Abstract

Objectives

To assess the scale of drink spiking in our area and identify which drugs are being used to spike drinks and also to assess whether there is a problem with drink spiking in any particular establishment.

Methods

A prospective study of all patients presenting to an emergency department with alleged drink spiking over a 12‐month period. Samples were analysed for levels of alcohol and drugs of misuse. Information was collected as to where the alleged spiking took place and the involvement of the police.

Results

75 patients attended with alleged drink spiking over the period of 12 months. 42 samples were analysed and tested positive for drugs of misuse in 8 (19%) cases. 65% of those tested had alcohol concentrations >160 mg%. The alleged spiking took place in 23 different locations, with 2 locations accounting for 31% of responses. Only 14% of those questioned had informed the police.

Conclusions

Most patients allegedly having had a spiked drink test negative for drugs of misuse. The symptoms are more likely to be a result of excess alcohol.

The use of alcohol and sedating substances by rapists is a centuries‐old practice. Today, numerous legal and illegal drugs can be misused and covertly added to beverages in a social setting. Many of these substances when combined with alcohol will have their effects magnified.

There has been a lot of media coverage in recent years, mainly focusing on just a few substances, including the central nervous system depressants, flunitrazepam (rohypnol) and γ‐hydroxybutyrate (GHB). As a result, there has been a public perception that drink spiking is a widespread practice. Elliott1 reported on a series of 27 non‐fatal instances of suspected GHB intoxication in the UK between 1998 and 2003.

In a UK study of more than 1000 women who claimed drug‐assisted sexual assault, only 2% were identified as deliberate spiking cases with sedative drugs.2 The most common drug detected was alcohol in 46% of samples, with illicit drugs detected in 34%.

Wrexham County Borough comprising a mixed urban/rural population of approximately 130 000 is being actively promoted as a weekend leisure venue and attracts evening visitors from outlying areas. The emergency department receives about 61 000 new cases per annum and has no observation ward.

As with most emergency departments, alcohol‐related attendances increase dramatically at the weekend, and in common with others, we have noticed an increasing number of patients presenting, claiming that their drinks have been “spiked”. However, there are no published studies looking at this group of patients in the emergency department setting.

The aim of this study was to identify the drugs being used to spike drinks in this area and whether there seemed to be a problem in any establishment.

Methods

A prospective study was performed over a 12‐month period starting from October 2004. All patients >16 years of age who presented to the emergency department alleging that their drink had been spiked were entered into the study. The entry into the study was based purely on the patients' opinion that their drink had been spiked, not on the opinion of the health professionals looking after the patient or the presentation of the patient.

The local research ethics committee granted ethical approval.

The patient was provided with details of the study and its aims. Samples of blood (for blood alcohol level) and urine (for analysis of drugs of misuse) were obtained. These were sent for analysis with the patients' informed consent given either at the time of presentation or at the time of the follow‐up telephone questionnaire.

A follow‐up telephone questionnaire was performed a few days later. Information was collected as to where the alleged spiking took place, whether the police had been informed and their use of medication or drugs at the time in question or on a regular basis.

The samples were analysed for blood alcohol level and the presence of any of the following: cocaine, amphetamine, cannabinoid, opiates, methadone, benzodiazepines, ketamine, diphenhydramine, GHB and rohypnol.

Results

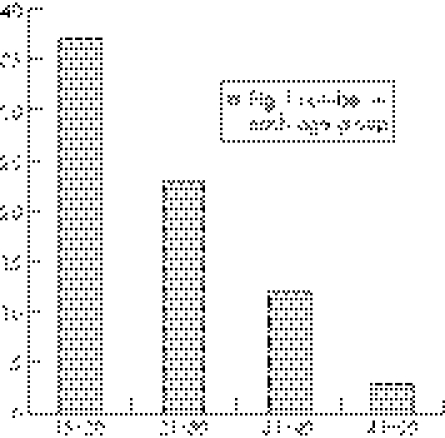

A total of 75 patients presented during the 12‐month period with 68% (n = 51) being female. Figure 1 shows the age range of the patients.

Figure 1 Number of patients in each age group.

The females outnumbered the males in every age group.

Most patients (82%) attended the department on a weekend, with 50 (66%) attending between 10 pm and 3 am.

After being seen by the doctor, 66 of the patients were discharged from the department, 6 were admitted and 3 self‐discharged before assessment. The 6 patients were admitted because of the degree of intoxication/agitation (n = 4), social reasons (n = 1) and per vaginal bleeding (n = 1).

A total of 42 urine samples were obtained and analysed (56% of study group) and tested positive for drugs of misuse in only 8 (19%) cases (box 1). No one tested positive for rohypnol or GHB.

A total of 34 blood samples were obtained and analysed for the presence of alcohol, with a limit of detection of 10 mg/dl, and tested positive in 32 (94%) cases. The results confirmed (table 1) that a large number of those tested had a high blood alcohol level. It also shows that the patients who tested positive for drugs of misuse had alcohol levels distributed across the range. All except one patient admitted to having drunk alcohol before the attendance.

Table 1 Blood alcohol concentrations of the patients .

| Alcohol concentration (mg/dl) | Number | Positive for drugs of misuse |

|---|---|---|

| No alcohol | 2 | 1 |

| <80 | 7 | 0 |

| 81–160 | 3 | 1 |

| 161–240 | 14 | 3 |

| >240 | 8 | 1 |

| Not measured | 8 | 2 |

A total of 49 (65%) patients completed the telephone questionnaire (42 had provided samples for analysis, 7 had not done so).

The alleged spiking took place in 23 different places. Only four places were mentioned on more than two occasions, with two nightclubs mentioned eight and seven times each.

The eight patients with positive results gave seven different locations at which the spiking took place.

Five patients had friends who had allegedly been spiked at the same time but had not attended the department.

Seven patients (14%) had informed the police. Three had experienced an alleged episode of spiking in the past (one had successfully prosecuted the person responsible).

Box 1 Drugs of misuse found in samples

Patient 1— amphetamine (methylenedioxymethamphetamine), cocaine

Patient 2— amphetamine (methylenedioxymethamphetamine, metamphetamine)

Patient 3— amphetamine

Patient 4— amphetamine

Patient 5— opiate (Morphine, codeine)

Patient 6— opiate (Morphine)

Patient 7— opiate (Codeine)

Patient 8— cocaine

Discussion

A recent study made by the Regional Laboratory for Toxicology at Birmingham reported an increasing number of requests received for toxicological analysis of individuals presenting to their general practitioner or hospital after self‐reported or suspected surreptitious drug administration.3 Of the 169 samples analysed between 2002 and 2004, only 73 (43%) tested positive for drugs or alcohol, with 29 testing positive for alcohol alone. Where drugs were detected, the most involved common drugs of misuse. Neither GHB nor flunitrazepam was detected in the samples analysed.

The results of our study also show that most patients presenting to the emergency department, claiming that their drink has been spiked, will test negative for drugs of misuse. Our study showed a much higher detection rate of alcohol, which is likely owing to the timing of the sample taken. The patients' symptoms may well have been the result of excess alcohol. A number of these patients probably had their drinks spiked with alcohol, but this is difficult to determine. Claiming that their drink has been spiked may also be used as an excuse by patients who have become incapacitated after the voluntary consumption of excess alcohol.

Most of the patients presented on the night of the alleged incident so even drugs with a short detection window (18 h for GHB) should still have been detected. A few patients who presented after this time period may have tested negative despite their drinks having been spiked.

The patients with positive results did not differ from those who tested negative as regards the clinical findings and symptoms. All the patients with positive results were discharged from the department, as the decision to admit was made on clinical grounds rather than on a positive test, which was returned much later.

The drugs of misuse detected in our study were opiates (codeine and morphine), amphetamines, ecstasy and cocaine. No ketamine, GHB or rohypnol was found in the samples, which suggests that they are not commonly used in this area to spike drinks. On questioning, none of the patients with positive results admitted knowingly taking drugs of misuse before presentation or being on any regular medication.

Only 14% of patients in our study had informed the police about their alleged spiked drink. In 2005, the police in northeast Wales had recorded only three cases of alleged spiked drinks (personnel communication). So it is likely that the police are unaware of the scale of the problem. The numbers in this study are likely to be an under‐representation of the true scale of the problem in the community as many may not seek medical help or may seek alternative forms of advice and support. This is evidenced by five of the patients having friends also affected at the same time but not attending the department.

The places identified as being a particular problem for suspected drink spiking are also the busiest establishments in the town centre on a weekend. The positive results did not imply any particular establishment as having a problem. This may be because of our low numbers. Departments receiving larger numbers of patients with suspected drink spiking might identify establishments in their area as having a problem. Collecting data like this could help the police target their resources on those establishments which seem to have a problem with spiked drinks.

There have been a number of publicity campaigns in recent years to raise the awareness of drink spiking. Emphasis should also be laid on how excess alcohol consumption makes people more vulnerable to assaults and injury.

In conclusion, this study confirmed our suspicion that most of the patients presenting with suspected drink spiking would test negative for drugs of misuse. We could also pass on anonymous information to the police as to the scale of the problem as we see it. We were also able to highlight possible establishments, that may have a problem with alleged drink spiking.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the emergency department in Wrexham for the collection of samples and the biochemistry departments of Wrexham and Ysbyty Gwynedd for the handling and processing of samples.

Abbreviations

GHB - γ‐hydroxybutyrate

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Ethical committee approval for this study was granted by the North East Wales Local Research Ethics Committee (application reference number 04/WnoO3/33).

References

- 1.Elliott S P. Nonfatal instances of intoxication with gamma‐hydroxybutyrate in the United Kingdom. Ther Drug Monit 200426432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott‐Ham M, Burton F C. Toxicological findings in cases of alleged drug‐facilitated sexual assault in the United Kingdom over a 3‐year period. J Clin Forensic Med 200512175–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott S P, Burgess V. Clinical urinalysis of drugs and alcohol in instances of suspected surreptitious administration (“spiked drinks”). Sci Justice 200545129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]