Abstract

A case of initial resuscitation of a patient with severe burns is described. Such patients can have hypotension and reduced organ perfusion for a number of reasons, and can remain in the emergency department for many hours while awaiting transfer to specialist centres. The case provides a comparison between resuscitation using traditional burns formulae and a relatively new and simple‐to‐use cardiac output (CO) monitor—the Vigileo monitor (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, California, USA). The case demonstrates that relying on fluid regimes alone can lead to insufficient resuscitation. We suggest that using technologies such as those mentioned in this article, which have the potential to be used in the emergency department, could improve the initial resuscitation of patients with burns.

A 67‐year‐old woman had 23% combination partial/full thickness flame burns on her face, anterior chest and arms. Her weight was 55 kg.

She presented promptly to the nearest emergency department (ED) and was given fluid resuscitation in line with the Parkland formula (see table in appendix A). This was continued for the first 4 h post burn. After this, on the advice of the plastic surgery registrar, the fluid regime was changed to follow the Muir and Barclay formula. This regime was continued until arrival in the intensive care department.

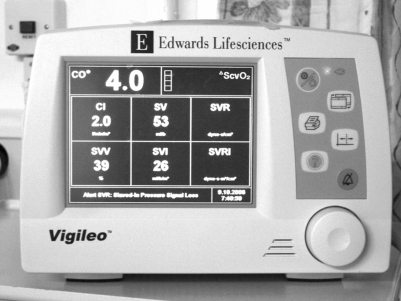

As no beds were available in the burns centre closest to the patient, she was transferred 50 miles to the nearest available centre. Upon arrival in the intensive therapy unit, 8 h had elapsed since the time of injury, and the patients' blood pressure (BP) was noted to be 80/50 mm Hg. The Vigileo monitor (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, California, USA) (fig 1) was used to provide additional data, and hence to assist in deriving the cause of the hypotension.

Figure 1 Vigileo monitor.

The patients' low BP could have been due to myocardial depression, manifested by a low CO and cardiac index (see table in appendix B). Alternative causes were hypovolaemia, suggested by a high stroke volume variation (SVV), or peripheral vasodilatation indicated by a low systemic vascular resistance (SVR). Using data from the monitor, it was possible to support the circulation with the appropriate treatment—inotropes, fluid or vasopressors.

Initially, the patients' cardiac output, cardiac index and SVR were within normal limits, but her SVV was 20% (normal<10%, see table in appendix B). This correlated with her low central venous pressure of <2 mm Hg. She was therefore resuscitated with intravenous colloid (4.5% human albumin solution) as per the Muir and Barclay formula. Additional boluses were given to maintain a systolic BP of >100 and a urine output of >30 ml/h. In total, 6.5 l of extra fluids were required in addition to those predicted by the formula during the initial resuscitation, which took place in the intensive therapy unit (table 1 shows actual fluid requirements, compared to those predicted by the formulae mentioned above).

Table 1 Actual fluid requirements.

| Time after burn (h) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regime | 0–8 | 8–24 | 24–36 | Total (ml)* |

| Parkland | 2530 | 2530 | 632.5 | 5692.5 |

| Muir and Barclay | 1265 | 1897.5 | 632.5 | 3795 |

| Actual given | 1990 | 5440 | 3510 | 10850 |

*Not including maintenance.

Eventually, the patient's SVV was normalised. However, her SVR fell to <800, indicating she had become vasodilated. At this point, a small dose of norepinephrine was used to maintain the systolic BP. It is important to use such agents judiciously in patients with burns as they cause vasoconstriction and hence reduce skin blood flow. Inotropic agents were not required in the initial 36 h period. Using this regime, we were able to maintain a mean systolic BP of 112.4 mm Hg and a mean urine output of 62.4 ml/h from admission to 36 h post burn.

Discussion

The patient with severe burns is among the most complex ones encountered in the critical care environment. Due to the specialist treatment required for patients with burns, they often spend many hours in the ED awaiting transfer to dedicated centres. An article published in this journal showed an average time of 10 h to reach a burns centre.1 In this period, good resuscitation is vital as poor skin perfusion can lead to progression of burn depth.

A number of formulae have been developed to guide the initial fluid resuscitation in patients with burns. Examples include the Parkland, and the Muir and Barclay formulae. Several studies have demonstrated that such formulae underestimate fluid requirements post burn.2 In this case, considerable volumes of additional fluid were required. An alternative strategy proposed3 is the use of continuous monitoring and physiological parameters to guide treatment. Cardiac output monitors can provide such information, and help determine the aetiology of hypotension and consequent reduced organ perfusion that occurs in patients with burns. The Vigileo monitor calculates stroke volume from the arterial pressure signal; CO is obtained by multiplying the calculated stroke volume by the heart rate. Until recently, cardiac monitors required thermal or chemical dilution to calculate cardiac output. Although accurate, they required regular calibration and the insertion of specific catheter devices. Another alternative is the use of doppler ultrasound probes, placed either in the suprasternal notch4 or in the oesophagus. These are non‐invasive, but can be technically difficult to use for inexperienced staff. The main advantages of the Vigileo monitor are that it requires no manual calibration, and its specialist sensor attaches to an existing arterial line, which means that no additional vascular access is required. These innovations mean that the monitor can be set up and used with less training, and opens up the use of such equipment in environments outside of a critical care setting, such as the ED.

We feel that CO monitors are helpful in the management of patients with severe burns as they allow continuous adjustment of fluid administration, and indicate the need for the use of other agents to support the circulation. Previous cardiac monitors were too complex for use outside a critical care environment; however, technologies such as those demonstrated in this article are simple enough to be potentially used in the ED. We feel that the early use of such equipment could improve the resuscitation of patients with severe burns, and assist in providing better outcomes in this patient group.

Appendix A

Resuscitation formulae.

| (a) Parkland | |

| Day 1 | 4 ml×weight (kg)×% burn (crystalloid), ½ in 1st 8 h, ½ in next 16 h (and maintenance fluids) |

| Day 2 | 0.5 ml/kg/% burn in first 12 h (colloid)+crystalloid to maintain urine output |

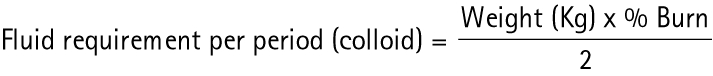

| (b) Muir and Barclay | |

|

|

| Period 1 | 4 h (1–4) |

| Period 2 | 4 h (5–8) |

| Period 3 | 4 h (9–12) |

| Period 4 | 6 h (13–18) |

| Period 5 | 6 h (19–24) |

| Period 6 | 12 h (25–36) |

Appendix B

Cardiovascular parameters.

| Stroke volume (SV) | Amount of blood ejected per beat (40–120 ml) |

| Cardiac output (CO) | Amount of blood leaving the heart in 1 min, equal to heart rate × SV (5–8 l/min) |

| Cardiac index (CI) | CO per body surface area (2.5–4.2 l/min/m2) |

| Mean arterial pressure (MAP) | Diastolic BP+⅓ (systolic–diastolic) (70–110 mm Hg) |

| Central venous pressure (CVP) | Pressure in large veins entering the right heart (0–10 cmH2O) |

Abbreviations

BP - blood pressure

CO - cardiac output

ED - emergency department

SVR - systemic vascular resistance

SVV - stroke volume variation

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Informed consent was obtained for publication of the person's details in this report.

References

- 1.Ashworth H L, Cubison T C, Gilbert P M.et al Treatment before transfer: the patient with burns. Emerg Med J 200118349–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cartotto R C, Innes M, Musgrave M A.et al How well does the Parkland formula estimate actual fluid resuscitation volumes? J Burn Care Rehabil 200223258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holm C, Mayr M, Tegeler J.et al A clinical randomised study on the effects of invasive monitoring on burn shock resuscitation. Burns 200430798–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanson J M, Van Hoeyweghen R, Kirkman E.et al Use of stroke distance in the early detection of simulated blood loss. J Trauma 199844128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]