Abstract

We reported previously that urinary angiotensinogen (UAGT) levels provide a specific index of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system (RAS) status in angiotensin II– dependent hypertensive rats. To study this system in humans, we recently developed a human angiotensinogen ELISA. To test the hypothesis that UAGT is increased in hypertensive patients, we recruited 110 adults. Four subjects with estimated glomerular filtration levels <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 were excluded because previous studies have already shown that UAGT is highly correlated with estimated glomerular filtration in this stage of chronic kidney disease. Consequently, 106 paired samples of urine and plasma were analyzed from 70 hypertensive patients (39 treated with RAS blockers [angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers; systolic blood pressure: 139±3 mm Hg] and 31 not treated with RAS blockers [systolic blood pressure: 151±4 mm Hg]) and 36 normotensive subjects (systolic blood pressure: 122±2 mm Hg). UAGT, normalized by urinary concentrations of creatinine, were not correlated with race, gender, age, height, body weight, body mass index, fractional excretion of sodium, plasma angiotensinogen levels, or estimated glomerular filtration. However, UAGT/urinary concentration of creatinine was significantly positively correlated with systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (r=0.5994), and urinary protein:creatinine ratio (r=0.4597). UAGT/urinary concentration of creatinine was significantly greater in hypertensive patients not treated with RAS blockers (25.00±4.96 μg/g) compared with normotensive subjects (13.70±2.33 μg/g). Importantly, patients treated with RAS blockers exhibited a marked attenuation of this augmentation (13.26±2.60 μg/g). These data indicate that UAGT is increased in hypertensive patients, and treatment with RAS blockers suppresses UAGT, suggesting that the efficacy of RAS blockade to reduce the intrarenal RAS activity can be assessed by measurements of UAGT.

Keywords: angiotensinogen, ELISA, renin-angiotensin system, hypertension, clinical study, urine

Uncontrolled hypertension induces structural and functional alterations in the kidney, which can eventually lead to end-stage renal disease.1 Effective control of blood pressure retards the progression of renal failure and reduces the morbidity and mortality rates associated with hypertensive vascular disease.2–4 Recent findings related to the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), which is one of the most important mechanisms for blood pressure regulation and electrolyte homeostasis, have provided an improved understanding of the pathophysiology of hypertension.5,6 In recent years, the focus of interest on the RAS has shifted to a main emphasis on the role of the local/tissue RAS in specific tissues.7 Emerging evidence has demonstrated the importance of the tissue RAS in the brain,8 heart,9 adrenal glands,10 and vasculature,11,12 as well as the kidneys.5,6 There is substantial evidence that the major fraction of angiotensin II present in renal tissues is generated locally from angiotensinogen (AGT) delivered to the kidney, as well as from AGT locally produced by proximal tubule cells.13 Renin secreted by the juxtaglomerular apparatus cells into the renal interstitium and vascular compartment also provides a pathway for the local generation of angiotensin I.14 Angiotensin-converting enzyme is abundant in the kidney and is present in proximal tubules, distal tubules, and collecting ducts.15 Angiotensin I delivered to the kidney can also be converted to angiotensin II.16 Therefore, all of the components necessary to generate intrarenal angiotensin II are present along the nephron.5,6

AGT is the only known substrate for renin, the rate-limiting enzyme of the RAS. Because the level of AGT is close to the Michaelis-Menten constant for renin, not only renin levels but also AGT levels can control the activity of the RAS, and upregulation of AGT levels may lead to elevated angiotensin peptide levels and increases in blood pressure.17,18 Recent studies on experimental animal models and transgenic mice have documented the involvement of AGT in the activation of the RAS and the development of hypertension.19–27 Genetic manipulations that lead to overexpression of AGT have consistently been shown to cause hypertension.28,29 In human genetic studies, a linkage has been established between the AGT gene and hypertension.30–33 Thus, AGT plays an important role in blood pressure regulation.

Recently, we reported that urinary excretion rates of AGT provide a specific index of intrarenal RAS status in angiotensin II–dependent hypertensive rats.34–38 In addition, we recently developed a direct quantitative method to measure urinary AGT using human AGT ELISA.39 These data prompted us to measure urinary AGT in hypertensive patients and to investigate correlations with clinical parameters. Therefore, this study was performed to test the hypothesis that urinary AGT levels are enhanced in hypertensive patients and correlated with some clinical parameters.

Methods

Study Design and Sample Collections

The experimental protocol of this study was approved by the institutional review board and by the clinical and translational research center at Tulane University. A total of 110 subjects were recruited in Tulane University Health Sciences Center and associated clinics, and all of the samples were obtained with written informed consent. Four subjects with estimated glomerular filtration rates <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 were excluded, because previous studies have already shown that urinary angiotensinogen (UAGT)/urinary concentration of creatinine (UCre) levels are highly correlated with estimated glomerular filtration rate in this stage of chronic kidney disease.40,41 Consequently, 106 paired samples of urine and plasma were analyzed from 70 hypertensive patients (39 treated with RAS blockers [angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors {n=30} or angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers {n=9}] and 31 not treated with RAS blockers) and 36 normotensive subjects. A random spot urine sample and a blood sample were obtained from participants at clinic visit. Height, body weight, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure were also recorded on the same day.

Measurements

Serum concentrations of sodium, potassium, and creatinine and urinary concentrations of sodium, potassium, and protein were measured in the clinical laboratory in the Tulane University Health Sciences Center. Urinary concentrations of albumin and creatinine were measured with a DCA 2000 Analyzer (Bayer). Plasma concentrations and urinary concentrations of AGT were measured with human AGT ELISA kits, as described previously.39 The estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Formula (175×standardized serum creatinine−1.154×age−0.203×0.742 [if the individual is female]×1.212 [if the individual is black]×0.741 [if the individual is Asian]),42 which was found to correlate well with glomerular filtration rate corrected for body surface area in adults.43

Statistical Analyses

Pearson single-regression analyses and Spearman single-regression analyses were used for parametric data and nonparametric data, respectively. Standard least-squares method was used for multiple regression analysis. One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s test were used to compare group means. All of the data are presented as means±SEs. P<0.05 was considered significant. All of the computations, including data management and statistical analyses, were performed with JMP software (SAS Institute).

Results

Subjects Profiles and Laboratory Data

The flow chart of the grouping of the participants in this study is illustrated in Figure S1 (in the online data supplement available at http://hyper.ahajournals.org). The demographics and baseline laboratory data of the included subjects are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Subject Profiles

| Parameters | Normotensive (N=36) | HTN–RASB (N=31) | HTN+RASB (N=39) | P Value | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race, A/B/O | 2/12/22 | 11/14/6 | 0/30/9 | <0.0001 | 37.75 |

| Gender, F/M | 26/10 | 17/14 | 28/11 | 0.2320 | 2.92 |

| Age, y | 47.22±1.99 | 47.42±2.08 | 53.97±1.57*† | 0.0140 | |

| Height, cm | 168.29±1.61 | 167.34±1.74 | 168.24±1.43 | 0.8998 | |

| BW, kg | 76.28±2.74 | 82.29±4.54 | 101.75±3.94*† | <0.0001 | |

| BMI | 26.93±0.90 | 29.30±1.52 | 35.88±1.28*† | <0.0001 | |

| SBP, mm Hg | 122.39±2.10 | 151.16±3.59* | 139.46±2.95*† | < 0.0001 | |

| DBP, mm Hg | 72.00±1.59 | 86.29±1.89* | 78.15±1.28*† | < 0.0001 |

A indicates Asian; B, black; O, Others (white and Hispanic); F, female; M, male; BW, body weight; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HTN, hypertensive patients; RASB, renin-angiotensin system blockade.

P<0.05 vs normotensive.

P<0.05 vs HTN–RASB.

Table 2.

Laboratory Data

| Parameters | Normotensive (N=36) | HTN–RASB (N=31) | HTN+RASB (N=39) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Na, mEq/L | 138.75±0.38 | 139.58±0.57 | 137.56±0.43† | 0.0096 |

| Serum K, mEq/L | 4.21±0.04 | 4.01±0.07 | 4.22±0.08 | 0.0570 |

| Serum Cre, mg/dL | 0.78±0.03 | 0.96±0.04* | 1.04±0.06* | 0.0005 |

| Plasma AGT, μg/mL | 31.91±3.02 | 26.51±1.24 | 27.60±1.44 | 0.1654 |

| UNa/UCre, mEq/g | 121.28±21.69 | 111.78±18.18 | 57.91±7.18*† | 0.0122 |

| UK/UCre, mEq/g | 50.58±6.40 | 32.22±5.49* | 26.20±2.83* | 0.0013 |

| UPro/UCre, g/g | 0.09±0.02 | 0.47±0.14* | 0.09±0.01† | 0.0005 |

| UAlb/UCre, mg/g | 22.74±9.75 | 131.57±30.79* | 28.95±7.18† | <0.0001 |

| FENa, % | 0.65±0.11 | 0.73±0.10 | 0.41±0.05† | 0.0327 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 94.95±3.36 | 75.63±4.32* | 79.58±4.99* | 0.0057 |

Cre indicates creatinine; UNa/UCre, urinary sodium:creatinine ratio; UK/UCre, urinary potassium: creatinine ratio; UPro/UCre, urinary protein:creatinine ratio; UAlb/UCre, urinary albumin:creatinine ratio; FENa, fractional excretion of sodium; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HTN, hypertensive patients; RASB, renin-angiotensin system blockade.

P<0.05 vs normotensive.

P<0.05 vs HTN–RASB.

Single-Regression Analyses

Figure 1 demonstrates single-regression analyses for urinary AGT:creatinine ratio (UAGT/UCre) with clinical parameters. UAGT/UCre levels are not correlated with race, gender, age, height, body weight, body mass index, serum sodium levels, serum potassium levels, serum creatinine levels, urinary sodium:creatinine ratio, urinary potassium:creatinine ratio, fractional excretion of sodium, plasma AGT levels (r=0.0172; P=0.8589), or estimated glomerular filtration rate (r=0.1230; P=0.2092). However, UAGT/UCre levels are significantly positively correlated with systolic blood pressure (Figure 1A; r=0.1985; P=0.0385), diastolic blood pressure (Figure 1B; r=0.2475; P=0.0105), urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (Figure 1C; r=0.5994; P<0.0001), and urinary protein: creatinine ratio (Figure 1D: r=0.4597: P<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Single regression analyses for UAGT/UCre levels with systolic blood pressure (A), diastolic blood pressure (B), urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (C), and urinary protein:creatinine ratio (D), respectively.

Multiple-Regression Analyses

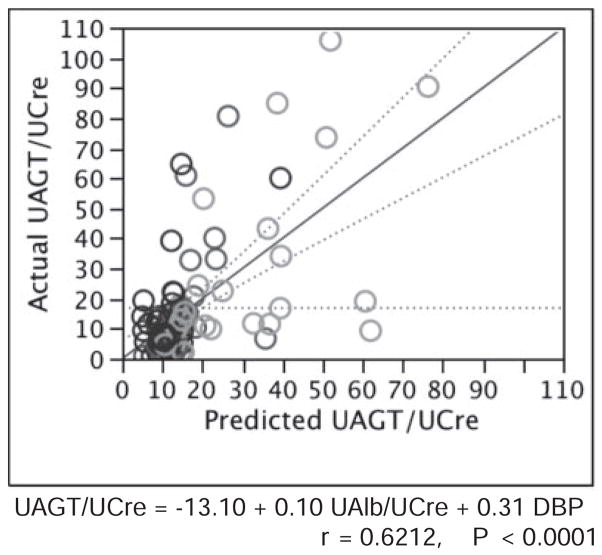

Factors with significant single correlation with UAGT/UCre levels were adopted as explanatory variables in multiple-regression analysis. To reduce the impact of multicollinearity, we selected explanatory variables so that the mean sum of squares for the residual would be minimal in multiple-regression analysis. As a result, systolic blood pressure and urinary protein:creatinine ratio were excluded, as described in Table 3. Using the remaining 2 parameters, multiple-regression analysis was re-evaluated. As described in Figure 2, only 2 parameters can account for ≈40% of variation of UAGT/UCre levels (r=0.6212; R2=0.3859; P<0.0001).

Table 3.

Multiple-Regression Analysis by Stepwise Method for UAGT/UCre

| Parameters | Estimate | SE | T Ratio | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −9.19 | 12.43 | −0.74 | 0.4615 |

| UAlb/UCre, mg/g | 0.10 | 0.02 | 5.07 | < 0.0001* |

| DBP, mm Hg | 0.37 | 0.19 | 1.91 | 0.0489* |

| SBP, mm Hg | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.66 | 0.5117 |

| UPro/UCre, g/g | 2.45 | 4.71 | 0.52 | 0.6044 |

UAlb/UCre indicates urinary albumin:creatinine ratio; UPro/UCre, urinary protein:creatinine ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

P<0.05.

Figure 2.

Multiple-regression analysis for UAGT/UCre levels.

Urinary AGT Levels in Hypertensive Patients

Figure 3 exhibits UAGT/UCre levels in hypertensive patients with/without RAS blockade and in normotensive subjects. UAGT/UCre levels were significantly greater in hypertensive patients without RAS blockade (25.00±4.96 μg/g) compared with normotensive subjects (13.70±2.33; P=0.0208). Importantly, the usage of RAS blockade prevented the augmentation (13.26±2.60; P=0.0147) observed in hypertensive patients without RAS blockade.

Figure 3.

UAGT/UCre levels in hypertensive patients (HTN) with/without renin-angiotensin system blockade (RASB) and in normotensive subjects. *P<0.05 vs normotensive; †P<0.05 vs HTN–RASB.

Discussion

Grouping

In this study, we randomly recruited female and male subjects between the ages of 18 and 80 years from all races without any bias in the selection process. Accordingly, there were some deviations in the grouping of race, age, body weight, and body mass index (Table 1). However, it is very important to emphasize here that all of these parameters (race, age, body weight, and body mass index) were not correlated with UAGT/UCre levels, as described above. Therefore, it seems unlikely that these deviations affected the final results reported herein.

Origin of Urinary AGT

Although most of the circulating AGT is produced and secreted by the liver, the kidneys also produce AGT.6 Intrarenal AGT mRNA and protein have been localized to proximal tubule cells, indicating that the intratubular angiotensin II could be derived from locally formed and secreted AGT.44,45 The AGT produced in proximal tubule cells appears to be secreted directly into the tubular lumen in addition to producing its metabolites intracellularly and secreting them into the tubular lumen.46 Proximal tubular AGT concentrations in anesthetized rats have been reported in the range of 300 to 600 nmol/L, which greatly exceeded the free angiotensin I and angiotensin II tubular fluid concentrations.5 Because of its molecular size (≈50 – 60 kDa), little plasma AGT is expected to filter across the glomerular membrane, further supporting the concept that proximal tubular cells secrete AGT directly into the tubules.47 To determine whether circulating AGT is a source of urinary AGT, human AGT was infused into hypertensive and normotensive rats, and it was found that circulating human AGT was not detectable in the urine.37 The failure to detect human AGT in the urine indicates limited glomerular permeability and/or tubular degradation. These findings support the hypothesis that urinary AGT comes from the AGT that is formed and secreted by the proximal tubules and not from plasma.

In agreement with this concept, plasma AGT levels were not correlated with UAGT/UCre levels in this study. Moreover, plasma AGT levels were not different among the 3 groups, although UAGT/UCre levels were significantly different among the 3 groups in this study. Therefore, it seems highly likely that AGT in urine originates from AGT in the kidney and not from AGT in plasma.

Enhanced Urinary AGT in Hypertensive Patients Is not a Nonspecific Consequence of Proteinuria

As described previously, we reported that urinary excretion rates of AGT provide a specific index of intrarenal RAS status in angiotensin II–dependent hypertensive rats.34–38 To determine whether the increase in urinary AGT excretion was simply a nonspecific consequence of the proteinuria and hypertension, additional studies were performed in rats made hypertensive with deoxycorticosterone acetate salt plus a high-salt diet.37 Although urinary protein excretion in deoxycorticosterone acetate salt–induced volume-dependent hypertensive rats was increased to the same or greater extent, urinary AGT was significantly lower in volume-dependent hypertensive rats than in angiotensin II–dependent hypertensive rats and was not greater than in control rats.37

Similar observations were obtained in a previous study in chronic kidney disease patients.41 UAGT/UCre levels in diabetic nephropathy patients (795.67±296.03 μg/g) and in membranous nephropathy (503.53±297.68 μg/g) were much higher than the average in chronic kidney disease patients (273.17±62.22 μg/g).41 Importantly, an activated intrarenal RAS has been reported in the progression of renal injury in diabetic nephropathy,48,49 as well as in membranous nephropathy,50 in human subjects. In contrast, UAGT/UCre levels in minimal change (8.28±3.70 μg/g) were similar with that in control subjects (10.78±3.42 μg/g), although patients with minimal change showed severe proteinuria.41 These findings in hypertensive animals, as well as in chronic kidney disease patients, support the hypothesis that the enhanced urinary AGT in hypertensive patients in this study is not a nonspecific consequence of proteinuria.

In the present study, UAGT/UCre levels were significantly positively correlated with urinary albumin:creatinine ratio and urinary protein:creatinine ratio. Therefore, in many cases, subjects who showed high UAGT/UCre levels also showed high urinary albumin:creatinine ratio and/or high urinary protein:creatinine ratio. However, when individual values were examined, there were also cases where UAGT/UCre levels did not parallel urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (Figure 1C) and/or high urinary protein:creatinine ratio (Figure 1D). Also, preliminary data indicate that increased urinary AGT levels are precedent to increased urinary albumin levels and urinary protein levels in type 1 diabetic juvenile subjects (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that the enhanced urinary AGT in hypertensive patients in this study is not just a nonspecific consequence of proteinuria.

Urinary AGT Levels Are More Closely Correlated With Diastolic Blood Pressure Than With Systolic Blood Pressure

The Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group demonstrated that the major predictor of diastolic blood pressure is the total peripheral vascular resistance determined by the compliance of blood vessels, as well as blood viscosity.51 In addition, it is well established that isolated diastolic hypertension is observed in younger adults, especially in the early stage of hypertension, and reflects the increase in vascular resistance from arteriola to arteriole without sclerotic changes in major arteries.52 In the present study, the population of hypertensive patients consists predominantly of younger adults with a median age of 50 years. In addition, an exclusion criterion of estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 was applied in the present study. Therefore, it seems likely that the hypertensive patients involved in the present study represent an early stage of hypertension with preserved renal function as evident by a normal range of serum creatinine, urinary protein:creatinine ratio, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (Table 2). This may account for the reason why UAGT/UCre levels were more significantly correlated with diastolic blood pressure than with systolic blood pressure. Prospective studies involving patients in every stage of hypertension will qualify this issue.

Other Modulating Factors on Urinary AGT Levels

Hypertensive patients treated with RAS blockers had higher body mass index (Table 1) and lower urinary sodium excretion (Table 2), thereby suggesting a possible state of insulin resistance. Thus, it is possible that urinary AGT levels are influenced by the difference in insulin sensitivity, in addition to the usage of RAS blockers. It is reported that insulin sensitivity modulates the activities of the circulating and tissue RAS.53 In addition, it is also reported that cardiac function status54 and glucose55 and lipid56 metabolism modulate activities of circulating and tissue RAS. We did not collect information of subject profiles with regard to insulin sensitivity, cardiac function status, diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia in this study. Separate studies focusing on these points may clarify the effects of other modulating factors on circulating and tissue RASs, as well as plasma and urinary AGT levels.

Hypertensive patients treated with RAS blockers showed not only lower urinary AGT levels (Figure 3) but also lower values of systolic and diastolic blood pressures (Table 1). Thus, it is possible that the attenuation of an increase in urinary AGT levels in hypertensive patients treated with RAS blockers may be because of a decrease in blood pressure, as well as RAS blockade. Different antihypertensive regimens are also potential factors having different effects on the circulating and tissue RASs and plasma and urinary AGT levels. To address this issue, first, we have subdivided the hypertensive patients without RAS blockade group into 5 subgroups according to the antihypertensive regimens: patients without any antihypertensives, patients treated with diuretics, patients treated with calcium channel blockers, patients treated with β-blockers, and patients treated with α-blockers and analyzed plasma and urinary AGT levels, as well as systolic and diastolic blood pressures. As illustrated in Table S1, statistically there were no significant differences observed among the groups perhaps because of the low sample numbers in each subgroup. Second, we have subdivided the hypertensive patients in the RAS blockade group into 2 subgroups according to the antihypertensive regimens, patients treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and patients treated with angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers, and analyzed plasma and urinary AGT levels, as well as systolic and diastolic blood pressures. As illustrated in Table S2, these values are similar, and statistically significant differences were not observed between the 2 groups. Finally, we have compared plasma and urinary AGT levels, as well as systolic and diastolic blood pressures in hypertensive patients treated with calcium channel blockers and hypertensive patients treated with angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers. As illustrated in Table S3, whereas plasma AGT levels, as well as systolic and diastolic blood pressures, are similar between the 2 groups, urinary AGT levels appear to be lower in hypertensive patients treated with angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers. However, statistically significant differences were not observed between the 2 groups, likely because of the low sample numbers in each subgroup. A prospective study to compare the effects of the antihypertensive regimens (especially a comparison between calcium channel blockers and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers) on urinary AGT levels may help to clarify this issue.

Conclusion

UAGT/UCre levels were investigated in hypertensive patients and normotensive subjects. UAGT/UCre levels were significantly positively correlated with systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, urinary albumin:creatinine ratio, and urinary protein:creatinine ratio. UAGT/UCre levels were not correlated with race, gender, age, height, body weight, body mass index, serum sodium levels, serum potassium levels, serum creatinine levels, urinary sodium:creatinine ratio, urinary potassium:creatinine ratio, fractional excretion of sodium, plasma AGT levels, or estimated glomerular filtration rate. UAGT/UCre levels were significantly greater in hypertensive patients without RAS blockade compared with normotensive subjects. Importantly, hypertensive patients with RAS blockade did not have this augmentation. Because urinary AGT originates from the AGT that is formed and secreted by the proximal tubules and not from plasma, the enhanced urinary AGT in hypertensive patients reflects on activated intrarenal RAS and is not just a nonspecific consequence of proteinuria. These data suggest that urinary AGT is a potential novel biomarker of the intrarenal RAS status in hypertensive patients. The efficacy of RAS blockade to reduce the intrarenal RAS activity can, thus, be confirmed by measurements of urinary AGT excretion rates.

Perspectives

Although the relatively small sample size is a potential limitation, this study demonstrates a statistically significant relationship between urinary AGT and systolic/diastolic blood pressure and urinary albumin/protein in hypertensive patients. We recognize that a larger multicenter, randomized, control study is required to extend the clinical applicability of these observations. Based on these findings, a randomized clinical trial has been projected to establish a novel diagnostic test to identify those hypertensive patients most likely to respond to a RAS blockade, which could provide useful information to allow a mechanistic rationale for a more educated selection of an optimized approach to the treatment of hypertensive patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK072408); the National Center for Research Resources (P20RR017659); the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL026371); Louisiana Board of Regents (Research Commercialization and Educational Enhancement Program for Louisiana State University/Tulane University Health Sciences Centers’ Clinical and Translational Research Education and Commercialization Program); Tulane University Research Enhancement Fund (phase I); Tulane University Research Enhancement Fund (phase II); and the DCI Paul Teschan Research Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S, Hebert P, Fiebach NH, Eberlein KA, Godwin J, Qizilbash N, Taylor JO, Hennekens CH. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990;335:827–838. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ALLHAT officers and coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ALLHAT officers and coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs usual care: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT-llt) JAMA. 2002;288:2998–3007. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navar LG, Harrison-Bernard LM, Nishiyama A, Kobori H. Regulation of intrarenal angiotensin II in hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39:316–322. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, Nishiyama A. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: from physiology to the pathobiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:251–287. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dzau VJ, Re R. Tissue angiotensin system in cardiovascular medicine. A paradigm shift? Circulation. 1994;89:493–498. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baltatu O, Silva JA, Jr, Ganten D, Bader M. The brain renin-angiotensin system modulates angiotensin II-induced hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2000;35:409–412. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dell’Italia LJ, Meng QC, Balcells E, Wei CC, Palmer R, Hageman GR, Durand J, Hankes GH, Oparil S. Compartmentalization of angiotensin II generation in the dog heart evidence for independent mechanisms in intravascular and interstitial spaces. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:253–258. doi: 10.1172/JCI119529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazzocchi G, Malendowicz LK, Markowska A, Albertin G, Nussdorfer GG. Role of adrenal renin-angiotensin system in the control of aldosterone secretion in sodium-restricted rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;278:E1027–E1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.6.E1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danser AH, Admiraal PJ, Derkx FH, Schalekamp MA. Angiotensin I-to-II conversion in the human renal vascular bed. J Hypertens. 1998;16:2051–2056. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816121-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griendling KK, Minieri CA, Ollerenshaw JD, Alexander RW. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1994;74:1141–1148. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingelfinger JR, Pratt RE, Ellison K, Dzau VJ. Sodium regulation of angiotensinogen mRNA expression in rat kidney cortex and medulla. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1311–1315. doi: 10.1172/JCI112716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moe OW, Ujiie K, Star RA, Miller RT, Widell J, Alpern RJ, Henrich WL. Renin expression in renal proximal tubule. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:774–779. doi: 10.1172/JCI116296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casarini DE, Boim MA, Stella RC, Krieger-Azzolini MH, Krieger JE, Schor N. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme activity in tubular fluid along the rat nephron. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F405–F409. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.3.F405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komlosi P, Fuson AL, Fintha A, Peti-Peterdi J, Rosivall L, Warnock DG, Bell PD. Angiotensin I conversion to angiotensin II stimulates cortical collecting duct sodium transport. Hypertension. 2003;42:195–199. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000081221.36703.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould AB, Green D. Kinetics of the human renin and human substrate reaction. Cardiovasc Res. 1971;5:86–89. doi: 10.1093/cvr/5.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brasier AR, Li J. Mechanisms for inducible control of angiotensinogen gene transcription. Hypertension. 1996;27:465–475. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding Y, Davisson RL, Hardy DO, Zhu LJ, Merrill DC, Catterall JF, Sigmund CD. The kidney androgen-regulated protein promoter confers renal proximal tubule cell-specific and highly androgen-responsive expression on the human angiotensinogen gene in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28142–28148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.28142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura S, Mullins JJ, Bunnemann B, Metzger R, Hilgenfeldt U, Zimmermann F, Jacob H, Fuxe K, Ganten D, Kaling M. High blood pressure in transgenic mice carrying the rat angiotensinogen gene. EMBO J. 1992;11:821–827. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukamizu A, Sugimura K, Takimoto E, Sugiyama F, Seo MS, Takahashi S, Hatae T, Kajiwara N, Yagami K, Murakami K. Chimeric renin-angiotensin system demonstrates sustained increase in blood pressure of transgenic mice carrying both human renin and human angiotensinogen genes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11617–11621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohlender J, Menard J, Ganten D, Luft FC. Angiotensinogen concentrations and renin clearance: Implications for blood pressure regulation. Hypertension. 2000;35:780–786. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.3.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smithies O. Theodore cooper memorial lecture. A mouse view of hypertension. Hypertension. 1997;30:1318–1324. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merrill DC, Thompson MW, Carney CL, Granwehr BP, Schlager G, Robillard JE, Sigmund CD. Chronic hypertension and altered baroreflex responses in transgenic mice containing the human renin and human angiotensinogen genes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1047–1055. doi: 10.1172/JCI118497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Satou R, Katsurada A, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Hase N, Suzaki Y, Sigmund CD, Navar LG. Kidney-specific enhancement of ANG II stimulates endogenous intrarenal angiotensinogen in gene-targeted mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F938–F945. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00146.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sachetelli S, Liu Q, Zhang SL, Liu F, Hsieh TJ, Brezniceanu ML, Guo DF, Filep JG, Ingelfinger JR, Sigmund CD, Hamet P, Chan JS. RAS blockade decreases blood pressure and proteinuria in transgenic mice overexpressing rat angiotensinogen gene in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1016–1023. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavoie JL, Lake-Bruse KD, Sigmund CD. Increased blood pressure in transgenic mice expressing both human renin and angiotensinogen in the renal proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F965–F971. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00402.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smithies O, Kim HS. Targeted gene duplication and disruption for analyzing quantitative genetic traits in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3612–3615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HS, Krege JH, Kluckman KD, Hagaman JR, Hodgin JB, Best CF, Jennette JC, Coffman TM, Maeda N, Smithies O. Genetic control of blood pressure and the angiotensinogen locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2735–2739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue I, Nakajima T, Williams CS, Quackenbush J, Puryear R, Powers M, Cheng T, Ludwig EH, Sharma AM, Hata A, Jeunemaitre X, Lalouel JM. A nucleotide substitution in the promoter of human angiotensinogen is associated with essential hypertension and affects basal transcription in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1786–1797. doi: 10.1172/JCI119343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeunemaitre X, Soubrier F, Kotelevtsev YV, Lifton RP, Williams CS, Charru A, Hunt SC, Hopkins PN, Williams RR, Lalouel JM. Molecular basis of human hypertension: role of angiotensinogen. Cell. 1992;71:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90275-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao YY, Zhou J, Narayanan CS, Cui Y, Kumar A. Role of C/A polymorphism at –20 on the expression of human angiotensinogen gene. Hypertension. 1999;33:108–115. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishigami T, Umemura S, Tamura K, Hibi K, Nyui N, Kihara M, Yabana M, Watanabe Y, Sumida Y, Nagahara T, Ochiai H, Ishii M. Essential hypertension and 5′ upstream core promoter region of human angiotensinogen gene. Hypertension. 1997;30:1325–1330. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Expression of angiotensinogen mRNA and protein in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:431–439. doi: 10.1681/asn.v123431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Enhancement of angiotensinogen expression in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2001;37:1329–1335. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Urinary excretion of angiotensinogen reflects intrarenal angiotensinogen production. Kidney Int. 2002;61:579–585. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobori H, Nishiyama A, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Urinary angiotensinogen as an indicator of intrarenal angiotensin status in hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:42–49. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000050102.90932.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobori H, Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Ozawa Y, Navar LG. AT1 receptor mediated augmentation of intrarenal angiotensinogen in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;43:1126–1132. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000122875.91100.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katsurada A, Hagiwara Y, Miyashita K, Satou R, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Navar LG, Kobori H. Novel sandwich ELISA for human angiotensinogen. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F956–F960. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00090.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto T, Nakagawa T, Suzuki H, Ohashi N, Fukasawa H, Fujigaki Y, Kato A, Nakamura Y, Suzuki F, Hishida A. Urinary angiotensinogen as a marker of intrarenal angiotensin II activity associated with deterioration of renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1558–1565. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006060554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobori H, Ohashi N, Katsurada A, Miyata K, Satou R, Saito T, Yamamoto T. Urinary angiotensinogen as a potential biomarker of severity of chronic kidney diseases. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2008;2:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, Kusek JW, Van Lente F. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:247–254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Marsh J, Stevens LA, Kusek JW, Van Lente F. Expressing the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate with standardized serum creatinine values. Clin Chem. 2007;53:766–772. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.077180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ingelfinger JR, Zuo WM, Fon EA, Ellison KE, Dzau VJ. In situ hybridization evidence for angiotensinogen messenger RNA in the rat proximal tubule. An hypothesis for the intrarenal renin angiotensin system. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:417–423. doi: 10.1172/JCI114454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darby IA, Sernia C. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry of renal angiotensinogen in neonatal and adult rat kidneys. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;281:197–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00583388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lantelme P, Rohrwasser A, Gociman B, Hillas E, Cheng T, Petty G, Thomas J, Xiao S, Ishigami T, Herrmann T, Terreros DA, Ward K, Lalouel JM. Effects of dietary sodium and genetic background on angiotensinogen and renin in mouse. Hypertension. 2002;39:1007–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000016177.20565.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rohrwasser A, Morgan T, Dillon HF, Zhao L, Callaway CW, Hillas E, Zhang S, Cheng T, Inagami T, Ward K, Terreros DA, Lalouel JM. Elements of a paracrine tubular renin-angiotensin system along the entire nephron. Hypertension. 1999;34:1265–1274. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogawa S, Mori T, Nako K, Kato T, Takeuchi K, Ito S. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers reduce urinary oxidative stress markers in hypertensive diabetic nephropathy. Hypertension. 2006;47:699–705. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000203826.15076.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mezzano S, Droguett A, Burgos ME, Ardiles LG, Flores CA, Aros CA, Caorsi I, Vio CP, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J. Renin-angiotensin system activation and interstitial inflammation in human diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(suppl 86):S64–S70. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s86.12.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mezzano SA, Aros CA, Droguett A, Burgos ME, Ardiles LG, Flores CA, Carpio D, Vio CP, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J. Renal angiotensin II up-regulation and myofibroblast activation in human membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(suppl 86):S39–S45. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s86.8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tell GS, Rutan GH, Kronmal RA, Bild DE, Polak JF, Wong ND, Borhani NO. Correlates of blood pressure in community-dwelling older adults. The cardiovascular health study. Cardiovascular health study (CHS) collaborative research group. Hypertension. 1994;23:59–67. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Larson MG, O’Donnell CJ, Roccella EJ, Levy D. Differential control of systolic and diastolic blood pressure: Factors associated with lack of blood pressure control in the community. Hypertension. 2000;36:594–599. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McFarlane SI, Kumar A, Sowers JR. Mechanisms by which angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors prevent diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:30H–37H. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00432-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dostal DE, Baker KM. The cardiac renin-angiotensin system: Conceptual, or a regulator of cardiac function? Circ Res. 1999;85:643–650. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.7.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leehey DJ, Singh AK, Alavi N, Singh R. Role of angiotensin II in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2000;58:S93–S98. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strazzullo P, Galletti F. Impact of the renin-angiotensin system on lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004;13:325–332. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.