Abstract

Diffuse parenchymal lung diseases are a group of disorders that involve the space between the epithelial and endothelial basement membranes and are generally segregated into four major categories. These include the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, which are further categorized into seven clinical/radiologic/pathologic subsets. These disorders generally share a common pattern of physiologic abnormality characterized by a restrictive ventilatory defect and reduced diffusing capacity (DLCO). Pulmonary function testing is often used and recommended in their assessment and management. The potential clinical application of physiologic testing includes to aid in diagnosis, although its value in differential diagnosis is limited. Pulmonary function testing also aids in establishing disease severity and in defining prognosis. In nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, severely decreased DLCO has proven valuable in this regard. Similarly, exertional desaturation to less than 88% at baseline testing and a decrease in FVC (greater than 10%) over the course of short-term follow-up identify patients at particular risk of mortality. Finally, physiologic testing, especially spirometry and DLCO, have demonstrated value in monitoring response to therapy and identifying disease progression.

Keywords: nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, prognosis, pulmonary function, survival

Diffuse parenchymal lung diseases (DPLDs) are a group of disorders that involve the space between the epithelial and endothelial basement membranes (1). The clinical, physiologic, and radiographic manifestations are often similar. Guidelines recommend the use of four categories for DPLDs: (1) DPLD of known cause, (2) granulomatous DPLD, (3) rare DPLD with well-defined clinicopathologic features, and (4) idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) (1). IIPs are further subdivided into usual interstitial pneumonia (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [IPF], if the UIP is idiopathic), desquamative interstitial pneumonia, respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease, acute interstitial pneumonia, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (1). This work reviews the role of physiologic testing in IIPs with a focus on the clinical implications and application of such testing. A detailed mechanistic discussion of the pathophysiology of these disorders is not presented.

PHYSIOLOGIC ABNORMALITIES

The majority of DPLDs share a common pattern of physiologic abnormality (2). A restrictive ventilatory defect is typical with a downward and rightward shift of the static expiratory pressure–volume curve. Lung recoil is increased over the range of the inspiratory capacity with a reduction of total lung capacity (TLC) and vital capacity (VC) (3–5), whereas the coefficient of retraction (pleural pressure at TLC/lung volume at TLC) is elevated compared with normal subjects (3, 6). As a result of these changes, static lung volumes are typically reduced in DPLDs. The VC is reduced, although the FRC is usually decreased to a relatively lesser extent (2). The TLC is usually less severely affected because of the normal, or near normal, chest wall recoil and the preserved inspiratory muscle function in most patients (7, 8). The residual volume (RV) is well preserved in most cases, although the RV/TLC ratio is frequently increased (7, 9). Spirometric measures of airway function are usually well preserved in DPLD although small airway abnormalities, of unclear clinical significance, have been reported in some DPLDs (2).

Several groups have described atypical, physiologic presentations in patients with IPF with preserved lung volumes (10–12). Cherniack and colleagues confirmed a higher FVC and TLC in smokers than in never-smokers (10), while Doherty and coworkers described a normal VC (more than 80% predicted) in 21 of 48 patients with IPF (11). Those with preserved VC were more likely to be male, current smokers (57 vs. 22%), have a heavier lifetime history of cigarette smoking, and exhibit greater concomitant emphysema on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan. Similar data were reported by Erbes and colleagues (13) and, most recently, by Cottin and coworkers (12). It is evident that smoking history alters the physiologic presentation of IPF, likely resulting from the confounding effect of emphysema.

Diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DlCO) is typically reduced in DPLD to a greater extent than the lung volume at which it is measured (2). Furthermore, the DlCO appears to be decreased to a greater extent with IPF than for other DPLDs (14, 15). Characteristic arterial blood gas abnormalities in IPF include resting hypoxemia and increased alveolar–arterial oxygen pressure difference (P[a–a]O2] (2). These abnormalities are more evident during exercise, where hypoxemia is quite prevalent (6, 16, 17). Additional abnormalities during exercise are noted, including reduced peak oxygen consumption, diminished ventilatory reserve, high-frequency/low tidal volume breathing pattern, and high submaximal ventilation related in part to elevated physiologic dead space and arterial desaturation (2). Exercise-induced gas exchange can be readily identified by simple testing such as the 6-min walk study. One group has reported 6-min walk test results in IPF and NSIP (18). Table 1 illustrates the differences in exertional desaturation between the two groups. It is evident that both groups experience a similar degree of exertional desaturation.

TABLE 1.

CHANGES DURING 6-MINUTE WALK TEST IN PATIENTS WITH IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY FIBROSIS AND PATIENTS WITH NONSPECIFIC INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA

| 6-Minute Walk Test Parameter | IPF (n = 83) | NSIP (n = 22) |

|---|---|---|

| Change in saturation (%), mean ± SD | 7.1 ± 4.1 | 5.7 ± 4.1 |

| Trough saturation < 88% during room air test, n (% of patients) | 44 (53%) | 8 (36%) |

| Change in saturation > 2%, n experiencing (% of patients) | 75 (90%) | 20 (90%) |

| Change in saturation > 4%, n experiencing (% of patients) | 66 (80%) | 14 (64%) |

Definition of abbreviations: IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; NSIP = nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.

Data from Reference 18.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

Pulmonary function testing is often used and recommended in the management of patients with DPLD (19). Potential clinical applications include: (1) aiding in diagnosis; (2) establishing disease severity; (3) defining prognosis; and (4) monitoring response to therapy and disease progression. We review the published data supporting or refuting these recommendations for IIPs.

Can Pulmonary Function Testing Aid in Diagnosing IIPs?

It is evident that the physiologic presentation of DPLDs, while typical, is not specific. As such, pulmonary function tests (PFTs) should be used in conjunction with clinical, radiographic, and histologic information in assuring an accurate diagnosis. On the other hand, in patients with appropriate symptoms, PFTs can serve as early diagnostic tools. In a classic report of 44 patients with dyspnea and normal chest radiographs but biopsy-proven DPLD, DlCO was decreased in 73%, VC was low in 57%, and TLC was low in 16% (20). Similarly, three patients with respiratory symptoms, open lung biopsy–confirmed DPLD, and a normal HRCT scan exhibited abnormal PFTs (mean FVC, 72.1% predicted; mean DlCO/alveolar volume, 72.2% predicted) (21). As such, appropriate symptoms in a patient with abnormal PFTs should prompt further evaluation for DPLD. Unfortunately, PFTs may be normal in the presence of histologic and radiographic evidence of DPLD (22, 23). For example, Risk and colleagues identified two patients with biopsy-proven IPF who had a DlCO > 70% predicted although rest and exercise P(a–a)O2 were abnormal (24). As such, although unusual, normal PFTs cannot be assumed to exclude IPF in the presence of suggestive clinical or radiographic abnormalities.

Many investigators have attempted to use PFTs in differentiating among DPLDs (2). Examples include the identification of a relative elevation of residual volume in hypersensitivity pneumonitis (25) compared with IPF, which is believed to be related to small airway involvement (2). In addition, differences in gas exchange have been confirmed by several groups, with IPF appearing to have a greater reduction in DlCO despite corrections for lung volume (14, 26). In fact, Risk and colleagues noted the greatest increases in P(a–a)O2 in those patients with UIP compared with desquamative interstitial pneumonia (24). Furthermore, this increase was predicted by a lower DlCO. Similar results were reported by Keogh and colleagues (15). Unfortunately, there is considerable overlap in these findings, which limits the practical clinical value of these differences.

Several groups have reported physiologic data in groups of patients with IIPs. Although comparative data are limited, the physiologic pattern seems quite similar as noted in Table 2. It is evident from a perusal of these data that significant overlap is present in physiologic testing, which limits their value in differential diagnosis of suspected DPLD.

TABLE 2.

PHYSIOLOGIC DATA FROM SELECTED SERIES OF PATIENTS WITH IDIOPATHIC INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA

| FVC | TLC | DlCO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | (% pred) | (% pred) | (% pred) |

| Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia | |||

| Nagai and colleagues (69) | 74 | — | 56 |

| Cottin and colleagues (70) | 59 | 61 | 52 |

| Bjoraker and colleagues (71) | 80 | 76 | 50 |

| Daniil and colleagues (72) | 73 | 72 | 44 |

| Fujita and colleagues (73) | 66 | — | — |

| Nicholson and colleagues (74) | 71 | — | 39 |

| Flaherty and colleagues (75) | 73* | 78* | 51* |

| 72† | 78† | 69† | |

| Riha and colleagues (76) | 63 | 92 | 39 |

| Kim and colleagues (77) | 66 | 72 | 51 |

| Ishii and colleagues (78) | 83 | — | — |

| Latsi and colleagues (43) | 73 | — | 42 |

| Flaherty and colleagues (62) | 71 | 82 | 48 |

| Jegal and colleagues (42) | 63* | 74* | 56* |

| 67† | 76† | 60† | |

| Usual Interstitial Pneumonia | |||

| Erbes and colleagues (13) | 89 | 79 | 46 |

| Nagai and colleagues (69) | 70 | — | 44 |

| Daniil and colleagues (72) | 74 | 66 | 44 |

| Bjoraker and colleagues (71) | 79 | 68 | 48 |

| Nicholson and colleagues (74) | 72 | — | 44 |

| Mogulkoc and colleagues (40) | 72 | 74 | 49 |

| Latsi and colleagues (43) | 72 | — | 47 |

| Collard and colleagues (63) | 71 | 78 | 52 |

| Flaherty and colleagues (62) | 68 | 72 | 50 |

| Jegal and colleagues (42) | 73 | 73 | 61 |

| Respiratory Bronchiolitis–associated Interstitial Lung Disease | |||

| Myers and colleagues (79) | 73 | 76 | 63 |

| Yousem and colleagues (80) | 83 | 102 | 62 |

| Moon and colleagues (81) | 91 | 89 | 57 |

| Nicholson and colleagues (74) | 63 | — | 35 |

| Ryu and colleagues (82) | 73 | — | 57 |

| Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia | |||

| Yousem and colleagues (80) | 68 | 94 | 45 |

| Ryu and colleagues (82) | 74 | — | 53 |

| Bronchiolitis Obliterans Organizing Pneumonia | |||

| Nagai and colleagues (69) | 74 | — | 58 |

Definition of abbreviations: DlCO = diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide; IIP = idiopathic interstitial pneumonia; NSIP = nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; TLC = total lung capacity.

Fibrotic NSIP.

Cellular NSIP.

Can Pulmonary Function Testing Establish Disease Severity?

Given the simplicity and widespread availability of pulmonary function testing, many investigators have examined the potential for simple physiologic measurements to stratify disease severity and to identify fibrosis and inflammation. Many of these studies were reported before concepts regarding classification of IIPs (1), complicating their interpretation. Gaensler and coworkers noted a “fair correlation” between histologic severity and physiologic indices (17). Crystal and colleagues reported “good” correlation between fibrosis and the coefficient of retraction and the change in exercise PaO2 and P(a–a)O2 but a “poor” correlation with spirometry, lung volumes, DlCO, and resting gas exchange in 18 patients with IPF (22). In a more detailed analysis, Fulmer and colleagues provided a semiquantitative histologic description of 23 patients with IPF (6). Almost all parameters of lung distensibility correlated with the extent of fibrosis, although not with cellularity. Although spirometry, lung volumes, and DlCO correlated poorly with histologic abnormality, exercise gas exchange (PaO2 and P[a–a]O2), corrected for achieved V̇o2, exhibited the best correlation with both histologic fibrosis and, to a lesser extent, cellularity. In 14 untreated patients with IPF, gas transfer and lung volumes correlated with the extent of fibrosis and cellular infiltration; both of these correlated more strongly than gas exchange with exercise (27). Cherniack and coworkers, using a more extensive semiquantitative histologic scoring system in 96 patients with IPF, noted no significant correlation between histologic fibrosis and any physiologic parameter (10). The DlCO correlated with “desquamation” of cells within the alveolar space. Importantly, significant differences were noted between morphologic–physiologic correlations in never-smokers and ever-smokers; significant correlations were noted between exercise gas exchange and histologic fibrosis only in never-smokers.

Among PFTs, DlCO correlates better with extent of disease on HRCT scans than do lung volumes or spirometry (28–30). In patients without concomitant emphysema, the extent of fibrotic disease on CT scan correlated with percent predicted DlCO, oxygenation desaturation with exercise, and the physiologic component of a clinical/radiologic/physiologic composite score (see below); spirometry and lung volumes were less helpful (31). Similar correlations have been reported by others (30, 32). Xaubet and coworkers described a moderate correlation between overall abnormality on HRCT scan in 39 untreated patients with IPF and DlCO as well as FVC (30). The extent of ground-glass opacity correlated with FVC and PaO2 with exercise. Brantly and colleagues noted a similar correlation between the extent of disease on HRCT scan and FVC (r = –0.66) and DlCO (r = –0.66) in 38 patients with pulmonary fibrosis associated with Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (32).

Watters and coworkers created a composite score of clinical (dyspnea), radiographic (chest radiograph), and physiologic parameters, the CRP score (33). The physiologic component of the CRP includes spirometric measures, lung volume (thoracic gas volume), DlCO corrected for alveolar volume, and resting and exercise PaO2 corrected for achieved V̇o2. The overall CRP score demonstrated better correlation with a semiquantitative histologic total pathology score. Wells and colleagues also confirmed a correlation between DlCO, exercise desaturation, and the physiologic component of the CRP score and the overall extent of fibrosis on HRCT scan in patients with IPF but without emphysema (28). A modified CRP scoring system has been created that incorporates additional clinical and radiologic findings while giving less weight to physiologic parameters (34). This modified CRP score correlated with the extent of fibrosis, cellularity, granulation/connective tissue, and total pathologic derangement. Another investigative group extended these observations by creating a composite score that included spirometric (FEV1 and FVC) and DlCO measurements (31). This composite physiologic index correlated better than individual parameters with the extent of disease on HRCT scan abnormality, which the authors thought likely reflected adjustment for concomitant emphysema. The use of such composite approaches in daily practice will require prospective validation.

As such, these data that suggest that the extent of fibrosis in IPF seems to correlate with the extent of desaturation during exercise testing while the reductions in TLC and FVC may relate to the extent of cellularity. These correlations appear to be particularly true in patients who have an absent smoking history. Unfortunately, the correlations are weak and definite clinical recommendations are difficult to establish.

Similar attempts have been made with other IIPs. Park and colleagues reported histologic and physiologic correlations in 21 patients with respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease (35). The severity of bronchial wall thickening was negatively correlated with FEV1, whereas the extent of ground-glass opacity correlated negatively with arterial oxygen saturation and the extent of centrilobular emphysema correlated negatively with FEV1/FVC. Patients with restrictive physiology (n = 8) exhibited a higher mean ground-glass opacity score than those with normal or obstructive physiology (n = 5). The obstructed patients had a higher mean emphysema score. The clinical significance of these results is unclear.

Can Pulmonary Function Testing Define Prognosis in IIPs?

Given its particularly ominous prognosis, numerous investigators have examined factors that may aid in predicting morbidity and mortality in IPF (2, 36). In general, reduced FVC and DlCO have been associated with reduced survival. This is exemplified by the study of 56 patients with IPF reported by Jezek and coworkers (23). These investigators noted impaired survival of those patients with (1) initial FVC < 60% predicted, (2) DlCO < 40% predicted, (3) mean pulmonary artery pressure above 30 mm Hg, or (4) an age at first symptoms over 40 yr. The importance of decreased FVC was also highlighted in a population-based cohort study of 244 cases of prevalent and incident IPF; for the incident cases higher percent predicted DlCO and FVC were associated with a better prognosis (37). Erbes and colleagues reported retrospective data in 99 patients with biopsy-proven IPF who were treated in a standard fashion with steroids; steroid nonresponders were subsequently treated with azathioprine (13). Decreased survival was noted in patients with a pretherapy TLC < 78% predicted and those with a TLC < 78% and VC < 83% predicted. A combined reduction in VC and TLC was associated with a 46% reduction in 5-yr survival. Interestingly, DlCO, PaO2 at rest, P(a–a)O2, and ΔPaO2 with exercise were not predictive of survival. In contrast, Raghu and coworkers noted increased mortality in those patients with DlCO < 30% predicted in a study of 54 patients prospectively enrolled in a trial of pirfenidone (38).

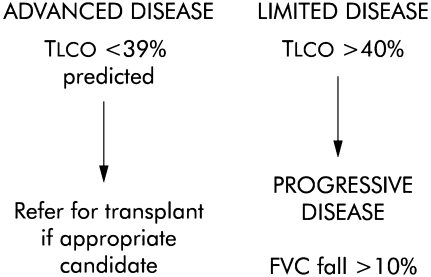

More recent studies have examined mortality prediction in patients whose diagnosis has been based on the latest international recommendations. A review of these studies has confirmed that pulmonary function studies have proven prognostic value in both IPF and NSIP (39). For example, several investigative groups have identified a baseline decrease in DlCO to be highly predictive of mortality in IPF and NSIP (40–42). Importantly, a low baseline DlCO seems to predict impaired survival, independent of histologic diagnosis (42, 43). On the basis of these results one group has proposed a simple stratification system characterizing patients with IPF and patients with NSIP as having advanced disease if the baseline DlCO is less than 39% predicted and limited if the DlCO is greater than 40% predicted (Figure 1) (39).

Figure 1.

Proposed classification of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) based on simple lung function criteria. DlCO = carbon monoxide diffusing capacity; FVC = forced vital capacity. Reprinted by permission from Reference 39.

Few investigators have directly compared the predictive ability of physiologic testing with HRCT scan estimation of disease activity. Gay and coworkers prospectively examined 38 patients with biopsy-proven DPLD (44). On using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, only semiquantitative estimates of HRCT scan and histologic fibrosis predicted survival. Importantly, no physiologic parameter was predictive nor did they add to the predictive ability of HRCT measurements. In an IPF patient population Mogulkoc and colleagues examined predictors of death in 115 patients (40). DlCO (less than 39% predicted) and a similar HRCT semiquantitative fibrotic score as in the work of Gay and coworkers proved predictive (see Figure 2). A model based on the combination of these two parameters optimized prediction of survival. In a more recent study semiquantitative assessment of HRCT scan and pulmonary function were evaluated in 315 patients with IPF enrolled in a placebo-controlled trial of IFN-γ-1b (41). A higher HRCT fibrotic score and lower DlCO were independently associated with mortality.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating curves for FVC % predicted (FVCPP), DlCO % predicted (DLCOPP), HRCT semiquantitative fibrotic score (HRCT-FS), and the combined model in 115 patients with IPF evaluated for lung transplantation. Reprinted by permission from Reference 40.

Given the correlation between exercise gas exchange and disease severity, several groups have examined the value of such measurement in predicting survival of patients with IPF. King and coworkers examined 238 patients with UIP, noting that PaO2 during cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) was predictive of survival, accounting for as much as 10.5% of the maximal score in the final model (45). One group noted that exercise-induced hypoxemia evaluated by ΔPaO2/ΔV̇o2 on CPET was strongly correlated with survival of 41 patients with IPF (46). Importantly, others have not confirmed that CPET measures of gas exchange provide additional prognostic value in patients with IPF (13, 44). Some investigators have examined the value of desaturation during a simpler, 6-min walk test in a retrospective study of 83 patients with IPF and 22 patients with NSIP (18). As noted earlier, 53% of patients with IPF and 36% of patients with NSIP experienced desaturation (trough saturation < 88% for at least 1 min). In multivariate modeling adjusting for demographic, static physiologic values, resting oxygenation, maximal distance walked, the extent of fibrotic abnormality on HRCT scan, and histopathologic findings, desaturation during timed walk testing was associated with significantly worse survival (hazard ratio, 4.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.58–12.64%). The 4-yr survival of patients with IPF who desaturated was 34.5% compared with those who did not desaturate (69.1%). In patients with NSIP who desaturated 4-yr survival was worse (65.6%) than among those who did not desaturate (100%; Figure 3A). A second group, studying a smaller number of patients with IPF, reached a similar conclusion (Figure 3B). More importantly, this group confirmed that the reproducibility of this measure of desaturation was good during serial measurement of a subgroup of 17 patients tested on two different occasions (K = 0.93). A third group has suggested that trough saturation in tertiles correlated with prognosis in patients with IPF (47). In summary, the available studies suggest that prognosis is poorer in those patients with decreased FVC, TLC, DlCO, and exertional desaturation.

Figure 3.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with IPF grouped by trough saturation during 6-min walk ⩽ 88% (dashed line) or > 88% (solid line). Reprinted by permission from Reference 18. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with IPF grouped by trough saturation to ⩽ 88% (solid circles) or > 88% (open circles) during a 6-min walk study. Reprinted by permission from Reference 67.

Can PFTs Aid in Monitoring Response to Therapy and Disease Progression?

Given their simplicity and widespread availability, PFTs are frequently used to determine disease progression and the response to therapy. Given the limited morphologic–physiologic correlations described earlier, and the need for simple, patient-friendly studies, most clinicians have relied on spirometry, lung volumes, DlCO, and measures of arterial oxygenation. To understand the threshold of change in these parameters that may be clinically significant, one need first appreciate the variability of these physiologic indices.

The American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society have provided detailed guidelines standardizing spirometric (48) and DlCO (49) measurement. The variability in FVC has been well defined among normal subjects (50) and patients with pulmonary disease (51). As such, Enright and colleagues were able to demonstrate that more than 90% of patients in a large pulmonary function laboratory were able to reproduce FVC within 5.3% (50). Longitudinal studies suggest that the change in FVC over time in normal subjects is approximately 11% but may be higher in patients with obstructive pulmonary disease (51). The variability for DlCO is likely higher (51). Data in patients with IPF are scarce, although Eaton and colleagues have provided insight while testing 30 patients 1 wk apart. As enumerated in Table 3, variability in FVC, TLC, and DlCO was less than with exercise measures. In a separate study, a subgroup of patients participating in a therapeutic trial underwent spirometric measurement during a mean duration of 3 wk (52); none of 81 patients with IPF had more than a 10% decrease in percentage of predicted FVC whereas only 1 patient had a 10% or greater increase in FVC. To date, most investigators have defined clinically significant changes in spirometry for patients with IPF as a change in FVC exceeding 10–15% (38, 53–59). In general, the DlCO change believed to be clinically significant has been greater than 20% (38, 53, 54, 56).

TABLE 3.

REPRODUCIBILITY OF PULMONARY FUNCTION MEASUREMENTS IN PATIENTS WITH IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY FIBROSIS

| Parameter | SDdiff between Two Measurements | SDdiff/Mean Value (%) |

|---|---|---|

| FVC, % pred | 6.45 | 7.9 |

| TLC, % pred | 4.71 | 5.5 |

| DlCO, % pred | 4.87 | 9.2 |

| 6 MWT distance | 17.9 | 4.2 |

| 6 MWT O2 desaturation | 2.5 | 28.3 |

| V̇o2max, % pred | 6.4 | 10.5 |

| O2 desaturation, adjusted for V̇o2max | 7.2 | 50.7 |

| CRP score | 6.5 | 25.9 |

| CPI | 3.5 | 7.8 |

Definition of abbreviations: 6 MWT = 6-min walk test; CPI = composite physiologic index; CRP = clinical, radiographic, pathologic score; SDdiff = standard deviation of the difference.

Adapted from Reference 67.

PFTs have been widely used in the serial evaluation of patients with IPF. Stack and coworkers noted improved survival of patients with IPF demonstrating an early improvement in FVC > 10% with corticosteroid therapy (58). Agusti and colleagues performed serial PFTs in 19 patients with IPF, noting a decrease in FVC, TLC, or DlCO by 1.5 yr in patients who continued to progress during the 3 yr of follow-up (60). van Oortegem and coworkers suggested that improvement in FVC or DlCO after 3 mo of therapy predicted stability or improvement during long-term follow-up (61). Hanson and coworkers, who examined 58 patients with IPF who survived at least 1 yr from the initiation of therapy, noted that survival was better among patients with improved or unchanged FVC at 1 yr compared with patients exhibiting a 10% or greater reduction in FVC serial spirometry (54). Survival was worse among patients experiencing a decline in DlCO of 20% or more after 1 yr of therapy. The concordance between both of these studies was good; no patient with improved FVC had a fall in DlCO. Furthermore, measurement of resting or exercise oxygenation provided no incremental value.

Several groups have confirmed the prognostic value of serial physiologic studies in groups of patients with DPLD characterized on the basis of the latest guidelines. In this way serial change in spirometry (42, 43, 52, 62, 63), arterial blood gases (63), and DlCO (63) in patients with NSIP (42, 43, 62) and UIP (42, 62) has been examined. These investigators confirm impaired survival with the documentation of 6- and 12-mo worsening in these physiologic studies; this prognostic ability persisted after accounting for baseline severity of disease and adjusting for other variables that influence survival. A decrease of 10% in FVC seems to be the most predictive, although the operating characteristics of this parameter are modest, at best. In the placebo-treated arm of a large therapeutic trial in IPF, where 25 of 163 patients died, a decrease in FVC exceeding 10% predicted exhibited a sensitivity of 60%, a specificity of 75%, a positive predictive value of 31%, and a negative predictive value of 91% (52). This, in part, relates to the occurrence of rapid deterioration and death that may occur in patients with IPF (64, 65).

The CRP score represents a potentially more accurate modality for assessing response to therapy in IPF. Response is defined as a 10-point drop in CRP, stability is defined as a less than 10-point change, and nonresponse is defined as a 10-point rise in CRP (33). Limited early data provided short-term validation for this scoring system (33, 66), although subsequent longitudinal, short-term study suggests significant variability (Table 3) (67). Interestingly, a randomized therapeutic trial suggested differences in longitudinal measures of FVC and DlCO but not in CRP scores (68). Gay and colleagues demonstrated that response, as defined by CRP scoring, during 3 mo of steroid therapy in IPF was associated with improved long-term survival (44). Another investigative group has attempted to improve predictive ability by creating a simple, composite physiologic index that includes the FVC, FEV1, and DlCO, accounting for the extent of emphysema on HRCT scan; this composite physiologic index correlated well with the extent of fibrotic abnormality on CT scan (31). The variability of this parameter appears to be less during short-term serial testing (Table 3) (67).

CONCLUSIONS

Pulmonary function studies are simple, widely available, and frequently used in the evaluation and management of patients with DPLDs, particularly IPF and NSIP. Review of available data suggests the following:

PFTs can aid in the diagnosis of DPLD, although the pattern of abnormality is nonspecific.

PFTs provide a rough estimate of histologic severity but do not provide definitive quantification of histologic fibrosis or inflammation.

Baseline PFTs may provide an estimate of prognosis.

Serial PFTs provide valuable information in determining disease progression and response to therapy.

FVC and DlCO are the most valuable serial measurements, although further data are required to examine longitudinal change in exercise gas exchange.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) NHLBI grant 5 P50 HL56402, NIH/NHLBI NO1-HR-46162, NHLBI U10 HL080371, NIH/NHLBI R01 HL073728, and NHLBI 2K24HL04212 and 1 K23 HL68713.

Conflict of Interest Statement: Neither of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:277–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Donnell D. Physiology of interstitial lung disease. In: Schwarz M, King T Jr, editors. Interstitial lung disease. Hamilton, ON, Canada: Marcel Dekker; 1998. pp. 51–70.

- 3.Schlueter D, Immekus J, Stead W. Relationship between maximal inspiratory pressure and total lung capacity (coefficient of retraction) in normal subjects and in patients with emphysema, asthma, and diffuse pulmonary infiltration. Am Rev Respir Dis 1967;96:656–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macklem P, Becklake M. The relationship between mechanical and diffusing properties of the lung in health and disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1963;87:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson G, Pride N, Davis J, Schroter R. Exponential description of the static pressure–volume curve of normal and diseased lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 1979;120:799–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulmer J, Roberts W, von Gael E, Crystal R. Morphologic–physiologic correlates of the severity of fibrosis and degree of cellularity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 1979;63:65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottlieb D, Snider G. Lung function in pulmonary fibrosis. In: Phan S, Thrall R, editors. Lung biology in health and disease: pulmonary fibrosis. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1995. pp. 85–135.

- 8.Nava S, Rubini F. Lung and chest wall mechanics in ventilated patients with end stage idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 1999;54:390–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yernault J-C, deJonghe M, de Coster A, Englert M. Pulmonary mechanics in diffuse fibrosing alveolitis. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir 1975;11:231–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherniack RM, Colby TV, Flint A, Thurlbeck WM, Waldron JA, Ackerson L, Schwarz MI, King TE. Correlation of structure and function in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:1180–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doherty M, Pearson M, O'Grady E, Pellegrini V, Calverley P. Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis with preserved lung volumes. Thorax 1997;52:998–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cottin V, Nunes H, Brillet P, Delaval P, Devouassoux G, Tillie-Leblond I, Israel-Biet D, Court-Fortune I, Valeyre D, Cordier J; Groupe d'Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies “Orphelines” Pulmonaires. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a distinct underrecognised entity. Eur Respir J 2005;26:586–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erbes R, Schaberg T, Loddenkemper R. Lung function tests in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: are they helpful for predicting outcome? Chest 1997;111:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn T, Watters L, Hendrix C, Cherniack R, Schwarz M, King T. Gas exchange at a given degree of volume restriction is different in sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Med 1988;85:221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keogh B, Lakatos E, Price D, Crystal R. Importance of the lower respiratory tract in oxygen transfer: exercise testing in patients with interstitial and destructive lung diseases. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984;129:S76–S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson H. Clinical application of pulmonary function and exercise tests in the management of patients with interstitial lung disease. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 1994;15:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaensler E, Carrington C, Coutu R, Fitzgerald M. Radiographic–physiologic–pathologic correlations in interstitial pneumonias. Prog Respir Res 1975;8:223–241. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lama V, Flaherty K, Toews G, Colby T, Travis W, Long Q, Murray S, Kazerooni E, Gross B, Lynch J III, et al. Prognostic value of desaturation during a 6-minute walk test in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:1084–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds H. Diagnostic and management strategies for diffuse interstitial lung disease. Chest 1998;113:192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epler G, McLoud T, Gaensler E, Mikus J, Carrington C. Normal chest roentgenograms in chronic diffuse infiltrative lung disease. N Engl J Med 1978;298:934–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orens J, Kazerooni E, Martinez F, Curtis J, Gross B, Flint A, Lynch J III. The sensitivity of high-resolution CT in detecting idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis proved by open lung biopsy: a prospective study. Chest 1995;108:109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crystal R, Fulmer J, Roberts W, Moss M, Line B, Reynolds H. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical, histologic, radiographic, physiologic, scintigraphic, cytologic, and biochemical aspects. Ann Intern Med 1976;85:769–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jezek V, Fucik J, Michaljanic A, Jeskova L. The prognostic significance of functional tests in cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir 1980;16:711–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Risk C, Epler G, Gaensler E. Exercise alveolar–arterial oxygen pressure difference in interstitial lung disease. Chest 1984;85:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.William J. Pulmonary function in patients with farmer's lung. Thorax 1963;18:255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agusti A, Roca J, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Xaubet A, Agusti-Vidal A. Different patterns of gas exchange response to exercise in asbestosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 1988;1:510–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chinet T, Jaubert F, Dusser D, Danel C, Chretien J, Huchon G. Effects of inflammation and fibrosis on pulmonary function in diffuse lung fibrosis. Thorax 1990;45:675–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells A, King A, Rubens M, Cramer D, du Bois R, Hansell D. Lone cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis: a functional–morphologic correlation based on extent of disease on thin-section computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:1367–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wells A, Hansell D, Rubens M, King A, Cramer D, Black C, du Bois RM. Fibrosing alveolitis in systemic sclerosis. Indices of lung function in relation to extent of disease on computed tomography. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1229–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xaubet A, Agusti C, Luburich P, Roca J, Monton C, Ayuso M, Barbera J, Rodriguez-Roisin R. Pulmonary function tests and CT scan in the management of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wells A, Desai S, Rubens M, Goh N, Cramer D, Nicholson A, Colby T, du Bois R, Hansell D. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a composite physiologic index derived from disease extent observed by computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:962–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brantly M, Avila N, Shotelersuk V, Lucero C, Huizing M, Gahl W. Pulmonary function and high-resolution CT findings in patients with an inherited form of pulmonary fibrosis, Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome, due to mutations in HPS-1. Chest 2000;117:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watters L, King T, Schwarz M, Waldron J, Stanford R. A clinical, radiographic, and physiologic scoring system for the longitudinal assessment of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986;133:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King T Jr, Schwarz M, Brown K, Tooze J, Colby T, Waldron J Jr, Flint A, Thurlbec W, Cherniack R. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: relationship between histopathologic features and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:1025–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park J, Brown K, Tuder R, Hale V, King T Jr, Lynch D. Respiratory bronchiolitis–associated interstitial lung disease: radiologic features with clinical and pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2002;26:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lama V, Martinez F. Resting and exercise physiology in interstitial lung diseases. Clin Chest Med 2004;25:435–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hubbard R, Johnston I, Britton J. Survival in patients with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis: a population-based cohort study. Chest 1998;113:396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raghu G, Johnson W, Lockhart D, Mageto Y. Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with a new antifibrotic agent, pirfenidone: results of a prospective, open-label phase II study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egan J, Martinez F, Wells A, Williams T. Lung function estimates in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the potential for a simple classification. Thorax 2005;60:270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mogulkoc N, Brutsche M, Bishop P, Greaves S, Horrocks A, Egan J. Pulmonary function in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and referral for lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lynch D, Godwin J, Safrin S, Starko K, Hormel P, Brown K, Raghu G, King T Jr, Bradford W, Schwartz D, et al.; Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Study Group. High-resolution computed tomography in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and prognosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jegal U, Kim D, Shim T, Lim C, Lee S, Koh Y, Kim W, Kim W, Lee J, Travis W, et al. Physiology is a stronger predictor of survival than pathology in fibrotic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:639–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latsi PI, du Bois RM, Nicholson AG, Colby TV, Bisirtzoglou D, Nikolakopoulou A, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Wells AU. Fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: the prognostic value of longitudinal functional trends. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:531–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gay S, Kazerooni E, Toews G, Lynch J III, Gross B, Cascade P, Spizarny D, Flint A, Schork M, Whyte R, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: predicting response to therapy and survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1063–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.King T Jr, Tooze J, Schwarz M, Brown K, Cherniack R. Predicting survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: scoring system and survival model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:1171–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miki K, Maekura R, Hiraga T, Okuda Y, Okamato T, Hirotani A, Ogura T. Impairments and prognostic factors for survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med 2003;97:482–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hallstrand T, Boitano L, Johnson W, Spada C, Hayes J, Raghu G. The timed walk test as a measure of severity and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2005;25:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller M, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten C, Gustafsson P, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacIntyre N, Crapo R, Viegi G, Johnson D, van der Grinten C, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Enright P, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 2005;26:720–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Enright P, Beck K, Sherrill D. Repeatability of spirometry in 18,000 adult patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo R, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, van der Grinten C, Gustafsson P, Hankinson J, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005;26:948–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.King T Jr, Safrin S, Starko K, Brown K, Noble P, Raghu G, Schwartz D. Analyses of efficacy end points in a controlled trial of interferon-γ1b for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2005;127:171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Douglas W, Ryu J, Swensen S, Offord K, Shroeder D, Caron G, DeRemee R. Colchicine versus prednisone in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a randomized prospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanson D, Winterbauer R, Kirtland S, Wu R. Changes in pulmonary function test results after 1 year of therapy as predictors of survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 1995;108:305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson M, Kwan S, Snell N, Nunn A, Darbyshire J, Turner-Warwick M. Randomized controlled trial comparing prednisolone alone with cyclophosphamide and low dose prednisolone in combination in cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Thorax 1989;44:280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raghu G, Depaso W, Cain K, Hammar S, Wetzel C, Dreis D, Hutchinson J, Pardee N, Winterbauer R. Azathioprine combined with prednisone in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a prospective double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;144:291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rudd R, Haslam P, Turner-Warwick M. Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis: relationships of pulmonary physiology and bronchoalveolar lavage to response to treatment and prognosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1981;124:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stack B, Choo-Kang Y, Heard B. The prognosis of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Thorax 1972;27:535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turner-Warwick M, Burrows B, Johnson A. Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis: response to corticosteroid therapy and its effect on survival. Thorax 1980;35:593–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Agusti C, Xaubet A, Agusti A, Roca J, Ramirez J, Rodriguez-Roisin R. Clinical and functional assessment of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: results of a 3 year follow-up. Eur Respir J 1994;7:643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Oortegem K, Wallaert B, Marquette C, Ramon P, Perez T, Lafitte J, Tonnel A. Determinants of response to immunosuppressive therapy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 1994;7:1950–1957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flaherty K, Mumford J, Murray S, Kazerooni E, Gross B, Colby T, Travis W, Flint A, Toews G, Lynch J, et al. Prognostic implications of physiologic and radiographic changes in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Collard H, King T, Bartelson B, Vourlekis J, Schwarz M, Brown K. Changes in clinical and physiologic variables predict survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:538–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martinez F, Safrin S, Weycker D, Starko K, Bradford W, King T Jr, Flaherty K, Schwartz D, Noble P, Raghu G, et al.; IPF Study Group. The clinical course of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:963–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim D, Park J, Park B, Lee J, Nicholson A, Colby T. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: frequency and clinical features. Eur Respir J 2006;27:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watters L, Schwarz M, Cherniack R, Waldron J, Dunn T, Stanford R, King T. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: pretreatment bronchoalveolar lavage cellular constituents and their relationships with lung histopathology and clinical response to therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;135:696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eaton T, Young PR, Milne D, Wells A. Six-minute walk, maximal exercise tests: reproducibility in fibrotic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:1150–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Demedts M, Behr J, Buhl R, Costabel U, Dekhuijzen R, Jansen H, MacNee W, Thorneer M, Wallaert B, Laurent F, et al.; IFIGENIA Study Group. High-dose acetylcysteine in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2229–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nagai S, Kitaichi M, Itoh H, Nishimura K, Colby T. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia/fibrosis: comparison with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and BOOP. Eur Respir J 1998;12:1010–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cottin V, Donsbeck A, Revel D, Loire R, Cordier J. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: individualization of a clinicopathologic entity in a series of 12 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:1286–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bjoraker J, Ryu J, Edwin M, Myers J, Tazelaar H, Schoreder D, Offord K. Prognostic significance of histopathologic subsets in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Daniil Z, Gilchrist F, Nicholson A, Hansell D, Harris J, Colby T, duBois R. A histologic pattern of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is associated with a better prognosis than usual interstitial pneumonia in patients with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fujita J, Yamadori I, Bandoh S, Mizobuchi K, Suemitsu I, Nakamura Y, Ohtsuki Y, Takahara J. Clinical features of three fatal cases of non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Intern Med 2000;39:407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nicholson A, Colby T, DuBois R, Hansell D, Wells A. The prognostic significance of the histologic pattern of interstitial pneumonia in patients presenting with the clinical entity of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:2213–2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Flaherty K, Toews G, Travis W, Colby T, Kazerooni E, Gross B, Jain A, Strawderman R III, Paine R, Flint A, et al. Clinical significance of histological classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2002;19:275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Riha R, Duhig E, Clarke B, Steele R, Slaughter R, Zimmerman P. Survival of patients with biopsy-proven usual interstitial pneumonia and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2002;19:1114–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim E, Lee K, Johkoh T, Kim T, Suh G, Kwon O, Han J. Interstitial lung diseases associated with collagen vascular diseases: radiologic and histopathologic findings. Radiographics 2002;22:S151–S165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ishii H, Mukae H, Kadota J, Kaida H, Nagata T, Abe K, Matsukura S, Kohno S. High serum concentrations of surfactant protein A in usual interstitial pneumonia compared with non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Thorax 2003;58:52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Myers J, Veal C, Shin M, Katzenstein A. Respiratory bronchiolitis causing interstitial lung disease: a clinicopathologic study of six cases. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;135:880–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yousem S, Colby T, Gaensler E. Respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease and its relationship to desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Mayo Clin Proc 1989;64:1373–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moon J, du Bois R, Colby T, Hansell DM, Nicholson AG. Clinical significance of respiratory bronchiolitis on open lung biopsy and its relationship to smoking related interstitial lung disease. Thorax 1999;54:1009–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ryu J, Myers J, Capizzi S, Douglas W, Vassallo R, Decker P. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia and respiratory bronchiolitis–associated interstitial lung disease. Chest 2005;127:178–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]