Abstract

Purpose: To assess the incremental value of the left-side-down decubitus view in radiographic evaluation of ileocolic intussusception.

Materials and Methods: The institutional review board approved this retrospective investigation with waiver of informed consent. Between February 24, 2002, and January 25, 2007, 304 studies (300 patients; mean age, 1.3 years; range, 0.1–3.9 years) met the following inclusion criteria: kidney ureter bladder (KUB) and decubitus views obtained, with subsequent proof of diagnosis. Using a consensus approach, two pediatric radiologists evaluated KUB and decubitus views for four variables: (a) discrete mass and (b) small-bowel obstruction (positive criteria); (c) air or stool in ascending colon and (d) cecal air or stool (negative criteria). On the basis of these criteria, each study was graded as negative, positive, or indeterminate for intussusception. Diagnostically determinate studies and the ability to visualize or exclude intussusception were calculated to determine sensitivity and specificity. The difference between proportions was calculated, along with 95% confidence intervals. Agreement between the supine KUB view and supine KUB plus left-side-down decubitus views was tested with the McNemar test.

Results: Intussusception was present in 58 of 304 studies (19%). Adding the decubitus view to the KUB view increased the number of determinate studies from 110 of 304 (36.2%) to 205 of 304 (67.4%) (difference, 31.2 percentage points; P < .001). Intussusception was correctly identified with KUB view alone in 35 of 58 studies (60.3%); this value increased to 43 of 58 (74.1%) with KUB plus decubitus views (P = .0215). Intussusception was correctly excluded with the KUB view alone in 63 of 246 studies (25.6%); this increased to 143 of 246 studies (58.1%) with addition of the decubitus view (P < .0001).

Conclusion: The addition of decubitus views increased the number of diagnostically determinate studies and increased the ability to diagnose or exclude intussusception. The authors believe that a left-side-down decubitus view should be included in the initial evaluation of patients suspected of having intussusception, particularly when the supine view is diagnostically indeterminate.

© RSNA, 2008

Infants suspected of having ileocolic intussusception are typically referred to the radiology department, where their work-up usually begins with radiography, followed by ultrasonography (US) or enema as needed (1,2). When radiographs do not clearly depict the ascending colon and cecum as outlined by stool or gas, they are often unhelpful in establishing a probability of the presence or absence of intussusception and are therefore unhelpful in guiding subsequent care.

Published data on the utility of radiographic diagnosis and exclusion of intussusception vary (2), with more recent literature indicating that radiographic diagnosis of intussusception is made in only 29% of cases (3). Many abdominal series include a kidney, ureter, bladder (KUB) view with an upright radiograph to assess for bowel obstruction and free intraperitoneal air (2,4–6). However, a key to evaluation of a radiograph for ileocolic intussusception is identifying the cecum and ascending colon; these structures are largely seen as water density on an upright view, which directs gas toward the upper abdomen. One method used to visualize the cecum and ascending colon is to obtain a prone radiograph, which tends to direct gas from the transverse colon to the more posteriorly located ascending colon and cecum, but this approach is not helpful in evaluating for free air. Left-side-down decubitus positioning with a horizontal beam also directs air into the nondependent ascending colon and cecum. In theory, this view would improve accuracy in radiographic assessment of suspected ileocolic intussusception while allowing evaluation for differential air-fluid levels and free intraperitoneal air.

For many years at our institution, we have obtained a KUB radiograph and a decubitus radiograph in patients suspected of having intussusception. The purpose of this investigation was to review these examinations to assess the incremental value of the left-side-down decubitus view over the KUB view in radiographic evaluation of ileocolic intussusception.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection

This retrospective investigation was approved by our institutional review board, with waiver of informed consent. We identified 342 studies performed between February 24, 2002, and January 25, 2007, that met the following inclusion criteria: patient younger than 4 years and radiographic evaluation with KUB and left-side-down decubitus views obtained for the suspicion of intussusception, with subsequent US, therapeutic air enema, or clinical follow-up considered to be proof of diagnosis. Clinical proof was determined according to the clinical visit after the initial presentation for the evaluation of suspected intussusception.

Thirty-eight studies were excluded because of (a) preexisting contrast material from a previous barium study or computed tomography performed at another institution, (b) improper radiographic technique (eg, rotated decubitus or supine view), or (c) a similar examination performed within 10 days at our institution for the same clinical indication. The remaining 304 studies performed in 300 patients (mean age, 1.3 years; range, 0.1–3.9 years; 204 male patients [mean age, 1.3 years; range, 0.2–3.9 years] and 96 female patients [mean age, 1.5 years; range, 0.1–3.9 years]) constituted our study population (Fig 1). Four patients underwent two studies each, with an average time between studies of 78 days (range, 48–162 days).

Figure 1:

Flowchart of patient inclusion.

Image Analysis

The KUB radiograph and the KUB plus decubitus radiograph set were each evaluated through consensus review by two Certificate of Added Qualification–certified pediatric radiologists (J.H.K., 2 years of experience; M.H., 22 years of experience) who were blinded to the final diagnosis. The KUB radiograph alone was first reviewed and scored. The KUB with decubitus view radiograph set was subsequently reviewed and scored. Each radiograph was evaluated for four positive or negative variables: (a) discrete intracolonic mass and (b) small-bowel obstruction (the two positive criteria); (c) presence of air or stool in the ascending colon and (d) presence of air or stool in the cecum (the two negative criteria).

The two negative criteria were qualitatively scored on a scale of 1–5 (1 = well delineated; 5 = not seen at all). A score of 1 was assigned when the ascending colon or cecum was definitively identified and clearly delineated with stool or air which could be followed to the level of the hepatic flexure. A score of 2 was assigned when the colon or cecum was identified at the right paracolic gutter but could not be clearly followed in continuity to the hepatic flexure. A score of 3 was assigned when the identification of ascending colon and cecum was equivocal. A score of 4 was assigned when there was questionable absence of gas and stool within the ascending colon or cecum. A score of 5 was assigned when there was unquestionable absence of recognizable ascending colon or cecal contents.

Studies were divided into those with diagnostically determinate results and those with diagnostically indeterminate results. For studies with results considered diagnostically determinate, the diagnosis or exclusion of intussusception was made for both the KUB radiograph alone and the KUB plus decubitus set, based on assessment of the four scored variables and subsequent overall general impression. The final impression for determinate studies was based on the scale assigned to both the KUB radiograph and the KUB plus decubitus set, such that radiographs with high positive or negative scores were appropriately graded positive or negative for intussusception, respectively.

Data Review

The total number of intussusceptions correctly identified with the KUB view alone and with the KUB plus decubitus views was calculated. In addition, the following parameters were calculated for the KUB view alone and for the KUB plus decubitus views: the number of studies that were considered to have diagnostically determinate results (ie, clearly visible ascending colon and cecum) and the percentage showing small-bowel obstruction or a discrete mass. Finally, the sensitivity and specificity were calculated for the KUB and for the KUB plus decubitus views. Sensitivity and specificity values were calculated for the studies with results considered diagnostically determinate and for the entire study population (for sensitivity, studies with diagnostically indeterminate results were considered false negative; for specificity, studies with diagnostically indeterminate results were considered false positive).

Statistical Analysis

The proportions of patients with the study end points are summarized, along with their 95% confidence intervals. These confidence intervals are asymptotic or exact, as appropriate, depending on the number of the end-point events. The difference between proportions was calculated, along with its 95% confidence interval, as the primary means of comparison. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated to study the properties of the supine KUB radiograph and the supine KUB plus left-side-down decubitus radiograph set, with the reference standard being clinical, US, or enema follow-up. The agreement between supine KUB and supine KUB plus left-side-down decubitus radiographs on different study end points was tested by using the McNemar test. P values less than .05 were considered to represent significant findings. All tests were two tailed. Statistical analyses were performed with commercial software (SAS for Windows, version 9; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There was no significant difference in mean age between female (1.5 years) and male (1.3 years) patients (P = .11) who presented for the work-up of intussusception. There was no significant difference between determinate and indeterminate groups based on age or sex. Intussusception was present in 58 of 304 patients (19%). Intussusception was present in 22% of patients aged 1 year and younger, 18% of children aged 1–1.9 years, and 15% of those aged 2.0–3.9 years. There was no significant difference in incidence of intussusception among these three age groups (P = .38).

The combination of KUB plus decubitus radiographs, compared with the KUB radiograph alone, decreased indeterminate results from 194 of 304 studies (63.8%) to 99 of 304 studies (32.6%) (difference, −31.2 percentage points; P < .001). Conversely, studies with determinate results increased from 110 of 304 (36.2%) to 205 of 304 (67.4%) (difference, 31.2 percentage points; P < .001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sensitivity and Specificity for Supine versus Supine plus Decubitus Views in the Evaluation for Intussusception

Note.—Data in parentheses are percentages.

Difference (expressed as percentage points) = 31.2.

Sensitivity and specificity calculations for all studies: An indeterminate study result was considered false positive or false negative for specificity and sensitivity calculations, respectively.

Intussusception was correctly identified with KUB radiographs alone in 35 of 58 studies (60.3%); this increased to 43 of 58 studies (74.1%) with the combination of KUB and decubitus radiographs (P = .0215). Intussusception was correctly excluded with KUB radiographs alone in 63 of 246 studies (25.6%); this increased to 143 of 246 studies (58.1%) with the combination of KUB and decubitus radiographs (P < .0001). For all studies, sensitivity and specificity were 60.3% and 25.6%, respectively, for KUB radiographs alone and were 74.1% and 58.1%, respectively, for KUB plus decubitus radiographs; both values were significant (Table 1). Among studies with determinate results alone, sensitivity and specificity for KUB radiographs alone were 92.1% and 87.5%, respectively. For KUB plus decubitus radiographs, sensitivity decreased to 89.6% (because studies with indeterminate results were eliminated), but specificity increased to 91.1%; neither was significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity and Specificity, Excluding Patients with Indeterminate Study Results

Note.—Data in parentheses are percentages, and data in brackets are 95% confidence intervals.

Identification of the ascending colon and cecum occurred significantly more often with the KUB plus decubitus radiograph set (P < .0001). As expected, when the ascending colon and the cecum were both unequivocally identified (Figs 2, 3), the rate of appropriate exclusion of intussusception was very high (Table 3).

Figure 2a:

Radiographs of 19-month-old child with no intussusception. (a) On the supine view, the cecum and ascending colon cannot be delineated; therefore, intussusception cannot be excluded. (b) With left-side-down decubitus positioning, air moves to the ascending colon and cecum (arrow), and ileocolic intussusception can be confidently excluded.

Figure 2b:

Radiographs of 19-month-old child with no intussusception. (a) On the supine view, the cecum and ascending colon cannot be delineated; therefore, intussusception cannot be excluded. (b) With left-side-down decubitus positioning, air moves to the ascending colon and cecum (arrow), and ileocolic intussusception can be confidently excluded.

Figure 3a:

Radiographs of 2-year-old child with no intussusception. (a) Supine view demonstrates multiple gas-distended loops of bowel. The cecum and colon cannot be delineated with confidence. It is difficult to distinguish distended ascending colon and a potentially redundant sigmoid, or even small bowel in the right lower quadrant. Therefore, intussusception cannot be excluded. (b) With left-side-down decubitus positioning, air now delineates the ascending colon and cecum and helps differentiate these loops from sigmoid colon; ileocolic intussusception can be confidently excluded.

Figure 3b:

Radiographs of 2-year-old child with no intussusception. (a) Supine view demonstrates multiple gas-distended loops of bowel. The cecum and colon cannot be delineated with confidence. It is difficult to distinguish distended ascending colon and a potentially redundant sigmoid, or even small bowel in the right lower quadrant. Therefore, intussusception cannot be excluded. (b) With left-side-down decubitus positioning, air now delineates the ascending colon and cecum and helps differentiate these loops from sigmoid colon; ileocolic intussusception can be confidently excluded.

Table 3.

Frequency of Identification of Ascending Colon and Cecum

Note.—Data in parentheses are percentages.

Nine of 58 intussusceptions (16%) were seen only with the addition of decubitus views (five transverse colon, two ascending colon [Fig 4], and two hepatic flexure). However, there was one splenic flexure intussusception correctly identified with the supine view that was equivocal with the decubitus view. No patient had free intraperitoneal air. With decubitus views, there was a slight but not significant improvement in the detection of small-bowel obstruction and in the identification of an intracolonic mass in patients with intussusception (Table 4).

Figure 4a:

Radiographs of 2-year-old child with intussusception. (a) Supine view depicts a nonobstructive bowel gas pattern. The cecum and ascending colon cannot be delineated, but the radiograph is indeterminate for intussusception. (b) With left-side-down decubitus positioning, air moves to the ascending colon and delineates the intussusceptum (arrows).

Figure 4b:

Radiographs of 2-year-old child with intussusception. (a) Supine view depicts a nonobstructive bowel gas pattern. The cecum and ascending colon cannot be delineated, but the radiograph is indeterminate for intussusception. (b) With left-side-down decubitus positioning, air moves to the ascending colon and delineates the intussusceptum (arrows).

Table 4.

Frequency of Identification of Small-Bowel Obstruction or Intracolonic Mass in Patients with Intussusception

Note.—Data in parentheses are percentages.

There were several pitfalls in the interpretation of both the KUB radiograph and the left lateral decubitus radiograph. A gas-filled sigmoid colon or small bowel may move into the right half of the abdomen and be mistaken for the cecum or ascending colon. Decubitus views were helpful in some of these cases (ie, when the gas in the paracolic gutter could not be definitely followed to the transverse colon) (Fig 5).

Figure 5a:

Radiographs of 11-month-old infant with intussusception. (a) Supine view demonstrates a paucity of gas in the right half of abdomen and the suggestion of stool in the proximal transverse colon. (b) With left-side-down decubitus positioning, the sigmoid colon can be delineated in the right half of abdomen, extending to the hepatic edge. However, the transverse colon is now well delineated with gas, and the gas column is interrupted without reaching the ascending colon. A cecal ileocolic intussusception was demonstrated with US and enema.

Figure 5b:

Radiographs of 11-month-old infant with intussusception. (a) Supine view demonstrates a paucity of gas in the right half of abdomen and the suggestion of stool in the proximal transverse colon. (b) With left-side-down decubitus positioning, the sigmoid colon can be delineated in the right half of abdomen, extending to the hepatic edge. However, the transverse colon is now well delineated with gas, and the gas column is interrupted without reaching the ascending colon. A cecal ileocolic intussusception was demonstrated with US and enema.

A second pitfall for a false-negative study was the presence of a proximal intussusception in the cecum, with air or stool delineation of the ascending colon without delineation of the cecum deeper in the right lower quadrant, even on the decubitus radiograph (Fig 6). Decubitus positioning, however, helps delineate intussusceptions of the ascending colon that are not initially demonstrated with supine KUB radiography alone (Figs 4, 6).

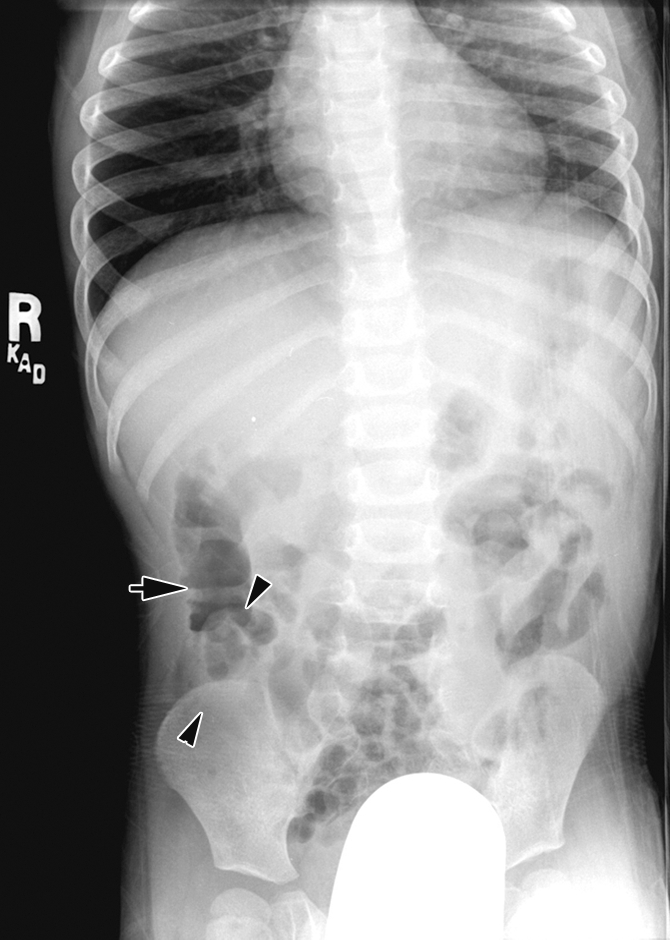

Figure 6a:

Radiographs of 3-year-old child with intussusception confined to the cecum. (a) Supine view shows a nonobstructive bowel gas pattern. Neither the ascending colon nor the cecum is identifiable with certainty. (b) Decubitus view delineates the ascending colon more clearly (arrow), but the cecum was not seen, and study was given a score of 5. Therefore, this study was considered diagnostically indeterminate for intussusception. This patient had a cecal intussusception confirmed by using US and enema that in retrospect can be seen on the decubitus view (arrowheads in a and b).

Figure 6b:

Radiographs of 3-year-old child with intussusception confined to the cecum. (a) Supine view shows a nonobstructive bowel gas pattern. Neither the ascending colon nor the cecum is identifiable with certainty. (b) Decubitus view delineates the ascending colon more clearly (arrow), but the cecum was not seen, and study was given a score of 5. Therefore, this study was considered diagnostically indeterminate for intussusception. This patient had a cecal intussusception confirmed by using US and enema that in retrospect can be seen on the decubitus view (arrowheads in a and b).

A third pitfall is outlined by the one case in which the intussusception was located at the splenic flexure. Since left-side-down decubitus positioning moves gas toward the right half of the abdomen, this intussusception was less clearly seen on the decubitus radiograph but was depicted with the KUB plus decubitus radiograph combination. Most intussusceptions are located near the hepatic flexure or in the mid transverse colon, and are better seen with the decubitus view (as shown in 16% of our patients, in whom only the decubitus view was diagnostic).

DISCUSSION

The imaging work-up of ileocolic intussusception in infants often begins with radiographs. The utility of radiography in this diagnosis has been challenged in the past, and in recent years, US has become the definitive diagnostic modality of choice (2,7). However, an abdominal series remains an important initial examination to determine whether there is free intraperitoneal air or small-bowel obstruction, which affects acuity in diagnosis and patient management. Our results indicate that the combination of a KUB view plus a left lateral decubitus view helps increase the number of diagnostically determinate radiographic studies. The use of the left-side-down decubitus view as the second view provides additional important preliminary information and can help direct the most expedient subsequent patient care.

In many cases, the abdominal series consists of a KUB view and an upright view, which directs air toward the upper portion of the abdomen and fluid toward the lower portion of the abdomen and the right lower quadrant. Although this view is helpful in depicting free air and air-fluid levels, it has been shown to be unhelpful as a diagnostic aid in patients with intussusception (3,8). The benefit of left lateral decubitus positioning is that air in the transverse colon is directed toward the ascending colon and cecum, thereby improving visualization of this key portion of the colon in this patient population. When the ascending colon and cecum are confidently and completely delineated (Figs 2, 3), ileocolic intussusception is unlikely (98% in our investigation). Although many intussusceptions are located in the transverse colon and although a mass is often visible on the supine radiograph, the movement of air into the ascending colon and cecum often outlines the intussusceptum when it is located in the proximal transverse colon or when it has not reached the transverse colon and is located within the ascending colon or cecum, thus expediting subsequent care (Fig 4).

Unlike previous investigations that used KUB with upright views (3,8), our results indicate that the KUB plus left-side-down decubitus set is helpful in the diagnosis and care of patients suspected of having intussusception. Initial radiographs provide important information in patients presenting with abdominal findings and important management information in those with intussusception, such as the presence of high-grade small-bowel obstruction and the presence or absence of free air. When radiographs unequivocally delineate an intussusception, these patients may be referred directly to air reduction enema without subsequent US and additional delay. Conversely, when the proximal colon is unequivocally delineated by air and stool at radiography, consideration of other diagnoses or observation may be indicated. US evaluation is most valuable for patients with equivocal radiographs or for those with negative radiographs but continued high clinical suspicion for intussusception.

Earlier investigations have shown a wide variability in the reported accuracy of radiography in the evaluation of patients suspected of having intussusception. Eklof and Hartelius (9) reviewed 100 patients with and 100 patients without intussusception; these patients were evaluated with radiographs obtained with the following views: KUB, left-side-down decubitus with horizontal beam, and left-side down decubitus with vertical beam. Although Eklof and Hartelius did not include a statistical analysis, they observed that scant abdominal gas, diminished colonic feces, and visualization of the intussusceptum allowed an 89% positive rate at subsequent barium enema examination of patients with intussusception and allowed exclusion in 74% of patients without intussusception. These figures are slightly better than the respective 74.1% and 58.1% in our investigation.

Although Eklof and Hartelius (9) were able to make those diagnoses, review of their data shows a large overlap in the findings between the two groups. The exception was a discernible mass lesion, which was present in 52 patients with intussusception and three without intussusception. The major characteristics—paucity of small-bowel gas and of colonic feces—were present, respectively, in 89% and 82% of patients with intussusception and in 45% and 19% of patients without intussusception. In 11% and 19% of patients with intussusception, the bowel gas pattern and the fecal distribution, respectively, were unremarkable. These authors did not address identification of the cecum, although this is widely recognized as one of the most important discriminatory parameters in assessment of ileocolic intussusception (1,2,8,10).

Meradji et al (10) reported a 90% sensitivity and a 90% specificity for identification of intussusception with use of a weighting system of five radiographic parameters. However, these investigators did not describe the views obtained, and their results have not been duplicated in subsequent reviews, perhaps because some of the parameters, such as decreased gas in the jejunum and decreased feces in the colon, are subjective and are subject to high interobserver disagreement. These authors visualized an intussusceptum in 71% of patients with intussusception and in 6% of the control group. We were able to directly visualize the intussusceptum itself in 34.5% of patients with use of the KUB view alone and in 36.2% with use of the KUB plus decubitus views. Our findings are more in line with the rate of identification reported by others (Hernandez et al [3] reported 29%; Sargent et al [8] reported 42% with the supine view and 32% with the upright view). This is also in keeping with the data in the 1975 review by Williams (11), which indicates that the abdominal series is expected to depict intussusception in one-third of the cases and to show normal or nonspecific findings in the remaining two-thirds.

In more recent investigations, authors have described less success in radiographic evaluation of intussusception. Hernandez et al (3) retrospectively evaluated 80 patients with proved intussusception by using KUB and upright views. The triad of an intracolonic mass, obstruction, and paucity of gas in the right lower quadrant was seen in only one of the 80 patients, a normal bowel gas pattern was present in 24% of patients, and radiographs were diagnostic of intussusception in only 29% of patients. These investigators concluded that patients suspected of having intussusception require further studies and that radiographs are not diagnostically helpful.

Sargent et al (8) showed equivocal results for 53% of abdominal radiographs obtained with supine views and 62% of erect radiographs. They found that the most helpful signs were a discrete soft-tissue mass and sparse colonic gas. Among their patients with intussusception, radiographs were diagnostic in only 27 of 60 cases (45%). The percentage of studies with equivocal results reported by Sargent et al (53%) was lower than the percentage we found with the supine view alone (63.8%). However, the percentage of equivocal examinations in our investigation significantly improved with the addition of the left-side-down decubitus view (from 63.8% to 32.6%; P < .001), compared with that of Sargent et al with an upright view (56%). In comparison with these investigators, our ability to accurately diagnose intussusception was higher with supine views (60.3%, or 35 of 58 studies) and much higher with the addition of decubitus views (74%, or 48 of 58 studies), compared with the results of Sargent et al (42%) and Hernandez et al (29%).

The limitations of our investigation include its retrospective nature. We attempted to eliminate subjectivity by clearly defining end-point parameters, such as identification of the ascending colon and cecum, rather than using more general observations, such as diminished bowel gas or fecal content. However, some element of subjectivity must be considered in identification of a specific viscus (eg, cecum vs sigmoid colon) within protean bowel gas patterns; hence individual negative or positive parameters for intussusception, such as identification of the cecum, do not show a 100% correlation with a positive or a negative diagnosis of intussusception in every case.

In conclusion, we have found that the left-side-down decubitus radiograph allows incremental improvement in the radiographic diagnosis of intussusception. These findings suggest that this radiograph should replace the upright radiograph in the radiographic evaluation of the patient presenting with clinical concern for ileocolic intussusception.

ADVANCES IN KNOWLEDGE

The addition of the left lateral decubitus view to the KUB series increases the percentage of studies considered diagnostically determinate for intussusception from 36.2% to 67.4%.

Sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of intussusception significantly improve with the addition of the left lateral decubitus view to the KUB series.

IMPLICATION FOR PATIENT CARE

Addition of the decubitus view to the abdominal series in place of the upright view provides incremental information and allows improved care of patients suspected of having ileocolic intus-susception.

Abbreviations

KUB = kidney, ureter, bladder

Author contributions: Guarantors of integrity of entire study, R.L.H., J.H.K.; study concepts/study design or data acquisition or data analysis/interpretation, all authors; manuscript drafting or manuscript revision for important intellectual content, all authors; approval of final version of submitted manuscript, all authors; literature research, R.L.H., M.H., J.H.K.; clinical studies, R.L.H., M.H., J.H.K.; statistical analysis, C.Y.; and manuscript editing, all authors

Authors stated no financial relationship to disclose.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Center for Research Resources (grant 1 UL1 RR024975).

References

- 1.del-Pozo G, Albillos JC, Tejedor D, et al. Intussusception in children: current concepts in diagnosis and enema reduction. RadioGraphics 1999;19:299–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daneman A, Navarro O. Intussusception. I. A review of diagnostic approaches. Pediatr Radiol 2003;33:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez JA, Swischuk LE, Angel CA. Validity of plain films in intussusception. Emerg Radiol 2004;10:323–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wayne ER, Campbell JB, Burrington JD, Davis WS. Management of 344 children with intussusception. Radiology 1973;107:597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White SJ, Blane CE. Intussusception: additional observations on the plain radiograph. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982;139:511–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bisset GS 3rd, Kirks DR. Intussusception in infants and children: diagnosis and therapy. Radiology 1988;168:141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verschelden P, Filiatrault D, Garel L, et al. Intussusception in children: reliability of US in diagnosis—a prospective study. Radiology 1992;184:741–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sargent MA, Babyn P, Alton DJ. Plain abdominal radiography in suspected intussusception: a reassessment. Pediatr Radiol 1994;24:17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eklof O, Hartelius H. Reliability of the abdominal plain film diagnosis in pediatric patients with suspected intussusception. Pediatr Radiol 1980;9:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meradji M, Hussain SM, Robben SG, Hop WC. Plain film diagnosis in intussusception. Br J Radiol 1994;67:147–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams HJ. Intussusception: facts, fallacies and practicalities. Minn Med 1975;58:140–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]