Abstract

Background

Hamstring strains are among the most frequent injuries in sports, especially in events requiring sprinting and running. Distal tears of the hamstring muscles requiring surgical treatment are scarcely reported in the literature.

Objective

To evaluate the results of surgical treatment for distal hamstring tears.

Design

A case series of 18 operatively treated distal hamstring muscle tears combined with a review of previously published cases in the English literature. Retrospective study; level of evidence 4.

Setting

Mehiläinen Sports Trauma Research Center, Mehiläinen Hospital and Sports Clinic, Turku, Finland.

Patients

Between 1992 and 2005, a total of 18 athletes with a distal hamstring tear were operated at our centre.

Main outcome measurements

At follow‐up, the patients were asked about possible symptoms (pain, weakness, stiffness) and their return to the pre‐injury level of sport.

Results

The final results were rated excellent in 13 cases, good in 1 case, fair in 3 cases and poor in 1 case. 14 of the 18 patients were able to return to their former level of sport after an average of 4 months (range 2–6 months).

Conclusions

Surgical treatment seems to be beneficial in distal hamstring tears in selected cases.

Hamstring injuries can occur in a variety of sports activities and they are among the most frequent injuries in sports, especially in events requiring sprinting and running.1,2,3,4,5 Most of these injuries are strains and are treated adequately by generally approved non‐operative methods.6,7

Only a few reports on the treatment of distal tears of the hamstring muscles have been previously published in the English literature.8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 We present our results of surgical treatment of distal hamstring tears in 18 athletes. We also reviewed the previously published cases with regard to the treatment of distal hamstring tears. The aim of this study was to provide more information about surgical treatment in athletes with a distal hamstring tear.

The study protocol was approved by the local hospital ethics committee of Satakunta Central Hospital, Pori, Finland.

Patients and methods

In total, 18 athletes (16 men and 2 women) with a distal hamstring tear were surgically treated at Mehiläinen Hospital and Sports Clinic, Turku, Finland, during 1992–2005. One athlete was operated on twice. There were 6 professional athletes (international elite level), 10 competitive‐level athletes and 2 recreational athletes. The mean age of the patients was 28 years (range 18–40 years). The right side was affected in 13 patients and the left side in 5 patients. Table 1 presents the details of each patient. All injuries occurred during sports, and typically in sprinting. There was no direct blow to the distal part of the posterior thigh in any of the patients.

Table 1 Background, surgical findings and results of treatment in 18 patients with a distal tear of the hamstring muscles.

| Age (years) | Sport | Delay from injury to surgery (months) | Involved muscle and location of tear | Complete (C) or partial (P) tear | Return to pre‐injury level of sport (months) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Ice hockey | 5 days | BF/A | C | 2 | Excellent |

| 27 | Floorball | 2 weeks | BF/MTJ | C | 3 | Excellent |

| 24 | Sprinting* | 1.5 | BF/MTJ | P | 5 | Excellent |

| 20 | Long jump | 3 | BF/MTJ | P | 3 | Excellent |

| 24 | Sprinting* | 3 | BF/MTJ | P | 4 | Excellent |

| 40 | Marathon* | 3 | BF/MTJ | P | 4 | Excellent |

| 24 | Soccer | 3 | BF/T | P | 5 | Excellent |

| 18 | Sprinting* | 4 | BF/MTJ | P | 2 | Excellent |

| 29 | Triathlon* | 5 | BF/MTJ | P | 5 | Good |

| 24F | Road cycling | 9 | BF/MTJ | P | 3 | Excellent |

| 18 | Sprinting* | 15 | BF/MTJ | P | 2 | Excellent |

| 34 | Soccer* | 1,5 | SM/MTJ | C | 6 | Excellent |

| 28 | Soccer | 6 | SM/MTJ | P | DNR | Fair |

| 21 | Orienteering | 12 | SM/MTJ | P | DNR | Fair |

| 37 | Golf | 12 | SM/MTJ | P | DNR | Fair§ |

| 38F | Dancing† | 72 | SM/MTJ | P | DNR | Poor§ |

| 24 | Soccer | 2 weeks | ST/A | C | 5 | Excellent |

| 25 | Baseball‡ | 1 | ST/MTJ | C | 5 | Excellent |

A, avulsion; BF, biceps femoris; C, complete rupture; DNR, did not return to previous level of sports activity; F, female; MTJ, myotendinous junction; P, partial rupture; SM, semimembranosus; ST, semitendinosus; T, tendinous part.

*The injury occurred while running fast/sprinting.

†This athlete was operated on twice.

‡Finnish baseball.

§Signs of severe denervation of contractile muscle (SM) fibres.

The diagnosis was based on the history, clinical examination and imaging findings. Commonly reported symptoms were weakness in knee flexion, as well as pain and stiffness of the distal part of the posterior thigh. A sense of instability of the knee joint was reported by five patients with a complete distal hamstring tear. Two patients reported muscle cramps and spasms of the posterior thigh. Weakness in knee flexion was found on clinical examination, as well as pain and tenderness of the distal thigh. In patients seen in the early phase, localised swelling and haematoma of the distal posterior thigh was noted. A proximally retracted muscle belly and a palpable defect were present in five patients with a complete rupture. The preoperative diagnosis was confirmed by either magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound.

The average time span from the injury to surgery was 8.5 months (range 5 days to 6 years; median 3 months). Four of the operations were performed within 1 month from the injury. At the time of surgery, the athletes were unable to participate in their sport at the pre‐injury level because of their symptoms.

In surgery, spinal anaesthesia was used. An incision was made over the injured area. The fascia of the hamstring compartment was opened and the injured structure was identified. In all 18 cases, a distal hamstring tear was found. The biceps femoris muscle was injured in 11 patients, the semimembranosus muscle in 5 patients and the semitendinosus muscle in 2 patients. Of the 18 cases, 15 were located at the myotendinous junction (MTJ), 2 were avulsions and 1 was a longitudinal tear of the tendinous part. Table 1 presents the details of these surgically treated muscle tears.

Of the 15 cases in which the tear was located at the MTJ, it was repaired in 13 cases using sutures after excision of scar tissue. Adhesions were released and the injured muscle was mobilised. The remaining 2 had muscle cramps and spasms, and a tenotomy was performed to the distal semimembranosus tendon. No suturing was performed in these two patients.

In the first of the two cases in which an avulsion was found, the avulsed biceps femoris tendon was reinserted to the head of the fibula with a suture anchor (Mitek, Norwood, Massachusetts, USA). Anatomical reinsertion without considerable tension was not possible in the second case, in which there was an avulsion of the semitendinosus tendon. In this case, the torn semitendinosus tendon was reinserted with sutures to the tendinous part of the sartorius muscle.

In the final case, a longitudinal tear was located at the tendinous part of the biceps femoris muscle. The tear was repaired with sutures after excision of scar tissue.

An elastic bandage was used for 3–5 days postoperatively. No immobilisation was used. The patients were allowed to begin partial weight‐bearing within 2 weeks. Full weight‐bearing was allowed within 4 weeks, and swimming and water training were allowed 2–4 weeks after surgery. Bicycling with gradually increasing time and intensity was begun after 3–6 weeks. Running was allowed 6–8 weeks after the operation.

The patients were followed postoperatively at our outpatient clinic. During the first 3–5 months there were monthly routine visits, and after that as necessary. Additional long‐term follow‐ups were scheduled for the study purposes. At the most recent follow‐up, the patients were asked about possible symptoms (pain, weakness, stiffness) and their return to the pre‐injury level of sport.

The result was classified as excellent if the patient was asymptomatic and able to return to the pre‐injury level of sporting activity. If there were occasional minimal symptoms in the affected leg during strenuous sports activity, but the patient was able to return to the pre‐injury level of sports, the result was classified as good. A classification of fair was assigned to the result when moderate training was possible, but the patient was unable to carry out strenuous exertion and was unable to return to the pre‐injury level of sports. Finally, the result was classified as poor when the patient had occasional disturbing symptoms even in activities of daily living.

Results

The mean length of the follow up was 37 months (range 12–78, median 30 months). In four cases, the follow‐up was <2 years. The results were rated excellent in 13 cases, good in 1 case, fair in 3 cases and poor in 1 case (table 1). In all, 14 of the 18 patients were able to return to their pre‐injury level of sports an average of 4 months (range 2–6 months) after surgery. All 18 patients benefited subjectively from the surgery.

The 13 athletes who were rated as having an excellent result were asymptomatic during their athletic performances after the surgical treatment, and full return to the pre‐injury level of sports was possible.

One professional triathloner was rated as having a good result. After surgery, he was able to return to his pre‐injury level of sports but had minor symptoms (weakness and stiffness) during strenuous sporting activities.

Three athletes (professional golfer, competitive level orienteerer and competitive level soccer player) with results rated as fair had to end their sporting careers despite surgical treatment. They were able to participate in recreational sports but unable to return to their pre‐injury level of sports.

One case in which the result was rated poor was a professional dancer, and she was operated on twice. The delay from the injury to the first operation was 6 years. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies carried out before the first operation showed signs of denervation of the semimembranosus muscle. The patient had tightness, painful cramps and spasms of the posterior thigh while trying to extend the knee. Botulinum toxin injections given before the referral had decreased the symptoms, but she was able to walk only with the help of crutches and an elastic support sleeve around her thigh before the surgery. At the first operation, a partial distal tenotomy of the semimembranosus tendon was performed. After the first operation, the patient still had disturbing symptoms in activities of daily living. A second operation was performed 1 year later. This time a proximal tenotomy of the semimembranosus muscle was performed just distal to the origin at the ischial tuberosity and also a new tenotomy at the distal MTJ of the semimebranosus muscle. Three months after the second operation, the patient was able to walk without crutches. The result was still rated as poor. However, subjectively, the patient was satisfied with the final outcome after having had painful muscle cramps and spasms for 6 years.

Postoperatively, in two patients, there was a small seroma formation, which was effectively treated with needle aspirations. One patient had minor hyperesthesia of the incision area and the anteromedial aspect of the knee postoperatively, but this symptom resolved during the follow‐up period of 5 years.

Discussion

A Medline search was performed to review the literature, and eight case reports were found.8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 Only cases from the English literature regarding the treatment of distal hamstring tears were included. To our knowledge, our study is the largest series of patients with a distal hamstring tear ever reported.

The biceps femoris muscle has been shown to be a strong flexor and an important dynamic stabiliser of the knee, and injury to its distal part may result in weakness and instability of the knee, especially in athletes.15,16,17 Therefore, it would seem reasonable to advocate restoration of normal anatomy to minimise loss of function and strength.

Six of the eight previously published case reports concerned a distal tear of the biceps femoris (a total of eight cases with seven athletes).9,10,11,12,13,15 In all eight cases, the tear was complete: either an avulsion or a complete tear at the distal MTJ. In six cases, the tear was treated operatively (five in the acute phase and one after failed conservative treatment that had lasted for 4 months), and in two cases non‐operatively. Five of the eight athletes were able to participate in their sports for a period varying from 3 weeks to 6 months after the injury. The results of operative versus non‐operative treatment are inconsistent, and the data on the return to sports and the follow‐up were poorly reported, so it was impossible to draw any conclusions between different treatment strategies.

In our study, there were 11 cases in which the distal biceps femoris muscle was injured. In nine cases, the tear was located at the MTJ. Eight of these nine tears were partial and were operated on 6 weeks to 15 months after the injury because of unsatisfactory results of non‐operative treatment. Two complete tears (one avulsion and one at the MTJ) were surgically treated within 2 weeks from the injury. In one case, a longitudinal tear of the biceps femoris tendon was surgically treated because of longlasting pain preventing sports activity. All these 11 athletes were able to return to their pre‐injury level of sports an average of 3.5 months (range 2–5 months) after surgery.

According to the previously published studies and the findings of our study, patients with a distal tear of the biceps femoris can be expected to return to their pre‐injury level of sports after surgery.

After a disruptive shearing type of injury, the affected area of skeletal muscle undergoes remodelling, with resultant scar formation.6 Excessive scarring and formation of adhesions, as was the case in the eight partial tears at the MTJ of the biceps femoris muscle in this study, can lead to impaired muscle function and reduced biomechanical properties.7 Äärimaa et al18 observed that close apposition by suturing of transected myofibres in rat soleus muscle restored myofibre continuity, and reduced the extent of the intervening scar tissue and accelerated healing. This healing mechanism may explain why in those partial tear cases in this study, the controlled suturing treatment after excision of excessive scar and adhesions seemed to be beneficial in treating partial muscle tears.

The semimembranosus muscle has an important function in knee flexion and in medial rotation of the tibia.19 To our knowledge, only one study, by Alioto et al8 has previously reported a case of distal semimembranosus muscle tear. After the injury, the 25‐year‐old professional soccer player was unable to return to sports because of severe pain, weakness and instability of the affected leg. In surgery that was performed soon after the injury, the avulsed semimembranosus tendon was reinserted with a suture anchor. The athlete could return to his pre‐injury level of professional sports 11 weeks after the surgery.

In our series, there were five athletes with a distal tear at the MTJ of the semimembranosus muscle: one complete and four partial tears. The patient with a complete tear was surgically treated 6 weeks after the injury, and he was able to return to his pre‐injury level of sports 6 months after surgery. In the patients with partial tear, surgery was performed 6–72 months after the injury. None of these four athletes were able to return to the pre‐injury level of sports even after surgical treatment. A muscle biopsy was performed in two of these four cases, and there were signs of severe denervation of muscle fibres.

It seems that in cases of a complete tear of the distal semimembranosus muscle, surgery in the early phase leads to good results. It also seems that if the partial tear occurs at the distal MTJ of the semimembranosus muscle, there is a risk of permanent muscle damage and therefore a poorer prognosis after surgical repair at least in late surgery. To our knowledge, there are no results of conservative treatment published.

The semitendinosus muscle has an important contribution in knee flexion strength at higher flexion angles and also an important function in medial rotation of the tibia.20,21 To our knowledge, only one study, by Schilders et al14 has been published on the treatment of distal semitendinosus muscle tears. The authors reported a series of four professional sportsmen with a partial rupture of the distal semitendinosus tendon successfully treated by tenotomy after failed conservative treatment. Before surgery, the patients had debilitating pain that had rendered them unable to participate in anything other than light training. All four patients returned to professional sports after surgery. The authors concluded that if a partial distal semitendinosus rupture is identified and conservative treatment fails, tenotomy should be considered.

What is already known on this topic

The hamstrings are one of the most frequently injured muscles in sports, especially in events requiring sprinting and running.

However, there is very little scientific evidence on the management of distal hamstring muscle injuries.

What this study adds

This study adds information of the surgical treatment of distal hamstring tears in athletes.

In contrast with the series by Schilders et al,14 in our study, both tears were complete: one avulsion and one at the distal MTJ. The delay from the injury to surgery was 2 weeks and 1 month, respectively. Both these athletes were able to return to their pre‐injury level of sports 5 months after surgery. To our knowledge, there are no previously published studies relating to the surgical treatment of complete tears of the distal semitendinosus muscle.

One might question the necessity of surgical treatment in cases of distal semitendinosus tears. After all, it is a tendon commonly used as a graft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. However, studies show that harvesting of the semitendinosus tendon leads to a loss of knee flexor strength and impaired dynamic stability.20,21,22 Furthermore, even though it has been shown that the medial hamstring tendons regenerate in most patients after their harvest for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, the regenerated neotendon may have impaired biomechanical properties compared with the original semitendinosus tendon.23 In addition, to our knowledge, no one has shown that regeneration of the semitendinosus occurs after a traumatic rupture.

The decision of surgical treatment in the two cases in our study was made because both athletes had severe pain, sense of instability and weakness of the knee after the injury. It may be worth trying to restore the function of a traumatically torn semitendinosus muscle especially in athletes, who compete in sports activities demanding deep flexion and rotational strength of the knee, such as soccer and baseball.

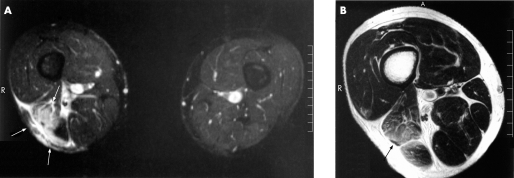

Previously published reports of distal hamstring tears are scarce. This is probably because these tears are unusual and also they may be underdiagnosed. From our experience, the severity of the distal hamstring injury is often difficult to assess by clinical examination only. Diagnostic imaging is a valuable option and helps in decision making. MRI has good soft tissue resolution, and it enables imaging in multiple planes. Excellent image information should be used when selecting treatment options. Figure 1 shows an example of MRI findings of the partial distal biceps femoris tear.

Figure 1 (A, B) Magnetic resonance images of an athlete with an acute right distal hamstring tear. (A) Axial image (proton density (PD) fast spin echo (FSE) with fat suppression TR/TE 5000/90 ms) with a partial biceps femoris tear at the distal myotendinous junction. The site of the injury is easily seen owing to the sensitivity of the sequence for soft tissue oedema and haematoma at the injury site (white arrows). Distal hamstring muscles of the left thigh are intact. (B) Despite the massive oedema, the preservation of the muscle structure is better visualised on the T2‐weighted FSE images (PD TR/TE 3500/83 ms). The distal biceps femoris tendon is indicated by a black arrow.

In this study, none of the 18 athletes with a distal hamstring tear were able to participate in their pre‐injury level of sports owing to their symptoms before the surgery. In total, 14 athletes were able to return to the pre‐injury level of sports after surgery.

In conclusion, our results suggest that surgical treatment seems to be beneficial in selected cases of distal hamstring tears, and in most of these cases, excellent or good results can be expected. However, only prospective, randomised studies would reliably prove the efficacy of surgical treatment compared with non‐surgical treatment.

Acknowledgements

Lasse Lempainen is a PhD student of the Graduate School of Musculoskeletal Diseases and Biomaterial (TULES) in Finland.

Abbreviations

MRI - magnetic resonance imaging

MTJ - myotendinous junction

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported financially by the Satakunta Central Hospital District (EVO), the Finnish Cultural Foundation and the Finnish Sports Research Foundation.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Agre J C. Hamstring injuries. Proposed aetiological factors, prevention, and treatment. Sports Med 1985221–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brubaker C E, James S L. Injuries to runners. J Sports Med 19742189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clanton T O, Coupe K J. Hamstring strains in athletes: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 19986237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lysholm J, Wiklander J. Injuries in runners. Am J Sports Med 198715168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volpi P, Melegati G, Tornese D.et al Muscle strains in soccer: a five‐year survey of an Italian major league team. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 200412482–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Järvinen T A H, Järvinen T L N, Kääriäinen M.et al Muscle injuries: biology and treatment. Am J Sports Med 200533745–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kujala U M, Orava S, Järvinen M. Hamstring injuries. Current trends in treatment and prevention. Sports Med 199723397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alioto R J, Browne J E, Barnthouse C D.et al Complete rupture of the distal semimembranosus complex in a professional athlete. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997336162–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.David A, Buchholz J, Muhr G. Tear of the biceps femoris tendon. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1994113351–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortems Y, Victor J, Dauwe D.et al Isolated complete rupture of biceps femoris tendon. Injury 199526275–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen I H, Kramhoft M. Distal rupture of the biceps femoris muscle. Scand J Med Sci Sports 19944259–260. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGoldrick F, Colville J. Spontaneous rupture of the biceps femoris. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1990109234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan K L, Ting F. Delayed repair of rupture of the biceps femoris tendon – a case report. Med J Malaysia 200055368–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schilders E, Bismil Q, Sidhom S.et al Partial rupture of the distal semitendinosus tendon treated by tenotomy – a previously undescribed entity. Knee 20061345–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sebastianelli W J, Hanks G A, Kalenak A. Isolated avulsion of the biceps femoris insertion. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990259200–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall J L, Girgis F G, Zelko R R. The biceps femoris tendon and its functional significance. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1972541444–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tubbs R S, Caycedo F J, Oakes W J.et al Descriptive anatomy of the insertion of the biceps femoris muscle. Clin Anat 200619517–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Äärimaa V, Kääriäinen M, Vaittinen S.et al Restoration of myofiber continuity after transection injury in the rat soleus. Neuromuscul Disord 200414421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cross M J. Proceedings: the functional significance of the distal attachment of the semimembranosus muscle in man. J Anat 1974118401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segawa H, Omori G, Koga Y.et al Rotational muscle strength of the limb after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using semitendinosus and gracilis tendon. Arthroscopy 200218177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tashiro T, Kurosawa H, Kawakami A.et al Influence of medial hamstring tendon harvest on knee flexor strength after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A detailed evaluation with comparison of single‐ and double‐tendon harvest. Am J Sports Med 200331522–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura N, Horibe S, Sasaki S.et al Evaluation of active knee flexion and hamstring strength after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using hamstring tendons. Arthroscopy 200218598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carofino B, Fulkerson J. Medial hamstring tendon regeneration following harvest for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: fact, myth, and clinical implication. Arthroscopy 2005211257–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]