Abstract

Objective

To compare the effectiveness and side effects of lactated Ringer's solution (LR) and 0.9% saline (NS) in the treatment of rhabdomyolysis induced by doxylamine intoxication.

Methods

In this 15‐month‐long prospective randomised single‐blind study, after excluding 8 patients among 97 doxylamine‐intoxicated patients, 28 (31%) patients were found to have developed rhabdomyolysis and were randomly allocated to NS group (n = 15) or LR group (n = 13).

Results

After 12 h of aggressive hydration (400 ml/h), urine/serum pH was found to be significantly higher in the LR group, and serum Na+/Cl− levels to be significantly higher in the NS group. There were no significant differences in serum K+ level and in the time taken for creatine kinase normalisation. The amount of sodium bicarbonate administered and the frequency administration of diuretics was significantly higher in the NS group. Unlike the NS group, the LR group needed little supplemental sodium bicarbonate and did not develop metabolic acidosis.

Conclusion

LR is more useful than NS in the treatment of rhabdomyolysis induced by doxylamine intoxication.

Doxylamine succinate is an antihistamine commonly used as an over‐the‐counter drug to relieve insomnia, and has an anticholinergic effect. In Korea, in urban emergency departments doxylamine overdose accounts for 25% of visits due to drug overdose.1 This drug is relatively safe, but is known to induce rhabdomyolysis.

Rhabdomyolysis induced by doxylamine overdose was first reported in 1983,2 and Koppel et al3 described complications including rhabdomyolysis in 1987. It has been reported that the incidence of rhabdomyolysis induced by doxylamine overdose was 5–57%, and that rhabdomyolysis can progress to acute renal failure. Hence, early detection and treatment of rhabdomyolysis is necessary to minimise kidney damage.4,5,6

Treatment of rhabdomyolysis induced by doxylamine overdose is by aggressive hydration and urine alkalisation. Aggressive hydration with intravenous crystalloids such as 0.9% saline (NS) or lactated Ringer's solution (LR) at a rate of 300–500 ml/h in an adult is essential. To date, it has been believed that there is no difference in effectiveness between NS and LR.7,8

The development of renal failure in patients with rhabdomyolysis has been linked to renal tubular damage from the toxicity of myoglobin and haemoglobin decomposition products. At urine pH ⩽5.6, myoglobin dissociates into ferrihemate and globin. As ferrihemate has been demonstrated to be directly nephrotoxic, urine alkalisation is necessary to minimise kidney damage.9

Some investigators have reported that compared with LR, large amount of NS intravenous infusions could induce hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis, and theorised that aggressive hydration with NS might actually induce urine acidification rather than alkalisation.10,11,12

We conducted an investigation to compare the effectiveness and side effects of LR and NS as intravenous hydrating crystalloid solutions in the treatment of rhabdomyolysis induced by doxylamine intoxication.

Methods

This randomised mono‐blind study was conducted on patients who visited the emergency departments of two tertiary teaching hospitals located in Seoul, Korea, after intentional doxylamine overdose, from January 2005 to May 2006. We excluded patients who had ingested other additional drugs, or who had a history of renal, muscular, central nervous system and ischaemic heart disease from the study. The initial history and physical examination included sex, age, medical history, time from drug ingestion to hospital arrival, amount of doxylamine ingested and associated symptoms. Then general detoxification measures—for example, activated charcoal administration and gastric lavage—if indicated, were performed. The initial blood samples were sent to the laboratory for blood urea nitrogen, creatine, serum electrolyte (sodium, potassium and chloride), creatine kinase (CK), pH and myoglobin analysis. Urine was collected for pH and myoglobin analysis. The serum CK, electrolyte and urine pH were measured every 12 h thereafter.

We randomly allocated patients into the NS or LR group by picking one plastic piece from a box containing 5 pieces labelled as NS and another 5 pieces labelled as LR. This was done by a nurse who was not directly involved in patient care. After obtaining written, informed consent, patients in the LR group received lactated Ringer's solution and those in the NS group received 0.9% saline at the rate of 120 ml/h. Only the investigators, not the patients, knew which crystalloid was infused.

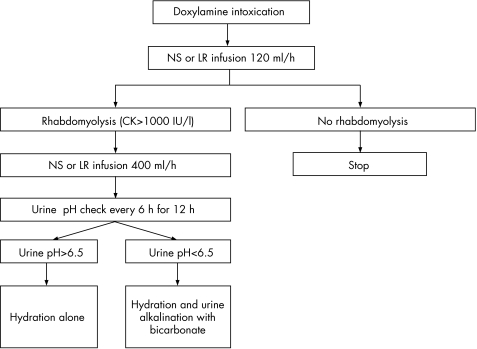

We defined rhabdomyolysis as serum CK >1000 IU/l. When rhabdomyolysis was diagnosed from the serum CK result, aggressive NS or LR infusion at the rate of 400 ml/h was started. When urine pH >6.5 was not achieved after 12 h aggressive hydration, bicarbonate was administered (fig 1). The remaining patients who did not develop rhabdomyolysis or were excluded from the study were treated with conventional method per admitting physician‘s discretion.

Figure 1 Study flowchart. CK, creatine kinase; LR, lactated Ringer's solution; NS, 0.9% saline.

During the treatment, patient blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation values were continuously monitored and chest radiography was used when pulmonary oedema was suspected. When urine output became <300 ml/h, 20% mannitol or furosemide was intravenously administered.

Data are presented as mean (SEM) or median (1Q–3Q). Data were tested for statistical significance using t test or Mann–Whitney U test, using SPSS for Windows Release 11.5. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, and was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association.

Results

Of the 97 patients admitted due to doxylamine intoxication during the study period, 8 patients were excluded due to combined overdose with other drugs. From the remaining 89 patients, rhabdomyolysis was found to have developed in 28 (31%) patients, and all consented to the study.

We randomly assigned 28 patients to LR group (n = 15) or NS group (n = 13). Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics and measurements of both groups. There were no significant differences in gender, age, amount of doxylamine ingested, initial urine pH, serum pH, and Na+ K+, Cl−, HCO3− and CK.

Table 1 Baseline parameters prior to crystalloid infusions.

| Parameter | NS* group (n = 15) | LR group (n = 13) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 7 (47) | 6 (46) | NS |

| Age (years) | 24.5 (23.5–28.5) | 26 (25–27) | NS |

| Doxylamine ingested (mg) | 2250 (750–2500) | 2000 (500–2500) | NS |

| Urine pH | 6.2 (6.0–6.5) | 6.0 (5.5–6.5) | NS |

| Serum pH | 7.46 (7.45–7.48) | 7.45 (7.43–7.47) | NS |

| Serum Na+ (mmol/l) | 142.0 (141–144) | 142 (142–144) | NS |

| Serum K+ (mmol/l) | 3.3 (3.2–3.45) | 3.4 (3.3–3.7) | NS |

| Serum Cl− (mmol/l) | 106 (104–107.5) | 107 (105–108) | NS |

| Serum HCO3− (mmol/l) | 24.4 (22.8–26.4) | 26.0 (24.7–26.8) | NS |

| Serum CK (IU/l) | 162 (45–324) | 88 (63–112) | NS |

CK, creatine kinase; LR, lactated Ringer's solution.

All values are given as median (1Q–3Q), except gender. Differences were not significant for all parameters.

*NS, 0.9% saline.

The median time to diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis was 15 h (14–17) from ingestion. When diagnosed, the median serum CK levels of NS group and LR group were 3282 (1189–7430) and 4497 (2288–9390) IU/l, respectively, without statistical difference.

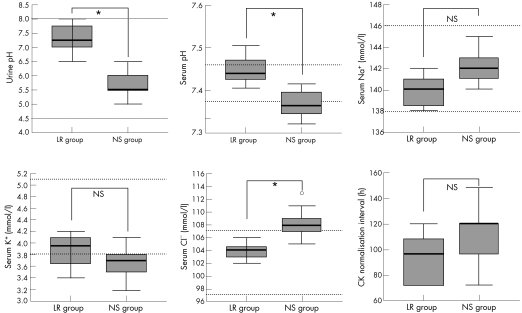

After 12 h aggressive hydration (400 ml/h), urine and serum pH of the LR group were significantly higher than those of the NS group: 7.25(7.00–7.75) vs 5.50 (5.50–6.00) and 7.44 (7.42–7.47) vs 7.36(7.34–7.39), respectively (p<0.001). As for serum electrolytes, the NS group had significantly higher serum Na+ and Cl− levels than the LR group: 142.0 (141.0–143.0) vs 140.0 (138.5–141.0) and 108 (107–109) vs 104 (103–105) mmol/l, respectively (p = 0.003). There was no difference in the serum K+ level: 3.70 (3.50–3.80) vs 3.95 (3.65–∼4.10) mmol/l, respectively (p = 0.125). The median time interval to CK normalisation (<200 IU/l) was 96 (72–108) h in the LR group and 120 (96–120) h in the NS group(p = 0.058). Figure 1 presents the data, urine and serum pH, serum concentrations of Na+, K+ and Cl−, and time interval for normalisation of CK.

For urine alkalisation, only 2 from 15 patients in the LR group received sodium bicarbonate, 40 and 60 mEq, respectively. In contrast, all 13 patients of the NS group received 140 (100–700) mEq of sodium bicarbonate for urine alkalisation (p<0.001). The median number of diuretic administrations was 1 (1–2) in the LR group and 3 (3–4) in the NS group (p = 0.001).

During treatment, no patients showed abnormal blood pressure, pulse rate and oxygen saturation. In addition, there was no abnormal findings on chest radiography.

Discussion

We compared the effectiveness of aggressive hydration of two “isotonic” crystalloids in the treatment of rhabdomyolysis induced by doxylamine intoxication and found that LR is superior to NS. We could induce urine alkalisation in most of the LR group without sodium bicarbonate, but the NS group required a large amount of sodium bicarbonate supplements. Also, massive infusion of LR did not induce metabolic acidosis in our study population.

Doxylamine succinate is an ethanolamine derivative with a half‐life of approximately 10 h. It reaches a peak plasma concentration of 0.1 μg/ml in 2–3 h after an oral administration of a standard dose of 25 mg. The majority of the drug (∼60%) is excreted unchanged in the urine, and the remainder is metabolised through various metabolic pathways.13

Although the mechanism of rhabdomyolysis is unclear, direct drug injury to the striated muscle has been suggested. Koppel et al3 reported that any muscle compression, ischaemia, trauma, prolonged seizures, infection and hypokalaemia had not been observed in all of the patients. Additionally, some reports in Korea support the evidence.4,6 In our study, we could not find causes of rhabdomyolysis other than doxylamine overdose.

In rhabdomyolysis, CK reaches a peak level within 24–36 h of muscle injury and diminishes by approximately 39% every day.14 There is no specific agreed CK level diagnostic of rhabdomyolysis. However, there is a general agreement that a CK level greater than five times the normal (>1000 IU/l) is diagnostic.15,16 In this study, we used this level as a diagnostic criteria of rhabdomyolysis.

The incidence of acute renal failure as a complication of rhabdomyolysis was various in various studies, <30% as reported by Gabow et al17 and 50% by Ron et al.18 In Korea, incidence of acute renal failure was reported as 16–58%.19,20 In our study, no patient developed acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy.

Large‐volume infusion of crystalloid has been used successfully to dilute the myoglobin load to the kidneys and maintain adequate intravascular volume in patients with rhabdomyolysis.21 This strategy reduces cast formation in the proximal tubules and “flushes” myoglobin out of the renal tubules. Although controversy exists around the optimal fluid composition and rate of administration, early, large‐volume crystalloid infusion has become the cornerstone of treatment for this group of patients. According to Ron et al,18 a large volume of crystalloid must be administered and the infusion rate is titrated to generate an hourly urine flow of approximately 200–300 ml. Better and Stein9 suggested routine alkalisation in patients with rhabdomyolysis as a means of preventing renal impairment and hyperkalaemia. In a case series of traumatic rhabdomyolysis, Ron et al18 used a protocol which administered a large amount of crystalloid and achieved a urine pH >6.5 and thus could prevent renal damage. They suggested that if it was not possible to keep the urine pH >6.5 with crystalloid and mannitol infusion alone, urine alkalisation with a large amount of sodium bicarbonate was indicated and was required. Our study protocol was similar to their protocol. When a CK level >1000 IU/l was detected, crystalloid fluid was administered at the rate of 400 ml/h. If it was not possible to keep the urine pH >6.5 with fluid administration alone, sodium bicarbonate was administered. Given the lack of strong clinical data, some authors question the necessity for sodium bicarbonate as long as the urine pH is kept >6.22 Fluid repletion and mannitol may increase the hourly urine flow to 200–300 ml, thus creating alkaline urine simply from a dilution effect. The use of sodium bicarbonate may also precipitate tetany in patients already at risk for hypocalcaemia. To investigate the effect of large amounts of LR and NS on serum/urine pH and electrolyte, sodium bicarbonate was administered when urine pH was <6.5 after 12 h of aggressive intravenous hydration.

In this study, we found that a large amount of NS infusion induced mild metabolic acidosis in contrast with mild metabolic alkalosis induced by LR infusion. There are some reports that support the occurrence of metabolic acidosis after infusions of large amounts of NS.10,11,12 Acidosis after infusion of large volumes of NS is mainly attributable to dilution of bicarbonate ions (HCO3−) through replacement of lost plasma with non‐HCO3−‐containing fluids.23,24,25 In the body, Cl− and HCO3− are usually reciprocally adjusted up or down with each other. The result of massive infusion of non‐HCO3−‐containing fluids is often a hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis. The acidosis causes impaired cardiac performance, decreased responsiveness to cardiac inotropic drugs and decreased renal perfusion.26

LR has a more physiological Cl− concentration than NS. The lactate in LR is metabolised in part in the liver by two H+‐consuming processes: gluconeogenesis (70%) and oxidation (30%).27 The consumption of H+ leaves an excess of OH−, which is free to combine with CO2 to form HCO3−. The production of HCO3− from lactate has a half‐life of 10–15 min and takes about an hour to be completed. The amount of HCO3− produced from 1 litre of LR is approximately 29 mmol. The lactate in LR does not usually increase the lactic acidaemia, if present, in patients with massive haemorrhage, unless the patients have severe liver dysfunction. The K+ level in LR is only a tiny fraction of the total body K+ level. In our study, serum K+ level was within the normal range in both groups, without significant difference.

The persistent hyperchloraemia observed after NS infusion is consistent with published reports and reflects the lower Na+/Cl− ratio in NS (1:1) than in LR (1.18:1) or plasma (1.38:1).10,11,12

Figure 2 Urine and serum pH, serum Na+, K+ and Cl− levels after 12 h hydration, and the interval to CK normalisation in the group receiving 0.9% saline (NS) and that receiving lactated Ringer (LR) solution. Data are displayed as a box and whisker plot. The bottom of the box represents the 1st quartile, and the top represents the 3rd quartile. The thick line in the box represents the median. The horizontal lines at both ends of the box represent the highest and lowest values observed. The horizontal dotted lines (……) represent the reference ranges. *p<0.05; o, outlier; NS, not significant.

Scheingraber et al11 studied the effects of randomly allocated NS or LR infusions of almost 70 ml/kg (ie, up to 5 l) over 2 h in patients undergoing elective gynaecological surgery, and found that, after 2 h of NS infusion, there was a significant decrease in pH (from 7.41 to 7.28), serum bicarbonate (from 23.5 to 18.4 mmol/l) and anion gap (from 16.2 to 11.2 mmol/l), and increase in the serum concentration of Cl− from 104 to 115 mmol/l. In the LR infusion group, there were no significant changes in pH, bicarbonate and chloride concentrations. Stewart28 described a mathematical approach to acid‐base balance in which the strong ion difference (Na++K+−Cl−) in the body is the major determinant of the H+ concentration. A decrease in the strong ion difference is associated with metabolic acidosis, and an increase with metabolic alkalosis. A change in the Cl− concentration is the major anionic contributor to the H+ homeostasis change. Hyperchloraemia caused by NS infusion, therefore, will decrease the strong ion difference and result in metabolic acidosis.11,24

Some reports have confirmed the superiority of LR for resuscitation.11,12 This may be due to the protective effect of LR against changes in chloride and pH, as critically ill patients are prone to develop an acidic state. Also, large volume (50 ml/kg over 1 h) of NS infusion in healthy volunteers has been shown to produce abdominal discomfort, pain, nausea, drowsiness and decreased mental capacity to perform complex tasks, which were not noted after LR infusions of identical volume.10

This study has some limitations. The method of randomisation is unusual and more liable to manipulation than the use of random number table. We did not measure the plasma doxylamine levels, but the comparable baseline data, including amount of doxylamine ingested, and serum CK level, will mitigate necessity of plasma level measurement.

We cannot explain the lack of difference in the time interval to CK normalisation between the NS and LR groups, despite better urine and serum pH, and serum electrolytes profiles in the LR group. Another study with more patient enrollment could clear this inconsistency. Although there are limitations, this study is the first step in finding the optimal hydration treatment for rhabdomyolysis. Subsequent studies, including the optimal volume of fluid, are expected.

Conclusions

To determine the optimal crystalloid solution, we compared NS and LR in patients with doxylamine‐induced rhabdomyolysis. There was no difference in time interval to normalisation of serum CK level after aggressive hydration treatment. But, unlike NS, patients who received LR needed little supplemental sodium bicarbonate and did not develop metabolic acidosis. Hence, LR could be used safely in the hydration therapy of doxylamine‐induced rhabdomyolysis than NS.

Abbreviations

CK - creatine kinase

LR - lactated Ringer's solution

NS - 0.9% saline

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Choi O K, Yoo J Y, Kim M S.et al Acute drug intoxication in ED of urban area. J Korean Soc Emerg Med 19952324–329. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hampel G, Horstkotte H, Rumpf K W. Myoglobinuric renal failure due to drug‐induced rhabdomyolysis. Hum Toxicol 19832197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koppel C, Tenczer J, Ibe K. Poisoning with over‐the‐counter doxylamine preparation: an evaluation of 109 cases. Hum Toxicol 19876355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon C J, Oh J H, Goo H D.et al Clinical review of doxylamine succinate overdose. J Korean Soc Emerg Med 19989317–322. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frankel D, Dolgin J, Murray B M. Non traumatic rhabdomyolysis complicating antihistamine overdose. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 199331493–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park J S, Yun Y S, Chung S W.et al Incidence and prediction of rhabdomyolysis following doxylamine overdose. J Korean Soc Emerg Med 200011120–126. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tintinalli J E, Kelen G D, Stapczynski J S. eds. Emergency medicine. A comprehensive study guide. 6th edn. New York: McGraw‐Hill, 20041751

- 8.Richards J R. Rhabdomyolysis and drugs of abuse. J Emerg Med 20001951–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Better O S, Stein J H. Early management of shock and prophylaxis of acute renal failure in traumatic rhabdomyolysis. N Engl J Med 1990322825–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams E L, Hildebrand K L, McCormick S A.et al The effect of intravenous lactated Ringer's solution versus 0.9% sodium chloride solution on serum osmolarity in human volunteers. Anesth Analg 199988999–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheingraber S, Rehm M, Sehmisch C.et al Rapid saline infusion produces hyperchloremic acidosis in patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. Anesthesiology 1999901265–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho A M, Karmakar M K, Contardi L H.et al Excessive use of normal saline in managing traumatized patients in shock: a preventable contributor to acidosis. J Trauma 200151173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthew J E, Seth S, Gray O.et alEllenhorn's medical toxicology: diagnosis and treatment of human toxicology 2nd edn. William and Wilkins, Baltimore 1997888–889.

- 14.Tan W, Herzlich B C, Funaro R.et al Rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuric acute renal failure associated with classic heat stroke. South Med J 1995881065–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welch R D, Todd K, Krause G S. Incidence of cocaine‐associated rhabdomyolysis. Ann Emerg Med 199120154–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brody S L, Wrenn K D, Wilber M M.et al Predicting the severity of cocaine‐associated rhabdomyolysis. Ann Emerg Med 1990191137–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabow P A, Kaehny W D, Kelleher S P. The spectrum of rhabdomyolysis. Medicine 198261141–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ron D, Taitelman U, Michaelson M.et al Prevention of acute renal failure in traumatic rhabdomyolysis. Arch Intern Med 1984144277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H Y, Choi S O, Shin S J.et al Analysis of 250 cases of rhabdomyolysis. Korean J Nephrol 199413810–817. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin Y T, Bin K T, Sim S S.et al Clinical features of rhabdomyolysis induced acute renal failure. Korean J Nephrol 199413818–825. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slater M S, Mullin R J. Rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuric renal failure in trauma and surgical patients: a review. J Am Coll Surg 1998186693–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honda N. Acute renal failure and rhabdomyolysis. Kidney Int 198323888–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters J H, Miller L R, Clack S.et al Cause of metabolic acidosis in prolonged surgery. Crit Care Med 1999272142–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prough D S, Bidani A. Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is a predictable consequence of intraoperative infusion of 0.9% saline. Anesthesiology 1999901247–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorje P, Adhikary G, Tempe D K. Avoiding iatrogenic hyperchloremic acidosis: call for a new crystalloid fluid. Anesthesiology 200092625–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narins R G, Bastl C P, Rudnick M R. Acid‐base metabolism. In: Goncik HC, ed. Current nephrology. New York: Wiley, 198279–130.

- 27.White S A, Goldhill D R. Is Hartmann's the solution? Anaesthesia 199752422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart P A. Modern quantitative acid‐base chemistry. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1983611444–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]