Abstract

The marked change in a woman's hormonal profile that happens at menopause affects many aspects of behaviour. We investigated circum-menopausal women's preferences for femininity in the faces of young adult men and women. Post-menopausal women demonstrated stronger preferences for femininity in same-sex faces than pre-menopausal women did. This effect was independent of possible effects of participant's age and suggests that dislike of feminine (i.e. attractive) same-sex competitors decreases as fertility decreases. No significant difference between pre- and post-menopausal women was observed for men's faces, potentially because circum-menopausal women do not necessarily view young adult men as potential mates. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate circum-menopausal changes in women's face preferences.

Keywords: sexual dimorphism, facial attractiveness, menopause, menstrual cycle, derogation

1. Introduction

Women's preferences for masculinity in men's faces are enhanced during the late follicular (i.e. fertile) phase of the menstrual cycle (e.g. Penton-Voak et al. 1999; Jones et al. 2005; Welling et al. 2007). Since facial masculinity is positively related to men's long-term health (Thornhill & Gangestad 2006), enhanced preferences for masculinity in men's faces during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle may increase offspring health (Gangestad & Thornhill 2008; Jones et al. 2008).

While many studies have investigated the effects of menstrual cycle phase on women's judgements of the attractiveness of men's faces, fewer have investigated whether menstrual cycle phase also affects women's judgements in the attractiveness of women's faces. Fisher (2004) found that women gave lower attractiveness ratings to women's faces when the raters were in phases of the menstrual cycle in which oestrogen levels are raised than in other phases. No such difference was found for men's faces. Fisher (2004) suggested that decreased attractiveness ratings of women's faces when oestrogen levels are high reflect increased derogation of same-sex competitors at these times. Consistent with this proposal, Welling et al. (2007) and Jones et al. (2005) found that women's preferences for feminine (i.e. attractive, Perrett et al. 1998) women are decreased around ovulation.

Although, many studies have investigated the effects of menstrual-cycle phase on face preferences, we know of no studies that have tested for circum-menopausal changes in face preferences. This is somewhat surprising, since menopause is associated with decreased fertility (Gilbert 2000) and a shift away from a mating-orientated psychology towards a more family- and community-oriented psychology (Hawkes et al. 1998). Consequently, we investigated circum-menopausal women's preferences for feminized faces. Because women's preferences for masculinity in men's faces are enhanced during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle, post-menopausal women may show stronger preferences for feminine men than pre-menopausal women do. If women are also more likely to derogate attractive same-sex competitors when fertility is high, post-menopausal women may show stronger preferences for feminine (i.e. attractive) female faces than pre-menopausal women do.

2. Material and methods

(a) Stimuli

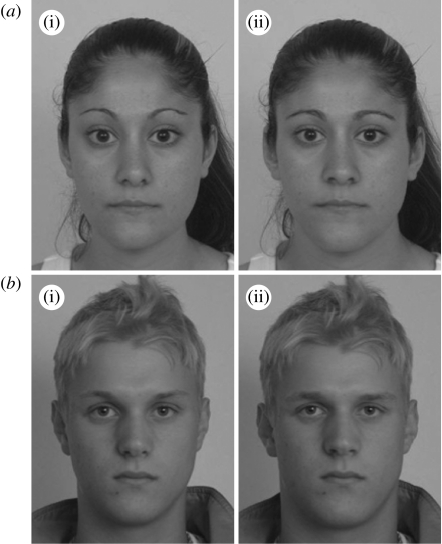

Following previous studies of attractiveness (Penton-Voak et al. 1999; Jones et al. 2005; DeBruine et al. 2006; Welling et al. 2007), we used prototype-based image transformations to objectively manipulate sexual dimorphism of two-dimensional shape in face images. Male and female prototypes were manufactured by averaging the shapes of a group of 60 male or 60 female faces. These prototypes were used to transform the face images of 20 white men (mean=19.5 years, s.d.=2.3) and 20 white women (mean=18.4 years, s.d.=0.7) by adding or subtracting 50 per cent of the linear differences in two-dimensional shape between the male and female prototypes. This process creates masculinized and feminized versions (figure 1) of the images that differ in sexual dimorphism of two-dimensional shape and that are matched in other regards (e.g. skin colour, Tiddeman et al. 2001). These male and female faces have been used in a previous study of menstrual cycle effects on face preferences (Welling et al. 2007). Welling et al. (2007) demonstrated that women perceive the feminized versions as being more feminine than the masculinized versions, confirming that our image manipulation affects perceptions of femininity in the predicted manner.

Figure 1.

Examples of (a(i),b(i)) feminized and (a(ii),b(ii)) masculinized male and female faces used in our study.

(b) Procedure

Ninety-seven white women participated in the study (mean=48.75 years, s.d.=6.52; range=40–64 years). Forty-five of the women (the post-menopausal group) reported that, as a consequence of menopause, they no longer experienced menses. Fifty-two of the women (the pre-menopausal group) reported that they continued to experience menses. Women in our study were selected for reporting no use of hormone replacements or hormonal contraceptives.

Participants were shown the 40 pairs of face images and were asked to choose the face in each pair that they considered more attractive. Each pair consisted of a masculinized and a feminized version of the same individual. The order in which the pairs of faces were shown, and the side of the screen on which any particular image was shown were fully randomized. This method has been used in many previous studies of face preferences (e.g. Jones et al. 2005; DeBruine et al. 2006; Welling et al. 2007).

The study was conducted online. Previous studies have demonstrated that online and laboratory studies of variation in face preferences produce equivalent patterns of results (e.g. Jones et al. 2005, 2007).

3. Results

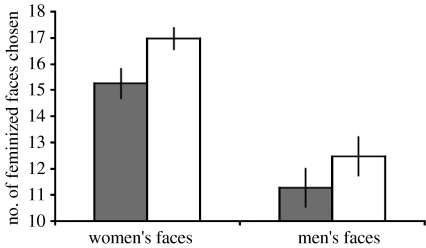

For each participant, we calculated the number of times they chose feminized female faces (out of 20) and feminized male faces (out of 20). ANCOVA (within-subjects factor: sex of face (male, female); between-subjects factor: circum-menopausal status (pre-menopause, post-menopause); covariate: participant age) revealed a significant main effect of sex of face (F1,94=13.05, p<0.001), whereby women were more likely to choose feminine faces when judging women's faces (mean=16.05, s.e.m.=0.37) than when judging men's faces (mean=11.82, s.e.m.=0.52). There were also significant interactions between sex of face and circum-menopausal status (F1,94=4.68, p=0.033, figure 2) and between sex of face and participant age (F1,94=8.18, p=0.005). The main effects of circum-menopausal status (F1,94=0.67, p=0.414) and participant age (F1,94=2.01, p=0.159) were not significant.

Figure 2.

The significant interaction between sex of face and circum-menopausal status. On the y-axis, 10=chance (i.e. no preference for feminized or masculinized faces). Bars show actual (i.e. observed) means and s.e.m. Grey bars, pre-menopausal; white bars, post-menopausal.

Next, we carried out separate ANCOVAs for male and female faces. For female faces, there was a significant main effect of circum-menopausal status (F1,94=6.07, p=0.016) and no main effect of participant age (F1,94=0.89, p=0.346). For male faces, there was a significant main effect of participants' age (F1,94=6.53, p=0.012) and no main effect of circum-menopausal status (F1,94=0.46, p=0.498). Participants’ age and the number of feminized males chosen were positively correlated (r=0.27, n=97, p=0.007).

Separate regression analyses for male and female face preferences with circum-menopausal status and age as predictors were also carried out. The analysis for female faces (F2,94=3.33, p=0.040) showed a significant effect of circum-menopausal status (t=2.46, p=0.016, β=0.316) but no significant effect of age (t=−0.95, p=0.346, β=−0.122). The analysis for male faces (F2,94=3.98, p=0.022) showed a significant effect of age (t=2.55, p=0.012, β=0.326) but no significant effect of circum-menopausal status (t=−0.68, p=0.498, β=−0.087). Repeating the ANCOVA and regression analyses above with arcsine-transformed face preference scores (to remove dependence of the variance on the means) revealed the same pattern of significant results as our prior analyses. Frequency scores were converted to proportions out of the maximum possible number of times feminized faces could be chosen for each sex (i.e. 20) before the arcsine transform was applied.

One-sample t-tests comparing the number of times feminized faces were chosen with the chance value of 10 showed that women chose the feminized versions of women's (t(96)=16.47, p<0.001) and men's (t(96)=3.54, p<0.001) faces significantly more often than chance.

We repeated our initial ANCOVA with partnership status (partnered, unpartnered) included as a factor. Forty-six women reported that they were in a relationship and 28 women reported being single (23 women did not provide these data and were excluded from this analysis). Including partnership status in the ANCOVA did not affect the interactions between sex of face and circum-menopausal status (F1,69=7.47, p=0.008) and between sex of face and participant age (F1,69=7.62, p=0.007).

4. Discussion

As we predicted, post-menopausal women's preferences for femininity in women's faces were significantly stronger than those of pre-menopausal women. This effect was independent of possible effects of participant age. Although, this same pattern was evident for judgements of men's faces, the difference was not significant and was significantly smaller than the difference for women's faces. Thus, our findings show that differences among circum-menopausal women in the strength of their preferences for feminine faces were driven by differences between pre- and post-menopausal women in the strength of their preferences for feminine women.

Consistent with previous findings (e.g. Perrett et al. 1998), women in our study demonstrated strong preferences for femininity in women's faces. Thus, stronger preferences for feminine (i.e. attractive) women among post-menopausal women than among pre-menopausal women supports the proposal that derogation of attractive same-sex competitors is more pronounced when fertility is high (Fisher 2004; Jones et al. 2005; Welling et al. 2007). It is important to note here, however, that both the women in the pre- and post-menopausal groups demonstrated strong preferences for feminine women (figure 2). Thus, the effect of menopause on women's preferences for femininity reflects stronger attraction to feminine women in the post-menopausal group than in the pre-menopausal group, rather than the pre-menopausal group preferring masculine women while the post-menopausal group prefer feminine women.

While our prediction of changed preferences for feminine women among circum-menopausal women was supported, we found limited evidence that post-menopausal women demonstrate stronger preferences for feminine men than pre-menopausal women do. Although post-menopausal women tended to show stronger preferences for feminine men than pre-menopausal women did (figure 2), this effect of menopause was not significant for men's faces. One possibility is that circum-menopausal women do not view the age group from which our face stimuli were manufactured (i.e. young adult men in their late teens) as potential mates. Effects of hormonal profile on attractiveness judgements of opposite-sex individuals may be more pronounced when judging peers (i.e. probable mates) than when judging much younger individuals (i.e. unlikely mates). We speculate that this may explain why we found no significant effect of menopause on women's judgements of men's faces and is consistent with the unexpected positive association that we observed between preferences for feminine men and participant age.

An effect of menopause on women's preferences for feminine women would be expected for judgements of this age group of faces, however, if attractive young adult women pose a threat to circum-menopausal women's romantic relationships or their chances of attracting a partner. Such a threat seems probable since circum-menopausal women's romantic relationships are typically with men who are close to their own age and men in this age group are known to demonstrate strong preferences for young adult women (Buss 1994). Future studies investigating the effects of menopause on women's preferences for femininity in face stimuli of different ages may shed light on this point. Such studies could also assess the extent to which circum-menopausal changes in femininity preferences reflect changes in preferences for sexually dimorphic or neotenous facial characteristics. That we found no comparable effect of menopause for judgements of men's faces suggests that stronger preferences for feminine women among post-menopausal women than among pre-menopausal women is not simply a consequence of post-menopausal women being more attentive when judging the attractiveness of faces generally.

We show here that circum-menopausal women's preferences for femininity in young adult women's faces are stronger following menopause, suggesting that the effects of within-sex competition on judgements of the attractiveness of other women decreases as fertility decreases (Gilbert 2000) and as circum-menopausal women shift away from a mating-oriented psychology (Hawkes et al. 1998). The hormonal changes that might underpin circum-menopausal changes in judgements of women's facial attractiveness are unknown. However, studies showing that derogation of the attractiveness of other women is strongest on days of the menstrual cycle when oestrogen levels are high (Fisher 2004), together with findings of lowered oestrogen following menopause (Gilbert 2000), suggest that circum-menopausal changes in face preferences may reflect changes in oestrogen levels. Investigating the effects of circum-menopausal changes in oestrogen levels, together with changes in other hormones and ratios of hormones, may provide insight into the mechanisms that underpin circum-menopausal changes in women's face preferences.

References

- Buss D.M. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1994. The evolution of desire. [Google Scholar]

- DeBruine L.M., et al. Correlated preferences for facial masculinity and ideal or actual partner's masculinity. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2006;273:1355–1360. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3445. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M.L. Female intrasexual competition decreases female facial attractiveness. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2004;271:S283–S285. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0160. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangestad S.W., Thornhill R. Human oestrus. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2008;275:991–1000. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1425. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert S.F. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 2000. Developmental biology. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes K., O'Connell J.F., Blurton Jones N.G., Alvarez H., Charnov E.L. Grandmothering, menopause, and the evolution of human life histories. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1336–1339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1336. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.3.1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.C., DeBruine L.M., Little A.C., Conway C.A., Welling L.L.M., Smith F.G. Sensation seeking and men's face preferences. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2007;28:439–446. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.07.006 [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.C., DeBruine L.M., Perrett D.I., Little A.C., Feinberg D.R., Law Smith M.J. Effects of menstrual cycle phase on face preferences. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2008;37:78–84. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9268-y. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9268-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.C., Little A.C., Boothroyd L., DeBruine L.M., Feinberg D.R., Law Smith M.J., Cornwell R.E., Moore F.R., Perrett D.I. Commitment to relationships and preferences for femininity and apparent health in faces are strongest on days of the menstrual cycle when progesterone level is high. Horm. Behav. 2005;48:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.03.010. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penton-Voak I.S., Perrett D.I., Castles D.L., Kobayashi T., Burt D.M., Murray L.K., Minamisawa R. Menstrual cycle alters face preference. Nature. 1999;399:741–742. doi: 10.1038/21557. doi:10.1038/21557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrett D.I., Lee K.J., Penton-Voak I.S., Rowland D.R., Yoshikawa S., Burt D.M., Henzi S.P., Castles D.L., Akamatsu S. Effects of sexual dimorphism on facial attractiveness. Nature. 1998;394:884–887. doi: 10.1038/29772. doi:10.1038/29772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill R., Gangestad S.W. Facial sexual dimorphism, developmental stability, and susceptibility to disease in men and women. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2006;27:131–144. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.06.001 [Google Scholar]

- Tiddeman B., Burt M., Perrett D. Prototyping and transforming facial textures for perception research. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2001;1:42–50. doi:10.1109/38.946630 [Google Scholar]

- Welling L.L.M., Jones B.C., DeBruine L.M., Conway C.A., Law Smith M.J., Little A.C., Feinberg D.R., Sharp M., Al-Dujaili E.A.S. Raised salivary testosterone in women is associated with increased attraction to masculine faces. Horm. Behav. 2007;52:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.01.010. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]