Abstract

The localized structural abnormalities that arise during vasculogenesis, angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis, the developmental processes which give rise to the adult vasculature, are collectively termed vascular anomalies. The last 2 years have seen an explosion of studies that underscore paradominant inheritance, the combination of inherited changes with somatic second-hits to the same genes, as underlying rare familial forms. Moreover, local, somatic genetic defects that cause some of the common sporadic forms of these malformations have been unraveled. This highlights the importance of assessing for tissue-based genetic changes, especially acquired genetic changes, as possible pathophysiological causes, which have been largely overlooked except in the area of cancer research. Large-scale somatic screens will therefore be essential in uncovering the nature and prevalence of such changes, and their downstream effects. The identification of disease genes combined with exhaustive, precise clinical delineations of the entire spectra of associated phenotypes guides better management and genetic counseling. Such a synthesis of information on functional and phenotypic effects will enable us to make and use animal models to test less invasive, targeted, perhaps locally administered, biological therapies.

INTRODUCTION

Vascular anomalies, localized structural defects of the vasculature, are broadly divided into vascular tumors and vascular malformations (1). Hemangiomas (Fig. 1A) account for a majority of the tumors, and are characterized by a rapidly proliferative phase, followed by a longer involuting phase, during which they spontaneously regress. Although the molecular basis of hemangiomas is unknown, germline heterozygous single nucleotide changes in VEGFR2/KDR and the integrin-like receptor TEM8/ANTXR1 were found to be enriched in affected individuals (2). The resulting perturbation of the VEGF signaling pathway, as well as the effects of inhibiting it, can now be tested in a new mouse model, which recapitulates these tumors with the use of hemangioma-derived (stem) cells (3).

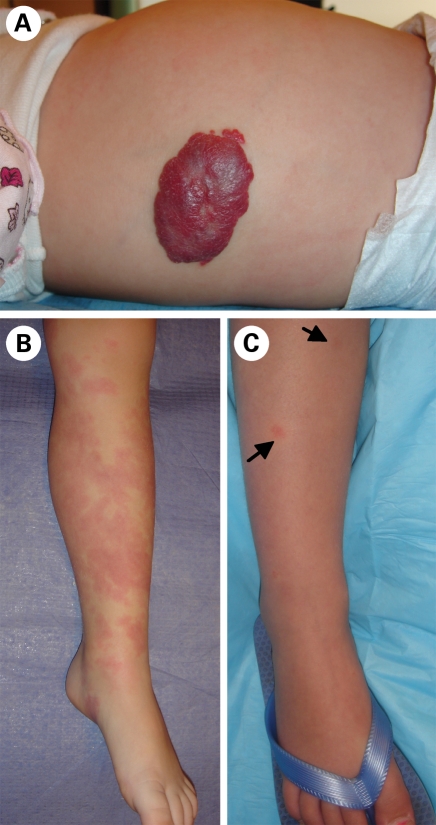

Figure 1.

Vascular tumors and malformations (A) proliferating hemangioma, a benign tumor of infancy. (B) Extensive sporadic CM, distinct from (C) small, multifocal CMs with pale halo, characteristic of CM–AVM.

The more rare vascular malformations are broadly divided according to the component they affect: capillary, venous, arterial, lymphatic or combined malformations (4). Typically congenital, they grow proportionately with the individual, and do not regress spontaneously. They can vary widely in size, number and localization, with inherited forms typified by multiple lesions, and sporadic forms by single, sometimes extensive lesions. Vascular malformations can also occur in the context of syndromes (5). Table 1 summarizes progress made in elucidating the genetic bases of several malformations, predominantly the inherited forms. These have been reviewed in detail in (6). We focus on significant recent advances that have shed new light on disease causation.

Table 1.

Summary of identified genetic bases of vascular malformations / syndromes with a major vascular malformation component

| Malformation | Characteristics | Mode of inheritance | Locus | Gene | Mutations | Expression | Functions/Pathways | Interactors/Effectors/Targets | Mouse Models | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capillary anomalies | |||||||||||

| Capillary Malformation (CM) | Dilated/increased capillary channels Flat red cutaneous “port-wine stains” | Sporadic | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Capillary Malformation-Arteriovenous Malformation (CM-AVM) | Small multifocal CMs, AVM/AVF/PWS (30%) 80% AVM/AVF in head, neck | Autosomal dominant | 5q13-22 | CMC1 | RASA1 | Loss-of-function | Ubiquitous? | Ras/MAPK inhibition Cell motility, survival | PDGFβ, EGFR, FGFR, EphB2,B4 p190RhoGAP | Mosaic Rasa1-/- | (7–9, 11) |

| Progressive Patchy Capillary Malformation/Angioma Serpiginosum | Dilated/increased thick-wall capillaries Sub-epidermal. Cutaneous rash, Hair, nail dystrophy; Esophageal papillomatosis | X-linked Skewed X-inactivation | Xp11.23 | PORCN? Also includes: SLC38A5, FTSJ1 EBP OATL1 RBM3 WDR13 SSX |

Locus deletion | – | – | – | – | (13,14) | |

| Cerebral Cavernous Malformation (CCM) | Dilated channels Lack EC tight junctions Brain, spinal cord, retina, cutaneous Headaches, seizures, hemorrhage |

Sporadic | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Autosomal dominant | 7q11-22 | CCM1 | KRIT1 | Loss-of-function 3 Somatic 2nd hits | Neural, vascular Neurons, astrocytes epithelial cells, ECs |

Adaptor protein Integrinβ1 pathway Arterial specification Cell adhesion, migration |

ICAP-1α, microtubules Rap1, SNX17, CCM2 & 3 |

Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- | (21–26, 101, 102) | ||

| 7p13 | CCM2 | malcavernin | Loss-of-function 2 Somatic 2nd hits | Neural, vascular Neurons, astrocytes |

Adaptor protein Osmosensing Overlap with above |

MEKK3, Rac, CCM1 & 3 | Ccm2+/- | ||||

| 3q26.1 | CCM3 | PDCD10 | Loss-of-function 2 Somatic 2nd hits | Neural, vascular | Apoptosis? Overlap with above |

CCM1 & 2 | |||||

| 3q26.3-27.2 | CCM4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Venous anomalies | |||||||||||

| Glomuvenous malformation (GVM) | Enlarged venous channels, rounded vSMCs (“glomus” cells) Raised hyperkeratotic nodules Skin, rare in mucosa |

Autosomal dominant | 1p21-22 | VMGLOM | GLMN | Loss-of-function One somatic 2nd hit | Vascular:SMCs | SMC differentiation, Protein synthesis/degradation TGFβ, HGF pathways |

FKBP12, c-Met, p70S6K, Cul7 | – | (50, 51) |

| Venous Malformation (VM) | Enlarged venous channels, flat EC, sparse vSMCs Small blebs to soft bluish masses Skin, mucosa, underlying tissue/organs |

Autosomal dominant (1-2%):VMCM | 9p21 | VMCM1 | TIE2/TEK | Gain-of-function One (loss-of-function) somatic 2nd hit | Vascular; ECs, hematopoietic cells | Tyrosine kinase receptor EC migration, proliferation, survival SMC-recruitment, Vascular sprouting, maturation, stability Hematopoietic quiescence |

Ang1, 2, & 4 (ligands) α5β1 integrin, TIE1 PI3K/Akt, survivin, FAK, RhoA Rac1, eNOS, Dok-R, Grb2,7,14, Ras, ERK1/2, p38MAPK, STATs, VE-PTP | – | (35, 49, 103) |

| Sporadic VM (98%) | TIE2/TEK | Somatic, Gain-of-function | |||||||||

| Lymphatic anomalies | |||||||||||

| Lymphatic Malformation (LM) | Dilated micro or macrocystic lymphatic channels with clear fluid Skin-colored bumps Skin, underlying tissue/bones |

Sporadic | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Primary Lymphedema (LE) Primary Congenital LE (Nonne-Milroy disease) Hydrops |

Defective lymphatic drainage Extensive swelling, often of extremity Present at birth; hypoplasia LE below knees |

Dominant/recessive | 5q35.3 | PCL1 | VEGFR3/FLT4 | Loss-of-function | Vascular; Lymphatic ECs | Tyrosine kinase receptor EC proliferation, migration, survival Angiogenic sprouting, network formation Lymph-vessel formation | VEGF-C, D (ligands), VEGFR2 Shc, Grb2, PLCg/PKC, p42/44MAPK PI3K/Akt | Chy | (74, 75, 104, 105) |

| Sporadic | VEGFR3/FLT4 | De novo, loss-of-function | |||||||||

| LE-Distichiasis (LD) Hydrops | LE with accessory fine eyelashes from meibomian glands Ptosis or yellow nail syndrome in some Hyperplasia; LE can be above knees | Autosomal dominant, | 16q24.3 | LD | FOXC2 | Loss-of-function | Mesenchymal, endothelial | Transcription factor. Arterial cell specification Angiogenesis, Vascular remodeling VEGF, Notch pathways Insulin, TGFβ signaling | Smad3, Su(H) Inhibition of: PDGFβ secretion Induction of: Ang2, integrinβ3, fibronectin, CXCR4, Dll4, Hey2 | (88, 89, 104) | |

| Sporadic | FOXC2 | De novo, loss-of-function | |||||||||

| Hypotrichosis-LE-Telangiectasia (HLT) Hydrops | LE with sparse hair, cutaneous telangiectasias | Dominant/recessive | 20q13.33 | HLT | SOX18 | Loss-of-function 1 De novo mosaic in parents | ECs; sites of vasculogenesis & angiogenesis Cardiovascular | Transcription factor Arteriovenous specification Lymphatic EC differentiation | MEF2C Induction of: Prox1, VCAM-1 | Ragged | (95, 104, 106, 107) |

| LE-Hereditary Cholestasis (Aagenaes syndrome) | LE with neonatal choleostasis | Autosomal recessive | 15q | LCS1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | (108) |

| Primary Congenital Resolving Lymphedema (PCRL) | LE, gradual resolution post-puberty | Autosomal dominant | 6q16.2-22.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | (85) | |

| Arterial/Combined Malformations | |||||||||||

| Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM) | Artery-vein connections in nidus, fibrosis | Sporadic | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) or Rendu-Osler-Weber (ROW) | Epistaxis, Cutaneous telangiectasias (dilated post-capillary venules) AVMs in brain/lungs/GI tract HHT1: >cerebral, pulmonary AVMs HHT2: >hepatic AVMs |

Autosomal dominant | 9q33-34 | HHT1 | ENG | Loss-of-function | Vascular; Angiogenic sites ECs, monocytes, hematopoietic cells | Type III TGFβ receptor TGFβ family signal modulation EC hypoxia-survival, migration, proliferation Vascular organization Monocyte-macrophage transition Myogenic differentiation Erythroid development |

TGFβ, activins, BMPs (ligands) TGFβRII, TGFβRIs (ALK1, 5) MAPK, β−arrestin2, Tctex2β Smad1 |

Eng+/- | (109, 115) |

| 12q11-14 | HHT2 | ALK1 | Loss-of-function | Vascular; ECs, epithelial- mesenchymal sites | Type I TGFβ receptor TGFβ family (-independent) signal transduction EC migration, proliferation |

TGFβ, activins, BMPs (ligands) TGFβRII, Endoglin Smad1, 5, 8, Id1 |

Acvrl+/- | ||||

| 5q31.3-32 | HHT3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| 7p14 | HHT4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Juvenile Polyposis HHT (JPHT) | HHT with juvenile polyposis (polyps, predisposition to tumors) | Autosomal dominant | 18q21.1 | JPHT | SMAD4 | Loss-of-function | Ubiquitous | Intracellular mediator, TGFβ signaling | TGFβ, activins, BMPs (ligands) Smad 2, 3; SNIP1, Sp1,MSG1, βcatenin, βtubulin, etc | Smad4+/- (polyps, tumors) | (116, 117) |

“References” combine primary references (initial gene identification, mouse models) with reviews. “Mouse Models”include alterations of causative genes which recapitulate respective malformations.

CAPILLARY MALFORMATIONS

Capillary malformations (CM; MIM 163000) are flat, reddish ‘port-wine stains’ of unknown etiology, which typically occur as sporadic, unifocal, cutaneous lesions consisting of dilated capillary channels (Fig. 1B) (4). We recognized a distinct sub-entity, capillary malformation–arteriovenous malformation (CM–AVM; MIM 608354), which is characterized by autosomal-dominantly inherited, small, multifocal CMs, often accompanied by a pale halo (Fig. 1C) (7,8). These lesions are caused by loss-of-function mutations in the RASA1 gene (9), encoding the Ras GTPase activating protein p120RasGAP, with a high penetrance (98%) (8). We also observed that ∼30% of the time, they are accompanied by deeper, more dangerous fast-flow anomalies: arteriovenous malformations, arteriovenous fistulas (AVM/AVF) or Parkes Weber syndrome (PWS) (8). Moreover, 80% of the AVM/AVFs lesions are located intra- or extra-cranially, in the head and neck regions (8), which is distinct from the often visceral fast-flow anomalies seen in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). Vein-of-Galen aneurysmal malformation is now also recognized amongst the fast-flow lesions caused by RASA1 mutations (8). Thus, brain MRI is indicated for patients suspected to have CM–AVM, even if 70% of patients only have CMs (8). This phenotypic heterogeneity indicates a requirement for additional modulatory events, possibly including somatic second-hits to RASA1. Such a paradominant mode of inheritance, suggested to account for the incomplete penetrance, and focal, heterogeneous lesions of autosomal dominantly inherited vascular malformations (10), would fit the localized vascular defects observed in Rasa1−/− -mosaic mice (11) (Fig. 1).

Angioma serpiginosum

Angioma serpiginosum or progressive patchy CM (12), a rare, X-linked dominant congenital skin disorder with strongly skewed X-inactivation, was linked to a Xp11.3-Xq12 locus (13). Malformations consist of an increased number of dilated, thick-walled capillaries, located sub-epidermally, appearing as a rash along Blaschko's lines, along with mild hair and nail dystrophy, and esophageal papillomas (13). A 112 kb deletion was identified in the affected individuals, at Xp11.23 (14), containing at least five genes. One of these is PORCN, deletions or mutations in which cause sporadic and inherited focal dermal hypoplasia (or Goltz–Gorlin syndrome), characterized by dermal hypoplasia or atrophy, cutaneous or esophageal papillomas, and eye, hand or skeletal anomalies (15,16). The overlap in symptoms raised the possibility that the two syndromes are allelic (14). Strong, post-zygotic somatic changes, which may not be tolerated when inherited, can cause severe sporadic syndrome, while weaker, heritable changes mediate the milder familial trait: a recurrent theme that emerges strongly in this review.

CEREBRAL CAVERNOUS MALFORMATION (CCM)

The cerebral lesions of CCM (MIM 116860) are characterized by dilated channels with endothelial cell (EC) layers that have defective tight junctions, and a dense collagen matrix without intervening brain parenchyma (17,18). They occur in the brain, retina and spinal cord, and can cause headaches, seizures and cerebral hemorrhage. They are sometimes accompanied by cutaneous lesions, which are often hyperkeratotic (19,20, Labauge, 2007 no. 50). Three genes carrying inherited loss-of-function mutations were identified in succession (reviewed in 21): CCM1 (KRIT1; (22,23)), CCM2 (malcavernin/MGC4607; (24)) and CCM3 (PDCD10; (25)), with a fourth locus suggested by linkage to 3q26.3–27.2 (26). Interestingly, mutations tend to be absent in individuals established to have sporadic, unifocal lesions (27–29). This may be partially due to the use of exon-scanning methods to detect single nucleotide mutations and small insertions/deletions, which are increasingly being complimented with techniques such as multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) assay to demonstrate larger intragenic alterations (30–32). When combined, mutations in the known genes are identified in >90% of probands with at least 1 affected relative, yet in only ∼60% of ‘isolated’ cases with multifocal lesions (33,34). Some of the latter may represent a sporadic, multifocal entity with a somatic genetic basis in the CCM genes, similar to what has been demonstrated for sporadic multifocal venous malformations (VMs) and TIE2 (35).

Progress in the area of CCM genetics exemplifies the fact that molecules that interact within the same pathway are good candidates to cause similar phenotypes: In situ hybridization showed similar patterns of expression for the three CCM transcripts through much of murine pre- and post-natal development and adulthood (36), and lack of either CCM1 or CCM2 was shown to result in progressive dilation of vessels in zebrafish (37). All three adaptor proteins were indeed found to interact with each other, probably through CCM2, to form part of a complex that also contains MEKK3, the small GTPase RAC1 and the β1-integrin binding protein ICAP-1α (34,38–41), indicating that the complex acts downstream of integrin signaling, and possibly in reactions to osmotic stress, through the p38MAPK pathway (42). The debated interaction of KRIT1 with the small GTPase Rap1 (43,44) has been recapitulated in ECs, where it may regulate cell–cell junctions (45).

Paradominant inheritance is now becoming evident in CCM. Somatic second-hits were identified in affected ECs from a few lesions, in each of the three CCM genes. They were all biallelic to the inherited change in the same gene (46,47). Moreover, antibodies generated against each of the CCM proteins showed that germline heterozygous mutations are accompanied by a complete loss of the mutated gene-products in affected ECs, indicating that somatic alterations most likely occur within the same gene (48), rather than trans-heterozygously. These data underscore the likelihood of somatic (epi)genetic changes being involved in sporadic unifocal and multifocal lesions.

VENOUS ANOMALIES

Venous anomalies represent a significant fraction of patients seen at centers specialized in treating vascular malformations, as they can cause pain, and affect appearance or organ function, due to their size, localization and expansion (reviewed in 4). VMs account for 95% of these anomalies. They are histologically characterized by enlarged venous channels, lined with a single, flattened layer of ECs, and sparse, irregularly distributed vSMCs (49). While predominantly sporadic (>98%), 1–2% of the time they occur as an autosomal dominant inherited trait, termed cutaneomucosal venous malformation (VMCM; MIM 600195) (50).

The autosomal dominantly inherited glomuvenous malformations (GVMs; MIM 138000) make up the remaining 5% of venous anomalies (Fig. 2A) (6). These superficial, multiple raised or plaque-like lesions are caused by loss-of-function mutations in glomulin (GLMN/FAP68; (51)), which derails vSMC differentiation towards rounded ‘glomus’ cells, which are observed around distended vascular channels. More than 30 mutations have been identified across the length of the gene in >100 families, and 11 changes account for >80% of patients, making them good primary screen candidates (52–54, Brouillard et al., unpublished data). A resected GVM provided the first proof of paradominant inheritance of a vascular anomaly, a 5 base-pair intra-glomulin deletion specifically in the tissue (51). The identification of the genetic bases of GVM and VMCM also allowed for their delineation as distinct entities, therefore optimizing their clinical management (50,55). In addition, characterization of their pathophysiology paved the way for the identification of the localized genetic defects that cause a large fraction of the most prevalent form, sporadic VMs.

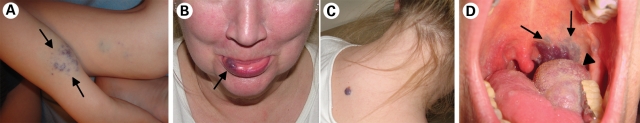

Figure 2.

The many faces of venous anomalies. Identification of their genetic bases has helped distinguish between (A) GVM, caused by loss-of-function of glomulin (GLMN), (B and C) VMCM, caused by inherited gain-of-function changes in TIE2/TEK, and (D) sporadic venous malformations, caused by somatic gain-of-function mutations in TIE2/TEK.

Cutaneomucosal venous malformations (VMCM)

Inherited VMCM, typified by the appearance of small, multifocal muco-cutaneous lesions (Fig. 2B and C), has been shown to be mediated by two mutations in the TEK gene, which encodes the tyrosine kinase receptor TIE2 (49,56). Six additional intracellular, hyperphosphorylating mutations have now been identified, with weak-to-strong ligand independent receptor hyperphosphorylation effects in vitro (V. Wouters et al., Manuscript in submission). The R849W change is the most common, occurring in ∼60% of families (V. Wouters et al., Manuscript in submission). Significantly, we identified a somatic second-hit in a VMCM tissue from an individual with the inherited R849W change. It consisted of a deletion of a large portion of the extracellular Ig2 ligand-binding domain of wild-type TIE2, resulting in a loss-of-function (35). The presence of wild-type TIE2 would therefore seem to provide a protective effect against the aberrant R849W, which may be able to cause lesions only when operating exclusively. The nature of this protective effect is unknown, as is the pathogenic mechanism of the common mutation. R849W has an increased pAkt and p52Shc-dependent anti-apoptotic effect (57), which may allow for the survival of ECs despite erratic SMC support. The mutation does not seem to affect cell proliferation or migration, but increases instability of tube-formation by HUVECs in vitro (58). R849W does more than chronically activate pathways normally activated by the wild-type receptor upon ligand-stimulation: while wild-type TIE2 can activate STAT3 (and STAT5 in HEK293 cells, but not HUVECs), only R849W chronically activates STAT1, in a JAK-dependent manner (58,59). Ang1-stimulation of TIE2 has recently been found to induce the expression of Apelin, a ligand for the G-protein-coupled receptor APJ, in ECs. This system in turn regulates the caliber of blood vessels (60), making it an attractive, as yet untested candidate pathway through which the dilated channels in VMs may occur.

Sporadic venous malformation (sporadic VM)

The majority of VMs are sporadic in nature, and characterized by extensive, unifocal lesions of variable size (Fig. 2D) (4), which can infiltrate deep into underlying tissues (61). Coagulation abnormalities are specifically associated with VMs, and seem to correlate with increased size and the presence of phleboliths (62, Dompmartin et al., submitted for publication). Their prevalence, and the significant morbidity associated with them, made the identification of their etiopathogenic basis a priority. We recently discovered that somatic mutations in TIE2 cause roughly 50% of sporadic VMs (35). The intracellular hyperphosphorylating mutations, identified in frozen VM-derived DNA, were absent in blood samples from the same patients. Close to 80% are accounted for by one mutation: L914F, which is also the only change that occurs alone. The remainder consists of pairs of double or compound mutations that always occur together in cis (on the same allele), and may preferentially predispose to rare, multifocal sporadic VMs (35). Despite its frequent recurrence in sporadic VMs, L914F has never been observed as a germline change in VMCM, suggesting it to be too deleterious for survival when inherited. Conversely, the common inherited R849W, which needs a second-hit to eliminate the protective wild-type allele, has not been identified in sporadic VM, implicating weaker effects.

The frequent VMCM-associated R849W and sporadic VM-associated L914F have overlapping, yet distinct effects on TIE2 localization, and translocation in response to ligand (35). Receptor localization is important for TIE2 function: ligand-induced translocation of TIE2 to cell–cell edges versus cell–matrix interfaces, results in the preferential recruitment and activation of distinct sets of effectors, which can have differential downstream effects (63,64). Thus, abnormal compartmentalization of mutant TIE2 receptors in the absence or presence of ligand could give them access to inappropriate signaling complexes.

It is possible that as-yet undetected mutations within TIE2 are responsible for the 50% of sporadic VMs that remain unaccounted for. Other players within the TIE2 pathway, especially those proximal to the receptor, could also be expected to yield similar, specific phenotypes. These include TIE1, which can heterodimerize with TIE2 (65,66); the Ang ligands (65–71); and VE-PTP, the vascular endothelial phosphatase, which can specifically regulate TIE2 activation (72,73).

LYMPHATIC ANOMALIES

Lymphatic malformations (LMs) are focal or extensive lesions made up of dilated lymphatic channels, which are disconnected from the lymphatic system. They are filled with clear fluid, with no blood flow through them (4). The etiology of primary LMs, which have only been recorded to occur sporadically, is not known. However, genetic studies on lymphedema have brought to light factors that are critical to lymphatic development and function in man.

Primary lymphedema

Lymphedema (LE) is characterized by diffuse, extensive swelling caused by defective lymphatic drainage. It usually involves the lower extremities, and can be associated with lymph node fibrosis. Primary lymphedema can be sporadic or inherited as an incompletely penetrant, dominant or recessive disorder (4). Depending on the age of onset, the spectrum of phenotypes can be divided into type I congenital lymphedema, usually present at birth; type II praecox (Meige disease), appearing between puberty and age 35; and lymphedema tarda after this point (4). Mutations in three genes have been identified to cause primary LE.

An autosomal-dominantly inherited form of congenital lymphedema, Nonne–Milroy disease (MIM 153100), is mediated by loss-of-function mutations in conserved residues in the two intracellular tyrosine kinase domains of VEGFR3/FLT4 (74–76), the receptor for VEGF-C and -D (77,78). It predominantly affects the lower limbs below the knees (>90%), and is sometimes (in<30%) accompanied by hydrocele in men, prominent veins, cellulitis, upturned toenails or papillamatosis (79). Intrauterine pleural effusion and hydrops fetalis have been observed in rare pregnancies in these families (80,81). VEGFR3 has also been found to be mutated de novo in patients with sporadic forms of congenital lymphedema (81–83). Hence, family history, considered a hallmark of Milroy disease, is no longer a criterion for VEGFR3-mediated lymphedema. Moreover, whereas Milroy described dominant inheritance of congenital primary lymphedema, true of all reported familial cases with VEGFR3 mutations, we identified a specific VEGFR3 amino-acid change in a family with recessively inherited lymphedema (84). Unlike the dominantly inherited mutants, the latter diminishes, but does not abolish, VEGFR3 phosphorylation in vitro. Homozygosity for this hypomorphic allele is thus required in family members to express the phenotype.

Other genes may play a role in LE. In one family, a low-penetrant, autosomal dominant form of congenital lymphedema, which progressed through childhood and resolved gradually after puberty (primary congenital resolving lymphedema), was linked to a 6q16.2-q22.1 locus (85). Rare changes have been reported in additional genes including neuropilin-2 (NRP-2, which can bind VEGF-C and -D, and is co-immunoprecipitated with VEGFR3), SOX17, VCAM1, HGF and its receptor c-MET (86,87). Whether they represent disease-associated mutations, or simply rare genetic variants, however, remains to be assessed.

Loss-of-function mutations in the forkhead transcription factor FOXC2 have been identified in families with late onset lymphedema (Meige disease; MIM 1532000) in association with distichiasis, sometimes accompanied by ptosis, or yellow nail syndrome (88–90). The molecule can regulate angiogenesis and vascular remodeling, through direct control over the expression of genes including Ang2 (in adipose tissue; (91)), extracellular matrix interactors such as the integrins and fibronectin (92), and the VEGF/Notch pathway targets Dll and Hey2 (93). Another target is the inhibition of PDGFβ secretion, which in the context of loss of FOXC2 function, becomes overproduced leading to increased vSMC coverage of lymphatic channels, and their dysfunction (94): another example of the important ongoing cross-talk and balance between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in lymphatic and vascular channels.

Hypotrichosis–lymphedema–telangiectasia syndrome (HLTS; MIM 607823) is associated with sparse hair and skin telangiectasias, and can be mediated by the transcription factor SOX18, a very early lymphatic marker (95,96, reviewed in 97). SOX18 can regulate PROX1, central in lymphatic EC-induction (96). Both dominant, nonsense mutations with likely dominant-negative effects, as well as recessive, homozygous subsitutions in the DNA-binding domain have been identified (95). While SOX18 seems to have redundant roles with SOX7 and SOX17 in arterio-venous specification (98–100), it is critical to lymphatic development, as evidenced by a complete block in lymphatic EC differentiation from the cardinal veins of Sox18−/− mice. This results in a genetic background (C57Bl/6)-specific severe edema and homozygous lethality, and milder edema in heterozygotes, absent on the mixed 129/CD1 strain, indicating the importance of epistasis in this process (96).

The LE-genes may also account for a significant proportion of unexplained sporadic hydrops fetalis, as evidenced by an initial screen of 12 patients, which revealed that two had VEGFR3 mutations, while another had a FOXC2 mutation (83). The remaining 75% may also be genetic in origin, due to germline or acquired mutations in as-yet unknown lymphangiogenic factors.

CONCLUSION

As evidenced by these rapidly expanding areas of research, much progress has been made on identifying genes and pathways responsible for inherited vascular anomalies. Most follow autosomal-dominant inheritance, and are characterized by multifocal, small lesions which tend to increase in number with time. Increasing data on GVMs and CCMs requiring bi-allelic, complete local loss-of-function of their mutated genes, are complemented by the more complex situation in VMCM, where a ‘weak’ inherited gain-of-function is combined with a loss-of-function somatic second hit to TIE2. Even in the absence of a detailed picture of pathogenic mechanisms, these discoveries demonstrate a genetic, albeit partly somatic, origin for the localized lesions. Given the relative prevalence of the sporadic forms, the most immediate challenge is the elucidation of the molecules and pathways (and therefore, potential therapeutic targets) involved in their etiology. De novo or purely somatic mutations in the genes that cause rare, inherited disorders may be the most attractive candidates, as demonstrated by TIE2 mutations in ∼50% of VMs. In other cases, defects in interacting proteins may lead to similar defects. Capturing them requires the use of appropriate starting material: the inclusion of lesion-derived material in addition to blood-DNA. Methods to reduce tissue-heterogeneity (such as laser-capture) may be needed, as the presence of numerous wild-type cells in resected tissues hinders the identification of somatic mutations in a small number of cells of a specific phenotype. RNA-based screens can also decrease heterogeneity, by excluding sequences present in DNA of all cell-types, while detecting only those that are expressed in lesions. Large genomic alterations will need to be screened for as well, with techniques such as MLPA, or high-density SNP and copy number genotyping arrays. Finally, detailed investigations of the spectrum of phenotypes associated with identified genes are critical to gene discovery, clinical care and genetic counseling. In vivo models that recapitulate these disease phenotypes are invaluable in evaluating the safety and efficacy of potential therapies. Most homozygous deletions of the molecules that have been identified result in embryonic lethality, while heterozygotes typically lack any phenotype. This makes the use of inducible, cell-type-specific knock-outs (or knock-ins, in the case of gain-of-function mutations) essential in studying the pathological processes that give rise to vascular anomalies.

FUNDING

We received support from the Interuniversity Attraction Poles initiated by the Belgian Federal Science Policy, network 5/25 and 6/05; Concerted Research Actions (A.R.C.)—Conventions Nos 02/07/276 and 7/12-005 of the Belgian French Community Ministry; the National Institute of Health, Program Project P01 AR048564-01A1; EU FW6 Integrated project LYMPHANGIOGENOMICS, LSHG-CT-2004-503573; the FNRS (Fonds national de la recherche scientifique) (M.V. received ‘Maître de recherches honoraire du FNRS’).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Ms Liliana Niculescu for secretarial help.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mulliken J.B., Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1982;69:412–422. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jinnin M., Medici D., Park L., Limaye N., Liu Y., Boscolo E., Bischoff J., Vikkula M., Boye E., Olsen B.R. Suppressed NFAT-dependent VEGFR1 expression and constitutive VEGFR2 signaling in infantile hemangioma. Nat. Med. 2008;14:1236–1246. doi: 10.1038/nm.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan Z.A., Boscolo E., Picard A., Psutka S., Melero-Martin J.M., Bartch T.C., Mulliken J.B., Bischoff J. Multipotential stem cells recapitulate human infantile hemangioma in immunodeficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2592–2599. doi: 10.1172/JCI33493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boon L.M., Vikkula M. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th edn. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing; 2007. Vascular malformations. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulliken J.B., Young A.E. Vascular Birthmarks: Hemangiomas and Malformations. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brouillard P., Vikkula M. Genetic causes of vascular malformations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16(Spec No. 2):R140–149. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Vikkula M. RASA1: variable phenotype with capillary and arteriovenous malformations. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2005;15:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Revencu N., Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Enjolras O., Cordisco M.R., Burrows P.E., Clapuyt P., Hammer F., Dubois J., Baselga E., et al. Parkes Weber syndrome, vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation, and other fast-flow vascular anomalies are caused by RASA1 mutations. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:959–965. doi: 10.1002/humu.20746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eerola I., Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Burrows P.E., Dompmartin A., Watanabe S., Vanwijck R., Vikkula M. Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation, a new clinical and genetic disorder caused by RASA1 mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:1240–1249. doi: 10.1086/379793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Vikkula M., Watkins H., Seidman J., Olsen B.R., Warman M.L. Assignment of a locus for dominantly inherited venous malformations to chromosome 9p. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994;3:1583–1587. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.9.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henkemeyer M., Rossi D.J., Holmyard D.P., Puri M.C., Mbamalu G., Harpal K., Shih T.S., Jacks T., Pawson T. Vascular system defects and neuronal apoptosis in mice lacking ras GTPase-activating protein. Nature. 1995;377:695–701. doi: 10.1038/377695a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vikkula M. Vascular pathologies. Angiogenomics: towards a genetic nosology and understanding of vascular anomalies. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;15:821–822. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blinkenberg E.O., Brendehaug A., Sandvik A.K., Vatne O., Hennekam R.C., Houge G. Angioma serpiginosum with oesophageal papillomatosis is an X-linked dominant condition that maps to Xp11.3-Xq12. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;15:543–547. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houge G., Oeffner F., Grzeschik K.H. An Xp11.23 deletion containing PORCN may also cause angioma serpiginosum, a cosmetic skin disease associated with extreme skewing of X-inactivation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;16:1027–1028. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grzeschik K.H., Bornholdt D., Oeffner F., Konig A., del Carmen Boente M., Enders H., Fritz B., Hertl M., Grasshoff U., Hofling K., et al. Deficiency of PORCN, a regulator of Wnt signaling, is associated with focal dermal hypoplasia. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:833–835. doi: 10.1038/ng2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X., Reid Sutton V., Omar Peraza-Llanes J., Yu Z., Rosetta R., Kou Y.C., Eble T.N., Patel A., Thaller C., Fang P., et al. Mutations in X-linked PORCN, a putative regulator of Wnt signaling, cause focal dermal hypoplasia. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:836–838. doi: 10.1038/ng2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong J.H., Awad I.A., Kim J.H. Ultrastructural pathological features of cerebrovascular malformations: a preliminary report. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:1454–1459. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200006000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clatterbuck R.E., Eberhart C.G., Crain B.J., Rigamonti D. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical evidence that an incompetent blood-brain barrier is related to the pathophysiology of cavernous malformations. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2001;71:188–192. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labauge P., Enjolras O., Bonerandi J.J., Laberge S., Dandurand M., Joujoux J.M., Tournier-Lasserve E. An association between autosomal dominant cerebral cavernomas and a distinctive hyperkeratotic cutaneous vascular malformation in 4 families. Ann. Neurol. 1999;45:250–254. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199902)45:2<250::aid-ana17>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eerola I., Plate K.H., Spiegel R., Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Vikkula M. KRIT1 is mutated in hyperkeratotic cutaneous capillary-venous malformation associated with cerebral capillary malformation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1351–1355. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Revencu N., Vikkula M. Cerebral cavernous malformation: new molecular and clinical insights. J. Med. Genet. 2006;43:716–721. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.041079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laberge-le Couteulx S., Jung H.H., Labauge P., Houtteville J.P., Lescoat C., Cecillon M., Marechal E., Joutel A., Bach J.F., Tournier-Lasserve E. Truncating mutations in CCM1, encoding KRIT1, cause hereditary cavernous angiomas. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:189–193. doi: 10.1038/13815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahoo T., Johnson E.W., Thomas J.W., Kuehl P.M., Jones T.L., Dokken C.G., Touchman J.W., Gallione C.J., Lee-Lin S.Q., Kosofsky B., et al. Mutations in the gene encoding KRIT1, a Krev-1/rap1a binding protein, cause cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM1) Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:2325–2333. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.12.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liquori C.L., Berg M.J., Siegel A.M., Huang E., Zawistowski J.S., Stoffer T., Verlaan D., Balogun F., Hughes L., Leedom T.P., et al. Mutations in a gene encoding a novel protein containing a phosphotyrosine-binding domain cause type 2 cerebral cavernous malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:1459–1464. doi: 10.1086/380314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergametti F., Denier C., Labauge P., Arnoult M., Boetto S., Clanet M., Coubes P., Echenne B., Ibrahim R., Irthum B., et al. Mutations within the programmed cell death 10 gene cause cerebral cavernous malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;76:42–51. doi: 10.1086/426952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liquori C.L., Berg M.J., Squitieri F., Ottenbacher M., Sorlie M., Leedom T.P., Cannella M., Maglione V., Ptacek L., Johnson E.W., et al. Low frequency of PDCD10 mutations in a panel of CCM3 probands: potential for a fourth CCM locus. Hum. Mutat. 2006;27:118. doi: 10.1002/humu.9389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verlaan D.J., Laurent S.B., Rouleau G.A., Siegel A.M. No CCM2 mutations in a cohort of 31 sporadic cases. Neurology. 2004;63:1979. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000144195.55540.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verlaan D.J., Laurent S.B., Sure U., Bertalanffy H., Andermann E., Andermann F., Rouleau G.A., Siegel A.M. CCM1 mutation screen of sporadic cases with cerebral cavernous malformations. Neurology. 2004;62:1213–1215. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118299.55857.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gault J., Sain S., Hu L.J., Awad I.A. Spectrum of genotype and clinical manifestations in cerebral cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:1278–1284. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000249188.38409.03. Discussion 1284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaetzner S., Stahl S., Surucu O., Schaafhausen A., Halliger-Keller B., Bertalanffy H., Sure U., Felbor U. CCM1 gene deletion identified by MLPA in cerebral cavernous malformation. Neurosurg. Rev. 2007;30:155–159. doi: 10.1007/s10143-006-0057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felbor U., Gaetzner S., Verlaan D.J., Vijzelaar R., Rouleau G.A., Siegel A.M. Large germline deletions and duplication in isolated cerebral cavernous malformation patients. Neurogenetics. 2007;8:149–153. doi: 10.1007/s10048-006-0076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liquori C.L., Berg M.J., Squitieri F., Leedom T.P., Ptacek L., Johnson E.W., Marchuk D.A. Deletions in CCM2 are a common cause of cerebral cavernous malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:69–75. doi: 10.1086/510439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denier C., Labauge P., Bergametti F., Marchelli F., Riant F., Arnoult M., Maciazek J., Vicaut E., Brunereau L., Tournier-Lasserve E. Genotype–phenotype correlations in cerebral cavernous malformations patients. Ann. Neurol. 2006;60:550–556. doi: 10.1002/ana.20947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stahl S., Gaetzner S., Voss K., Brackertz B., Schleider E., Surucu O., Kunze E., Netzer C., Korenke C., Finckh U., et al. Novel CCM1, CCM2 and CCM3 mutations in patients with cerebral cavernous malformations: in-frame deletion in CCM2 prevents formation of a CCM1/CCM2/CCM3 protein complex. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:709–717. doi: 10.1002/humu.20712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Limaye N., Wouters V., Uebelhoer M., Tuominen M., Wirkkala R., Mulliken J.B., Eklund L., Boon L.M., Vikkula M. Somatic mutations in angiopoietin receptor gene TEK cause solitary and multiple sporadic venous malformations. Nat. Genet. 2008;41:118–124. doi: 10.1038/ng.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petit N., Blecon A., Denier C., Tournier-Lasserve E. Patterns of expression of the three cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM) genes during embryonic and postnatal brain development. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2006;6:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hogan B.M., Bussmann J., Wolburg H., Schulte-Merker S. ccm1 cell autonomously regulates endothelial cellular morphogenesis and vascular tubulogenesis in zebrafish. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:2424–2432. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zawistowski J.S., Stalheim L., Uhlik M.T., Abell A.N., Ancrile B.B., Johnson G.L., Marchuk D.A. CCM1 and CCM2 protein interactions in cell signaling: implications for cerebral cavernous malformations pathogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:2521–2531. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hilder T.L., Malone M.H., Bencharit S., Colicelli J., Haystead T.A., Johnson G.L., Wu C.C. Proteomic identification of the cerebral cavernous malformation signaling complex. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:4343–4355. doi: 10.1021/pr0704276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voss K., Stahl S., Schleider E., Ullrich S., Nickel J., Mueller T.D., Felbor U. CCM3 interacts with CCM2 indicating common pathogenesis for cerebral cavernous malformations. Neurogenetics. 2007;8:249–256. doi: 10.1007/s10048-007-0098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J., Rigamonti D., Dietz H.C., Clatterbuck R.E. Interaction between krit1 and malcavernin: implications for the pathogenesis of cerebral cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:353–359. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000249268.11074.83. Discussion 359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uhlik M.T., Abell A.N., Johnson N.L., Sun W., Cuevas B.D., Lobel-Rice K.E., Horne E.A., Dell'Acqua M.L., Johnson G.L. Rac-MEKK3-MKK3 scaffolding for p38 MAPK activation during hyperosmotic shock. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:1104–1110. doi: 10.1038/ncb1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Serebriiskii I., Estojak J., Sonoda G., Testa J.R., Golemis E.A. Association of Krev-1/rap1a with Krit1, a novel ankyrin repeat-containing protein encoded by a gene mapping to 7q21-22. Oncogene. 1997;15:1043–1049. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang J., Clatterbuck R.E., Rigamonti D., Chang D.D., Dietz H.C. Interaction between krit1 and icap1alpha infers perturbation of integrin beta1-mediated angiogenesis in the pathogenesis of cerebral cavernous malformation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2953–2960. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.25.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glading A., Han J., Stockton R.A., Ginsberg M.H. KRIT-1/CCM1 is a Rap1 effector that regulates endothelial cell cell junctions. J. Cell. Biol. 2007;179:247–254. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gault J., Shenkar R., Recksiek P., Awad I.A. Biallelic somatic and germ line CCM1 truncating mutations in a cerebral cavernous malformation lesion. Stroke. 2005;36:872–874. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000157586.20479.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akers A.L., Johnson E., Steinberg G.K., Zabramski J.M., Marchuk D.A. Biallelic somatic and germline mutations in cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM): evidence for a two-hit mechanism of CCM pathogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn430. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddn430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pagenstecher A., Stahl S., Sure U., Felbor U. A two-hit mechanism causes cerebral cavernous malformations: complete inactivation of CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 in affected endothelial cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn420. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddn420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vikkula M., Boon L.M., Carraway K.L., 3rd, Calvert J.T., Diamonti A.J., Goumnerov B., Pasyk K.A., Marchuk D.A., Warman M.L., Cantley L.C., et al. Vascular dysmorphogenesis caused by an activating mutation in the receptor tyrosine kinase TIE2. Cell. 1996;87:1181–1190. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Enjolras O., Vikkula M. Glomuvenous malformation (glomangioma) and venous malformation: distinct clinicopathologic and genetic entities. Arch. Dermatol. 2004;140:971–976. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.8.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brouillard P., Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Enjolras O., Ghassibe M., Warman M.L., Tan O.T., Olsen B.R., Vikkula M. Mutations in a novel factor, glomulin, are responsible for glomuvenous malformations (‘glomangiomas’) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:866–874. doi: 10.1086/339492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brouillard P., Ghassibe M., Penington A., Boon L.M., Dompmartin A., Temple I.K., Cordisco M., Adams D., Piette F., Harper J.I., et al. Four common glomulin mutations cause two thirds of glomuvenous malformations (‘familial glomangiomas’): evidence for a founder effect. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:e13. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Hagan A.H., Moloney F.J., Buckley C., Bingham E.A., Walsh M.Y., McKenna K.E., McGibbon D., Hughes A.E. Mutation analysis in Irish families with glomuvenous malformations. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006;154:450–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brouillard P., Enjolras O., Boon L.M., Vikkula M. Glomulin and glomuvenous malformation. In: Epstein C.J., Erickson R.P., Wynshaw-Boris A., editors. Inborn Errors of Development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 1561–1565. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boon L.M., Vikkula M. From blue jeans to blue genes. J. Craniofac. Surg. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318193d7a0. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Calvert J.T., Riney T.J., Kontos C.D., Cha E.H., Prieto V.G., Shea C.R., Berg J.N., Nevin N.C., Simpson S.A., Pasyk K.A., et al. Allelic and locus heterogeneity in inherited venous malformations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:1279–1289. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morris P.N., Dunmore B.J., Tadros A., Marchuk D.A., Darland D.C., D'Amore P.A., Brindle N.P. Functional analysis of a mutant form of the receptor tyrosine kinase Tie2 causing venous malformations. J. Mol. Med. 2005;83:58–63. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu H.T., Huang Y.H., Chang Y.A., Lee C.K., Jiang M.J., Wu L.W. Tie2-R849W mutant in venous malformations chronically activates a functional STAT1 to modulate gene expression. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2008;128:2325–2333. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Korpelainen E.I., Karkkainen M., Gunji Y., Vikkula M., Alitalo K. Endothelial receptor tyrosine kinases activate the STAT signaling pathway: mutant Tie-2 causing venous malformations signals a distinct STAT activation response. Oncogene. 1999;18:1–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kidoya H., Ueno M., Yamada Y., Mochizuki N., Nakata M., Yano T., Fujii R., Takakura N. Spatial and temporal role of the apelin/APJ system in the caliber size regulation of blood vessels during angiogenesis. EMBO J. 2008;27:522–534. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wouters V., Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Vikkula M. TEK (TIE2) and cutaneomucosal venous malformation. In: Epstein C.J., Erickson R.P., Wynshaw-Boris A., editors. Inborn Errors of Development. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 491–494. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dompmartin A., Acher A., Thibon P., Tourbach S., Hermans C., Deneys V., Pocock B., Lequerrec A., Labbe D., Barrellier M.T., et al. Association of localized intravascular coagulopathy with venous malformations. Arch. Dermatol. 2008;144:873–877. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.7.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fukuhara S., Sako K., Minami T., Noda K., Kim H.Z., Kodama T., Shibuya M., Takakura N., Koh G.Y., Mochizuki N. Differential function of Tie2 at cell-cell contacts and cell-substratum contacts regulated by angiopoietin-1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:513–526. doi: 10.1038/ncb1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saharinen P., Eklund L., Miettinen J., Wirkkala R., Anisimov A., Winderlich M., Nottebaum A., Vestweber D., Deutsch U., Koh G.Y., et al. Angiopoietins assemble distinct Tie2 signalling complexes in endothelial cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2008;10:527–537. doi: 10.1038/ncb1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saharinen P., Kerkela K., Ekman N., Marron M., Brindle N., Lee G.M., Augustin H., Koh G.Y., Alitalo K. Multiple angiopoietin recombinant proteins activate the Tie1 receptor tyrosine kinase and promote its interaction with Tie2. J. Cell. Biol. 2005;169:239–243. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yuan H.T., Venkatesha S., Chan B., Deutsch U., Mammoto T., Sukhatme V.P., Woolf A.S., Karumanchi S.A. Activation of the orphan endothelial receptor Tie1 modifies Tie2-mediated intracellular signaling and cell survival. FASEB J. 2007;21:3171–3183. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8487com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maisonpierre P.C., Suri C., Jones P.F., Bartunkova S., Wiegand S.J., Radziejewski C., Compton D., McClain J., Aldrich T.H., Papadopoulos N., et al. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science. 1997;277:55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Valenzuela D.M., Griffiths J.A., Rojas J., Aldrich T.H., Jones P.F., Zhou H., McClain J., Copeland N.G., Gilbert D.J., Jenkins N.A., et al. Angiopoietins 3 and 4: diverging gene counterparts in mice and humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:1904–1909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Loughna S., Sato T.N. Angiopoietin and Tie signaling pathways in vascular development. Matrix Biol. 2001;20:319–325. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cascone I., Napione L., Maniero F., Serini G., Bussolino F. Stable interaction between alpha5beta1 integrin and Tie2 tyrosine kinase receptor regulates endothelial cell response to Ang-1. J. Cell. Biol. 2005;170:993–1004. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim K.L., Shin I.S., Kim J.M., Choi J.H., Byun J., Jeon E.S., Suh W., Kim D.K. Interaction between Tie receptors modulates angiogenic activity of angiopoietin2 in endothelial progenitor cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;72:394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fachinger G., Deutsch U., Risau W. Functional interaction of vascular endothelial-protein-tyrosine phosphatase with the angiopoietin receptor Tie-2. Oncogene. 1999;18:5948–5953. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dominguez M.G., Hughes V.C., Pan L., Simmons M., Daly C., Anderson K., Noguera-Troise I., Murphy A.J., Valenzuela D.M., Davis S., et al. Vascular endothelial tyrosine phosphatase (VE-PTP)-null mice undergo vasculogenesis but die embryonically because of defects in angiogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3243–3248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611510104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Irrthum A., Karkkainen M.J., Devriendt K., Alitalo K., Vikkula M. Congenital hereditary lymphedema caused by a mutation that inactivates VEGFR3 tyrosine kinase. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:295–301. doi: 10.1086/303019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karkkainen M.J., Ferrell R.E., Lawrence E.C., Kimak M.A., Levinson K.L., McTigue M.A., Alitalo K., Finegold D.N. Missense mutations interfere with VEGFR-3 signalling in primary lymphoedema. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:153–159. doi: 10.1038/75997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Evans A.L., Bell R., Brice G., Comeglio P., Lipede C., Jeffery S., Mortimer P., Sarfarazi M., Child A.H. Identification of eight novel VEGFR-3 mutations in families with primary congenital lymphoedema. J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:697–703. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.9.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Joukov V., Pajusola K., Kaipainen A., Chilov D., Lahtinen I., Kukk E., Saksela O., Kalkkinen N., Alitalo K. A novel vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF-C, is a ligand for the Flt4 (VEGFR-3) and KDR (VEGFR-2) receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 1996;15:290–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Achen M.G., Jeltsch M., Kukk E., Makinen T., Vitali A., Wilks A.F., Alitalo K., Stacker S.A. Vascular endothelial growth factor D (VEGF-D) is a ligand for the tyrosine kinases VEGF receptor 2 (Flk1) and VEGF receptor 3 (Flt4) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:548–553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brice G., Child A.H., Evans A., Bell R., Mansour S., Burnand K., Sarfarazi M., Jeffery S., Mortimer P. Milroy disease and the VEGFR-3 mutation phenotype. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:98–102. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Daniel-Spiegel E., Ghalamkarpour A., Spiegel R., Weiner E., Vikkula M., Shalev E., Shalev S.A. Hydrops fetalis: an unusual prenatal presentation of hereditary congenital lymphedema. Prenat. Diagn. 2005;25:1015–1018. doi: 10.1002/pd.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ghalamkarpour A., Morlot S., Raas-Rothschild A., Utkus A., Mulliken J.B., Boon L.M., Vikkula M. Hereditary lymphedema type I associated with VEGFR3 mutation: the first de novo case and atypical presentations. Clin. Genet. 2006;70:330–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carver C., Brice G., Mansour S., Ostergaard P., Mortimer P., Jeffery S. Three children with Milroy disease and de novo mutations in VEGFR3. Clin. Genet. 2007;71:187–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ghalamkarpour A., Debauche C., Haan E., Van Regemorter N., Sznajer Y., Thomas D., Revencu N., Gillerot Y., Boon L.M., Vikkula M. (Submitted) Sporadic hydrops fetalis caused by mutations in lymphangiogenic factors VEGFR3 and FOXC2. J. Pediatr. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.02.023. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ghalamkarpour A., Holnthoner W., Saharinen P., Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Alitalo K., Vikkula M. (Submitted) Primary Congenital Lymphedema can be caused by a recessive VEGFR3 mutation. J. Med. Genet. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.064469. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Malik S., Grzeschik K.H. Congenital, low penetrance lymphedema of lower limbs maps to chromosome 6q16.2-q22.1 in an inbred Pakistani family. Hum. Genet. 2008;123:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ferrell R.E., Kimak M.A., Lawrence E.C., Finegold D.N. Candidate gene analysis in primary lymphedema. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2008;6:69–76. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2007.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Finegold D.N., Schacht V., Kimak M.A., Lawrence E.C., Foeldi E., Karlsson J.M., Baty C.J., Ferrell R.E. HGF and MET mutations in primary and secondary lymphedema. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2008;6:65–68. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2008.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fang J., Dagenais S.L., Erickson R.P., Arlt M.F., Glynn M.W., Gorski J.L., Seaver L.H., Glover T.W. Mutations in FOXC2 (MFH-1), a forkhead family transcription factor, are responsible for the hereditary lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:1382–1388. doi: 10.1086/316915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bell R., Brice G., Child A.H., Murday V.A., Mansour S., Sandy C.J., Collin J.R., Brady A.F., Callen D.F., Burnand K., et al. Analysis of lymphoedema-distichiasis families for FOXC2 mutations reveals small insertions and deletions throughout the gene. Hum. Genet. 2001;108:546–551. doi: 10.1007/s004390100528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Finegold D.N., Kimak M.A., Lawrence E.C., Levinson K.L., Cherniske E.M., Pober B.R., Dunlap J.W., Ferrell R.E. Truncating mutations in FOXC2 cause multiple lymphedema syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:1185–1189. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.11.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xue Y., Cao R., Nilsson D., Chen S., Westergren R., Hedlund E.M., Martijn C., Rondahl L., Krauli P., Walum E., et al. FOXC2 controls Ang-2 expression and modulates angiogenesis, vascular patterning, remodeling, and functions in adipose tissue. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:10167–10172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802486105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hayashi H., Sano H., Seo S., Kume T. The Foxc2 transcription factor regulates angiogenesis via induction of integrin beta3 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:23791–23800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800190200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hayashi H., Kume T. Foxc transcription factors directly regulate Dll4 and Hey2 expression by interacting with the VEGF-Notch signaling pathways in endothelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Petrova T.V., Karpanen T., Norrmen C., Mellor R., Tamakoshi T., Finegold D., Ferrell R., Kerjaschki D., Mortimer P., Yla-Herttuala S., et al. Defective valves and abnormal mural cell recruitment underlie lymphatic vascular failure in lymphedema distichiasis. Nat. Med. 2004;10:974–981. doi: 10.1038/nm1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Irrthum A., Devriendt K., Chitayat D., Matthijs G., Glade C., Steijlen P.M., Fryns J.P., Van Steensel M.A., Vikkula M. Mutations in the transcription factor gene SOX18 underlie recessive and dominant forms of hypotrichosis-lymphedema-telangiectasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:1470–1478. doi: 10.1086/375614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Francois M., Caprini A., Hosking B., Orsenigo F., Wilhelm D., Browne C., Paavonen K., Karnezis T., Shayan R., Downes M., et al. Sox18 induces development of the lymphatic vasculature in mice. Nature. 2008;456:643–647. doi: 10.1038/nature07391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ghalamkarpour A., Devriendt K., Vikkula M. SOX18 and the Hypotrichosis-Lymphedema-Telangiectasia Syndrome. In: Epstein C.J., Erickson R.P., Wynshaw-Boris A., editors. Inborn Errors of Development. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 913–915. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cermenati S., Moleri S., Cimbro S., Corti P., Del Giacco L., Amodeo R., Dejana E., Koopman P., Cotelli F., Beltrame M. Sox18 and Sox7 play redundant roles in vascular development. Blood. 2008;111:2657–2666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Herpers R., van de Kamp E., Duckers H.J., Schulte-Merker S. Redundant roles for sox7 and sox18 in arteriovenous specification in zebrafish. Circ. Res. 2008;102:12–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.166066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pendeville H., Winandy M., Manfroid I., Nivelles O., Motte P., Pasque V., Peers B., Struman I., Martial J.A., Voz M.L. Zebrafish Sox7 and Sox18 function together to control arterial-venous identity. Dev. Biol. 2008;317:405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Plummer N.W., Gallione C.J., Srinivasan S., Zawistowski J.S., Louis D.N., Marchuk D.A. Loss of p53 sensitizes mice with a mutation in Ccm1 (KRIT1) to development of cerebral vascular malformations. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;165:1509–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63409-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Plummer N.W., Squire T.L., Srinivasan S., Huang E., Zawistowski J.S., Matsunami H., Hale L.P., Marchuk D.A. Neuronal expression of the Ccm2 gene in a new mouse model of cerebral cavernous malformations. Mamm. Genome. 2006;17:119–128. doi: 10.1007/s00335-005-0098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Eklund L., Olsen B.R. Tie receptors and their angiopoietin ligands are context-dependent regulators of vascular remodeling. Exp. Cell Res. 2006;312:630–641. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Karpanen T., Alitalo K. Molecular biology and pathology of lymphangiogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008;3:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Karkkainen M.J., Saaristo A., Jussila L., Karila K.A., Lawrence E.C., Pajusola K., Bueler H., Eichmann A., Kauppinen R., Kettunen M.I., et al. A model for gene therapy of human hereditary lymphedema. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:12677–12682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221449198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pennisi D., Gardner J., Chambers D., Hosking B., Peters J., Muscat G., Abbott C., Koopman P. Mutations in Sox18 underlie cardiovascular and hair follicle defects in ragged mice. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:434–437. doi: 10.1038/74301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.James K., Hosking B., Gardner J., Muscat G.E., Koopman P. Sox18 mutations in the ragged mouse alleles ragged-like and opossum. Genesis. 2003;36:1–6. doi: 10.1002/gene.10190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bull L.N., Roche E., Song E.J., Pedersen J., Knisely A.S., van Der Hagen C.B., Eiklid K., Aagenaes O., Freimer N.B. Mapping of the locus for cholestasis–lymphedema syndrome (Aagenaes syndrome) to a 6.6-cM interval on chromosome 15q. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:994–999. doi: 10.1086/303080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.McAllister K.A., Grogg K.M., Johnson D.W., Gallione C.J., Baldwin M.A., Jackson C.E., Helmbold E.A., Markel D.S., McKinnon W.C., Murrell J., et al. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:345–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Johnson D.W., Berg J.N., Baldwin M.A., Gallione C.J., Marondel I., Yoon S.J., Stenzel T.T., Speer M., Pericak-Vance M.A., Diamond A., et al. Mutations in the activin receptor-like kinase 1 gene in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2. Nat. Genet. 1996;13:189–195. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bourdeau A., Faughnan M.E., Letarte M. Endoglin-deficient mice, a unique model to study hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2000;10:279–285. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Srinivasan S., Hanes M.A., Dickens T., Porteous M.E., Oh S.P., Hale L.P., Marchuk D.A. A mouse model for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) type 2. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:473–482. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cole S.G., Begbie M.E., Wallace G.M., Shovlin C.L. A new locus for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT3) maps to chromosome 5. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:577–582. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bayrak-Toydemir P., McDonald J., Akarsu N., Toydemir R.M., Calderon F., Tuncali T., Tang W., Miller F., Mao R. A fourth locus for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia maps to chromosome 7. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006;140:2155–2162. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Abdalla S.A., Letarte M. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: current views on genetics and mechanisms of disease. J. Med. Genet. 2006;43:97–110. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.030833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Xu X., Brodie S.G., Yang X., Im Y.H., Parks W.T., Chen L., Zhou Y.X., Weinstein M., Kim S.J., Deng C.X. Haploid loss of the tumor suppressor Smad4/Dpc4 initiates gastric polyposis and cancer in mice. Oncogene. 2000;19:1868–1874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gallione C.J., Repetto G.M., Legius E., Rustgi A.K., Schelley S.L., Tejpar S., Mitchell G., Drouin E., Westermann C.J., Marchuk D.A. A combined syndrome of juvenile polyposis and hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia associated with mutations in MADH4 (SMAD4) Lancet. 2004;363:852–859. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15732-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]