Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The epithelioid granuloma is a characteristic histological feature of Crohn’s disease. In some pathological classification schemes, the criteria for a definite, probable or possible diagnosis have been listed, with the epithelioid granuloma indicating definite Crohn’s disease.

METHODS:

In the present evaluation, 247 prospectively evaluated Crohn’s disease patients (24.3%), from a consecutively accumulated population database of 1015 patients, were found to have an epithelioid granuloma. The recently devised Montreal classification for Crohn’s disease was then applied to this granuloma-positive cohort of Crohn’s disease patients to define age at diagnosis for men and women, disease site and disease behaviour.

RESULTS:

The investigation showed that patients with Crohn’s disease and granulomas were most often diagnosed early in the course of their disease, particularly women. Their disease was often extensive, with ileocolonic and upper gastrointestinal tract involvement. Finally, disease behaviour was most often complex, especially with penetrating disease complications.

CONCLUSION:

Using homogeneous (ie, ‘reagent-grade’) patient cohorts defined by a recently devised classification method for Crohn’s disease, the study demonstrated that an epithelioid granuloma may represent a histopathological marker for an early biological event in the etiopathogenesis of Crohn’s disease, and this may have predictive significance with respect to the location and clinical behaviour of Crohn’s disease.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Disease behaviour, Disease site, Granuloma, Inflammatory bowel disease, Inflammatory process, Montreal classification

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Le granulome épithélioïde est une caractéristique histologique de la maladie de Crohn. Dans certains schèmes de classification pathologique, on établit les critères de diagnostic définitif, probable ou possible en classant le granulome épithélioïde comme indicateur définitif de maladie de Crohn.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Dans la présente évaluation, on a déterminé que 247 patients atteints d’une maladie de Crohn évalués de manière prospective (24,3 %) avaient un granulome épithélioïde au sein d’une base de données de population accumulée de 1 015 patients. On a ensuite appliqué la classification de Montréal pour la maladie de Crohn, récemment établie, à cette cohorte positive au granulome de patients atteints de la maladie de Crohn pour définir l’âge au diagnostic des hommes et des femmes, le foyer de la maladie et le comportement de la maladie.

RÉSULTATS :

L’exploration a révélé que la plupart des patients atteints de la maladie de Crohn et de granulomes, notamment les femmes, étaient diagnostiqués rapidement au cours de l’évolution de leur maladie. Leur maladie était souvent étendue, avec atteinte iléocolique et gastroduodénale. Enfin, dans la plupart des cas, le comportement de la maladie est complexe, surtout avec des complications pénétrantes de la maladie.

CONCLUSION :

Au moyen de cohortes de patients homogènes (c’est-à-dire de qualité réactif) définies d’après un récent mode de classification de la maladie de Crohn, l’étude a démontré qu’un granulome épithélioïde peut constituer un marqueur histopathologique d’événement biologique précoce dans l’étiopathogenèse de la maladie de Crohn, ce qui peut avoir une signification prédictive à l’égard du foyer et du comportement clinique de la maladie de Crohn.

The diagnosis of Crohn’s disease depends on multiple clinical, imaging and pathological criteria (1). An epithelioid granuloma, detected on microscopic examination of an endoscopic biopsy or surgically resected specimen, has been considered an especially reliable marker of Crohn’s disease. Indeed, a number of histopathological classification schemes list criteria for a definite, probable or possible diagnosis, with the presence of epithelioid granulomas indicating definite Crohn’s disease (2–5). However, in most patients with Crohn’s disease, granulomas are not detected (2–5).

Crohn’s disease is also a phenotypically heterogeneous disorder involving different geographic sites within the gastrointestinal tract. Recently, attention has focused on defining more uniform or homogeneous patient groups based on clinical characteristics such as disease location or behaviour, as well as seromarkers (eg, anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies). In recent years, using modern classification schema developed elsewhere (6), studies (7–11) have demonstrated that Crohn’s disease is female-predominant, sometimes familial, and often characterized by strictures and penetrating complications.

In the present study, 247 of the consecutively evaluated patients with detectable granulomas were evaluated using the updated Montreal classification method reported at the 2005 World Congress of Gastroenterology (12). This more modern schema includes age at diagnosis, disease location and disease behaviour for classification of Crohn’s disease, and its application was recently reported in a single-clinician Crohn’s disease cohort of over 1000 patients (13). The results of the present study have further defined these phenotypic characteristics, but in a more homogeneous Crohn’s disease population characterized by a ‘definitive’ histopathological disease marker, the epithelioid granuloma, detected in sections of endoscopic biopsies or surgically resected intestine (2–5).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Definitions and inclusions

The patients were derived from a clinical database of 1015 consecutively evaluated patients with Crohn’s disease, directly treated by the investigator over the course of more than two decades. The overall mean period of patient follow-up was more than 10 years. In an earlier report (8), this patient database was noted to be predominantly female (ie, 56.1%), with 84.4% diagnosed before 40 years of age. In addition, disease was observed to be localized in the ileum in 25.3%, the colon in 27.2%, the ileocolon in 34.6% and the upper gastrointestinal tract, despite disease involvement elsewhere, in 13.1% of cases. Finally, disease behaviour was earlier classified as stricturing (or stenosing) in 33.6% and penetrating (or perforating) in 37.2% of cases. Additional data for this Crohn’s disease population have been detailed in other recent publications (10,11).

As noted elsewhere (13), for all patients in the present evaluation, office and inpatient hospitalization records, as well as endoscopic, radiological imaging, surgical and pathology reports, were recorded. Microbiological studies were routinely performed to exclude an infectious agent that might have produced a granulomatous inflammatory tissue response (eg, Yersinia species) (14).

All pathological materials were initially reported by trained gastrointestinal pathologists and later confirmed directly by the investigator (also trained in endoscopic biopsy interpretation) after histopathological review of the pathological slides for each individual case. Endoscopic biopsies had been separately embedded in paraffin, routinely cut into four to five micron serial sections, placed on four to five glass microscopic slides for each biopsy and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. In colonic disease, isolated crypt-associated giant cells and granulomas were excluded, because these have been reported elsewhere in ulcerative colitis (15).

Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test or χ2 analysis. For the purposes of the present study, a statistically significant result was P<0.05. In addition to expression of data in percentages, the exact P values were defined, because marginally significant P values may not have accurately reflected the probability of a type I error (ie, false-positive).

Classification method

Male and female patients were each classified based on a prior published schema developed elsewhere by others (ie, Montreal classification for Crohn’s disease) (12).

Age at diagnosis:

The newly devised schema defines three different age groups as the time of diagnosis: 16 years of age or younger (A1), 17 to 40 years of age inclusive (A2) and over 40 years of age (A3).

Disease location:

The newly devised schema defines location as the maximal extent of disease or disease at the first resection (ie, L1, the ileum, possibly involving the cecum; L2, the colon; L3, the ileocolon), with upper gastrointestinal tract disease listed as a modifier for L1, L2 and L3 (ie, so as not to disregard ileal and/or colonic involvement if upper gastrointestinal tract disease is present).

Disease behaviour:

The newly devised schema defines disease behaviour as: B1, nonstricturing and nonpenetrating; B2, stricturing (or stenosing); and B3, penetrating (or perforating). Based on prior studies on the natural history of Crohn’s disease from the University of British Columbia hospital (Vancouver, British Columbia) (10), a minimum of three to five years was required in the present study to define a ‘stable’ B1 disease behavioural phenotype. In the newly devised schema, perianal fistulas and/or abscesses were also excluded from the penetrating disease behaviour category.

RESULTS

Patient population

Table 1 shows the entire Crohn’s disease patient cohort, expressed in percentages, prospectively accumulated over more than 25 years. There were 1015 patients, including 449 men (44.2%) and 566 women (55.8%), similar to earlier published data from the hospital that reflected a female-predominant population (7,13). At the time of diagnosis, 846 (83.3%) patients were 40 years of age or younger, and 169 (16.7%) were older than 40 years of age. Although the percentages of male and female patients for each of the three age groups, as defined by the Montreal classification, were similar, the predominant population was the 17- to 40-year-old group (P=0.0370 compared with the younger than 17 years age group, and P<0.0001 compared with the older than 40 years age group), with disease classified mainly in the ileocolonic region (P=0.0161 compared with the ileum only, and P<0.0001 compared with the colon only). Of these 1015 patients, 119 (11.7%) had upper gastrointestinal tract involvement and most of these (ie, over 60%) also had disease detected in the ileocolonic region. For disease behaviour, most (n=657, 64.7%) had disease that could be characterized as complex, being complicated with strictures (ie, stenosis) or penetrating (ie, perforating) complications. Similarly, complex disease behaviour (ie, with either strictures or penetrating disease complications) was predominant in each of the different age groups (younger than 17 years of age, 68.4%; 17 to 40 years of age, 65.4%; and older than 40 years of age, 59.2%), although the difference in distribution of these different disease behaviour types for each of the three age groups was only marginally significant (P=0.0477).

TABLE 1.

Crohn’s disease database (n=1015)

| All |

Age group (years) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <17 | 17 to 40 | >40 | ||

| Sex (%) | ||||

| Male | 44.2* | 45.6 | 43.4 | 46.7 |

| Female | 55.8 | 54.4 | 56.6 | 53.3 |

| Site (%) | ||||

| L1 | 26.4 | 21.9 | 27.4 | 24.9 |

| L2 | 30.8 | 21.1 | 28.1 | 49.1 |

| L3 | 42.5 | 57.0 | 44.0 | 26.0 |

| Behaviour (%) | ||||

| B1 | 35.3 | 31.6 | 34.6 | 40.8 |

| B2 | 33.7 | 33.3 | 32.6 | 37.9 |

| B3 | 31.1 | 35.1 | 32.8 | 21.3 |

Granulomas in male and female patients at different ages

Overall, 247 of 1015 patients with Crohn’s disease (24.3%) had granulomas reported either in endoscopic biopsies or surgically resected specimens. This included 105 of 449 male patients (23.4%) and 142 of 566 female patients (25.1%) for a female-predominant (ie, 57.5%) cohort. The mean durations of direct investigator follow-up for granuloma-positive male and female patients was 10.6 years and 11.3 years, respectively. Of these, most patients (179, 72.5%) were 17 to 40 years of age, not dissimilar from the overall distribution of the entire population cohort with Crohn’s disease (n=1015) (calculated P=0.6638).

Table 2 shows male and female patients in each of the different age ranges at diagnosis based on the Montreal schema for both granuloma-positive patients and patients with no granulomas detected (ie, granuloma-negative). This allowed a comparison of the granuloma-positive group with the granuloma-negative group. As expected, there were significantly more granuloma-negative male and female patients for each of the different age ranges, based on the Montreal schema (P=0.0175). However, there were no significant age-group related differences defined between the percentages of male and female patients in the granuloma-positive and granuloma-negative groups.

TABLE 2.

Age ranges at diagnosis of Crohn’s disease for granuloma-positive and granuloma-negative male and female patients*

|

Age at diagnosis (years)† |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| <17 | 17 to 40 | >40 | |

| Group total, n | |||

| Male | 52 | 318 | 79 |

| Female | 62 | 414 | 90 |

| Granuloma-positive, n | |||

| Male | 14 | 75 | 16 |

| Female | 23 | 105 | 14 |

| Granuloma-negative, n | |||

| Male | 38 | 243 | 63 |

| Female | 39 | 309 | 76 |

*Numbers for each patient group included both granuloma-positive (n=247) and granuloma-negative (n=768) patients, with granuloma-negative meaning no granuloma was detected.

†Ages, age ranges at diagnosis of Crohn’s disease based on Montreal schema

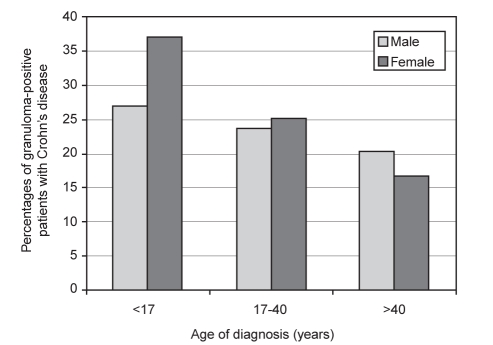

Because there were differing numbers of male and female patients in each age range at diagnosis, granuloma-positive patient groups were also expressed as a percentage of the total number of patients in each age range. Figure 1 shows the percentages for both male and female patients with granuloma-positive Crohn’s disease during their clinical course expressed in relation to each of the different age ranges at the time of diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. As shown, an increasing percentage of Crohn’s disease patients with reported granulomas were seen in the younger age groups, particularly in female patients.

Figure 1).

Percentages of males and females with Crohn’s disease that had granulomas detected during their clinical course expressed in relation to each age range at diagnosis (ie, ages younger than 17 years, 17 to 40 years and older than 40 years)

Granulomas and disease location

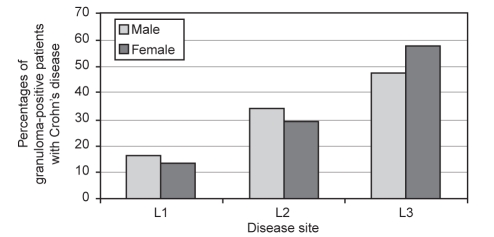

Table 3 shows male and female patients with granuloma-positive disease and granuloma-negative disease. Figure 2 schematically shows the percentages of male and female patients with granulomas for each site of disease. For both of these different modes of data expression, results were based on the Montreal classification.

TABLE 3.

Disease location* in each age group for granuloma-positive and granuloma-negative Crohn’s disease

| Disease type |

Age at diagnosis (years) |

Total, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <17 (M:F), n | 17 to 40 (M:F), n | >40 (M:F), n | ||

| Granuloma-positive | ||||

| Disease location | ||||

| L1 | 2:1 | 11:18 | 3:0 | 35 (14.3) |

| L2 | 1:7 | 23:27 | 12:7 | 77 (31.6) |

| L3 | 11:15 | 39:59 | 1:7 | 132 (54.1) |

| Granuloma-negative | ||||

| Disease location | ||||

| L1 | 12:10 | 72:100 | 16:23 | 233 (30.3) |

| L2 | 7:9 | 71:85 | 34:30 | 236 (30.7) |

| L3 | 19:20 | 100:124 | 13:23 | 299 (38.9) |

*Disease location based on Montreal classification, n=1012, with an additional three patients localized to the upper gastrointestinal tract alone (detected in granuloma-positive group, 17 to 40 years of age – two male and one female patient). F Female; L1 Ileum; L2 Colon; L3 Ileocolon; M Male

Figure 2).

Percentages of granuloma-positive male and female patients with Crohn’s disease for each disease site. L1 Ileum; L2 Colon; L3 Ileocolon

As shown, the most common location of disease for granuloma-positive disease was L3, or combined ileocolonic disease, compared with any other site for both males (51 of 105, 48.6%) and females (81 of 147, 57.0%) combined, when all age ranges were considered together (P=0.0016). This was particularly significant for male patients with ileocolonic disease (L3) compared with either localized colonic disease (L2; P<0.0001) or localized ileal disease (L1; P=0.0435). However, for the different male or female groups older than 40 years of age at diagnosis, L2 was the most common site of disease, ie, disease localized to the colon alone. This was significant for both male and female patients compared with either the L1 or L3 groups (P=0.0128) with granuloma-positive Crohn’s disease.

For both male and female patients with granuloma-positive Crohn’s disease, the percentages with disease classified as ileal (35 of 244, 14.3%]), colonic (77 of 244, 31.6%) or ileocolonic (132 of 244. 54.1%) did not achieve statistical significance compared with male and female patients with no granulomas and disease localized to the ileum (233 of 778, 29.9%), colon (236 of 778. 30.3%) or ileocolon (299 of 778, 38.4%).

Table 4 shows the numbers of granuloma-positive patients in each group with upper gastrointestinal tract disease as proposed in the new Montreal classification for Crohn’s disease in each of the different age ranges. As noted, most granuloma-positive male and female patients with Crohn’s disease involving the upper gastrointestinal tract also had concomitant involvement of the ileocolon compared with involvement of the ileum or colon alone. Moreover, a greater percentage of both male and female patients with granuloma-positive Crohn’s disease and concomitant involvement of the upper gastrointestinal tract were in the two youngest age ranges (ie, younger than 17 years of age: 12 of 37 patients (32.4%), six of 14 male patients (42.9%) and six of 23 female patients (26.1%); and 17 to 40 years of age: 32 of 180 (17.8%), 14 of 75 male patients (18.7%) and 18 of 105 female patients (17.1%). Finally, concomitant involvement of the upper gastrointestinal tract in granuloma-positive patients was rare in the older than 40 years group, with only a single male and no female patients.

TABLE 4.

Upper gastrointestinal tract involvement in granuloma-positive Crohn’s disease

| Disease site, n |

Age ranges for male patients (years) |

Age ranges for female patients (years) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <17 | 17 to 40 | >40 | <17 | 17 to 40 | >40 | |

| L1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| L2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| L3 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 0 |

| UGI only | 2 | 1 | ||||

L1 Ileum L2 Colon; L3 Ileocolon; UGI Upper gastrointestinal tract

Granulomas and disease behaviour

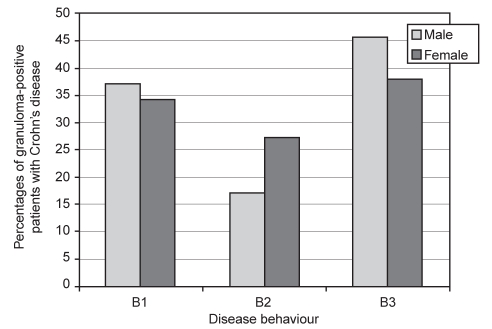

Table 5 shows different age ranges for granuloma-positive and granuloma-negative patients with the different types of disease behaviour, as specified by the Montreal classification. For each category, male and/or female patients with no granuloma detected (granuloma-negative) usually exceeded the absolute numbers of males and/or females with granuloma-positive disease (except for male patients older than 17 years of age with B3). The percentages of patients classified with different types of disease behaviour were similar for granuloma-positive and granuloma-negative patients (ie, B1, 35.6% versus 35.2%, respectively; B2, 23.1% versus 37.0%, respectively; and B3, 41.3% versus 27.9%, respectively).

TABLE 5.

Disease behaviour for granuloma-positive and granuloma-negative patients*

| Behaviour |

Age groups (years), n |

Total patients (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <17 (M:F) | 17 to 40 (M:F) | >40 (M:F) | ||

| Granuloma-positive | ||||

| B1 | 3:9 | 26:30 | 10:10 | 88 (35.6) |

| B2 | 1:5 | 13:33 | 4:1 | 57 (23.1) |

| B3 | 10:9 | 36:42 | 2:3 | 102 (41.3) |

| Granuloma-negative | ||||

| B1 | 12:12 | 92:105 | 25:24 | 270 (35.2) |

| B2 | 18:14 | 80:113 | 24:35 | 284 (37.0) |

| B3 | 8:13 | 71:91 | 14:17 | 214 (27.9) |

*Disease behaviour based on Montreal classification (n=1015) with granuloma-positive (n=247) and granuloma-negative or no granuloma detected (n=768). B1 Nonstricturing, nonpenetrating or inflammatory; B2 Stricturing or stenosing; B3 Penetrating or perforating; F Female; M Male

Figure 3 schematically shows the total number of male and female patients with granulomas for each type of disease behaviour, based on the Montreal classification. Granulomas were most commonly detected in both male (n=66, 62.9%) and female (n=93, 65.5%) patients classified with a complex form of disease behaviour, including either strictures or penetrating disease complications, compared with nonstricturing, nonpenetrating disease in male (n=39, 37.1%) and female (n=49, 34.5%) patients. Interestingly, as schematically shown in Figure 3, clinical disease behaviour characterized by penetrating complications appeared to be more common than disease behaviour characterized by stricture formation, especially in male patients.

Figure 3).

Percentages of granuloma-positive male and female patients with Crohn’s disease for each disease behaviour. B1 Nonstenosing and nonperforating or inflammatory; B2 Stenosing or stricturing; B3 Perforating or penetrating

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the clinical significance of a histopathologically detected granuloma was explored in a prospectively accumulated and consecutively evaluated Crohn’s disease population cohort of 1015 patients who were monitored by a single clinician for a mean period of over 10 years. The overall granuloma detection rate in the present study was 24.3% (ie, 247 of 1015 patients). Although it is possible that the detection rate of granulomas might have been increased with the procurement of more endoscopic biopsies, or resection of additional or extended lengths of intestine, this rate of granuloma detection closely approximates the reported rates of 25.6% from the Mayo Clinic (16) and 24.7% from a European centre (17). The inclusion of all types of tissue specimens for granuloma detection in this analysis (ie, biopsies and surgical specimens) could have introduced a form of quantitative selection bias; however, this evaluation shows that the detection, per se, of a granuloma in any type of tissue specimen may have clinical significance. Most importantly, the present report showed that phenotypic features of Crohn’s disease described elsewhere (6,12), are similarly present in a cohort that fulfills published criteria for a histopathologically definitive, rather than probable or possible, Crohn’s disease diagnosis (ie, based on the detection of epithelioid granulomas) (2–5). This so-called granuloma-positive cohort was also female-predominant with disease primarily localized in the ileocolonic region, and most often was characterized by complex behaviour with either strictures or penetrating disease complications.

The recently devised Montreal classification for Crohn’s disease (12) was used here to further define the phenotypic clinical features of this granuloma-positive cohort. A similar percentage of male and female patients with Crohn’s disease had granulomas, but based on the criterion of age at diagnosis, granulomas were more often detected if a Crohn’s disease diagnosis was made earlier in the patient’s clinical course, particularly in female patients. The detection of epithelioid granulomas at an earlier age of diagnosis of Crohn’s disease is consistent with previous reports that documented granulomas in younger adults with Crohn’s disease (18,19), and further extends this finding to a modern classification schema for Crohn’s disease using a more homogeneous (ie, ‘reagent-grade’) patient group. The observations are also consistent with the belief that the granuloma represents an adaptive mechanism for removal or localization of a possible causative agent for Crohn’s disease, which would most likely be encountered early in the clinical course of the disease (20) or, alternatively, as repeated discrete events over the long term clinical course of a disease characterized by clinical exacerbations and remissions over many decades (21). The female-predominant nature of the population studied here and the finding that granulomas are most often detected in the youngest female patients suggest that the phenotypic expression of this pathological process may be hormone-mediated. Additional studies are required to explore this intriguing new histopathological observation in Crohn’s disease.

Disease localization and disease behaviour in this granuloma-positive cohort with Crohn’s disease were also evaluated. In most of these patients, ileocolonic disease, often with disease in the upper gastrointestinal tract, was commonly associated with perforating disease behaviour. These clinical findings are consistent with the evidence in prior retrospective studies (18,22–24) that granulomas, if detected, may have prognostic significance in extensive and/or complicated Crohn’s disease (25). Additional data, derived prospectively, possibly over specifically defined time intervals, from other large population-based cohorts classified with the new Montreal schema are required to elucidate the clinical significance of granulomas, as well as other pathological changes in Crohn’s disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol (Suppl) 1989;170:2–6. doi: 10.3109/00365528909091339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heresbach D, Alexandre JL, Branger B, et al. Frequency and significance of granulomas in a cohort of incident cases of Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2005;54:215–22. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.041715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Berre N, Heresbach D, Kerbaol M, et al. Histological discrimination of idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease from other types of colitis. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:749–53. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.8.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theodossi A, Spiegelhalter DJ, Jass J, et al. Observer variation and discriminatory value of biopsy features in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1994;35:961–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.7.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahadeva U, Martin JP, Patel NK, Price AB. Granulomatous ulcerative colitis: A re-appraisal of the mucosal granuloma in the distinction of Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis. Histopathology. 2002;41:50–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, et al. A simple classification of Crohn’s disease: Report of the Working Party for the World Congress of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:8–15. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman HJ. Application of the Vienna Classification for Crohn’s disease to a single clinician database of 877 patients. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:89–93. doi: 10.1155/2001/426968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman HJ. Familial Crohn’s disease in single or multiple first-degree relatives. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:9–13. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman HJ. Natural history and clinical behavior of Crohn’s disease extending beyond two decades. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:216–9. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman HJ. Comparison of longstanding pediatric-onset and adult-onset Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:183–6. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200408000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman HJ. Age-dependent phenotypic expression of Crohn’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:774–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000177243.51967.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a working party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19(Suppl A):5–36. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman HJ. Application of the Montreal Classification for Crohn’s disease to a single clinician database of 1015 patients. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:363–6. doi: 10.1155/2007/951526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simmonds SD, Noble MA, Freeman HJ. Gastrointestinal features of culture-positive Yersinia enterocolitica infection. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:112–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90846-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahadeva U, Martin JP, Patel NK, Price AB. Granulomatous ulcerative colitis: A re-appraisal of the mucosal granuloma in the distinction of Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis. Histopathology. 2002;41:50–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramzan NN, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Shapiro MS. Clinical significance of granuloma in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:168–73. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potzi R, Walgram M, Lochs H, Holzner H, Gangl A. Diagnostic significance of endoscopic biopsy in Crohn’s disease. Endoscopy. 1989;21:60–2. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heimann TM, Miller F, Martinelli G, Szporn A, Greenstein AJ, Aufses AH. Correlation of the presence of granulomas with clinical and immunologic variables in Crohn’s disease. Arch Surg. 1988;123:46–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400250048009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierik M, De Hertogh G, Vermeire S, et al. Epithelioid granulomas, pattern recognition receptors, and phenotypes of Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2005;54:223–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.042572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambers TJ, Morson BC. The granuloma in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1979;20:269–74. doi: 10.1136/gut.20.4.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman HJ. Temporal and geographic evolution of longstanding Crohn’s disease over more than 50 years. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:696–700. doi: 10.1155/2003/719418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markowitz J, Kahn E, Daum F. Prognostic significance of epithelioid granulomas found in rectosigmoid biopsies at the initial presentation of pediatric Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;9:182–6. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198908000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anseline PF, Wlodarczyk J, Murugasu R. Presence of granulomas is associated with recurrence after surgery for Crohn’s disease: Experience of a surgical unit. Br J Surg. 1997;84:78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bataille F, Klebl F, Rummele P, et al. Histopathological parameters as predictors for the course of Crohn’s disease. Virchows Arch. 2003;443:501–7. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0863-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta N, Cohen SA, Bostrom AG, et al. Risk factors for initial surgery in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1069–77. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]