Abstract

Conclusions

The wide phylogenetic distribution of Oxa1-related proteins appears to reflect both the central role of assembling energy-transducing membrane complexes, and the range of roles in their assembly that Oxa1-related protein scan be adapted to. In different species, Oxa1 and its isoforms appear to assist in the assembly of several different substrate proteins. Recent work on the bacterial protein YidC strongly indicates that it is capable of functioning alone as a translocase for hydrophilic domains and an insertase for TM domains. Thus it is highly likely that the eukaryotic members of this family found in mitochondria and chloroplasts directly catalyze these reactions in a co- and/or posttranslational way. It is presently unclear how Oxa1 recognizes its substrates and whether additional factors assist in this, beyond its direct interaction with mitochondrial ribosomes, demonstrated in S. cerevisiae. Given the apparent co-translational nature of in vivo Oxa1 dependent translocation of the Cox2 N-terminal domain, a detailed mechanistic study of this most criticalOxa1 function will need to await the development of a true in vitro translation system derived from the mitochondrial matrix and inner membrane. However, Oxa1is also capable of assisting post-translational insertion and translocation in isolated mitochondria and Cox18 may post-translationally translocate both in vivo and in vitro its only known substrate, the Cox2 C-terminal domain. Thus, biochemical analysis of some of these functions in proteoliposomes may already be possible, taking advantage of the wide variety of mutant forms of S. cerevisiae Oxa1, to examine distinct activities of the protein. It is clear that interpretation of all genetic and biochemical data on Oxa1 and Cox18 will be far more robust when the structure of both proteins in the membrane will be determined.

Keywords: membrane insertion, membrane translocation, cytochrome c oxidase, ATP synthase, mitochondrial ribosom, Cox18, YidC

Introduction

The evolution of mitochondria as integrated eukaryotic cellular organelles required both the development of protein import machineries for the uptake of proteins synthesized in the cytoplasm, as well as machineries for the insertion of proteins into the inner mitochondrial membrane from the matrix compartment [1, 2]. The first mitochondria presumably had the membrane insertion and translocase systems of their alpha-proteobacterial ancestors for the insertion of membrane proteins from the inside. Indeed, at least some extant unicellular eukaryotes retain remnants of the bacterial SecYEG translocase system [3]. However, in the well studied mitochondria of fungi, animals, and plants, there is no evidence for the presence of descendants of these bacterial translocase functions [4].

Polytopic inner membrane proteins related to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein Oxa1, the first such protein discovered, represent one conserved function that facilitates insertion of mitochondrial inner membrane proteins from the inner, matrix, side. Members of this ancient family of proteins have been shown to have critical roles in membrane insertion and assembly of energy transducing complexes in eukaryotic organelles (mitochondria and chloroplast) and bacterial systems, although their precise mechanisms remain to be elucidated. In this review, we attempt to integrate experimental findings and information from comparative studies bearing on the functions and physiological roles of Oxa1-related proteins in mitochondrial biogenesis. Previous valuable reviews focussing on these proteins from a variety of perspectives include [5–12].

1) Amino acid sequence and evolutionary conservation of Oxa1-related proteins

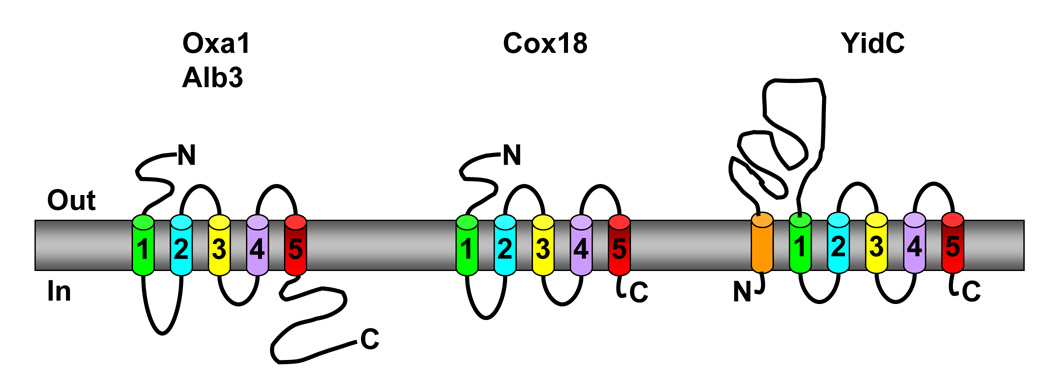

The signature feature of mitochondrial Oxa1-related proteins is a group of five transmembrane (TM) domains that are likely to carry out its central function(s) in membrane protein insertion (Figure 1) [2, 11, 13–16]. Spacing of the downstream four TM domains is highly conserved [17]. As expected for proteins with multiple hydrophobic segments, those Oxa1-related proteins that have been experimentally studied appear embedded within the inner-membrane of mitochondria by sub-fractionation and alkali treatment of mitochondria and have their C-termini located on the internal, cis, side of the membrane [13, 16–21]. Oxa1 and Cox18 have an Nout-Cin orientation verified through protease protection experiments [13, 16, 17]. The hydrophilic domains of Oxa1 adhere to the positive inside rule [22] where the soluble N-terminus and loop between TM2 and TM3 bear net negative charges while the C-terminus and matrix localized loops bear net positive charges [13]. The conservation between species of this charge distribution, despite low sequence similarity, suggests its importance in topogenesis.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the general architectures of Oxa1-related proteins. The relative spacing of helices number 2–4 is largely conserved. A large internal C-terminal domain is present in mitochondrial Oxa1 and chloroplast Alb3, but absent in mitochondrial Cox18 and bacterial YidC. E. coli YidC has an N-terminal ‘anchor’ TM domain and long periplasmic N-terminal loop not found in the organellar proteins or related proteins from Gram positive bacteria. See text for references.

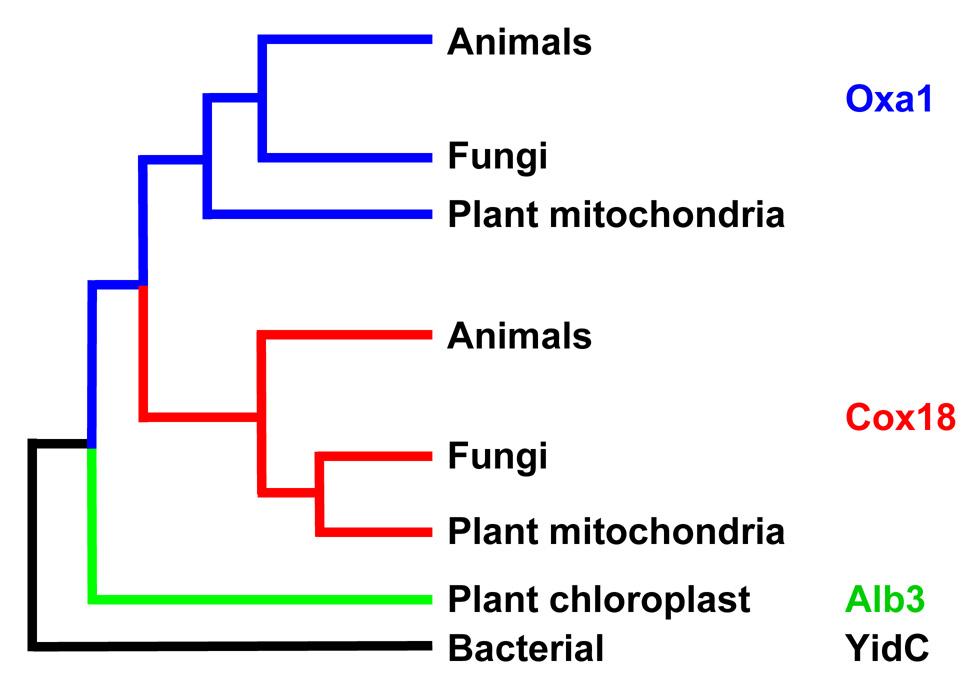

Mitochondrial inner membranes typically contain proteins from two distinct Oxa1 subfamilies (Figure 2). Those proteins most closely related to S. cerevisiae Oxa1 have long (roughly 100 residues) hydrophilic tails at their C-terminal ends. Those most closely related to Cox18 of S. cerevisiae (termed Oxa2 in Neurospora crassa) lack long hydrophilic C-terminal domains [17]. While the amino acid sequence conservation between the Oxa1 and Cox18 subfamilies is weak, their homology is clear from both their TM core structure and functional complementation studies (described below). Divergence of the Cox18 subfamily of mitochondrial proteins from those closely resembling S. cerevisiae Oxa1 appears to have occurred prior to the divergence of animals, plants and fungi [17]. The Oxa1-related thylakoid membrane chloroplast protein, Alb3, appears to have an independent origin, presumably from Cyanobacteria [17].

Figure 2.

Evolutionary relationships among eukaryotic Oxa1-related proteins. This figure is adapted from the analysis of [17] to illustrate the apparent early divergence of Oxa1 and Cox18 subfamilies in the eukaryotic lineage. It is important to note that similarities among closely related proteins within subfamilies are more complex than shown here: the Oxa1 and Cox18 proteins of Schizosaccharomyces pombe are more closely similar to those of most animals than other fungi, while the Oxa1 and Cox18 proteins of Caenorhabditis elegans are more closely similar to those of most fungi than other animals [17]. Chloroplast Alb3 and the mitochondrial proteins presumably entered eukaryotic lineages separately from different bacterial ancestors.

The bacterial members of this family are known as YidC proteins, of which the Escherichia coli example is by far the best studied [21, 23, 24]. E. coli YidC, like those of other gram negative bacteria, has five TM domains corresponding to those of Oxa1, and an additional anchor TM domain near the N-terminus: the protein has a large periplasmic loop between its first two TM domains, and N-in, C-in topology [15, 25, 26]. The large periplasmic domain linking the N-terminal anchor to the first TM domain of the conserved core domain has been crystallized [27–30]. This domain forms a twisted β-sandwich with an α-helical linker which orients the sandwich near the core TM domains. A portion of this periplasmic domain mediates an interaction with SecF [31], although this is not essential for inner membrane biogenesis or cell viability [25]. Oxa1-like proteins of Gram positive bacteria (which lack an outer membrane) lack the additional anchor TM domain and large extra-cellular domain [21, 32].

The presence of Oxa1-related proteins in several species of Archaea is strongly suggested by genome sequencing [6, 11, 12]. However, these proteins appear to lack two of the TM domains (numbered 3 and 4 in Figure 1) found in the mitochondrial and bacterial proteins. The function of these proteins in Archaea has not been experimentally studied. Nevertheless, it appears that Oxa1-related proteins may have evolved before divergence of the three major domains of life [6, 11, 12].

To date, eukaryotic Oxa1-related proteins have been found in energy transducing organelles that contain their own genetic systems, but no where else in the cell. Interestingly, genes for these proteins cannot be identified in the genome sequences of Giardia lamblia or Trichonomas vaginalis. These unicellular eukaryotic parasites contain double-membranous organelles related to mitochondria, but lack respiratory complexes and organelle genetic systems [33]. Thus, it is plausible to speculate that Oxa1-related proteins were lost in these lineages since they were no longer needed to insert organelle-encoded proteins into the inner membrane.

2) Regulation, synthesis and import of Oxa1 and Cox18 in various organisms

Both Oxa1 and Cox18 are nuclear-encoded, synthesized on cytoplasmic ribosomes and imported into mitochondria. Interestingly, S. cerevisiae OXA1 belongs to a divergent transcription unit also controlling the expression of the PET122 gene, coding a translational activator of the mitochondrial COX3 mRNA [34]. The expression of the two nuclear genes OXA1 and COX18 clearly differs. The OXA1 mRNA is abundant while the COX18 mRNA is difficult to detect, both in yeasts and human [20, 35]. Estimates of protein abundance based on accumulation of GFP fusion proteins are 6550 and 468 molecules per cell for Oxa1 and Cox18, respectively [36]. The synthetic respiratory haplo-insufficiency of COX18/cox18 heterozygotes producing a Cox2 fusion protein inside mitochondria [16] probably reflects the low level of COX18 expression.

Northern blot analysis has shown that the human gene for Oxa1, OXA1L, exhibits tissue specific expression [35]. However, the expression of yeast OXA1 is not altered by either the carbon source or by respiratory deficiency [37, 38]. In Schizosaccharomyces pombe the two COX18 mRNAs are differentially expressed depending on the carbon source [35].

The 3’-UTRs of OXA1 and COX18 mRNAs of S. cerevisiae contain binding sites for Puf3, an RNA binding protein located at the cytosolic face of the mitochondrial outer membrane that regulates mitochondrial biogenesis [39, 40]. The two mRNAs are clearly enriched in mitochondrion-bound polysomes suggesting that in vivo their import could be co-translational [41, 42]. In vitro import experiments with isolated S. cerevisiae mitochondria and radiolabeled precursors indicate that the import of these two proteins requires the TOM/TIM import machinery, the membrane potential, the import motor mtHsp70, and matrix ATP [2]. This process converts the precursors to mature forms after cleavage of a long presequence,42 aa in the case of S. cerevisiae Oxa1, by the mitochondrial processing peptidase [13, 17, 19, 43, 44]. Interestingly, after mature Oxa1 and Cox18 become located in the matrix following import into mitochondria isolated from an Δoxa1 strain or a thermosensitive mutant(oxa1-ts1402), they cannot be inserted normally into the inner-membrane [17, 45]. This lack of insertion could be due either to a direct role for Oxa1 in its own insertion (and that of Cox18p), or to the diminished membrane potential of the mutant mitochondria. In any event, a Δoxa1 mutant strain can be restored to respiratory proficiency by the introduction of aplasmid carrying the OXA1 gene, showing that at least some Oxa1 can be inserted into an inner-membrane previously devoid of Oxa1.

Oxa1 appears to form a homotetrameric complex as judged by blue-native PAGE and superose size exclusion chromatography [44, 46, 47]. Similarly, Cox18 migrates as a high molecular complex of unknown composition, but distinct from the Oxa1 complex [17]. Mutant forms of Oxa1 are highly sensitive to degradation by m-AAA proteases and the metallopeptidase Oma1 in S. cerevisiae [48].

3) Consequences of Oxa1 deficiency in various organisms

The OXA1 gene was first isolated from S. cerevisiae by functional complementation of a respiratory deficient nonsense mutant in the W106 codon (oxa1-79, Kermorgant & Dujardin unpublished, [37]) and a L240S missense mutation in the loop between TM2 andTM3 (Figure 3) (oxa1-ts1402, [49]). The oxa1-79 strain lacked spectrally detectable cytochrome aa3 and showed reduced splicing of both the COX1 and CYTb precursor transcripts. Removal of all mitochondrial introns did not cure the respiratory deficiency, indicating that the splicing deficiency is a secondary phenotype [37]. Since all mitochondrially-encoded proteins could be radio-labeled in the mutant, albeit with reduced efficiently for Cox1, Cox2 and Atp6 [50], the defect leading to respiratory deficiency appeared to be post-translational [37, 49]. Furthermore, processing of the N-terminal leader peptide ofthe Cox2 precursor was defective in oxa1 mutant strains [37, 49]. As discussed below, failure to process pre-Cox2 is caused by failure to translocate the N-terminal domain of this mitochondrially synthesized protein to the IMS.

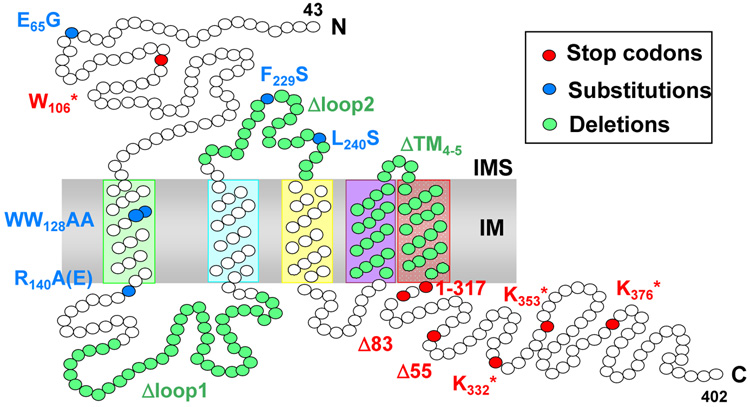

Figure 3.

Mutations affecting S. cerevisiae Oxa1. Phenotypes caused by these mutations are summarized in table 1.

Consistent with the spectral deficiency and lack of pre-Cox2 processing, cytochrome c oxidase activity was abolished in Δoxa1 cells and complex IV assembly was defective as judged by Blue-Native Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) experiments. In addition, complex V was barely detectable in BN-PAGE and ATP synthase activity was strongly decreased [51, 52]. In contrast, complex III was reduced to a lesser extent [51]. Consistent with these assembly defects, the steady-state levels of several subunits of respiratory complexes IV and V were dramatically reduced [19, 50, 52] (Table 1). However, Atp9 was reduced to a lesser extent than the other F0 subunits [50, 52], probably due to assembly of the Atp9 oligomer into an F1-Atp9 subcomplex that stabilizes it [53].

Table 1.

Effects of Oxa1 or Cox18 absence or depletion in several organisms

| Lack or depletion of Oxa1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory complexesa | |||||||

| I | II | III | IV | V | Effects on subunits | References | |

| S. cerevisiae | na | nd | ≈ 0 |

: Cox4 Cox6 F1-α F1-β F1-γ F1-δ OSCP F0-c (Atp1, 2, 3, 16, 5, 9) : Cox4 Cox6 F1-α F1-β F1-γ F1-δ OSCP F0-c (Atp1, 2, 3, 16, 5, 9) |

[19, 37, 49, 50, 52] | ||

: Cytb FeS Cox3 Cox5 F0-a F0-b F0-f (Atp6, 4, 17) : Cytb FeS Cox3 Cox5 F0-a F0-b F0-f (Atp6, 4, 17)≈ 0: Cox1 Cox2 Cox6a solubility  : Cox4, Cox6 : Cox4, Cox6trypsin sensitive: Cox2, Cox4 unprocessed: Cox2 |

|||||||

| S. pombeb | na | nd | [38] | ||||

| N. crassac | nd | nd | nd |

: NDUFS3 NDUFV2 (30 & 24 kDa) : NDUFS3 NDUFV2 (30 & 24 kDa) : Cox2 Cox3 : Cox2 Cox3 |

[46] | ||

| P. anserinad | + | nd | + | [54] | |||

| H. sapiense | + | + |

: Cox1 Cox2 : Cox1 Cox2 : NDUFA9 NDUFB6 : NDUFA9 NDUFB6 : F1-α F1-β OSCP F0-d : F1-α F1-β OSCP F0-d |

[47] | |||

| Lack of Cox18: | |||||||

| Respiratory complexesa | |||||||

| I | II | III | IV | V | Effects on subunits | References | |

| K. lactis | na | nd | + | ≈ 0 | nd | [102] | |

| S. cerevisiae | na | nd | ≈ + | ≈ 0 | + |

≈ 0: Cox2 synthesis: Cox1 synthesis: Cox1 |

[20, 103] |

| S. pombe | na | nd | + | ≈ 0 | + | ≈ 0: Cox2 | [35]. |

| N. crassa | nd | nd | + | nd | [17] | ||

The effects on respiratory complexes have been assessed by spectral, BN-PAGE, activity or growth analyses. Since Oxa1 function is essential in several organisms, the effect of the deletion has been tested by:

deletion of oxa1Sp2 only

heterokaryon analysis

thermosensitive mutant analysis

sh-RNA silencing; na: not applicable; nd not determined. Unless otherwise indicated, arrows refer to activities for the complexes or steady state level for the subunits, when experimentally tested:  : minor increase (less than 50%);

: minor increase (less than 50%);  : minor decrease (less than 50%);

: minor decrease (less than 50%);  : major decrease (more than 50%); ≈ 0 undetectable. NDUFA9 and NDUFV2 are subunits from the peripheral arm of complex I whereas NDUFA9 and NDUFB6 are subunits from the proximal and distal part of the membrane arm of complex I respectively.

: major decrease (more than 50%); ≈ 0 undetectable. NDUFA9 and NDUFV2 are subunits from the peripheral arm of complex I whereas NDUFA9 and NDUFB6 are subunits from the proximal and distal part of the membrane arm of complex I respectively.

In S. pombe two related genes, oxa1Sp1 and oxa1Sp2 have Oxa1-like functions as shown by their ability to complement an S. cerevisiae oxa1 mutant. Only mutations in oxa1Sp2 cause a respiratory deficiency in S. pombe, spectral defects in cytochromes aa3, b and c1, and strongly decreased activity of cytochrome c oxidase and ATPase [38]. Deletion of oxa1Sp1 causes only a slight diminution of activity of these complexes. However, overexpression of oxa1Sp1 can compensate for the absence of oxa1Sp2 in S. pombe. Interestingly, inactivation of both genes is lethal in this petite-negative yeast [38].

Oxa1 function is essential in respiratory-obligate fungi such as N. crassa and P. anserina, where only a single gene is found in the genomes [46, 54]. Strong depletion of N. crassa Oxa1 severely compromises growth and destabilizes the Cox2, Cox3 complex IV subunits as well as the 29.9 and 24 kDa subunits of complex I, providing evidence of a function of Oxa1 in complex I biogenesis [46]. However complex V has not been analyzed in this strain. A role of Oxa1 in complex I biogenesis has also been confirmed by studying a P. anserina thermo sensitive mutant. In this case normal levels of complex V but decreased levels of complexes I and IV were observed, as well as a lowered production of superoxide radicals associated with an increased lifespan [54]. Finally, silencing of the human OXA1L gene in HEK293 cells by short hairpin RNAs resulted in a pronounced decrease in subunit steady-state levels and activity of complex V, and a more modest defect in accumulation of subunits and activity of complex I. Surprisingly, neither complex III nor IV were significantly affected in these Oxa1 deficient human cells [47]. Taken together, the data on pleiotropic effects of depletion or absence of Oxa1 family members in a variety of species suggests biochemical functions for Oxa1 in assembly of integral membrane components of respiratory chain subunits. However the precise physiological roles appear to vary, depending on the organism (Table 1).

4) Analysis of Oxa1 functions in S. cerevisiae mitochondria

The mechanisms by which Oxa1 contributes to assembly of the respiratory chain have been explored by analysis of phenotypes caused by mutations affecting the protein’s distinct domains, identification of suppressors that compensate for defective Oxa1 function, as well as by biochemical studies of the wild-type protein in isolated mitochondria. Biochemical details of Oxa1 function have been difficult to obtain, at least partially owing the lack of any true in vitro system for translation of mitochondrially coded mRNAs on mitochondrial ribosomes. While precise mechanisms have yet to be worked out, it appears clear that wild-type Oxa1 has several distinct activities that contribute to insertion of mitochondrially coded membrane proteins and normal respiratory function.

4)-a Mutagenesis of different Oxa1 domains

Various types of mutations have been introduced into the three Oxa1 domains, i.e. the IMS N-terminus and loop 2, the matrix loop 1 and C-terminus, or the transmembrane (TM) domains (Figure 3). The phenotypic consequences of these changes on membrane insertion and assembly of subunits within the respiratory complexes have been analyzed to examine how the structure relates to the function (Table 2).

Table 2.

List and phenotypes of S. cerevisiae oxa1 mutant

| Mutants | Non-fermentable growth | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δoxa1 | - | [49, 122] | ||

| Location | ||||

| N-ter | oxa1–79 (W106stop) | - | [122] | |

| N-ter/loop2 | F229S-E65G | ts | [90] | |

| Loop2 | ts1402 (L240S) | ts | [49] | |

| Δloop2 (220–244) | - | [55] | ||

| 1 | WW128AA | ts | [55] | |

| 4–5 | ΔTM4–5 (Δ276–314) | - | ||

| Loop1 | Δloop1 (Δ155–197) | + | [55] | |

| R140E | partly cs | |||

| K376* (1–375) | + | [55] | ||

| K353* (1–352) | + | |||

| K332* (1–331) | partly ts, partly cs | |||

| C-tail | 1–317 | - | [56] | |

| Δ55 (1–347) | partly ts | [57] | ||

| Δ83 (1–319) | ts | |||

| C-tail & Loop1 | ΔL1-K332* | - | [55] | |

ts: thermosensitive at 36 or 37°C; cs: cryosensitive at 16°C.

Several substitutions and deletions in the IMS or TM domains appear to be deleterious since in all cases tested they induce either a stringent or thermosensitive respiratory deficient growth. They generally lead to pleiotropic effects on the three complexes except for the WW128AA mutation, which does not affect complex V [55]. The processing of Cox2 is impaired to some extent by all mutations causing a respiratory phenotype, including thermosensitive mutants grown at permissive temperature [19, 55]. A reduction of the steady state level of mutated Oxa1 is often observed, which is probably due to the sensitivity of Oxa1 to proteases [48, 55]. In the case of the oxa1-ts1402 mutation, the level of residual Oxa1 appears to determine the residual activity [48]. However, looking at a larger collection of mutations, there is appears to be no direct correlation between the reduced levels of mutant Oxa1 and the respiratory phenotypes [55].

The effects of mutations located in the matrix domains are complex. Three mutants deleting various portions of the C-terminal part of Oxa1 (Figure 3), and also modifying the mRNA 3’ UTR, were shown to exhibit a very mild (Δ83) to severe respiratory deficiency (1–317, Δ55) [56, 57]. These effects could be mediated by alteration of the protein, or the Puf3 binding site in the mRNA, or both. Premature stop codons (*) introduced at positions K332, K353 and K376, followed by internal deletions that left intact the 3’-UTR and including the Puf3 binding site, had no major effect on the respiratory function as single mutations. However, a double mutant protein with both the C-terminal truncation K332* and the deletion of loop 1 (ΔL1), which alone caused no phenotype, failed to support respiratory grow and caused a 10 fold reduction in complex IV activity as well as reduced activities of complexes III and V [55]. This result suggests the possibility of interacting and redundant functions for these matrix domains.

4)–b- Role in co-translational insertion of mitochondrially-encoded proteins

Chemical crosslinking of mitochondrial translation products labeled in isolated organelles followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-Oxa1 antibody has shown that Oxa1 interacts with nascent polypeptide chains synthesized in mitochondria. Indeed, the precursor form of Cox2 was selectively and transiently associated with Oxa1, indicating an early co-translational interaction prior to pre-Cox2 N-tail export [45]. The inner membrane potential is not needed for this initial association of Oxa1 with the nascent chains [58].

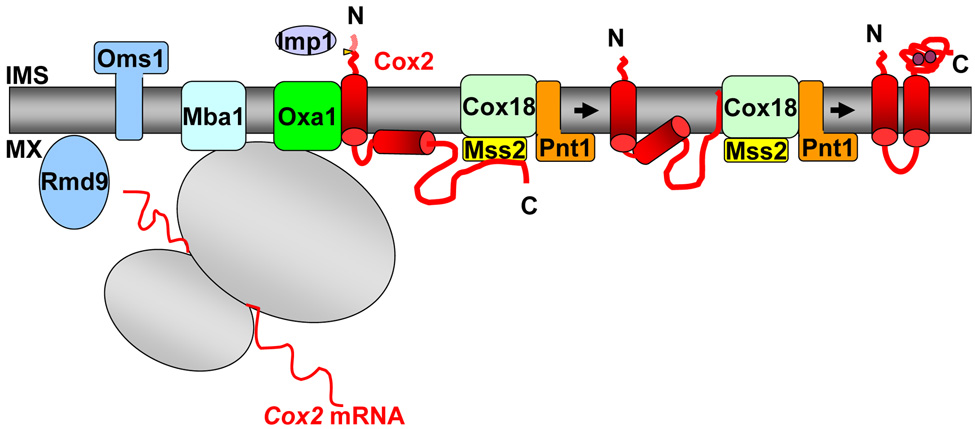

Actively translating ribosomes are largely found at the inner surface of the mitochondrial inner membrane [59], suggesting that ribosomes could be directly involved in establishing Oxa1p-nascent chain interactions. Consistent with this idea, peptide chains stalled on the ribosomes by chloramphenicol treatment remained associated with Oxa1 after elongation arrest, while treatment with puromycin to cause premature release of the nascent chains resulted in significantly reduced association of Oxa1 with the nascent chains [58].Several lines of evidence indicate that Oxa1 physically interacts with the ribosome (Figure 4):first Oxa1 co-fractionates with mitochondrial ribosomes on low-salt sucrose gradients, but only if its C-tail domain is present [56, 57]. Second, the C-terminal domain of Oxa1, which forms a coil structure, binds to mitochondrial ribosomes in vitro [56]. Third, Oxa1 can be crosslinked to Mrp20, which is homologous to bacterial L23, a large ribosomal subunit protein located next to the exit channel of bacterial ribosomes [57].

Figure 4.

Summary of S. cerevisiae mitochondrial proteins that play roles in topogenesis of Cox2 in association with Oxa1 and Cox18. Overproduction of Rmd9 or Oms1 suppresses partially functional alleles of Oxa1. Mba1 may assist in establishing productive interaction between Oxa1 and nascent Cox2, and/or the ribosome. Cleavage of the pre-Cox2 leader peptide by Imp1 in the IMS is required for full assembly of Cox2 and provides an assay for N-tail export by Oxa1. Mss2 and Pnt1 interact with Cox18. Like Cox18, Mss2 is required for Cox2 C-tail export and interacts with newly synthesized Cox2. Purple dots in the fully translocated form of Cox2 indicate copper ions in the C-tail. See text for further discussion and references.

As noted above, different deletions in the C-tail of Oxa1 show intermediate phenotypes, ranging from partial to more stringent impairment of growth on non-fermentable carbon sources (Table 2) and defects in cytochrome c oxidase assembly, but do not prevent assembly of complex V [56, 57]. Whereas the C-tail appears to be dispensable in N. crassa [46], attachment of the Oxa1 C-tail domain to bacterial YidC is required to allow YidC topartially complements the oxa1 deletion in S. cerevisiae (see section 7, [60]). In S. cerevisiae, the simultaneous absence of the C-tail and of loop 1 on the matrix side leads to a complete respiratory defect [55]. This large hydrophilic loop 1 constitutes the second part of the Oxa1 matrix domain, and it may well contribute to Oxa1p-ribosome interactions, although to date there is no direct evidence bearing on this question. It is interesting to note that the chloroplast homologue of Oxa1, Alb3, appears to work in close cooperation and physical association with the chloroplast SRP [5, 61]. While Alb3 has large hydrophilic C-tail and loop 1 domains in the matrix, there is no evidence that it interacts directly with ribosomes.

A possible alternative pathway for productive association of ribosomes with Oxa1 translocation functions may be provided by the nuclearly encoded protein Mba1 [62]. Mba1 has been shown to interact with nascent chains and to bind with the large subunit of the ribosome (Figure 4, [63]). Whereas the absence of Mba1 alone causes almost no phenotype, the absence of Mba1 in strains lacking the Oxa1 C-tail domain causes a dramatic growth defect on non-fermentable medium. In this double mutant, mitochondrial translation products fail to insert and are found in association with the matrix chaperone Hsp70. Thus, the two proteins may cooperate to position the ribosome exit site for efficient insertion of the nascent chains, although no stable interaction between them has been detected [63]. Interestingly, when Oxa1 or Mba1 are overproduced, they both weakly suppress the respiratory deficiency caused by absence of the mAAA-protease subunit, Afg3 [64]. Afg3 in turn is required for the maturation of the mitochondrial ribosomal large subunit protein MrpL32 [65]. Thus the basis of the suppression could be to reinforce the efficiency of co-translational import from an otherwise impaired ribosome.

Finally, Mdm38 has been suggested to play a role similar to that of Oxa1 and Mba1 in coupling mitochondrial translation to membrane insertion [66]. However, the depletion of Mdm38 causes a loss of mitochondrial inner membrane K+/H+ exchange activity and associated osmotic swelling and mitophagy. This cation exchange defect appears to be a primary phenotype caused by the depletion of Mdm38 [67]. Thus the function of this factor in mitochondrial co-translational insertion remains to be established.

4) –c- Oxa1 and export of hydrophilic domains of Cox2p

The most intensively studied substrate of both Oxa1 and Cox18 is mitochondrially coded Cox2, since both proteins are absolutely required for normal insertion of Cox2 in the inner membrane and export of its hydrophilic domains to the IMS. The structure of Cox2 is firmly established by the crystal structure of bovine cytochrome c oxidase [68]: it has two TM segments with two hydrophilic tails in an N-out and C-out topology (Figure 4). The C-terminal domain is 144 residues long and contains copper binding sequences essential for catalytic activity. In S. cerevisiae and N. crassa, the N-terminal tail is preceded by a leader peptide that is cleaved in the IMS by Imp1 (Figure 4, [69–71]. This processing event provides an easy assay for the export of the N-tail across the inner membrane.

Cox2 N-tail export is independent of the inner membrane potential during normal translation within the organelle [72]. However, N-tail export depends upon membrane potential when post-translational export of an in vitro translated precursor that was previously imported into the matrix is examined in isolated mitochondria [73, 74]. Taken together, these findings suggests that membrane bound translation may have a role in driving translocation across the inner-membrane. The export of the large Cox2 C-tail domain was shown to be strictly dependent on the inner membrane potential [72, 74] and may be exported post-translationally [75].

In absence of Oxa1, the pre-Cox2 leader peptide is not translocated to the IMS and therefore not proteolytically processed [19, 49, 50, 52, 72]. The role of Oxa1 in the export of the two hydrophilic tails was studied in vivo by constructing chimeric mitochondrial genes expressing either the Cox2 N-tail with the first TM (67aa) or the full-length Cox2 (251aa) both fused to a mitochondrially encoded version of Arg8 (Arg8mp) as a hydrophilic passenger protein [72]. While the N-tail of the fusion containing only the first TM domain was efficiently exported, the Arg8m moiety remained in the matrix, demonstrating that translocation of the entire protein was not signalled by the leader peptide. Export of the N-tail of this short fusion protein was impaired in absence of Oxa1. Similar results were obtained with the HA-tagged version of Cox2 [75]. Similar experiments with the full length Cox2 fused to Arg8m showed that the C-tail export process could translocate the passenger protein, and that this reaction was also dependent upon Oxa1.

In vitro experiments have confirmed the inhibition of the export of in organello-translated Cox2 in mitochondria purified from the thermosensitive oxa1-ts1402 mutant and exposed to non-permissive temperature: the leader peptide is not processed and pre-Cox2 is protected from protease treatment of mitoplasts [13]. Moreover, chimeric proteins containing the presequence of Neurospora crassa Atp9 fused to the first TM of Cox2 or Atp9 followed by the mouse cytosolic dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) both require Oxa1 for in vitro export of their N-tails following in vitro import [45]. Interestingly, Oxa1 is cross linked with these Cox2 chimeric proteins after their import into wild type mitochondria, showing a physical interaction.

The effect observed on Cox2 C-tail export in the oxa1 mutants could reflect a direct role for Oxa1, or a dependence of C-tail export on prior Oxa1p-dependent N-tail export. Alternatively, the C-tail export defect in oxa1 mutants could be due to indirect pleiotropic effects of Oxa1 deficiency on the respiratory chain that diminish the inner-membrane potential, although C-tail export is not affected in other mutants lacking a respiratory chain. As discussed below, export of the large C-tail domain depends upon Cox18 and other factors that are not required for N-tail export [16, 76, 77], as well as signals contained in the C-tail itself [75].

4)–d- Oxa1 may facilitate the membrane insertion of negatively charged protein sequences

The absence of yeast Oxa1 leads to a tight non-respiratory growth phenotype by preventing Cox2 membrane insertion and reducing the cotranslational insertion of several subunits of the two other respiratory complexes of dual genetic origin (see above). Unexpectedly, single amino acid substitutions in the TM domains of two subunits of complex III, Qcr9 and Cyt1, can partially suppress a complete oxa1 deletion in S. cerevisiae [78, 79]. ATP synthase assembly and activity is fully restored, and 25% of wild type cytochrome c oxidase activity is recovered in the suppressed oxa1 deletion mutants. The membrane insertion of hydrophobic subunits of complex IV and V is restored (e.g. Cox2, Atp4) and maturation of Cox2 is improved demonstrating that the N-tail is correctly inserted. Although Cyt1 is an essential complex III subunit, its catalytic domain is not required for compensation of the Oxa1 deficiency. The small Qcr9 subunit (65 aa) is not required for catalysis, but appears to stabilize complex III, particularly at elevated temperatures [80, 81]. These QCR9 and CYT1 mutations are the only mutations ever reported to bypass the complete absence of Oxa1.

The compensatory mutations generally replace uncharged amino acids with basic ones: leucine to lysine or leucine to arginine in the Cyt1 TM; glycine to arginine in the Qcr9 TM. Since the respiratory complexes are organized into super complexes, such as complexes (III)2IV and (III)2(IV)2 [82, 83], it seems possible that the mutated TM domains of complex III subunits might interact with assembling subunits of the partner complex IV and facilitate their insertion/translocation in absence of Oxa1. Several TM domains of respiratory complex subunits contain negatively charged residues that should make their insertion into the bilayer of the membrane more difficult. This is the case for the second TM domain of Atp9, which contains a highly conserved glutamate residue essential for proton transport in E. coli [84].

Based on these observations, it was proposed that Oxa1 could interact with negatively charged TM domains to facilitate their insertion and lateral exit to the lipid bilayer [79]. It was also proposed that Oxa1 is most important for translocation of negatively charged hydrophilic domains such as the N-tail of pre-Cox2 [85]. Consistent with this idea, in vitro experiments examining the re-export of chimeric proteins imported into the matrix indicate that changing the net charge of the N-terminal part of Atp9 from −1 to +1 decreases the efficiency of export substantially, but also renders it independent of Oxa1 [85].

5) Compensatory mechanisms that enhance reduced Oxa1 activity

Selection for improved respiratory growth of yeast mutants bearing partially functional oxa1 mutations has led to the isolation of a suppressor mutation in a substrate protein (cox2-A189P), as well as wild-type genes (OMS1, RMD9, HAP4) that suppress when over-expressed. The compensatory mechanisms appear to fall into two categories. One group probably acts in the inner membrane at the level of respiratory complex assembly: the main Oxa1 substrate Cox2, and the methyl transferase Oms1. In addition, deletion of the gene YME1, encoding a protease in the inner membrane, restores ATP synthase levels to wild-type although it does not allow respiratory growth. The other group of suppressor genes, HAP4 and RMD9, appear to act more indirectly, at the level of mitochondrial and nuclear gene expression, improving the function of partially functional Oxa1 variants by increasing the level of substrates and/or interacting proteins.

One fascinating suppressor of the oxa1-L240S (ts1402) mutation was found in the mitochondrial gene encoding the major Oxa1 substrate, Cox2 [86]. This mutation modifies the conserved Ala189 of Cox2 into proline and restores the growth of the oxa1-ts1402 mutant on non-fermentable carbon sources at the restrictive temperature. Surprisingly, processing of the leader peptide on the N-tail of Cox2 was not observed during pulse labelling, although it is possible that some mature Cox2 accumulated at steady-state. Although the mechanism of suppression is unclear, it is likely to involve a direct interaction between the variant forms of Cox2 and Oxa1 that increases stability of the mutant Oxa1. Interestingly, the Cox2 residue altered by A189P and the Oxa1 residue altered by L240S are both in domains located in the IMS, consistent with a direct interaction. Unfortunately, this interesting genetic interaction has not been studied further.

Another partner of Oxa1 revealed by suppression is Oms1, a mitochondrial membrane methyltransferase-like protein, whose overproduction partially compensates for oxa1 mutations located in any of the three domains [55]. OMS1 overexpression appears to increase the steady-state level of both mutant and wild-type Oxa1, and this appears to be the basis for suppression. On the other hand, the absence of Oms1 decreases respiratory growth of a temperature-sensitive oxa1 mutant. Oms1 has a single TM domain and exhibits N-in, C-out topology (Figure 4). The conserved methyltransferase motif is in the C-terminal IMS domain. A point mutation in this motif abolishes the suppression, suggesting that the methyltransferase activity is required for the suppression. Thus, it was proposed that Oms1 might methylate form start either a basic amino acid of the IMS domain of Oxa1 or phospholipids of the external face of the inner-membrane, thereby increasing the stability of mutant Oxa1, thereby increasing the overall Oxa1 activity.

Yme1 is an inner membrane protease with a catalytic domain in the IMS, and is known to degrade unassembled Cox2 [87–89]. However, inactivation of the YME1 gene in the Δoxa1 mutant neither restores growth on non-fermentable carbon sources nor increases the steady state levels of cytochrome c oxidase subunits. However, the yme1 deletion fully restores oligomycin-sensitive ATPase activity in a Δoxa1 strain, and stabilizes the ATP synthase membrane subunits that are rapidly degraded in a YME1, Δoxa1 mutant [50]. Apparently, decreased degradation of the unassembled ATP synthase subunits allows their accumulation in the absence of Oxa1, and subsequent Oxa1p-independent assembly. Thus, this result suggests that Oxa1 is not absolutely required to insert ATP synthase subunits into the inner membrane although Oxa1 interacts post-translationally and stably with Atp9 to promote its assembly with Atp6 [52].

Rmd9 is a peripheral inner membrane protein that faces the mitochondrial matrix (Figure 4), which controls the processing/stability of all the mitochondrially coded mRNAs specifying respiratory complex subunits [90]. A small fraction of Rmd9 is associated with the mitochondrial ribosome [91], and it has been proposed, based on genetic interactions, that Rmd9 might convey mitochondrially-encoded mRNAs to specific sites for the co-translational insertion of respiratory subunits. Overexpression of RMD9 both increases the steady state levels of mitochondrially coded mRNAs, and suppresses a double missense oxa1 mutation that alters the IMS domains of Oxa1. Interestingly, the ΔL1-K332* mutation is not suppressed, suggesting that Oxa1 matrix domain is required for the suppression. These data suggest that overproduction of Rmd9 could compensate for reduced membrane insertion of mitochondrial translation products by increasing their rate of synthesis. A similar mechanism could also explain the genetic interaction observed between oxa1 and rmp1 mutants in Podospora anserina [54]. Rmp1 has been proposed to be related to yeast Sls1 [92, 93] which is known to coordinate transcription and translation in S. cerevisiae mitochondria [94].

Finally, over-expression of the nuclear transcriptional activator Hap4 suppresses the ΔL1-K332* mutation, which removes much of the matrix domain of Oxa1, and clearly represents compensation by an indirect mechanism [95]. The yeast Hap2/3/4/5 protein complex, and its human orthologue NF-Y, control the transcription of many nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins [96–99]. Apparently, increased expression of many such nuclear genes compensates for the deficiency of co-translational insertion of mitochondrially coded proteins caused by the oxa1 mutation. This compensatory effect is not specific for oxa1 since HAP4 over-expression also partially compensates for the incomplete respiratory defect due to mutations in the complex IV assembly factor Shy1/Surf1 in both yeast and human fibroblasts[100].

6) Consequences of Cox18 deficiency and analysis of Cox18 function in S. cerevisiae

The COX18 gene was originally identified in a collection of S. cerevisiae nuclear mutations that specifically eliminate cytochrome oxidase activity [101], and later shown to prevent a post-translational step in assembly [20]. A homologous gene required for cytochrome oxidase activity was also identified in Kluyveromyces lactis [102]. In addition sequence homologs were subsequently identified in N. crassa and S. pombe and inactivated [17, 35].

Mutations in cox18 of S. cerevisiae and related genes in other organisms (also called Oxa2 in N. crassa) affect mainly, if not only, complex IV (a possible effect on complex I has not been investigated in N. crassa). Deletion of COX18 leads to a complete lack of cytochrome aa3 in K. lactis, S. cerevisiae and S. pombe [20, 35, 102] (Table 1). The steady-state level of Cox2 is dramatically reduced in cox18 mutants [16], but S35 labeling of mitochondrial proteins shows that this subunit, as well as the other mitochondrial proteins, are still produced, and normal levels of the corresponding RNA are present [20, 35]. This points towards a severe instability of Cox2 in absence of Cox18, clearly demonstrated by pulse-chase experiments [103]. Nevertheless, the S. cerevisiae Cox2 precursor is proteolytically processed in the absence of Cox18 [16, 17, 20], indicating that early steps inCox2 membrane insertion are Cox18p-independent. The absence of N. crassa Cox18 (Oxa2) causes a partial decrease of cytochrome aa3 and a substantial induction of the alternative oxidase, indicative of a defective electron flow through the respiratory chain in the mutant [17].

Thus, despite the sequence similarity between Oxa1 and Cox18 and their role both at posttranslational steps in the assembly of cytochrome c oxidase, striking differences are observed. First, in contrast to Oxa1, Cox18 does not play a role in assembly of other respiratory complexes. Second, Cox18/Oxa2 from N. crassa interacts with Cox2 and also Cox3 in a long-lived manner compared to the transient interaction of Oxa1 with translation products [17]. Third, the function of both proteins in Cox2 biogenesis clearly differ insofar as the pre-Cox2 precursor is not processed in oxa1 mutants but is processed in cox18 mutants. These distinct roles in Cox2 topogenesis are underscored by the fact that overexpression of Oxa1 cannot compensate for the lack of Cox18 [16].

The role of Cox18 in translocation was revealed by the isolation of various point mutations in cox18 in a screen for mutants that failed to export the acidic Cox2 C-terminal domain from the matrix to the IMS [16]. This screen also yielded mutations in the genes MSS2 [77] and PNT1 [76]. Examination of Cox2 modified with an HA epitope at its C-terminus revealed that processing of the pre-Cox2 leader peptide in the IMS did not require Cox18, but export of the HA epitope did. The mss2 mutations similarly prevented C-tail export of wild-type Cox2 without blocking N-tail export, whereas the pnt1 mutations only reduced cytochrome oxidase activity to 58% of wild-type, and thus did not eliminate C-tail export of wild-type Cox2. Contrary to its S. cerevisiae ortholog, the K. lactis Pnt1 is required for cytochrome oxidase assembly in that yeast [76].

Mss2 is peripherally associated with the inner surface of the inner membrane and has a tetratricopeptide motif similar that of the import receptor Tom70 [77]. Closely homologous proteins have not been found outside of budding yeasts. Pnt1 is an integral membrane protein with N- and C-terminal hydrophilic domains exposed in the matrix [76]. Overexpression of PNT1 confers resistance to pentamidine, while deletion increases sensitivity, suggesting that Pnt1 may have other functions in addition to protein translocation [104]. Closely homologous proteins have not been found outside ascomycete fungi.

Both Mss2 and Pnt1 appear to function together with Cox18 since they co-immune precipitate with each other, and their genes exhibit allele-specific genetic interactions [16], see figure 4). These proteins appear to have direct roles in membrane insertion since both Cox18 and Mss2 [75] as well as Cox18/Oxa2 from N. crassa expressed in yeast cells [17]) co-immune precipitate with newly synthesized unassembled Cox2. Interestingly, the Cox2 specie associating with these proteins is full-sized and N-terminally processed. Since Mss2 is located on the inner surface of the inner membrane, this observation strongly suggests that translation of the Cox2 C-terminal domain is completed in the matrix prior to its export to the IMS [75].

The requirements for Cox2 translocation were examined more closely by studying the behavior of truncated proteins bearing the HA epitope tag on their C-termini, encoded by modified mitochondrial genes [75]. One such variant protein, Cox2(1–109)-HA, bearing the Cox2 N-tail and both TM domains, but lacking the large hydrophilic C-tail domain, failed to associate with Mss2, consistent with the idea that Mss2 binds to the C-tail of wild type Cox2. The N-tail of this variant protein was efficiently translocated to the IMS during in vivo pulse labeling in an Oxa1-dependent, Cox18-independent, fashion. Protease protection experiments with unlabeled mitochondria and mitoplasts showed that the C-terminus of Cox2(1–109)-HA accumulated on the IMS side the membrane, in an Oxa1-dependent fashion. Thus, Oxa1 is required for the insertion of the two TM domains, and translocation of the HA epitope, in the absence of the hydrophilic C-tail domain. The N- and C-termini of Cox2(1–109)-HA were efficiently, but not fully, translocated to the IMS in cox18 and mss2 deletion mutants. Thus, neither Cox18 nor Mss2 is required for insertion of the Cox2 TM domains. However, the absence of Cox18 or Mss2 did reduce the efficiency of TM domain insertion, since low levels of Cox2(1–109)-HA with N- and C-termini on the matrix side of the inner membrane were detectable at steady state in the mutants. It remains to be determined whether this indicates a minor direct role for Cox18 and Mss2, or an indirect effect on Oxa1 efficiency caused by their absence.

A second truncated variant of Cox2, lacking the 40 C-terminal residues of the 144 residue acidic C-tail domain, accumulated with its N-terminus exported to the IMS but its C-terminusin the matrix [75]. This confirms that the C-tail is not exported co-translationally after engagement with a translocase, and that acidity alone is not sufficient to signal its export. Instead, it appears that structural features of the C-tail, or a sequence signal that includes residues among the last 40 must be recognized. Interestingly, despite the failure to translocate, this truncated form of Cox2 did associate with Mss2 on the matrix side of the membrane. Thus, Mss2 association alone is insufficient to direct export of the C-tail domain. Elimination of copper binding residues in the Cox2 C-tail domain did not prevent its export, showing that it need not reach its final folded structure to be recognized for translocation. The nature of the signal(s) required for C-tail export, presumably by direct engagement of Cox18, remain to be determined.

7) Functions of the Oxa1-related protein YidC in Escherichia coli

It is not often that discoveries made in the biology of yeast mitochondria lead to the discovery of evolutionarily conserved functions in bacteria. However, the recognition of the important role(s) of yeast Oxa1 in membrane translocation of mitochondrially synthesizedCox2 domains spurred great interest in the function of an E. coli open reading frame encoding the homologous protein termed YidC, beginning with a study of its membrane topology [15]. Since bacterial systems are more amenable to mechanistic analysis using both genetic and in vitro approaches, we have much more detailed information on the mechanism(s) of the bacterial protein than its mitochondrial homologues. These studies have been reviewed in detail [21, 23, 24].

Depending on the substrate protein upon which it is acting, YidC functions together with the SRP and SecYEG translocase [105, 106], with the SRP but not SecYEG [107], or independently of other secretory apparatus components [108, 109]. It seems likely that most YidC molecules function independently of the Sec translocase since YidC is present in E. coli cells at substantially higher levels than SecYEG (and is predominantly located at the poles of growing cells) [26]. Furthermore, YidC can exhibit folding activity independently of a role in membrane insertion [110]. All known substrates of E. coli YidC are integral proteins of the inner membrane. Regardless of how the substrate proteins reach it, YidC appears to promote folding and insertion of transmembrane domains in the bilayer.

Since mitochondria typically lack SecYEG and SRP, the independent activity of YidC is likely to be most revealing for understanding Oxa1 and Cox18. Sec-independent activity of YidC has been studied in the greatest detail using the coat protein of phage Pf3, a 44 amino acid protein with a single TM domain. When expressed in E. coli, the N-terminus of Pf3 coat is translocated to the periplasmic space. This reaction depends upon the presence of YidC, but not the SecYEG translocase, and involves an interaction between YidC and the coat protein TM domain [111]. Furthermore, membrane insertion of Pf3 coat protein can be reconstituted in vitro in proteoliposomes containing only purified YidC [112]. These experiments demonstrate that YidC alone can catalyze the post-translational translocation of hydrophilic coat protein residues through the lipid bilayer and the insertion of the TM domain although other factors are likely to increase the efficiency of the reaction in vivo. Interestingly, a recent low-resolution structure of E. coli YidC obtained by electron cryomicroscopy of 2-dimensional crystals revealed an area of low electron density that has been proposed to be a pore, in its closed state, that could play a role in the translocation or membrane insertion of substrate protein domains [27].

YidC is an essential E. coli protein since depletion of YidC leads to a growth arrest and defects in the assembly of Sec-independent inner membrane proteins [108]. Interestingly, despite the fact that the SecYEG translocase functions together with a portion of YidC, depletion of YidC does not greatly affect the assembly of the majority of inner membrane proteins whose insertion is Sec-dependent. An examination of the physiology of cells undergoing YidC depletion revealed that that they exhibited a stress response that was caused by loss of proton motive force across the inner membrane, and that the loss of membrane potential is the cause of lethality [113]. In a parallel with the phenotype of S.cerevisiae oxa1 mutants, these YidC depleted cells exhibited a marked reduction in the activities of cytochrome bo oxidase (the E. coli enzyme homologous to mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase) and the ATP synthase. Targets for YidC include the CyoA subunit of the cytochrome bo oxidase, similar to mitochondrial Cox2 [114, 115], and the subunit c of ATP synthase, similar to mitochondrial Atp9 [116, 117]. The role of the TM domains of YidC has been highlighted by mutagenesis studies showing the importance of the third domain (TM2 on Figure 1) for membrane protein insertion [25, 118].

The role of YidC in membrane insertion of the CyoA subunit of E. coli cytochrome bo oxidase has been examined in detail [114, 115]. Insertion of the CyoA TM domains, and translocation of its hydrophilic periplasmic domains is strictly dependent upon YidC. However, while insertion of the first TM domain and translocation of the first periplasmic domain required only YidC, insertion of the second TM domain and translocation of the C-terminal periplasmic domain was also dependent upon the Sec translocase. Thus, as previously found for mitochondrial Cox2 [72], distinct mechanisms are required to translocate distinct domains of CyoA. Interestingly, while YidC was required to translocate the C-terminal periplasmic domain of intact CyoA, it was not required for Sec-dependent translocation of a truncated form of CyoA consisting of only the second TM domain and the C-terminal periplasmic domain [114]. Thus, it appears that the absence of C-tail translocation of the intact protein in the absence of YidC may be an indirect effect caused by the failure of N-tail translocation. A detailed biochemical study of these translocation processes should be feasible since the insertion of CyoA can be reconstituted in vitro in proteoliposomes containing only purified YidC, SecYEG, and SecA [119]. These recent results on CyoA yield a picture strikingly similar to the translocation of the N-tail and C-tail of mitochondrial Cox2 in S. cerevisiae, yet intriguingly different. Whereas it is likely, in view of the data on YidC activity, that Cox18 is a true translocase for the C-terminal domain, Oxa1 may be only indirectly involved in this step. However, export of the Cox2 C-tail domain alone has not been tested in mitochondria.

The similarities of YidC, Oxa1, and Cox18 activities in the assembly of the respiratory chain complexes have been thoroughly underscored by studies of in vivo complementation. Chimeric proteins consisting of the E. coli YidC signal sequence and N-terminal periplasmic domain fused to either Oxa1 or Cox18 from S. cerevisiae were able to carry out the essential Sec-independent functions of YidC when expressed in E. coli, allowing growth of cells depleted of wild-type YidC [120, 121]. Thus, the independent functions of this family of translocase proteins important for respiratory complex assembly have been highly conserved in both bacteria and mitochondria. However, as one might expect, neither of these chimeric proteins were able to carry out the functional interactions with the SecYEG translocasenormally observed for wild-type YidC.

In addition YidC TM domains can also carry out the translocase functions necessary for respiratory chain assembly in S. cerevisiae mitochondria [60]. This was established by constructing a chimeric protein in which the mitochondrial targeting signal and N-terminal IMS domain of Oxa1 was fused to the core six TM domains of YidC, deleting the long N-terminal periplasmic YidC domain (see Figure 1). This modified YidC protein was able topartially complement the respiratory growth phenotype of a cox18 deletion mutant, and thus must have been able to translocate the C-tail domain of Cox2. Whether this chimeric protein’s ability to translocate the C-tail domain was dependent upon the partner protein Mss2, that normally works with Cox18 and may function to deliver the Cox2 substrate to it, was not tested. This same chimeric protein was unable to complement the respiratory growth phenotype of an oxa1 mutant. However, addition to this chimeric YidC construct of the matrix localized C-terminal domain of Oxa1, which appears to mediate an interaction between Oxa1 and the mitochondrial ribosome, allowed it to partially compensate for the absence of wild-type Oxa1. This finding is consistent with the idea that ribosome binding by Oxa1 is important for substrate delivery to its translocase domain. Interestingly, the addition of the matrix localized Oxa1 C-terminal domain to the YidC fusion protein destroyed its ability to carry out the Cox18 function. While this effect could have many causes, it is consistent with the likelihood that the Cox18 substrate (the Cox2 C-tail) may be translocated post-translationally [75].

Conclusions

The wide phylogenetic distribution of Oxa1-related proteins appears to reflect both the central role of assembling energy-transducing membrane complexes, and the range of roles in their assembly that Oxa1-related proteins can be adapted to. In different species, Oxa1 and its isoforms appear to assist in the assembly of several different substrate proteins. Recent work on the bacterial protein YidC strongly indicates that it is capable of functioning alone as a translocase for hydrophilic domains and an insertase for TM domains. Thus it is highly likely that the eukaryotic members of this family found in mitochondria and chloroplasts directly catalyze these reactions in a co- and/or posttranslational way. It is presently unclear how Oxa1 recognizes its substrates and whether additional factors assist in this, beyond its direct interaction with mitochondrial ribosomes, demonstrated in S. cerevisiae. Given the apparent co-translational nature of in vivo Oxa1 dependent translocation of the Cox2 N-terminal domain, a detailed mechanistic study of this most criticalOxa1 function will need to await the development of a true in vitro translation system derived from the mitochondrial matrix and inner membrane. However, Oxa1 is also able to assist post-translational insertion and translocation in isolated mitochondria and Cox18 may post-translationally translocate both in vivo and in vitro its only known substrate, the Cox2 C-terminal domain. Thus, biochemical analysis of some of these functions in proteoliposomes may already be possible, taking advantage of the wide variety of mutant forms of S. cerevisiae Oxa1, to examine distinct activities of the protein. It is clear that interpretation of all genetic and biochemical data on Oxa1 and Cox18 will be far more robust when the structure of both proteins in the membrane is be determined.

Acknowledgments

Work in the authors' laboratories has been supported by grants from the Association Française contre les Myopathies (N.B. and G.D.), the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (JCJC06-0163 to N.B. and BLAN06-0234 to G.D.) and the U.S. National Institutes of Health(GM29362 to T.D.F.).

References

- 1.Dolezal P, Likic V, Tachezy J, Lithgow T. Evolution of the molecular machines for protein import into mitochondria. Science. 2006;313:314–318. doi: 10.1126/science.1127895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrmann JM, Neupert W. Protein insertion into the inner membrane of mitochondria. IUBMB Life. 2003;55:219–225. doi: 10.1080/1521654031000123349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang BF, Burger G, O'Kelly CJ, Cedergren R, Golding GB, Lemieux C, Sankoff D, Turmel M, Gray MW. An ancestral mitochondrial DNA resembling a eubacterial genome in miniature. Nature. 1997;387:493–497. doi: 10.1038/387493a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glick BS, Von Heijne G. Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria lack a bacterial-type sec machinery. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2651–2652. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yi L, Dalbey RE. Oxa1/Alb3/YidC system for insertion of membrane proteins in mitochondria, chloroplasts and bacteria. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2005;22:101–111. doi: 10.1080/09687860500041718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pohlschroder M, Hartmann E, Hand NJ, Dilks K, Haddad A. Diversity and evolution of protein translocation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;59:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrmann JM, Funes S. Biogenesis of cytochrome oxidase-sophisticated assembly lines in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Gene. 2005;354:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalbey RE, Chen M. Sec-translocase mediated membrane protein biogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1694:37–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhn A, Stuart R, Henry R, Dalbey RE. The Alb3/Oxa1/YidC protein family: membrane-localized chaperones facilitating membrane protein insertion? Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:510–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stuart R. Insertion of proteins into the inner membrane of mitochondria: the role of the Oxa1 complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1592:79–87. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yen MR, Harley KT, Tseng YH, Saier MH., Jr Phylogenetic and structural analyses of the Oxa1 family of protein translocases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001;204:223–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luirink J, Samuelsson T, de Gier JW. YidC/Oxa1p/Alb3: evolutionarily conserved mediators of membrane protein assembly. FEBS Lett. 2001;501:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02616-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrmann JM, Neupert W, Stuart RA. Insertion into the mitochondrial inner membrane of a polytopic protein, the nuclear-encoded Oxa1p. EMBO J. 1997;16:2217–2226. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang F, Yi L, Moore M, Chen M, Rohl T, Van Wijk KJ, De Gier JW, Henry R, Dalbey RE. Chloroplast YidC homolog Albino3 can functionally complement the bacterial YidC depletion strain and promote membrane insertion of both bacterial and chloroplast thylakoid proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19281–19288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110857200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saaf A, Monne M, de Gier JW, von Heijne G. Membrane topology of the 60-kDa Oxa1p homologue from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30415–30418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saracco SA, Fox TD. Cox18p is required for export of the mitochondrially encoded Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cox2p C-tail and interacts with Pnt1p and Mss2p in the inner membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:1122–1131. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funes S, Nargang FE, Neupert W, Herrmann JM. The Oxa2 protein of Neurospora crassa plays a critical role in the biogenesis of cytochrome oxidase and defines a ubiquitous subbranch of the Oxa1/YidC/Alb3 protein family. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:1853–1861. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kermorgant M, Bonnefoy N, Dujardin G. Oxa1p, which is required for cytochrome c oxidase and ATP synthase complex formation, is embedded in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Curr. Genet. 1997;31:302–307. doi: 10.1007/s002940050209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer W, Bomer U, Pratje E. Mitochondrial inner membrane bound Pet1402 protein is rapidly imported into mitochondria and affects the integrity of the cytochrome oxidase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase complexes. Biol. Chem. 1997;378:1373–1379. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1997.378.11.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Souza RL, Green-Willms NS, Fox TD, Tzagoloff A, Nobrega FG. Cloning and characterization of COX18, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae PET gene required for the assembly of cytochrome oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:14898–14902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.14898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiefer D, Kuhn A. YidC as an essential and multifunctional component in membrane protein assembly. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2007;259:113–138. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(06)59003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gavel Y, von Heijne G. The distribution of charged amino acids in mitochondrial inner-membrane proteins suggests different modes of membrane integration for nuclearly and mitochondrially encoded proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;205:1207–1215. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Gier JW, Luirink J. The ribosome and YidC. New insights into the biogenesis of Escherichia coli inner membrane proteins. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:939–943. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalbey RE, Kuhn A. YidC family members are involved in the membrane insertion, lateral integration, folding, and assembly of membrane proteins. J. Cell Biol. 2004;166:769–774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang F, Chen M, Yi L, de Gier JW, Kuhn A, Dalbey RE. Defining the regions of Escherichia coli YidC that contribute to activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:48965–48972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urbanus ML, Froderberg L, Drew D, Bjork P, de Gier JW, Brunner J, Oudega B, Luirink J. Targeting, insertion, and localization of Escherichia coli YidC. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:12718–12723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200311200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lotz M, Haase W, Kuhlbrandt W, Collinson I. Projection structure of YidC: a conserved mediator of membrane protein assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;375:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver DC, Paetzel M. Crystal structure of the major periplasmic domain of the bacterial membrane protein assembly facilitator YidC. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:5208–5216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravaud S, Stjepanovic G, Wild K, Sinning I. The crystal structure of the periplasmic domain of the Escherichia coli membrane protein insertase YidC contains a conserved substrate binding cleft. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:9350–9358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710493200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravaud S, Wild K, Sinning I. Purification, crystallization and preliminary structural characterization of the periplasmic domain P1 of the Escherichia colimembrane-protein insertase YidC. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2008;64:144–148. doi: 10.1107/S1744309108002364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie K, Kiefer D, Nagler G, Dalbey RE, Kuhn A. Different regions of the nonconserved large periplasmic domain of Escherichia coli YidC are involved in the SecF interaction and membrane insertase activity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13401–13408. doi: 10.1021/bi060826z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tjalsma H, Bron S, van Dijl JM. Complementary impact of paralogous Oxa1-like proteins of Bacillus subtilis on post-translocational stages in protein secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15622–15632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Giezen M, Tovar J. Degenerate mitochondria. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:525–530. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marathe SV, McEwen JE. Expression of the divergent transcription unit containing the yeast PET122 and OXA1 genes. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 1999;47:971–977. doi: 10.1080/15216549900202093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaisne M, Bonnefoy N. The COX18 gene, involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, is functionally conserved and tightly regulated in humans and fission yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:869–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O'Shea EK, Weissman JS. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonnefoy N, Chalvet F, Hamel P, Slonimski PP, Dujardin G. OXA1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae nuclear gene whose sequence is conserved from prokaryotes to eukaryotes controls cytochrome oxidase biogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;239:201–212. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonnefoy N, Kermorgant M, Groudinsky O, Dujardin G. The respiratory gene OXA1 has two fission yeast orthologues which together encode a function essential for cellular viability. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35:1135–1145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerber AP, Herschlag D, Brown PO. Extensive association of functionally and cytotopically related mRNAs with Puf family RNA-binding proteins in yeast. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Rodriguez LJ, Gay AC, Pon LA. Puf3p, a Pumilio family RNA binding protein, localizes to mitochondria and regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and motility in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 2007;176:197–207. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sylvestre J, Margeot A, Jacq C, Dujardin G, Corral-Debrinski M. The role of the 3' untranslated region in mRNA sorting to the vicinity of mitochondria is conserved from yeast to human cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:3848–3856. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia M, Darzacq X, Delaveau T, Jourdren L, Singer RH, Jacq C. Mitochondria-associated yeast mRNAs and the biogenesis of molecular complexes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:362–368. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frazier AE, Chacinska A, Truscott KN, Guiard B, Pfanner N, Rehling P. Mitochondria use different mechanisms for transport of multispanning membrane proteins through the intermembrane space. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:7818–7828. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7818-7828.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reif S, Randelj O, Domanska G, Dian EA, Krimmer T, Motz C, Rassow J. Conserved mechanism of Oxa1 insertion into the mitochondrial inner membrane. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;354:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hell K, Herrmann JM, Pratje E, Neupert W, Stuart RA. Oxa1p, an essential component of the N-tail protein export machinery in mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:2250–2255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nargang FE, Preuss M, Neupert W, Herrmann JM. The Oxa1 protein forms a homooligomeric complex and is an essential part of the mitochondrial export translocase in Neurospora crassa. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:12846–12853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stiburek L, Fornuskova D, Wenchich L, Pejznochova M, Hansikova H, Zeman J. Knockdown of human Oxa1l impairs the biogenesis of F1Fo-ATP synthase and NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;374:506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaser M, Kambacheld M, Kisters-Woike B, Langer T. Oma1, a novel membrane-bound metallopeptidase in mitochondria with activities overlapping with the m-AAA protease. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:46414–46423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bauer M, Behrens M, Esser K, Michaelis G, Pratje E. PET1402, a nuclear gene required for proteolytic processing of cytochrome oxidase subunit 2 in yeast. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1994;245:272–278. doi: 10.1007/BF00290106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lemaire C, Hamel P, Velours J, Dujardin G. Absence of the mitochondrial AAA protease Yme1p restores F0-ATPase subunit accumulation in an oxa1 deletion mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:23471–23475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Altamura N, Capitanio N, Bonnefoy N, Papa S, Dujardin G. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae OXA1 gene is required for the correct assembly of cytochrome c oxidase and oligomycin-sensitive ATP synthase. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:111–115. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jia L, Dienhart MK, Stuart RA. Oxa1 directly interacts with Atp9 and mediates its assembly into the mitochondrial F1Fo-ATP synthase complex. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:1897–1908. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stock D, Gibbons C, Arechaga I, Leslie AG, Walker JE. The rotary mechanism of ATP synthase. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:672–679. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sellem CH, Lemaire C, Lorin S, Dujardin G, Sainsard-Chanet A. Interaction between the oxa1 and rmp1 genes modulates respiratory complex assembly and life span in Podospora anserina. Genetics. 2005;169:1379–1389. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lemaire C, Guibet-Grandmougin F, Angles D, Dujardin G, Bonnefoy N. A yeast mitochondrial membrane methyltransferase-like protein can compensate for oxa1 mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:47464–47472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szyrach G, Ott M, Bonnefoy N, Neupert W, Herrmann JM. Ribosome binding to the Oxa1 complex facilitates co-translational protein insertion in mitochondria. EMBO J. 2003;22:6448–6457. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jia L, Dienhart M, Schramp M, McCauley M, Hell K, Stuart RA. Yeast Oxa1 interacts with mitochondrial ribosomes: the importance of the C-terminal region of Oxa1. EMBO J. 2003;22:6438–6447. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hell K, Neupert W, Stuart RA. Oxa1p acts as a general membrane insertion machinery for proteins encoded by mitochondrial DNA. EMBO J. 2001;20:1281–1288. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vignais PV, Huet J, Andre J. Isolation and characterization of ribosomes from yeast mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1969;3:177–181. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(69)80128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Preuss M, Ott M, Funes S, Luirink J, Herrmann JM. Evolution of mitochondrial Oxa proteins from bacterial YidC. Inherited and acquired functions of a conserved protein insertion machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13004–13011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moore M, Goforth RL, Mori H, Henry R. Functional interaction of chloroplast SRP/FtsY with the ALB3 translocase in thylakoids: substrate not required. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:1245–1254. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Preuss M, Leonhard K, Hell K, Stuart RA, Neupert W, Herrmann JM. Mba1, a novel component of the mitochondrial protein export machinery of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:1085–1096. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ott M, Prestele M, Bauerschmitt H, Funes S, Bonnefoy N, Herrmann JM. Mba1, a membrane-associated ribosome receptor in mitochondria. EMBO J. 2006;25:1603–1610. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rep M, Nooy J, Guelin E, Grivell LA. Three genes for mitochondrial proteins suppress null-mutations in both Afg3 and Rca1 when over-expressed. Curr. Genet. 1996;30:206–211. doi: 10.1007/s002940050122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nolden M, Ehses S, Koppen M, Bernacchia A, Rugarli EI, Langer T. The m-AAA protease defective in hereditary spastic paraplegia controls ribosome assembly in mitochondria. Cell. 2005;123:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frazier AE, Taylor RD, Mick DU, Warscheid B, Stoepel N, Meyer HE, Ryan MT, Guiard B, Rehling P. Mdm38 interacts with ribosomes and is a component of the mitochondrial protein export machinery. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:553–564. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nowikovsky K, Reipert S, Devenish RJ, Schweyen RJ. Mdm38 protein depletion causes loss of mitochondrial K+/H+ exchange activity, osmotic swelling and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1647–1656. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsukihara T, Aoyama H, Yamashita E, Tomizaki T, Yamaguchi H, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yoshikawa S. The whole structure of the 13-subunit oxidized cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 A. Science. 1996;272:1136–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pratje E, Guiard B. One nuclear gene controls the removal of transient presequences from two yeast proteins: one encoded by the nuclear the other by the mitochondrial genome. EMBO J. 1986;5:1313–1317. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nunnari J, Fox TD, Walter P. A mitochondrial protease with two catalytic subunits of nonoverlapping specificities. Science. 1993;262:1997–2004. doi: 10.1126/science.8266095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jan PS, Esser K, Pratje E, Michaelis G. Som1, a third component of the yeast mitochondrial inner membrane peptidase complex that contains Imp1 and Imp2. Mol. Gen. Genet. 2000;263:483–491. doi: 10.1007/s004380051192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.He S, Fox TD. Membrane translocation of mitochondrially coded Cox2p: distinct requirements for export of N and C termini and dependence on the conserved protein Oxa1p. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:1449–1460. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Clarkson GH, Poyton RO. A role for membrane potential in the biogenesis of cytochrome c oxidase subunit II, a mitochondrial gene product. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:10114–10118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Herrmann JM, Koll H, Cook RA, Neupert W, Stuart RA. Topogenesis of cytochrome oxidase subunit II. Mechanisms of protein export from the mitochondrial matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27079–27086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fiumera HL, Broadley SA, Fox TD. Translocation of mitochondrially synthesized Cox2 domains from the matrix to the intermembrane space. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:4664–4673. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01955-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.He S, Fox TD. Mutations affecting a yeast mitochondrial inner membrane protein, Pnt1p, block export of a mitochondrially synthesized fusion protein from the matrix. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:6598–6607. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Broadley SA, Demlow CM, Fox TD. Peripheral mitochondrial inner membrane protein, Mss2p, required for export of the mitochondrially coded Cox2p C tail in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:7663–7672. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.22.7663-7672.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]