Abstract

Longitudinal studies of substance users report difficulty in locating and completing 12-month interviews, which may compromise study validity.

OBJECTIVE

This study examined rates and predictors of contact difficulty and in-person follow-up completion among patients presenting with cocaine-related chest pain to an inner-city ED. We hypothesize less staff effort in contacting patients and lower follow-up rates would bias subsequent substance use analysis by missing those with heavier substance misuse.

METHODS

219 patients 19-60 yrs (65% males; 78% African-American) with cocaine related chest pain were interviewed in the ED, and then in person at 3, 6, and 12-months. Demographics, substance use measures, and amount/type of research staff contacts (telephone, letters, home visits, and locating patient during return ED visits) were recorded. Linear regression analyses were conducted to predict quantity of patient contacts for the 12-month follow-up.

RESULTS

Interview completion rates at 3, 6 and 12-months were: 78%, 82%, and 80%. Average contact attempts to obtain each interview were: 10 at 3-months (range 3-44), 8 at 6-months (1-31), and 8 at 12-months (1-50); 13% of patients required a home visit to complete the 12 month interview. Participants requiring more contact attempts by staff reported frequent binge drinking at baseline (p<.01) and were more likely to report prior mental health treatment (p<.05). Findings demonstrate that substantial staff effort is required to achieve adequate retention over 12- months of patients with substance misuse. Without these extensive efforts participants with a history of binge drinking would be missed at follow-up biasing longitudinal analyses.

Keywords: Cocaine, Alcohol, Emergency Department, Research Methodology, Attrition, Longitudinal

INTRODUCTION

A primary challenge facing researchers conducting longitudinal studies with Emergency Department (ED) patients is the difficulty encountered in locating patients for follow-up assessments.1, 2 While many patient populations are difficult to track longitudinally, patients with unstable employment, housing, and medical care present challenges frequently encountered by ED researchers. This is particularly true when conducting investigations with substance abuse populations, as the chaotic and sometimes transient lifestyle of these individuals can impede the researchers’ ability to maintain contact over an extended period of time.3 Although statistical approaches to compensate for random attrition are available,4-6 and have been described elsewhere for ED populations2 the most desirable approach is to reduce attrition by implementing effective patient tracking and retention techniques.7, 8

Follow-up rates from ED studies of patients with substance misuse vary greatly by study with attrition rates ranging from less than 10% to more than 50%.7-13 Low follow-up rates threaten study validity. The need to identify effective tracking methods arises from the knowledge that incomplete data can compromise the internal and external validity of a study, limiting the generalizability of study findings because those who were not assessed may have differed on the independent and dependent variables thereby affecting the results and subsequent conclusions.14, 15 Because some attrition is inevitable in longitudinal follow-up studies, understanding individual and contextual characteristics that predict contact difficulty (defined as either the amount of time or the number of attempts required to locate a participant and complete a follow-up assessment) has tremendous utility for planning longitudinal studies. Further, examination of contact difficulty provides insight into the problem with final analysis the possible bias that attrition might cause in the interpretation of study findings.

This study adds to the ED literature by examining rates and predictors of contact difficulty and in-person follow-up completion among adult patients presenting with recent cocaine use to an inner-city ED. Although the population described is one of substance users, the concepts of longitudinal tracking of typically hard to reach ED patients in the inner city may have a broader utility. This paper will examine whether less staff availability or effort in contacting patients and subsequent lower follow-up rates would bias findings by missing those with greater substance use during the 12-month follow-up. In addition, this paper will describe the contact efforts used by this project, so that recommendations can be provided to assist other investigators in planning longitudinal studies in the ED with transient or hard to reach populations.

METHODS

Study Design

This natural history study screened a consecutive cohort of patients presenting to an ED with recent cocaine use and chief complaint of chest pain to participate in a longitudinal study. All research procedures were approved by the investigators’ institutional review boards. This study was conducted at a Level 1 inner-city ED (see Booth 2005, Cunningham 200716; 17 for a more detailed research protocol description). This ED is located in a socio-economically depressed region with high levels of poverty (ranking in the bottom 15 of 331 Metropolitan areas in the U.S. in unemployment rate18 Standard of care at study hospital requires chest pain patients, age 60 and under, undergo urine screening for cocaine metabolites with their acute coronary syndrome workup.

Sample Recruitment

Research staff recruited patients in the ED between the hours of 8 a.m. and 10 p.m., seven days per week, during the two and one-half year recruitment period. Consecutive patients age 18-60 were approached by research staff to participate in the screening. For the screening, research staff obtained written informed consent to view patient medical records to determine study eligibility for which participants could choose a $1 gift. Eligibility for Phase 2 include: ages of 18-60; positive toxicological urine screen for cocaine or, if urine screen results were incomplete or unavailable, physician documentation of cocaine use. Patients were ineligible based on if they were: pregnant, unable to provide informed consent (e.g., unconscious, incarcerated), or acutely suicidal/ homicidal (requiring physical restraint or security monitoring during the ED visit). After signing a written consent form, participants in Phase 2 completed a two-hour baseline interview during their visit (see Measures) and received a $25 gift card (e.g., Wal-Mart, Target).

Follow-up Procedures

Information gathered at baseline and during contact efforts was used for retaining and tracking participants in the research study over the 12-month follow up period.

Tracking Information Gathered

At baseline, participants were asked to provide information that would allow study personnel to contact them for follow-up interviews to be conducted at 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month post-baseline. All procedures were IRB approved. Specific information collected included: date of birth, social security number, telephone numbers (work, cellular and home), and living and mailing address. Study personnel also gathered the names, telephone numbers, and addresses of at least two contact persons (e.g., spouse, family, and friend) who would know their whereabouts over the next year. Participants also were asked to provide names of other individuals, including case workers, physicians, and social service agency workers, as well as location of places where they often hang out (e.g., churches, shelters). Prior to discharge, participants were given an index card containing the project logo (CPR), baseline interviewers name, project telephone number and toll free number that they could use to contact study personnel, as well as the interview dates and payment information for each follow up interview. A review of the participant’s medical record, which includes identifying information, assisted in confirming information provided by the participant.

During subsequent contacts with a participant, locator information was verified or updated. For hard to reach (HTR) participants, hospital medical records were searched in addition to public databases such as Department of Public Health death records, internet people finder databases (e.g. Alumnifinder, Yahoo People Search), and offender/prison websites.

Contact Efforts

Participants were called within two weeks after their baseline assessment and contact information was confirmed and participants were reminded of the 3-month follow-up date. Approximately four weeks before each scheduled follow-up date, a letter was sent to participants informing them of their upcoming interview and interview payment. “Forwarding address correction requested” was stamped on the envelope so that the post-office would notify the project if a letter had been forwarded to a new address. Cases were assigned to interviewers two weeks prior to scheduled due dates. Interviewers were expected to locate and interview participants within two weeks following the scheduled interview date. Once assigned a case, interviewers would call the participant’s contact numbers, typically between 8am and 10pm, 7 days per week, until they scheduled the interview, without harassing participants. Typically interviewers would call throughout the day, but leave no more than one message per day. If an interviewer was not sure if a person lived at an address, a letter was sent certified mail, return receipt requested. In compliance with IRB requirements, if at any time participant asked not to be contacted, they were thanked for their participation and no further efforts made. When possible, scheduled participants were sent a reminder letter and called the night before the interview. If a participant failed to show at the appointed time, they were called again and if needed sent a missed appointment letter.

For participants who did not have a scheduled interview one week prior to their due date, a second letter was sent and the assigned interview started to contact the designated participant’s contacts. A home visit was scheduled on occasions when an interview was not scheduled by the due date. Home visits would also occur for participants who didn’t respond to the initial letter and had no known phone number. A letter informing the participant of the home visit was sent out one week prior to the scheduled visit. These home visits would occur in pairs (for safety) and took place during daylight hours. If the participant was not home, interviewers left friendly, handwritten notes on index cards similar to the ones given to the participant at baseline. During visits to the participant’s residence, study personnel would attempt to contact neighbors to confirm if the participant resided at that address or if they knew their current address. During winter months, letters (without revealing that study was related to substance use) were left at local shelters where participants had been previously known to stay.

Follow -Up Interview Protocols and Staff Motivation

At all times, confidentiality was assured with mail, messages on machines, and conversations with significant others. All project related stationery and business cards used a generic project name that was not related to substance use (CPR for Chest Pain Risk). During the consent process participants were ensured of the confidentiality of their responses and information and consented to follow-up interviews. When leaving messages the project name was used, but no mention of substance use or inclusion criteria was made or would be revealed. When so instructed by the participant, study personnel would not contact a person (e.g., spouse) even if previously allowed to do so.

A research assistant who lived in the local community where a majority of the subjects resided tracked the participants and conducted follow-up interviews. Participants were asked to come to the study office located at the participating medical center where the baseline interview occurred; most participants were comfortable returning to a known environment. If needed, transportation by taxi was provided paid for by the project. Some participants preferred to meet at a convenient public location such as a fast-food restaurant. Finally, when these efforts were exhausted, participants were interviewed in their homes with staff following a detailed safety procedure including traveling in pairs. At the medical center or restaurant, interviewers paid for refreshments (e.g., coffee, soda).

Remuneration methods used to enhance compliance with follow-up interviews included remuneration for time spent of $30 gift card for the 3-month interview, $35 gift card for the six-month interview and a $45 gift card for the 12-month interview. During follow-up, participants were also asked to provide a voluntary urine specimen, for which they were provided an extra remuneration of $10 gift card. As stated previously, participants were also provided with a toll-free 1-800 phone number to contact study offices and were given an incentive of $5 per interview if they telephoned the study office within two weeks of their scheduled interview date, or agreed to have their follow-up interview take place at the Medical Center.

One problem frequently encountered by follow-up staff was decreasing motivation and increasing frustration over months of attempting to contact hard-to-reach participants. Several procedures were used to provide a team atmosphere that reduced interviewer burn-out. First, interviewers were paid hourly for interviews and travel time, and were reimbursed for mileage. Interviewers helped each other trouble-shoot difficult cases and brainstorm case-finding alternative strategies at one hour weekly meetings. During these meetings all active cases were discussed and interviewers were praised for their efforts especially for the completion of interviews. Although interviewers were discouraged from trading cases, they frequently assisted each other in the location efforts.

Measures

The validity of self-report was enhanced via the use of trained interviewers that assured confidentiality and privacy during interviews for research interviews19; in addition, urine drug screens were obtained which increases the validity of self-report19-21.

The Substance Abuse Outcomes Module

(SAOM);22 is designed for evaluation of substance abuse treatment outcomes (www.netoutcomes.net), and measures DSM-IV substance use disorders,23 and outcome domains. For the current study, the SAOM was used to measure basic demographic information including age, gender, race, marital status, education, and employment status as well as information on lifetime and recent (past 3-month) substance use diagnoses, substance abuse and mental health treatment history.24 The SAOM has undergone extensive reliability and validity examinations and demonstrates reasonable reliability (internal reliability, coefficient α 0.58-0.90, test-retest reliability 0.56-0.99) and validity (concurrent validity generally 0.5-0.8, predictive validity 0.5-0.9).25 Concurrent validity for the SAOM was based on longer key instruments such as a structured diagnostic interview for substance use disorders, the CIDI-SAM,26 and the Addiction Severity Index (ASI).27 The SAOM has shown a 90-93% agreement with the CIDI-SAM on DSM-IV substance use diagnosis (present/absent).25 Self-reported use of substance abuse treatment services included lifetime and past-year use of formal specialty treatment services and/or informal services (e.g., self-help groups), as well as past-year report of any mental health-related treatment or treatment for depression.

Tracking Measures

Correspondence and tracking efforts were recorded in Contact logs, and listed as one of five categories: (1) Interviewer Telephone Calls- telephone calls made by any research staff member, including to a participant, a participant contact, and other locations (e.g., shelters, work). These calls often were made in the evening up to 10 p.m. (follow up staff often worked 3-11 for this reason); (2) Participant Initiated Calls- telephone calls received by staff members, including calls from the participant and participant contacts; (3) Letters- letters sent by research staff, including initial contact letters, hard to reach letters, home visit letters, letters to shelters and missed appointment letters; (4) Return Emergency Department visits- any return visits to the emergency department of the medical center identified by interviewers where contact was made with participants; (5) Home Visits - Home visits made by research staff (in pairs for safety).

Data Analysis

Descriptive information regarding interview completion rates, number of contact attempts, and types of contact attempts were computed. Logistic regression analyses were used to identify potential differences between study completers versus non-completers. For analysis the number of each of the 5 types of contact efforts were summed into a total count. Finally, linear regression analyses were conducted to predict number of 12-month contacts required based upon baseline characteristics. For this model, demographics (i.e., age, gender, race, marital status, hourly wage) were entered on the first step. Problem severity indicators such as days of cocaine and binge drinking in prior 4 weeks, substance abuse and/or dependence diagnoses, and lifetime substance use treatment and mental health treatment were entered on step 2.

RESULTS

Among the 302 individuals presenting to the ED during the recruitment period with recent cocaine use and chest pain, 73% agreed to participate (n=219), 19% refused to participate, and 8% were missed by recruitment staff (e.g., occupied with other subjects, patient discharged prior to RA evaluation). The average age for the 219 participants was 38.5 years with 64% of the sample being male and 78% African-American (Table 2). All participants (via eligibility criteria) had recent cocaine use and 48% meet criteria for cocaine dependence. Sixty percent of the sample graduated from high school and 75% reported income of less then $20,000 per year.

Table 2.

Demographic, Substance Use, and Psychosocial Characteristics N=219.

| Characteristics | n or Mean (SD) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Male | N=140 | 64 % |

| Age (mean, SD) | 38.5 (8.92) | ---- |

| African-American | N=169 | 77 % |

| Married / living together- | N=49 | 22 % |

| High school educated (yes) | N=132 | 60 % |

| Currently Employed | N=90 | 41 % |

| Annual income | ||

| <$10,000 | N=61 | 35 % |

| $10,000 - 19,999 | N=65 | 37 % |

| >= $20,000 | N=50 | 28 % |

| Substance Use | ||

| Substance Use Diagnoses past 12-month | ||

| Any abuse/dependence diagnosis | N=142 | 65 % |

| Cocaine abuse/dependence | N=106 | 48 % |

| Other Drug abuse/dependence | N=13 | 6 % |

| Substance use frequency (past 4 weeks) | ||

| Days binge drinking | 6.0 (9.46) | ---- |

| Days using marijuana | 7.1 (9.86) | ---- |

| Days using crack/cocaine | 7.5 (8.50) | ---- |

| Psychosocial | ||

| Social Support score | 73.06 (20.85) | --- |

| Psychological Distress | 71.9 (26.43) | ---- |

| Depression Symptom Severity | 10.5 (7.92) | ---- |

| Lifetime Mental Health Treatment | --- | 38% |

Interview Completion Rates and Description

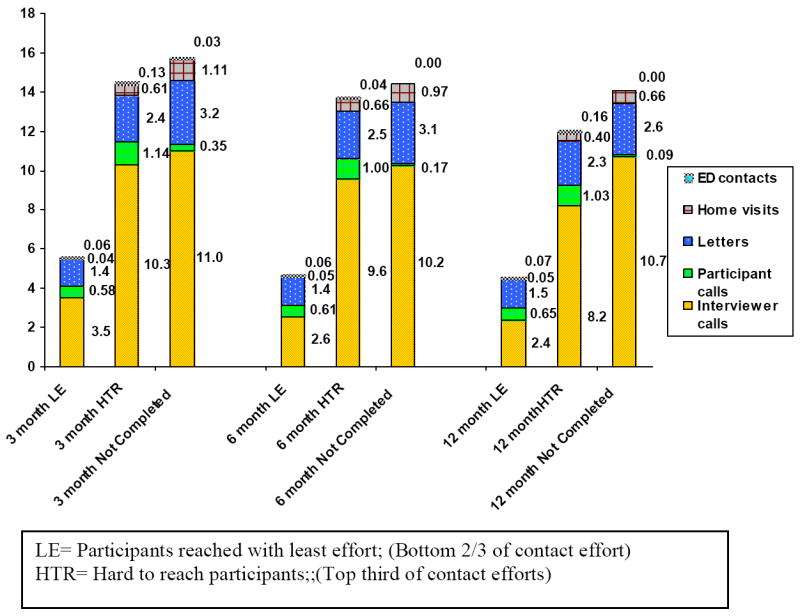

Interview completion rates were: 77%, 82%, and 80% at 3, 6, and 12-months respectively (See table 1). Study protocol included urine drug screens at all follow-up interviews and over 90% of participants completed Urine Drug Screen (91%, 91%, and 94% at each follow up interview respectively). Contact attempts varied by type and effort including telephone, letters, in-person ED return visits, and in person home visits; with 12% of the 3 month follow up interviews requiring a home visit for completion. Figure 1 describes the number of contact attempts per participant by type of contact. Contact efforts were summed to create a total count of contacts. Participants who staff reached with the least effort (two thirds of all participants were reached with between 4 and 6 contacts total) were deemed “Least Effort” (LE). In contrast hard to reach (HTR) participants required approximately three times the interviewer calls and two times the number of home visits to successfully complete follow-up interviews (Figure 1). For those participants that did not complete a 3-month interview (n=45), 53% (n=24) did go on to complete a 6-month or 12-month interview. However, in comparison, of those that did complete a 3-month interview (n=170), 96% went on to complete a 6-month or 12-month interview, demonstrating the importance of retaining participants at the initial follow-up data point.

Table 1.

Follow Up Interview Completion Rates

| Time of Follow up | Completed Interview (%) | Home Visits (%) | Average contact attempts at each interview (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 month | 77 | 12 | 10 (3-44) |

| 6 month | 82 | 6 | 8 (1-41) |

| 12 month | 80 | 8 | 8 (1-50) |

Figure 1.

Average number of contacts per participant by contact type for follow up interviews

Comparisons of Study Drop-outs with Participants Completing 12-Month Follow-up

Logistic regression analyses compared those who completed the 12-month follow-up (n=172) with non-completers (n=38) on baseline factors (i.e., gender, age, hourly wage, married (yes/no), race (African-American/other), lifetime substance use treatment (yes/no), mental health treatment (yes/no), substance abuse dependence (yes/no), binge drinking, and cocaine use days) was significant (X2 (21) = 33.4, p<.001). Further examination of individual variable contribution showed that only two variables were significant: women (Wald statistic = 7.8; p<.01) and those with greater hourly wages (Wald statistic = 12.1; p<.01) were less likely to complete the 12-month interview.

Predicting Contact Difficulty at 12-month Follow-up

Linear regression analyses were conducted to predict contact difficulty at the 12-month interview based on baseline characteristics on the sample who completed an interview (n=159). Demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, marital status, hourly wage) entered on step 1 significantly predicted contact difficulty (R2 = 0.081; F(5,153) = 2.69; p<.05); participants requiring more contact attempts were younger (ß=-0.23; p<.01). Problem severity indicators (i.e., days of cocaine and binge drinking days in prior 4 weeks, substance abuse/dependence diagnoses, lifetime substance use treatment, mental health treatment) entered on step 2 significantly improved the model (R2 change= 0.074; F Change (5,148) = 2.61;: p<.05); participants requiring more contact attempts reported more days of binge drinking (ß=0.23; p<.01) and were less likely to report prior mental health treatment (ß=-0.17: p<.05).

DISCUSSION

Substantial effort is needed to re-interview patients with substance use who are enrolled in inner-city ED based studies. A review of the medical literature found a paucity of information regarding the efforts needed to retain study participants from non-mental health medical settings. Understanding the factors and resources needed to retain patients in longitudinal research from the ED may aid in the successful planning and execution of ED based research projects. Although the extent of contact efforts needed to complete follow-up interviews in this study varied considerably, they tended to be greater at the 3-month follow-up than at either the 6- or 12-month follow-ups. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have also found attrition rates to be highest at the first follow-up28, 29. Without the resources to make these extensive contact attempts, patients reporting more binge drinking at time of study enrollment would have been missed at follow-up biasing longitudinal analyses.

ED participants requiring more contact attempts over the year were younger, engaged in more episodes binge drinking, and reported less mental health treatment than did participants who required fewer contact attempts. Those patients who are younger may be less established or settled in the community. In addition it may be that those with no mental health treatment in the past are less comfortable completing subsequent questionnaires on sensitive topics such as depression and substance use. Patients that were less likely to complete follow-ups despite significant attempts were more likely to be women or have and greater hourly wage then those who did stay in the study. For these patients the financial incentive offered may not have been a sufficient motivator. In this underserved population where women are likely to be head of household it may be that competing demands make study participation, even with a financial incentive, more difficult. Our finding that patients requiring more contact attempts were significantly more likely to have engaged in binge drinking is in line with several previous studies in patients undergoing outpatient substance use treatment,29, 30 but has not been demonstrated in patients in ED based studies. Prior ED based evaluation by Woolard et al2 found that demographic characteristics (including gender and socioeconomic status) did not predict dropouts, or those who were difficult to contact. Neuner et al,13 (2007) in an ED study evaluating contact difficulty among primarily Caucasian patients in Germany with alcohol misuse, found that individuals with greater alcohol problems required more contact attempts to complete follow-up interviews. Figure one demonstrates the considerable staff resources and associated budgetary allotment that are used to follow both the hard to reach patients as well as the 20 % that were never located for follow up.

Following patients who were enrolled in the ED has different challenges than tracking patients enrolled in an outpatient clinic or substance abuse treatment setting where they have repeat scheduled visits and have an established relationship with a provider or therapist. These challenges can be exacerbated in the inner city ED where financial, insurance and educational barriers to continuity of outpatient care often exceed those in more affluent settings. In addition, following patients with substance misuse or abuse has additional challenges. For instance, Scott31 (2004) notes that understanding the norms of the substance abuse population (e.g., frequent changes in living environment, transitory nature of relationship with many collateral contacts) is a necessary component in reducing contact difficulty. Contact difficulty is affected by the extent of location information gathered at baseline, financial constraints that limit the amount of time spent locating participants, failure to ensure participants’ confidentiality and establish rapport, assessments occurring at inconvenient times or locations, or lack of adequate reimbursements.2, 31, 32

Longitudinal follow up of any population of ED patients presents challenges that are best identified early and planned for, most specifically in the grant planning stages by including an adequate follow up budget. The authors have found that estimating five hours of research staff time, per follow up, per subject provides a rough estimate to ensure that there is adequate budget to complete the follow up phase of a study protocol with urban ED patients. Although this initially may seem excessive when viewed in light of the budget portion allotted to intervention development and recruitment the benefit justifies the cost especially when considering the difficulty of analyzing data with poor follow up rates. In addition, our experience shows that the personal characteristics of research staff that are successful at tracking patients for follow up interviews tend to differ from those who are the most successful at recruiting patients in the ED setting. Successful follow up staff are often local residents, know the community well, are willing to go to participant’s houses and shelters, and view each patient follow up in a manner similar to detective work. These skills and attributes often differ from the recruiting staff that may or may not be from the immediate area, are very comfortable in a medical setting with ill patients and medical staff, and who need to be able to comfortably approach ED patients and succeed at obtaining consent for study enrollment. Due to these differing skills, in general the follow up staff is hired separately from the recruiting staff and, while maintaining a spirit of teamwork with occasional overlap as practical logistics demand, their tasks are separated from that of recruiters.

Although it remains controversial how much attrition is acceptable without biasing study; current standards in other settings suggest at least 70%. Several recent studies have challenged this view, citing concerns that a 30% attrition rate has the potential to engender bias effects that are as large as the treatment effects under review (e.g., Foster, Hedeker, Scott33, 34). Scott (Scott, 2004 #1636 ranked participants in two substance use studies according to the number of contacts required to complete an interview. When comparing the first 70% of participants (who therefore needed fewer contacts for completion) and the remaining 30% that required the most contacts, data suggested that including only 70% led to biases that were severe enough to compromise the internal validity of the studies. This may suggest that follow up rates closer to 80% then 70 % are required to maintain study validity.

One limitation of this study is that all data is based on self-report. However, the use of standardized measures, assurance of confidentiality (including a NIDA certificate of confidentiality), inclusion of urine drug screens, use of research staff, and lack of consequences for reports has been shown to increase the validity of data regarding both substance use and involvement with illegal activities.19, 35 Finally, data from this study is from an inner- city ED and may not generalize to other more affluent or suburban populations of substance users.

Conclusions

These findings make a novel and important contribution to the ED literature by examining rates and predictors of contact difficulty and in-person follow-up completion among substance users in an inner-city ED. The contact efforts used successfully by this project in a population that is typically hard to follow may assist investigators in planning other longitudinal ED studies with substance users as well as other hard to reach populations in urban settings. Findings demonstrate that substantial staff effort is required to successfully follow patients with over 12-months. However, without these extensive efforts those who reported heavier binge drinking would be missed at follow-up biasing longitudinal analyses. Although statistical approaches are available to correct biases2, it is always preferable to prevent attrition through implementation of tracking efforts. These findings have implications for future ED based longitudinal research.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, RO1 grant #DA14343. The Authors wish to acknowledge Harvey Siegel for his contributions to the project, Pat Bergeron for her assistance with manuscript preparation, and Hurley Medical Center.

References

- 1.Longabaugh R, Woolard RE, Nirenberg TD, Minugh AP, Becker B, Clifford PR, Carty K, et al. Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(6):806–816. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolard RH, Carty K, Wirtz P, Longabaugh R, Nirenberg TD, Minugh PA, Becker B, et al. Research fundamentals: follow-up of subjects in clinical trials: addressing subject attrition. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(8):859–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown SS. Drawing Women into Prenatal Care. Family Planning Perspective. 1989;21(2):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McArdle JJ, Hamagami F. Modeling incomplete longitudinal and cross-sectional data using latent growth structural models. Exp Aging Res. 1992;18(34):145–166. doi: 10.1080/03610739208253917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazumdar S, Liu KS, Houck PR, Reynolds CF., 3rd Intent-to-treat analysis for longitudinal clinical trials: coping with the challenge of missing values. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33(2):87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu MC, Albert PS, Wu BU. Adjusting for drop-out in clinical trials with repeated measures: design and analysis issues. Stat Med. 2001;20(1):93–108. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20010115)20:1<93::aid-sim655>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribsil K, Walton MA, Mowbray CT, Luke DA, Davidson WI, Boots-Miller BJ. Minimizing participant attrition in panel studies through the use of effective retention and tracking strategies: Review and recommendations. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1996;19:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Twitchell GR, Hertzog CA, Klein JL, Schuckit MA. The anatomy of a follow-up. Br J Addict. 1992;87(9):1327–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Levenson S. Project ASSERT: an ED-based intervention to increase access to primary care, preventive services, and the substance abuse treatment system. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30(2):181–189. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capaldi D, Patterson GR. An approach to the problem of recruitment and retention rates for longitudinal research. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:169–187. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mello MJ, Nirenberg TD, Longabaugh R, Woolard R, Minugh A, Becker B, Baird J, et al. Emergency department brief motivational interventions for alcohol with motor vehicle crash patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(6):620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumann T, Neuner B, Weiss-Gerlach E, Tonnesen H, Gentilello LM, Wernecke KD, Schmidt K, et al. The Effect of Computerized Tailored Brief Advice on At-risk Drinking in Subcritically Injured Trauma Patients. J Trauma. 2006;61(4):805–814. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196399.29893.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neuner B, Fleming M, Born R, Weiss-Gerlach E, Neumann T, Rettig J, Lau A, et al. Predictors of loss to follow-up in young patients with minor trauma after screening and written intervention for alcohol in an urban emergency department. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(1):133–140. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Claus RE, Kindleberger LR, Dugan MC. Predictors of attrition in a longitudinal study of substance abusers. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34(1):69–74. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marmor JK, Oliveria SA, Donahue RP, Garrahie EJ, White MJ, Moore LL, Ellison RC. Factors encouraging cohort maintenance in a longitudinal study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44(6):531–535. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90216-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Booth BM, Weber JE, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Massey L, Thrush CR, Maio RF. Characteristics of cocaine users presenting to an emergency department chest pain observation unit. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(4):329–337. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Tripathi SP, Weber J, MaIo RF, Booth BM. Past Year Violence Typologies Among Patients with Cocaine Related Chest Pain. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. doi: 10.1080/00952990701407512. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michigan Department of Community Health. Census 2000. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Self-report issues in alcohol abuse: State of the art and future directions. Behavioral Assessment. 1990;12:91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babor TF, Kranzler HR, Lauerman RJ. Early detection of harmful alcohol consumption: comparison of clinical, laboratory, and self-report screening procedures. Addict Behav. 1989;14(2):139–157. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hser YI, Maglione M, Boyle K. Validity of self-report of drug use among STD patients, ER patients, and arrestees. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25(1):81–91. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith GR, Burnam MA, Mosley CL, Hollenberg JA, Mancino M, Grimes W. Reliability and validity of the substance abuse outcomes module. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1452–1460. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DSM-IV Draft Criteria. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1993. American Psyciatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longbaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInc): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. 1995 Volume. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith GR, Burnam MA, Mosley CL, Hollenberg JA, Mancino M, Grimes W. Measuring substance abuse treatment and outcomes: The reliability and validity of the Substance Abuse Outcomes Module. Little Rock, AR: 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cottler LB, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The reliability of the CIDI-SAM: a comprehensive substance abuse interview. Br J Addict. 1989;84(7):801–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen WB, Tobler NS, Graham JW. Attrition in Substance Abuse Prevention Research: A Meta-Analysis of 85 Longitudinally Followed Cohorts. Eval Rev. 1990;14(6):677–685. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walton MA, Ramanathan CS, Reischl TM. Tracking substance abusers in longitudinal research: understanding follow-up contact difficulty. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26(2):233–253. doi: 10.1023/a:1022128519196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nemes S, Wish E, Wraight B, Messina N. Correlates of treatment follow-up difficulty. Subst Use Misuse. 2002;37(1):19–45. doi: 10.1081/ja-120001495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott CK. A replicable model for achieving over 90% follow-up rates in longitudinal studies of substance abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74(1):21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Digiusto E, Panjari M, Gibson A, Rea F. Follow-up difficulty: correlates and relationship with outcome in heroin dependence treatment in the NEPOD study. Addict Behav. 2006;31(7):1201–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster EM, Bickman L. An evaluator’s guide to detecting attrition problems. Eval Rev. 1996;20(6):695–723. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD, Waternaux C. Sample Size Estimation for Longitudinal Designs with Attrition: Comparing Time-Related Contrasts between Two Groups. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1999;24(1):70–93. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51(3):253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00028-3. discussion 267-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]