t01-1-07705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbonell N, Pauwels A, Serfaty L, Fourdan O, Levy VG, Poupon R. Improved survival after variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis over the past two decades. Hepatology. 2004;40:652–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.20339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grace ND, Bhattacharya K. Pharmacologic therapy of portal hypertension and variceal hemorrhage. Clin Liver Dis. 1997;1:59–75. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(05)70255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jalan R, Hayes PC. UK guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2000;46(Suppl 3–4):III1–15. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.suppl_3.iii1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Franchis R. Updating consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno III Consensus Workshop on definitions, methodology and therapeutic strategies in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2000;33:846–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grace ND. Diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to portal hypertension. American College of Gastroenterology Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1081–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lebrec D, Vinel JP, Dupas JL. Complications of portal hypertension in adults: A French consensus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:403–10. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200504000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qureshi W, Adler DG, Davila R, et al. Standards of Practice Committee ASGE Guideline: The role of endoscopy in the management of variceal hemorrhage, updated July 2005 Gastrointest Endosc 200562651–5.(Erratum in 2006;63:198). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Franchis R.Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension J Hepatol 200543167–76.(Erratum in 2005;43:547). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banares R, Albillos A, Rincon D, et al. Endoscopic treatment versus endoscopic plus pharmacologic treatment for acute variceal bleeding: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2002;35:609–15. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, et al. Emergency banding ligation versus sclerotherapy for the control of active bleeding from esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1997;25:1101–4. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laine L, Cook D. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:280–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-4-199508150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernard B, Grange JD, Khac EN, Amiot X, Opolon P, Poynard T. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1655–61. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Tsao G. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:405–6. doi: 10.1155/2004/769615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou MC, Lin HC, Liu TT, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis after endoscopic therapy prevents rebleeding in acute variceal hemorrhage: A randomized trial. Hepatology. 2004;39:746–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soares-Weiser K, Brezis M, Tur-Kaspa R, Paul M, Yahav J, Leibovici L. Antibiotic prophylaxis of bacterial infections in cirrhotic inpatients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:193–200. doi: 10.1080/00365520310000690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilbur K, Sidhu K. Antimicrobial therapy in patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:607–11. doi: 10.1155/2005/759360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, et al. Endoscopic variceal ligation plus nadolol and sucralfate compared with ligation alone for the prevention of variceal rebleeding: A prospective, randomized trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:461–5. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Pena J, Brullet E, Sanchez-Hernandez E, et al. Variceal ligation plus nadolol compared with ligation for prophylaxis of variceal rebleeding: A multicenter trial. Hepatology. 2005;41:572–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burroughs AK. The natural history of varices. J Hepatol. 1993;17(Suppl 2):S10–3. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: A meta-analytic review. Hepatology. 1995;22:332–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840220145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coffey RJ, Richards JS, Remmert CS, LeRoy SS, Schoville RR, Baldwin PJ. An introduction to critical paths. Qual Manag Health Care. 2005;14:46–55. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Podila PV, Ben-Menachem T, Batra SK, Oruganti N, Posa P, Fogel R. Managing patients with acute, nonvariceal gastrointestinal hemorrhage: Development and effectiveness of a clinical care pathway. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:208–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaman A, Hapke RJ, Flora K, Rosen HR, Benner KG. Changing compliance to the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of variceal hemorrhage: A regional survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:645–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilbur K, Sidhu K. Beta blocker prophylaxis for patients with variceal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:435–40. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000159222.16032.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]