What are the determinants of health and of well-being? Income and wealth are clearly part of the story, but does access to health care have a large independent effect, as the advocates of more investment in health care, such as the World Health Organization’s Commission on Macroeconomics and Health (Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, 2001), have argued? This paper reports on a recent survey in a poor rural area of the state of Rajasthan in India intended to shed some light on this issue, where there was an attempt to use a set of interlocking surveys to collect data on health and economic status, as well as the public and private provision of health care.

1. The Udaipur Rural Health Survey

We collected data between January 2002 and August 2003 in 100 hamlets in Udaipur district, Rajasthan, India. Udaipur is one of the poorest districts of India, with a large tribal population and an unusually high level of female illiteracy (at the time of the 1991 census, only 5 percent of women were literate in rural Udaipur). The survey was conducted in collaboration with two local institutions: Seva Mandir, an NGO that works, among other things, on health in rural Udaipur, and Vidhya Bhawan, a consortium of schools, teaching colleges, and agricultural colleges, who supervised the administration of the survey. The sample frame consisted of all the hamlets in the 362 villages where Seva Mandir operates in at least one hamlet.1 The sample was stratified according to access to a road (out of the 100 hamlets, 50 hamlets are at least 500 meters away from a road). Hamlets within each stratum were selected randomly, with a probability of being selected proportional to the hamlet population. We then selected 10 households in each of 100 hamlets using simple random sampling, and all individuals were surveyed within each household.

The data collected include four components: (i) a village survey, where we obtained a village census, a description of the village’s physical infrastructure, and a list of health facilities commonly used by villagers (100 villages); (ii) a facility survey, where we collected detailed information on activities, types and cost of treatment, referrals, availability of medication and quality of physical infrastructure in all public facilities (143 facilities) serving the sample villages, all “modern” private facilities mentioned in the village surveys or in the household interviews (we have surveyed 85 facilities so far, but this survey is ongoing), and a sample of the traditional healers mentioned in the village surveys (225 facilities were surveyed); (iii) a weekly visit to all public facilities serving the villages (143 facilities in total, with 49 visits per facility on average) where we checked whether the facility was open, and if so, who was present; and (iv) a household and individual survey, covering 5,759 individuals in 1,024 households. The data cover information on economic well-being, integration in society, education, fertility history, perception of health and subjective well-being, and experience with the health system (public and private), as well as a small array of direct measures of health (hemoglobin, blood pressure, weight and height, peak flow meter measurement).

II Health and Wealth in Rural Udaipur

The households in the Udaipur survey are poor, even by the standards of rural Rajasthan. Their average per capita household expenditure is 470 rupees, and more than 40 percent of the people live in households below the official poverty line, compared with only 13 percent in rural Rajasthan in the latest official counts for 1999–2000. Only 46 percent of adult mates (age 14 and older) and 11 percent of adult females report themselves as literate. Of the 27 percent of adults with any education, three-quarters completed standard eight or less. The survey households have little in the way of household durable goods, and only 21 percent have electricity.

In terms of measures of health, 80 percent of adult women and 27 percent of the adult men have hemoglobin levels below 12 grams per deciliter; 5 percent of adult women and 1 percent of adult men have hemoglobin levels below 8 grams per deciliter. Using a standard cutoff for anemia (11 g/dl for women, and 13 g/dl for men), men are almost as likely (51 percent) to be anemic as women (56 percent) and older women are not less anemic than younger ones, suggesting that diet is a key factor. The average body mass index (BMI) is 17.8 among adult men, and 18.1 among adult women; 93 percent of adult men and 88 percent of adult women have a BMI less than 21, considered to be the cutoff for low nutrition in the United States (Robert Fogel, 1997). Symptoms of disease are widespread, and adults self-report a wide range of symptoms: one-third reported cold symptoms in the last 30 days, and 12 percent say the condition was serious; 33 percent reported fever (14 percent, serious), 42 percent reported “body ache” (20 percent, serious), 23 percent reported fatigue (7 percent, serious), 14 percent problems with vision (3 percent, serious), 42 percent headaches (15 percent, serious), 33 percent back aches (10 percent, serious), 23 percent upper abdominal pain (9 percent, serious), and 11 percent chest pains (4 percent, serious); 11 percent had experienced weight loss (2 percent, serious). Few people reported difficulties with personal care, such as bathing, dressing, or eating, but many reported difficulty with the physical activities that are required to earn a living in agriculture. Thirty percent or more would have difficulty walking five kilometers, drawing water from a well, or working unaided in the fields; 18–20 percent have difficulty squatting or standing up from a sitting position.

Yet when asked to report their own health status, shown a ladder with 10 rungs, 62 percent place themselves on rungs 5–8 (more is better), and less than 7 percent place themselves on one of the bottom two rungs. Unsurprisingly, older people report worse health. Also, women at all ages consistently report worse health than men, which appears to be a worldwide phenomenon. Nor do our life-satisfaction measures show any great dissatisfaction with life: on a five-point scale, 46 percent take the middle value, and only 9 percent say their life makes them generally unhappy. Such results are similar to those for rich countries; for example, in the United States, more than a half of respondents report themselves as a three (quite happy) on a four-point scale, and 8.5 percent report themselves as unhappy or very unhappy. These people are presumably adapted to the sickness that they experience, in that they do not see themselves as particularly unhealthy or, perhaps in consequence, unhappy. Yet they are not adapted in the same way to their financial status, which was also self-reported on a ten-rung ladder. Here the modal response was the bottom rung, and more than 70 percent of people live in households that are self-reported as living on the bottom three rungs.

What about the relation between health and wealth? The standard measure of economic status in India is household total per capita expenditure (PCE), which we collected using an abbreviated consumption questionnaire previously used by the National Sample Survey in the 1999–2000 survey. In Table 1, we show self-reported health, number of symptoms reported in the last 30 days, BMI, the fraction of individuals with a hemoglobin count below 12, peak flow meter, and the fractions of individuals with high blood pressure and low blood pressure, broken down by third of the per capita income distribution. Although the pattern is not always consistent across the groups, individuals in the lower third of the per capita income distribution have, on average, a lower level of self-reported health, lower BMI, and lower lung capacity, and they are more likely to have a hemoglobin count below 12 than those in the upper third. Individuals in the upper third report the most symptoms over the last 30 days, perhaps because they are more aware of their own health status; there is a long tradition in the Indian and developing country literature of better-off people reporting more sickness (see e.g., Christopher Murray and Lincoln C. Chen, 1992; Amartya K. Sen, 2002).

TABLE 1.

SELECTED HEALTH INDICATIORS, BY POSITION IN THE PER CAPITA MONTHLY EXPENDITURE DISTRIBUTION

| Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Bottom third | Middle third | Top third |

| Reported health status | 5.87 | 5.98 | 6.03 |

| No. symptoms self-reported in last 30 days | 3.89 | 3.73 | 3.96 |

| BMI | 17.85 | 17.83 | 18.31 |

| Hemoglobin below 12 g/dl | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.51 |

| Peak flow meter reading | 314.76 | 317.67 | 316.39 |

| High blood pressure | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| Low blood pressure | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

Notes: Means reported are based on data collected by the authors from 1,024 households. See text for survey and variable description.

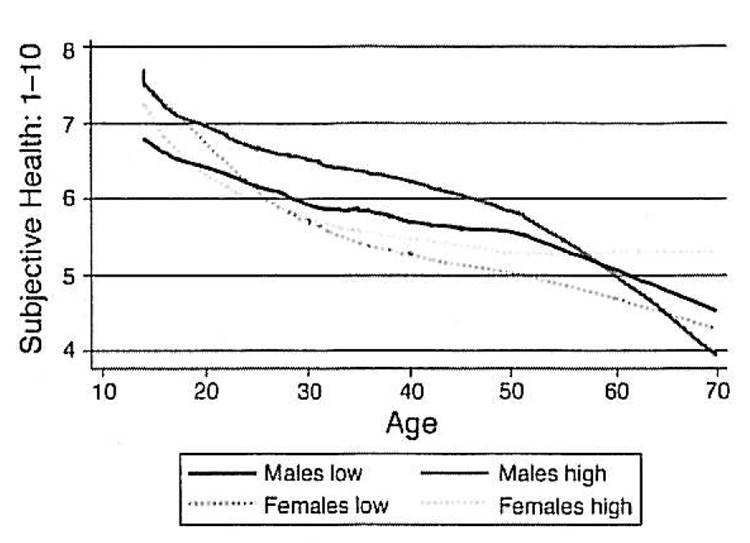

Figure 1 shows self-reported health as a function of age and gender, comparing the bottom three deciles with the top three deciles. Self-reported health is better in the higher deciles, though the effect is much stronger for men than for women, for whom there is little or no PCE gradient. The steeper gradient for men may be an indication that some of this relationship is driven by the effect of health on income, since we would observe such a relation if men earn more because they are stronger.

FIGURE 1.

LOWESS PLOTS OF SELF-REPORTED HEALTH STATUS, By SEX AGE, AND PCE

We investigate this further in Table 2, in which the self-reported health status is regressed on age, age-squared, and measures of economic status. Our regressions show that, conditional on total household expenditure, neither health nor happiness was reduced by household size, so we report regressions using total household expenditure rather than per capita household expenditure. We also show the results of using the household’s own report of its financial status on a 10-point scale; this measure is typically a better predictor of health and happiness than are expenditure measures. We also constructed a dummy for each adult indicating whether that person had earnings from work and then regressed self-reported health status on each measure of economic status and its inter-action with the worker dummy. As anticipated, the slope of the regression of health on economic status is higher for earners, by about one-fifth for total household expenditure, and by a factor of 2 for the self-reported economic status measure. Column 2 shows the same regression with an indicator for having a hemoglobin level below 12 g/dl as the dependent variable. In both cases, we also find the inter-action between the income-earner dummy and household welfare status to be negative. These findings are consistent with the idea that at least some of the gradient comes from the effects of health on earnings, although they could also indicate that the nutrition and health inputs received by workers are more income-elastic than those of nonworkers. The last column of the table shows parallel regressions with happiness rather than health as the dependent variable. A concern with these subjective variables is that there is a personality-based (and reality-free) component that is common to both the happiness and the health measure, and which could be different for workers and nonworkers. But these regressions, unlike those for self-reported health status or anemia, show no effects of the interaction term; there appears to be some suggestive evidence of a feedback from health to earnings, but not from happiness to earnings.

TABLE 2.

HEALTH, HAPPINESS, AND ECONOMIC STATUS

| Independent variable | Self-reported health status | Hemoglobin level below 12g/dl | Self-reported happiness |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Regressions Using Subjective Economic Status (SES): | |||

| SES | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.14 |

| (4.1) | (0.8) | (11.6) | |

| SES × worker | 0.14 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| (4.7) | (4.3) | (0.9) | |

| B. Regressions Using Total Household Expenditure (THE): | |||

| In(THE) | 0.27 | −0.06 | 0.23 |

| (3.6) | (3.2) | (7.4) | |

| In(THE) × worker | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.003 |

| (4.0) | (4.5) | (0.5) | |

Notes: Regressions also include age and age-squared. Absolute t statistics are reported in parentheses below the coefficients.

III. Health Care and Health in Rural Udaipur

The combination of the public facility survey, a private facility survey, and the household survey casts light on the state of public and private health care provision in Udaipur district and its place in people’s lives. The picture is bleak. Starting with the public health facility surveys, the weekly absenteeism survey reveals that, on average, 45 percent of medical personnel are absent in subcenters and aid posts, and 36 percent are absent in the (larger) primary health centers and community health centers.2 These high rates of absences are not due to staff attending patients; whenever the nurse was absent from a subcenter, we made sure to look for her in the community. Since subcenters are often staffed by only one nurse, this high absenteeism means that these facilities are often closed: we found the subcenters closed 56 percent of the time during regular opening hours. Only in 12 percent of the cases was the nurse to be found in one of the villages served by her subcenter. The situation does not seem to be specific to Udaipur: these results are similar to the absenteeism rate found in nationally representative surveys in India and Bangladesh (Nazmul Chaudhury and Jeffrey Hammer, 2003; Chaudhuty et al., 2003).

The weekly survey allows us to assess whether there is any pattern in center opening. For each center, we ran a regression of the fraction of personnel missing on dummies for each day of the week, time of the day, and seasonal dummies. We find that the day-of-the-week dummies are significant at the 5-percent level in only 7 percent of the regressions, and the time-of-the-day dummies are significant only in 10 percent of the regressions. The public facilities are thus open infrequently and unpredictably, leaving people to guess whether it is worth their while walking for over half an hour to cover the 1.4 miles that separate the average village in our sample from the closest public health facility.

Faced with this situation, do households forgo the consumption of health care? Far from it: Households spend a considerable fraction of their monthly budget on health care. In the expenditure survey, households report spending 7.3 percent of their budget on health care. Households in the top third of the per capita income distribution spend 11 percent of the budget on health care. Visits to public facilities are generally not free (the households spend on average 110 rupees when they visit a health facility) even though medicines and services are supposed to be free, when they are “available.” Even those who are officially designated as “below the poverty line,” who are entitled to completely free care, end up paying only 40 percent less in public facilities than others. Visits to traditional healers (“bhopas”) account for 19 percent of the visits and 12 percent of the health expenditure of the average household. Poorer households are more likely to visit the bllopas than richer households (27 percent of the visits and 19 percent of the average monthly health expenditure), especially in villages where the public health facilities are closed most often: in the villages served by the third of facilities that are closed the most often, 29 percent of the health visits of the poor are to bhopas (as against 18 percent in villages served by facilities that are the most open). Irrespective of whether the public facility serving the village is mostly closed or not, visits to other private providers account for 57 percent of the visits and 65 percent of the costs.

Health personnel in the private sector are often untrained and largely unregulated, even if we leave out the bhopas. According to their own report, 41 percent of those who called themselves “doctors” do not have a medical degree, 18 percent have no medical training whatsoever, and 17 percent have not graduated from high school.3 Given the symptoms reported by the villagers, the treatment received in these facilities appears rather heterodox: in 68 percent of the visits to a private facility the patient is given an injection; in 12 percent of the visits he is given a drip. A test is performed in only 3 percent of the visits. In public facilities, they are somewhat less likely to get an injection or a drip (32 percent and 6 percent, respectively) but no more likely to be tested.

These data paint a fairly bleak picture: villagers’ health is poor; the quality of the public service is abysmal; and private providers who are unregulated and, for the most part, unqualified provide the bulk of health care in the area. Having low-quality public facilities is correlated with some direct health measures. Lung capacity and BMI are lower where the facilities are worse, after controlling for household per capita monthly expenditure, distance from the road, age, and gender. Yet, as we have seen for the self-reported health status, villagers not only do not perceive their health as particularly bad, but they seem fairly content with what they are getting: 81 percent report that their last visit to a private facility made them feel better, and 75 percent report that their last visit to a public facility made them feel better. Self-reported health and well-being measures, as well as the number of symptoms reported in the last month, appear to be uncorrelated with the quality of the public facilities. The quality of the health services may impact health but does not seem to impact people’s perception of their own health or of the health-care system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Seva Mandir for invaluable help in accessing their villages and Vidhya Bhawan for hosting the research team. Special thanks go to Neelima Khetan of Seva Mandir, Hardy K. Dewan of Vidhya Bhawan, and Drs. Renu and Baxi from the health units of Seva Mandir. We thank Annie Duflo, Neeraj Negi, and Callie Scott for their superb work in supervising the survey, and the entire health project team for their tireless effort. Callie Scott also supervised data entry and cleaning, and she performed much of the data analysis underlying this paper. We are grateful to Lant Pritchell and Norbert Schady for excellent comments. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Center for Health and Wellbeing, Princeton University, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Institute of Aging through the National Bureau of Economic Research, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and the World Bank.

Footnotes

A hamlet is a set of houses that are close together, share a community center, and constitute a separate entity. A village is an administrative boundary. A village comprises 1–15 hamlets (the mean number of hamlets in a village is 5.6). Seva Mandir in general operates in the poorest hamlets within a given village.

A subcenter serves 3,600 individuals and is usually staffed by one nurse. A primary health center serves 48,000 individuals and has on average 5.8 medical personnel appointed, including 1.5 doctors.

Based on an incomplete sample of 72 doctors. This is similar to a survey of private providers in Delhi (Jishnu Das, 2001), which found that 41 percent of the providers were unqualified.

Contributor Information

Abhijit Banerjee, Department of Economics and Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544.

Angus Deaton, Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139.

Esther Duflo, Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139.

REFERENCES

- Chaudhury Nazmul, Hammer Jeffrey. Mimeo, Development Research Group. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2003. Ghost Doctors: Absenteeism in Bangladeshi Health Facilities. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury Nazmul, Hammer Jeffrey, Kremer Michael, Muralidharan Kartik, Rogers Halsey. Mimeo, Development Research Group. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2003. Teachers and Health Care Providers Absenteeism: A Multi-Country Study. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Macroeconomics and health: Investing in health for economic development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Das Jishnu. Ph.D. dissertation. Harvard University; 2001. Three Essays on the Provision and Use of Services in Low Income Countries. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel Robert W. New Findings on Secular Trends in Nutrition and Mortality: Some Implications for Population Theory. In: Oded Stark, Mark Rosenzweig., editors. Handbook of population and family economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1997. pp. 433–481. [Google Scholar]

- Murray Christopher JL, Chen Lincoln C. Understanding Morbidity Change. Population and Development Review. 1992 Sep;18(3):481–503. [Google Scholar]

- Sen Amartya K. Health: Perception versus Observation. British Medical Journal. 2002 Apr;324(7342):860–861. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]