Abstract

Introduction:

Asian Americans, along with other ethnic minorities, have been described to be more likely than Whites to be light and intermittent smokers. Characterizing Asian American smoking behavior accurately on a population level requires oversampling groups of different national origin and including non–English-speaking participants.

Methods:

We analyzed the California Health Interview Survey to compare moderate/heavy (≥10 cigarettes/day), light (0–9 cigarettes/day), and intermittent (not daily) smoking patterns in Asian Americans with those of Whites. We also examined whether social and demographic factors that had been associated with Asian American smoking prevalence also were associated with light and intermittent smoking patterns in each of the national origin groups.

Results:

Most Asian American smokers were more likely to be light and intermittent smokers (range = 36.6%–61.5% for men and 29.9%–81.5% for women) compared with Whites, with lower mean cigarette consumption. Asian American light and intermittent smokers were more likely than moderate/heavy smokers to be women (odds ratio [OR] = 2.12, 95% CI = 1.14–3.94), highly educated (OR = 3.16, 95% CI = 1.21–8.28), not Korean (compared with Chinese; OR = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.13–0.79), and bilingual speakers with high English language proficiency compared with English-only speakers (OR = 2.83, 95% CI = 1.21–6.84). Asian American intermittent smokers were more likely than daily smokers to be women (OR = 2.25, 95% CI = 1.08–4.72) and to have lower household income.

Discussion:

The predominance of Asian American light and intermittent smoking patterns has important implications for developing effective tobacco control outreach. Further studies are needed to elaborate the relationship between biological, psychosocial, and cultural factors influencing Asian American smoking intensity.

Introduction

Ethnic minorities have been described to be more likely than non-Latino Whites (henceforth, Whites) to be light and intermittent smokers (Gilpin et al., 2003; Hassmiller, Warner, Mendez, Levy, & Romano, 2003; Okuyemi et al., 2002; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1998; Wortley, Husten, Trosclair, Chrismon, & Pederson, 2003). Characterizing Asian American smoking behavior accurately on a population level, however, requires oversampling groups of different national origin and including non–English-speaking participants (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004; Tang, Shimizu, & Chen, 2005).

Findings from the two population-based studies that were conducted in this manner reported cigarettes per day in aggregate for Asian Americans. The National Latino and Asian American Study reported a median of 9 cigarettes/day (Chae, Gavin, & Takeuchi, 2006), and the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) reported a mean of 10 cigarettes/day for men and 7.8 cigarettes/day for women (Maxwell, Bernaards, & McCarthy, 2005; Tang et al., 2005). It is not known whether variables associated with Asian American smoking prevalence, gender, Asian national origin, birthplace, and English proficiency (Chae et al., 2006; Kim, Ziedonis, & Chen, 2007; Maxwell et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2005) are similarly associated with Asian American light and intermittent smoking behavior.

For this study, we describe Asian American light and intermittent smokers using the CHIS, which surveyed the largest number of Asian Americans. We compared smoking intensity patterns for Asian American groups of different national origin with those for Whites. We also investigated social and demographic variables for their associations with light and intermittent smoking patterns among Asian Americans only.

Methods

Dataset

The 2003 CHIS is a population-based household survey conducted by random digit dialing that oversampled areas with high concentrations of Koreans and Vietnamese; geographic samples were supplemented by telephone numbers for group-specific surnames drawn from listed telephone directories (CHIS, 2005). The survey was conducted in Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese), Vietnamese, and Korean languages by trained bilingual/bicultural interviewers. In the 2003 CHIS, the household screener rate was 56% and the extended adult interview response rate was 60%, for an overall response rate of 33.5%. The overall response rate is not very different from two other random-digit–dialed surveys conducted in California (CHIS, 2005). Between 11% and 13% of the total completed screener and adult interviews were done in languages other than English; 87% of the Vietnamese interviews were conducted in Vietnamese and 84% of the Korean interviews were conducted in Korean. By including the multiple Asian language interviews for these populations, the reduction of nonresponse bias is probably greater than the simple response rate computations suggest (CHIS, 2005).

Measures

Current smokers were defined in the survey as ever having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in a lifetime, and whether they smoked now or not at all. Current smokers were asked whether they smoked daily or not (intermittent), and how many cigarettes they consumed on days smoked over the past 30 days. We defined smoking intensity as follows: moderate or heavy (≥10 cigarettes/day), light (1–9 cigarettes/day), and intermittent. The cutoff of 10 cigarettes/day has been suggested as more reflective of heavier ethnic minority smoking patterns (Okuyemi et al., 2002).

Demographic variables included age, gender, education, marital status, poverty level, and Asian national origin. The CHIS public-use dataset relates self-reported household total annual income to federal poverty level guidelines, divided into four poverty levels. We used the University of California, Los Angeles’ Center for Health Policy Research variable describing Asian groups who self-identify with different national origins: Chinese, Filipino, South Asian, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and other Asian (defined as Cambodian/other single Asian/multiple Asian).

We used birthplace (foreign born vs. U.S. born) and English language proficiency as proxy measures of acculturation since these measures were significantly associated with Asian American smoking prevalence in the National Latino and Asian American Study (Chae et al., 2006) and CHIS (Maxwell et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2005). We modified an English language proficiency variable from a previous CHIS analysis (Tang et al., 2005) into three levels of English language proficiency: English only, bilingual with high proficiency (“spoke English very well/well”), and bilingual with low proficiency (“spoke English not well/not at all”).

Data analyses

The seven Asian American groups of different national origin were compared in terms of demographics and smoking-related behavior using a modified F test suitable for complex survey data. We also used this F test to compare the prevalence of moderate/heavy, light, and intermittent smoking across Asian American groups of different national origin as well as Whites.

Multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess the association of social and demographic variables with (a) light and intermittent smoking compared with moderate/heavy smoking and (b) intermittent smoking compared with daily smoking among Asian Americans. We also tested for interactions between gender and English language proficiency, as well as gender and birthplace, since these interactions had been reported for Asian American current smoking prevalence (Chae et al., 2006; Maxwell et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2005). All analyses were performed in 2007 with Stata version 8.0, using the “svr” functions, which use the replication weights supplied with the CHIS data to obtain weighted estimates and SEs that account for the complex survey design.

Results

The survey interviewed a total of 3,875 Asian Americans, only 479 of whom were smokers and were included in this analysis. Asian American smokers included 212 moderate/heavy, 128 light, and 139 intermittent smokers. Among White respondents, there were 2,496 moderate/heavy, 450 light, and 1,055 intermittent smokers.

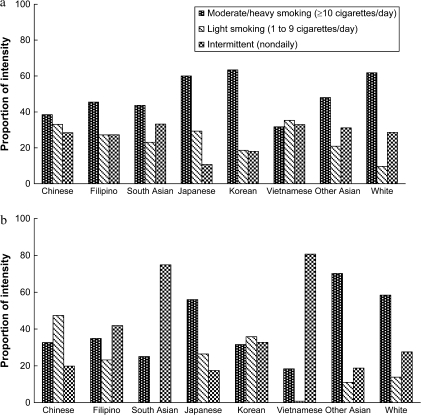

Figure 1a and b show that, compared with White smokers, most Asian American smokers, both men and women, were more likely to report light or intermittent smoking than moderate/heavy smoking. Moderate/heavy smokers represented well over half of the White men and women smokers, but among Asian national origin groups, only Japanese and Korean American men and Japanese and other Asian American women had over half of smokers similarly represented.

Figure 1.

Top panel: Proportions of cigarette smoking intensity among Asian American men by national origin groups and White men, California Health Interview Survey, 2003. Test for heterogeneity across eight groups (p < .0001). The p values comparing cigarette smoking intensity in White men with Chinese (p < .0001), Filipino (p = .002), South Asian (p = .18), Japanese (p = .02), Korean (p = .10), Vietnamese (p < .0001), and other Asian (p = .40). Sample sizes: Chinese = 60, Filipino = 103, South Asian = 37, Japanese = 21, Korean = 47, Vietnamese = 62, and other Asian = 22. Bottom panel: Proportions of cigarette smoking intensity among Asian American women by national origin groups and White women, California Health Interview Survey, 2003. Test for heterogeneity across eight groups (p = .001). The p values comparing cigarette smoking intensity in White women with Chinese (p = .02), Filipino (p = .05), South Asian (p = .04), Japanese (p = .28), Korean (p = .01), Vietnamese (p = .02), and other Asian (p = .79). Sample sizes: Chinese = 14, Filipino = 44, South Asian = 7, Japanese = 31, Korean = 18, Vietnamese = 6, and other Asian = 7.

Within smoking intensity groups, most Asian American smokers reported lower mean cigarette consumption than Whites. The lower mean cigarette consumption was also demonstrated for the Asian American subgroups, of which over half were moderate/heavy smokers, for both men (Japanese, 14.5; Korean, 14.2; and White, 19.2) and women (Japanese, 11.6; other Asian, 11.8; and White, 16.7). Slightly higher mean cigarette consumption, compared with White counterparts, was reported for a few groups: moderate/heavy smoker Korean women (17.3 vs.16.7), light smoker Japanese and Korean men (5.5 and 5.6 vs. 5.5), light smoker Japanese women (6.8 vs. 5.5), and intermittent smoker Chinese and Filipino men (7.2 and 5.5 vs. 4.8).

Table 1 demonstrates the prevalence of each Asian American smoking pattern within each demographic variable (by row), separated by gender. Poverty level was statistically significant for men, with half of the poorest category being intermittent smokers and about half of the wealthier categories being moderate/heavy smokers. Age and education were statistically significant for women, with the older smokers more likely to be daily smokers and the less educated more likely to be moderate/heavy smokers.

Table 1.

Demographics of moderate/heavy, light, and intermittent smoking among Asian American men and women, California Health Interview Survey, 2003

| Men |

Women |

|||||

| Moderate/heavy (n = 165) | Light (n = 93) | Intermittent (n = 94) | Moderate/heavy (n = 47) | Light (n = 35) | Intermittent(n = 45) | |

| Age (years)a | ||||||

| 18–24 | 26.8 | 27.4 | 45.8 | 45.3 | 17.8 | 36.9 |

| 25–44 | 46.0 | 31.3 | 22.7 | 20.1 | 29.7 | 50.1 |

| 45–64 | 53.4 | 21.2 | 25.4 | 61.6 | 16.5 | 21.9 |

| ≥65 | 52.7 | 27.4 | 19.9 | 24.5 | 64.5 | 11.0 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 53.4 | 23.6 | 23.0 | 32.3 | 27.2 | 40.4 |

| Former married | 41.5 | 30.6 | 27.8 | 61.8 | 24.9 | 13.4 |

| Single | 34.6 | 32.8 | 32.5 | 33.7 | 23.2 | 43.2 |

| Educationb | ||||||

| <High school degree | 47.7 | 21.3 | 31.0 | 68.3 | 28.8 | 2.9 |

| High school grad/college | 45.6 | 27.7 | 26.7 | 52.6 | 22.9 | 24.5 |

| ≥College grad | 43.5 | 30.2 | 26.2 | 15.5 | 27.6 | 56.9 |

| Povertyc | ||||||

| 0%–99% FPL | 28.2 | 20.6 | 51.2 | 46.0 | 25.6 | 28.3 |

| 100%–199% FPL | 44.6 | 34.3 | 21.1 | 52.6 | 17.8 | 29.6 |

| 200%–299% FPL | 45.5 | 39.5 | 14.9 | 55.9 | 37.8 | 6.3 |

| ≥300% FPL | 50.6 | 25.1 | 24.2 | 33.3 | 24.2 | 42.4 |

| National origin | ||||||

| Chinese | 38.5 | 33.1 | 28.4 | 32.7 | 47.4 | 19.9 |

| Filipino | 45.5 | 27.2 | 27.3 | 34.9 | 23.2 | 41.9 |

| South Asian | 43.7 | 23.1 | 33.2 | 25.1 | 0 | 74.9 |

| Japanese | 60.0 | 29.3 | 10.7 | 56.0 | 26.5 | 17.5 |

| Korean | 63.4 | 18.6 | 18.0 | 31.6 | 35.8 | 32.6 |

| Vietnamese | 31.7 | 35.3 | 33.0 | 18.4 | 0.8 | 80.7 |

| Other | 48.0 | 20.9 | 31.1 | 70.2 | 11.1 | 18.8 |

| Nativity | ||||||

| U.S. born | 38.5 | 32.2 | 29.2 | 47.1 | 21.1 | 31.8 |

| Foreign born | 46.5 | 26.9 | 26.7 | 35.8 | 28.0 | 36.2 |

| English proficiency | ||||||

| English only | 63.7 | 20.0 | 16.3 | 39.4 | 25.3 | 35.3 |

| Bilingual high | 38.5 | 32.5 | 29.9 | 36.8 | 22.4 | 40.8 |

| Bilingual low | 50.0 | 20.5 | 29.5 | 53.2 | 33.7 | 13.2 |

Note. FPL, federal poverty level.

p = .02 for women.

p = .01 for women.

p = .01 for men.

In the multivariate analysis comparing Asian American light and intermittent smokers to moderate/heavy smokers (Table 2), gender, education, national origin, and English language proficiency were statistically significant. Compared with men, women were more likely to be light or intermittent smokers than moderate/heavy smokers. Similarly, compared with smokers who have less than a high school education, smokers who have a college education were more likely to be light or intermittent smokers than moderate/heavy smokers. Compared with Chinese Americans, Korean Americans were less likely to be light or intermittent smokers than moderate/heavy smokers. Compared with smokers who spoke English only, Asian Americans who were bilingual with high English proficiency were more likely to be light or intermittent smokers than moderate/heavy smokers.

Table 2.

Factors associated with (a) light/intermittent versus moderate/heavy smoking and (b) intermittent versus daily smoking among Asian Americans, California Health Interview Survey, 2003

| Odds ratio for light/intermittent versus moderate/heavy smoking (95% CI) | p value | Odds ratio for intermittent versus daily smoking (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 (reference) | ||||

| 25–44 | 0.73 (0.24–2.27) | .59 | 0.43 (0.14–1.30) | .13 |

| 45–64 | 0.45 (0.14–1.48) | .19 | 0.41 (0.13–1.26) | .12 |

| ≥65 | 0.90 (0.17–4.86) | .90 | 0.34 (0.09–1.37) | .13 |

| Gender | ||||

| Men (reference) | ||||

| Women | 2.12 (1.14–3.94) | .02* | 2.25 (1.08–4.72) | .03* |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married (reference) | ||||

| Formerly married | 0.89 (0.33–2.36) | .81 | 0.75 (0.28–2.02) | .56 |

| Single | 1.40 (0.60–3.25) | .43 | 0.95 (0.39–2.33) | .91 |

| Education | ||||

| <High school degree (reference) | ||||

| High school grad/college | 1.53 (0.59–3.95) | .38 | 1.41 (0.53–3.73) | .48 |

| ≥College grad | 3.16 (1.21–8.28) | .02* | 2.41 (0.80–7.26) | .12 |

| Poverty | ||||

| 0%–99% FPL (reference) | ||||

| 100%–199% FPL | 0.59 (0.23–1.52) | .27 | 0.42 (0.16–1.15) | .09 |

| 200%–299% FPL | 0.49 (0.16–1.47) | .20 | 0.18 (0.06–0.58) | .005* |

| ≥300% FPL | 0.48 (0.19–1.23) | .12 | 0.50 (0.21–1.20) | .12 |

| National origin | ||||

| Chinese (reference) | ||||

| Filipino | 0.72 (0.29–1.78) | .47 | 1.31 (0.47–3.65) | .60 |

| South Asian | 0.62 (0.22–1.79) | .38 | 1.83 (0.63–5.34) | .26 |

| Japanese | 0.50 (0.14–1.76) | .28 | 0.50 (0.13–1.89) | .30 |

| Korean | 0.32 (0.13–0.79) | .01* | 0.62 (0.24–1.61) | .32 |

| Vietnamese | 1.67 (0.69–4.05) | .25 | 1.93 (0.66–5.64) | .22 |

| Other | 0.42 (0.12–1.42) | .16 | 1.15 (0.24–5.57) | .86 |

| Nativity | ||||

| U.S. born (reference) | ||||

| Foreign born | 0.53 (0.20–1.43) | .21 | 0.71 (0.25–2.01) | .51 |

| English proficiency | ||||

| English only (reference) | ||||

| Bilingual high | 2.83 (1.21–6.64) | .02* | 1.79 (0.70–4.59) | .22 |

| Bilingual low | 2.02 (0.75–5.42) | .16 | 2.26 (0.77–6.60) | .13 |

Note. FPL, federal poverty level; *Statistically significant.

In the multivariate analysis comparing Asian American intermittent to daily smokers (see Table 2), gender was the only variable that retained statistical significance from the previous model, and poverty level reached statistical significance. Women were more likely than men to be intermittent than daily smokers. Smokers reporting 200%–299% federal poverty level were less likely than the poorest (0%–99% federal poverty level) to be intermittent smokers than daily smokers.

We did not find any interactions between gender and birthplace. A trend for statistical significance was observed for interaction between gender and English proficiency both in comparing light or intermittent smokers with moderate/heavy smokers (p = .11) as well as in comparing intermittent smokers with daily smokers (p = .14).

Discussion

Our study shows that, compared with Whites, most Asian American smokers were more likely to be light or intermittent smokers, consistent with previous studies and with generally lower mean cigarette consumption. This is the first study to demonstrate that social and demographic factors associated with Asian American smoking prevalence also are associated with light and intermittent smoking patterns: Asian American light and intermittent smokers were more likely (than moderate/heavy smokers) to be women, highly educated, not Korean American (compared with Chinese American), and bilingual speakers with high English language proficiency (compared with English-only speakers); Asian American intermittent smokers were more likely (than daily smokers) to be women and the most impoverished.

We only found a trend for statistical significance for gender and English language proficiency and no interaction for gender and birthplace, although both interactions have been associated with Asian American smoking prevalence (Chae et al., 2006; Maxwell et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2005). One reason for this observation may be that most Asian American men smoke in a light and intermittent pattern, and there is no significant difference in the interaction by gender. Another possibility is that the power may be too low to detect a statistically significant difference, since there are few Asian American women smokers.

Slower nicotine metabolism and cotinine clearance may help explain why Asian Americans are disproportionately lighter smokers. Chinese American smokers have been shown to have a lower intake of nicotine per cigarette than Whites (Benowitz, Pérez-Stable, Herrera, & Jacob, 2002). Studies conducted in Asian countries found higher frequencies of genetic variations for slower nicotine metabolism in Asian compared with European and Middle Eastern populations, but variations also were demonstrated between Japanese and Koreans (Kim et al., 2007). Nicotine metabolism alone is insufficient to explain ethnic differences considering that White and Latino smokers had similar nicotine metabolism and intake of nicotine per cigarette (Benowitz et al., 2002) but more than 70% of Latino smokers in California smoke fewer than 5 cigarettes/day (Zhu, Pulvers, Zhuang, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2007). Furthermore, nicotine metabolism does not help explain gender differences, since nicotine metabolism ratios were not different between gender for Asian American young adult smokers, unlike Whites and Latinos (Kandel, Hu, Schaffran, Udry, & Benowitz, 2007).

The predominance of Asian American light and intermittent smoking patterns has important implications for developing effective tobacco control outreach. Although Korean and Vietnamese American men have high smoking prevalence rates (35.9% and 31.6%, respectively; Tang et al., 2005), our results demonstrate that the former are moderate/heavy smokers and the latter are light and intermittent smokers. Furthermore, addressing Asian American smokers’ psychosocial motivations for smoking may be more important than addiction. Psychological factors, such as depression, stress, and anxiety, have been associated with higher smoking rates in Korean, Vietnamese, and Filipino men in the United States (Kim et al., 2007; Maxwell, Garcia, & Berman, 2007). Vietnamese and Filipino men smokers also had higher rates of agreeing that “smoking is part of social interactions” (Chan et al., 2007; Maxwell et al., 2007).

Among the limitations of the present study, it represents Asian Americans in California only, where smoking prevalence is lower than in non-Western regions (Chae et al., 2006). Recent immigrants may not have as much access to a telephone or desire to participate in a survey asking personal information. The survey is cross-sectional and cannot determine stability of smoking patterns. The number of smokers among the different Asian national origin groups was particularly small for South Asians, Japanese, and other Asians, which reflects that the CHIS survey did not oversample these groups. The survey was not conducted in-language for all groups, which may have biased those samples toward more acculturated adults.

Further studies are needed to elaborate the relationships among biological, psychosocial, and cultural factors influencing smoking intensity between groups of different Asian national origin. Future outreach should consider behavioral cessation strategies, while considering whether moderate/heavy smoking populations such as Korean and Japanese men require a pharmacotherapy emphasis.

Funding

American Heart Association, National Institutes of Health Fogarty (TW05938); Asian American Network for Cancer Awareness, Research, and Training program through a National Cancer Institute Cooperative Agreement.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- Benowitz NL, Pérez-Stable EJ, Herrera B, Jacob P., 3rd. Slower metabolism and reduced intake of nicotine from cigarette smoking in Chinese-Americans. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94:108–115. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.2.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2003 methodology series: Report 4—Response rate. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of cigarette use among 14 racial/ethnic populations—United States, 1999–2001. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Gavin AR, Takeuchi DT. Smoking prevalence among Asian Americans: Findings from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) Public Health Reports. 2006;121:755–763. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan NL, Thompson B, Taylor VM, Yasui Y, Harris JR, Tu SP, et al. Smoking prevalence, knowledge, and attitudes among a population of Vietnamese American men. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(Suppl. 3):475–484. doi: 10.1080/14622200701587086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin E, White M, White V, Distefan J, Trinidad D, James L, et al. Tobacco control successes in California: A focus on young people, results from the California Tobacco Surveys, 1990–2002. La Jolla, CA: University of California, San Diego; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hassmiller KM, Warner KE, Mendez D, Levy DT, Romano E. Nondaily smokers: Who are they? American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1321–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Hu MC, Schaffran C, Udry JR, Benowitz NL. Urine nicotine metabolites and smoking behavior in a multiracial/multiethnic national sample of young adults. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;165:901–910. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SS, Ziedonis D, Chen KW. Tobacco use and dependence in Asian Americans: A review of the literature. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:169–184. doi: 10.1080/14622200601080323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AE, Bernaards CA, McCarthy WJ. Smoking prevalence and correlates among Chinese- and Filipino-American adults: Findings from the 2001 California Health Interview Survey. Preventive Medicine. 2005;41:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AE, Garcia GM, Berman BA. Understanding tobacco use among Filipino American men. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:769–776. doi: 10.1080/14622200701397890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi K, Harris K, Scheibmeir M, Choi W, Powell J, Ahluwalia J. Light smokers: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4(Suppl. 2):S103–S112. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000032726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Shimizu R, Chen MJ. English language proficiency and smoking prevalence among California's Asian Americans. Cancer. 2005;104(Suppl.):2982–2988. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco use among U.S. racial/ethnic minority groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wortley PM, Husten CG, Trosclair A, Chrismon J, Pederson LL. Nondaily smokers: A descriptive analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:755–759. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000158753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Pulvers K, Zhuang Y, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Most Latino smokers in California are low-frequency smokers. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl. 2):104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.