Abstract

Raman spectroscopic diffuse tomographic imaging has been demonstrated for the first time. It provides a non-invasive, label-free modality to image the chemical composition of human and animal tissue and other turbid media. This technique has been applied to image the composition of bone tissue within an intact section of a canine limb. Spatially-distributed 785-nm laser excitation was employed to prevent thermal damage to the tissue. Diffuse emission tomography reconstruction was used, and the location that was recovered has been confirmed by micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) images.

With recent advances, diffuse tomography shows promise for in vivo clinical imaging1, 2. In principle, algorithms developed for fluorescence imaging in tissue can be applied to Raman signals. Although the Raman effect is weaker than fluorescence, the scattered signal is detectable, and thus tomography is achievable. Here we demonstrate the first diffuse tomography reconstructions based on Raman scatter.

Raman mapping and imaging are well-established techniques for examining material surfaces3. Subsurface mapping of simple planar objects was reported recently4, 5 using fiber optic probes with spatially-separated injection and collection fibers6. Non-invasive measurements of bone Raman spectra were demonstrated at depths of 5 mm below the skin5.

Bone is promising for Raman tomography, because the spectra are rich in compositional information7, which reflect bone maturity and health. Spectroscopically-measured bone composition changes have been correlated with aging8 and susceptibility to osteoporotic fracture9. The Raman spectrum of bone mineral is easily distinguished from the spectra of proteins and other organic tissue constituents, facilitating recovery of even weak signals by multivariate techniques.

Assessments of bone quantity and quality are essential to detect and monitor fracture risk and fracture healing with disease or injury. Common sites for fracture with osteoporosis are the spine, proximal femur, and distal radius. Stress fractures are most frequently seen in the weight-bearing sites of the tibia and metatarsals. Fracture risk depends on bone geometry, architecture, and material properties, as well as the nature of applied load (magnitude, rate, and direction). As a result, non-invasive imaging and non-destructive analysis methods have been developed to assess many of these bone attributes that are increasingly important to clinical practice and basic research in orthopaedics10. Current clinical in vivo methods include dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), quantitative computed tomography (QCT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound and most recently high-resolution peripheral QCT. Ex vivo analyses of bone specimens from patients or animals have also utilized these and other techniques.

In this study, we couple micro-CT and diffuse optical tomography with Raman spectroscopy to recover spatial and composition information from bone tissue ex vivo. We demonstrate the first reconstruction-based recovery of Raman signals through thick tissues to yield molecular information about subsurface bone tissue. Reconstructions from transcutaneous Raman measurements are challenging, because layers of skin, muscle, fat, and connective tissue lie over the bone sites of interest. These layers have different optical properties and thus variably scatter and polarize the injected light.

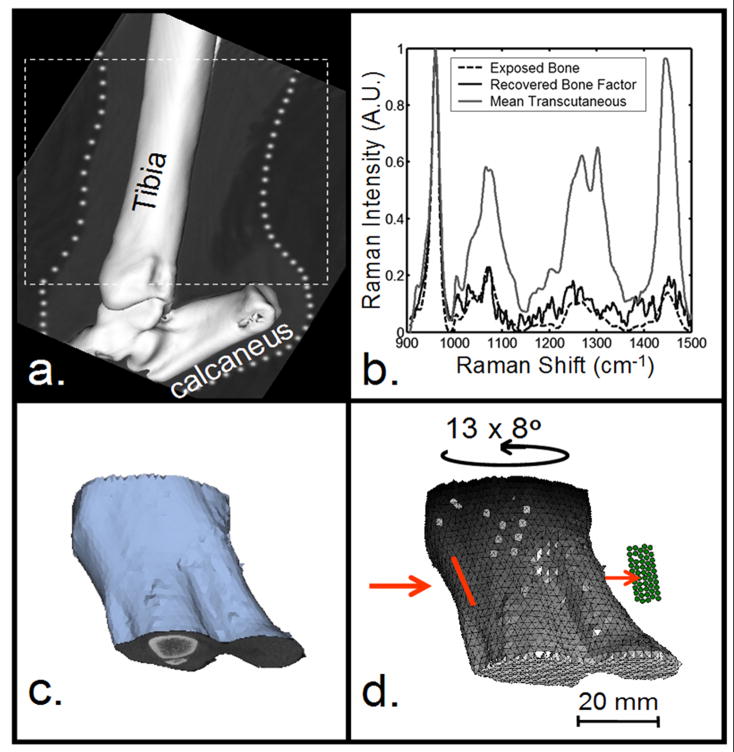

We chose a canine model because of specimen availability and a bone size similar to human bone. We selected the tibia, a site that is clinically important and has relatively few overlying soft tissues. Measurements were made on the medial surface, where the only additional optical barrier is the crural extensor retinaculum ligament. The canine hind limb was harvested from an animal euthanized in an approved (UCUCA) University of Michigan study. The section of the limb distal to the knee was excised and scanned using in vivo micro-CT (eXplore Locus RS, GE Healthcare, Ontario, Canada). The tibia was scanned at 80kV and 450μA with an exposure time of 100 ms using a 360-degree scan technique. The image was reconstructed at a 93-μm voxel resolution (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Development of mesh for tomographic reconstruction. a) Micro-CT image of canine hind limb section. b) Raman spectra of limb section. c) Geometric image of tissues from micro-CT data. d) Volumetric mesh created from (c). Input coordinates for reconstruction: tomographic projections and their associated scores. Illumination line (red) and collection fibers (green).

The Raman system (785-nm excitation wavelength) and preprocessing and data analysis protocols for the non-invasive recovery of bone spectra have been described previously5. Briefly, hair was removed, and glycerol was applied for optical clearing. Sixty-second acquisitions were made at 10 different ring inner diameters between 6 and 16 mm. Prior to tomographic reconstruction, a bone Raman factor was recovered transcutaneously in a backscattered geometry using data from three ring diameters that maximized bone tissue contributions to the Raman signal. After transcutaneous measurements were completed, overlying tissue was removed, and the exposed bone spectrum was obtained (Fig. 1b). The cross-correlation coefficient between the transcutaneous bone factor and exposed bone spectrum was 0.97, indicating factor recovery was successful.

The same laser, spectrograph, and detector were used for tomography. The specimen was mounted on a 360º rotation stage, and transmission (180º illumination/collection) measurements were taken transcutaneously. The laser (200 mW at the specimen) was focused to a rectangle (approx. 8×1.5 mm) along the long axis of the tibia. Although the 1.67 W/cm2 power density was above the ANSI Z163.1 threshold limit value, no thermal damage was observed. The 5×10 rectangular array of 100-μm core collection fibers were focused on the specimen 180º from the laser illumination point (Fig. 1d). At the spectrograph, the collection fibers were arranged in a line. Thirteen projections were obtained at 8º intervals spanning the range shown in Fig. 2d. Raman scatter was collected for 5 minutes at each projection. The score (dot product) was calculated between the recovered bone factor and the Raman transmission signal collected by each fiber for all projections. These scores were used as inputs for tomographic reconstruction.

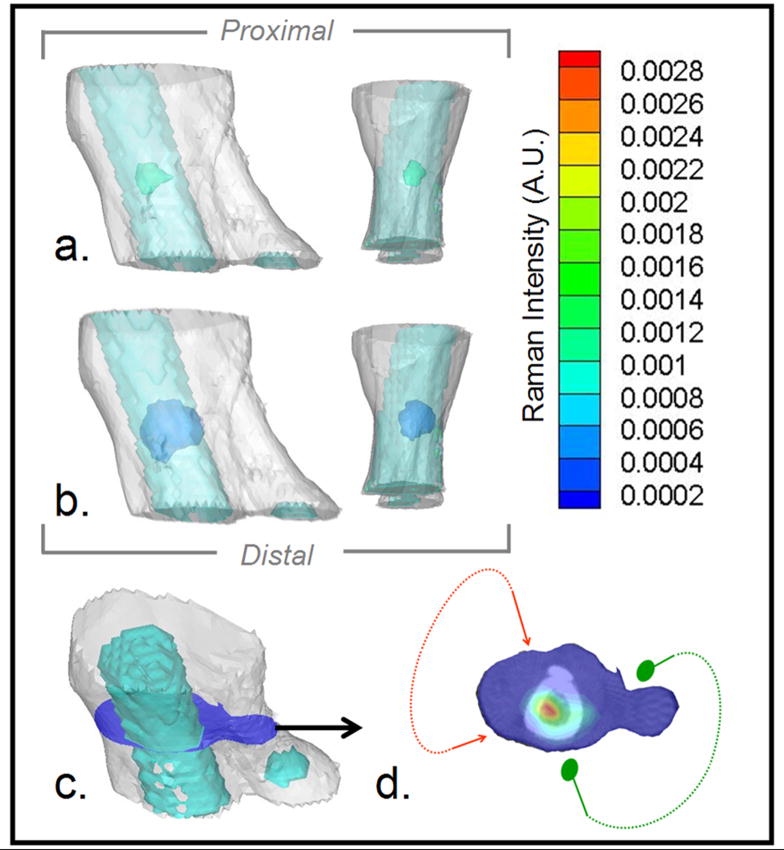

Fig. 2.

Raman tomographic images of canine bone tissue. a) Medial and anterior views of soft tissue mesh (white) and bone surface mesh of tibia and calcaneus (turquoise) overlaid with 50% contrast isosurface of the reconstructed 3-D Raman image of bone (green). b) Same view as (a) overlaid with 10% contrast isosurface of the reconstructed Raman image of bone (blue). c) 3-D mesh of limb section (white), including bone (turquoise), illustrating location of the cross-section (blue) containing the highest Raman scatter intensity. d) Raman intensity at cross-section in (c) in pseudo-color overlaid on the micro-CT image of the bone, showing range of illumination (red arrows) and collection (green dots) positions.

For the reconstruction, a geometric model was created using the micro-CT data. Skin and bone tissues were segmented using thresholding and region-growing tools in the modeling software (Mimics, Materialise Inc., Ann Arbor, MI). The modeled outer surface of the canine limb section (Fig. 1c) was used to generate a volumetric grid for computation. The uniform 2-mm resolution volume mesh contained 8218 nodes and 40969 tetrahedral elements (Fig. 1d). In the mesh, the bone and background (assumed skin) regions based on segmentation from the CT images were tagged with the appropriate scattering and absorption coefficients. The excitation and emission optical properties were assumed to be identical.

For tomographic reconstruction, calibrations were performed using a tissue phantom (9-mm diameter Teflon® sphere placed 10 mm below the surface of a cylindrical phantom (diameter 59 mm, height 44.5 mm) composed of 1% Intralipid/agarose gel. A data-scaling factor, computed as the average difference between experimental and model-generated measurements from the phantom, was subtracted from the canine tibia dataset to compensate for the model-data mismatch. This approach, which is commonly used in diffuse tomography to scale the data set to the model and to avoid calibration errors and image artifacts, simply shifts the intensities up or down to match the model but does not affect the spatial recovery within the image.

The Raman reconstructions were based on NIRFAST (http://nir.thayer.dartmouth.edu/), a reconstruction software toolbox developed at Dartmouth for photon emission imaging2, 11, 12. The toolbox uses a finite element model to solve a set of coupled diffusion equations, which predict the way the excitation fluence and the Raman emission fluence travel through the highly-scattering media. This model, known to be approximate in small tissues, is sufficient for small animal studies with length scales similar to the dog leg. A modified iterative Newton’s method minimizing the least squares norm of model-data differences was used for reconstruction. The tool-box was modified to incorporate the line focus of the sources. Since diffuse optical image reconstruction is ill-posed and ill-conditioned, we used regularization to stabilize the inversion. The starting regularization value was 100, relative to the diagonal of the Hessian matrix to be inverted, and this value was based upon the preliminary phantom experiments, as has been done in our diffuse tomography imaging studies previously. However, the reconstruction of the Raman signal by itself did not assume any knowledge of location of inner tissues.

Raman diffuse tomography was used to reconstruct the canine hind limb section (Fig. 2). The medial-lateral limb thickness in the region of interest ranged between 24 and 45 mm. The signal/noise ratio, measured using the PO4−3 ν1 peak intensity, ranged from 0 to 5.7. Two reconstructed Raman isosurfaces were mapped onto the true location of the tibia (Figs.2a-b). Reconstructions appeared artificially spherical, possibly due to the diffuse propagation of light through tissue, which inherently results in diffuse tomography images with blurred features, and to Gaussian-shaped object recovery. The peaked intensity in the center of the bone is an artifact of this process. This problem was most apparent at high and low intensities. Isosurface thresholds between 10% (Fig. 2a) and 50% (Fig. 2b) preserved non-spherical shapes. Despite tissue thickness, the periosteal perimeter of the reconstructed image corresponded well to the true bone contour (Figs. 2c–d). The highest Raman bone signal was found in the center of the bone (Fig. 2d), which is likely an artifact of the Gaussian-type blurring that occurs in diffuse tomography. Because light passed through both the tibia and fibula in few projections, the fibula was not accurately reconstructed.

Without spatial priors in the reconstruction and with the limited mesh resolution, localization of the bone was imperfect. However, our Raman tomography approach provides the means to incorporate a more sophisticated reconstruction, such as with spatial priors. Although we used a diffusion model of light transport, an approximation commonly made for tissue studies, the light was likely not truly diffuse. Future work will focus on coupling more linear transport forward models into our promising imaging application, along with the use of spatial priors to provide better localization13.

This proof-of-principle study provides evidence that Raman tomographic images can be obtained in vivo. We also show that the integration of Raman tomography measurements with CT (and by extension, MRI) is feasible. Future probe designs will focus on examining composition changes in the tissue. Improved probe geometry will allow us to reduce power density and impose spatial constraints on the recovery of composition properties for tissue imaged by the clinical modality. This dual imaging technique also provides a better estimate of the Raman signal, and the spatial mapping improves the template for accurate image recovery11, 13.

Acknowledgments

Supported through NIH grants R01-AR055222 (M. D. M., S. A. G.), NRSA T90-DK070071-03 (J. H. C.), T32-GM008353 (K. A. D), P01-CA080139 (B. W. P., S. S) and R01-CA120368 (B. W. P.)

References

- 1.Ntziachristos V, Schellenberger EA, Ripoli J, Yessayan D, Graves E, Bogdanov A, Jr, Josephson L, Weissleder R. Visualization of antitumor treatment by means of a fluorescence molecular tomography with an annexin V-Cy5.5 conjugate. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2004;101(33):12294–12299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401137101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis SC, Pogue BW, Dehghani H, Paulsen KD. Contrast-detail analysis characterizing diffuse optical fluorescence tomography image reconstruction. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2005;10(5):050501. doi: 10.1117/1.2114727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treado PJ, Nelson MP. Raman Imaging. In: Lewis IR, Edwards HGM, editors. Handbook of Raman Spectroscopy. Marcel Dekker, Inc; New York: 2001. pp. 191–249. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulmerich MV, Finney WF, Fredericks RA, Morris MD. Subsurface Raman Spectroscopy and Mapping Using a Globally Illuminated Non-Confocal Fiber-Optic Array Probe in the Presence of Raman Photon Migration. Appl Spectrosc. 2006;60(2):109–114. doi: 10.1366/000370206776023340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulmerich MV, Dooley KA, Vanasse TM, Goldstein SA, Morris MD. Subsurface and Transcutaneous Raman Spectroscopy and Mapping using Concentric Illumination Rings and Collection with a Circular Fiber Optic Array. Appl Spectrosc. 2007;61:671–678. doi: 10.1366/000370207781393307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matousek P. Deep non-invasive Raman spectroscopy of living tissue and powders. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36(8):1292–1304. doi: 10.1039/b614777c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carden A, Morris MD. Application of vibrational spectroscopy to the study of mineralized tissue (review) J Biomed Opt. 2000;5(3):259–268. doi: 10.1117/1.429994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akkus O, Adar F, Schaffler MB. Age-related changes in physicochemical properties of mineral crystals are related to impaired mechanical function of cortical bone. Bone. 2004;34(3):443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCreadie BR, Morris MD, Chen T-C, Sudhaker Rao D, Finney WF, Widjaja E, Goldstein SA. Bone tissue compositional differences in women with and without osteoporotic fracture. Bone. 2006;39(6):1190–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer-Kuckuk P, Boskey AL. Molecular imaging promotes progress in orthopedic research. Bone. 2006;39(5):965–977. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter CM, Pogue BW, Jiang S, Dehghani H, Wang X, Paulsen KD, Wells WA, Forero J, Kogel C, Weaver JB, Poplack SP, Kaufman PA. Image-guided optical spectroscopy provides molecular-specific information in vivo: MRI-guided spectroscopy of breast cancer hemoglobin, water, and scatterer size. Opt Lett. 2007;32(8):933–935. doi: 10.1364/ol.32.000933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis SC, Dehghani H, Wang J, Jiang S, Pogue BW, Paulsen KD. Image-guided diffuse optical fluorescence tomography implemented with Laplacian-type regularization. Optics Express. 2007;15:4066–4082. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.004066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pogue BW, Davis SC, Song X, Brooksby BA, Dehghani H, Paulsen KD. Image analysis methods for diffuse optical tomography. J Biomed Optics. 2006;11(3):033001. doi: 10.1117/1.2209908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]