Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is a rare condition that occurs when intraluminal gas and/or gas produced by intestinal bacteria enters the portal venous circulation. The most common precipitating factors include ischemia, intra-abdominal abscesses and inflammatory bowel disease. However, HPVG has recently been recognized as a rare complication of endoscopic and radiological procedures. Earlier studies advised immediate surgical intervention, but according to current recommendations, in some settings, HPVG can be managed conservatively. The present study reports two cases of HPVG; one that occurred following colonoscopy in a patient with severe Crohn’s disease and one in a patient with graft-versus-host disease.

METHODS:

The epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of HPVG are reviewed. Two case reports are presented, followed by the development of a management algorithm.

RESULTS:

Of the two patients that developed HPVG, one was an outpatient undergoing a colonoscopy for assessment of Crohn’s disease activity and the other was an inpatient with graft-versus-host disease. Once the diagnosis of HPVG was made, both patients were managed conservatively with antibiotic therapy and management of their underlying disease.

CONCLUSIONS:

HPVG can occur in the setting of severe gastrointestinal disease states and following endoscopic procedures. It is critical that gastroenterologists are aware of the differential diagnosis, pathogenesis, diagnostic approach and management of HPVG.

Keywords: Hepatic portal venous gas, Inflammatory bowel disease, Ischemia

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

La présence de gaz dans la veine porte hépatique (GVPH) est rare et survient lorsque des gaz intraluminaux et/ou produits par des bactéries intestinales pénètrent la circulation de la veine porte. Les facteurs déclencheurs les plus courants sont l’ischémie, les abcès intra-abdominaux et la maladie inflammatoire de l’intestin. Par contre, la présence de GVPH a récemment été reconnue comme une complication rare des interventions endoscopiques et radiologiques. Des études antérieures préconisaient une intervention chirurgicale immédiate, mais selon les recommandations actuelles, dans certains contextes, la présence de GVPH peut être traitée de manière conservatrice. La présente étude signale deux cas de GVPH, l’un survenu après une colonoscopie chez un patient atteint de maladie de Crohn avancée, et l’autre, chez un patient ayant présenté un rejet de greffe.

MÉTHODE :

L’épidémiologie, la pathogenèse, le diagnostic et le traitement du GVPH sont passés en revue ici. Deux rapports de cas sont présentés suivis d’un algorithme thérapeutique.

RÉSULTATS :

Des deux patients ayant développé un problème de GVPH, l’un était un patient non hospitalisé qui subissait une coloscopie pour évaluation de l’activité de sa maladie de Crohn et l’autre était un patient hospitalisé qui présentait un rejet de greffe. Une fois le diagnostic de GVPH posé, les deux patients ont été traités de manière conservatrice par antibiothérapie et traitement de la maladie sous-jacente.

CONCLUSION :

La présence de GVPH peut se manifester dans le contexte de graves maladies digestives et après des interventions endoscopiques. Il est important de sensibiliser les gastro-entérologues au diagnostic différentiel, à la pathogenèse, à l’approche diagnostique et au traitement des problèmes de GVPH.

Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is a rare condition that occurs when intraluminal gas or gas produced by gut bacteria enters the portal venous circulation. Although there have been numerous reported causes of HPVG, the majority are due to intestinal ischemia, with or without documented mesenteric thrombosis, and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (1–8). Other reported causes include infectious enteritis (3,9), Clostridium difficile-associated colitis (10,11), peptic ulcer disease (12), gastric cancer (13), metastatic gynecological cancers (13–15), inflammatory bowel disease (12,16–18), diverticulitis (19) and abdominal trauma (20,21). Early reports stated that HPVG was an ominous finding with an estimated mortality rate of 75% to 80% (22,23), but more recent studies suggest mortality rates of 25% to 35% (24,25). The improved survival may be due to the availability of more sensitive diagnostic imaging modalities (ie, ultrasonography [US] and computed tomography [CT] scanning) that can detect even minute quantities of air in the portal system. Although the number of iatrogenic HPVG cases has recently increased, these cases are usually associated with a better prognosis. For example, Chan et al (26) reported five patients with abdominal pain and HPVG on CT scanning due to ischemic gut, with a mortality rate of 100% within 48 h. This poor prognosis also holds true in the pediatric population, as one study (27) reported a 57.5% mortality rate in infants with HPVG-associated NEC.

Recently, several iatrogenic causes of HPVG have been recognized (Table 1). The management of these iatrogenic cases varied from surgical intervention, antibiotic therapy alone to simple observation (28,29). The majority of patients did well, with only one reported case of death after HPVG was induced by upper endoscopy in the intensive care unit setting (30).

TABLE 1.

Recognized causes of hepatic portal venous gas

| Category | Diseases processes or interventions |

|---|---|

| Bowel necrosis | Infectious colitis |

| Bowel ischemia | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | |

| Iatrogenic | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (37) |

| Gastric dilation (38) | |

| Gastric jejunal bypass (39) | |

| Air-contrast barium enema (28,29,40,41) | |

| Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy (42) | |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy (43–47) | |

| Sclerotherapy of gastric varices (48) | |

| Upper endoscopy (13,30) | |

| Colonoscopy (40,49,50) | |

| Abnormal motility | Ileus (51) |

| Intestinal pseudo-obstruction (40,51,52) | |

| Volvulus (53) | |

| Mechanical small bowel obstruction (33,54) | |

| Others | Intra-abdominal abscess |

| Gastric ulcer | |

| Intraperitoneal tumour |

Because HPVG can occur with numerous gastrointestinal and biliary diseases following gastrointestinal radiological procedures, endoscopy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, gastroenterologists should be familiar with this disease entity. In the current report, we present two cases: iatrogenic HPVG following colonoscopy in a patient with Crohn’s disease and spontaneous HPVG occurring in a patient following bone marrow transplantation (BMT), likely due to graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). We review the causes of HPVG, clinical presentation, diagnostic criteria, with emphasis on how to differentiate HPVG from air in the biliary tree, and management of this challenging and rare clinical condition.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

A 26-year-old woman with a three-year history of Crohn’s disease involving both the terminal ileum and colon underwent an outpatient colonoscopy to assess disease activity. Her clinical course had been characterized by frequent relapses despite immunomodulatory therapy (azathioprine 2.5 kg/day). The colonoscopy demonstrated extensive disease involving the terminal ileum, the cecum, and the ascending, transverse and descending colon. Multiple colonic biopsies were taken to rule out cytomegalovirus infection. Thirty minutes following the colonoscopy, she complained of right upper quadrant abdominal pain. She was mildly tender in the right upper quadrant, but there were no signs of peritonitis on physical examination. Chest and abdominal x-rays were reported as normal; however, on closer examination, tubular lucencies were noted in the liver (Figure 1). This was initially diagnosed as pneumobilia, but a second radiology review suggested that it was consistent with HPVG. An abdominal CT scan confirmed the diagnosis of HPVG and showed the classic sign of dilated vessels extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule (Figure 2). The patient was admitted to hospital and was not allowed any oral intake. Blood cultures were also obtained. The patient was immediately started on broad-spectrum antibiotics (tazobactam and metronidazole). General surgery was consulted and conservative management was recommended, because the patient was hemodynamically stable and there were no signs of perforation or bowel necrosis. Blood cultures were negative and an abdominal x-ray repeated 24 h later showed complete resolution of HPVG. Within 48 h, her abdominal pain had completely resolved and her abdominal examination was normal. The patient was discharged in good condition three days following her admission, and was started on a 14-day course of oral antibiotics (ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day and metronidazole 500 mg three times a day).

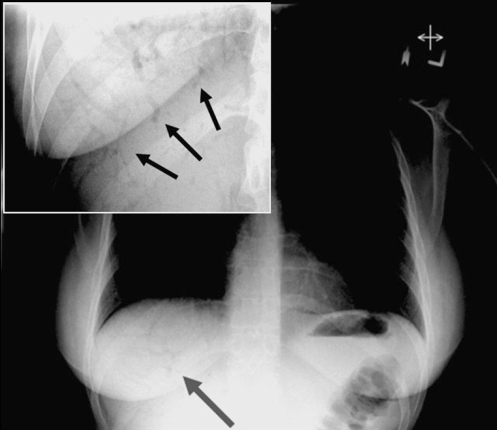

Figure 1).

Chest radiograph of patient 1 showing tubular branching lucencies projecting over the liver (arrow). Enlarged upright abdominal x-ray (inset) showing tubular branching lucencies (arrows)

Figure 2).

Computed tomography scan of patient 1 with hepatic portal venous gas, confirming the presence of gas in the portal veins. Note the branching pattern with a peripheral distribution extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule, involving predominantly the left liver lobe. Hepatic portal venous gas can be differentiated from pneumobilia, because in pneumobilia, the central air lucencies do not extend to within 2 cm of the liver capsule

Case 2

A 29-year-old man underwent allogenic BMT for chronic myeloid leukemia. His post-transplant course was complicated with febrile neutropenia and GVHD. On day 20 post-transplantation, he developed nausea, vomiting, watery diarrhea and fever of an unknown origin. On physical examination, he was found to have mild, diffuse abdominal tenderness but no peritoneal signs. Oral mucosal changes, as well as a skin rash on his trunk and arms, were consistent with GVHD. An abdominal CT scan noted classic findings for HPVG, and sigmoid biopsies (performed after the CT scan) diagnosed GVHD. After cultures were obtained, the patient was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole) and intravenous corticosteroids for GVHD. The patient rapidly responded and was asymptomatic for seven days. Two weeks following therapy, a follow-up CT scan showed complete resolution of HPVG, all blood cultures were negative and the patient was discharged home in stable condition.

DISCUSSION

In the present review, we describe two cases of HPVG, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition. The first patient had extensive abdominal imaging because of abdominal pain and fever after colonoscopy. In this case, the severe bowel ulcerations, air insufflation during colonoscopy and biopsy-induced mucosal injury may have played a role in producing HPVG. The second patient presented with fever of unknown origin after BMT. It is hypothesized that mucosal injury due to chemotherapy and GVHD were responsible for HPVG.

HPVG was first described by Wolfe and Evans (31) in 1955 in six infants who subsequently died from NEC. The first adult case was reported in 1960 by Susman and Senturia (32) in a patient with small bowel gangrene from superior mesenteric artery thrombosis. Most cases of HPVG are related to bowel necrosis and, in this setting, are often associated with a fatal outcome (26). In the past, HPVG was a very ominous radiological finding associated with a high mortality rate. Since the late 1980s, there have been increasing reports of patients surviving HPVG. This improved survival is likely due to the increased incidence of iatrogenic HPVG and enhanced detection by more sensitive diagnostic imaging modalities (eg, US and CT scan). In 2001, Kinoshita et al (12) reported 182 cases of HPVG. They reported an overall mortality rate of 39% in this case series, which is markedly lower than the mortality rate of 75% reported by Liebman et al (33) in 1978.

HPVG has been previously reported in Crohn’s disease patients occurring both spontaneously and following colonoscopy. In the review by Kinoshita et al (12), seven cases of HPVG were due to Crohn’s disease, and all these patients had a good clinical outcome. In most settings, HPVG is not in itself a predictor of mortality. Furthermore, there is no direct correlation between the amount of HPVG and mortality or morbidity. Generally, it is thought that previous poor prognosis of HPVG was mainly due to selection bias, whereby severely ill patients (commonly with bowel necrosis) were more likely to have undergone multiple radiographic studies.

Pathogenesis

The exact mechanism for HPVG is still unknown. The main factors that favour development of HPVG are intestinal wall alteration, bowel distention, ischemia and sepsis.

Intestinal wall alteration:

Many disease processes cause ulceration of the mucosal surface of the stomach, small intestine, colon and biliary tree, resulting in the passage of intraluminal air into the portomesentric venous system. Mucosal barrier disruption of any kind can theoretically result in HPVG, but it appears to be more common in intestinal ischemia, NEC, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and peptic ulcer disease. Theoretically, the deeper and more extensive the ulcerations, the greater the likelihood of these events occurring; however, this has not been well studied in the existing literature. Iatrogenic mucosal breaks, by endoscopic mucosal biopsy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related sphincterotomy, gastrostomy and sclerotherapy, can all result in HPVG.

Bowel distention:

This can produce mucosal disruption that allows intraluminal gas to become intravascular, but likely, in most settings of HPVG, there is some pre-existing mucosal break. Bowel distention has been a well-described iatrogenic cause of HPVG and appears to be most common following colonoscopies and barium enemas. It has also been described with paralytic ileus, mechanical obstruction and blunt trauma.

Sepsis:

Several infectious abdominal processes have been associated with HPVG, including diverticulitis, abdominal abscess, cholangitis, colitis and abdominal tuberculosis. The exact mechanisms in these settings could clearly vary and may include ischemia, mucosal ulceration and excessive gas production by invasive or luminal bacteria.

Diagnosis of HPVG

Although the diagnosis of HPVG can be made by normal abdominal x-rays (eg, CT scan or US), it appears that CT scanning is the gold standard. The diagnostic features of HPVG on CT imaging include: branching lucencies extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule, predominantly in the anterior-superior aspect of the left lobe (34). HPVG can be differentiated from biliary gas (pneumobilia) because the latter is associated with air within the central portion of the liver, which does not extend toward the liver capsule to the same extent as seen in HPVG (in HPVG, air extends to 2 cm or less from liver capsule; in pneumobilia, air extends to more than 2 cm from the liver capsule) (Figure 2). Air in the portal venous system is likely to be transported to the small peripheral branches in the liver by the centrifugal flow of portal venous blood, whereas gas in the biliary tree is prevented from migrating peripherally by the centripetal flow of the secreted bile (Figure 2) (35). The US features of HPVG have been reported as echogenic particles flowing within the portal vein (35).

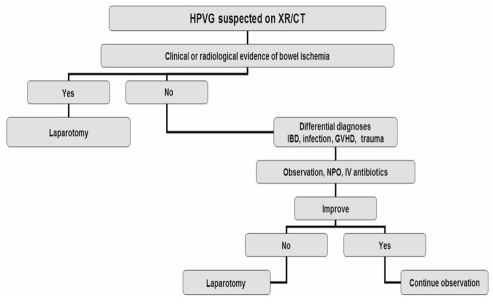

Management of HPVG

The treatment of this rare condition is controversial. Over the past 10 years, there has been a major shift from early surgical intervention with laparotomy to less aggressive therapy with observation and antimicrobial therapy (Figure 3). The key features that guide clinicians in their management approach is the presence or absence of peritonitis or bowel perforation, as well as the overall status of the patient (36). In clinically stable patients with no features of peritonitis or bowel perforation, intravenous fluid replacement, broad-spectrum antibiotics, close observation and no oral intake may prevent surgical intervention.

Figure 3.

Algorithm for the management of hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG). CT Computed tomography; GVHD Graft-versus-host disease; IBD Inflammatory bowel disease; IV Intravenous; NPO Nothing by mouth; XR X-ray

CONCLUSION

The presence of HPVG does not always indicate a catastrophic intra-abdominal event, but may be seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, complications of endoscopic procedures or other medical illnesses. In the setting of HPVG, medically stable patients without signs of bowel perforation or peritonitis can be potentially managed with supportive therapy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buras R, Guzzetta P, Avery G, Naulty C. Acidosis and hepatic portal venous gas: Indications for surgery in necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatrics. 1986;78:273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King S, Shuckett B. Sonographic diagnosis of portal venous gas in two pediatric liver transplant patients with benign pneumatosis intestinalis. Case reports and literature review. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:577–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02015354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurbegov AC, Sondheimer JM. Pneumatosis intestinalis in non-neonatal pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2001;108:402–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rehan VK, Seshia MM, Johnston B, Reed M, Wilmot D, Cook V. Observer variability in interpretation of abdominal radiographs of infants with suspected necrotizing enterocolitis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1999;38:637–43. doi: 10.1177/000992289903801102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.See C, Elliott D. Images in clinical medicine. Pneumatosis intestinalis and portal venous gas. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:e3. doi: 10.1056/ENEJMicm020289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alpern MB, Glazer GM, Francis IR.Ischemic or infarcted bowel: CT findings Radiology 1988166(1 Pt 1)149–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloom RA, Craciun E, Jurim O, Lebensart PD. Sonographic demonstration of hepatic venous gas in mesenteric arterial thrombosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;10:226–8. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198804000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradbury MS, Kavanagh PV, Bechtold RE, et al. Mesenteric venous thrombosis: Diagnosis and noninvasive imaging. Radiographics. 2002;22:527–41. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.3.g02ma10527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gruskay JA, Abbasi S, Anday E, Baumgart S, Gerdes J. Staphylococcus epidermidis-associated enterocolitis. J Pediatr. 1986;109:520–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jantsch H, Barton P, Fugger R, et al. Sonographic demonstration of septicaemia with gas-forming organisms after liver transplantation. Clin Radiol. 1991;43:397–9. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80568-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chezmar JL, Nelson RC, Bernardino ME. Portal venous gas after hepatic transplantation: Sonographic detection and clinical significance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:1203–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.153.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinoshita H, Shinozaki M, Tanimura H, et al. Clinical features and management of hepatic portal venous gas: Four case reports and cumulative review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1410–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.12.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiesner W, Mortele KJ, Glickman JN, Ji H, Ros PR. Portal-venous gas unrelated to mesenteric ischemia. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1432–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horowitz NS, Cohn DE, Herzog TJ, et al. The significance of pneumatosis intestinalis or bowel perforation in patients with gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;86:79–84. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dardik H, Mitsudo SM, Gilmore EC, Dardik I. Intrahepatic portal venous gas as a sequel to invasive ovarian adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1971;55:273–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujii K, Nakamura S, Hara J, et al. [Portal venous gas complicated with Crohn’s disease. A report of a case] Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2003;100:42–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delamarre J, Capron JP, Dupas JL, Deschepper B, Jouet-Gondry C, Rudelli A. Spontaneous portal venous gas in a patient with Crohn’s ileocolitis. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16:38–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01887301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirsch M, Bozdech J, Gardner DA. Hepatic portal venous gas: An unusual presentation of Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1521–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zielke A, Hasse C, Nies C, Rothmund M. Hepatic-portal venous gas in acute colonic diverticulitis. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:278–80. doi: 10.1007/s004649900652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalb D, Roberts S, Cumming J. Portal venous gas after blunt trauma: A case report. J Trauma. 2003;55:982–4. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000023168.75603.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingsley DD, Albrecht RM, Vogt DM. Gastric pneumatosis and hepatoportal venous gas in blunt trauma: Clinical significance in a case report. J Trauma. 2000;49:951–3. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200011000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cambria RP, Margolies MN. Hepatic portal venous gas in diverticulitis: Survival in a steroid-treated patient. Arch Surg. 1982;117:834–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380300074015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benson MD. Adult survival with intrahepatic portal venous gas secondary to acute gastric dilatation, with a review of portal venous gas. Clin Radiol. 1985;36:441–3. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(85)80339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faberman RS, Mayo-Smith WW. Outcome of 17 patients with portal venous gas detected by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1535–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.6.9393159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iannitti DA, Gregg SC, Mayo-Smith WW, Tomolonis RJ, Cioffi WG, Pricolo VE. Portal venous gas detected by computed tomography: Is surgery imperative? Dig Surg. 2003;20:306–15. doi: 10.1159/000071756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan SC, Wan YL, Cheung YC, Ng SH, Wong AM, Ng KK. Computed tomography findings in fatal cases of enormous hepatic portal venous gas. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2953–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i19.2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molik KA, West KW, Rescorla FJ, Scherer LR, Engum SA, Grosfeld JL. Portal venous air: The poor prognosis persists. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1143–5. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.25732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birnberg FA, Gore RM, Shragg B, Margulis AR. Hepatic portal venous gas: A benign finding in a patient with ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1983;5:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz BH, Schwartz SS, Vender RJ. Portal venous gas following a barium enema in a patient with Crohn’s colitis. A benign finding. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:49–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02555288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayakawa M, Gando S, Kameue T, Morimoto Y, Kemmotsu O. Abdominal compartment syndrome and intrahepatic portal venous gas: A possible complication of endoscopy. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1680–1. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolfe JN, Evans WA. Gas in the portal veins of the liver in infants; a roentgenographic demonstration with postmortem anatomical correlation. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1955;74:486–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Susman N, Senturia HR. Gas embolization of the portal venous system. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1960;83:847–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liebman PR, Patten MT, Manny J, Benfield JR, Hechtman HB. Hepatic – portal venous gas in adults: Etiology, pathophysiology and clinical significance. Ann Surg. 1978;187:281–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197803000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sebastia C, Quiroga S, Espin E, Boye R, Alvarez-Castells A, Armengol M. Portomesenteric vein gas: Pathologic mechanisms, CT findings, and prognosis. Radiographics. 2000;20:1213–24. 1224–6. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.5.g00se011213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Little AF, Ellis SJ. ‘Benign’ hepatic portal venous gas. Australas Radiol. 2003;47:309–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.2003.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou SK, Chern CH, How CK, Chen JD, Wang LM, Lee CH. Hepatic portal venous gas: Clinical significance of computed tomography findings. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:214–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai CF, Chang WT, Liang PC, Lien WC, Wang HP, Chen WJ. Pneumatosis intestinalis and hepatic portal venous gas after CPR. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:177–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Celoria G, Nardini A, Falco E, Montrucchio E, Pera M, Graziano M. [Intraportal air secondary to gastric dilatation. A clinical case] Minerva Chir. 1994;49:371–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mognol P, Chosidow D, Marmuse JP. Hepatic portal gas due to gastro-jejunal anastomotic leak after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2005;15:278–81. doi: 10.1381/0960892053268480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Celoria G, Coe NP. Does the presence of hepatic portal venous gas mandate an operation? A reassessment. South Med J. 1990;83:592–4. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199005000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moss ML, Mazzeo JT. Pneumoperitoneum and portal venous air after barium enema. Va Med Q. 1991;118:233–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pfaffenbach B, Wegener M, Bohmeke T. Hepatic portal venous gas after transgastric EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration of an accessory spleen. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:515–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herman JB, Levine MS, Long WB. Portal venous gas as a complication of ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:828–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barthet M, Membrini P, Bernard JP, Sahel J.Hepatic portal venous gas after endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy Gastrointest Endosc 199440(2 Pt 1)261–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blind PJ, Oberg L, Hedberg B. Hepatic portal vein gas following endoscopic retrograde cholangiography with sphincterotomy. Case report. Eur J Surg. 1991;157:299–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merine D, Fishman EK. Uncomplicated portal venous gas associated with duodenal perforation following ERCP: CT features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13:138–9. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198901000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simmons TC. Hepatic portal venous gas due to endoscopic sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:326–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen HN, Purucker E, Riehl J, Matern S. Hepatic portal venous gas following emergency endoscopic sclerotherapy of gastric varices. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1767–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huycke A, Moeller DD. Hepatic portal venous gas after colonoscopy in granulomatous colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:637–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Czechowski JJ, Slezak P. Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) Rofo. 1984;140:349–51. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1052989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quirke TE. Hepatic-portal venous gas associated with ileus. Am Surg. 1995;61:1084–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Sandick JW, van Lanschot JJ. Portal venous air and pneumatosis intestinalis. Dig Surg. 2001;18:279. doi: 10.1159/000050151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan EC, Jager GJ, Bleeker WA, Van Goor H. Portal venous air in an adult patient with obstructive small bowel volvulus. Dig Surg. 2002;19:400–2. doi: 10.1159/000065819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rha SE, Ha HK, Lee SH, et al. CT and MR imaging findings of bowel ischemia from various primary causes. Radiographics. 2000;20:29–42. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.1.g00ja0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]